Gardiner V., Matthews H. The changing geography of the United Kingdom

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

DAVID SADLER

136

changes included an increased share of output derived from manufacturing in the North and

in Northern Ireland (both up by two percentage points, against the national trend) and an

above-average decline (around three percentage points) in the South East, South West, North

West and Merseyside, and Scotland.

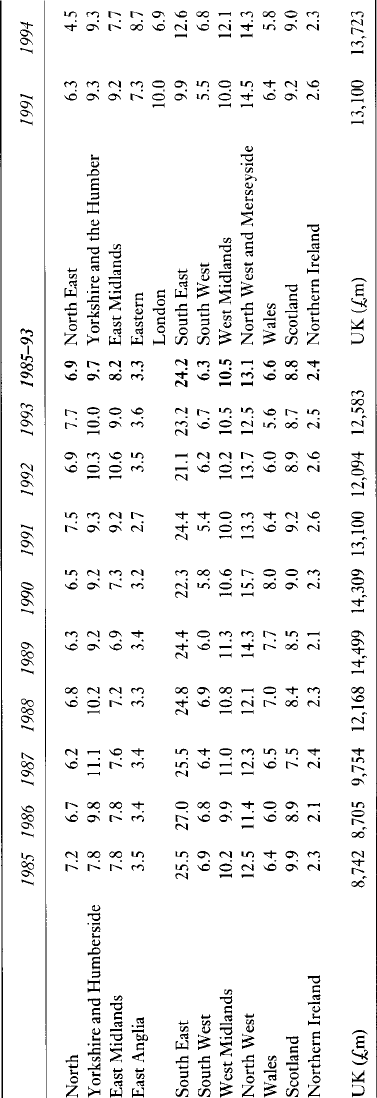

Net capital expenditure in manufacturing—expressed as a percentage of the UK total—

is intrinsically more variable from year to year than output and employment, so that it is

presented here in the form of an average over the period from 1985 to 1993 (Table 7.5).

This shows that despite the South East’s relatively low dependence upon manufacturing

industry, so great is the weight of this region within the UK economy that it accounted for

almost a quarter of all investment in manufacturing, well above its nearest rivals the North

West and Merseyside (13 per cent), the West Midlands (11 per cent) and Yorkshire and the

Humber (10 percent).

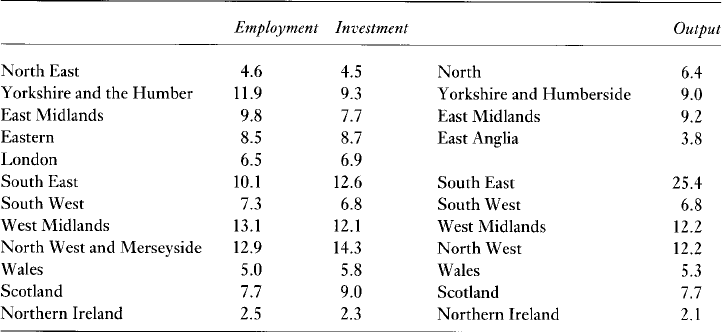

On this basis too—expressed as a proportion of the UK total rather than of

individual regional totals—the distributions of manufacturing employment and

manufacturing output also largely reflect the differing weights of each regional economy

(Table 7.6). The South East accounted for a quarter of manufacturing output in 1995,

well above the West Midlands and the North West with 12 per cent each, whilst the

small size of the manufacturing base in Northern Ireland and East Anglia was particularly

evident, with these regions accounting for just 2 and 4 per cent of the UK total

respectively. The North had a slightly higher share of output than of employment (even

after allowing for some discrepancy introduced by differing regional bases for data

collection), whilst Yorkshire and Humberside and the West Midlands had a higher share

of employment than of output.

These, then, were the broad regional dimensions of UK manufacturing employment,

output and investment in the period since the mid-1980s; years which saw continued

relative decline in the sector, particularly in the early 1990s. That recession sharpened

earlier concerns about the state of manufacturing in the UK and led to a full-scale

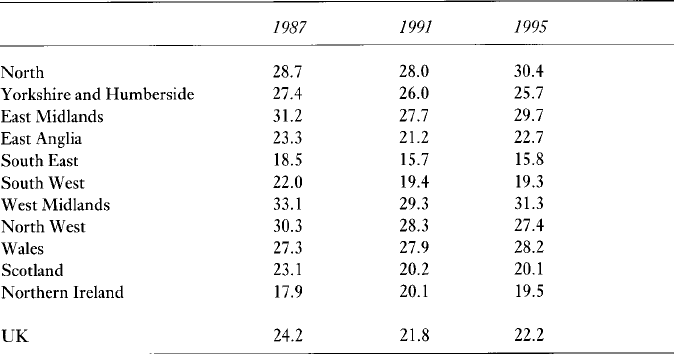

TABLE 7.4 Manufacturing as a percentage of regional Gross Domestic Product, 1987, 1991

and 1995

Sources: Calculated from Regional Trends 27, Table 12.2; Regional Trends 32, Table 12.4.

Note: 1980 SIC for 1987; 1992 SIC for 1991 and 1995.

TABLE 7.5 Net capital expenditure in manufacturing by region as a percentage of UK total, 1985–94

Source: Regional Trends, various dates.

Note: 1980 SIC (SSRs, 1985–92); 1992 SIC (SSRs, 1993 and GORs, 1991 and 1994).

DAVID SADLER

138

investigation by a House of Commons Select Committee into the competitiveness of UK

manufacturing (Trade and Industry Committee 1994). This report argued strongly that

the declining relative significance of manufacturing to the UK economy—which had

been more severe than in practically all other developed economies—should be a cause

for concern. This was so not least because the sector accounted for over 60 per cent of UK

exports (making the country the world’s fifth largest exporter of manufactured goods),

and a significant proportion of the service industries depended to some extent on

manufacturing. The prospect of renewed extensive growth in employment in manufacturing

was, however, discounted:

Given the continuing rise in productivity, the jobs lost in manufacturing in developed

countries in recent years are unlikely ever to be fully restored, even if output rises.

Consequently we believe that growth in the UK’s manufacturing sector should be

viewed primarily as a way of increasing the creation of national wealth and thus of

jobs elsewhere in the economy rather than of creating jobs in manufacturing itself.

(Trade and Industry Committee 1994:15; emphasis added)

The report went on to stress that there were, none the less, prospects for renewed growth

in output, partly resulting from a short-term advantage of low labour costs but in the

longer-term dependent upon continued good industrial relations, new management

practices, and the UK’s attractiveness as a location for foreign direct investment in

manufacturing (themes which are expanded upon in the following sections). In addition,

it highlighted two areas in which the UK possessed specific weaknesses that needed to be

addressed: the size distribution of manufacturing firms, and the nature of the links between

manufacturing and finance capital.

TABLE 7.6 Employment, output and investment in manufacturing by region as a percentage of

UK total, 1995

Source: Regional Trends 32, Tables 5.8, 12.4 and 13.4.

Note: 1992 SIC. Investment data for 1994.

MANUFACTURING INDUSTRY

139

Whilst the UK was seen as being particularly strong in large international

manufacturing companies—with forty-three of the world’s 500 largest such firms in terms

of turnover based there, against thirty-three in Germany and thirty-two in France—it was

described as ‘exceptionally weak’ (p. 28) in medium-sized firms (those employing from

100 to 500 people), comparable to Germany’s Miitelstand. Such firms accounted for just 16

per cent of manufacturing employment in the UK in 1990, against 28 per cent elsewhere in

Western Europe. The UK also had an under-representation of smaller-sized enterprises,

with firms of from 20–100 employees accounting for just 15 per cent of manufacturing

employment against 23 per cent in the rest of Western Europe.

The UK’s pattern of ownership of larger firms was also addressed. Pension funds

alone held 35 per cent of the value of the shares in UK quoted companies in 1992;

together with insurance companies, that proportion increased to 60 per cent. This

was in contrast to the USA, where private shareholdings were more significant, and

to Germany, where banks were more influential. In both Germany and Japan, large

firms tended to have a small number of dominant shareholders, whilst in the USA and

the UK, individual shareholdings were much smaller. Thus in the UK, large

manufacturing firm ownership structures were distinctively characterised (amongst

large industrial economies) by a large number of small holdings in the hands of pension

funds and insurance companies, which collectively accounted for a significant part

of the total value of these manufacturing companies. This, it was argued, had led to a

degree of ‘short-termism’ (the favouring of short-term profits which could be

distributed in the form of dividends to shareholders) at the expense of longer-run

strategies. This had come about not necessarily because of the role of the financial

institutions, but due to the nature of the relationship between them and the

manufacturing sector.

Such concerns—about the degree of under-investment in UK manufacturing, and the

competitive position of UK-based small- and medium-sized manufacturing firms—were

increasingly regarded as significant policy issues in the course of the 1990s. This was in

contrast to the previous decade when government policy had seemed to prioritise the service

industries, particularly financial services. At the same time it was very clear that the prospects

of manufacturing in the UK now depended heavily upon the UK’s continued attractiveness

as a location for inward investment. The following section goes on to explore the debate

over the broader impact of such inward investment.

The extent and role of foreign direct investment in manufacturing

This section has two objectives: to describe some of the main regional impacts of flows of

FDI in manufacturing within the UK, and to consider the debate surrounding such inward

investment flows. The UK has been remarkably successful in attracting FDI. Over the period

since 1951 it has received two-fifths of all Japanese and one-third of all US inward investment

to the European Union. The absolute significance of FDI to the UK’s manufacturing sector

is widely attested. By the mid-1990s, foreign-owned manufacturing firms accounted for 25

per cent of the output of manufacturing industry in the UK and 20 per cent of manufacturing

employment, whilst 30 per cent of the country’s manufacturing exports consisted of trade

within international firms. Investment from overseas has led to dramatic changes in the

structure of many sectors, notably the automotive industry (Box 7.1).

DAVID SADLER

140

BOX 7.1 Case-study: the automotive industry

The fortunes of the automotive industry in the UK epitomise many of the changes

that have taken place within manufacturing since the depths of the early 1980s.

Production of passenger cars collapsed from 1.9 million in 1972 to a low of 0.9 million

in 1982, and hundreds of thousands of jobs were shed, notably in the West Midlands.

Thereafter, output began a recovery, reaching 1.7 million in 1997, with growth forecast

to continue to around 2 million by the early 2000s (although—in common with the

rest of the manufacturing sector—employment continued a steady decline). In part

this expansion came about because the UK was selected by three of the leading Japanese

automotive firms for their major inward investment sites in Europe. Nissan began

producing cars at Sunderland from 1986 onwards, whilst Toyota and Honda

commenced production at Burnaston in Derbyshire and Swindon respectively in 1992.

By the mid-1990s these firms had developed substantial manufacturing operations

(Nissan had invested over £1.5 billion, for example) and they were manufacturing 0.5

million cars a year between them. The vast majority of these were exported, contributing

substantially to the UK’s trade balance in manufactured goods. Nissan and Honda

had both announced plans to add a third model range, whilst Toyota had chosen instead

to develop an additional plant for its third model to be produced in Europe (at Lens in

northern France). Additionally, Rover—bought by BMW in 1994 from its previous

owner British Aerospace—was in the midst of a £3 billion investment programme to

the year 2000, whilst both Ford and General Motors (Vauxhall) had committed fresh

investment for the production of new models in the UK.

The significance of the investment from Japan in this sector went well beyond

the jobs created directly (amounting to no more than 12,000). All three firms sought

rapidly to reach a minimum of 80 per cent local content (meaning sourced from

within Europe) in the cars produced in their new factories, so that they could be sold

as European-produced rather than Japanese vehicles (thereby circumventing quotas

on imports from Japan). This brought Nissan, Toyota and Honda into close contact

with existing UK component suppliers. Considerable improvements in the performance

of these firms was both demanded and actively encouraged. Whilst they remained

behind the standards of Japanese suppliers in Japan, firms in the UK in particular

(and in Europe more generally) did succeed in closing the gap and securing a continued

stream of business. This not only ensured that jobs were created elsewhere in the

economy, it also further enhanced the UK’s attractiveness as a location for investment

in the automotive sector.

The proportion of value-added accounted for through FDI was at its highest in

Scotland and Northern Ireland (both at 35 per cent), Wales, the North East, and the South

East (all at 30 per cent), and at its lowest in the South West and East Midlands (16 per

cent) and Yorkshire and the Humber (17 per cent). The jobs created through inward

investment have also been unevenly distributed. From 1982 to 1992 over 50 per cent of

the jobs arising from FDI were located in Scotland, Wales and the North, compared to

only 16 per cent in southern England, whereas the respective shares of manufacturing

MANUFACTURING INDUSTRY

141

employment in 1992 were 18 per cent and 35 per cent (Trade and Industry Committee

1995: para 43). This is partly in response to the range of incentives available in these

areas from central government (an issue which is considered in a subsequent section).

Thus inward investment in manufacturing has not only underpinned the very existence of

the sector in the UK, but also contributed in some measure to a dampening of the regional

inequalities described in the previous section.

3

Some of the wider impacts of FDI—in particular the extent to which different

waves of investment have succeeded one another over time—can be illustrated with

respect to the case of the North of England (see Stone 1995). In 1978 there were 49,000

jobs in foreign-owned manufacturing establishments in the North, representing 12 per

cent of all employment in manufacturing in the region at that date. By 1993 there were

56,000 such jobs: at first sight, only a small absolute increase, even if collapse of UK-

owned firms meant that foreign-owned firms now accounted for 23 per cent of all

manufacturing employment there (a position comparable to Scotland, but below the 33

per cent recorded in Wales). This slight net gain however represented the sum total of

two very different processes: disinvestment by an earlier wave of American-owned firms

(leading to a net loss of 16,000 jobs) and investment by firms from Japan (leading to

9,000 new jobs, mainly at new greenfield plants) and from the rest of Europe (a net

gain of 13,000 jobs, mainly due to the acquisition of existing businesses). Thus it was

very evident that jobs created through FDI were by no means a permanent feature on

the economic landscape.

More generally, debate on the broader significance of FDI for regional and national

growth prospects intensified in the UK during the 1990s. The House of Commons Select

Committee enquiry into the competitiveness of manufacturing industry was quietly cautious

in its appraisal:

Inward investment offers considerable opportunities to the UK, but is unlikely to

involve the most up-to-date technology (other than production technology) and is

insufficient in scale to offset weaknesses in UK-owned manufacturing. It should

therefore be seen as a contribution towards a competitive UK manufacturing sector

but not as an alternative to improving the competitiveness of the sector as a whole.

(Trade and Industry Committee 1994:32)

Such caution reflected several aspects of emergent concern, including the extent to which at

least some inward investors had transferred only the simplest of production processes to the

UK. Some critics argued that the country’s key attraction lay purely in low labour costs and

that the production facilities being established there represented little more than a final

assembly point (sometimes described as a ‘screwdriver plant’ in recognition of the limited

extent of value-added locally) or a warehouse for components which were still largely

manufactured abroad. It was also argued that branch plants established in the peripheral

regions such as South Wales and north-east England were merely reproducing earlier rounds

of dependency, particularly in the extent to which these plants possessed only very limited

R&D capabilities.

Partly in response to these concerns, attention increasingly focused on a search for

‘quality’ or ‘performance’ plants. These were held to be sites at which inward investors had

developed high levels of local procurement, sophisticated recruitment and training practices,

DAVID SADLER

142

and a good level of integration or ‘embeddedness’ with local public and private development

organisations. Such ideas were expressed in a subsequent report from the Trade and Industry

Committee (1995: para 45). This recommended that getting the best from inward investment

involved developing a UK supply chain, ensuring that UK-owned firms learned from the

new working practices being adopted, targeting those firms likely to be of greatest benefit

to the UK (although in practice this was somewhat idealistic), and ensuring that reinvestment

by existing foreign-owned firms came to the UK.

New management styles and working practices

Many reasons have been advanced to account for the extent to which inward investors,

particularly those from Japan, favoured the UK as a base for inward investment in

Europe during the 1980s and 1990s. Of these, one of the most significant factors was

the extent to which the country welcomed the introduction of new working practices

and management styles such as Just-in-Time production, quality circles and the use of

team-working. In part, this openness to change rested on and helped to reinforce a

government policy to reduce the power of trade unions, one that was never more clearly

expressed than in the course of the 1984/5 strike in the coal-mining industry. One measure

of the extent of the changes that took place with respect to the broad climate of industrial

relations was that by the mid-1990s governments could point to good management-

employee relations as underpinning the prospects of the manufacturing sector, in stark

contrast to the problems which had been diagnosed just a decade previously. This is not

to suggest that all the changes which took place in terms of production organisation

and industrial relations during this period were due to the wave of FDI from Japan; but

there is no doubt that this inward investment (and its success) had a very important

demonstration effect.

The new industrial relations framework was described by the Trade and Industry

Committee (1994) as one of ‘empowerment’, built on dialogue and trust. The report went

on to argue that:

‘Empowerment’ does not remove the role of trade unions…Nonetheless the role of

trade unions is changing significantly as direct communication between management

and employees increases…We endorse the view that successful manufacturing

companies are likely to be those which have constructive relationships both with their

workforces and with the trade unions representing them, and that trade unions can

contribute to the successful implementation of change within companies.

(Trade and Industry Committee 1994:89)

This rosy picture of a harmonious alliance between capital and labour had its detractors,

some of whom argued that in essence not much had changed: that the ‘new’ management

style rested on little more than high unemployment and the enforced disciplining of wage

labour which that entailed.

These processes of change within the workplace were deeply significant. One

frequently cited example was the agreement between Nissan Motor Manufacturing (UK)

Ltd and the Amalgamated Engineering Union (AEU) made in 1985. This incorporated several

features which were new (as a package) to the automotive industry in the UK, including

MANUFACTURING INDUSTRY

143

single-union recognition, a company council elected from all employees, pendulum

arbitration, complete task flexibility, and common conditions. Not all FDI projects recognised

trade unions—in the electronics industry in particular, non-union plants were commonplace—

but those that did ensured that the union’s role was tightly delimited and that other channels

of management—employee communication were put in place. In this respect—as in other

fields, such as component purchasing and JIT buyer-supplier arrangements—the new plants

arising from inward investment looked less like transplants and more like hybrids, adopting

variants of best practice from the source country along with experience from other European

countries (especially Germany), all tailored to the UK setting.

The broader context for this process of transformation was an increasingly globalised

economy, and there was a lively debate in this period over the appropriate characterisation

of the changes that were taking place. Some argued there had been a transition from an

era of Fordist mass production to one of post-Fordism; others stressed the continued

vitality and adaptability of mass production. Some emphasised a shift towards a world of

flexible specialisation in which big firms no longer dominated and economies of scope

had replaced economies of scale; others re-affirmed the significance of mass markets. It

is, however, well beyond the scope of this present chapter to review these debates in

detail. Instead the following section considers the evolution of state policies towards

manufacturing in the UK.

The evolution of state policies towards the manufacturing sector

This section aims to explore two significant aspects in the evolution of UK government

policies towards the manufacturing sector. These are the pattern of expenditure of national

and European regional policies, and the intensification of regional rivalries in the pursuit

of FDI. Whilst all forms of public expenditure (and other government policies including

privatisation) have potentially uneven geographical implications, regional policies are of

particular significance in that they are expressly targeted at geographical outcomes and

have tended to focus upon manufacturing rather than service sector firms. There have

been major changes in the longer term to the system of regional policy in the UK. These

include the abolition of location controls through Industrial Development Certificates in

1982, after they had fallen into disuse in the 1970s, and the introduction of Regional

Selective Assistance (RSA) in 1972 to supplement automatic grants on investment in the

form of Regional Development Grant payments (RDG). Automatic grants were abolished

in 1988 leaving RSA as the main instrument of regional industrial policy. There have also

been many changes over time in the map of areas where firms are potentially eligible to

receive regional policy assistance, notably those in 1979, 1984 and 1988 which drastically

curtailed the extent of the Assisted Areas, although a subsequent revision in 1993 added

several districts in southern England which had been particularly badly affected by the

early 1990s recession.

Regional policy expenditure was cut back in the 1980s, along with many other

components of public expenditure, and preferential assistance was increasingly targeted

instead on urban measures. In 1993 this culminated in the creation of the Single

Regeneration Budget (SRB), which was led by the Department of the Environment and

brought together twenty separate programmes formerly administered by five different

government Departments, including the Urban Programme and the Urban Development

DAVID SADLER

144

Corporations (see Chapter 10). Its total funding of £1.6 billion in 1993/4 dwarfed

expenditure on regional preferential assistance in that year of £0.3 billion, and the transfer

to the SRB of responsibility for Regional Enterprise Grants and English Estates

(subsequently absorbed within English Partnerships) represented a significant reduction

of the Department for Trade and Industry’s regional policy role. The subsequent creation

of Government Offices for the Regions in 1994 brought together what were then the

Departments of Employment, Environment, Trade and Industry, and Transport. The Offices

for the Regions were given a remit of carrying out the regional activities of these

Departments, which included the administration of RSA and the newly created SRB.

These changes took place at a time when there was mounting concern over the effectiveness

of regional policy expenditure, leading to a review by the Trade and Industry Committee

(1995). This report concluded that there was still a strong case for the continuation of

regional policy,

4

particularly in order to improve the competitiveness of individual regional

economies, although there were several ways in which its delivery could be improved.

Not least among these was a need for more regional co-ordination, an issue considered in

more detail later in this section.

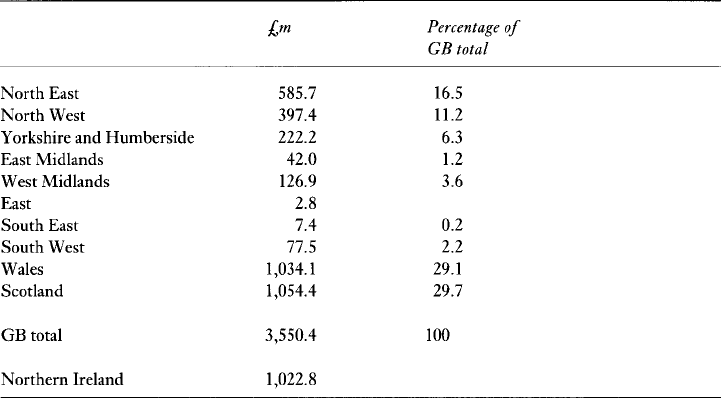

Despite continued contraction since the mid-1980s, government expenditure on regional

preferential assistance in Britain from 1988 to 1996 still amounted to £3.6 billion, with an

additional £1 billion spent under a different system in Northern Ireland (Table 7.7). This

expenditure was very heavily concentrated in a small number of regions. Wales and Scotland

both received just over £1 billion, or almost 30 per cent of the total each, followed by £600

million in the North East (17 per cent) and £400 million in the North West (11 per cent).

Expenditure from the EU’s Structural Funds within the UK had by contrast grown markedly

since 1989, with £3.4 billion at 1995 prices allocated in the programming period from 1989 to

1993 (Trade and Industry Committee 1995: para 18). A further £9 billion was committed

TABLE 7.7 Government expenditure on preferential assistance to industry by DTI region, 1988–96

Source: Calculated from Regional Trends 32, Table 13.7.

Note: Different system of assistance in Northern Ireland.

MANUFACTURING INDUSTRY

145

from 1994 to 1999, including (under Objective I) £830 million for Northern Ireland, £550

million for Merseyside and £210 million for the Highlands and Islands of Scotland. Main

recipients under Objective II included the West Midlands (£650 million), Manchester,

Lancashire and Cheshire (£580 million), Yorkshire and Humberside (£540 million), the North

East (£530 million), West Scotland (£470 million) and South Wales (£320 million).

EU Structural Funds differed from national regional policy in that the latter was

targeted at individual firms, whilst the former was delivered through a series of area-

based or thematic regeneration programmes. Much of the expenditure on national regional

policy thus represented a subsidy to inward investors, one which was offered as part of

the bidding process for FDI between competing potential locations. In the mid-1990s, a

succession of major success stories saw the UK seemingly re-confirm its position as

Europe’s prime inward investment location (Box 7.2). At the same time, however, the

increasingly intense competition between locations within the UK led to concern that a

degree of ‘bidding-up’ might be taking place, in which one UK location sought to outbid

another for the investment and jobs on offer, resulting in excessive public funds being

disbursed. The whole process by which inward investment enquiries were processed and

co-ordinated was explored in a report from the Trade and Industry Committee (1997).

This concluded somewhat equivocally that in a relatively small number of cases—mainly

larger projects—the extent of public assistance on offer could play a crucial, even

determining role in a company’s choice of location, but that there was ‘little substantial

evidence’ that bidding-up was taking place between locations in the UK. Equally, it found

claims that Welsh and Scottish agencies were attempting to ‘poach’ existing firms by

encouraging them to relocate there from sites in England to be ‘not very persuasive’.

This issue of co-ordination was of particular significance in the context of the newly

elected Labour government’s commitments to devolution in Scotland and Wales, and to the

creation of a network of Regional Development Agencies in nine of the English regions by

1999 (the exception was Merseyside, which was to be subsumed within the North West). The

Treasury wished inward investment to be controlled by one central body, the Department of

Trade and Industry’s Invest in Britain Bureau, but the Welsh and Scottish Offices had already

successfully resisted such a move in the last days of the Conservative government. The role of

the English RDAs was also the subject of political debate within the Labour government, with

the new Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions keen to take over co-

ordination through its control of the RDAs. In the event, however, the Department of Trade

and Industry secured continued control in the coordination of assistance to FDI within England,

although assistance to inward investors would be delivered through the network of RDAs.

Conclusion

This chapter first explored the performance of manufacturing industry since the mid-

1980s, concentrating on its regional implications. It went on to examine the extent and

role of foreign direct investment, identifying its uneven geographical impacts. The

introduction of new management styles and working practices within manufacturing

was also chronicled, in the context of changing trade union roles and management-

employee relationships. This was followed by a consideration of two aspects of state

policy towards manufacturing: regional policy, and the recent intensification of inter-

regional competition in the pursuit of inward investment.