Gardiner V., Matthews H. The changing geography of the United Kingdom

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

BRIAN TURTON

126

and social effects of a road scheme, including land-take, visual intrusion, impacts upon

urban and agricultural land uses, and heritage and ecological impacts, and then incorporates

the results within the cost-benefit analysis which is made during the consultation stages of

the scheme.

The spirited attempts to delay construction of the A34 Newbury bypass in Berkshire

by environmental groups illustrate the diversity of opinions on the benefits that the new

road is designed to yield when opened. Over 50,000 vehicles per day passed through

Newbury, which is on the trunk Euroroute EO5 for traffic between the Midlands and the

Channel ports. The £101 million bypass now diverts this traffic to the west of the town,

producing estimated savings of 15 minutes for long-distance vehicles passing through the

town at peak periods but savings of only 2 minutes at other times. Opposition to the bypass

was based upon its damaging effects upon the Kennet valley and neighbouring sites of

ecological and historical value, which were seen as outweighing the benefits that the road

would confer on traffic, whereas much of the support came from residents and businesses

within Newbury itself.

Securing an improvement in the quality of life by reducing the volume of

motorised traffic in our society is now acknowledged to be a key environmental

objective, and this aim is best achieved by reducing the level of vehicle emissions,

pursuing existing plans to reduce traffic flows in town centres and providing, wherever

possible, the necessary protection for areas of landscape value threatened by new

transport projects.

Although the 1992 European Union transport policy document (EC Commission 1992)

sees environmental issues as crucial to transport and mobility, the current situation is one of

contrast in terms of efforts made by individual member states. The Netherlands and Denmark,

together with certain cities in Germany and Switzerland, have devised realistic and effective

means of reconciling transport with the environment, but other states have yet to implement

such policies and the United Kingdom’s record to date in this area cannot be regarded as

wholly satisfactory.

Conclusions

The closing years of the twentieth century have seen several initiatives in the transport

sector designed to increase the overall efficiency of the system, to achieve a greater use of

public transport in towns and cities and to reduce the growing conflict between transport

and the environment. Many of the policies of the 1990s were inherited from the previous

decade, notably the deregulation and privatisation of bus undertakings, the progressive

reduction in state subsidies for rail and bus operations, and the investment in light rail

transit schemes for large cities. The most significant advance in the process of privatisation

in the 1990s was the completion of the franchising programme for rail passenger and freight

operators and the transfer of the railway and its supporting services to the private sector. In

terms of infrastructure the most significant events were the opening of the Channel Tunnel

and the completion of the major framework of the national motorway system, but a large

part of the major road investment programme announced in the late 1980s was halted in

early 1994 pending a review of the overall effectiveness of road building.

A major new direction in policy has been the encouragement of private

investment in new road projects, although to date progress has been limited to the

TRANSPORT

127

Birmingham Relief Road, now under construction. The White Paper of summer 1998

advocates a new transport policy based upon principles of integration and sustainable

development. The last comparable document dates back to June 1977, when the

declared objectives were to develop transport facilities to promote economic growth,

to meet social needs and to take account of environmental protection (Department of

Transport 1977). These aims have been met with varying degrees of success in the

past two decades, but the new White Paper sets out a more positive approach to the

transport industry. A prime objective is to consider all new transport investments in

the context of sustainable development and to ensure the effective integration of the

different modes. The existing situation of competition between and within modes is

unlikely to receive much support in the future and a recurrent theme in recent

government statements is the need to give public transport a much higher priority and

to strengthen existing strategies designed to discourage the use of cars for trips that

could be carried out by bus or rail. One of the most challenging areas for action is the

management of demand for road space in terms of both future road-building policy

and plans to restrain private motoring through increased taxes on fuel or higher vehicle

licensing costs.

The wider issue of promoting regional development, especially in areas of economic

decline, through the medium of improved transport facilites will also need to be addressed.

The contributions that new motorways or electrified railways can make to industrial revival

are not as significant as was once thought, and the effects of the Channel Tunnel, in terms of

favouring the South East’s economy at the expense of already declining regions in the

periphery of Britain, are still being evaluated. Making use of the Tunnel to promote closer

integration with European transport systems will depend upon to the extent to which the

road and railway systems within Britain can be improved to meet the demands of domestic

and international traffic.

References

Banister, D. (1996) ‘Energy, quality of life and the environment: the role of transport’, Transport

Reviews 16(1): 23–35.

Bassett, K. (1993) ‘British port privatization and its effect upon the port of Bristol’, Journal of Transport

Geography 4(1): 255–67.

Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions (1998) A New Deal for Transport: Better

for Everyone, London: HMSO.

Department of Transport (1963, 1965) The Re-shaping of British Railways, Parts I and II (Beeching

Report), London: HMSO.

Department of Transport (1977) Transport Policy, London: HMSO.

Department of Transport (1989) Roads for Prosperity, London: HMSO.

Department of Transport (1993) Paying for Better Roads, London: HMSO.

Eaton, B.D. (1997) ‘Passenger services under the Railways Act’, Proceedings Chartered Institute of

Transport 6(1): 14–28.

EC Commission (1992) The Future Development of the Common Transport Policy, Com 92 454,

Brussels.

Farington, J. and Ryder, A. (1993) ‘Environmental assessment of transport infrastructure’, Journal of

Transport Geography 2(1): 102–18.

Knowles, R.D. (1996) ‘Transport impacts of Greater Manchester’s Metrolink system’, Journal of

Transport Geography 4(1): 1–14.

Harnden, M. (1997) ‘The rise and rise of the bus industry’, Global Transport 9: 76–9.

BRIAN TURTON

128

Royal Commission on Environmental Pollution (1994) Transport and the Environment, London: HMSO.

Tolley, R.S. (1990) Calming Traffic in Residential Areas, Brefi: Coachex.

White, P. (1995) ‘Deregulation of local bus services in Britain’, Transport Reviews 15(2): 185–209.

Further reading

D.Banister and K.Button (eds) (1993) Transport, the Environment and Sustainable

Development (London: Spon) contains comprehensive discussions of transport policy and

environmental issues in Britain. R.Gibb (ed.) (1994) The Channel Tunnel: a Geographical

Perspective (Chichester: Wiley) provides a detailed account of the the origins of the Channel

Tunnel and its implications within Britain for tourism, freight and passenger traffic patterns,

industrial location, the environment and regional economic development. B.S.Hoyle and

R.D.Knowles (eds) (1998) Modern Transport Geography, 2nd edn (London: Belhaven)

presents a worldwide perspective but contains numerous illustrations from the United

Kingdom in the context of transport deregulation and privatisation, transport and the

environment, and inter-urban transport. Problems of rural transport are also discuss. R.Tolley

and B.J.Turton (1995) Transport Systems, Policy and Planning: a Geographical Perspective.

(London: Longman) examines the transport system of the United Kingdom along with those

of other industrial nations. Urban transport problems and remedies are discussed, as are the

environmental and social implications of transport in the United Kingdom. Transport

Statistics, Great Britain (annual publication) (London: HMSO) is accepted as the standard

source for data relating to personal travel and road, rail, urban, air and maritime transport.

P.White (1995) Public Transport, 3rd edn (London: UCL Press) offers a detailed account of

all aspects of public transport in Britain, including inter-urban, urban and rural systems.

Passenger transport policy issues are also examined, together with the organisation, control

and technology of the principal modes. Va (1991) ‘British passenger transport into the 1990s’,

Geography 77 (334), Part 1, is a useful review of rail, bus, air and local urban transport

developments.

129

Chapter 7

Manufacturing industry

David Sadler

Introduction

In the second edition of this collection, Bull (1991) highlighted the significance of the late

1970s and early 1980s as a period of major transformation for manufacturing industry in

the United Kingdom. This chapter picks up on that story, focusing in particular on

developments within the manufacturing sector in the UK since the mid-1980s and their

regional implications. It looks first at the record of manufacturing activity during those

years, then goes on to consider two significant aspects of recent debate concerning that

performance. These are the extent and role of foreign direct investment (FDI), and changing

patterns of work organisation and labour relations. It then explores the nature of national

state policies towards the sector, concentrating on some of the consequences of those policies

that have encouraged massive inward flows of foreign direct investment. The evolution of

manufacturing within the UK is increasingly dependent upon such global corporate strategies.

Finally, the conclusions look to the future and seek to consider the implications of events

since the mid-1980s for manufacturing within the UK in the first decade of the next

millennium.

The performance of manufacturing in the UK since the mid-1980s and

its regional implications

It is impossible to understand the recent performance of manufacturing in the UK without

brief reference to a longer-term picture. Employment in manufacturing in the post-1945

period peaked in 1966 at 8.5 million (although in relative terms, as a proportion of the UK

workforce, it peaked in the mid-1950s at around 35 per cent). Since 1966 employment has

declined almost relentlessly, particularly from 1979 to 1981 when over a million jobs were

shed. Output, however, continued to grow until 1973 (so that from 1966 to 1973 there was

DAVID SADLER

130

a period of job-less growth) when it too began to decline, particularly from 1979 to 1981. In

those two years output fell by 17 per cent and capital investment by 30 per cent; the million

jobs lost represented a fall of 16 per cent. After 1981 output and investment both began to

recover, whilst employment continued on a downward path, reaching 5 million by 1985.

Thus the period after 1981 witnessed a second phase of job-less growth.

The immediate causes of the collapse in manufacturing in the UK from the late 1970s to

the early 1980s included a government policy of high interest rates (in pursuit of the control of

inflation and a reduced Public Sector Borrowing Requirement), and a relaxation of financial

controls (which encouraged capital flight from the UK), in a context where a weak

manufacturing base was already struggling to cope with a second deep international recession.

The consequences were dramatic. In 1983 the UK recorded its first-ever balance-of-trade

deficit in finished manufactured goods, and that indicator has remained in deficit to the present

day. Output in real terms did not recover to pre-1979 levels until the late 1980s. Severe

contraction in certain sectors of manufacturing, particularly those under state ownership such

as coal and steel, was reflected in intense regional and sub-regional economic downturns,

especially in the old industrial regions of central Scotland, north-east England and South

Wales. With a concentration of growth in the early to mid-1980s in a broad arc stretching from

the ‘M4 corridor’ between Bristol and London and round to East Anglia, concern was expressed

over the resurgence of a North-South divide, evident in contrasting economic conditions. The

national economy appeared to be in the midst of a major economic transformation, in which

individual places and regions had sharply diverging profiles and prospects.

Around the mid- to late 1980s, there was considerable debate about the underlying

reasons for the poor performance of manufacturing industry in the UK relative to other

countries. Several competing explanations were put forward involving the links between

manufacturing and other sectors of the economy, ranging from (what was seen as) an undue

dominance of the financial services sector, to the nature of the relationship between finance

capital and manufacturing. Some other contrasting explanations stressed labour productivity

and poor management as key explanatory factors, while still others focused on the role of

innovation and R&D, and the under-representation of small firms within the national

economy. Evaluating the causes of the UK’s manufacturing decline became a growth industry

in its own right.

At the same time too, manufacturing in the UK—and the UK economy more generally

—was in the midst of a recovery, albeit one which was hesitant at first. By the close of the

1980s an economic boom, partly engineered by national government policies (in a context

of renewed international growth), had seen manufacturing recover its levels of output of ten

years previously. The cycle peaked at the end of that decade, however, and a slump set in

again in the early 1990s, with gradual recovery only apparent in the mid-1990s. This picture

—of boom, bust and recovery, in a setting of long-term decline—underpins the performance

of manufacturing in the UK since the mid-1980s.

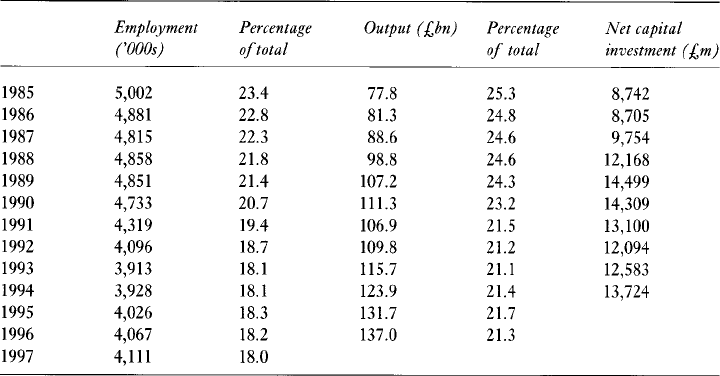

In that period employment in manufacturing initially continued a steady decline, falling

from 5 million in 1985 to 3.9 million in 1993, although it began to reverse that longstanding

trend from 1994 onwards, growing to 4.1 million by 1997 (Table 7.1 and Figure 7.1). Thus

absolute employment in manufacturing contracted during the boom years of the late 1980s—

continuing the phase of job-less growth—and only began a recovery with the conditions of

the mid-1990s. In relative terms however, manufacturing employment contracted continually,

from 23 per cent of the UK’s workforce in 1985 to 18 per cent by 1997.

MANUFACTURING INDUSTRY

131

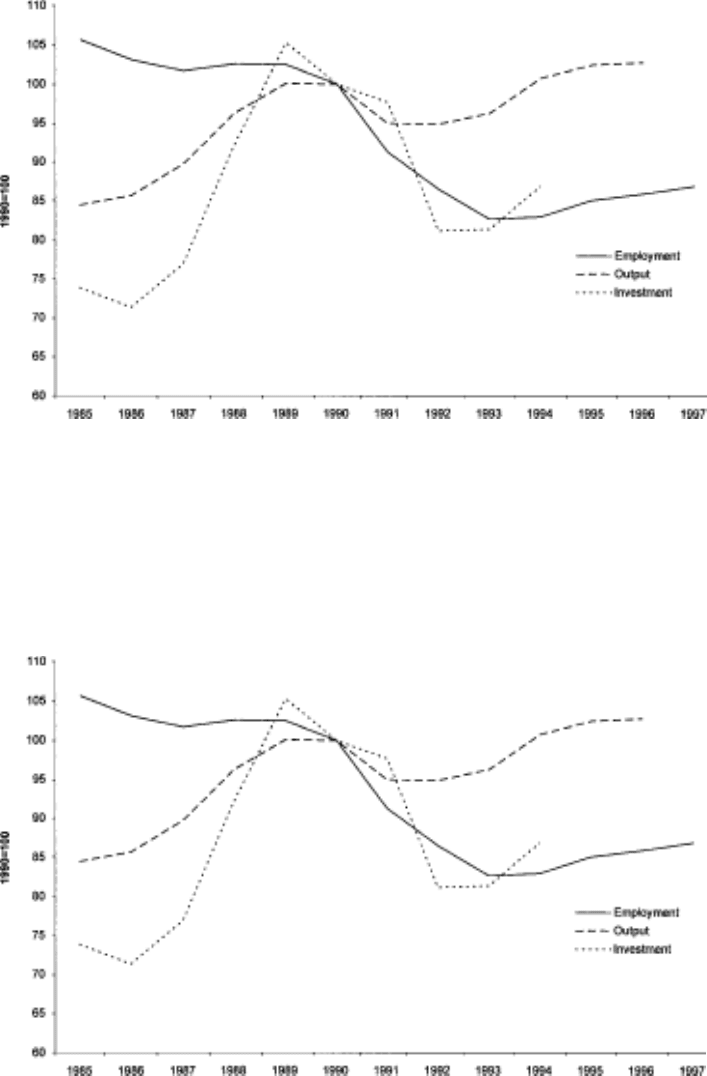

Manufacturing output grew strongly during the late 1980s boom, reaching £111

billion at current costs in 1990 before falling back in 1991 and 1992. When standardised

to 1990 costs though, output peaked in 1989 and it was not until 1994 that it regained

such a level (Figure 7.1). On this basis the extent of the growth in output in the mid- to

late 1980s is clearly apparent, although manufacturing continued to account for a

declining share of national output (falling steadily from 25 per cent in 1985 to 21 per

cent in 1996). An even more marked picture was apparent for investment, which grew

exceptionally strongly from 1986 to 1989, only to fall back just as dramatically from

1990 to 1992.

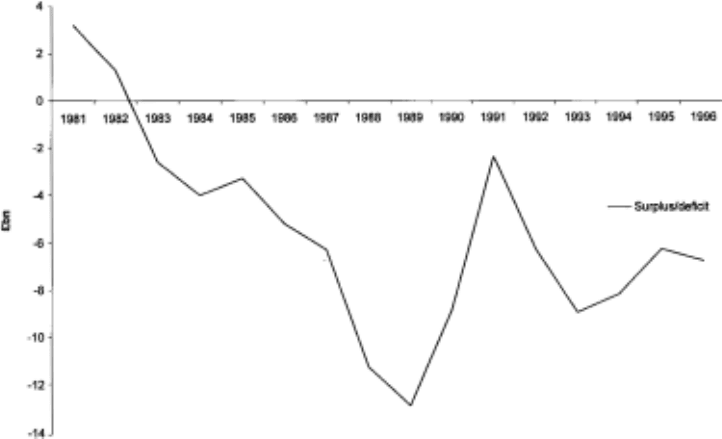

These changes had an impact on the UK’s balance of trade in finished manufactured

goods. One distinctive aspect of the late 1980s boom in the UK economy was the extent to

which it encouraged increased volumes of imports of manufactures, reaching over £60

billion in 1989 and again in 1990 (Figure 7.2). This surge of imports had a devastating

effect on the UK’s trade deficit, which grew markedly to reach £11 billion in 1988 and £13

billion in 1989 (Figure 7.3). The trade deficit in manufactured goods fell back equally

sharply during the early 1990s recession (to £2 billion in 1991) but thereafter expanded

once again, to a range of £6–9 billion during the mid-1990s.

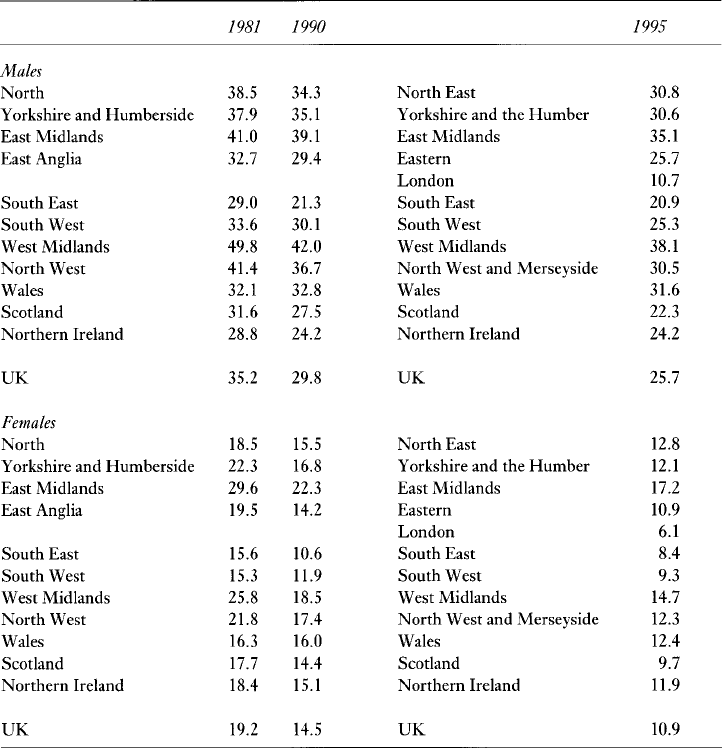

The national changes in employment, output and investment also took on distinctive

regional profiles.

1

Male manufacturing employment as a proportion of the regional total

(Table 7.2) remained at its highest in 1995 in the West Midlands, even though it had fallen

by then to 38 per cent from a level of 50 per cent in 1981. Other regions with a high

proportion in 1995 included the East Midlands (35 per cent) and the North East, Yorkshire

and the Humber, the North West and Merseyside, and Wales, which were all in the range of

30 to 31 per cent—well above the UK average of 26 per cent. Of these, all except Wales had

seen a fall of between seven and eleven percentage points since 1981; by stark contrast, the

TABLE 7.1 Employment, output and investment in manufacturing in the UK, 1985–97

Sources: Calculated from Labour Market Trends; UK National Accounts 1997 (The Blue Book).

Note: 1992 Standard Industrial Classification (SIC)

DAVID SADLER

132

FIGURE 7.1 Employment, output and investment in manufacturing in the UK, 1985–97 (at constant

1990 costs)

FIGURE 7.2 UK imports and exports of finished manufactured goods, 1981–96

MANUFACTURING INDUSTRY

133

relative proportion in Wales remained virtually unchanged during this period. Such was the

extent of the long-term collapse of the manufacturing base in Scotland and Northern Ireland

that throughout this period they had proportions below the UK average. The distinctive

economic structure of the broader south-east of England was reflected in very low proportions

of male manufacturing employment: a bare 11 per cent in London and 21 per cent in the

South East region—well below the UK average.

Female manufacturing employment as a proportion of the regional total was also

highest in 1995 in the West Midlands and the East Midlands, although in this case the

East Midlands had the very highest level of 17 per cent, well above the UK average of

11 per cent (Table 7.2). Regions clearly above the mean included the North East,

Yorkshire and the Humber, the North West and Merseyside, and Wales, which were all

in the range of 12 to 13 per cent. The most severe falls (of between ten and twelve

percentage points) since 1981 had taken place in Yorkshire and the Humber, the East

Midlands, the West Midlands, the North West and Merseyside, and Scotland. Wales had

seen only a limited fall of four percentage points, and that took place in the period after

1990. There were four regions below the UK average: London, the South East, the

South West, and Scotland.

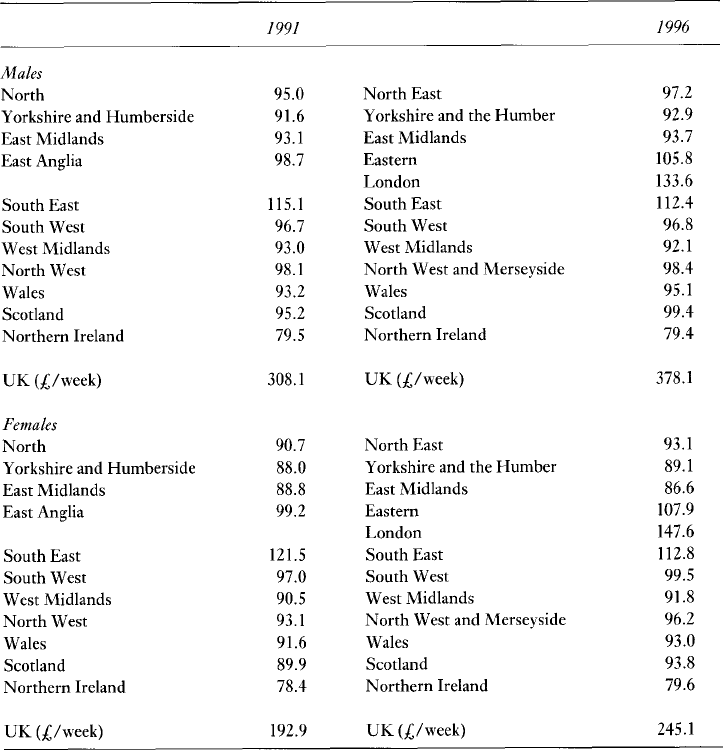

Average weekly male earnings in manufacturing also varied significantly from region

to region (Table 7.3). Only three regions were above the UK average in 1996—London, the

South East and Eastern; all others were within eight percentage points of the mean with the

exception of Northern Ireland, where earnings were just 79 per cent of the UK average.

Several of these regions had converged slightly towards the mean since 1991, with gains of

between one and two percentage points in Yorkshire and the Humber, Wales, and the North

East; Scotland had seen a gain of four percentage points. The West Midlands by contrast

FIGURE 7.3 Balance of trade in finished manufactured goods, 1981–96

DAVID SADLER

134

had slipped slightly further away from the mean. A pattern of even wider inequality was

evident in terms of average weekly female earnings in manufacturing (Table 7.3). The highest

rate, for London at 148 per cent of the UK average, was practically double that for Northern

Ireland at 80 per cent, and two other regions (the East Midlands, and Yorkshire and the

Humber) were below 90 per cent. Most regions, however, had improved their position relative

to the mean since 1991, particularly Scotland which had seen a gain of four percentage

points. The notable exception to this trend was the East Midlands, which had seen a fall of

over two percentage points.

2

Manufacturing output as a proportion of regional Gross Domestic Product in 1995

ranged from 20 per cent in Northern Ireland to 31 per cent in the West Midlands (Table 7.4).

TABLE 7.2 Percentage of employees in manufacturing, by region, 1981, 1990 and 1995

Sources: Regional Trends 26, Table 10.7; Regional Trends 32, Table 5.8.

Note: 1981 and 1990 data, 1980 SIC; 1995 data, 1992 SIC.

MANUFACTURING INDUSTRY

135

It was well above the UK mean of 22 per cent in the North, Yorkshire and Humberside, the

East Midlands, the North West, and Wales (which were all in the range from 26 to 30 per

cent), and markedly below in the South East at 16 per cent. Both Scotland and Northern

Ireland—traditionally regarded as industrial regions—had below-average proportions of

output derived from the manufacturing sector. Put another way, manufacturing was

proportionately most significant to the output of only part of the classic industrial heartland

of the UK—the North of England, Wales and the West Midlands (but excluding Scotland

and Northern Ireland) along with an area less frequently seen in this light, the East Midlands.

The relative position of each region had remained quite constant since 1987, although notable

TABLE 7.3 Average weekly earnings in manufacturing by region, 1991 and 1996

Sources: Calculated from Regional Trends 27, Table 8.5; Regional Trends 32, Table 5.16.

Note: Expressed as a percentage of the UK average (1996) and GB average (1991); 1980 SIC for 1991,

1992 SIC for 1996.