Trent E.M., Wright P.K. Metal Cutting

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

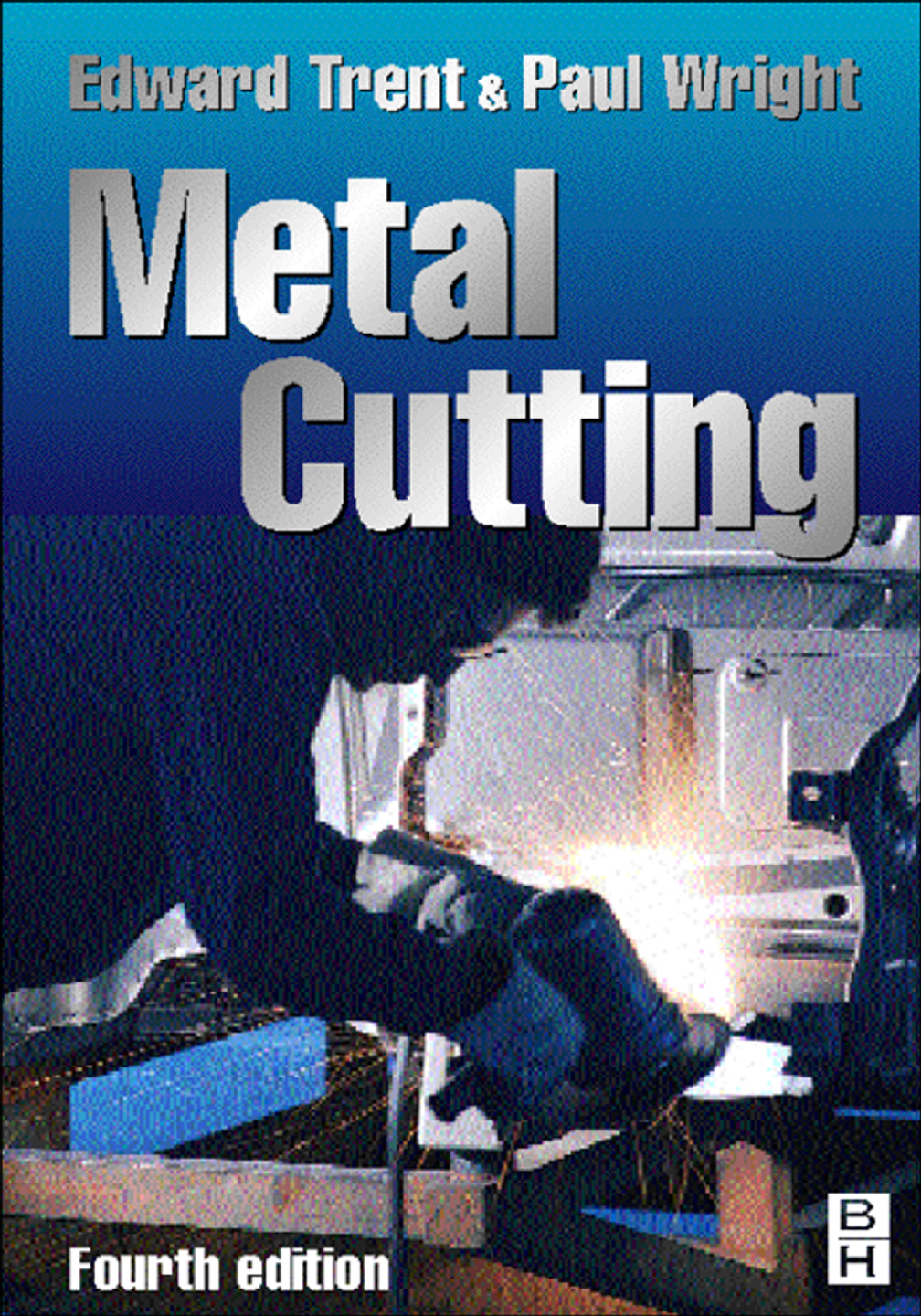

Metal Cutting

Metal Cutting

Fourth Edition

Edward M. Trent

Department of Metallurgy and Materials

University of Birmingham, England

Paul K. Wright

Department of Mechanical Engineering

University of California at Berkeley, U.S.

Boston Oxford Auckland Johannesburg Melbourne New Delhi

Copyright © 2000 by Butterworth–Heinemann

A member of the Reed Elsevier group

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in

any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise,

without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Recognizing the importance of preserving what has been written, Butterworth–Heinemann

prints its books on acid-free paper whenever possible.

Butterworth–Heinemann supports the efforts of American Forests and the

Global ReLeaf program in its campaign for the betterment of trees, forests, and

our environment.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Trent, E. M. (Edward Moor)

Metal cutting / Edward M. Trent, Paul K. Wright.– 4th ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-7506-7069-X

1. Metal-cutting. 2. Metal-cutting tools. I. Wright, Paul Kenneth. II. Title.

TJ1185.T73 2000

671.5’3—dc21

99-052104

The publisher offers special discounts on bulk orders of this book.

For information, please contact:

Manager of Special Sales

Butterworth–Heinemann

225 Wildwood Avenue

Woburn, MA 01801–2041

Tel: 781-904-2500

Fax: 781-904-2620

For information on all Butterworth–Heinemann publications available, contact our World

Wide Web home page at: http://www.bh.com

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Printed in the United States of America

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Foreword ix

Preface xi

Acknowledgements xv

Chapter 1 Introduction: Historical and Economic Context 1

The Metal Cutting (or Machining) Process 1

A Short History of Machining 2

Machining and the Global Economy 4

Summary and Conclusion 7

References 8

Chapter 2 Metal Cutting Operations and Terminology 9

Introduction 9

Turning 9

Boring Operations 12

Drilling 13

Facing 14

Forming and Parting Off 14

Milling 14

Shaping and Planing 16

Broaching 18

Conclusion 19

References 19

Bibliography (Also see Chapter 15) 19

Chapter 3 The Essential Features of Metal Cutting 21

Introduction 21

vi

The Chip 23

Techniques for Study of Chip Formation 24

Chip Shape 25

Chip Formation 26

The Chip/tool Interface 29

Chip Flow Under Conditions of Seizure 40

The Built-up Edge 41

Machined Surfaces 47

Summary and Conclusion 47

References 55

Chapter 4 Forces and Stresses in Metal Cutting 57

Introduction 57

Stress on the Shear Plane 58

Forces in the Flow Zone 60

The Shear Plane and Minimum Energy Theory 62

Forces in Cutting Metals and Alloys 74

Stresses in the Tool 79

Stress Distribution 80

Conclusion 95

References 95

Chapter 5 Heat in Metal Cutting 97

Introduction 97

Heat In the Primary Shear Zone 98

Heat at the Tool/work Interface 102

Heat Flow at the Tool Clearance Face 112

Heat in Areas of Sliding 113

Methods of Tool Temperature Measurement 114

Measured Temperature Distribution in Tools 121

Relationship of Tool Temperature to Speed 126

Relationship of Tool Temperature to Tool Design 128

Conclusion 130

References 130

Chapter 6 Cutting Tool Materials I: High Speed Steels 132

Introduction and Short History 132

Carbon Steel Tools 133

High Speed Steels 138

Structure and Composition 140

Properties of High Speed Steels 144

Tool Life and Performance of High Speed Steel Tools 149

Tool-life Testing 163

Conditions of Use 166

vii

Further Development 167

Conclusion 173

References 173

Chapter 7 Cutting Tool Materials II: Cemented Carbides 175

Cemented Carbides: an Introduction 175

Structures and Properties 176

Tungsten Carbide-Cobalt Alloys (WC-Co) 177

Tool Life and Performance of Tungsten Carbide-Cobalt Tools 186

Tungsten-Titanium-Tantalum Carbide Bonded with Cobalt 202

Performance of (WC+TiC+TaC) -Co Tools 205

Perspective: “Straight” WC-Co Grades versus the “Steel-Cutting” Grades 209

Performance of “TiC Only” Based Tools 210

Performance of Laminated and Coated Tools 211

Practical Techniques of Using Cemented Carbides for Cutting 215

Conclusion on Carbide Tools 224

References 225

Chapter 8 Cutting Tool Materials III: Ceramics, CBN Diamond 227

Introduction 227

Alumina (Ceramic) Tools 227

Alumina-Based Composites (Al

2

O

3

+ TiC) 229

Sialon 231

Cubic Boron Nitride (CBN) 236

Diamond, Synthetic Diamond, and Diamond Coated Cutting Tools 239

General Survey of All Tool Materials 245

References 249

Chapter 9 Machinability 251

Introduction 251

Magnesium 252

Aluminum and Aluminum Alloys 254

Copper, Brass and Other Copper Alloys 258

Commercially Pure Iron 269

Steels: Alloy Steels and Heat-Treatments 269

Free-Cutting Steels 278

Austenitic Stainless Steels 290

Cast Iron 293

Nickel and Nickel Alloys 296

Titanium and Titanium Alloys 303

Zirconium 307

Conclusions on Machinability 307

References 309

viii

Chapter 10 Coolants and Lubricants 311

Introduction 311

Coolants 313

Lubricants 322

Conclusions on Coolants and Lubricants 334

References 337

Chapter 11 High Speed Machining 339

Introduction to High Speed Machining 339

Economics of High Speed Machining 340

Brief Historical Perspective 341

Material Properties at High Strain Rates 343

Influence of Increasing Speed on Chip Formation 348

Stainless Steel 352

AISI 4340 359

Aerospace Aluminum and Titanium 360

Conclusions and Recommendations 363

References 368

Chapter 12 Modeling of Metal Cutting 371

Introduction to Modeling 371

Empirical Models 373

Review of Analytical Models 374

Mechanistic Models 375

Finite Element Analysis Based Models 382

Artificial Intelligence Based Modeling 397

Conclusions 404

References 406

Chapter 13 Management of Technology 411

Retrospective and Perspective 411

Conclusions on New Tool Materials 412

Conclusions on Machinability 414

Conclusions on Modeling 416

Machining and the Global Economy 417

References 422

Chapter 14 Exercises For Students 425

Review Questions 425

Interactive Further Work on the Shear Plane 434

Bibliography and Selected Web-sites 435

Index 439

FOREWORD

Dr. Edward M. Trent who died recently (March, 1999) aged 85, was born in England, but was

taken to the U.S.A. as a baby when his parents emigrated to Pittsburgh and then to Philadelphia.

Returning to England, he was a bright scholar at Lansdowne High School and was accepted as a

student by Sheffield University in England just before his seventeenth birthday, where he studied

metallurgy. After his first degree (B.Sc.), he went on to gain his M.Sc. and Ph.D. and was awarded

medals in 1933 and 1934 for excellence in Metallurgy. His special research subject was the

machining process, and he continued in this work with Wickman/Wimet in Coventry until 1969.

Sheffield University recognized the importance of his research, and awarded him the degree of

D.Met. in 1965.

Prior to the 1950’s, little was known about the factors governing the life of metal cutting tools. In

a key paper, Edward Trent proposed that the failure of tungsten carbide tools to cut iron alloys at

high speeds was due to the diffusion of tungsten and carbon atoms into the workpiece, producing a

crater in the cutting tool, and resulting in a short life of the tool. Sceptics disagreed, but when tools

were covered with an insoluble coating, his ideas were confirmed. With the practical knowledge he

had gained in industry, and his exceptional skill as a metallographer, Edward Trent joined the

Industrial Metallurgy Department at Birmingham University, England in 1969 and was a faculty

member there until 1979. Just before his retirement, he was awarded the Hadfield Medal by the

Iron and Steel Institute in recognition of his contribution to metallurgy.

Edward Trent was thus a leading figure in the materials science aspects of deformation and metal

cutting. As early as 1941, he published interesting photomicrographs of thermoplastic shear bands

in high tensile steel ropes that were crushed by hammer blows. One of these is reproduced in Fig-

ure 5.6 of this text. Such studies of adiabatic shear zones naturally led him onward to the metal

cutting problem. It is an interesting coincidence that also in the late 1930s and early 1940s, another

leader in materials science, Hans Ernst, curious about the mechanism by which a cutting tool

removes metal from a workpiece, carried out some of the first detailed microscopy of the process

of chip formation. He employed such methods as studying the action of chip formation through the

x FOREWORD

microscope during cutting, taking high-speed motion pictures of such, and making photomicro-

graphs of sections through chips still attached to workpieces. As a result of such studies, he

arrived at the concept of the “shear plane” in chip formation, i.e. the very narrow shear zone

between the body of the workpiece and the body of the chip that is being removed by the cutting

tool, which could be geometrically approximated as a plane. From such studies as those by

Ernst, Trent and others, an understanding emerged of the geometrical nature of such shear zones,

and of the role played by them in the plastic flows involved in the chip formation process in

metal cutting. That understanding laid the groundwork for the development, from the mid-1950s

on, of analytical, physics-based models of the chip formation process by researchers such as

Merchant, Shaw and others.

These fundamental studies of chip formation and tool wear, and the metal cutting technology

resulting from it, are still the base of our understanding of the metal cutting process today. As the

manufacturing industry builds on the astounding potential of digital computer technology, born

in the 1950s, and expands to Internet based collaboration, the resulting global enterprises still

depend on the “local” detailed fundamental metal cutting technology if they are to obtain

increasingly precise products at a high quality level and with rapid throughput. However, one of

the most important strengths that the computer technology has brought to bear on this situation is

the fact that it provides powerful capability to integrate the machining performance with the per-

formance of all of the other components of the overall system of manufacturing. Accomplish-

ment of such integration in industry has enabled the process of performing machining operations

to have full online access to all of the total database of each enterprise’s full system of manufac-

turing. Such capability greatly enhances both the accuracy and the speed of computer-based

engineering of machining operations. Furthermore, it enables each element of that system (prod-

uct design, process and operations planning, production planning and control, etc.), anywhere in

the global enterprise to interact fully with the process of performing machining and with its tech-

nology base. These are enablements that endow machining technology with capability not only

to play a major role in the functioning and productivity of an enterprise but also to enable the

enterprise as a whole to utilize it fully as the powerful tool that it is.

M. Eugene Merchant and Paul K. Wright, June 1999