Teodorescu P.P. Mechanical Systems, Classical Models Volume I: Particle Mechanics

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

MECHANICAL SYSTEMS, CLASSICAL MODELS

512

If

00

0 vxλ<< , then the particle starts from

0

P , reaches A at the moment

000

/( )tv xvλλ

′

=− and then changes of direction and tends to infinity in the

negative direction of the

Ox -axis (Fig.8.39,a); the diagram of motion has a maximum

for

tt

′

=

and pierces the Ot -axis at

000

/( )tx xvλ

′

′

=

− (Fig.8.39,b). If

00

vxλ≥ ,

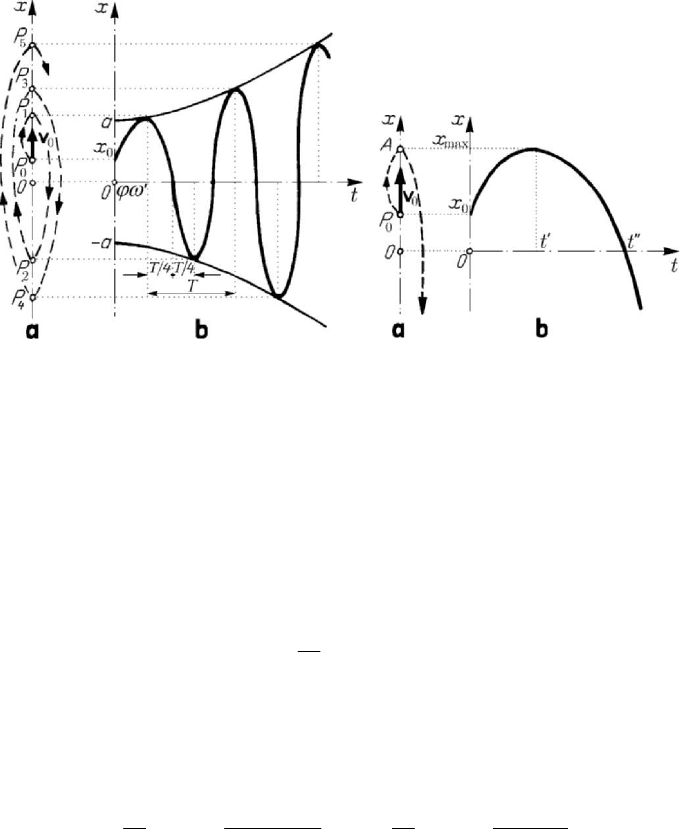

Figure 8.38. Self-sustained motion of a particle; Figure 8.39. Self-sustained motion of a

subcritical damping. Trajectory (a); particle; critical damping, case

diagram

()xt vs t (b).

00

0 vxλ

<

< : trajectory (a);

diagram

()xt vs t (b).

then the particle starts from

0

P and tends to infinity in the positive direction of the Ox -

axis (Fig.8.35,a), the diagram of motion being that of Fig.8.35,b. If

0

0v ≤ , then the

particle tends to infinity in the negative direction of the

Ox -axis (Fig.8.40,a), while the

diagram of motion pierces the

Ot -axis at tt

′

′

=

(Fig.8.40,b). Analogously, for ωλ<

(supercritical damping,

1χ > ) we obtain

000

1

() e cosh ( )sinh

t

xt x t v x t

λ

ωλω

ω

⎡⎤

′

′′′

=+−

⎢⎥

′′

⎣⎦

,

(8.2.39''')

the pseudopulsation ω

′′

being given by (8.2.17). In what concerns the trajectory and

the diagram of motion, we obtain the same qualitative results as

00

0()vxλω

′′

<

<− ,

as

00

()vxλω

′′

≥− or as

0

0v

≤

, respectively (Figs 8.39, 8.35, 8.40); in this case

0

2

00

1

arg tanh

v

t

xv

ω

ω

ωλ

′

′

′

=

′′

−

,

0

00

1

arg tanh

x

t

xv

ω

ωλ

′

′

′′

=

′′

−

.

If the elastic force is repulsive, then the equation of motion has the form

2

20xxxλω

−

−= ,

(8.2.40)

Dynamics of the particle in a field of elastic forces

513

and we are led to

000

1

() e cosh ( )sinh

t

xt x t v x t

λ

ωλω

ω

⎡⎤

=+−

⎢⎥

⎣⎦

,

(8.2.40')

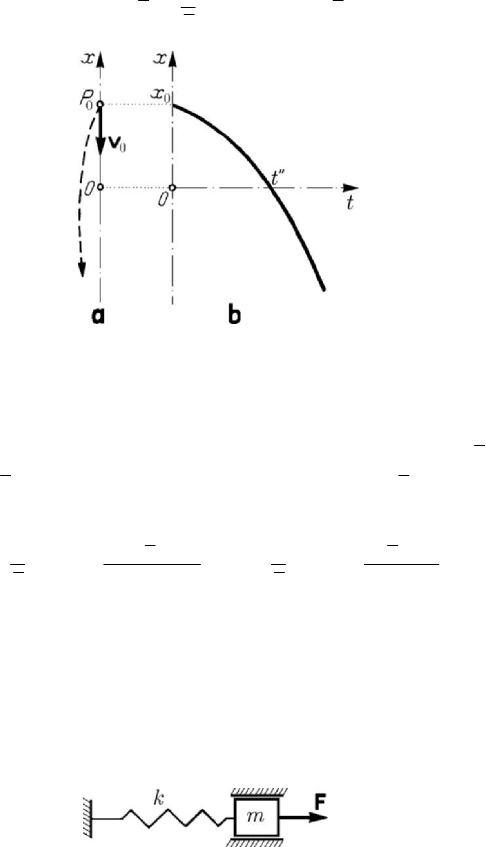

Figure 8.40. Self-sustained motion of a particle; critical damping, case

0

0v ≤ :

trajectory (a); diagram

()xt

vs t (b).

with the same initial conditions and the notation (8.2.18'''). The trajectory and the

diagram of motion are qualitatively given for

0

0v ≥

and for

00

()vxωλ

=

−− in

Fig.8.35, for

00

() 0xvωλ−− < < in Fig.8.36 and for

00

()vxωλ

<

−− in Fig.8.40;

we notice that

0

2

00

1

arg tanh

v

t

vx

ω

ω

λω

−

′

=

+

,

0

00

1

arg tanh

x

t

xv

ω

ωλ

′′

=

−

.

2.2.8 Influence of perturbing forces. Resonance

The intervention of a perturbing force

F

leads to a forced motion (a constraint or

forced oscillation) of a particle

P

, unlike the free motion (free oscillation) considered

till now. The most simple physical model of a mechanical system with a simple degree

of freedom acted upon by such a force is that of a non-damped forced linear oscillator,

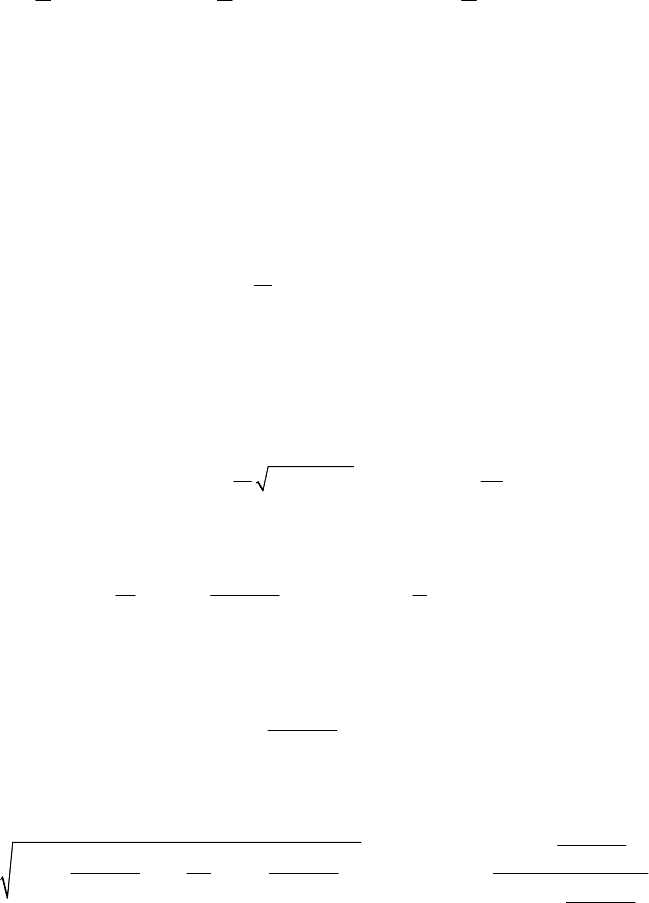

represented in Fig.8.41.

Figure 8.41. Model of a non-damped forced linear oscillator.

Let us consider firstly the case of a periodic force

()FFt

=

, which fulfils the

Lejeune-Dirichlet sufficient conditions, that is which is developable into a Fourier

series

0

11

( ) cos sin ... cos sin ...

nn

F t pt pt npt nptαα α α α

′′′ ′ ′′

=+ + ++ + +,

(8.2.41)

MECHANICAL SYSTEMS, CLASSICAL MODELS

514

where

0

1

()d

T

Ft t

T

α =

∫

,

2

()cos d

n

T

Ft npt t

T

α

′

=

∫

,

2

()sin d

n

T

Ft npt t

T

α

′′

=

∫

,

(8.2.41')

the period

2/Tpπ= on which is effected the integration may begin from a point

arbitrarily chosen. In case of a non-damped linear oscillator subjected to a perturbing

force, the equation of motion is of the form

2

()xxftω+= ,

(8.2.42)

where we use the previous notation and where

1

() ()

f

tFt

m

=

.

(8.2.43)

We notice that the term

0

α in the expansion into a series leads only to a change of

origin for

()xt , so that it may be neglected. For each term of the Fourier series one

obtains a particular integral of the same type, leading to the corresponding motion; it is

thus sufficient to consider the influence of only one term of the form

cos( )ptαϕ− ,

22

111

1

m

αα α α

′

′′

== +

,

arctan

α

ϕ

α

′

′

=

′

.

(8.2.44)

For

() cos( )

f

tptαϕ=−, we find

0

0

22

( ) cos sin cos cos sin sin cos( )

v

p

xt x t t t t pt

p

α

ωω ϕωϕω ϕ

ωω

ω

⎡

⎤

=+− + −−

⎣

⎦

−

,

(8.2.42')

with the initial conditions (8.2.23'); we may also write

22

() cos( ) cos( )xt a t pt

p

α

ωψ ϕ

ω

=−+ −

−

,

(8.2.42'')

where

22

00

22 2 22

cos sin

1

p

ax v

pp

αϕ α ϕ

ωωω

⎛⎞⎛⎞

=− + −

⎜⎟⎜⎟

−−

⎝⎠⎝⎠

,

0

22

0

22

sin

arctan

cos

p

v

p

x

p

αϕ

ω

ψ

αϕ

ω

ω

−

−

=

⎛⎞

−

⎜⎟

−

⎝⎠

.

(8.2.42''')

One observes thus that the motion of the particle may be obtained as an interference of

two harmonic vibrations: the proper vibration (the proper oscillation) of pulsation

ω

Dynamics of the particle in a field of elastic forces

515

and the forced vibration (the forced oscillation) of pulsation

p , as it was shown in

Subsec. 2.2.4. If, in particular, we assume homogeneous initial conditions

(

00

0xv==) and if the phase shift of the perturbing force vanishes ( 0ϕ = ), then it

results

22

() (cos cos )xt pt t

p

α

ω

ω

=−

−

.

(8.2.45)

If the pulsation

p

differs much from the pulsation ω (p ω or p ω ), then the

diagram of motion is that in Fig.8.22 (the case

p ω , hence a proper vibration of

great pulsation “carried” by a forced vibration of small pulsation); we notice that the

maximal elongation of the resultant motion is practically equal to the double of the

amplitude of one of the motions (

(

)

22

max

2/xpαω≅−). If the two pulsations are

close in magnitude, then one obtains the phenomenon of “beats” (Fig.8.23).

If

p ω= , then it results a non-determination in (8.2.45), as well as in (8.2.42'). If

p ω→

, then one obtains at the limit (we use L’Hospital’s theorem)

() sin

2

xt t t

α

ω

ω

= ,

(8.2.46)

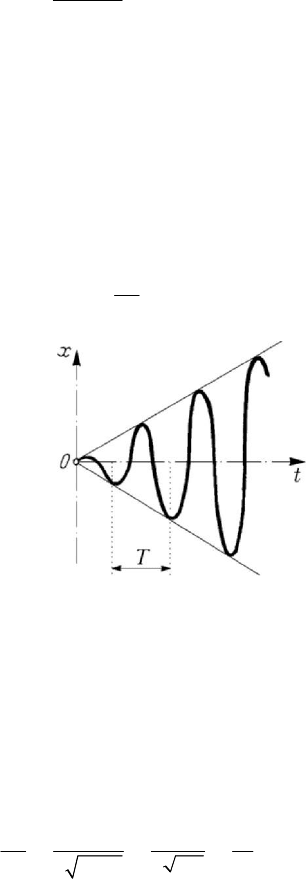

Figure 8.42. Phenomenon of resonance. Diagram ()xt vs

t

.

for the law of motion (8.2.45). In case of the equation of motion (8.2.42') we get an

analogous result (supplementary harmonic vibrations are added). The diagram of

motion (8.2.46) is a sinusoid of amplitude modulated along the straight lines

/2xtαω=± and of pseudoperiod 2/T πω

=

(Fig.8.42). The amplitude increases

very much, in arithmetic progression, and the phenomenon is called resonance, being

extremely dangerous for civil and industrial constructions or for engine building; the

increasing velocity of the amplitude is given by the slope

1

11

/

2

2

2/

c

Fm

FF

k

km

km

α

ω

===

′

,

(8.2.47)

hence it is in direct proportion to the amplitude

11

Fm mαα

=

= of the perturbing

force and in inverse proportion to the critical coefficient of damping (8.2.14). If

MECHANICAL SYSTEMS, CLASSICAL MODELS

516

2

st

11

//xFkFmω== is the static displacement produced by the force

1

F

(corresponding to the relation of proportionality between the elastic force and the

displacement), then we may express the amplitude

A of the forced vibration in the

form

st

Ax=

A

, A being an amplification factor of the forced vibration, given by

22 2

11

1/ 1p ωη

==

−−

A

,

(8.2.48)

where we have introduced the relative pulsation

p

η

ω

=

,

(8.2.48')

Figure 8.43. Phenomenon of resonance. Diagram A vs η .

which is a non-dimensional ratio. The diagram of the absolute value

A

is given in

Fig.8.43.

Figure 8.44. Model of a viscous damped forced linear motion.

If a viscous damping intervenes, then we use the physical model in Fig.8.44, being

led to the equation of motion

2

2cosxxx ptλω α++= ,

(8.2.49)

with the previously introduced notations (for the sake of simplicity, we assumed

0ϕ = ). To fix the ideas, we assume to be in the case of a subcritical damping ( 1χ < );

the motion of the particle is given by

Dynamics of the particle in a field of elastic forces

517

12

() e cos( ) cos sin

t

xt a t C pt C pt

ω

ωψ

′

−

′

=−++

,

(8.2.49')

where

(

)

()

22

1

2

22 22

4

p

C

pp

ωα

ωλ

−

=

−+

,

()

2

2

22 22

2

4

p

C

pp

λα

ωλ

=

−+

,

(8.2.49'')

the last two terms corresponding to the forced motion. Taking into account the

exponential term, the proper motion is rapidly damped, so that we may consider the

forced motion in the form

() cos( )xt A pt ϕ

=

− ,

(8.2.50)

Figure 8.45. Viscous damped forced linear motion. Diagram A vs η.

with

()

2

22 22

4

A

pp

α

ωλ

=

−+

,

22

2

arctan

p

p

λ

ϕ

ω

=

−

.

(8.2.50')

Using the notations introduced above and the damping factor (8.2.14'), we may also

write

MECHANICAL SYSTEMS, CLASSICAL MODELS

518

()

2

222

1

14ηχη

=

−+

A ,

2

2

arctan

1

χη

ϕ

η

=

−

.

(8.2.50'')

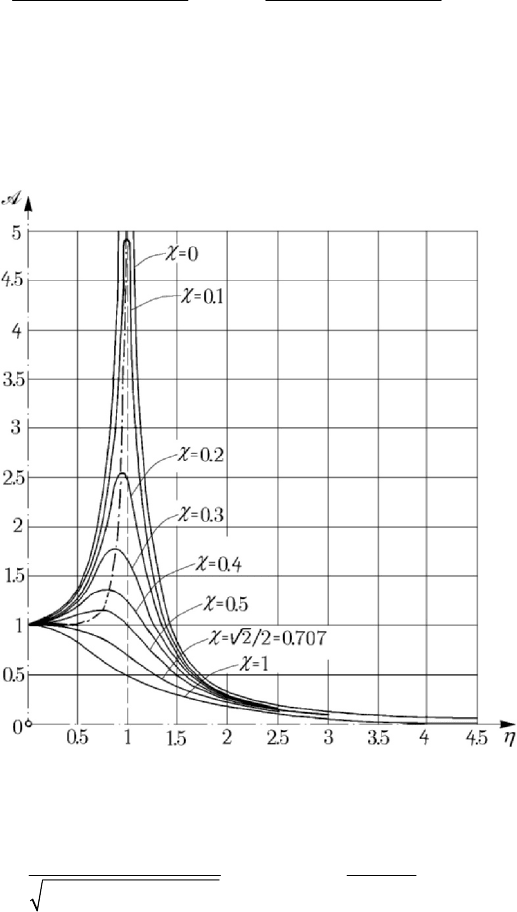

The diagram of the amplification factor

()η

=

A

A is given in Fig.8.45 for various

values of the damping factor

χ . We define a resonance in amplitude for the values

2

res

12 1ηη χ==−<, 1/ 2χ ≤ ,

(8.2.51)

for which the amplification factor has a maximum

max

2

11

2

21

χ

χχ

=>

−

A .

(8.2.51')

One observes that, in case of the phenomenon of resonance, the amplitude is as smaller

as the damping is greater, the diagram of the function being planished for a great

damping; the effect of damping appears especially in the vicinity of the resonance zone

(

1η ≅ ). If the damping is very small ( 1χ ), then the resonance in amplitude

appears for

1η ≅ , the amplification factor being given by

max

1/2χ≅

A

.

Eliminating

χ between (8.2.51) and (8.2.51'), we get

4

max res

1/ 1 η=−A , that one

being the locus of the points of maximum of the diagrams for various values of

χ

(represented by a dot-dash line). These points are at the left of the line

1η = ; on this

line one has

1/2χ=

A

.

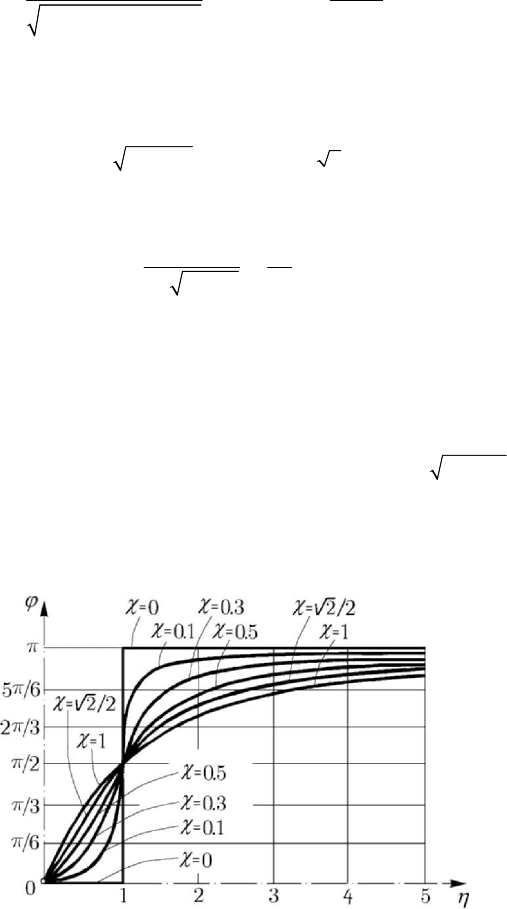

Figure 8.46. Viscous damped forced linear motion. Diagram ϕ vs η.

The diagram of the phase function

()ϕϕη

=

is given in Fig.8.46 for various values

of the coefficient

χ . We notice that, in case of a non-damped system, the phase is

0ϕ = , under the resonance ( 1η

<

), the vibration being in phase with the perturbing

Dynamics of the particle in a field of elastic forces

519

force, or

ϕπ= , over the resonance ( 1η > ), the vibration being in phase opposition

with respect to the perturbing force; in case of a damped system there exists always a

phase shift between the perturbing force and the vibration. For

1η

<

, as χ (hence, the

damping) increases, so the phase shift between the motion and the perturbing force

increases too, the motion remaining behind that force. For

1η > , as χ (hence, the

damping) increases, so the phase shift decreases, the motion remaining behind the

perturbing force too. For a very great

η , the phase shift increases no matter the

damping and the motion tends to be in opposition with the perturbing force. But the

opposition is obtained rigorously only in the absence of the damping (

0η = ). For

1η = one obtains /2ϕπ= for all the damping coefficients χ ; one may define thus a

phase resonance for which the vibration is in quadrature with the perturbing force.

Starting from the equation of motion

1

cosmx k x kx F pt

′

+

+=

(8.2.52)

and multiplying by

x , we get

2

1

d

() cos

d

TV kx Fx pt

t

′

+=− +

;

(8.2.53)

it is thus seen that the mechanical energy does not remain constant, because the second

member of this relation is – in general – non-zero. If we equate this member to zero,

assuming that

0x N , we find

1

0

sin

F

xx pt

kp

=+

′

;

(8.2.53')

hence, the amplitude of the motion is

1

/Fkp

′

, corresponding to the amplitude

resonance (

1/2χ=

A

for

1η

=

).

2.2.9 Mechanical impedance. Transmissibility

Using the complex representation in Subsec. 2.2.3, we can write the equation of

motion (8.2.52) in complex form

mz k z kz F

′

+

+= ,

(8.2.54)

where we denoted

i

0

e

pt

zz=

and

i

1

e

pt

FF=

; replacing

izpz

=

,

2

zpz=− , we may

write

FZz

=

, (8.2.55)

where we have introduced the mechanical impedance

2

iZkmp kp

′

=− + ,

(8.2.55')

MECHANICAL SYSTEMS, CLASSICAL MODELS

520

which is a constant of proportionality, extending thus the notion of elastic constant. For

an elastic spring, the impedance is

Zk

=

, for a mass m we may write

2

Zmp=− ,

while for a linear (viscous) damping it results

iZkp

′

=

. We notice that the equation

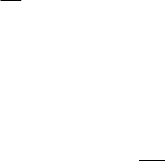

(8.2.54) may be obtained as a sum of vectors in the complex plane (Fig.8.47).

Projecting on the direction of the force

F

and on a normal to it, one finds again the

amplitude

A and the phase shift ϕ given by (8.2.50'). Using the analogy with the

constants corresponding to elastic springs (see Subsec. 2.2.1) and the formulae (8.2.25),

(8.2.25'), we can express the impedance equivalent to

n impedances

i

Z

, 1,2,...,in= ,

linked in parallel, in the form

1

n

i

i

ZZ

=

=

∑

,

(8.2.56)

while for the impedance equivalent to the same impedances linked in series we may

write

1

1

1

n

i

i

Z

Z

=

=

∑

.

(8.2.56')

Figure 8.47. Viscous damped forced linear motion. Complex representation.

An examination of the physical model of a mechanical system constituted of an

elastic spring and a linear damper which act in parallel on a mass (Fig.8.44) leads to the

notion of transmissibility as the ratio

T

C between the amplitude of the force

()Ft kx kx

′

=+ transmitted to the fixed element and the amplitude of the perturbing

force

()Ft which acts upon the mass m . Introducing the impedance iZk kp

′

=+ ,

2

iZkmp kp

′

=− + , it results

()

222

2

222

T

Z

kkp

C

Z

kmp kp

′

+

==

′

−+

;

with the aid of the previous notations, we may also write

()

22

2

222

14

14

T

C

χη

ηχη

+

=

−+

.

(8.2.57)

Dynamics of the particle in a field of elastic forces

521

The transmissibility curves are given in Fig.8.48 for various values of the damping

coefficient

η . The maximal force transmitted to the fixed element is greater than the

amplitude of the perturbing force if

1

T

C > , hence for 02η<< , is less than this

amplitude if

1

T

C < , hence for 2η > , or is equal to the respective amplitude if

1

T

C = , hence if 0η = or 2η = . We notice also that for 2η < the damping

diminishes the transmissibility, while for

2η > that one becomes smaller together

with the damping.

Figure 8.48. Transmissibility curves. Diagram

T

C vs η .

2.2.10 Electro-mechanical analogy

Let be an R.L.C. circuit, constituted of an ohmic resistance

R , a loading inductance

L

and a condenser of capacity

C

, connected in series with a generator having an

electromotive force

()Et (Fig.8.49). This force begins to act at the moment

0t =

,

when we close the circuit; for

0t >

a current of intensity () ()it qt

=

, where ()qt is

the charge, is established.

Choosing as unknown function of the problem the charge

()qt , we may write the

differential equation of second order with constant coefficients