Teodorescu P.P. Mechanical Systems, Classical Models Volume I: Particle Mechanics

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

MECHANICAL SYSTEMS, CLASSICAL MODELS

260

obviously, it is necessary to specify also some laws of variation of those efforts. To do

this, we consider an element of the bar axis of length

ds , reducing thus all the forces

with respect to the axis’ points, corresponding to the cross sections on which act these

forces; as well, we suppose that the bar is acted upon only by distributed forces

pds

and by distributed moments

mds , for which

=++p ppp

τν

β

τνβ,

=

++m

t

mm m

ν

β

τ

νβ. (4.2.35')

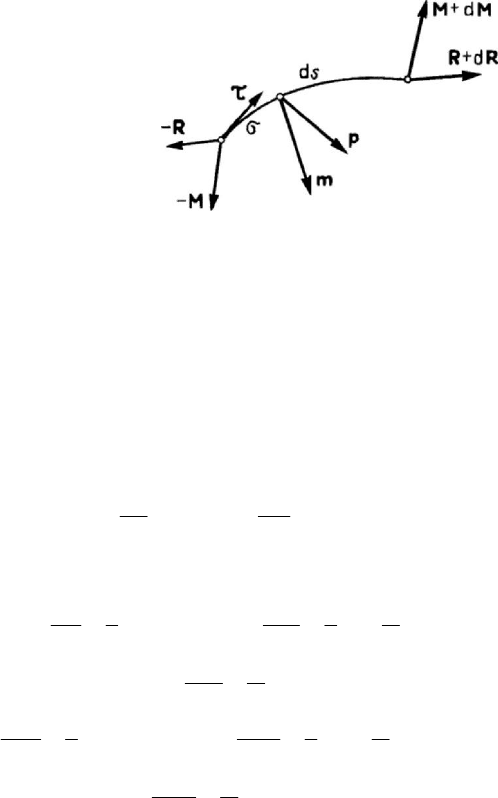

Figure 4.34. Equilibrium of an element of bar.

Equating to zero the torsor of all the forces which act upon this bar element (Fig.4.34),

we obtain

−

++ + =RR Rp 0(d)ds ,

−+ + + + × + + × =

∫

MM Mm R R p 0

d

0

(d)d(d)(d) ()()d

s

ss σσσττ.

Applying a mean value formula to the above integral and neglecting the terms of higher

order, there results

+=

R

p0

d

ds

,

+

×+ =

M

Rm 0

d

ds

τ .

(4.2.36)

Taking into account Frenet’s formulae given in Subsec. 1.1.3, we get

−+=

d1

0

d

N

Tp

s

ντ

ρ

,

+

++=

′

d11

0

d

T

NTp

s

ν

ν

β

ρρ

,

−

+=

′

d

1

0

d

T

Tp

s

β

ν

β

ρ

,

(4.2.37)

d

1

0

d

t

M

Mm

s

ντ

ρ

−+=,

d1 1

0

d

t

M

MMTm

s

ν

ν

ββ

ρρ

+

+−+=

′

,

−

++ =

′

d

1

0

d

M

MTm

s

β

νν

β

ρ

.

(4.2.37')

With the aid of the first two equations (4.2.37) one can express the efforts

T

ν

and T

β

as functions of the given external loads and the normal force

N ; replacing in the third

Statics

261

equation, we get a differential equation of the third order in

N , which may determine

the latter effort. Analogously, the equations (4.2.37') lead to a differential equation of

the same order for the moment of torsion

t

M which contains the axial force N too,

now known; we mat determine thus all six efforts.

In the case of a plane curved bar

′

→1/ 0ρ ,

β

being the unit vector normal to the

plane of the bar; we get

−+=

d1

0

d

N

Tp

s

ντ

ρ

,

+

+=

d1

0

d

T

Np

s

ν

ν

ρ

,

+

=

d

0

d

T

p

s

β

β

,

(4.2.38)

d

1

0

d

t

M

Mm

s

ντ

ρ

−+=,

d1

0

d

t

M

MT m

s

ν

ν

β

ρ

+

−+ =,

+

+=

d

0

d

M

Tm

s

β

ν

β

.

(4.2.38')

One of the efforts

N and T

ν

may be eliminated between the first two equations

(4.2.38), obtaining thus a differential equation of the second order in the other effort;

the third equation allows the computation of the shearing force

T

β

. These efforts being

obtained, one can make analogous considerations for the subsystem (4.2.38').

If the plane curved bar is acted upon by forces contained in its plane, then one has

= 0p

β

, ==0mm

τν

, and, taking into account the Theorem 4.2.4 (the resultant of

the external forces is contained in the plane of the bar axis, while the resultant moment

of these forces is normal to this plane) one gets

=

0T

β

,

=

= 0

t

MM

ν

too; the

remaining equations are

−+=

d1

0

d

N

Tp

s

ντ

ρ

,

+

+=

d1

0

d

T

Np

s

ν

ν

ρ

,

+

+=

d

0

d

M

Tm

s

β

ν

β

,

(4.2.39)

and one makes observations analogous to those above.

If the plane curved bar is acted upon by forces normal to its plane, then we have

==0pp

τν

, = 0m

β

, and, on the basis of the same theorem (the external forces

constitute a system of parallel forces), we obtain

=

0N ,

=

0T

ν

, = 0M

β

; the

system of equations becomes

+=

d

0

d

T

p

s

β

β

,

d

1

0

d

t

M

Mm

s

ντ

ρ

−+=,

d1

0

d

t

M

MT m

s

ν

ν

β

ρ

+

−+ =, (4.2.40)

and may be analogously studied.

Starting from the two particular cases considered above, we obtain the solution

corresponding to the general case, by superposing the effects.

In the case of straight bars, the direction of the binormal and the direction of the

principal normal are not determined; it is convenient to use a right-handed fixed

orthonormed frame of reference

123

Ox x x

, the axis

3

Ox

being along the bar axis

MECHANICAL SYSTEMS, CLASSICAL MODELS

262

(

→1/ 0ρ and =

3

ddsx). Corresponding to the conventions in technical mechanics

of deformable solids (strength of materials), the components of the torsor of internal

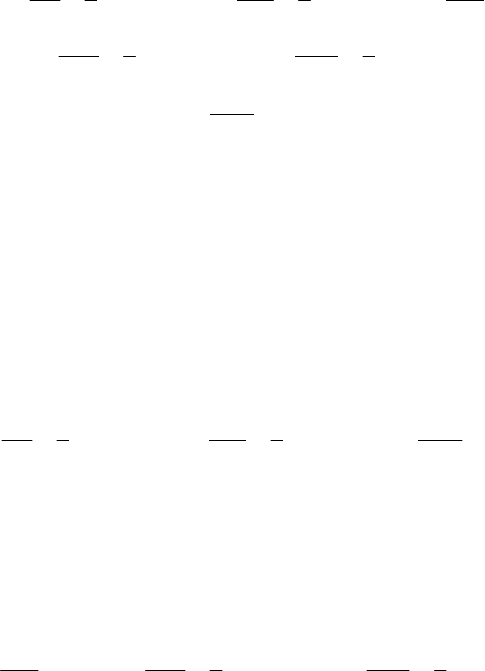

forces are of the form (Fig.4.35,a,b)

Figure 4.35. Efforts on a cross section of a straight bar: force components (a)

and moment components (b).

=− + +Riii

21 12 3

TTN,

=

++Mi i i

11 22 33

MMM, (4.2.41)

and the external load is given by

=

pi

j

j

p ,

=

mi

j

j

m , (4.2.41')

where

i

j

,

=

1, 2, 3j

, are the unit vectors of the co-ordinate axes. We obtain the

relations

+=Rp0

,3

,

+

×+ =MiRm0

,3 3

(4.2.42)

or, in components,

−=

2,3 1

0Tp ,

+

=

1,3 2

0Tp ,

+

=

,3 3

0Np , (4.2.42')

−

+=

1,3 1 1

0MTm ,

−

+=

2,3 2 2

0MTm ,

,3 3

0

t

Mm

+

= . (4.2.42'')

Eliminating the shearing forces, we get

++=

1,33 1,3 2

0Mmp,

+

−=

2,33 2,3 1

0Mmp. (4.2.43)

In the case of external loads contained in the plane

13

Ox x , we have =

2

0p ,

==

13

0mm ; there results

=

1,3

0T ,

−

=

1,3 1

0MT ,

,3

0

t

M

=

,

Statics

263

wherefrom

==

0

11

constTT , =+

00

113 1

MTxM, =

0

1

constM ,

0

const

tt

MM==

(4.2.44)

and

=

2,3 1

Tp,

=

−

2,3 2 2

MTm,

=

−

2,33 1 2,3

Mpm. (4.2.44')

If we have too

=

2

0m , then we may write

=

2,3 1

Tp,

=

2,3 2

MT, (4.2.45)

so that

=

2,33 1

Mp. (4.2.45')

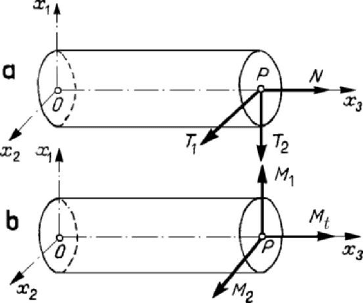

In this case, the diagrams of efforts are, e.g., (Fig.4.36), where we have put into

evidence the correspondence between the point of extremum for the bending moment

and the point at which the shearing force vanishes; we notice also the correspondence

between the inflexion point of the diagram of bending moments, the point of extremum

of the diagram of shearing forces and the point at which the diagram of normal loadings

vanishes, as well as the correspondence between the point of inflexion of the diagram of

shearing forces and the point of extremum of the diagram of normal loadings.

Sometimes, the positive part of the diagram of bending moments is plotted under the

axis (to be in concordance with the deflection line of the bar axis).

Figure 4.36. Diagrams of efforts in a straight bar acted upon by loads in a plane.

In the case of loads contained in the plane

23

Ox x (

=

1

0p ,

=

=

23

0mm ) we can

make analogous observations.

We notice that, in all considerations made in this subsection, the bar is reduced to

its axis; as a matter of fact, so it is for all problems concerning the efforts on the

cross section. This is a mathematical model, which is used currently in technical

mechanics of solids.

MECHANICAL SYSTEMS, CLASSICAL MODELS

264

In the case of external concentrated loads (e.g., concentrated forces), the above

relations remain valid if the usual functions are replaced by distributions, the operations

of differentiation being effected in the same sense too. For instance, in the case of a

straight bar acted upon by a concentrated force

()

(

)

=δ −

0

13 3 3

px P x x

(4.2.46)

at the point of co-ordinate

0

3

x , the equations (4.2.45) lead to

()

(

)

00

23 3 3 2

Tx P x x Tθ=−+,

()

()

(

)

0000

23 3 3 3 3 23 2

Mx Px x x x Tx Mθ=− −++

;

(4.2.46')

the shearing force and the bending moment at the cross section

=

3

0x are thus put in

evidence.

2.1.8 Articulated systems

An articulated system is a structure of bars (a system of rigid solids) linked by

articulations, so as to form a non-deformable system from a geometric point of view (not

a mechanism); the loads are supposed to be applied at the nodes.

By definition, for a bar between two articulations, all the given and constraint forces,

can be reduced to resultants at each extremity of it; for equilibrium, the two resultants

must be directed along the straight line connecting the articulations, having the same

modulus and opposite directions. Hence, from a statical point of view, a bar requires

only one unknown: the corresponding axial force.

The theoretical articulations at the nodes cannot be practically realized. The nodes

are more or less rigid in the case of constructions in concrete or metal; these rigidities

introduce secondary efforts, which may be computed separately. As well, if the bars are

acted also transversally (for instance, by their own weight), one calculates the resultants

at the nodes, while the effect of the other efforts (for instance of bending) are separately

computed.

Starting from the most simple non-deformable geometric construction formed by

articulated bars (the triangle, which has three nodes and three bars), one can constitute a

plane articulated system. By complete induction, one can show that between the number

b of bars and the number n of nodes takes place the relation

=

+23nb , (4.2.47)

which represents a necessary condition for the geometric non-deformability of the plane

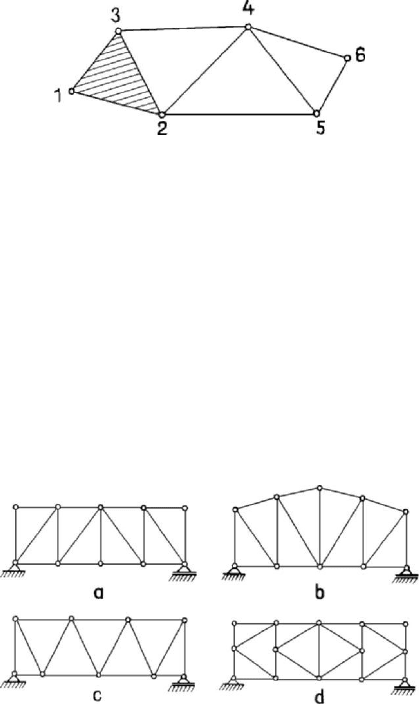

articulated system; thus, a plane articulated system 1-2-…-6, constructed starting form a

basic triangle 1-2-3, is shown in Fig.4.37. On the other hand, a system must be

analysed, from case to case, to see if it is not a system of critical form (at least partially),

the form of which may be lost under the action of a particular system of external loads;

we will not deal with such articulated systems.

Statics

265

A free articulated system, as that considered above, can be fixed in its plane with the

aid of three simple constraints (a hinge and a simple support or three simple supports of

non-concurrent directions at the nodes. Because a simple support is equivalent to a

pendulum (a bar), the relation (4.2.47) has the more general form

Figure 4.37. The setting up of a plane articulated system.

=

+2nbs, ≥ 3s , (4.2.47')

where

s is the number of simple supports. If

=

3s , then the plane articulated system

(structure) constitutes a single geometrically non-deformable body, by suppressing the

supports, and is called a free articulated system (structure).

If we are isolating each node (sectioning all the bars around the node), then the given

and the constraint forces, as well as the efforts in bars form a system of concurrent

forces; writing two equations of equilibrium for each node we obtain

2n equations. If

the relation (4.2.47') holds, then the articulated system is statically determinate (on the

basis of the Kronecker-Capelli theorem for systems of linear algebraic equations); if

<+2nbs, then the articulated system is statically indeterminate, while if

>+2nbs, then the system is a mechanism (geometrically deformable).

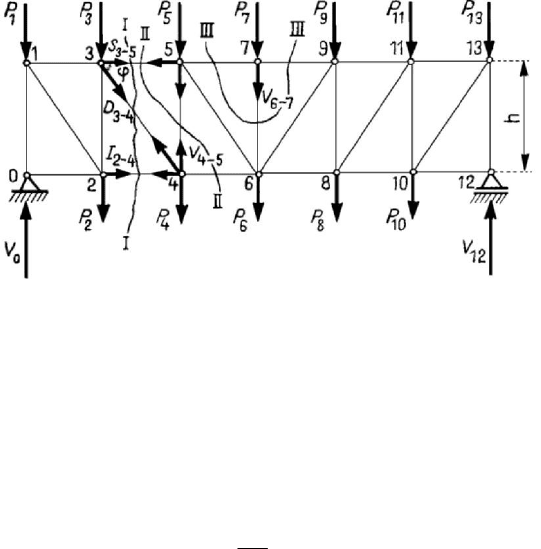

Figure 4.38. Rectangular system (a), trapezoidal system (b), triangular system (c)

and

K

lattice (d) framework.

A plane articulated system may – often – play, in its totality, the rôle of a bar, which

is called truss (framework). The bars of the contour (excepting the lateral ones) are

called flanges; according to their positions, we distinguish between superior and

inferior flanges. The bars linking the flanges are called members (lattices); the vertical

lattices are called vertical members, while the inclined ones are called diagonals. We

denote the axial force in the bar of the framework by

,,SIV or D if this one is a

superior or inferior flange, a vertical member or a diagonal, respectively. According to

MECHANICAL SYSTEMS, CLASSICAL MODELS

266

the form of the contour, the frameworks may be frameworks with parallel flanges

(Fig.4.38,a) or frameworks with polygonal flanges (Fig.4.38,b).

Among the simple articulated systems, we mention: rectangular system trusses

(Fig.4.38,a), trapezoidal system trusses (Fig.4.38,b), triangular system trusses

(Fig.4.38,c) and

K lattice trusses (Fig.4.38,d). If over a primitive system of bars is

introduced a supplementary system, then one obtains a compound articulated system.

The double rectangular system trusses, the double triangular system trusses or the

trusses with multiple lattices form complex articulated systems.

To determine the efforts in the bars of a framework, one may use various methods of

computation. Thus, in the method of sections (Ritter’s method) a complete section is

made, and the conditions of equilibrium of one of the two parts are put. Only three

unknowns may appear, because one can write only three equations of equilibrium; if the

reactions have been previously obtained, then the unknowns may be only efforts in the

sectioned bars, so that these ones cannot be more than three. We notice that these bars

must not be all concurrent or parallel; in such a case, the three equations are no more

linearly independent.

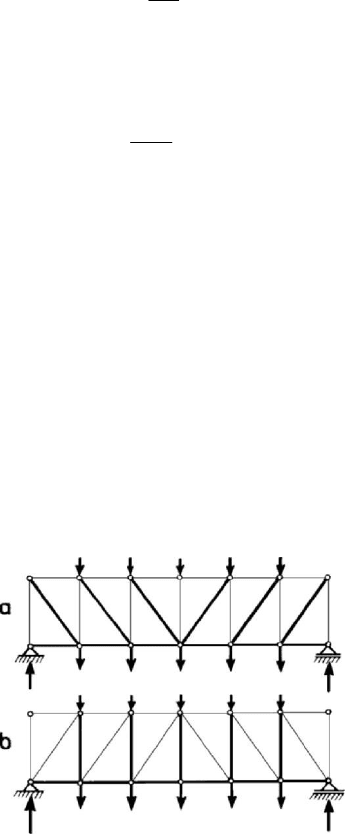

Figure 4.39. Equilibrium of a framework with parallel flanges.

Let be a framework with parallel flanges (Fig.4.39), of height

h

, acted upon by

vertical concentrated forces at the nodes. Because the truss is simply supported, the

reactions can be obtained from its global equilibrium, as in the case of a usual straight

bar. Let thus be a section I-I; we replace the sectioned bars (3-5, 2-4 and 3-4) by the

corresponding efforts (

35

S

−

,

24

I

−

and

34

D

−

), with a positive sign. We consider the

equilibrium of the left part of the truss. The equation of moment with respect to the

node 3 leads to

3

24

M

I

h

−

=

,

(4.2.48)

where

3

M is the moment of the given and constraint forces acting upon the left part of

the bar with respect to the node 3 (positive if the corresponding couple leads to a

clockwise rotation in the plane); analogously, the equation of moment about the node 4

allows to write

Statics

267

4

35

M

S

h

−

=− ,

(4.2.48')

where

4

M

has a similar signification. The equation of projection on the normal

common to the two parallel flanges yields

1

34

sin

T

D

ϕ

−

= ,

(4.2.48'')

where

1

T is the projection on the considered direction of all the given and constraint

forces at the left of section I-I, while

ϕ is the angle formed by the diagonal with one of

the flanges. We notice that

M and T have the significance of a bending moment and

of a shearing force in a straight bar, respectively, their sign being analogously

established. In the case of a section II-II, the equation of projection on the normal

common to the parallel flanges leads to

II45

VT

−

=

, (4.2.49)

where

II

T has an analogous significance. One obtains thus the efforts in all the bars of

the framework. Only for the vertical member 6-7 one must make a section of the form

III-III (we isolate the node 7), wherefrom

67 7

VP

−

=

−

. (4.2.50)

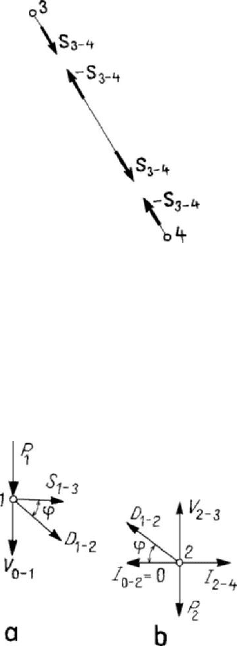

Figure 4.40. Framework with tensioned (a) or compressed (b) diagonals.

Such a bar for which the effort depends only on a local load, being independent of the

form of the beam and of its loading, is called a supplementary bar.

As we can see, it follows that in the bars of the superior flanges and in the vertical

beams appear only efforts of compression, while in the bars of the inferior flanges and

in the diagonals we have efforts of tension. The compressed bars are traced by thin

lines, while the tensioned ones are traced by thick lines (Fig.4.40,a). If the diagonals

of each pane would be ascendent towards the middle of the truss (instead to be

MECHANICAL SYSTEMS, CLASSICAL MODELS

268

descendent, as in the previous case), then they would be compressed and the vertical

members tensioned, but the bars of the flanges would have efforts of the same sign as

above. These results are rendered by the same graphical convention in Fig.4.40,b; we

notice that the efforts in the superior flanges of the panes and in the end vertical

members vanish. Indeed, these affirmations are justified because between the efforts in

the bars and the forces acting at the nodes take place relations of the type of those

between the internal forces (see, e.g., the nodes 3 and 4 and the bar 3-4, Fig.4.41).

This method of computation may be applied analogously in the case of a truss with

polygonal flanges; we mention that it can be used in a graphical variant too.

Another method of computation often used is the method of isolation of nodes, which

is – in fact – a particular case of the method of sections; in the frame of this method,

each node is isolated, by sectioning the bars which start form this one and by replacing

them by the corresponding efforts. One obtains thus, in each node, a system

Figure 4.41. Efforts in the members of a framework.

of forces which must be in equilibrium. Two equations can be thus written for each

node; this method of computation is convenient if we can solve these equations for each

node separately. We start from a node where intervene only two unknowns, passing

than to neighbouring nodes where intervene only two unknowns too. For instance, in

the case of the truss with parallel flanges considered in Fig.4.39 one starts from the

Figure 4.42. Method of separation of nodes.

node

O

; previously, the reactions have been determined by a global equilibrium (the

method of rigidity). One obtains thus

02

0I

−

=

and

0

01

VV

−

=

−

(Fig.4.39). Then, one

passes – successively – to the equilibrium of the node 1 (Fig.4.42,a), to the equilibrium

Statics

269

of node 2 (Fig.4.42,b) a.s.o. Sometimes, it is useful to combine the method of isolation

of nodes with the method of sections, as in the case of

K lattice trusses (Fig.4.38,d).

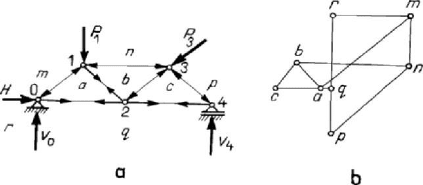

Figure 4.43. A triangular truss (a) and the corresponding Maxwell-Cremona draught (b).

The method of isolation of nodes is graphically concretized in the Maxwell-Cremona

draught. Let be the truss 0-1-2-3-4, acted upon by the forces

1

P and

3

P (Fig.4.43,a).

We use Bow’s notation, denoting by m, n, p, q, r the zones in which is divided the

exterior of the framework by the given and constraint forces which act upon it; as well,

we denote by a, b, c the zones in the interior of the truss, separated by bars or by the

corresponding efforts. Each given and external force and each effort will be expressed

in the form

N

αβ

, where the indices ,αβ correspond to the zones m, n, p, q, r, a, b, c

on one and the other part of the respective force. First of all, the polygon of given and

constraint forces, which is a closed one, is drawn. Then, one constructs the polygon of

forces for the equilibrium of each node, taking the forces clockwise around the node, in

the order in which they are met. We notice that to each node of the truss (Fig.4.43,a)

there corresponds a closed polygon in the Maxwell-Cremona draught (Fig.4.43,b),

while to each closed polygon of the truss (the polygons at the exterior of the truss are

closed at infinity) there corresponds a point of intersection of the respective sides on the

draught. Such figures are called reciprocal, while the method is called the method of

reciprocal polygons too. Denoting the intervals on the framework, the signs of the

efforts are determined on the figure, taking into account the direction along a polygon

according the clockwise direction around the corresponding node on the framework; if

the force stretches the node, then the effort is of tension (as in Fig.4.41), otherwise, it is

of compression.

The compound structures may be studied analogously, by the methods indicated

above. In the case of complex structures in which there is not one node with only two

unknowns and not one section cutting only three non-concurrent members or for which

one cannot make a decomposition in simple structures to which the application of these

methods be possible, one must make – in general – a study of the whole framework;

such a study involves the solution of a system of

2n linear algebraic equations for the

n nodes of the truss. But, from case to case, one can apply the method of bars

replacing of Henneberg or the two sections method of S.A. Tsaplin.

The spatial articulated systems are also systems of bars linked by hinges so as to

form a non-deformable structure from a geometric point of view, and where the loads

are applied at the nodes; but the members of the truss are no more coplanar.

The simple articulated systems are those obtained by joining tetrahedra formed by

bars; such a tetrahedron has six bars, corresponding to its sides. By complete induction,

one can show that