Schenken Suzanne O’Dea. From Suffrage to the Senate: An Encyclopedia of American Women in Politics (2 Volumes)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

But that’s all going to change. If you ever get a chance, go down to Parlier.

Chicanos turned around the whole city council there. So when the farm workers

set up a picket line in Parlier, the cops wouldn’t even come near us. There’s a

whole change in the picture because those people exercised their political power,

they participated in democracy.

The worst thing that I see is guys who say, “Man, they don’t have no Chi-

canos up there and they’re not doing this or that for Chicanos.” But the “vatos”

are just criticizing and they’re not in there working to make sure that it happens.

We criticize and separate ourselves from the process. We’ve got to jump right in

there with both feet.

Most of the people doing the work for us are gabachillos [nice Anglos].

When we get Chicano volunteers it’s really great. But the Chicanos who come

down to work with the farm workers have some hang-ups, especially the guys that

come out of college. “En primer lugar, le tienen miedo a la gente” [in the first

place, they are afraid of the people]. Unless they come out of the farm worker

communities themselves, they get down there and they’re afraid of the people. I

don’t know why it happens, but they’re afraid to deal with them. But you have to

deal with them like people, not like they were saints. The Chicano guys who come

down here have a very tough time adjusting. They don’t want to relate to the poor

farm workers anymore. They tried so hard to get away from that scene and they

don’t want to go back to it.

We have a lot of wonderful people working with us. But we need a lot more

because we have a whole country to organize. If the people can learn to organize

within the union, they can go back to their own communities and organize. We

have to organize La Raza in East Los Angeles. We have to do it. We have one thou-

sand farm workers in there right now organizing for the boycott. In the future, we

would very much like to organize around an issue that isn’t a farm worker issue.

But we just can’t because we just don’t have the time.

Maybe some day we can finish organizing the farm workers, but it’s going

so slow because of all the fights we have to get into. We’ll have a better idea of

where we’re at once the lettuce boycott is won. See, there’s about two hundred to

three hundred growers involved in the lettuce boycott. The same growers who

grow lettuce grow vegetables like artichokes and broccoli. So if we get that out of

the way we’ll have about one third of the state of California organized. That’s a

big chunk. From there, hopefully, we can move on to the citrus and get that out

of the way. We have to move into other states, like we did into Arizona.

It would seem that with the Republicans in for another four years, though,

we’ll have a lot of obstacles. Their strategy was to get Chicanos into the Republi-

can party. But we refuse to meet with, for example, Henry Ramírez [chairman of

the President’s Cabinet Committee on Opportunities for the Spanish-Speaking].

He went around and said a lot of terrible things about us at the campuses back

east. He thought that we didn’t have any friends back there. But we do, and they

wrote us back and told us that he was saying that the farm workers didn’t want

the union, that César was a Communist, and just a lot of stupid things. This is

supposed to be a responsible man.

Then there is Philip Sánchez [National director of the Office of Economic

Opportunity]. I went to his home in Fresno once when a labor contractor shot this

farm worker. I was trying to get the D.A.’s office to file a complaint against the la-

Documents 829

bor contractor. So I went to see Philip Sánchez to see if he could help me. But the

guy wouldn’t help me. Later when the growers got this group of labor contractors

together to form a company union against us, Sánchez went and spoke to their

meeting. It came out in the paper that he was supporting their organization. As far

as I’m concerned, Philip Sánchez has already come out against the farm workers.

It’s really funny. Some of the Puerto Riqueños who are in the President’s

Committee for the Spanish-speaking, man, they tell the administration what the

Puerto Ricans need. “Se pelean con ellos” [They fight with them]. But the Chi-

canos don’t. They’re caught. They just become captives.

I spoke to a lot of the guys in Washington who were in these different

poverty programs. Some of the Chicanos had been dropped in their positions of

leadership. They put [other] guys over [the Chicanos]....they put watchdogs on

them to make sure that they don’t do anything that really helps the farm workers.

The guys are really afraid because there’s just a few jobs and they can be easily re-

placed. They’re worse off than the farm workers, you see. The farm workers at

least have the will to fight. They’re not afraid to go out on strike and lose their

jobs. But the guy who has a nice fat job and is afraid to go out and fight, well,

they’ve made him a worse slave than the farm worker.

An ex-priest told me one time that César should really be afraid somebody

might write a book to expose him. I said, “Don’t even kid yourself that César is

afraid of anybody because he’s not. The only ones who might scare him are God

and his wife, Helen. But besides them he’s not afraid of anyone.”

He’s got so much damn courage,“y así come es él” [and he is as he is]. That’s

the way the farm workers are. They have this incredible strength. I feel like a big

phony because I’m over here talking and they’re out there in the streets right now,

walking around in the rain getting people to vote. “Son tan dispuestos a sufrir”

[They are so ready to suffer], and they take whatever they have to take because

they have no escape hatch.

Being poor and not having anything just gives an incredible strength to peo-

ple. The farm workers seem to be able to see around the corner, and César has

that quality because he comes out of that environment. César’s family were mi-

grant workers. It was kind of the reverse of mine because they started with a farm

in Yuma but lost it during the depression. They had to migrate all over the state

to earn a living, and they had some really horrible times, worse than anything we

ever suffered. So there was a lot more hardship in his background. But his family

had a lot of luck. His mom and dad were really together all the time.

César always teases me. He says I’m a liberal. When he wants to get me mad

he says,“You’re not a Mexican,” because he says I have a lot of liberal hang-ups in

my head. And I know it’s true. I am a logical person. I went to school and you

learn that you have to weigh both sides and look at things objectively. But the

farm workers know that wrong is wrong. They know that there’s evil in the world

and that you have to fight evil. They call it like it is.

When I first went to work in the fields after I had met Fred Ross, the first

thing that happened was that I was propositioned by a farmer. People who work

in the fields have to take this every day of their lives, but I didn’t know how to

handle it. So I wondered if I should be there at all, because I had gone to college.

I had gone to college to get out of hard labor. Then all of a sudden there I was do-

ing it again.

830 Documents

I feel glad now that I was able to do it. It’s good my kids have done field

work now, too, because they understand what it all means. I feel very humble with

the farm workers. I think I’ve learned more from them than they would ever learn

from me.

From La Voz del Pueblo (November–December 1972). Reprinted by permission.

Sexual Harassment: The Nature of the Beast, Anita Hill, 1992

The response to my Senate Judiciary Committee testimony has been at once

heartwarming and heart-wrenching. In learning that I am not alone in experi-

encing harassment, I am also learning that there are far too many women who

have experienced a range of inexcusable and illegal activities—from sexist jokes

to sexual assault—on the job.

“The Nature of the Beast” describes the existence of sexual harassment, which

is alive and well. A harmful, dangerous thing that can confront a woman at any time.

What we know about harassment, sizing up the beast:

Sexual harassment is pervasive . . .

1. It occurs today at an alarming rate. Statistics show that anywhere from

42% to 90% of women will experience some form of harassment during their

employed lives.

2. It has been occurring for years.

3. Harassment crosses lines of race and class.

We know that harassment all too often goes unreported for a variety of

reasons...

1. Unwillingness (for good reason) to deal with the expected consequences.

2. Self-blame.

3. Threats or blackmail by co-workers or employers.

4. What it boils down to in many cases is a sense of powerlessness that we

experience in the workplace, and our acceptance of a certain level of inability to

control our careers and professional destinies.

That harassment is treated like a woman’s “dirty secret” is well known. We also

know what happens when we “tell.” We know that when harassment is reported the

common reaction is disbelief or worse . . .

1. Women who “tell” lose their jobs.

2. Women who “tell” become emotionally wasted.

3. Women who “tell” are not always supported by other women.

What we are learning about harassment requires recognizing this beast

when we encounter it, and more. It requires looking the beast in the eye.

We are learning painfully that simply having laws against harassment on the

books is not enough. The law, as it was conceived, was to provide a shield of pro-

tection for us.Yet the shield is failing us: many fear reporting, others feel it would do

no good. The result is that less than 5% of women victims file claims of harassment.

As we are learning, enforcing the law alone won’t terminate the problem.

What we are seeking is equality of treatment in the workplace. Equality requires

an expansion of our attitudes toward workers. Sexual harassment denies our

treatment as equals and replaces it with treatment of women as objects of ego or

power gratification.

We are learning that women are angry. The reasons for the anger are various

and perhaps all too obvious...

Documents 831

1. We are angry because this awful thing called harassment exists in terribly

harsh, ugly, demeaning, and even debilitating ways.

2. We are angry because for a brief moment we believed that if the law al-

lowed for women to be hired in the workplace, and if we worked hard for our ed-

ucations and on the job, equality would be achieved. We believed we would be re-

spected as equals. Now we are realizing this is not true. The reality is that this

powerful beast is used to perpetuate a sense of inequality, to keep women in their

place, notwithstanding our increasing presence in the workplace.

What we have yet to explore about harassment is vast. It is what will enable

us to slay the beast.

How do we capture the rage and turn it into positive energy? Through the

power of women working together, whether it be in the political arena, or in the

context of a lawsuit, or in community service. This issue goes well beyond parti-

san politics. Making the workplace a safer, more productive place for ourselves

and our daughters should be on the agenda for each of us. It is something we can

do for ourselves. It is a tribute, as well, to our mothers—and indeed a contribu-

tion we can make to the entire population.

I wish that I could take each of you on the journey that I’ve been on during

all these weeks since the hearing. I wish that every one of you could experience

the heartache and triumphs of each of those who have shared with me their ex-

periences. I leave you with but a brief glimpse of what I’ve seen. I hope it is

enough to encourage you to begin—or continue and persist with—your own

exploration.

Reprinted by permission of the Southern California Law Review, 65 S. Cal L

Rev. 1445–1449 (1992).

Statement on Equal Pay Day, Linda Chavez-Thompson, 1998

Last September, the AFL-CIO—which with 5 1/2 million women members is the

largest organization of working women in the country—asked working women

in every kind of job—in every part of the country—to tell us about the biggest

problem they face at work.

Ninety-nine percent said a top concern is equal pay.

And most women told us that despite the economic good times, it is just as

hard now as it was five years ago to make ends meet....or it’s become even

harder.

The truth is that working women need and deserve equal pay.

The wage gap between women and men is huge.

If it is not changed, the average 25-year-old working woman can expect to

lose $523,000 over the course of her work life.

That’s enough to make a world of difference for most working families.

It can mean decent health care . . . a college education for the kids...a se-

cure retirement...and simply being able to pay the monthly bills on time.

That is what the wage gap now takes from working women.

It’s the price of unequal pay.

Patricia Hoersten knows what that’s about.

Pat served lunch and dinner at a diner in Lima, Ohio. She got paid half of

what the male servers got paid—because her supervisor thought she only needed

extra money, not money to live on.

832 Documents

The tragedy is that there are millions of women who are experiencing the

very same injustice.

Is this a women’s issue?

It is—but it’s also a family issue, because women’s wages are essential to

their families.

Most working women contribute half or more of their household’s income.

So when working women lose out, working families lose out.

The good news is that working women are joining together to fight for

equal pay.

I’ve been able to hear from many of them.

One is Maria Olivas. She’s a clerical worker at Columbia University.

Maria worked with her union to make sure that her employer disclosed how

much it paid men and women for the same job. They found out that men were

paid $1,500 more than women for the same job. After a long struggle, they were

able to win equal pay.

There are lots more like her.

Grocery store clerks at Publix Supermarkets won $80 million in back pay

because they were not getting equal pay and promotions.

But no woman should have to fight by herself for equal pay.

That’s why the AFL-CIO has launched a nationwide grassroots campaign to

fight for women’s wages.

That’s why the union movement is making equal pay one of the main goals

of our 1998 Agenda for Working Families.

And that’s why the AFL-CIO applauds, supports, and will work to enact the

legislation being introduced by Senator Tom Daschle and Representative Rosa

DeLauro.

This legislation will give women an important weapon to battle wage dis-

crimination and to help close the wage gap. It’s about time.

Reprinted by permission of the AFL-CIO.

Documents 833

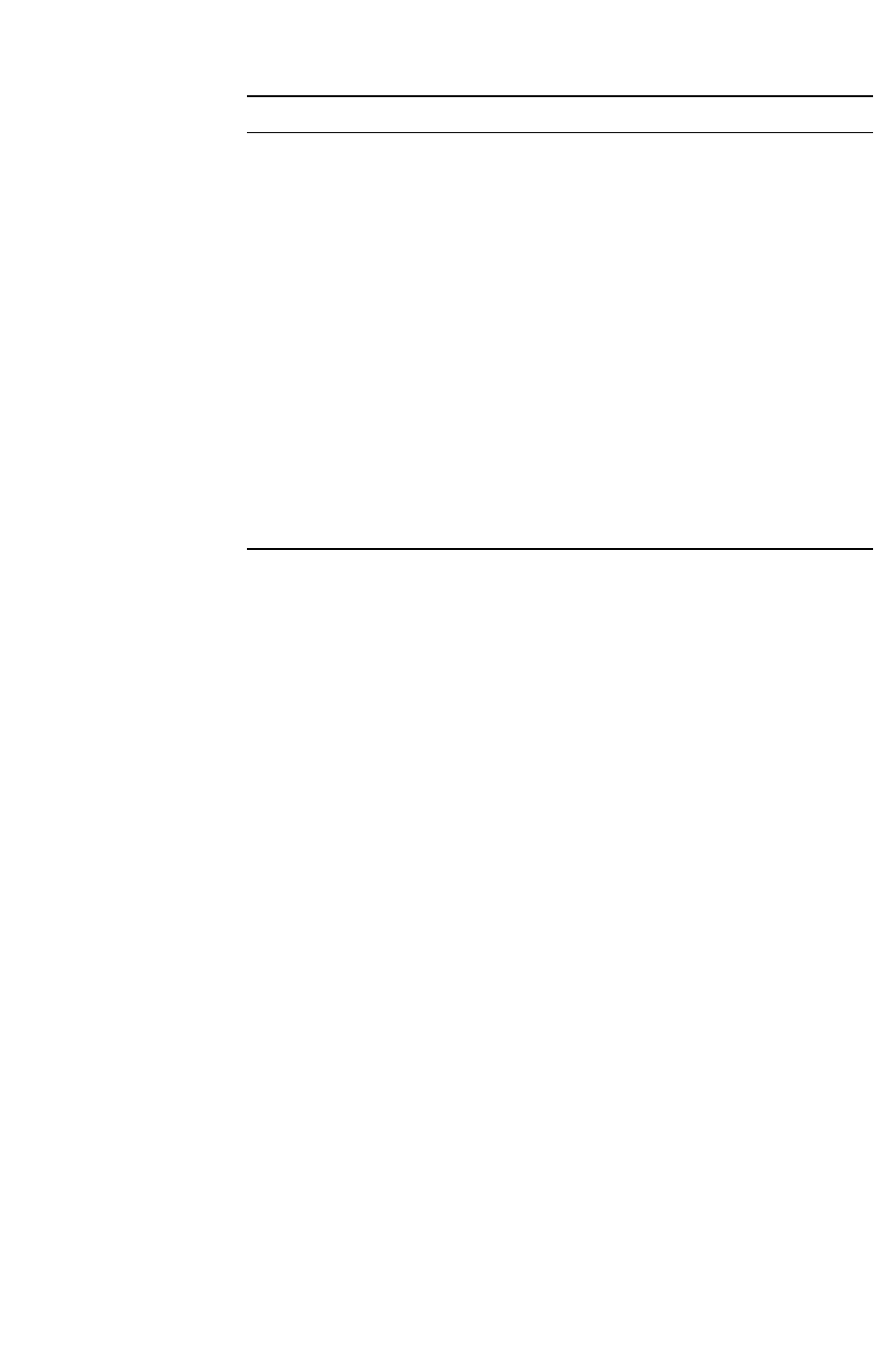

Table A.1 Number of Women in Congress

A

Congress House of Representatives Senate

65th (1917–1919) 1 (0D, 1R) 0 (0D, 0R)

66th (1919–1921) 0 (0D, 0R) 0 (0D, 0R)

67th (1921–1923) 3 (0D, 3R) 1 (1D, 0R)

68th (1923–1925) 1 (0D, 1R) 0 (0D, 0R)

69th (1925–1927) 3 (1D, 2R) 0 (0D, 0R)

70th (1927–1929) 5 (2D, 3R) 0 (0D, 0R)

71st (1929–1931) 9 (5D, 4R) 0 (0D, 0R)

72nd (1931–1933) 7 (5D, 2R) 1 (1D, 0R)

73rd (1933–1935) 7 (4D, 3R) 1 (1D, 0R)

74th (1935–1937) 6 (4D, 2R) 2 (2D, 0R)

75th (1937–1939) 6 (5D, 1R) 2 (1D, 1R)

76th (1939–1941) 8 (4D, 4R) 1 (1D, 0R)

77th (1941–1943) 9 (4D, 5R) 1 (1D, 0R)

78th (1943–1945) 8 (2D, 6R) 1 (1D, 0R)

79th (1945–1947) 11 (6D, 5R) 0 (0D, 0R)

80th (1947–1949) 7 (3D, 4R) 1 (0D, 1R)

81st (1949–1951) 9 (5D, 4R) 1 (0D, 1R)

82nd (1951–1953) 10 (4D, 6R) 1 (0D, 1R)

83rd (1953–1955) 11 (5D, 6R) 2 (OD, 2R)

84th (1955–1957) 16 (10D, 6R) 1 (0D, 1R)

85th (1957–1959) 15 (9D, 6R) 1 (0D, 1R)

86th (1959–1961) 17 (9D, 8R) 2 (1D, 1R)

87th (1961–1963) 18 (11D, 7R) 2 (1D, 1R)

88th (1963–1965) 12 (6D, 6R) 2 (1D, 1R)

89th (1965–1967) 11 (7D, 4R) 2 (1D, 1R)

90th (1967–1969) 11 (6D, 5R) 1 (0D, 1R)

835

Appendix 2: Facts and Statistics

Table A.1 Number of Women in Congress (continued)

Congress House of Representatives Senate

91st (1969–1971) 10 (6D, 4R) 1 (0D, 1R)

92nd (1971–1973) 13 (10D, 3R) 2 (1D, 1R)

93rd (1973–1975) 16 (14D, 2R) 0 (0D, 0R)

94th (1975–1977) 19 (14D, 5R) 0 (0D, 0R)

95th (1977–1979) 18 (13D, 5R) 2 (2D, 0R)

96th (1979–1981) 16 (11D, 5R) 1 (0D, 1R)

97th (1981–1983) 21 (11D, 10R) 2 (0D, 2R)

98th (1983–1985) 22 (13D, 9R) 2 (0D, 2R)

99th (1985–1987) 23 (12D, 11R) 2 (0D, 2R)

100th (1987–1989) 23 (12D, 11R) 2 (1D, 1R)

101st (1989–1991) 29 (16D, 13R) 2 (1D, 1R)

102nd (1991–1993) 28 (19D, 9R) 4 (3D, 1R)

103rd (1993–1995) 47 (35D, 12R) 7 (5D, 2R)

104th (1995–1997) 47 (30D, 17R) 8 (5D, 3R)

105th (1997–1999) 51 (35D, 16R) 9 (6D, 3R)

106th (1999–2001) 56 (39D, 17R) 9 (6D, 3R)

Note: A. This table shows the maximum number of women serving at one time. It does not

include delegates from territories or Washington, D.C. Some of the women filled unex-

pired terms and others were not sworn into office.

Source: Center for the American Woman and Politics, Eagleton Institute of Politics, Rut-

gers University.

836 Appendix: Facts and Statistics

Table A.2 Women of Color in Congress

Years

Congressmember Heritage Served

Patsy Takemoto Mink (D-HI) Japanese American 1965–

Shirley Chisholm (D-NY) African American 1969–1983

Yvonne Burke (D-CA) African American 1973–1979

Barbara Jordan (D-TX) African American 1973–1979

Cardiss Collins (D-IL) African American 1973–1997

Katie Hall (D-IN) African American 1982–1985

Patricia F. Saiki (D-HI) Japanese American 1987–1991

Ileana Ros-Lehtinen (R-FL) Cuban American 1989–

Eleanor Holmes Norton (D-DC) African American 1991–

Barbara-Rose Collins (D-MI) African American 1991–1997

Maxine Waters (D-CA) African American 1991–

Carol Moseley Braun (D-IL) African American 1993–1999

Corrine Brown (D-FL) African American 1993–

Carrie Meek (D-FL) African American 1993–

Cynthia McKinney (D-GA) African American 1993–

Eva Clayton (D-NC) African American 1993–

Eddie Bernice Johnson (D-TX) African American 1993–

Lucille Roybal-Allard (D-CA) Mexican American 1993–

Nydia Velasquez (D-NY) Puerto Rican American 1993–

Sheila Jackson Lee (D-TX) African American 1995–

Juanita Millender-McDonald (D-CA) African American 1996–

Julia Carson (D-IN) African American 1997–

Donna Christian-Green (D-VI) African American 1997–

Carolyn C. Kilpatrick (D-MI) African American 1997–

Loretta Sanchez (D-CA) Mexican American 1997–

Barbara Lee (D-CA) African American 1998–

Stephanie Tubbs-Jones (D-OH) African American 1998–

Grace Napolitano (D-CA) Mexican American 1998–

Note: Eleanor Holmes Norton and Donna Christian-Green are delegates from the District

of Columbia and the Virgin Islands, respectively.

Source: Martin, Almanac of Women and Minorities in American Politics (1999) and Center

for the American Woman and Politics, Eagleton Institute of Politics, Rutgers University.

Appendix: Facts and Statistics 837

Table A.3 Women in Congressional Leadership Roles

U.S. Senate

106th Congress 1999–2001

Senator Barbara Boxer (D-CA), Deputy Minority Whip

Senator Kay Bailey Hutchison (R-TX), Senate Deputy Majority Whip

Senator Barbara Mikulski (D-MD), Secretary of the Senate Democratic

Conference

Senator Olympia Snowe (R-ME), Secretary of the Senate Republican Conference

105th Congress 1997–1999

Senator Kay Bailey Hutchison (R-TX), Senate Deputy Majority Whip

Senator Barbara Mikulski (D-MD), Secretary of the Senate Democratic

Conference

Senator Olympia Snowe (R-ME), Secretary of the Senate Republican

Conference

104th Congress 1995–1997

Senator Kay Bailey Hutchison (R-TX), Senate Deputy Whip

Senator Barbara Mikulski (D-MD), Secretary of the Senate Democratic

Conference

103rd Congress 1993–1995

Senator Barbara Boxer (D-CA), Deputy Majority Whip

Senator Barbara Mikulski (D-MD), Assistant Senate Democratic Floor Leader

U.S. House of Representatives

106th Congress 1999–2001

Representative Barbara Cubin (R-WY), House Deputy Majority Whip

Representative Diana DeGette (D-CO), House Deputy Minority Whip

Representative Rosa DeLauro (D-CT), Assistant to the Democratic Leader

Representative Tillie Fowler (R-FL), Vice Chairman of the House Republican

Conference

Representative Kay Granger (R-TX), Assistant Majority Whip

Representative Eddie Bernice Johnson (D-TX), Democratic Deputy Whip

Representative Nita Lowey (D-NY), Minority Whip At-Large

Representative Deborah Pryce (R-OH), House Republican Conference Secretary

Representative Louise Slaughter (D-NY), Minority Whip-At-Large

Representative Lynn Woolsey (D-CA), House Deputy Minority Whip

105th Congress 1997–1999

Representative Eva Clayton (D-NC), Co-chair of the House Democratic Policy

Committee

Representative Barbara Cubin (R-WY), House Deputy Majority Whip

Representative Rosa DeLauro (D-CT), House Chief Deputy Minority Whip

Representative Jennifer Dunn (R-WA), Vice Chair of the House Republican

Conference

Representative Tillie Fowler (R-FL), House Deputy Majority Whip

Representative Kay Granger (R-TX), Assistant Majority Whip

Representative Barbara Kennelly (D-CT), Vice Chair of the Democratic Caucus

Representative Nita Lowey (D-NY), Minority Whip At-Large

Representative Susan Molinari (R-NY), Vice Chair of the House Republican

Conference

838 Appendix: Facts and Statistics