Salby M.L. Fundamentals of Atmospheric Physics

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

520

16

Hydrodynamic Instability

At the lateral walls, v' must vanish, so 0' =const. It suffices to prescribe

0' = 0 y - +L. (16.6.6)

Equations (16.6) define a second-order boundary value problem for the distur-

bance streamfunction ~'(x, t)--one that is homogeneous. Containing no im-

posed forcing, (16.6) describes a system that is self-governing or autonomous.

Nontrivial solutions (i.e., other than q,' -- 0) exist only for certain

eigenfrequen-

cies

that enable boundary conditions to be satisfied. Determined by solving the

homogeneous boundary value problem for a given zonal flow ~(y, z), those

eigenfrequencies are, in general, complex.

Consider solutions of the form

q,' = ~(y,

z)e ik(x-ct),

(16.7)

where 9 and

c - Cr +

ici

can

assume complex values. Substituting (16.7)

transforms (16.6) into

+ --P0 ~zz N2P~ - k2 +/~eXI t-- 0. (16.8.1)

The lower boundary condition (16.6.4)becomes

3~ 3~

(~- c)-- * - 0 z - 0. (16.8.2)

0z 3z

For c real, (16.8) is singular at a critical line where ~ = c. The singularity

disappears if

ci :/: O,

in which case (16.7) contains an exponential modulation

in time. If the flow is stable, wave activity incident on the critical line is

absorbed when dissipation is included (Sec. 14.3). The wave field then decays

exponentially. If the flow is unstable, wave activity can be produced at the

critical line. The wave field can then amplify exponentially.

Multiplying the conjugate of (16.8) by 9 and (16.8) by the conjugate of

and then subtracting yields

"u Oy---g--

ay 2 j + ~---- P0

po Oz kN 2 -~z

(16.9.1)

..10(, 0.)]

PO Oz N2 P o ~z - 2 i c i I -u -

c l

fie "-" 0

and

a~* _ ~, a~ I~] 2 3~ = 0 z - 0. (16.9.2)

3z 3z + 2ici [-u --

c[ 2 o~z

The chain rule allows terms in the first set of square brackets in (16.9.1) to be

expressed

02 XI/'* XI/'* o~2 a~r o ~ [~ o~aIt'* _ XI/'* o~aIr ]

,I, oy----- 7- - 07 = k oy

oy j

16.2 Shear

Instability

521

Terms in the second set of square brackets can be expressed in a similar

manner. Then (16.9.1) can be written

d I~d~*_xi,,O~ 1 10 [f~ (O~* ~,d~)l

3y L 3y 3y + ~ ~ -

Po 7z -~ Po az Oz

(16.10)

- 2ic i l_ ~

_ c[ 213 e -- O.

Integrating over the domain unravels the exterior differentials in (16.10) to

give

xI, 3xI't'* x[t* ~ y=L

- podz

'~Y aY y=-L

+ -~po Ve~--

L o~Z o~Z

z--O

2icifLfo0 ~L

I~I*12

{~._ C[ 2

~edypodz - O.

dy

(16.11)

By (16.6.6), the first integral vanishes. The finite energy condition makes the

upper limit inside the second integral also vanish. Then incorporating (16.9.2)

for the lower limit yields the identity

(16.12)

C i

/3 e ~P01XP'I2

dydz- ~ dy = O,

N 2 I-u cl 2 3z

L 1~- el 2 L -- ~--0

which must be satisfied for ~(y, z) to be a solution of (16.6).

Advanced by Charney and Stern (1962), the preceding identity provides

"necessary conditions" for instability of the zonal-mean flow K(y, z). If c is

complex, (16.7) describes a disturbance whose amplitude varies in time expo-

nentially

eik(x-ct) = ekci t . eik(x-Crt),

with the growth/decay

rate

kc i.

Without loss of generality, k can be considered

positive, so the existence of unstable solutions requires

ci

> 0. Unstable solu-

tions are then possible only if the quantity inside braces in (16.12) vanishes. If

it does not, (16.12) implies

ci

= 0 and solutions to (16.6) are stable.

16.2.2 Barotropic and Baroclinic Instability

Requiring (16.12) to be satisfied with

c i

>

0

provides two alternative criteria

for instability:

522

16 Hydrodynamic Instability

1. If

3-~13z

vanishes at the lower boundary, so does the temperature

gradient by thermal wind balance. Then /3e -

3Q/3y

must reverse

sign somewhere in the interior. Since/3 e isnormally positive, a region

of negative potential vorticity gradient,

oQ/3y

< 0, is identified as an

unstable region of the mean flow.

2. If/3 e > 0 throughout the interior,

3-u/3z

must be positive somewhere

on the lower boundary. By thermal wind balance, this implies the

existence of an equatorward temperature gradient at the surface.

Other combinations are also possible, but these are the ones most relevant

to the atmosphere. Neither represents a "sufficient condition" for instability.

Satisfying criterion (1) or (2) does not ensure the existence of unstable

solutions.

Criterion (1) defines a necessary condition for free-field instability (e.g., in-

stability for which boundaries do not play an essential role). From (16.6.3), the

mean gradient of potential vorticity can reverse sign through strong horizon-

tal curvature of the mean flow or through strong (density-weighted) vertical

curvature of the mean flow. It is customary to distinguish these contributions

to

eQ/3y.

If the necessary condition for instability is met through horizontal

shear, amplifying disturbances are referred to as

barotropic instability.

If it is

met through vertical shear (which is proportional to the horizontal temper-

ature gradient and the departure from barotropic stratification), amplifying

disturbances are referred to as

baroclinic instability.

Realistic conditions of-

ten lead to criterion (1) being satisfied by both contributions, in which case

amplifying disturbances are combined barotropic-baroclinic instability.

In the absence of rotation, criterion (1) reduces to Rayleigh's (1880) neces-

sary condition for instability of one-dimensional shear flow (Problem 16.12).

Criterion (1) is then equivalent to requiring the mean flow profile to possess

an inflection point. Since /3 is everywhere positive, rotation is stabilizing. It

provides a positive restoring force that inhibits instability and supports stable

wave propagation.

Recall that (16.8) is singular at a critical line K = Cr if

ci

= 0. Exponential

amplification removes the singularity by making

ci

> 0. When boundaries

do not play an essential role, amplifyin__g solutions usually possess a critical

line inside the unstable region where

~Q/~y

< 0 (see, e.g., Dickinson, 1973).

Rather than serving as a localized sink of wave activity, as its does under

conditions of stable wave propagation

(eQ/dy

> 0), the critical line then

functions as a localized source of wave activity. Wave activity flux then diverges

out of the critical line, where it is produced by a conversion from the mean

flow. Alternatively, incident wave activity that encounters the critical line is

"overreflected": More radiates away than is incident on the unstable region.

Criterion (2) describes instability that is produced through the direct in-

volvement of the lower boundary. This criterion applies to baroclinic insta-

bility because it requires a temperature gradient at the surface and hence

16.3 The Eady Problem

523

baroclinic stratification. Since air must move parallel to it, the boundary can

then drive motion across mean isotherms, which transfers heat meridionally

(e.g., in sloping convection). By weakening the temperature gradient, eddy

heat transfer drives the mean thermal structure toward barotropic stratifi-

cation and releases available potential energy (Sec. 15.1), which in turn is

converted to eddy kinetic energy. This situation underlies the development of

extratropical cyclones. Temperature gradients introduced by the nonuniform

distribution of heating make the stratification baroclinic and produce available

potential energy, on which baroclinic instability feeds.

16.3 The Eady Problem

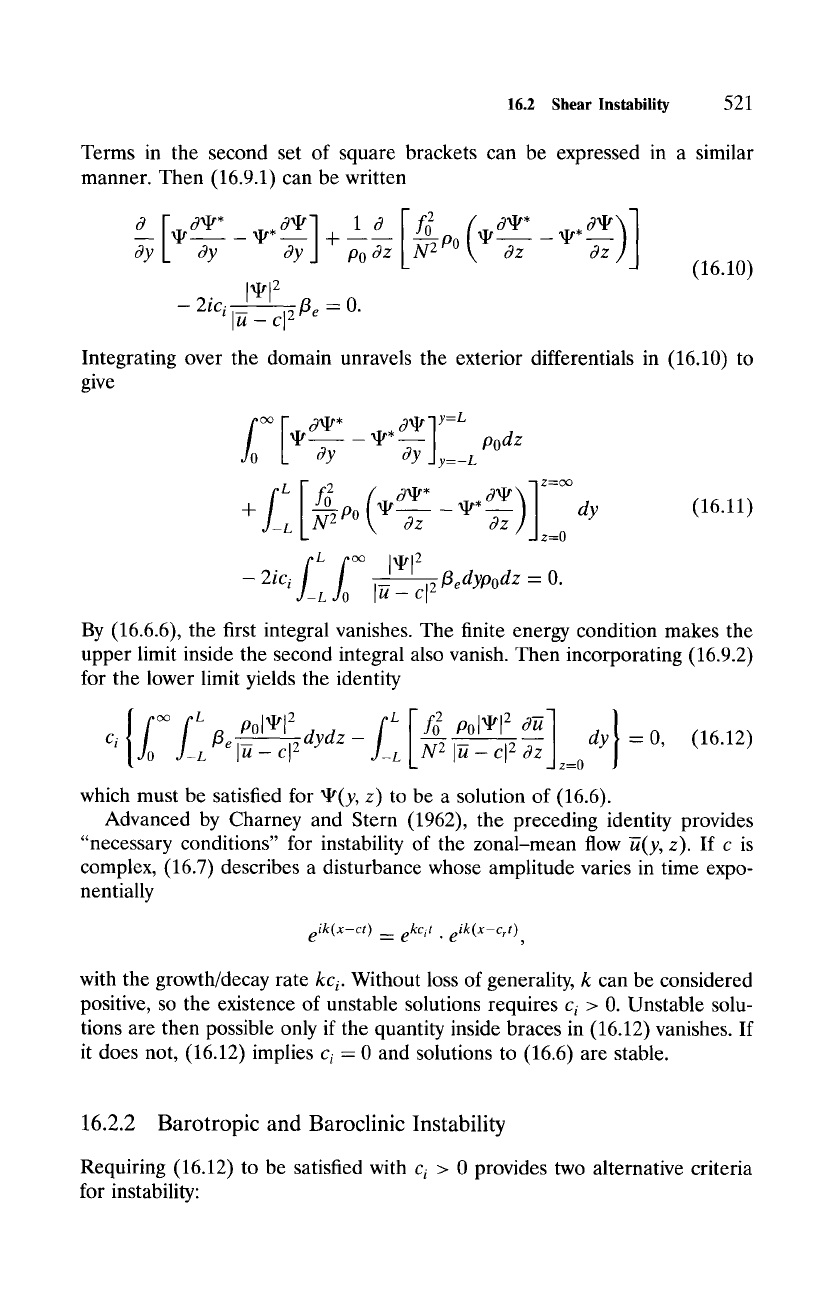

The simplest model of baroclinic instability is that of Eady (1949). Consider

disturbances to a mean flow that is invariant in y, bounded above and below by

rigid walls at z = 0, H on an f plane, and within the Boussinesq approximation

(Sec. 12.5). A uniform meridional temperature gradient is imposed, which, by

thermal wind balance, corresponds to constant vertical shear (Fig. 16.1)

- Az A - const. (16.13)

n

Under these circumstances,

3Q/o~y

vanishes identically in the interior, so in-

stability can follow solely from the temperature gradient along the boundaries.

Disturbances to this system are governed by the perturbation potential

vorticity equation in log-pressure coordinates

D (v2~t'-4- f2 32-----~u)--O

(16.14.1)

Dt N 2 3z 2 '

=Az

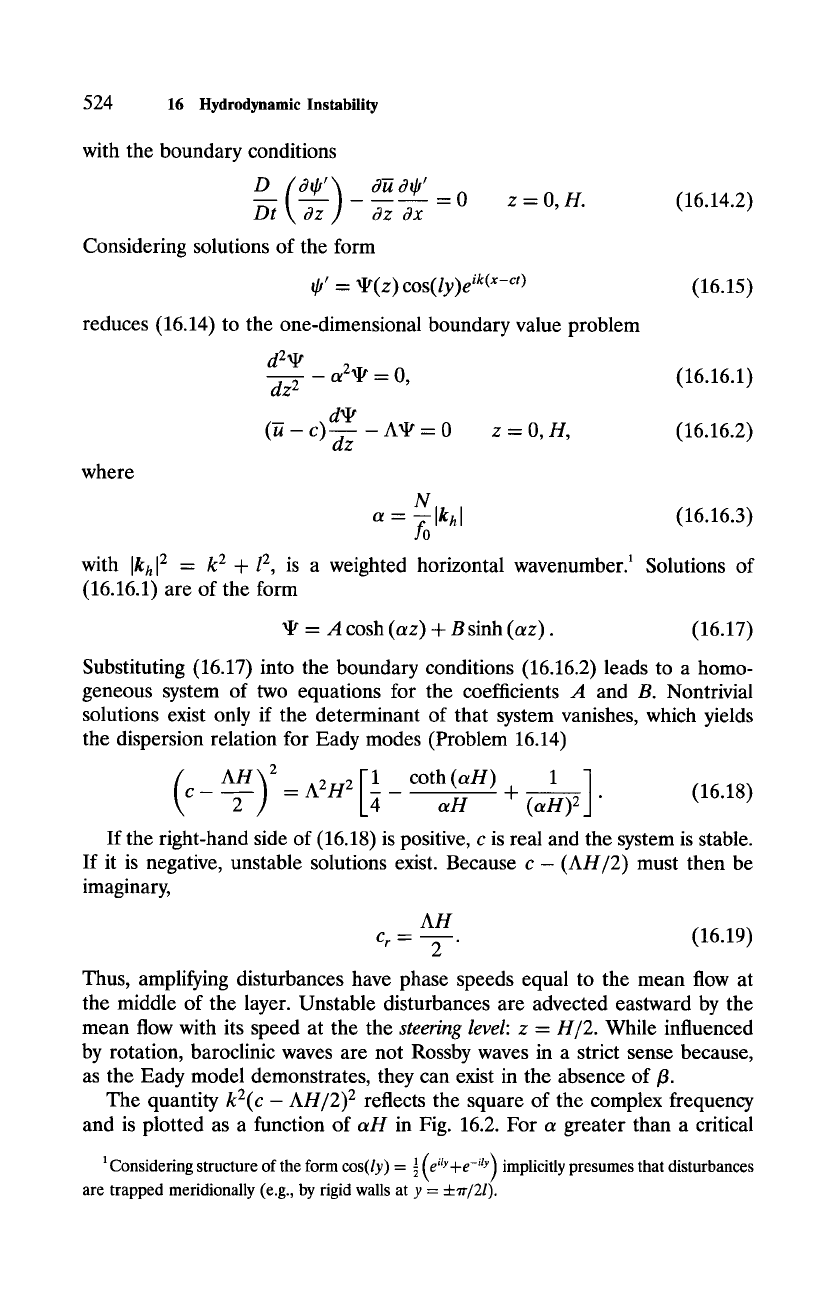

Figure 16.1 Geometry and mean zonal flow in the Eady problem of baroclinic instability.

524 16

Hydrodynamic Instability

with the boundary conditions

D (3q/)

o~3q~'=O

z=O,H.

Dt ~ o~z 3x

Considering solutions of the form

~' = xIt(z) cos(ly)e ik(x-ct)

reduces (16.14) to the one-dimensional boundary value problem

d2~

-- a2a~ t = O,

dz 2

d~

(-~ - c)--~z - A ~ - 0 z = O, H,

where

(16.14.2)

(16:15)

(16.16.1)

(16.16.2)

N

a- ~lkhl

(16.16.3)

with [kh] 2

= k2-+ -/2,

is a weighted horizontal wavenumber. 1 Solutions of

(16.16.1) are of the form

= A cosh

(az) + B

sinh

(az).

(16.17)

Substituting (16.17) into the boundary conditions (16.16.2) leads to a homo-

geneous system of two equations for the coefficients A and B. Nontrivial

solutions exist only if the determinant of that system vanishes, which yields

the dispersion relation for Eady modes (Problem 16.14)

c = A2H2 coth

(all) 1

aH + (all) 2 . (16.18)

If the right-hand side of (16.18) is positive, c is real and the system is stable.

If it is negative, unstable solutions exist. Because c- (AH/2) must then be

imaginary,

AH

Cr

= --~-. (16.19)

Thus, amplifying disturbances have phase speeds equal to the mean flow at

the middle of the layer. Unstable disturbances are advected eastward by the

mean flow with its speed at the the

steering level: z = HI2.

While influenced

by rotation, baroclinic waves are not Rossby waves in a strict sense because,

as the Eady model demonstrates, they can exist in the absence of/3.

The quantity

k2(c-

AH/2) 2 reflects the square of the complex frequency

and is plotted as a function of aH in Fig. 16.2. For a greater than a critical

1( )

1Considering structure of the form cos(/y) = 5

eily+e -ily

implicitly presumes that disturbances

are trapped meridionally (e.g., by rigid walls at y =

•

16.3 The Eady Problem

525

1.0

0.8

0.6

tat)

v

o

~:~ 0.4

T--

X

G

6 o.2

0.0

-0.2

-0.4

0 .2

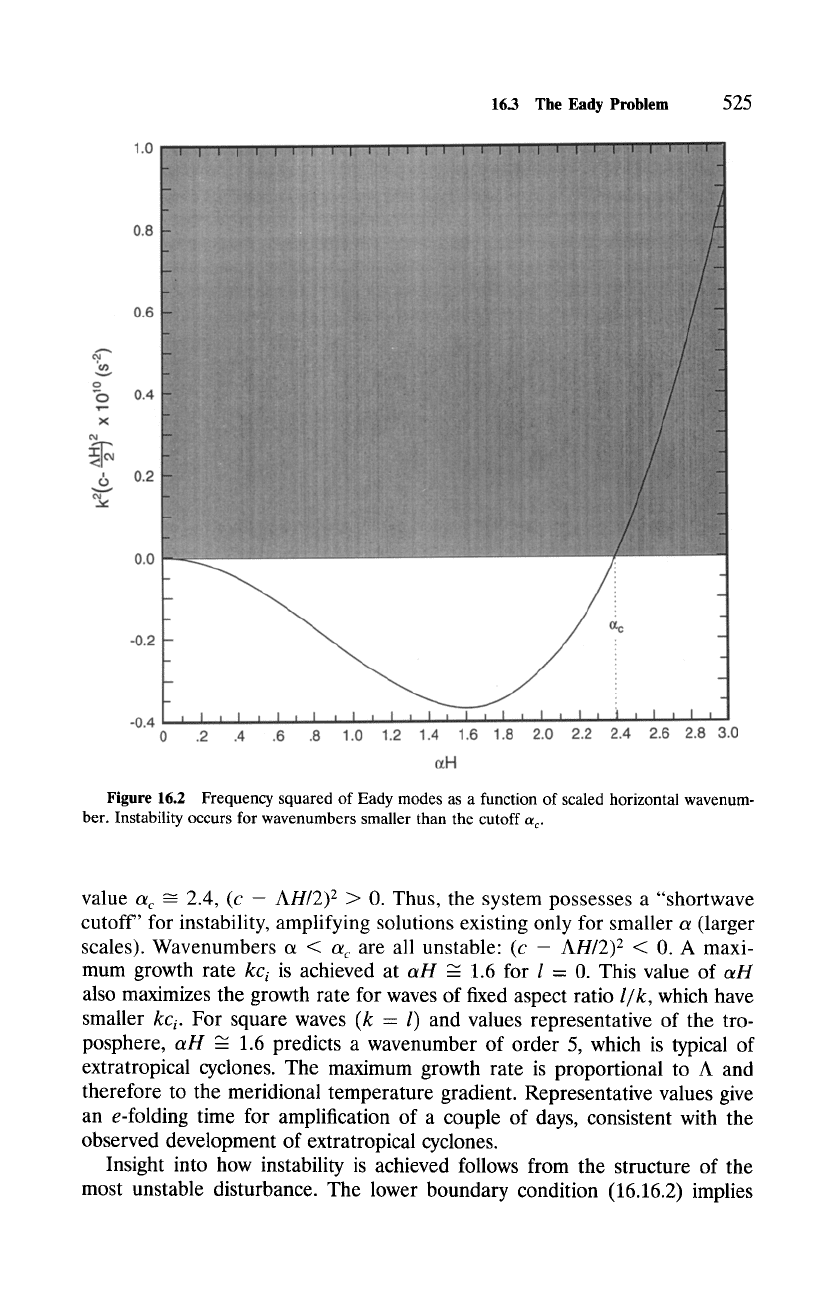

Figure 16.2

ber. Instability occurs for wavenumbers smaller than the cutoff c~ c.

~c

.4 .6 .8 1.0 1.2 1.4 1.6 1.8 2.0 2.2 2.4 2.6 2.8 3.0

(zH

Frequency squared of Eady modes as a function of scaled horizontal wavenum-

value ac ~ 2.4, (c - AH/2) 2 > 0. Thus, the system possesses a "shortwave

cutoff' for instability, amplifying solutions existing only for smaller a (larger

scales). Wavenumbers oL < a~ are all unstable: (c - AH/2) 2 < 0. A maxi-

mum growth

rate

kc i

is achieved at

aH ~

1.6 for l - 0. This value of

aH

also maximizes the growth rate for waves of fixed aspect ratio

l/k,

which have

smaller

kci.

For square waves (k = l) and values representative of the tro-

posphere,

aH ~-

1.6 predicts a wavenumber of order 5, which is typical of

extratropical cyclones. The maximum growth rate is proportional to A and

therefore to the meridional temperature gradient. Representative values give

an e-folding time for amplification of a couple of days, consistent with the

observed development of extratropical cyclones.

Insight into how instability is achieved follows from the structure of the

most unstable disturbance. The lower boundary condition (16.16.2) implies

526

16

Hydrodynamic Instability

the following relationship between the coefficients in (16.17):

B A

= (16.20)

A c~c'

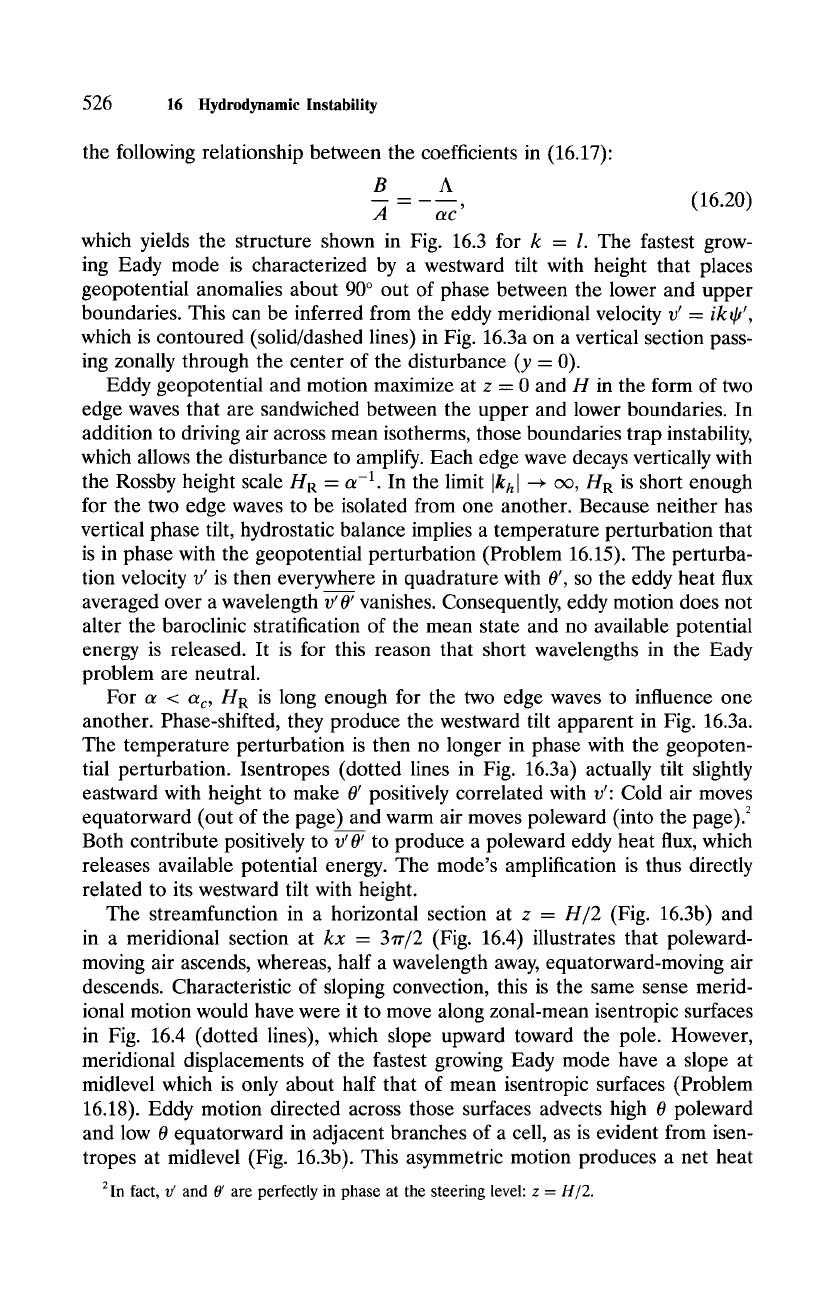

which yields the structure shown in Fig. 16.3 for k - l. The fastest grow-

ing Eady mode is characterized by a westward tilt with height that places

geopotential anomalies about 90 ~ out of phase between the lower and upper

boundaries. This can be inferred from the eddy meridional velocity v' =

ikq/,

which is contoured (solid/dashed lines) in Fig. 16.3a on a vertical section pass-

ing zonally through the center of the disturbance (y - 0).

Eddy geopotential and motion maximize at z = 0 and H in the form of two

edge waves that are sandwiched between the upper and lower boundaries. In

addition to driving air across mean isotherms, those boundaries trap instability,

which allows the disturbance to amplify. Each edge wave decays vertically with

the Rossby height scale H R - a-1. In the limit

Ikhl --+ c~, H R

is short enough

for the two edge waves to be isolated from one another. Because neither has

vertical phase tilt, hydrostatic balance implies a temperature perturbation that

is in phase with the geopotential perturbation (Problem 16.15). The perturba-

tion velocity v' is then everywhere in quadrature with 0', so the eddy heat flux

averaged over a wavelength v' 0' vanishes. Consequently, eddy motion does not

alter the baroclinic stratification of the mean state and no available potential

energy is released. It is for this reason that short wavelengths in the Eady

problem are neutral.

For a <

a c, H R

is long enough for the two edge waves to influence one

another. Phase-shifted, they produce the westward tilt apparent in Fig. 16.3a.

The temperature perturbation is then no longer in phase with the geopoten-

tial perturbation. Isentropes (dotted lines in Fig. 16.3a) actually tilt slightly

eastward with height to make 0' positively correlated with v" Cold air moves

equatorward (out of the page) and warm air moves poleward (into the page). 2

Both contribute positively to v' 0' to produce a poleward eddy heat flux, which

releases available potential energy. The mode's amplification is thus directly

related to its westward tilt with height.

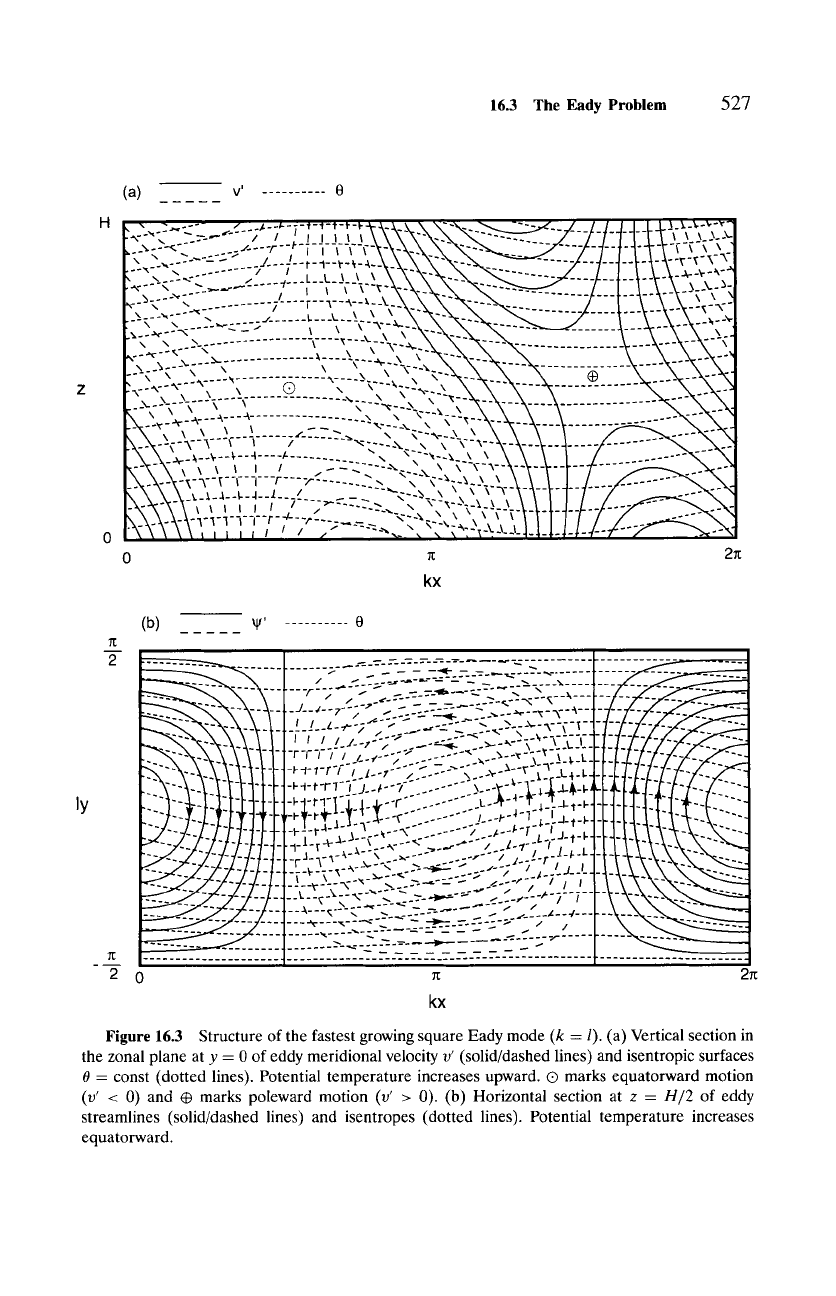

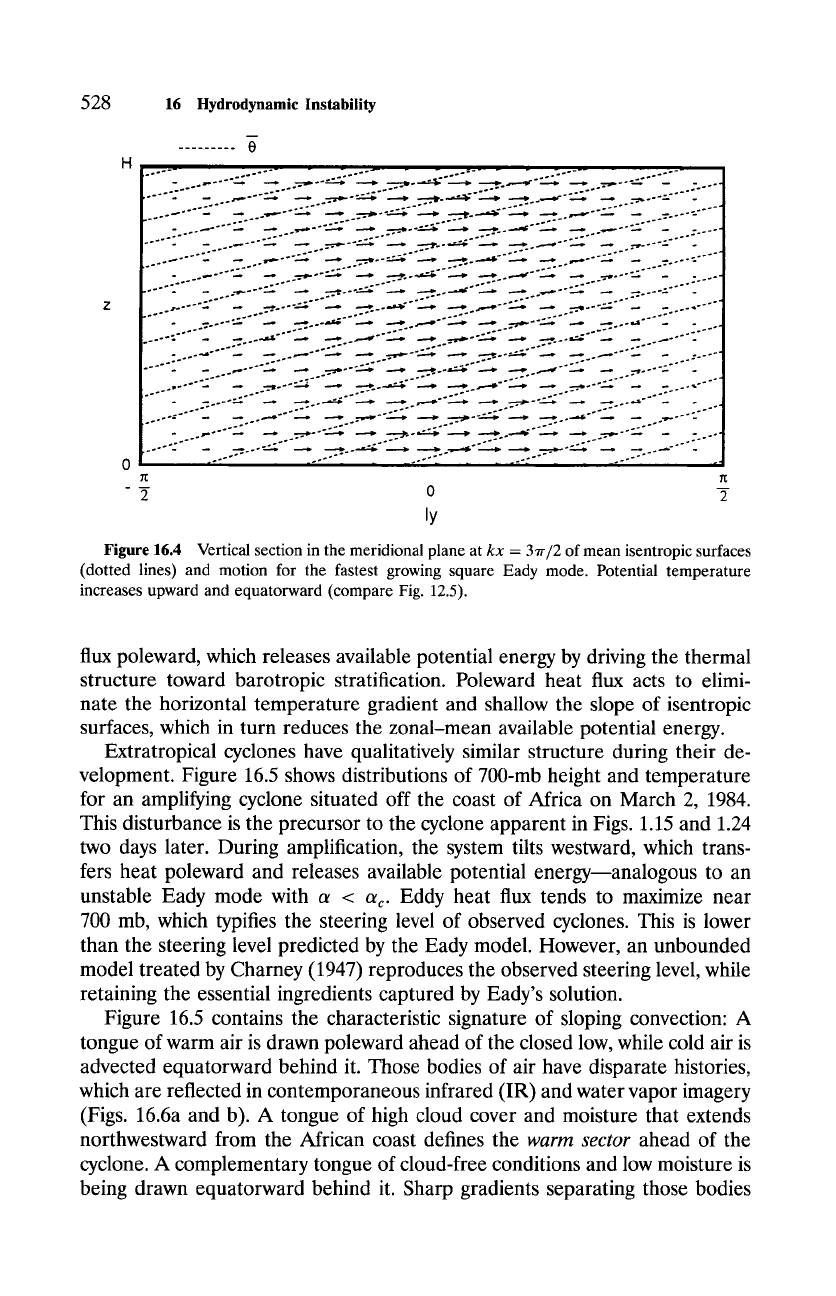

The streamfunction in a horizontal section at

z - H/2

(Fig. 16.3b) and

in a meridional section at

kx -

37r/2 (Fig. 16.4) illustrates that poleward-

moving air ascends, whereas, half a wavelength away, equatorward-moving air

descends. Characteristic of sloping convection, this is the same sense merid-

ional motion would have were it to move along zonal-mean isentropic surfaces

in Fig. 16.4 (dotted lines), which slope upward toward the pole. However,

meridional displacements of the fastest growing Eady mode have a slope at

midlevel which is only about half that of mean isentropic surfaces (Problem

16.18). Eddy motion directed across those surfaces advects high 0 poleward

and low 0 equatorward in adjacent branches of a cell, as is evident from isen-

tropes at midlevel (Fig. 16.3b). This asymmetric motion produces a net heat

2 In fact, v' and 0' are perfectly in phase at the steering level: z =

HI2.

16.3 The Eady Problem 527

(a) v' - ......... 0

v'~-'~: ..... ~---y-,-;-,--c-<-~k-\-N-\-&~ --~--Z:I-I 1-7-~-_c-_"~.:Q~-1

,,_.,..~ ..... __,,___,__,_,__,_,_,__ _ --. - .............

,

"" \ --',.

........ /

./ L

L ~ \ \ ""-- ... " .....................

-V.-~--~"

k .... <

-_ ...........

7:t

:_.,.;.:I

--'~,"":-"_ ........... ~----r--~--~--~--~-.." "" - ......... " ............. -_ _-\ ~--

k,_.-. ..... .

.'

-- -,-,--,--,-,---,----, ..... 2:. "\'" r --~___ "'" "

0 rt 2rt

kx

/1:

2

(b)

V'

- .........

O

T

---~ ...... :, .... ---L:-S-L'--'~ " - -_...~Z__-" .........

---~---r ..... "~" --.-~, ..... --'-"-<--',"- - ....

/. / ," .... ='--:."-"_ _".~------<--m--'--"

V-f- .:'- - "- - ,";, ~, .-:..~-:-----~-~S.".--.-:~--~-~ --~--

-~-l-.'--l--L-+--~ ," _.-----:-=" .:...--~-<-'-.-~--C-_Y:

1--r-r-cT~ z.~--':": ....... "~.-~--~--'~'i"~-[-

-~ + + ~-rr';" l.-,-"';';..

:->-~'. :~- ~--~-'; ~: Z ~:L:

r-P -~-r-r~-T~s -~-'-/"" . ...... L-@-~'T l'_[.i.~-~,

I-I" -v 1-r 1"1-1: I. ~--r'": ....... ::L. J~-'-~7, Z-~ ,-v.

~-P-~l-~'-'~] ' -l---e'" - ..... i .-~-~-7 ~ ~j t-~

-

-'- 4-~" "~" - .... ---T" -~-

- "l- -

"~" +t r ~a_~._c.~- ~.~,. .... .~ .... ~-, r ~.,.~_~_~.

-1" .-v.-r-'- ,, x__C-~, -- -:--- ~-':~'~'7 ~ / ~ L

-r- -[- -~'- x----,'" ,--->" / _-~--- ....

.,I._ .... V_---N--~- 3.._:.=....=--'- ..-- .,.,, .,~,,ot . / l I

i---~--~-~:-"--"--- ":--='-'~'~':" -.:-,:- -~- 7"- 7 -"

t

.... "~---~'" ~ ~--..----~.~ ... ~ I ....

Z--4---

...... 9 -~- - - -'~.--"~'~ "" _ _ _- --"----Z.->" / /

........ ~, .... ',,,.-~ .... -=--- _ -- .-. ...-. ~___~,,. .....

_ >_ .,~ _ _ _ -~- - -'='- ,-.-- -...-l~-'-- .......

_m

2

0 rt

2rt

kx

Figure 16.3 Structure of the fastest growing square Eady mode (k = I). (a) Vertical section in

the zonal plane at y = 0 of eddy meridional velocity v' (solid/dashed lines) and isentropic surfaces

0 = const (dotted lines). Potential temperature increases upward. | marks equatorward motion

(v' < 0) and @ marks poleward motion (v' > 0). (b) Horizontal section at z =

H/2

of eddy

streamlines (solid/dashed lines) and isentropes (dotted lines). Potential temperature increases

equatorward.

528

16

Hydrodynamic Instability

m

.......... 0

H

. ..o..- .... .., -.,, o~.,,,oO~ ~ __.~.~o--.r.:-~ ~ ..-.po..,.~~176 .-..,, .,,.,,-ooT.~ - .....

. ...,.---'.~ ...,, ..m,,..--_:~" ~ _.r~....,,,~r,"...-~ ~ .,.-~-~ ....,, _.,..-:.T, ~ _ . ..

..... "-" - .,,.---~'" ...- _.-.~,.~ .-.~.~176176 ~ .~,.--:.~" _.. ~ .... -~ .... .

Z ..... --=.'" -- ~ .... .=.z,'"_.., ...r:,...,,.~~ _...,,~ ...., ._,.--=.:-"_ _ ....----

.... . .. o~ .... ~ _.., _.~,,~ ~ ..rT~....~.z.~ ~ ~ ~ ..,..,~'~ ...,, ..~.o--~" .

...... ".~ .,, ._~.o~ _.., ..7~..o..,~.~ ~ ~ _..~~176 ~ ..~,~176 .,, _ ...,o-"

.... "." _ ~ .... ~ ._.,, .._~_......,,..~'....._~ ~ .,_..~'T.....~ ~ .-...=.,~-'-~.:-7, --4, ..., ....,,-'" -

0

-~

o 7

ly

Figure 16.4 Vertical section in the meridional plane at

kx

= 37r/2 of mean isentropic surfaces

(dotted lines) and motion for the fastest growing square Eady mode. Potential temperature

increases upward and equatorward (compare Fig. 12.5).

flux poleward, which releases available potential energy by driving the thermal

structure toward barotropic stratification. Poleward heat flux acts to elimi-

nate the horizontal temperature gradient and shallow the slope of isentropic

surfaces, which in turn reduces the zonal-mean available potential energy.

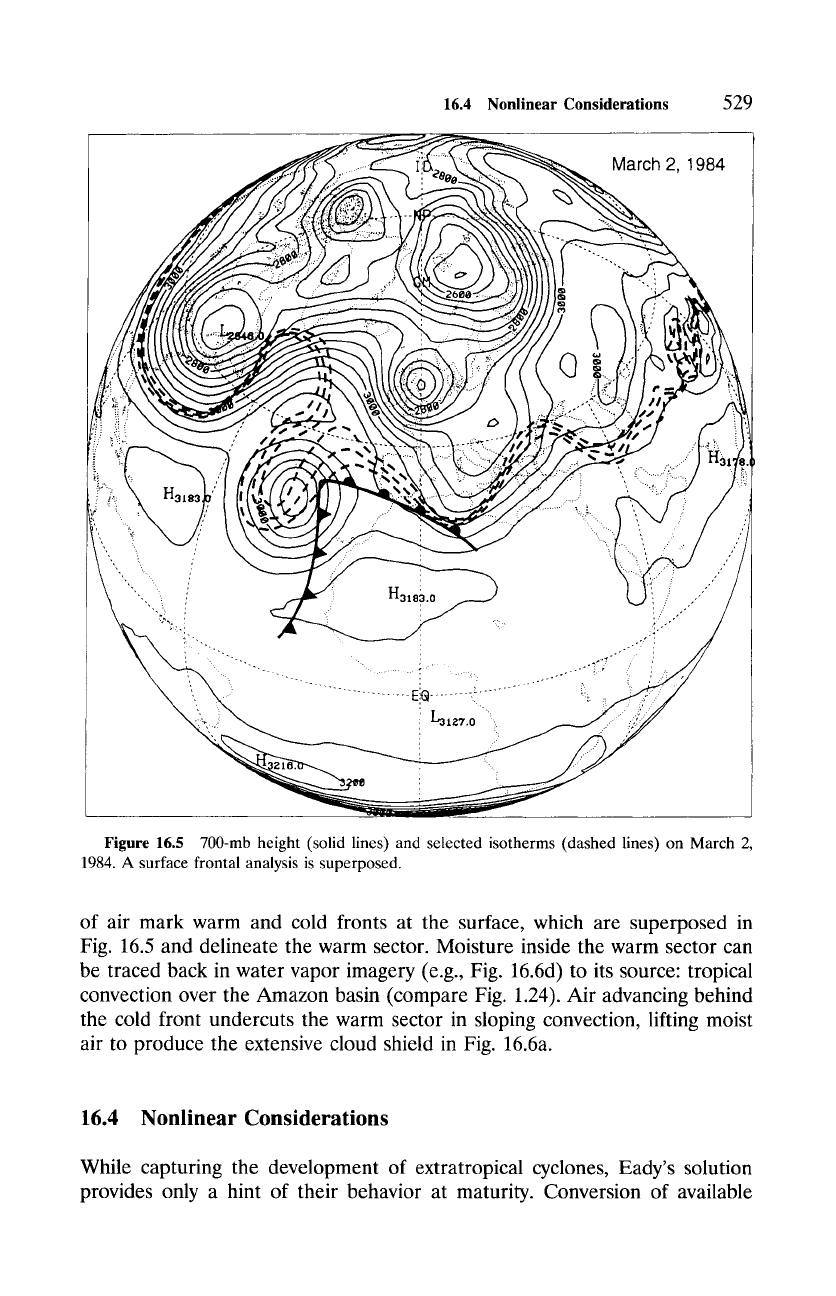

Extratropical cyclones have qualitatively similar structure during their de-

velopment. Figure 16.5 shows distributions of 700-mb height and temperature

for an amplifying cyclone situated off the coast of Africa on March 2, 1984.

This disturbance is the precursor to the cyclone apparent in Figs. 1.15 and 1.24

two days later. During amplification, the system tilts westward, which trans-

fers heat poleward and releases available potential energy--analogous to an

unstable Eady mode with c~ < a c. Eddy heat flux tends to maximize near

700 mb, which typifies the steering level of observed cyclones. This is lower

than the steering level predicted by the Eady model. However, an unbounded

model treated by Charney (1947) reproduces the observed steering level, while

retaining the essential ingredients captured by Eady's solution.

Figure 16.5 contains the characteristic signature of sloping convection: A

tongue of warm air is drawn poleward ahead of the closed low, while cold air is

advected equatorward behind it. Those bodies of air have disparate histories,

which are reflected in contemporaneous infrared (IR) and water vapor imagery

(Figs. 16.6a and b). A tongue of high cloud cover and moisture that extends

northwestward from the African coast defines the

warm sector

ahead of the

cyclone. A complementary tongue of cloud-free conditions and low moisture is

being drawn equatorward behind it. Sharp gradients separating those bodies

16.4 Nonlinear Considerations

529

March 2, 1984

""-..,

,, ......,..:

......... ~i...}::.ill.... - ....... -~, ......" .....

, .~.. /

H3183.o ~ i

..:.

,

...

?... -... .

. -.. :.. .

"...... "._..... _. _ '" ..................... ~"" ......... .. ...... -::..: .. -..... :...

::- - ..................... E,~ ........ ~! .............. ~:

....

".. ..

.

, .

~

~ ', .~.

Figure 16.5 700-mb height (solid lines) and selected isotherms (dashed lines) on March

2,

1984. A

surface frontal analysis is superposed.

of air mark warm and cold fronts at the surface, which are superposed in

Fig. 16.5 and delineate the warm sector. Moisture inside the warm sector can

be traced back in water vapor imagery (e.g., Fig. 16.6d) to its source: tropical

convection over the Amazon basin (compare Fig. 1.24). Air advancing behind

the cold front undercuts the warm sector in sloping convection, lifting moist

air to produce the extensive cloud shield in Fig. 16.6a.

16.4 Nonlinear Considerations

While capturing the development of extratropical cyclones, Eady's solution

provides only a hint of their behavior at maturity. Conversion of available