Mattingly J.D., Heiser W.H., Pratt D.T. Aircraft Engine Design

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

DESIGN: INLETS AND EXHAUST NOZZLES

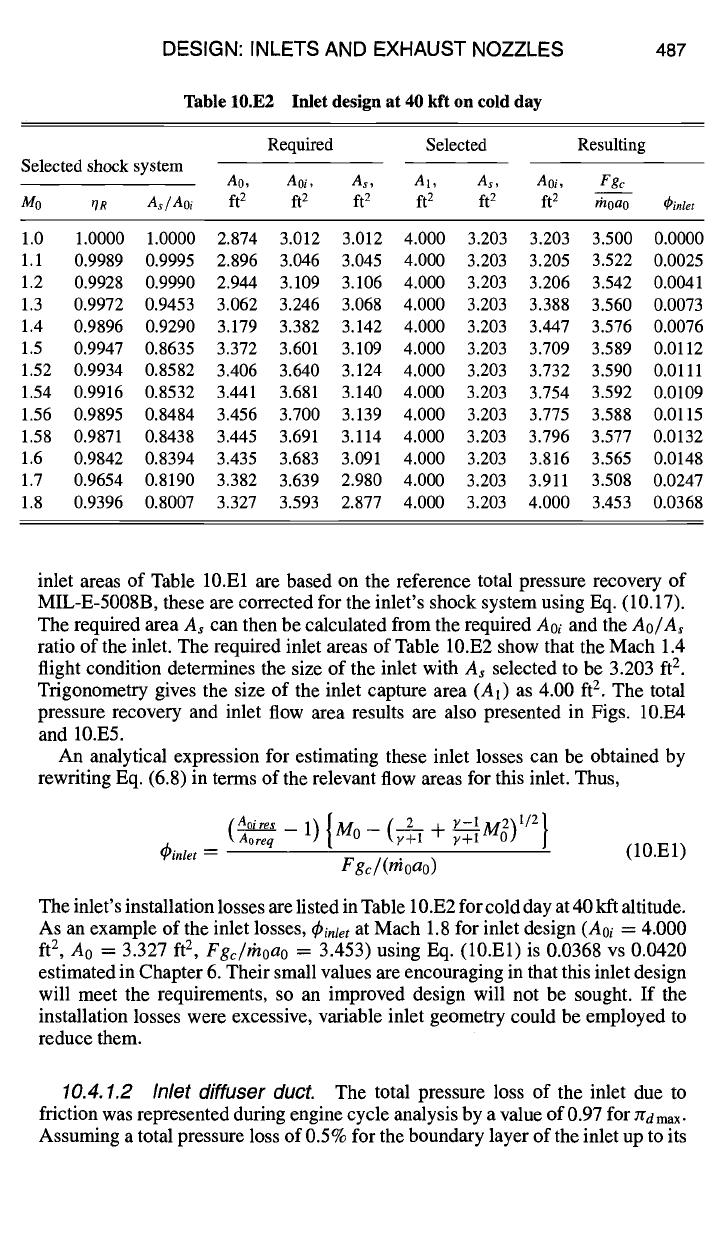

Table 10.E2 Inlet design at 40 kft on cold day

487

Required Selected Resulting

Selected shock system

AO,

Aoi, As, A1, As, Aoi, Fgc

Mo

~R

As/Aoi

ft 2 ft 2 ft 2 ft 2 ft 2 ft 2 Ih0a0

~inlet

1.0 1.0000 1.0000 2.874 3.012 3.012 4.000 3.203 3.203 3.500 0.0000

1.1 0.9989 0.9995 2.896 3.046 3.045 4.000 3.203 3.205 3.522 0.0025

1.2 0.9928 0.9990 2.944 3.109 3.106 4.000 3.203 3.206 3.542 0.0041

1.3 0.9972 0.9453 3.062 3.246 3.068 4.000 3.203 3.388 3.560 0.0073

1.4 0.9896 0.9290 3.179 3.382 3.142 4.000 3.203 3.447 3.576 0.0076

1.5 0.9947 0.8635 3.372 3.601 3.109 4.000 3.203 3.709 3.589 0.0112

1.52 0.9934 0.8582 3.406 3.640 3.124 4.000 3.203 3.732 3.590 0.0111

1.54 0.9916 0.8532 3.441 3.681 3.140 4.000 3.203 3.754 3.592 0.0109

1.56 0.9895 0.8484 3.456 3.700 3.139 4.000 3.203 3.775 3.588 0.0115

1.58 0.9871 0.8438 3.445 3.691 3.114 4.000 3.203 3.796 3.577 0.0132

1.6 0.9842 0.8394 3.435 3.683 3.091 4.000 3.203 3.816 3.565 0.0148

1.7 0.9654 0.8190 3.382 3.639 2.980 4.000 3.203 3.911 3.508 0.0247

1.8 0.9396 0.8007 3.327 3.593 2.877 4.000 3.203 4.000 3.453 0.0368

inlet areas of Table 10.El are based on the reference total pressure recovery of

MIL-E-5008B, these are corrected for the inlet's shock system using Eq. (10.17).

The required area A~ can then be calculated from the required Aoi and the

Ao/A~

ratio of the inlet. The required inlet areas of Table 10.E2 show that the Mach 1.4

flight condition determines the size of the inlet with A~ selected to be 3.203 ft 2.

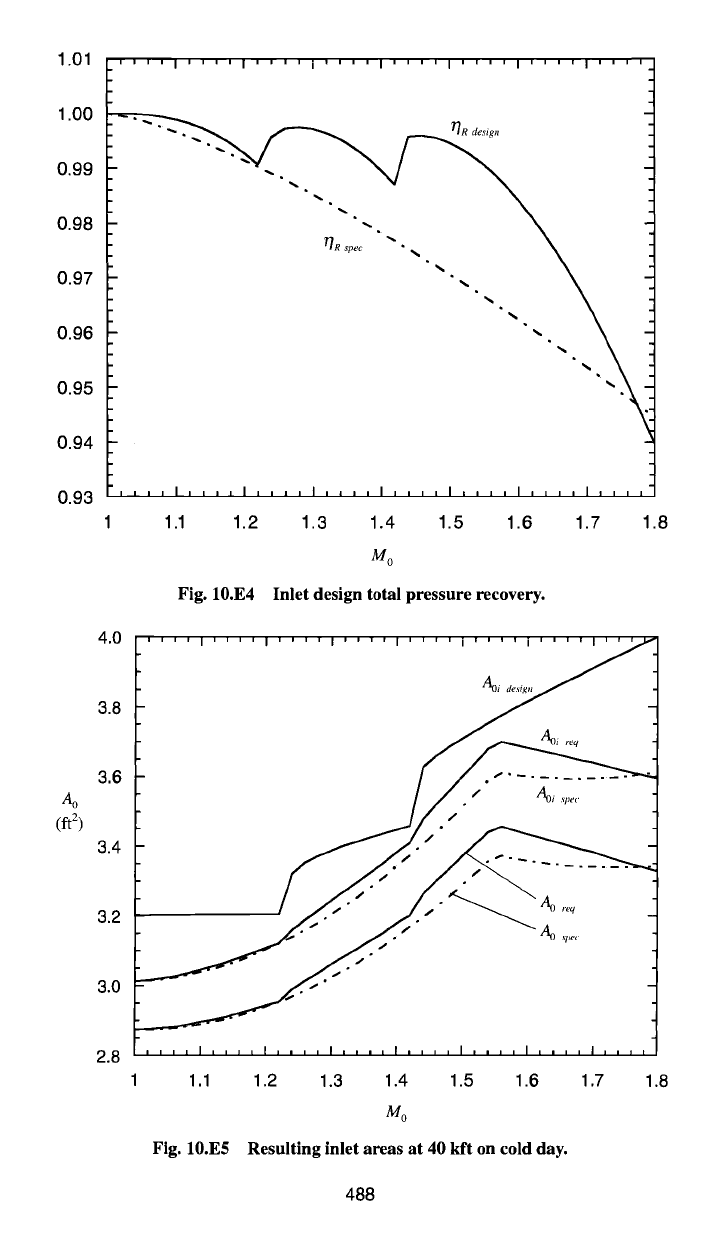

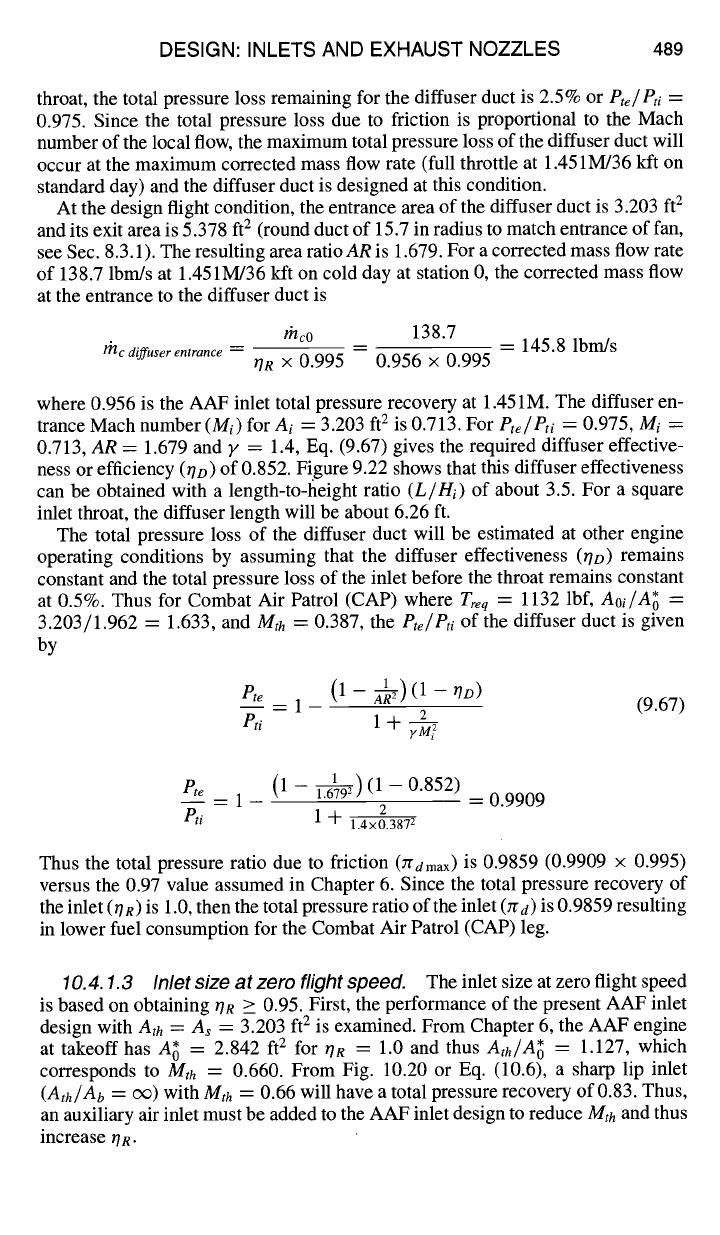

Trigonometry gives the size of the inlet capture area (A1) as 4.00 ft 2. The total

pressure recovery and inlet flow area results are also presented in Figs. 10.E4

and 10.E5.

An analytical expression for estimating these inlet losses can be obtained by

rewriting Eq. (6.8) in terms of the relevant flow areas for this inlet. Thus,

(Ao/re~ _ 1) {Mo _ (7~y - t-

Y-1M2~l/2~

Aoreq ~ O] J

~inlet =

(10.El)

Fgc/(nioao)

The inlet's installation losses are listed in Table 10.E2 for cold day at 40 kft altitude.

As an example of the inlet losses,

(/)inlet

at Mach 1.8 for inlet design (Aoi

=

4.000

ft 2, A0 = 3.327 ft 2,

Fgc/rhoao

= 3.453) using Eq. (10.El) is 0.0368 vs 0.0420

estimated in Chapter 6. Their small values are encouraging in that this inlet design

will meet the requirements, so an improved design will not be sought. If the

installation losses were excessive, variable inlet geometry could be employed to

reduce them.

10.4.1.2 Inlet diffuser duct.

The total pressure loss of the inlet due to

friction was represented during engine cycle analysis by a value of 0.97 for ]rd max.

Assuming a total pressure loss of 0.5% for the boundary layer of the inlet up to its

1.01

1.00

0.99

0.98

0.97

0.96

0.95

0.94

0.93

4.0

3.8

3.6

Ao

(ft 2)

3.4

3.2

3.0

2.8

''''I''''I''''I''''I''''I''''I''''I''''

~ec "" • ,,,, \, .,,,,,,,, ,,

, , , , I , , , , I , , , , I , , , , I , , , , I , , , , I , , , , I , , , ,

1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8

Mo

Fig. 10.E4 Inlet design total pressure recovery.

.... , .... , .... , .... , .... ,,-,::,,~,,,,,,:7

/° -

/-/°/

1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8

Mo

Fig. 10.E5 Resulting inlet areas at 40 kft on cold day.

488

DESIGN: INLETS AND EXHAUST NOZZLES 489

throat, the total pressure loss remaining for the diffuser duct is 2.5% or

P~e/P~i =

0.975. Since the total pressure loss due to friction is proportional to the Mach

number of the local flow, the maximum total pressure loss of the diffuser duct will

occur at the maximum corrected mass flow rate (full throttle at 1.451M/36 kft on

standard day) and the diffuser duct is designed at this condition.

At the design flight condition, the entrance area of the diffuser duct is 3.203 ft 2

and its exit area is 5.378 ft 2 (round duct of 15.7 in radius to match entrance of fan,

see Sec. 8.3.1). The resulting area ratio

AR

is 1.679. For a corrected mass flow rate

of 138.7 lbm/s at 1.451M/36 kft on cold day at station 0, the corrected mass flow

at the entrance to the diffuser duct is

mc

diffuser entrance --

rhc0 138.7

~R x 0.995 0.956 x 0.995

-- 145.8 lbm/s

where 0.956 is the AAF inlet total pressure recovery at 1.451M. The diffuser en-

trance Mach number

(Mi)

for

Ai

= 3.203

ft 2

is 0.713. For

Pte/Pti

= 0.975,

Mi =

0.713,

AR

= 1.679 and y = 1.4, Eq. (9.67) gives the required diffuser effective-

ness or efficiency 0/D) of 0.852. Figure 9.22 shows that this diffuser effectiveness

can be obtained with a length-to-height ratio

(L/Hi)

of about 3.5. For a square

inlet throat, the diffuser length will be about 6.26 ft.

The total pressure loss of the diffuser duct will be estimated at other engine

operating conditions by assuming that the diffuser effectiveness (0D) remains

constant and the total pressure loss of the inlet before the throat remains constant

at 0.5%. Thus for Combat Air Patrol (CAP) where

Treq

= 1132 lbf,

Aoi/A~ =

3.203/1.962 = 1.633, and

Mth

= 0.387, the

Pte/Pti

of the diffuser duct is given

by

--= (1 - ~) (1 - ~/D)

Pte

1 - (9.67)

P,i 1 + y~2

1-- 1

P e = 1 - ~) (1 - 0.852)

2

Pti

1 --1- 1.4x0.3872

= 0.9909

Thus the total pressure ratio due to friction (rramax) is 0.9859 (0.9909 × 0.995)

versus the 0.97 value assumed in Chapter 6. Since the total pressure recovery of

the inlet (OR) is 1.0, then the total pressure ratio of the inlet (red) is 0.9859 resulting

in lower fuel consumption for the Combat Air Patrol (CAP) leg.

10.4.1.3 Inlet size at zero flight speed.

The inlet size at zero flight speed

is based on obtaining ~TR >_ 0.95. First, the performance of the present AAF inlet

design with

Ath = As

= 3.203

ft 2

is examined. From Chapter 6, the AAF engine

at takeoff has A~ = 2.842

ft 2

for OR = 1.0 and thus

Ath/A~

= 1.127, which

corresponds to

Mth

= 0.660. From Fig. 10.20 or Eq. (10.6), a sharp lip inlet

(Ath/Ab

= oo) with

Mth

= 0.66 will have a total pressure recovery of 0.83. Thus,

an auxiliary air inlet must be added to the AAF inlet design to reduce

Mth

and thus

increase ~/R.

490 AIRCRAFT ENGINE DESIGN

Designing for OR = 0.95, Eq. (10.6) gives Mth = 0.285. The required one-

dimensional inlet throat area

(Ath)

is determined using

rhcV'~,d

Ath

= (10.E2)

PstdMFP( Mth )

Thus

132.34~/518.7

Ath

= = 5.709 ft 2

2116 x 0.2495

and an auxiliary air inlet whose throat area is 2.506 ft 2 (5.709 - 3.203) needs

to be added to the AAF inlet design to meet the total pressure recovery goal

of 0.95.

The AAF inlet with auxiliary air inlet door now has a total pressure recovery of

0.95 and

~inlet

of 0.0578 (assuming A1 =

Ath)

as compared to the Chapter 6 values

of 0R = 1.0 and

dPinlet

= 0.0929. The total pressure ratio of the diffuser duct with

AR

~ 1 (5.378/5.709) is one. Thus,

7~dmax

is 0.995 and Zrd = (0.95)(0.995) =

0.9452.

10.4.1.4 Inlet performance during takeoff.

Flow separation from the in-

side surface of the sharp lips of the inlet must be reduced during subsonic flight.

An auxiliary air inlet was added to the AAF inlet to reduce the external flow sepa-

ration at zero flight speed. This same auxiliary air inlet can be used to reduce flow

separation at other subsonic flight conditions that have low total pressure recovery

(0R) with accompanying high inlet throat Mach number. The area ratio

Ao/Ath

can

be used to identify those flight conditions at which lip flow separation may be a

problem (see Fig. 10.58). Only Segments A, B, and C of Mission Phase 1-2 have

A0 larger than 4.0

ft 2

and Segments B and C have not yet been analyzed.

It is assumed that the auxiliary air inlet sized for zero flight speed is also used for

Segments B and C, also giving them a total inlet throat area of 5.709 ft e. Off-design

engine cycle analyses give the required reference

Aowec

for Segments B and C of

16.55

ft 2

and 9.154 ft 2, respectively. The resulting

Ao/Ath,

Mth, and ~/n (estimated

from Fig. 10.58) are tabulated:

Segment

Mo Ao/ Ath

Mth

OR

B 0.10 2.899 0.205 0.98

C 0.18 1.603 0.396 0.97

Based on a constant total pressure effectiveness (0D) of the diffuser duct and

Eq. (9.67), the inlet total pressure ratio (Zrd) for Segments B and C are 0.97 and

0.98, respectively, as compared to the value of 0.97 used for both in the engine

cycle analysis.

10.4.1.5 AAF inlet performance.

The performance of the AAF inlet de-

sign can now be calculated at all flight conditions and compared to the estimates

DESIGN: INLETS AND EXHAUST NOZZLES

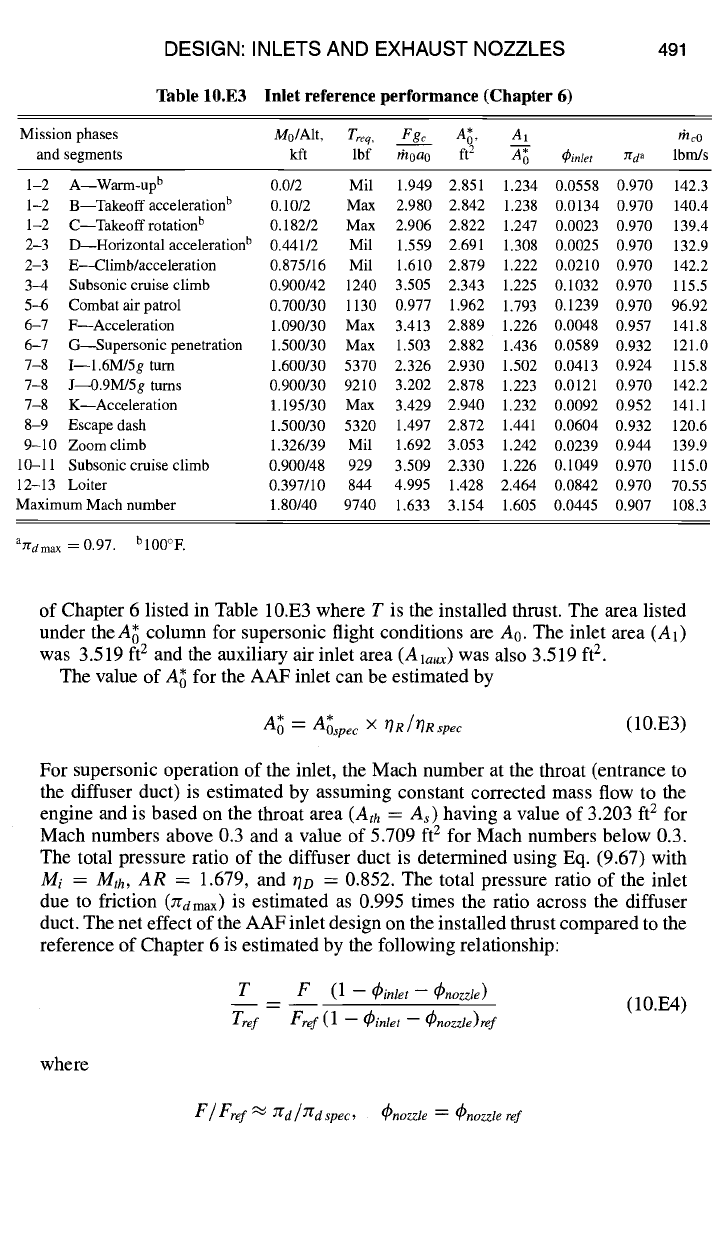

Table 10,E3 Inlet reference performance (Chapter 6)

491

Mission phases

Mo/Alt,

Treq,

Fgc A~,

AI rhcO

and segments

kft lbf

&oao

ft 2

A-~o

¢inlet

Yrda

lbm/s

1-2 A--Warm-up b 0.0/2 Mil 1.949 2.851 1.234 0.0558 0.970 142.3

1-2 B--Takeoff acceleration b 0.10/2 Max 2.980 2.842 1.238 0.0134 0.970 140.4

1-2 C--Takeoffrotation b 0.182/2 Max 2.906 2.822 1.247 0.0023 0.970 139.4

2-3 D--Horizontal acceleration b 0.441/2 Mil 1.559 2.691 1.308 0.0025 0.970 132.9

2-3

E--Climb~acceleration

0.875/16 Mil 1.610 2.879 1.222 0.0210 0.970 142.2

3-4

Subsonic cruise climb

0.900/42 1240 3.505 2.343 1.225 0.1032 0.970 115.5

5-45

Combat air patrol

0.700/30 1130 0.977 1.962 1.793 0.1239 0.970 96.92

6-7 F--Acceleration 1.090/30 Max 3.413 2.889 1.226 0.0048 0.957 141.8

6-7

G--Supersonic penetration

1.500/30 Max 1.503 2.882 1.436 0.0589 0.932 121.0

7-8 I--1.6M/5g turn 1.600/30 5370 2.326 2.930 1.502 0.0413 0.924 115.8

7-8 J~0.9M/5g

turns

0.900/30 9210 3.202 2.878 1.223 0.0121 0.970 142.2

7-8 K--Acceleration 1.195/30 Max 3.429 2.940 1.232 0.0092 0.952 141.1

8-9

Escape dash

1.500/30 5320 1.497 2.872 1.441 0.0604 0.932 120.6

9-10 Zoomclimb 1.326/39 Mil 1.692 3.053 1.242 0.0239 0.944 139.9

10-11

Subsonic cruise climb

0.900/48 929 3.509 2.330 1.226 0.1049 0.970 115.0

12-13 Loiter 0.397/10 844 4.995 1.428 2.464 0.0842 0.970 70.55

MaximumMach number

1.80/40 9740 1.633 3.154 1.605 0.0445 0.907 108.3

aT~dmax = 0.97.

bl00°F.

of Chapter 6 listed in Table 10.E3 where T is the installed thrust. The area listed

under theA~ column for supersonic flight conditions are A0. The inlet area (At)

was 3.519 ft 2 and the auxiliary air inlet area (Ala~,) was also 3.519 ft 2.

The value of A; for the AAF inlet can be estimated by

A~ = *

Aospec

× OR/ORspec

(10.E3)

For supersonic operation of the inlet, the Mach number at the throat (entrance to

the diffuser duct) is estimated by assuming constant corrected mass flow to the

engine and is based on the throat area

(Ath = As)

having a value of 3.203 ft 2 for

Mach numbers above 0.3 and a value of 5.709 ft 2 for Mach numbers below 0.3.

The total pressure ratio of the diffuser duct is determined using Eq. (9.67) with

Mi = Mth, AR

= 1.679, and 0o = 0.852. The total pressure ratio of the inlet

due to friction (:rdm~x) is estimated as 0.995 times the ratio across the diffuser

duct. The net effect of the AAF inlet design on the installed thrust compared to the

reference of Chapter 6 is estimated by the following relationship:

T F

(1 --

(~inlet -- (Pnozzle)

(10.E4)

Tre f Ere f

(1

-

(/)inlet -- (~nozzle)ref

where

F / Fref ~ Zr d / Zr d ~pec ,

~.ozzl~

= Cnozzte ref

492 AIRCRAFT ENGINE DESIGN

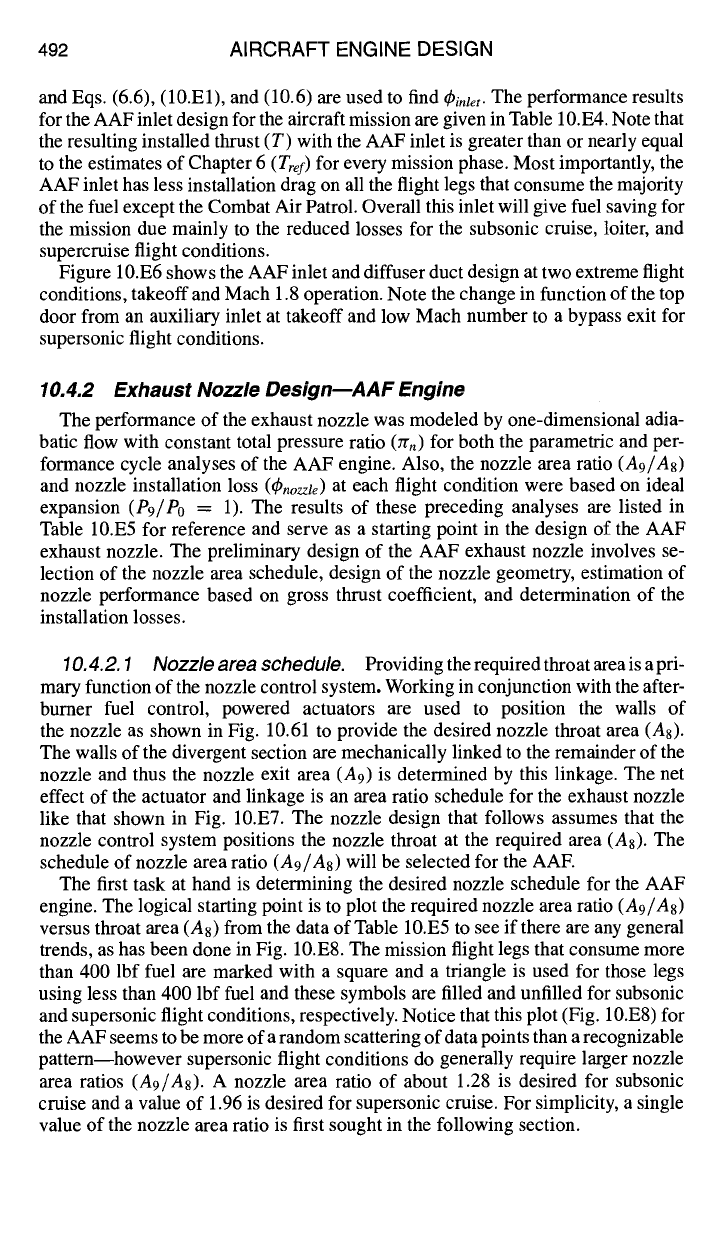

and Eqs. (6.6), (10.El), and (10.6) are used to find

~inlet.

The performance results

for the AAF inlet design for the aircraft mission are given in Table 10.E4. Note that

the resulting installed thrust (T) with the AAF inlet is greater than or nearly equal

to the estimates of Chapter 6

(Trey)

for every mission phase. Most importantly, the

AAF inlet has less installation drag on all the flight legs that consume the majority

of the fuel except the Combat Air Patrol. Overall this inlet will give fuel saving for

the mission due mainly to the reduced losses for the subsonic cruise, loiter, and

supercruise flight conditions.

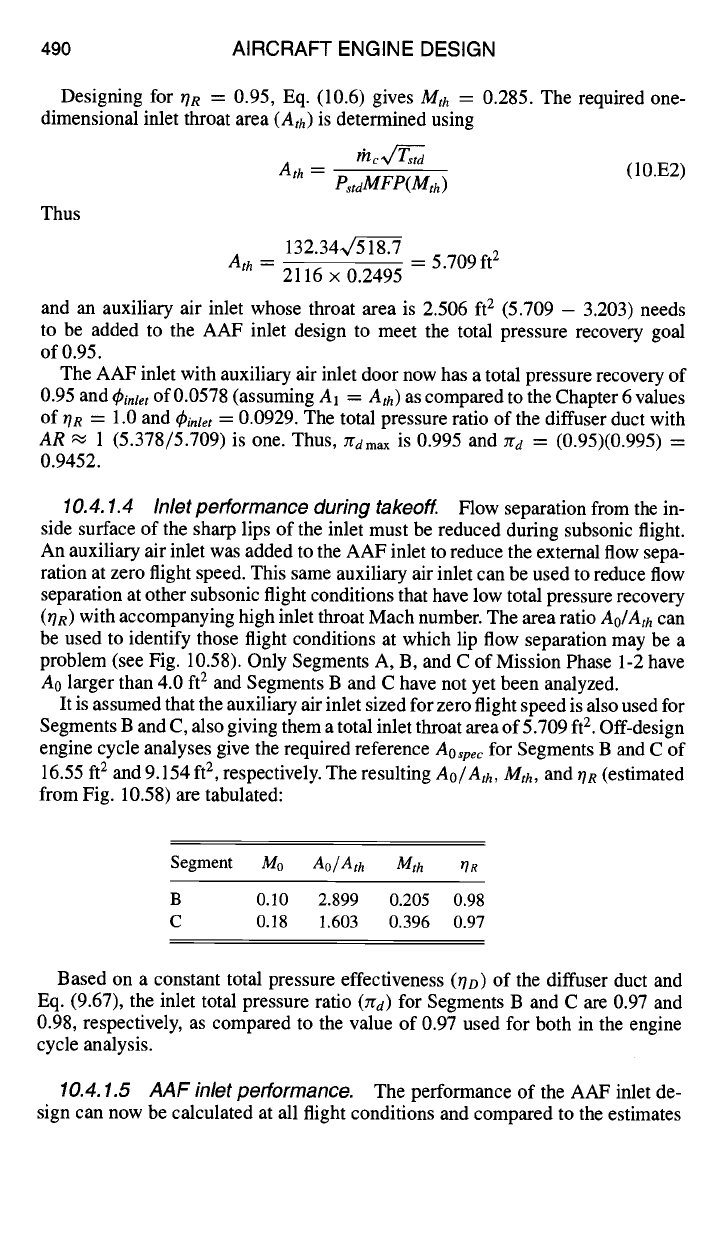

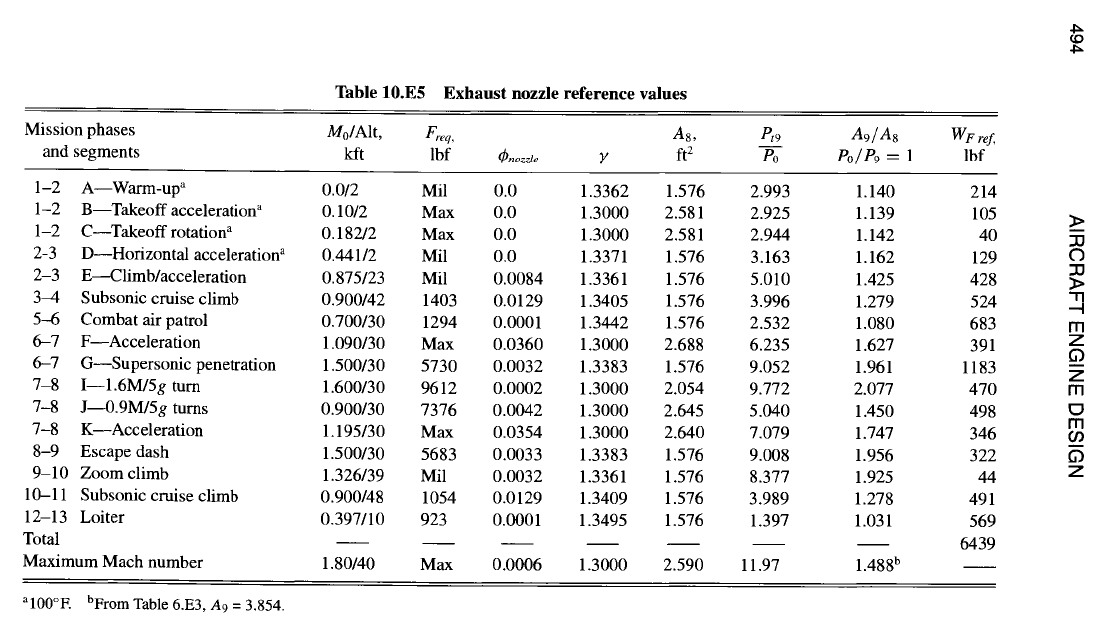

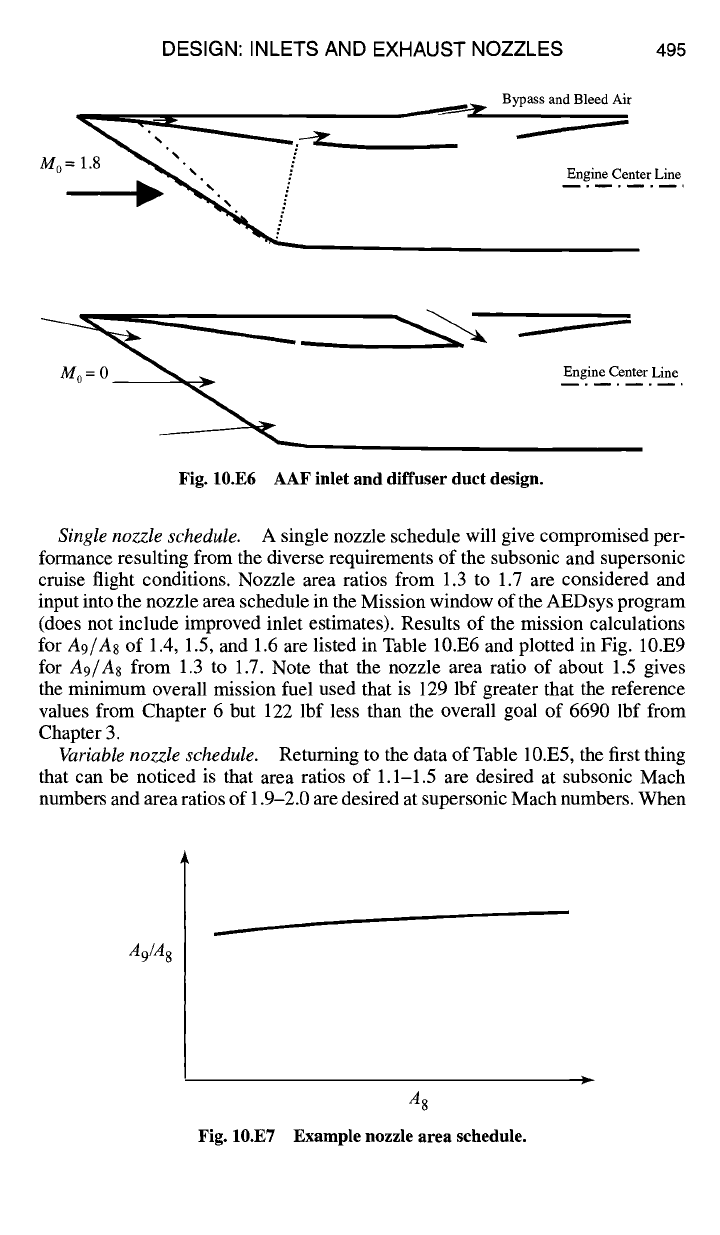

Figure 10.E6 shows the AAF inlet and diffuser duct design at two extreme flight

conditions, takeoff and Mach 1.8 operation. Note the change in function of the top

door from an auxiliary inlet at takeoff and low Mach number to a bypass exit for

supersonic flight conditions.

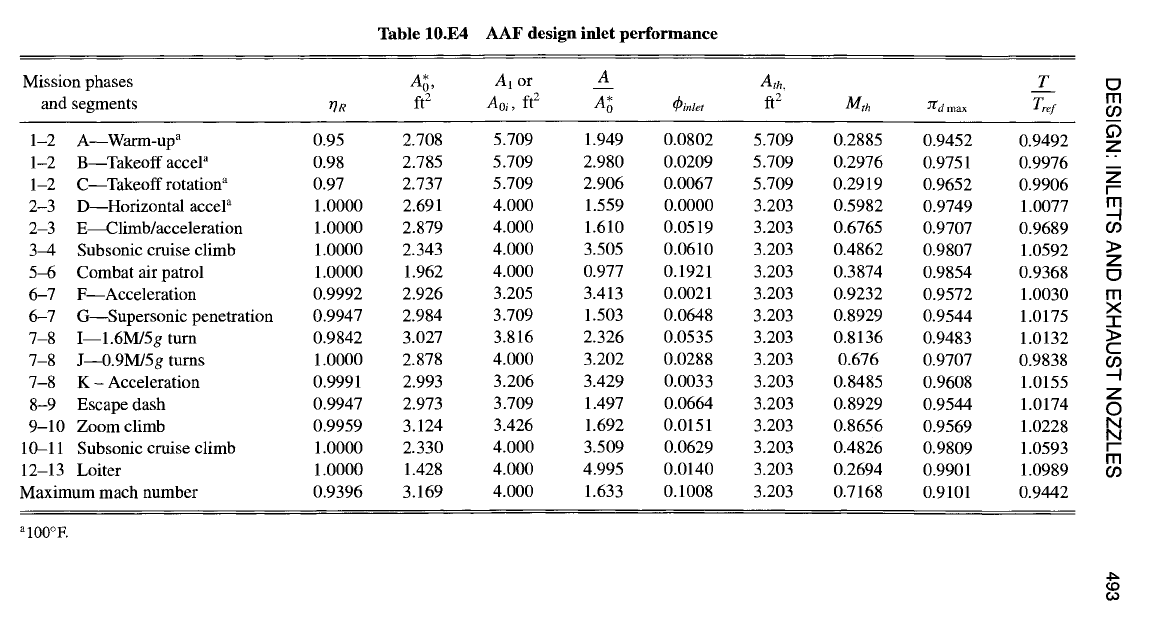

10.4.2 Exhaust Nozzle Design--AAF Engine

The performance of the exhaust nozzle was modeled by one-dimensional adia-

batic flow with constant total pressure ratio (zrn) for both the parametric and per-

formance cycle analyses of the AAF engine. Also, the nozzle area ratio (A9/A8)

and nozzle installation loss (q~nozzte) at each flight condition were based on ideal

expansion (P9/Po = 1). The results of these preceding analyses are listed in

Table 10.E5 for reference and serve as a starting point in the design of the AAF

exhaust nozzle. The preliminary design of the AAF exhaust nozzle involves se-

lection of the nozzle area schedule, design of the nozzle geometry, estimation of

nozzle performance based on gross thrust coefficient, and determination of the

installation losses.

10.4.2.1 Nozzle area schedule. Providing the required throat area is a pri-

mary function of the nozzle control system. Working in conjunction with the after-

burner fuel control, powered actuators are used to position the walls of

the nozzle as shown in Fig. 10.61 to provide the desired nozzle throat area (A8).

The walls of the divergent section are mechanically linked to the remainder of the

nozzle and thus the nozzle exit

area (A9)

is determined by this linkage. The net

effect of the actuator and linkage is an area ratio schedule for the exhaust nozzle

like that shown in Fig. 10.E7. The nozzle design that follows assumes that the

nozzle control system positions the nozzle throat at the required area (As). The

schedule of nozzle area ratio (A9/A8) will be selected for the AAE

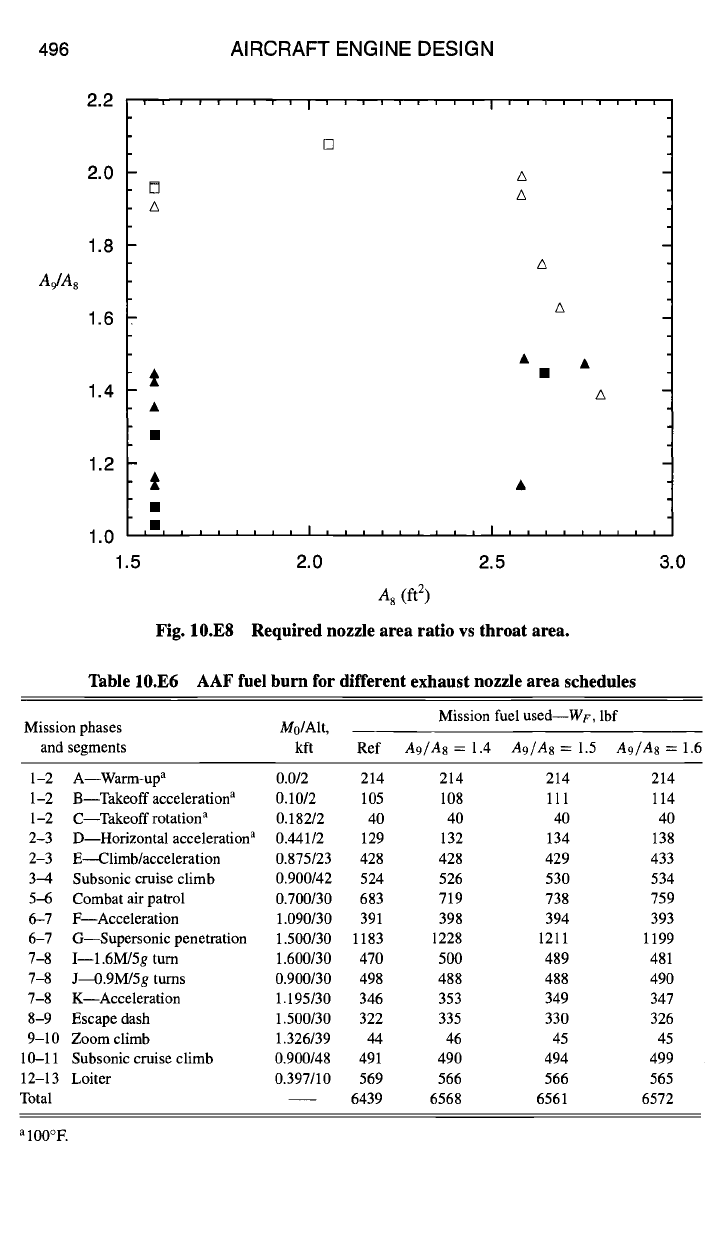

The first task at hand is determining the desired nozzle schedule for the AAF

engine. The logical starting point is to plot the required nozzle area ratio (Ag/As)

versus throat area (A8) from the data of Table 10.E5 to see if there are any general

trends, as has been done in Fig. 10.ES. The mission flight legs that consume more

than 400 lbf fuel are marked with a square and a triangle is used for those legs

using less than 400 lbf fuel and these symbols are filled and unfilled for subsonic

and supersonic flight conditions, respectively. Notice that this plot (Fig. 10.E8) for

the AAF seems to be more of a random scattering of data points than a recognizable

pattern--however supersonic flight conditions do generally require larger nozzle

area ratios (A9/A8). A nozzle area ratio of about 1.28 is desired for subsonic

cruise and a value of 1.96 is desired for supersonic cruise. For simplicity, a single

value of the nozzle area ratio is first sought in the following section.

DESIGN: INLETS AND EXHAUST NOZZLES 493

=

.-~c4

oo~o~o~o~~o

ooooooooooooooooo

ooooooooooooooooo

~o~~o~o~o~

~oooo~o~ooo

Oooooo~oo~ooo~ooo

~oooo~o~ooo

oooo~o~oo~

Oooo~o~o~

O

i

- ~b4

r.~ {,,J ~,.

494 AIRCRAFT ENGINE DESIGN

_=

N

l

O O

II

~5

DESIGN: INLETS AND EXHAUST NOZZLES 495

M o = 1.8 • ...

Bypass and Bleed Air

Engine Center Line

Engine Center Line

Fig. 10.E6 AAF inlet and diffuser duct design.

Single nozzle schedule.

A single nozzle schedule will give compromised per-

formance resulting from the diverse requirements of the subsonic and supersonic

cruise flight conditions. Nozzle area ratios from 1.3 to 1.7 are considered and

input into the nozzle area schedule in the Mission window of the AEDsys program

(does not include improved inlet estimates). Results of the mission calculations

for

A9/A8

of 1.4, 1.5, and 1.6 are listed in Table 10.E6 and plotted in Fig. 10.E9

for

A9/A8

from 1.3 to 1.7. Note that the nozzle area ratio of about 1.5 gives

the minimum overall mission fuel used that is 129 lbf greater that the reference

values from Chapter 6 but 122 lbf less than the overall goal of 6690 lbf from

Chapter 3.

Variable nozzle schedule.

Returning to the data of Table 10.E5, the first thing

that can be noticed is that area ratios of 1.1-1.5 are desired at subsonic Mach

numbers and area ratios of 1.9-2.0 are desired at supersonic Mach numbers. When

A9/A 8

Fig. 10.E7

A 8

Example nozzle area schedule.

496 AIRCRAFT ENGINE DESIGN

A#A8

2.2

2.0

1.8

1.6

1.4

1.2

1.0

1.5

' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' I ' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' '

A

A

A

A

t

ill i i i i i i i I i i i i i i I I I I i i i i i i i i i

2.0 2.5 3.0

A 8 (ft 2)

Fig. 10.E8 Required nozzle area ratio vs throat area.

Table 10.E6 AAF fuel burn for different exhaust nozzle area schedules

Mission phases M0/Alt,

and segments kft

Mission fuel used--WE, lbf

Ref

A9/A8

= 1.4

A9/A8

= 1.5

A9/A8

= 1.6

1-2 A--Warm-up a 0.0/2 214

1-2 B--Takeoff acceleration a 0.10/2 105

1-2 C--Takeoff rotation a 0.182/2 40

2-3 D--Horizontal acceleration a 0.441/2 129

2-3 E---Climb/acceleration 0.875/23 428

3-4 Subsonic cruise climb 0.900/42 524

5-6 Combat air patrol 0.700/30 683

6-7 F--Acceleration 1.090/30 391

6-7 G--Supersonic penetration 1.500/30 1183

7-8 I--1.6M/5g turn 1.600/30 470

7-8 J~.9M/5g tums 0.900/30 498

7-8 K--Acceleration 1.195/30 346

8-9 Escape dash 1.500/30 322

9-10 Zoom climb 1.326/39 44

10-11 Subsonic cruise climb 0.900/48 491

12-13 Loiter 0.397/10 569

Total 6439

214 214 214

108 111 114

40 40 40

132 134 138

428 429 433

526 530 534

719 738 759

398 394 393

1228 1211 1199

500 489 481

488 488 490

353 349 347

335 330 326

46 45 45

490 494 499

566 566 565

6568 6561 6572

alOO°E