Malley M.C. Radioactivity: A History of a Mysterious Science

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

APPENDIX 2

218

Radium

Series

Atomic

weight

3·30 cms.

4·16 ,,

4·75 ,,

6·57 ,,

3·77 ,,

—

—

—

—

2000 yrs.

3·85 days

3·0 mins.

19·5 mins.

136 days

5·0 days

16·5 yrs.

1·4 mins.

26·8 mins.

1 gr.

5·7 × 10

–6

gr.

3·1 × 10

–9

,,

2·0 × 10

–8

,,

1·9 × 10

–4

,,

7·1 × 10

–6

,,

8·6 × 10

–3

,,

—

2·7 × 10

–8

,,

226

222

218

214

210

210

210

—

214

α + slow β

α

α

α

+β + γ

α

β

+ γ

slow β

β

β

+ γ

Half-value

period

Weight

per gram

of radium

Radiation

Radium Series.

Range of

α rays at

15° C.

Radium

Ra. Emanation

Radium A

Radium C

Radium F

Radium E

Radium D

Ra. C

2

Radium B

Actinium

Series

Atomic

weight

A

A

A – 4

A – 8

A – 12

A – 16

A – 16

A – 20

?

19·5 days

10·2 days

3·9 secs.

·002 sec.

36 mins.

2·1 mins.

4·71 mins.

rayless

α + β

α

α

α

slow β

α

β

+ γ

—

4·60 cms.

4·40 ,,

5·70 ,,

6·50 ,,

—

5·40 ,,

—

Half-value

period

Actinium Series.

Radiation

Range of

α rays at

15° C.

Actinium . . .

Radio-actinium

Actinium X . . .

Emanation . . .

Actinium A . . .

Actinium B . . .

Actinium C . . .

Actinium D . . .

FAMILY TREES FOR RADIOACTIVE ELEMENTS

219

orium

Series

Atomic

weight

Weight per

10

6

grams

thorium

Half-value

period

orium Series.

Radiation

Range

α rays

15° C.

2·72 cms.

3·87 ,,

4·3 ,,

5·0 ,,

5·7 ,,

4·8 ,,

8·6 ,,

—

—

—

—

1·3× 10

10

yrs.

2 yrs.

3·65 days

54 secs.

0·14 secs.

60 mins.

very short (?)

5·5 yrs.

6·2 hrs.

10·6 hrs.

3·1 mins.

232

228

224

220

216

212

212

228

228

212

208

10

9

mg.

0·15 ,,

7·4 × 10

–4

,,

1·2 × 10

–7

,,

3·1 × 10

–10

,,

7·9 × 10

–6

,,

—

0·42 mg.

5·2 × 10

–5

mg.

8·5 × 10

–5

,,

1·3 × 10

–7

,,

α

α

α

+ β

α

α

α

+ β

α

rayless

β + γ

β

+ γ

β

+ γ

orium . . .

Radiothorium

orium X . . .

. Emanation

orium A . . .

orium C . . .

β

α

. C

2

Mesothorium 1

Mesothorium 2

orium B . . .

orium D . . .

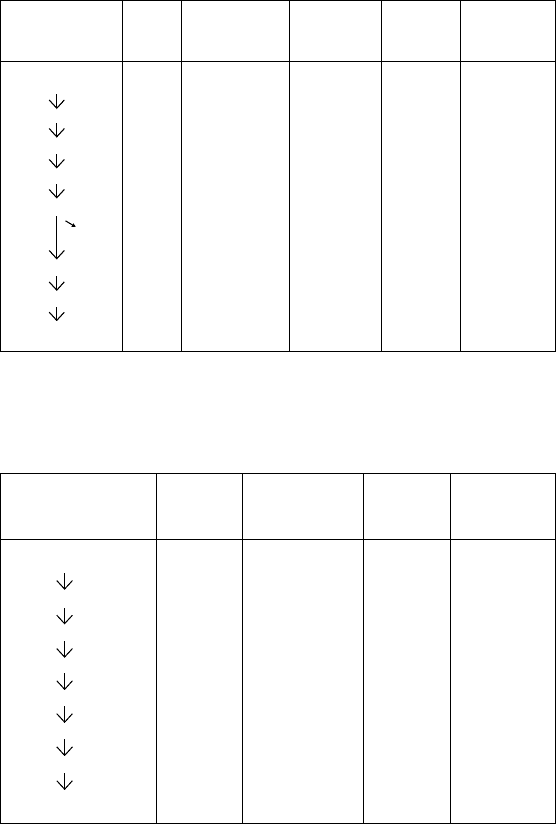

1. e Uranium Family

Radioelement and Rays

Half life

(years, days, hours, minutes, seconds)

Uranium I 4,500,000,000 y

↓ α

Uranium X

1

( orium 234) 24 d

↓ β

Uranium X

2

(Protactinium 234) 1.2 m

↓ β

The Radioactive Decay Series According to Modern Data

Source: From Ernest Rutherford, Radioactive Substances and their Radiations (Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press, 1913), 468, 518, 533, 552. Reproduced with permission of

Ernest Rutherford’s family.

(continued)

APPENDIX 2

220

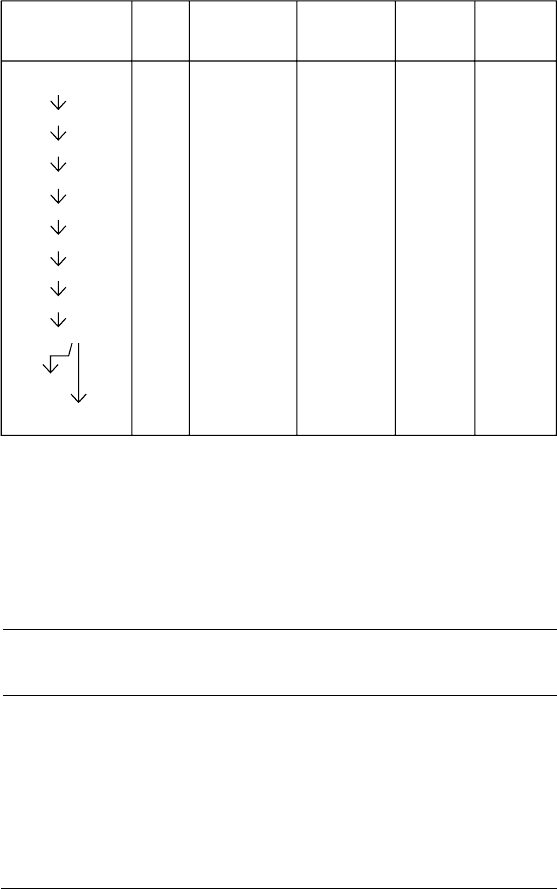

1. e Uranium Family—(continued)

Radioelement and Rays Half life

(years, days, hours, minutes, seconds)

Uranium II (Uranium 234) 240,000 y

↓α

Ionium ( orium 230) 77,000 y

↓ α

Radium (Radium 226) 1,600 y

↓ α

Radium emanation (Radon 222) 3.8 d

↓ α

Radium A (Polonium 218) 3.1 m

↓ α or ↘ β

Radium B

(Lead 214)

Astatine

(Astatine 218)

27 m, 2 s

↓ β ↙ α

Radium C (Bismuth 214) 20 m

↓ β or ↘ α

Radium C'

(Polonium 214)

Radium C”

( allium 210)

0.00016 s, 1.3 m

↓ α ↙ β

Radium D (Lead 210) 22 y

↓ β

Radium E (Bismuth 210) 5.0 d

↓ β or ↘ α

Radium F

(Polonium 210)

allium

( allium 206)

140 d, 4.2 m

↓ α ↙ β

Radium G (Lead 206) Not radioactive

FAMILY TREES FOR RADIOACTIVE ELEMENTS

221

2. e Actinium Family

Radioelement and Rays Half life

(years, days, hours, minutes, seconds)

Actinouranium (Uranium 235) 710,000,000 y

↓ α

Uranium Y ( orium 231) 26 h

↓ β

Protactinium (Protactinium 231) 33,000 y

↓ α

Actinium (Actinium 227) 22 y

↓ β or ↘ α

Radioactinium

( orium 227)

Actinium K

(Francium 223)

19 d, 22m

↓ α ↙ β

Actinium X (Radium 223) 11 d

↓ a

Actinium emanation (Radon 219) 4.0 s

↓ α

Actinium A (Polonium 215) 0.0018 s

↓ α or ↘ β

Actinium B

(Lead 211)

Astatine

(Astatine 215)

36 m, 0.0001 s

↓ β ↙ α

Actinium C (Bismuth 211)

2.1 m

↓ β ↘ α

Actinium C’

(Polonium 211)

Actinium C”

( allium 207)

0.005 s, 4.8 m

↓ α ↙ β

Actinium D (Lead 207) Not radioactive

APPENDIX 2

222

3. e orium Family

Radioelement and Rays Half life

(years, days, hours, minutes, seconds)

orium ( orium 232) 14,000,000,000 y

↓ α

Mesothorium I (Radium 228) 5.8 y

↓ β

Mesothorium II (Actinium 228) 6.1 h

↓ β

Radiothorium ( orium 228) 1.9 y

↓ α

orium X (Radium 224) 3.7 d

↓ α

orium emanation (Radon 220) 56 s

↓ α

orium A (Polonium 216) 0.15 s

↓ α or ↘ β

orium B

(Lead 212)

Astatine

(Astatine 216)

11 h, 0.0003 s

↓ β ↙ α

orium C (Bismuth 212) 61 m

↓ β or ↘ α

orium C'

(Polonium 212)

orium C”

( allium 208)

0.0000003 s, 3.1 m

↓ α ↙ β

orium D (Lead 208) Not radioactive

Sources: Samuel Glasstone, Sourcebook on Atomic Energy. Princeton, NJ: D. Van Nostrand,

1950.

Argonne National Laboratory, EVS, Human Health Fact Sheet. Argonne National

Laboratory (Illinois), 2005.

223

APPENDIX 3

Radioactivity’s Elusive Cause

From its discovery in 1896, radioactivity mysti ed researchers because they

could not nd an energy source for the exploding atoms. No ma er what sources

they tested and which novel methods they tried, they could not change the pro-

cess of radioactivity. ey failed because radioactive elements do not use energy

from outside themselves to disintegrate.

An atom needs energy in order to disintegrate. e energy that allows certain

atoms to spontaneously decay and release excess energy comes from inside these

atoms. Atoms of naturally radioactive heavy elements can disintegrate because

they are not stable. ey have a tendency to come apart because they contain large

numbers of mutually repelling positive charges (protons) within their nuclei.

e force that causes like charges to repel and unlike charges to a ract is

called the electrostatic force. e electrostatic force creates energy when charged

particles push themselves apart or pull themselves together. It takes a good deal

of energy to overcome the electrostatic forces inside heavy nuclei and keep the

protons from ying apart.

at energy comes from a force inside the nucleus called the strong force.

e strong force holds protons and neutrons together. If the strong force holding

these particles together is greater than the electrostatic force pushing the protons

apart, the nucleus will be stable.

If an unstable nucleus casts o an alpha particle, the new element formed may

send gamma rays out from its nucleus as it assumes a more stable con guration.

e gamma radiation represents the energy di erence between di erent energy

levels of the nucleus.

Researchers were puzzled to nd cases where alpha decay occurred even

though the electrostatic forces were slightly less than the strong forces within

a nucleus. ey could not understand how an alpha particle could escape the

nucleus if it did not have enough energy to overcome the forces that kept the pro-

tons and neutrons together. ese examples seemed to violate the conservation

of energy.

APPENDIX 3

224

A theory developed in the 1920s called wave mechanics showed that, although

high energy alpha particles are most likely to be able to escape a nucleus, even

low energy particles can do so. Whether or not a particular particle escapes is a

ma er of probability, and the probability for escaping never goes to zero. ese

probabilities, calculated by using wave mechanics, determine how long it takes,

on average, for atoms of a particular radioelement to decay. Some radioelements

have average lives of less than a second, while others have lifetimes of millions or

even billions of years.

In the 1930s physicists learned that neutrons themselves can disintegrate.

is process produces beta particles. e force involved in beta particle emission

was later named the weak force, in contrast to the strong force that holds nuclei

together. In beta decay a neutron transmutes into a proton, an electron (beta

particle), and an uncharged, nearly massless particle called an anti-neutrino.

Beta particle decay is also governed by laws of probability. A er a beta particle is

ejected, a new nucleus is formed, which may emit gamma rays.

During the rst years of radioactivity scientists believed that deterministic,

mechanical causes lay underneath the probabilistic equations that described

radioactivity. ey reasoned that although probability theory could describe

radioactivity, these abstract equations did not explain it. Radioactivity’s leaders

assumed that a mechanical cause or causes for radioactivity might be found in

the future.

A er quantum mechanics was developed and interpreted in terms of proba-

bilities, many scientists decided that the probabilistic equations were themselves

the explanation of radioactivity. ere was no deeper cause for the exploding

atoms. At the subatomic level, Nature was governed by Chance.

225

APPENDIX 4

Nobel Prize Winners Included

in This Book

Names are listed according to Nobel Lectures. Physics, 1901–1921; 1922–1941;

1942–1962; and Nobel Lectures. Chemistry, 1901–1921; 1922–1941; 1942–1962

(Amsterdam: Elsevier, 1964–).

Physics

1901 Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen

1902 Pieter Zeeman

1903 Antoine Henri Becquerel, Pierre Curie, and Marie Skłodowska-Curie

1904 Lord Rayleigh (John William Stru )

1905 Philipp Eduard Anton von Lenard

1906 Joseph John omson

1911 Wilhelm Wien

1913 Heike Kamerlingh Onnes

1914 Max von Laue

1915 William Henry Bragg and William Lawrence Bragg

1917 Charles Glover Barkla

1918 Max Planck

1919 Johannes Stark

1921 Albert Einstein

1922 Niels Bohr

1926 Jean Baptiste Perrin

1927 Charles omson Rees Wilson

1935 James Chadwick

1936 Victor Franz Hess

APPENDIX 4

226

Chemistry

1904 Sir William Ramsay

1908 Ernest Rutherford

1909 Wilhelm Ostwald

1911 Marie Skłodowska Curie

1914 eodore William Richards

1921 Frederick Soddy

1935 Jean Frédéric Joliot and Irène Joliot-Curie

1943 George de Hevesy (Georg von Hevesy)

1944 O o Hahn

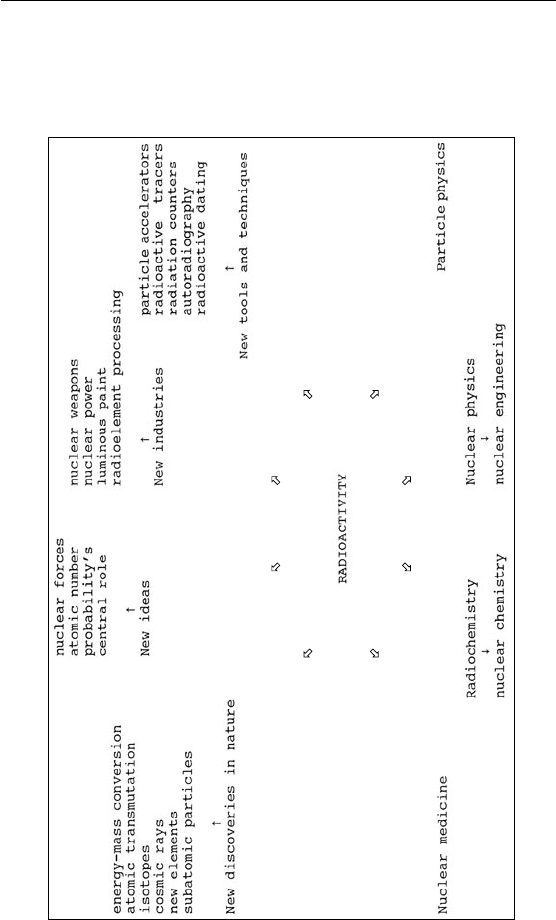

APPENDIX 5

Radioactivity’s Web of In uence

(Illustration by author)

227