Hoffman D.M., Singh B., Thomas J.H. (Eds). Handbook of Vacuum Science and Technology

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

796

Chapter 6.2: The Development of Ultra-High-Vacuum Technology

Rg.4.

10

c

o 4-i

o

x:

fc^

C/5

(L)

3

O

<D

-3

10

-4

10

10

-6

10

Aluminum

i

o—a--.QH

3

B

J

1 1

1

miir 1 1 Mini'

£^

"^N

1 1

iJiii'^

X.

ioJN

\

\

r 1 nir7i

VH2

CO

c

CH4

1 t 1 tun

10

17

18

1»

20 21

10

22

10 10 10 to

Dose (Photons/m)

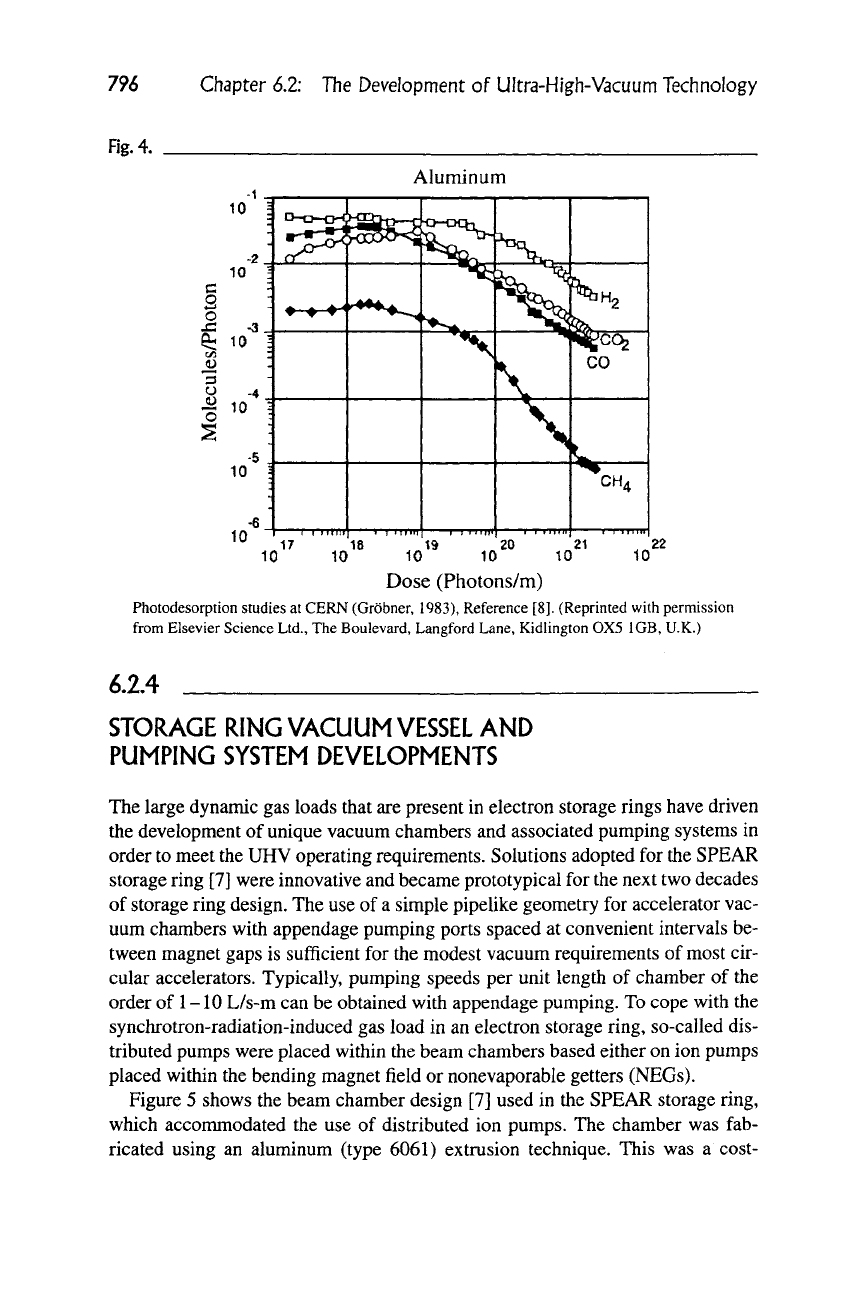

Photodesorption studies at CERN (Grobner, 1983), Reference [8]. (Reprinted with permission

from Elsevier Science Ltd., The Boulevard, Langford Lane, Kidlington 0X5 IGB, U.K.)

6.2.4

STORAGE RING VACUUM

VESSEL

AND

PUMPING SYSTEM DEVELOPMENTS

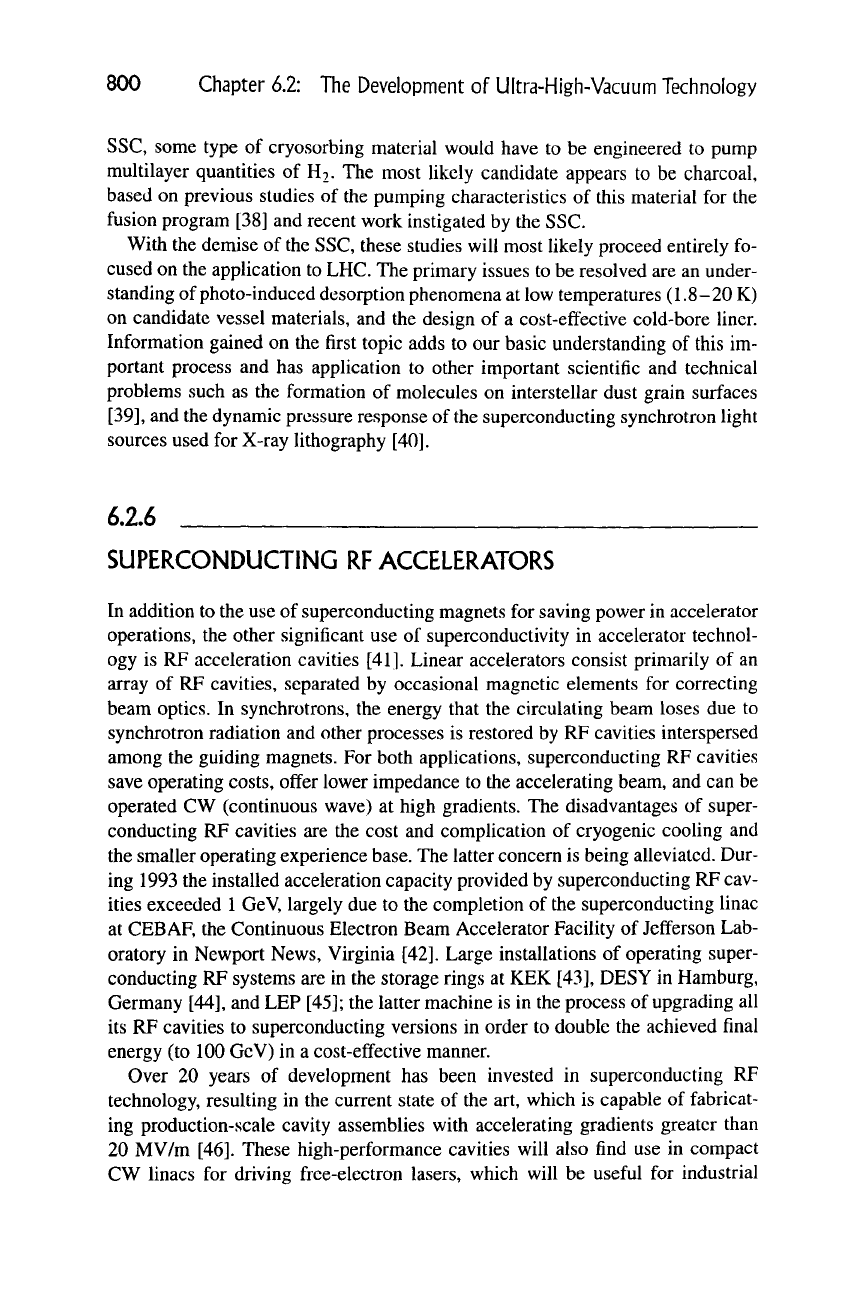

The large dynamic gas loads that are present in electron storage rings have driven

the development of unique vacuum chambers and associated pumping systems in

order to meet the UHV operating requirements. Solutions adopted for the SPEAR

storage ring [7] were innovative and became prototypical for the next two decades

of storage ring design. The use of a simple pipelike geometry for accelerator vac-

uum chambers with appendage pumping ports spaced at convenient intervals be-

tween magnet gaps is sufficient for the modest vacuum requirements of most cir-

cular accelerators. Typically, pumping speeds per unit length of chamber of the

order of 1-10 L/s-m can be obtained with appendage pumping. To cope with the

synchrotron-radiation-induced gas load in an electron storage ring, so-called dis-

tributed pumps were placed within the beam chambers based either on ion pumps

placed within the bending magnet field or nonevaporable getters (NEGs).

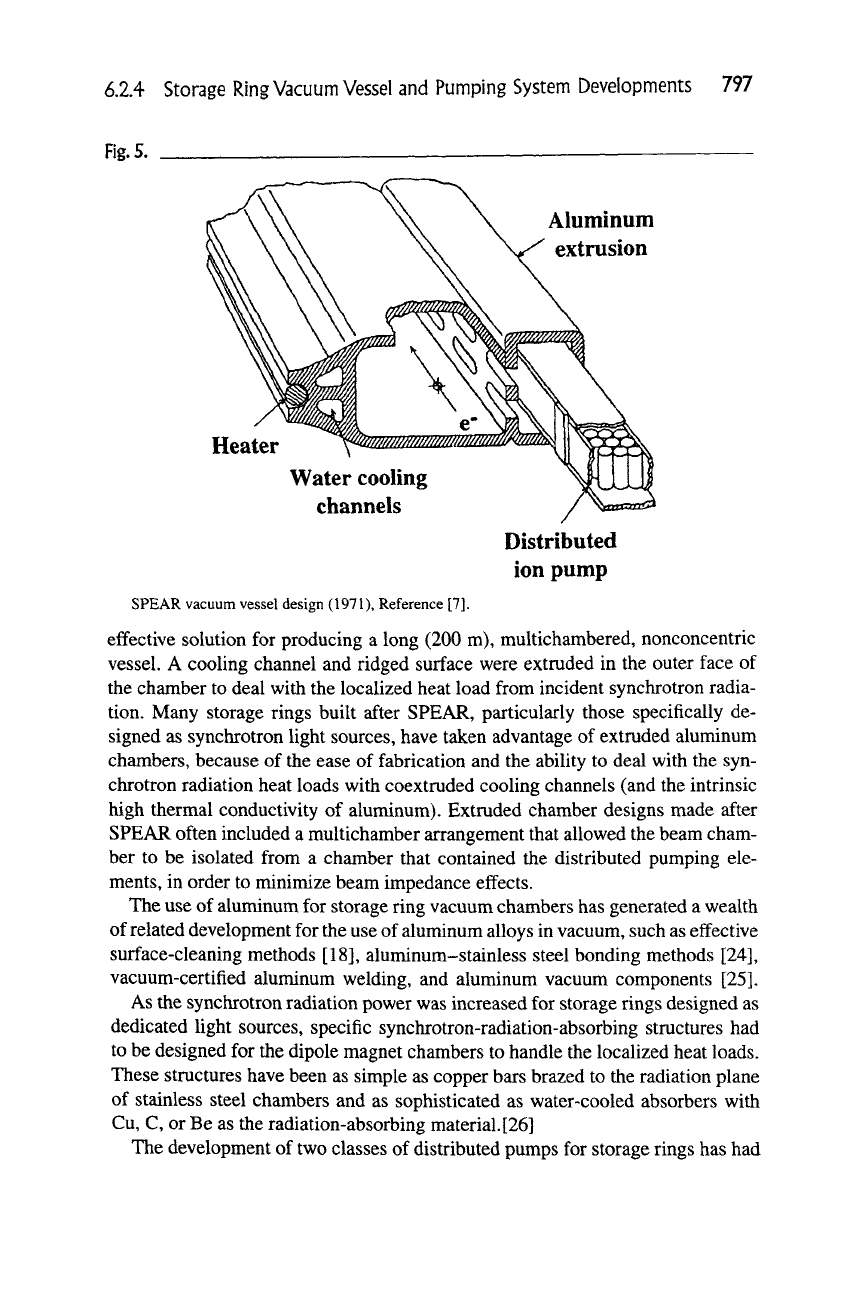

Figure 5 shows the beam chamber design [7] used in the SPEAR storage ring,

which accommodated the use of distributed ion pumps. The chamber was fab-

ricated using an aluminum (type 6061) extrusion technique. This was a cost-

6.2.4 Storage

Ring

Vacuum Vessel

and

Pumping System Developments

797

Fig.

5.

Aluminum

extrusion

Heater

Water cooling

channels

Distributed

ion pump

SPEAR vacuum vessel design (1971), Reference [7].

effective solution for producing a long (200 m), multichambered, nonconcentric

vessel. A cooling channel and ridged surface were extruded in the outer face of

the chamber to deal with the localized heat load from incident synchrotron radia-

tion. Many storage rings built after SPEAR, particularly those specifically de-

signed as synchrotron light sources, have taken advantage of extruded aluminum

chambers, because of the ease of fabrication and the ability to deal with the syn-

chrotron radiation heat loads with coextruded cooling channels (and the intrinsic

high thermal conductivity of aluminum). Extruded chamber designs made after

SPEAR often included a multichamber arrangement that allowed the beam cham-

ber to be isolated from a chamber that contained the distributed pumping ele-

ments, in order to minimize beam impedance effects.

The use of aluminum for storage ring vacuum chambers has generated a wealth

of related development for the use of aluminum alloys in vacuum, such as effective

surface-cleaning methods [18], aluminum-stainless steel bonding methods [24],

vacuum-certified aluminum welding, and aluminum vacuum components [25].

As the synchrotron radiation power was increased for storage rings designed as

dedicated light sources, specific synchrotron-radiation-absorbing structures had

to be designed for the dipole magnet chambers to handle the localized heat loads.

These structures have been as simple as copper bars brazed to the radiation plane

of stainless steel chambers and as sophisticated as water-cooled absorbers with

Cu, C, or Be as the radiation-absorbing material. [26]

The development of two classes of distributed pumps for storage rings has had

798 Chapter 6.2: The Development of Ultra-High-Vacuum Technology

a significant impact on the further development of both ion pumps and nonevap-

orable getters. The innovative use in SPEAR of the dipole magnet fields as the

confining field for ion pump Penning cells was an extension of the studies by

Schurrman [27] and originally Penning [28] of the magnetic field dependence of

cross-field gas discharges. Maler and Trachtenberg of Novosibirsk [29], and later

Hartwig and Kouptsidis of DESY [30], developed specific formulas applicable to

the design and performance of distributed ion pumps in both low- and high-field

situations.

For the 27-km Large Electron Positron (LEP) storage ring at CERN, a more

cost-effective distributed pumping scheme than in situ ion pumps was required.

LEP was the first to incorporate nonevaporable getter (NEG) pumps within the

vacuum chamber as the primary pumping element. An impressive quantity of de-

sign analysis and prototype testing of the selected NEG system (ZrAl alloy) was

performed by CERN under the direction of C. Benvenuti [31]. As a result, the

system has performed well since the startup of LEP in 1989. Numerous other

storage rings [32,33] had proceeded with incorporating NEGs as the distributed

pumping element even before LEP startup.

6.2.5

COLD-BORE MACHINES

What could very well be the last members of the family of colliders for high-

energy particle physics research are represented by the Superconducting Super

Collider (SSC) in the United States (which was canceled by U.S. Congress in

September 1993), and the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN (which is un-

der design and awaits construction approval by the CERN member nations). The

enormous cost for these machines (>

$1

IB for the SSC and > $4B for the LHC),

which is driven by their size and need for thousands of state-of-the-art supercon-

ducting magnets, often outweighs discussions of the scientific benefits.

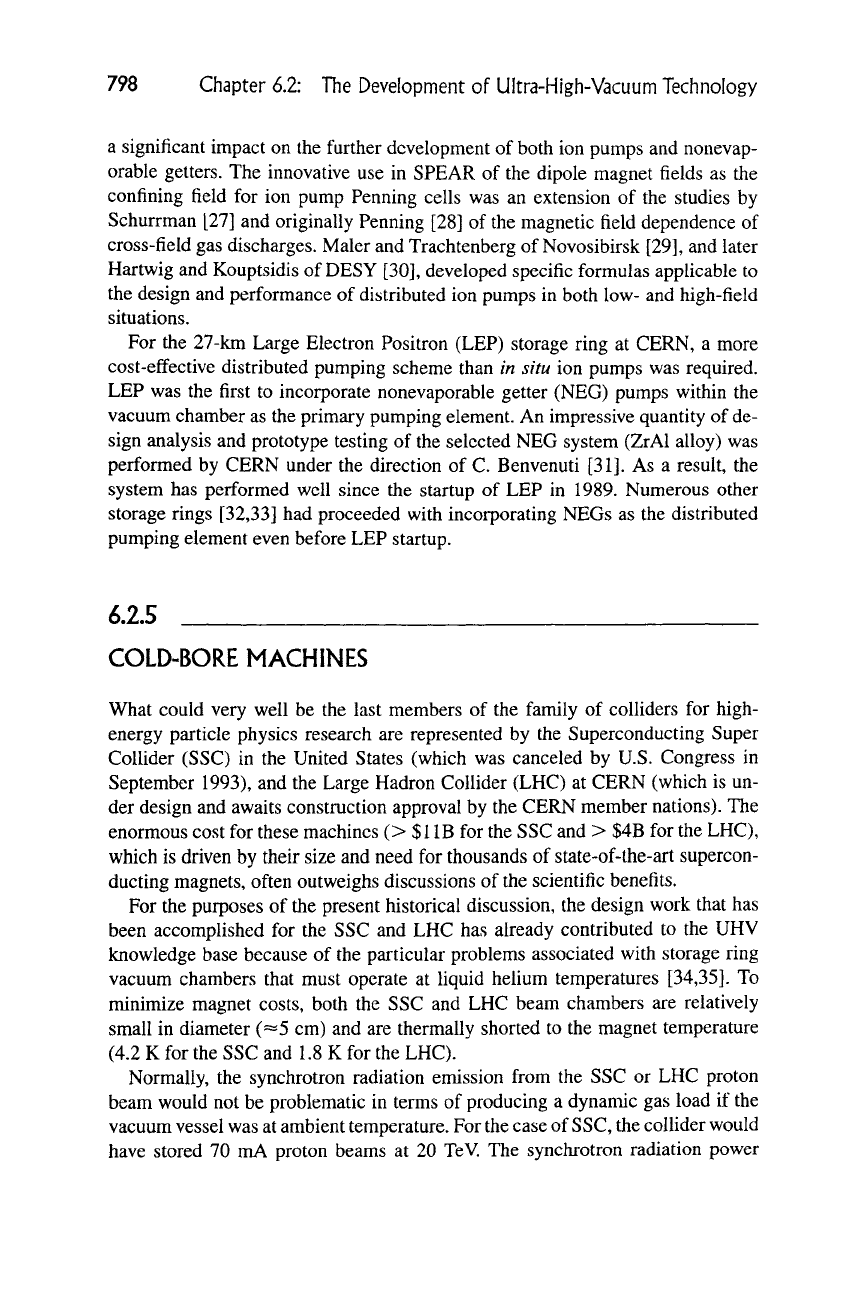

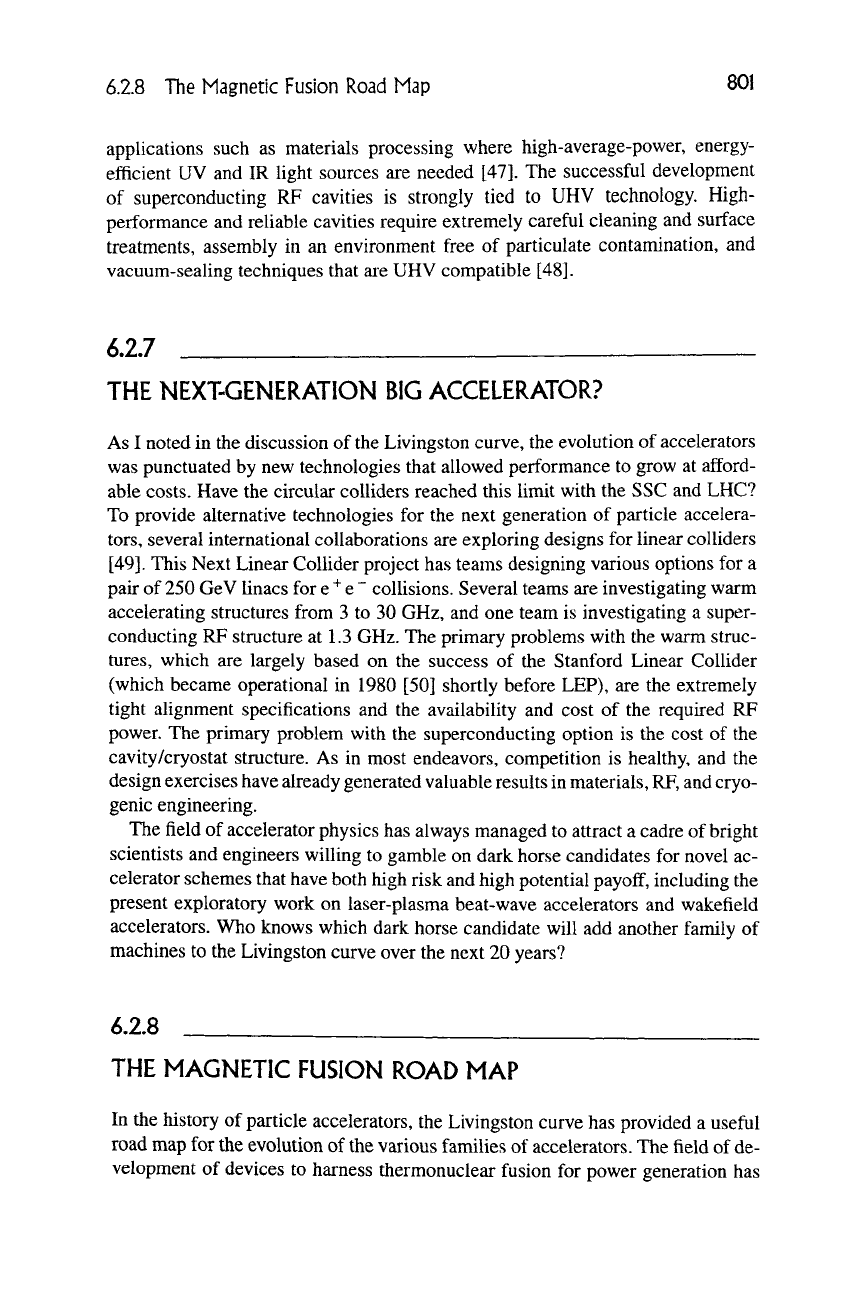

For the purposes of the present historical discussion, the design work that has

been accomplished for the SSC and LHC has already contributed to the UHV

knowledge base because of the particular problems associated with storage ring

vacuum chambers that must operate at liquid helium temperatures [34,35]. To

minimize magnet costs, both the SSC and LHC beam chambers are relatively

small in diameter (—5 cm) and are thermally shorted to the magnet temperature

(4.2 K for the SSC and 1.8 K for the LHC).

Normally, the synchrotron radiation emission from the SSC or LHC proton

beam would not be problematic in terms of producing a dynamic gas load if the

vacuum vessel was at ambient temperature. For the case of

SSC,

the collider would

have stored 70 mA proton beams at 20 TeV. The synchrotron radiation power

6.2.5 Cold-Bore Machines

799

onto the dipole magnet vacuum chambers is 0.14 W/m. The gas load desorbed

from such a radiation flux could be easily handled by the addition of modest dis-

tributed pumping as demonstrated in the electron rings. With ambient tempera-

ture surfaces, the photodesorbed gases will not be readsorbed on nearby surfaces

and would have a high probability of being removed from the gas phase by the

distributed pumps.

The case of photo-induced desorption and readsorption from surfaces near 4 K

is quite different. All the desorbed species of interest (CO, CO2, CH4 and H2O)

except for H2 are pumped well and have low equilibrium vapor pressures on 4 K

surfaces. Isotherm measurements on clean stainless steel at low temperatures

show that H2 is pumped and the H2 vapor pressure remains low (<10"^^ torr)

only if the H2 surface coverage remains below a monolayer [36,37]. Dynamic

pressures for the operation of both the SSC and LHC must remain below the

10 ~ ^^

torr range in order to prevent excessive beam scattering and excessive heat

load on the magnet cryostat as a result of the beam scattering. A proposed design

feature (Figure 6) within the cold-bore vacuum chambers to prevent the dynamic

pressure from exceeding the

10

" '^ torr limit is the incorporation of an intermedi-

ate temperature liner (@ —20 K) between the beam aperture and cold vessel wall.

This liner would intercept the synchrotron radiation and be partially slotted or

perforated to allow desorbed H2 molecules into the interspace. The 1.9 K operat-

ing temperature of the LHC cold bore is sufficiently low to pump H2 above mono-

layer quantities without exceeding the dynamic vacuum limits. However, for the

Fig.

6.

52 mm OD stainless

steel tube at 1.9 K

Cu-plated

stainless

Maximum induced

quench currents

He cooling ^^ ^

5-10

K

screen

LHC vacuum vessel design (1993), Reference

[35].

(©

1993

IEEE)

800 Chapter 6.2: The Development of Ultra-High-Vacuum Technology

SSC,

some type of cryosorbing material would have to be engineered to pump

multilayer quantities of H2. The most likely candidate appears to be charcoal,

based on previous studies of the pumping characteristics of this material for the

fusion program [38] and recent work instigated by the SSC.

With the demise of the SSC, these studies will most likely proceed entirely fo-

cused on the application to LUC. The primary issues to be resolved are an under-

standing of photo-induced desorption phenomena at low temperatures (1.8-20 K)

on candidate vessel materials, and the design of a cost-effective cold-bore liner.

Information gained on the first topic adds to our basic understanding of this im-

portant process and has application to other important scientific and technical

problems such as the formation of molecules on interstellar dust grain surfaces

[39],

and the dynamic pressure response of the superconducting synchrotron light

sources used for X-ray lithography [40].

6.2.6

SUPERCONDUCTING

RF

ACCELERATORS

In addition to the use of superconducting magnets for saving power in accelerator

operations, the other significant use of superconductivity in accelerator technol-

ogy is RF acceleration cavities [41]. Linear accelerators consist primarily of an

array of RF cavities, separated by occasional magnetic elements for correcting

beam optics. In synchrotrons, the energy that the circulating beam loses due to

synchrotron radiation and other processes is restored by RF cavities interspersed

among the guiding magnets. For both applications, superconducting RF cavities

save operating costs, offer lower impedance to the accelerating beam, and can be

operated CW (continuous wave) at high gradients. The disadvantages of super-

conducting RF cavities are the cost and complication of cryogenic cooling and

the smaller operating experience base. The latter concern is being alleviated. Dur-

ing 1993 the installed acceleration capacity provided by superconducting RF cav-

ities exceeded 1 GeV, largely due to the completion of the superconducting linac

at CEB

AF,

the Continuous Electron Beam Accelerator Facility of Jefferson Lab-

oratory in Newport News, Virginia [42]. Large installations of operating super-

conducting RF systems are in the storage rings at KEK [43], DESY in Hamburg,

Germany [44], and LEP [45]; the latter machine is in the process of upgrading all

its RF cavities to superconducting versions in order to double the achieved final

energy (to 100 GeV) in a cost-effective manner.

Over 20 years of development has been invested in superconducting RF

technology, resulting in the current state of the art, which is capable of fabricat-

ing production-scale cavity assemblies with accelerating gradients greater than

20 MV/m [46]. These high-performance cavities will also find use in compact

CW linacs for driving free-electron lasers, which will be useful for industrial

6.2.8 The Magnetic Fusion Road Map 801

applications such as materials processing where high-average-power, energy-

efficient UV and IR light sources are needed [47]. The successful development

of superconducting RF cavities is strongly tied to UHV technology. High-

performance and reliable cavities require extremely careful cleaning and surface

treatments, assembly in an environment free of particulate contamination, and

vacuum-sealing techniques that aie UHV compatible [48].

6.2.7

THE NEXT-GENERATION BIG ACCELERATOR?

As I noted in the discussion of the Livingston curve, the evolution of accelerators

was punctuated by new technologies that allowed performance to grow at afford-

able costs. Have the circular colliders reached this limit with the SSC and LHC?

To provide alternative technologies for the next generation of particle accelera-

tors,

several international collaborations are exploring designs for linear colliders

[49].

This Next Linear Collider project has teams designing various options for a

pair of 250 GeV linacs for e

"*'

e

~

collisions. Several teams are investigating warm

accelerating structures from 3 to 30 GHz, and one team is investigating a super-

conducting RF structure at 1.3 GHz. The primary problems with the warm struc-

tures,

which are largely based on the success of the Stanford Linear Collider

(which became operational in 1980 [50] shortly before LEP), are the extremely

tight alignment specifications and the availability and cost of the required RF

power. The primary problem with the superconducting option is the cost of the

cavity/cryostat structure. As in most endeavors, competition is healthy, and the

design exercises have akeady generated valuable results in materials,

RF,

and cryo-

genic engineering.

The field of accelerator physics has always managed to attract a cadre of bright

scientists and engineers willing to gamble on dark horse candidates for novel ac-

celerator schemes that have both high risk and high potential

payoff,

including the

present exploratory work on laser-plasma beat-wave accelerators and wakefield

accelerators. Who knows which dark horse candidate will add another family of

machines to the Livingston curve over the next 20 years?

6.2.8

THE MAGNETIC FUSION ROAD MAP

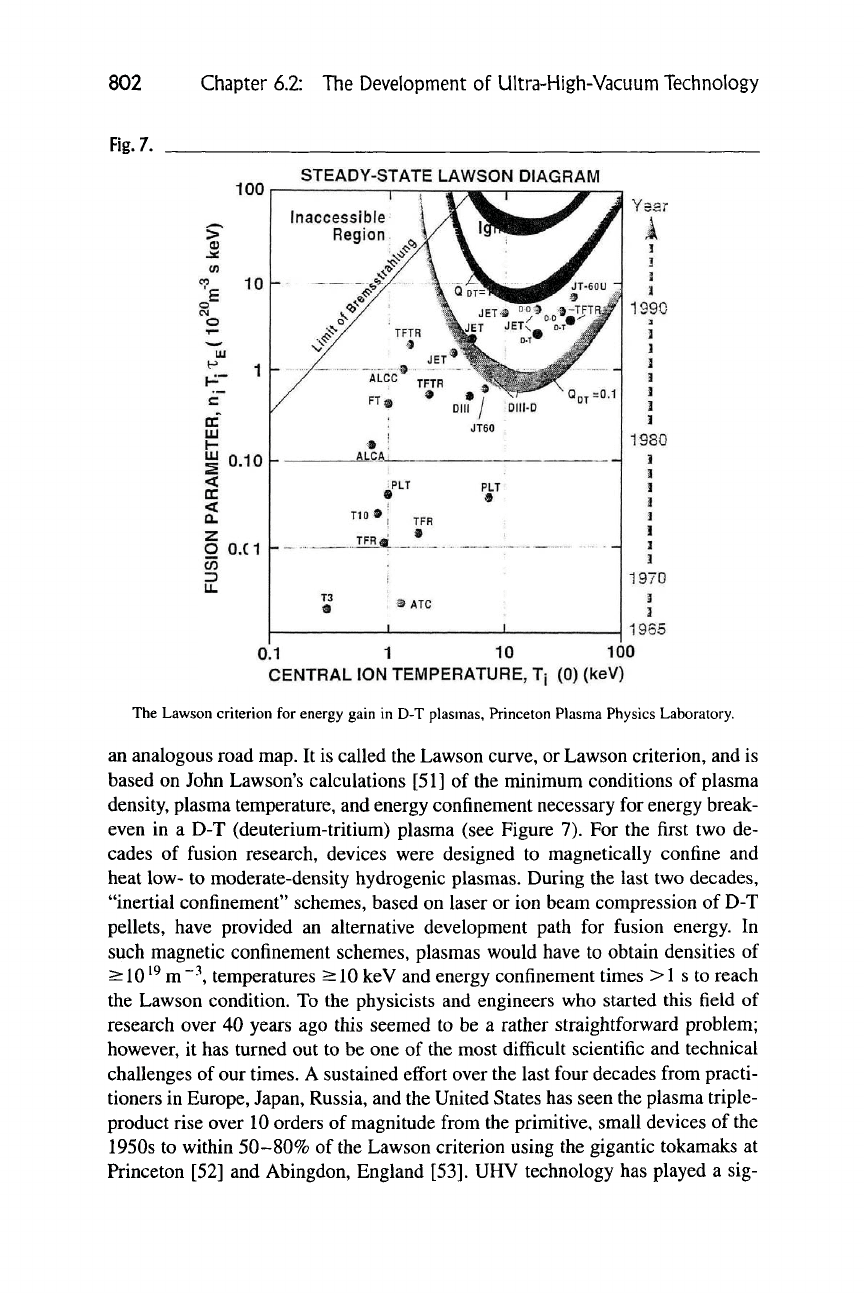

In the history of particle accelerators, the Livingston curve has provided a useful

road map for the evolution of the various families of accelerators. The field of de-

velopment of devices to harness thermonuclear fusion for power generation has

802 Chapter 6.2: The Development of Ultra-High-Vacuum Technology

Fig.

7.

>

0)

(0

m

'E

o

o

T—

UJ

h^"

c"

Q:

m

LU

s

<

cc

<

Q.

z

o

CO

3

u.

100

10

1

0.10

0.C1

STEADY-STATE LAWSON DIAGRAM

I ; 4 /^^ 1

inaccessible 1 y\ ^jj^^M

Region ^y \

'9^^^^

^JT-60U "

o^y^ \ JET* °°^.oV-!#

/ ALCC TFTR ^|MP

/ FT* • •7 ^^f^

/ "^'^ Dill / Dlll-D

JT60

#

;

ALCA_

^PLT PLT

• #

TIO • i TFR

TFR4 • „_ ;

;3 »ATC

1 1

QDT=0-1

-~ -

Year

A

1

3

]

1

199C

a

3

]

1

i

]

]

1980

]

1

i

1

1

3

1

1970

1

I

1965

0.1

10

100

CENTRAL ION TEIVIPERATURE, Tj (0) (keV)

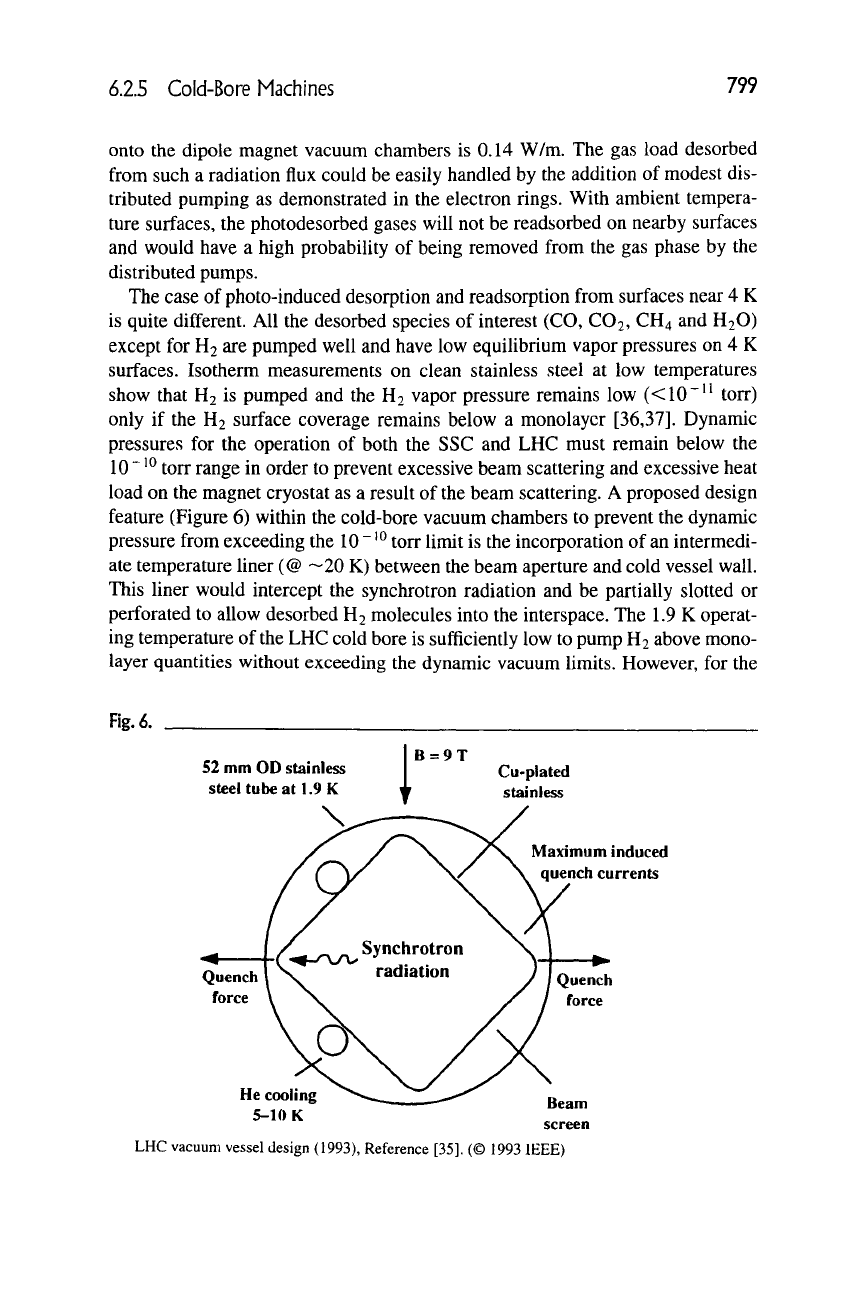

The Lawson criterion for energy gain in D-T plasmas, Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory.

an analogous road map. It is called the Lawson curve, or Lawson criterion, and is

based on John Lawson's calculations [51] of the minimum conditions of plasma

density, plasma temperature, and energy confinement necessary for energy break-

even in a D-T (deuterium-tritium) plasma (see Figure 7). For the first two de-

cades of fusion research, devices were designed to magnetically confine and

heat low- to moderate-density hydrogenic plasmas. During the last two decades,

"inertial confinement" schemes, based on laser or ion beam compression of D-T

pellets, have provided an alternative development path for fusion energy. In

such magnetic confinement schemes, plasmas would have to obtain densities of

>10^^

m~\ temperatures >10 keV and energy confinement times >1 s to reach

the Lawson condition. To the physicists and engineers who started this field of

research over 40 years ago this seemed to be a rather straightforward problem;

however, it has turned out to be one of the most difficult scientific and technical

challenges of our times. A sustained effort over the last four decades from practi-

tioners in Europe, Japan, Russia, and the United States has seen the plasma triple-

product rise over 10 orders of magnitude from the primitive, small devices of the

1950s to within 50-80% of the Lawson criterion using the gigantic tokamaks at

Princeton [52] and Abingdon, England [53]. UHV technology has played a sig-

6.2.9 The Early History of Magnetic Fusion 803

nificant role in the development of magnetic fusion devices. Before I cite specific

examples that are largely based on the developments on the last two decades,

it is informative to review the early history in the 1950-1960s, when the key

problems of magnetic fusion and high-temperature plasma research were being

defined.

6.2.9

THE EARLY HISTORY OF MAGNETIC FUSION

Fusion research has always had strong political overtones from its initiation in the

1950s through several large boom-or-bust cycles of government funding to its

present uncharted future. The possibilities of fusion power or "controlled ther-

monuclear reactors" were clearly in the minds of physicists who witnessed the

first man-made thermonuclear reactions with the explosion of the first D-T weap-

ons.

The first serious effort in the United States to launch a fusion research pro-

gram was initiated by an announcement in March 1951 by the Argentinean dic-

tator Juan Peron that his nation had haincssed fusion power with the help of an

exiled German scientist, Ronald Richter. The claim proved unfounded, but it

helped launch a secret program of fusion research that was code-named Project

Sherwood [54]. This program had proponents who championed three different

schemes for magnetically confining plasmas. Lyman Spitzer from Princeton Uni-

versity, who is generally given credit for having first elucidated the basic physics

of magnetic confinement, conceived of a figure-eight confinement geometry he

called a stellarator. A solenoidal field would confine the plasma, an inductively

driven current would heat the plasma, and the twist in the field geometry would

compensate for the tendency for charged particles to drift out of a simple torus.

James Tuck, a British physicist on loan to the Manhattan project during World

War II, had returned to Los Alamos with a scheme he developed with his col-

leagues at Oxford to confine and heat plasmas in a sample focus by "pinching"

the plasma to a small radius stream by rapidly increasing the toroidal field. Tuck

had a more sanguine view of the probable vicissitudes of confined plasmas and

named his device the Perhapsatron. A third team, led by Richard F. Post and

Herbert York, at the Livermore branch of the University of California's Radiation

Lab (the ancestor of the Lawrence Livermore Laboratory), proposed an open so-

lenoidal confinement scheme they termed "mirror machines."

All the early schemes were fraught with difficulties: the plasma confinement

appeared poor, plasma temperatures were low, and the primitive vacuum technol-

ogy that was used guaranteed that the plasma species of interest was overwhelmed

by impurities from the confining chamber walls. Adding to the difficulties were

the poor state of developed instrumentation to measure plasma properties and a

primitive level of theoretical understanding of this complicated multicomponent

804 Chapter 6.2: The Development of Ultra-High-Vacuum Technology

fluid system. The situation took on a decidedly different perspective and pace

vv^hen the secret Project Sherwood was declassified in 1958 on the eve of the fa-

mous Atoms for Peace Conference in Geneva. At this time it became clear that

the ambitious Russian program had not progressed significantly ahead of the

Western efforts. The claims of near success had once again been heralded, this

time by the British with their Zeta model of a plasma pinch in 1957, but by the

time of the Geneva Conference the neutrons observed in the Zeta experiments

were shown to be not thermonuclear in origin [55]. A growing realization of the

difficulty of the confinement problem, the embarrassment of the false claims of

success, and the visibility engendered by the program declassification forced the

fusion research to a more balanced mix of theory, machine, and measurement.

6.2.10

MODEL CTHE FIRST UHV FUSION DEVICE

When Spitzer had conceived the stellarator concept, he developed a plan for mov-

ing the technology along an orderly route from the pioneering Model A, which

was a table-top demonstration, to a larger Model B, designed to push the plasma

parameters, to an engineering prototype (Model C), which would be a scale model

reactor, to finally a full-scale prototype reactor (Model D) [56]. A remarkable

document, completed by Spitzer's team in 1954, actually spells out many of the

important subsystems that a fusion reactor would require: an auxiliary heating

system to reach plasma ignition temperatures, a magnetic "diverter" to remove

plasma impurities, and a lithium blanket for absorbing the fusion product neu-

trons and extracting energy from the reactor. The disappointing results coming in

from the experiments on the B-series of stellarators, and similar results from the

plasma pinch and mirrors programs, considerably stretched out Spitzer's develop-

ment plan for a reactor. Model C would not be a scale model reactor—it would

be the next step in elucidating the plasma physics. However, Model C would rep-

resent the largest single investment ($35M) in the program to date, and for the

first time industrial contractors would participate in the design and construction

of the machine. The Model C stellarator came to life in 1961. Its stainless steel

vacuum vessel was the largest UHV system built to date [5]. Special double-joint,

gold wire flange seals allowed the system to be baked to 450°C. After bakeout,

base pressures for the system were in the

10 ~^^

ton* range. Because of the con-

cerns for hydrocarbon contamination, the Model C was pumped with two large

mercury diffusion pumps that were isolated from the torus by lead-sealed valves

and freon-cooled traps. Mercury was chosen as the pumping fluid because its

accidental presence in the torus vacuum could be detected very sensitively by

plasma spectroscopic techniques, and the high-temperature vessel bakeout would

easily remove the contamination. The performance of the Model C vacuum sys-

6.2.11

The

Russian Revolution

in

Fusion:

Tokamaks

805

tern was a huge success —

the

plasma performance, on the other hand, was dis-

appointing.

For most of the 1960s none of three confinement schemes being pursued in the

United States or United Kingdom were making any significant progress toward

the Holy Grail represented by the Lawson criterion. The knowledge base on fully

ionized plasmas was expanding at a healthy rate fed by careful measurements

with new plasma "diagnostic" instruments and increasingly sophisticated plasma

theory. Despite these advances, by the end of the 1960s neither the measurements

nor the theory could tell the experimenters why their plasmas remained relatively

poorly confined and cold [57].

6.2.11

THE RUSSIAN REVOLUTION IN

FUSION:

TOKAMAKS

As the 1960s drew to a close, a pair of closely coupled political events caused a

dramatic change in the pace of fusion development. The cold war prevented any

significant exchange of information between the Western and Soviet programs

except for brief interactions at plasma physics conferences organized by the In-

ternational Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). At the 1965 [58] and 1969 [59] con-

ferences, the Russians claimed that their toroidal magnetic chamber or "tokamak"

geometry was producing plasmas with confinement times of milliseconds and

plasma temperatures near a kilovolt. These results were met with skepticism, be-

cause they represented at least two orders of magnitude improvement over the

best results from the competing Western devices. The skepticism faded in 1969

when a thaw in cold war relations allowed the leader of the fusion effort at the

Kurchatov Institute in Moscow, Lev Arsimovitch, to come to MIT for a lecture on

disarmament issues. An impromptu series of lectures on the results from the Kur-

chatov T-3 tokamak began to convince a steady stream of American plasma

physicists that traveled to Cambridge to hear and question Arsimovitch. The last

doubts disappeared when a team of British physicists visiting the Kurchatov In-

stitute cabled to Washington that they had confirmed the T-3 results with laser

scattering measurements of plasma temperature and density made with equip-

ment they had imported from their laboratory at Culham [59].

The tokamak race was on. Tokamaks were under construction at Oak Ridge

[60],

MIT [61], and the General Atomics Co. [62] in San Diego. The Model C

stellarator at Princeton was converted to a tokamak in four months, and in the first

two months of operation reconfirmed the confinement properties and stability

limits of the tokamak geometry. Moreover, the confinement properties appeared

to possess a favorable scaling with size: The energy confinement time would im-

prove with the square of plasma radius. Plans were quickly drawn up for a second

generation of tokamaks by scaling up a factor of 2 in size, followed by another