Gardiner V., Matthews H. The changing geography of the United Kingdom

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

JONATHAN HORNER

386

For this reason, pollution monitoring and control need to be on an international rather than

on a national scale. This is also sensible in view of the fact that pollutants tend to be emitted

from large numbers of globally dispersed sources. In the 1990s there is therefore increasing

emphasis on regional and global aspects of pollution and a growing influence of international

regulations on controlling pollution in the United Kingdom. The changing geography of

UK pollution will therefore be examined in the context of international developments in

pollution control before recent national progress is considered.

As the serious and wide-ranging nature of environmental pollution problems has

become more evident, so has the need for greater international co-operation to develop

effective pollution control policies. International agreements have recently been forged

to control a number of important pollutants. For example, at the June 1992 United Nations

Conference on Environment and Development (‘The Earth Summit’ held in Rio de Janeiro)

delegates from many countries signed the Framework Convention on Climate Change,

and over 160 countries have now signed. The ultimate objective of the Convention is to

stabilise ‘greenhouse gas’ concentrations at levels that will prevent anthropogenic influence

on the climate system. The 1986 Montreal Protocol, subsequently amended at meetings

of the countries involved (the ninth meeting taking place in 1997) to bring in more stringent

controls, agreed international action to reduce emissions of ozone (O

3

) depleting chemicals.

The United Kingdom is committed under a United Nations Economic Commission for

Europe (UNECE) Protocol to reduce emissions of volatile organic compounds (VOCs)

by 30 per cent between 1988 and 1999 with the aim of reducing tropospheric ozone

concentrations (Great Britain 1996). In 1994 the government signed an international

protocol committing the UK to reducing sulphur dioxide (SO

2

) emissions from all sources

by 80 per cent by 2010 compared with 1980 levels (Great Britain 1996). These major air

pollutants all present serious environmental threats and will be considered in more detail

in the next section.

In the 1990s, the European Union (EU) has been increasingly influencing pollution

control policies in member states. In July 1987, the Single European Act came into force

and called for unified environmental standards and pollution prevention measures. EU

Directives have, for example, set air-quality standards for sulphur dioxide (SO

2

), smoke,

nitrogen dioxide (NO

2

), lead and ozone. They have also required licensing systems for

waste management and disposal operations, and have set water-quality standards for bathing

and drinking water. These Directives are binding on member states, although each country

is free to devise its own methods to achieve the standards—usually by a specified date. The

European Environment Agency (EEA) began operating in October 1994 and acts to integrate

environmental protection and improvement information in Europe. In August 1995, the

EEA published the most detailed and comprehensive review available of the state of the

environment in Europe—Europe’s Environment—The Dobris Assessment (Stanners and

Bourdeau 1995). The report highlighted twelve ‘prominent European environmental

problems’, which are listed in Table 18.1. Examination of these shows that they are all

either specifically pollution problems or include pollutants as contributing factors to the

problem. These prominent environmental problems will be used as a focus for discussion

and for selecting atmospheric, terrestrial and aquatic pollutants for consideration in the

following sections of this chapter.

During the 1990s, there have been some significant changes in the organisational

structure for controlling pollution in the United Kingdom. The 1990 Environmental Protection

POLLUTION

387

Act introduced Integrated Pollution Control (IPC), a system which requires a single

authorisation to be obtained for polluting processes which encompasses atmospheric,

terrestrial and aquatic pollution. Authorisation is based on the Best Available

Technology Not Entailing Excessive Cost (BATNEEC) being used to control emissions.

On 1 April 1996, the Environment Agency for England and Wales took up its statutory

duties in this respect, bringing together functions previously conducted by Her

Majesty’s Inspectorate of Pollution (for air pollution), the National Rivers Authority

(for water pollution) and the sections in local and central government dealing with

waste regulation and contaminated land (for terrestrial pollution and waste disposal).

Legal structures in Scotland and Northern Ireland differ from those in England and

Wales, and the Scottish and Northern Ireland Offices have their own Environment

Departments.

In 1990, the UK government published its first White Paper on the environment (Great

Britain 1990), which has been followed by annual reviews. The major UK political parties

have paid more attention to environmental issues in recent years and the apparent commitment

by consecutive governments to improving environmental performance and to reducing

environmental pollution is possibly a major cause of the relative demise of the Green Party.

Having received 15 per cent of votes cast in the European parliament elections in June

1989, the Green Party saw its share of the vote cut to less than 2 per cent in the May 1997

General Election. However, whilst the Labour Party’s 1997 manifesto included many

environmental proposals, environmental groups have expressed concern that the Queen’s

Speech for the opening of parliament referred to few of the proposals.

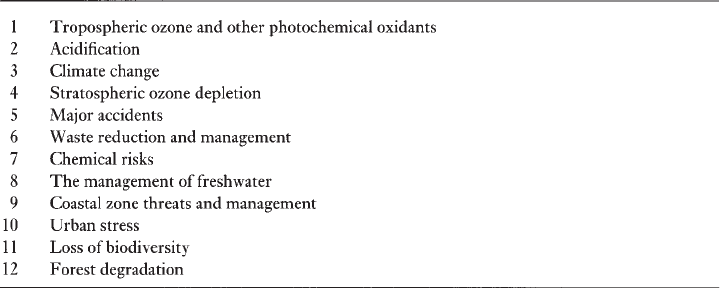

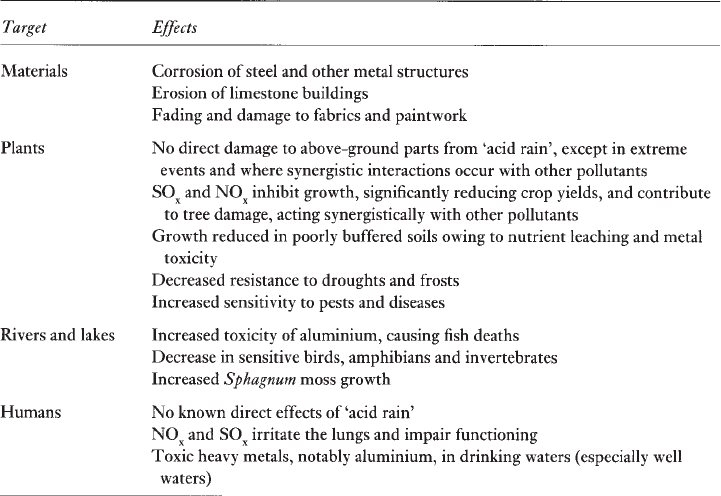

TABLE 18.1 Twelve ‘prominent European environmental problems’ identified by the Dobris Assessment

Source: Stanners and Bourdeau (1995).

Note: The Dobris Assessment was produced in response to the First European Environment Minister

Conference held at Dobris Castle near Prague in June 1991 and reinforces concerns raised at the

conference. It was organised by Josef Varousek, First Minister of the Environment of Czechoslovakia

(today split into the Czech and Slovak Republics), and attended by Ministers or their deputies from

almost all European countries. The report covers the state of the environment in nearly fifty countries,

presenting data (including data on pollution), and identifies a number of serious environmental threats.

It confirms poor environmental quality in many parts of Europe, often caused by the emission of

pollutants. The twelve problems listed above were identified as the twelve most pressing environmental

problems currently facing European countries.

JONATHAN HORNER

388

Increasingly, companies are paying more attention to environmental issues and making

attempts to reduce emissions of pollutants. As Porritt (1991) pointed out:

in contrast to the kind of green public relations and promotional gimmicks which we

saw so much of in the mid 1980s, businesses are now genuinely working to clean up

their act.

(Porritt 1991:193)

In the UK, the Advisory Committee on Business and the Environment was jointly established

by the Department of Trade and Industry and the Department of the Environment in 1991.

It provides advice on environmental policy issues and encourages dialogue between

government and business on environmental matters. Leading companies have adopted

environmental policies which aim to improve environmental performance, for example by

reducing emissions of pollutants. The policies are implemented by establishing environmental

management systems which can be subjected to environmental auditing. This has enabled

companies to adopt a more proactive approach to pollution control compared with the more

reactive approach generally adopted in the 1980s. Companies are increasingly recognising

that risks and liabilities associated with pollution can translate into a tarnished public image,

legal costs and loss of competitive advantage. In 1995, the first registrations of UK companies

under BS 7750 (a UK-developed environmental management system) and the EU Eco-

Management and Audit Scheme took place. In 1997, thirty UK companies in the Financial

Times Top 100 companies published annual environmental reports separate from their annual

accounts, compared with twenty companies in 1993. In 1997, fourteen of the companies set

quantifiable targets, whilst none did so in 1993 (KPMG 1997).

Whilst it would be generally true to state that increasing concerns for environmental

quality, and improvements in pollution control, referred to by the Environment Agency in

this chapter’s opening quotes, have continued in the United Kingdom in the 1990s, there

are certainly exceptions to this. UK government figures show that during this decade

complaints about noise pollution have increased, that the amount of derelict land (which is

often polluted) in the South East has increased, and that there have been some falls in

compliance with EC Bathing Water Directives in the Northumbrian, Southern and South

West Water Regions (DETR 1997). The Environment Agency (1997) showed that there was

a steady rise in reported water pollution incidents in England and Wales during the first half

of this decade. However, it should be borne in mind that increases in reported incidents or

complaints of pollution could arise from increased awareness and tendency to complain

about it. The following sections examine recent changes in UK atmospheric, terrestrial and

aquatic pollution, respectively.

Atmospheric pollution

UK improvements in industrial pollution control and reductions in emissions from domestic

sources, to a great extent initiated by the Clean Air Acts of 1956 and 1968, have continued

during the 1990s as further legislation has been introduced. However, an increasing number

of motor vehicles on UK roads, reported in Chapter 6, has led to this source of emissions

becoming increasingly significant in contributing to the changing patterns of UK air pollution.

More effort to control motor vehicle emissions, or to reduce the UK’s reliance on motor

POLLUTION

389

cars, is clearly needed if motor vehicles are not to be an increasingly significant pollution

source in the next millennium. Pollutants, notably smoke and SO

2

, previously monitored to

measure overall air quality, have declined in concentrations, particularly in urban areas.

However, they have been replaced by increasing concentrations of some other air pollutants,

notably by O

3

and VOCs, sometimes in rural areas. This will now be explained, starting

with air pollutants of more local concern and then moving on to consider pollutants which

are more of an international problem.

Smoke and SO

2

have been the traditional indicators of air quality in the UK. These

pollutants were largely responsible for infamous urban smogs, most notably the so-called

Great London Smog of 1952 which was estimated to have caused 4,000 premature deaths

during a five-day period in December 1952. They also cause damage to vegetation, reducing

crop yields, and to buildings, corroding metal and soiling brickwork. A general decline in

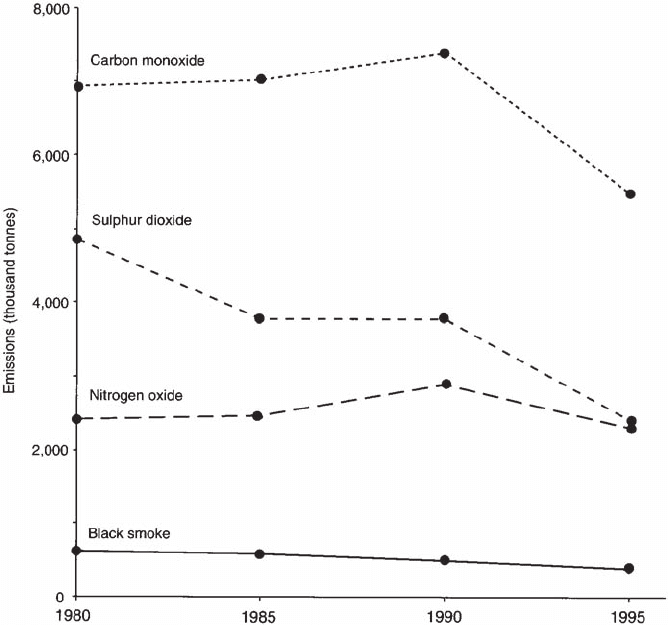

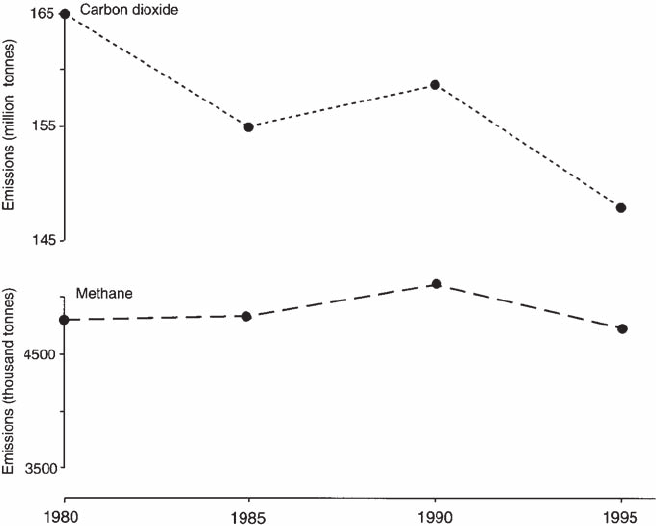

emissions of these pollutants has continued during the first part of the 1990s (Figure 18.2).

Between 1980 and 1995, emissions of SO

2

, about three-quarters of which come from large

combustion plants (LCPs), declined by 52 per cent. Over the same period black smoke

emissions, of which diesel engine vehicles have become the major emission source, declined

by 40 per cent. Black smoke emissions from domestic sources decreased by 79 per cent

FIGURE 18.2 Total UK emissions of selected local air pollutants, for the period 1980–95

Source: DETR (1997).

JONATHAN HORNER

390

during this period, reflecting increasing use of gas rather than coal for heating and further

introductions of smoke control areas. The EC LCP Directive required the UK, taking 1980

as the baseline, to have reduced emissions of SO

2

from LCPs by 20 per cent by the end of

1993, by 40 per cent by the end of 1998 and by 60 per cent by the end of 2003. The latter

target is already close to being attained, with recent reductions having been achieved by

commissioning new gas-burning power stations. However, with natural gas supplies in

relatively short supply it might be difficult to maintain this reduction as the next millennium

progresses.

With declining UK concentrations of smoke and SO

2

, increasing attention has been

paid to other air pollutants. The recent Dobris Assessment, referred to in the previous section

of this chapter, identified four problems in its list of twelve ‘prominent European

environmental problems’ which are specifically caused by atmospheric pollutants. These

are ‘tropospheric O

3

and other photochemical oxidants’, ‘acidification’, ‘climate change’

and ‘stratospheric O

3

depletion’; each will be considered in turn. Other problems identified,

notably ‘urban stress’ caused partly by motor vehicle emissions, ‘major accidents’, ‘forest

degradation’ and ‘chemical risks’ also have atmospheric pollutants as major contributing

causes or as being the cause of resulting effects. There have been increasing episodes of

poor urban air quality, characterised by elevated concentrations of nitrogen oxides (NO

x

),

CO and VOCs, and of tropospheric O

3

formation, both of which are largely caused by

motor vehicle emissions. These pollutants are now more appropriate than black smoke and

SO2 as indicators of air quality. Concentrations of NO and CO shown in Figure 18.2, each

of which is emitted in significant quantities by motor vehicles, have declined to a much

lesser extent between 1980 and 1995 compared with black smoke and SO

2

. During this

period total NO

x

emissions, for which road transport is now responsible for about half of

total emissions, decreased by just 5 per cent. Oxides of nitrogen irritate the respiratory tract

(for example triggering asthma attacks), cause damage to vegetation (reducing crop yields)

and contribute to photochemical smog and acid rain formation. The EC LCP Directive

required the UK to reduce NO

x

emissions from LCPs, taking 1980 as the baseline, by 15 per

cent by 1993 and by 30 per cent by 1998. The latter target had already been achieved by

1995, with a 45 per cent reduction. However, the decrease in emissions from LCPs during

this period was almost matched by an increase in emissions from other sources, notably

road transport.

Carbon monoxide emissions, for which road transport now accounts for about three-

quarters of total emissions, decreased by 21 per cent, and ‘VOC’ emissions, which almost

exactly matched NO

x

emissions, declined by just 3 per cent between 1980 and 1995. Carbon

monoxide emissions are only a health threat in poorly ventilated confined situations, as

reviewed by Horner (1998). This invisible and odourless gas preferentially binds with

haemoglobin in the red blood corpuscles, reducing the amount of oxygen which can be

transported. Road transport accounts for about 30 per cent of total VOC emissions, the

remainder coming from solvent use and industrial processes. VOCs contribute to

photochemical smog formation and some are known carcinogens. The decline in CO and

VOC emissions has been partly due to increasing numbers of diesel cars on the road which

emit less of these pollutants than do petrol-engined vehicles. Increasing use of catalytic

converters on petrol-engined vehicles has also reduced emissions. However, diesel-powered

vehicles have been linked with emissions of carcinogenic organic compounds, so increasing

use of diesel-engined vehicles in the UK should be carefully considered.

POLLUTION

391

Emissions of lead from petrol-engined vehicles have declined substantially with the

reduction in lead content of petrol and the increasing use of unleaded petrol. Unleaded

petrol, which first appeared in the UK in 1987, accounted for 69 per cent of total UK petrol

consumption by the end of 1996 and total lead emissions from motor cars dropped from

7,500 tonnes in 1980 to just 1,000 tonnes in 1996 (DETR 1997). Of greater concern in the

1990s is the need to consider hazards from lead in old water pipes and old paint work. For

example, Horner (1996) reported lead concentrations in paint from surfaces in an old school

to be well in excess of the 5,000 ppm safety level recommended by the World Health

Organisation. Lead is a proven neurotoxin and has been shown to reduce IQ levels in children.

Whilst smogs caused by smoke and SO

2

are largely a thing of the past in the UK, they

have been replaced by photochemical smogs. The formation of such smogs, largely from

reactions between vehicle-emitted NO

x

and VOCs, has been of increasing concern in the

1990s. Hospital admissions in London have increased after surges in pollution levels.

Photochemical smogs are characterised by increased concentrations of tropospheric O

3

during

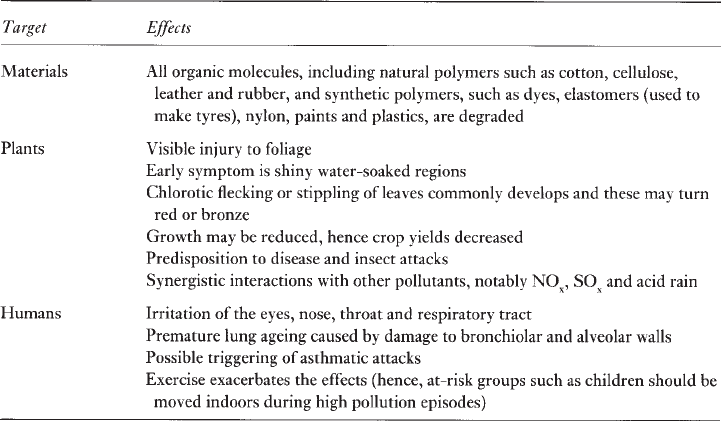

the summer, the effects of which are summarised in Table 18.2. No other compound has

atmospheric levels so close to toxic levels as commonly as O

3

. Ozone generating reactions

require sunlight and take some time to occur. This is one reason why highest O

3

concentrations

are often found in rural areas several hundred kilometres downwind from emission sources.

Concentrations of O

3

exceed thresholds for effects on vegetation and human health throughout

the UK. The largest and most frequent exceedences occur in southern England, especially

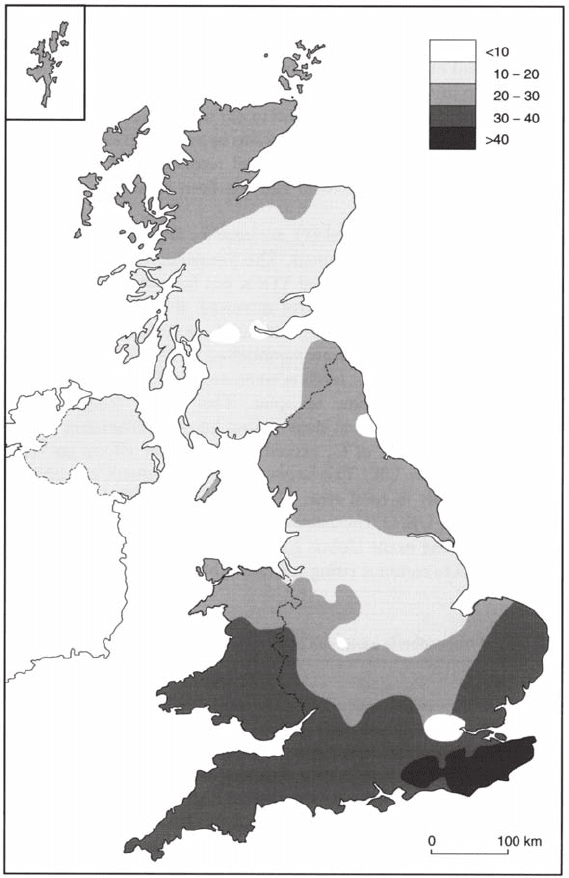

in rural areas of the South East (PORG 1997). Figure 18.3 shows the extent to which UK O

3

concentrations exceeded recommended safety levels for the years 1990–5. According to the

Dobris Assessment, O

3

concentrations in the northern hemisphere are expected to continue

rising at a rate of between 0.5 and 1 per cent a year.

TABLE 18.2 Effects of tropospheric ozone and other photochemical pollutants

JONATHAN HORNER

392

The role of NO

x

in forming ‘acid rain’ and the problems which this phenomenon

causes were widely reported in the 1980s. Sulphur oxides (SO

x

) and NO

x

, mainly from the

burning of fossil fuels, react in the atmosphere to form sulphuric and nitric acids. Some of

the major effects of acid deposition are summarised in Table 18.3. Widespread damage to

European forests has been caused, including in the UK, and serious damage to lakes in

FIGURE 18.3 UK tropospheric ozone levels, showing the number of days with eight-hour periods of

ozone exceeding fifty parts per billion, for the period 1990–5

Source: DETR (1997).

POLLUTION

393

Scandinavia, Scotland and north-west England has occurred, with major conservation

implications (see Chapter 20). It is important to distinguish between dry deposition of

the primary gaseous pollutants, which tend to have more local effects, and wet deposition

of the acids (‘acid rain’), which may be transported for several thousand miles before

being deposited. The concept of ‘critical loads’ has been used increasingly in the UK in

terms of predicting and controlling damage from acid deposition. A critical load is the

estimated load of deposition for a specified location, below which no harmful effects

are predicted. By comparing with actual deposition, critical load exceedences can be

predicted for UK soils and fresh waters. For soils, 32 per cent, and for fresh waters 17

per cent, of the area of the UK exceeded the estimated critical load for total acidity in

the period 1989–92 (DoE 1996). The most vulnerable areas are the uplands of north

and west Britain. Acidification of soils and freshwaters can create nutrient deficiency

and metal toxicity problems, hence limiting the range of sensitive fauna and flora. Based

on the apparent frequency of UK reporting, concern about acid deposition would appear

to have diminished in the 1990s. This partly reflects the fact that wealthier countries

like the UK, where damage was largely reported in the 1980s, have begun to introduce

emission control measures. In the UK several power stations, including the largest coal-

burning station at Drax in South Yorkshire, have introduced flue gas desulphurisation

equipment to reduce emissions of SOx. However, whilst this reduces atmospheric

pollution problems, it creates new pollution problems of a largely terrestrial nature.

There is a need to quarry limestone (calcium carbonate) (see Chapter 4) which is needed

for the cleaning process, and then the waste product, gypsum (calcium sulphate), needs

to be disposed of. This partly explains why relatively clean gas-fired power stations,

TABLE 18.3 Effects of acid deposition

JONATHAN HORNER

394

which were referred to earlier in the section, have been a favoured UK electricity

generation method in recent years. Additionally, low NO

x

emitting burners have been

fitted in many power stations and NO

x

emissions from cars have been reduced by catalytic

converters. A major worry must be that the problems caused by acid deposition are now

being repeated in the industrialising nations of Asia, Eastern Europe and Latin America

where there are lesser controls. Concerns about acid rain may well resurface in the UK

media as the next millennium approaches.

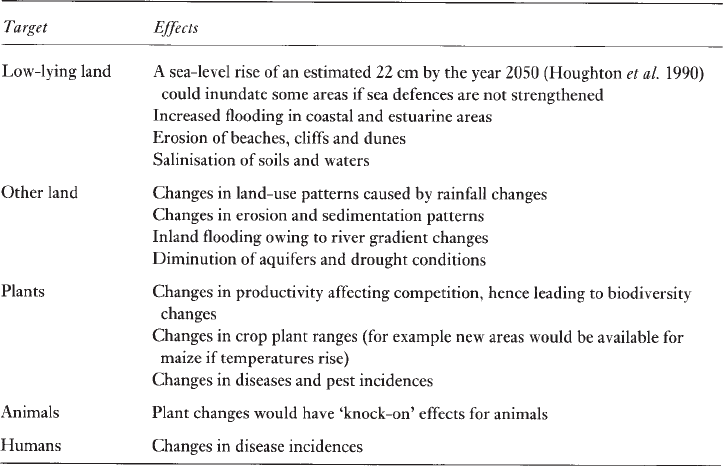

Last to be considered in this section are the truly global air-pollution-related

problems —climate change and stratospheric ozone depletion. It is becoming

increasingly clear that emissions of certain pollutants can now affect processes on a

planetary scale. Increasing concentrations of ‘greenhouse gases’ from human activities

arc expected to cause a significant change in the earth’s climate. This may have

important consequences for the landscape of the United Kingdom (Table 18.4),

considered in Chapter 19, and for water resources, considered in Chapter 2. The main

gases involved are carbon dioxide (CO

2

), methane (CH

4

), nitrous oxide (NO),

chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and ozone (O

3

). These gases absorb outgoing infra-red

radiation which has been reradiated from the earth’s surface. Observed global

temperature increases over recent years are consistent with estimated increases caused

by increased greenhouse gas concentrations. Although a molecule of CO

2

is less potent

than molecules of other greenhouse gases, the quantity of emissions is relatively so

large that CO

2

is the major contributor to global warming. Under its Climate Change

Programme, the UK is committed to reducing CO

2

and CH

4

emissions to 1990 levels

by the year 2000. Total UK emissions of CO

2

fell by 7 per cent, and of CH

4

by 15 per

cent, between 1990 and 1995, largely reflecting the decreasing use of coal in power

TABLE 18.4 Potential effects of global climate change in the UK

POLLUTION

395

stations, and the decrease in deep mining of coal, respectively (Figure 18.4). However,

international action is needed if global atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse

gases are to be reduced.

Stratospheric O

3

absorbs harmful ultraviolet radiation, preventing it from reaching

the earth’s surface. Depletion of this ‘ozone layer’ allows more ultraviolet light to reach

the earth’s surface, causing the effects summarised in Table 18.5. Increases in atmospheric

chlorine and bromine concentrations have been shown to be the major cause of O

3

depletion. These are derived from CFCs, which are used mainly as aerosol propellants,

refrigerator coolants and foam-blowing agents, and from bromofluorocarbons (halons),

which are used in fire extinguishers. Measurements over Lerwick in the Shetland Islands

and Camborne in Cornwall have shown a general trend for decreasing O

3

levels since the

early 1980s (DoE 1996). Although O

3

levels above the UK have not diminished sufficiently

to identify significant effects on human health or crop yields to date, calculations have

indicated that a UK child’s lifetime risk of developing non-melanoma skin cancer under

current depletion rates is 10–15 per cent higher than the risk under an intact O

3

layer

(Diffey 1992). Ecological damage has been identified closer to the Poles where more

serious O

3

depletion has occurred. Concerns in the UK have led the government to set up

an Ultraviolet B (UVB) Measurements and Impacts Review Group and to initiate a £1.5

million research programme to consider UVB’s potential impact on skin cancer (Great

Britain 1996). International action is needed to reverse the trend for O

3

decrease and to

FIGURE 18.4 Total UK emissions of carbon dioxide and methane, for the period 1980–95

Source: DETR (1997).