Gardiner V., Matthews H. The changing geography of the United Kingdom

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

MIKE HULME

416

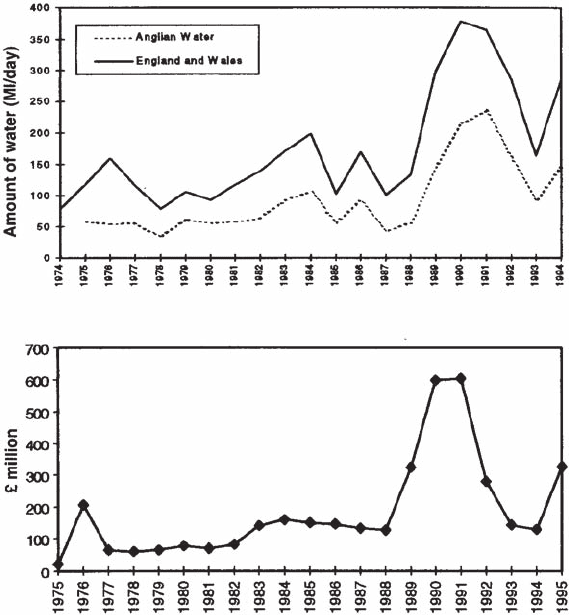

unusually hot and dry seasons or years. Abstraction rates more than trebled during the

drought of 1989–92 and again during 1994–5 as farmers compensated for the lack of

rainfall and high evaporation rates by spray irrigating their crops, particularly in the Anglian

Water region. A similar pattern is evident for subsidence insurance claims. During the

1989–92 drought subsidence claims increased by a factor of six to about £600 million per

year, and the dry weather of 1995 led to at least a trebling of claims. In contrast, the

1975–6 drought saw only a doubling of insurance claims for subsidence. This latter

observation illustrates an important point about the sensitivity of different economic sectors

to climate variability—the relative sensitivities of such sectors to climate variability

themselves change over time. This may either occur as a function of changing economic

or cultural circumstance (there were more home owners in 1991 than in 1976), but also as

a result of specific adaptations to climate extremes (more homes were insured against

subsidence in 1991 than in 1976). This consideration is most important when it comes to

assessing the likely impacts of future climate change on either economic or environmental

systems—past sensitivity is not necessarily a good guide to future sensitivity and a large

array of adaptation strategies may lessen the impact of climate anomalies in the future

(Subak et al. 1999).

We have demonstrated the inherent variability of UK climate on different time-

scales and we have shown how different environmental assets and economic activities

are sensitive to such climate variations. But just how rapidly is UK climate warming

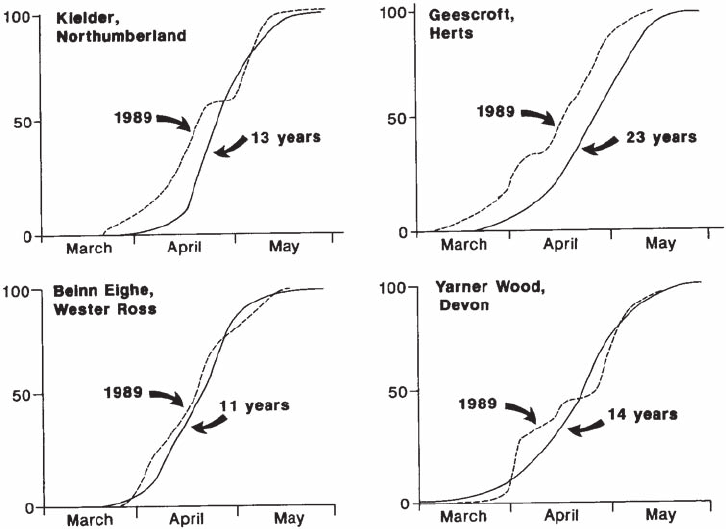

FIGURE 19.5 Total catch of the moth Hebrew character, orthosia gothica (L.) (Lep. Noctuidae) in

light traps at four UK locations in 1989 compared to the mean for all previous years of trapping

Source: Cannell and Pitcairn (1993).

CLIMATE CHANGE

417

and what are the associated changes in non-temperature variables such as

precipitation, gale frequencies and sea-level? The next section presents some

indicators of climate variability over past centuries, while the fifth section (pp.

423–31) presents scenarios of UK climate change for the next century and a summary

of their possible impacts.

Some key indicators of UK climate change and variability

The UK possesses some of the longest instrumental climate time-series in the world,

the longest being the 340-year series of Central England Temperature referred to above.

This presents a unique opportunity to examine climate variability in the UK on long

time-scales based on observational data. It would be advantageous if we could treat

these long time series as describing purely natural climate variability, thus enabling us

FIGURE 19.6 Top panel: water abstraction for agricultural use (spray irrigation in ml/day) for 1975–

94 for England and Wales and for the Anglian Water region; bottom panel: subsidence-related domestic

insurance claims at 1995 prices for 1975–95

Source: Subak et al. (1999).

Note: Many claims pertaining to the 1994–5 climate anomaly would appear in 1996 or 1997 data

which are not shown.

MIKE HULME

418

better to identify what level of human-induced climate change may truly be significant.

This would not be a correct interpretation, however, since—at least during the most

recent century—human forcing of the climate system has been occurring through

increasing atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases and sulphate aerosols. This

has allowed scientists to detect a ‘discernible human influence on the global climate

system’ (IPCC 1996:4). What we observe therefore, and this is as true for the UK as it

is for the world as a whole, is a mixture of natural climate variability and human-

induced climate change, with the contribution of the latter increasing over time. It is

nevertheless very instructive, before we progress to examine future climate change

scenarios for the UK, to appreciate the level of climate variability that the UK has been

subject to over recent generations.

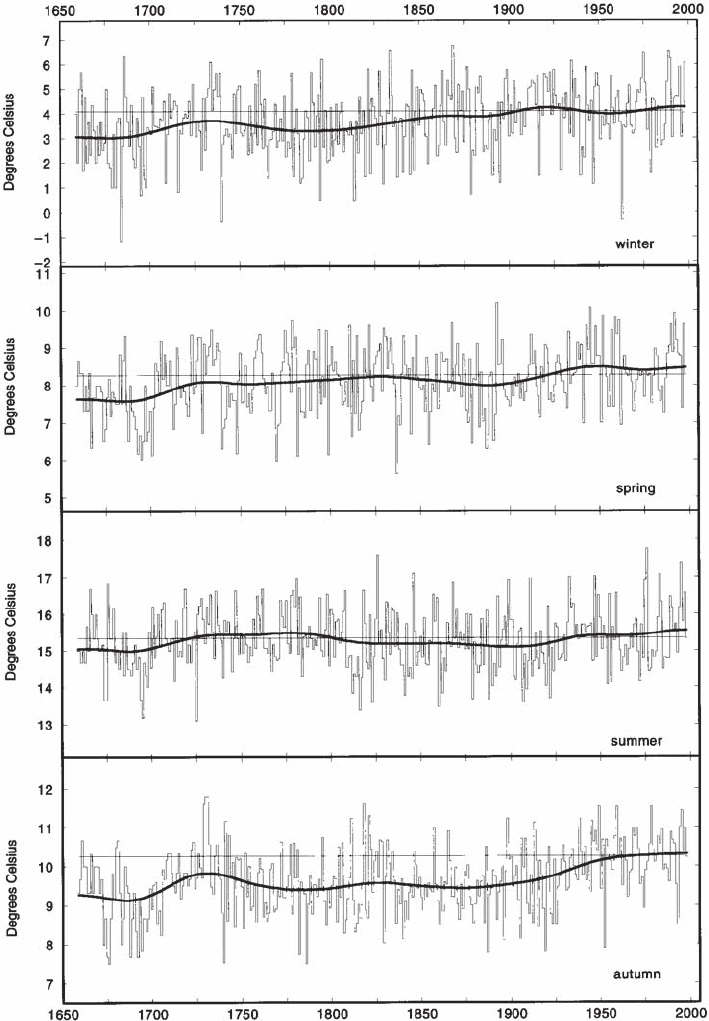

Temperature indicators

The Central England Temperature series has already been referred to and an annual

version of the series plotted in Figure 19.3. Here, we show the four seasonal components

of this series smoothed with a 100-year filter to emphasise the century time-scale trends

(Figure 19.7). The greater warming in winter compared to summer is clear, although

most of this winter warming occurred before the present century commenced. Autumns

over recent decades have averaged nearly 1°C above the full period mean, while the

cluster of warm springs at the end of the series has meant that this season also has never

been as mild as it has over the last decade. The unusual warmth of the decade 1989–98

in the UK is supported by the sequence of very warm months and seasons shown in

Table 19.2.

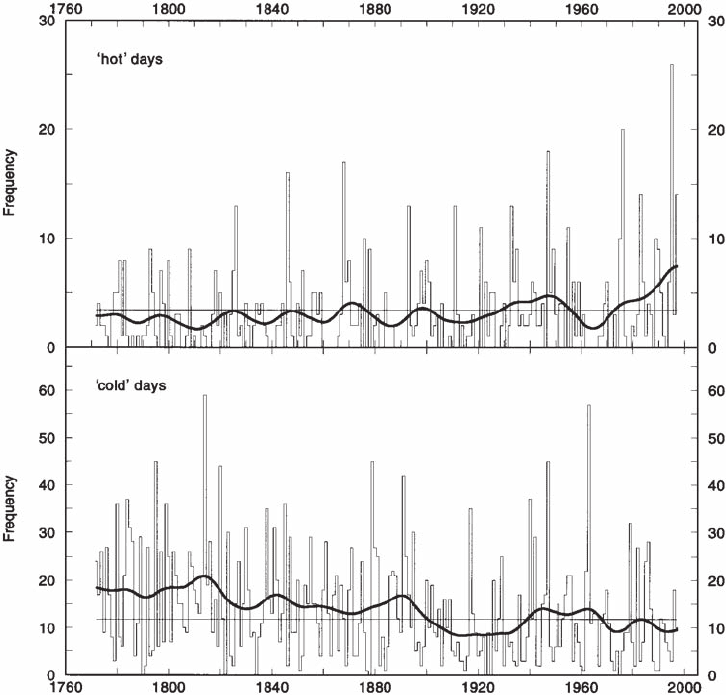

The Central England Temperature series can also be used to examine changes

in daily temperature extremes, although in this case data are only available since

1772. Figure 19.8 shows the annual frequencies of ‘hot’ and ‘cold’ days in Central

England over these two centuries. There has been a marked reduction in the frequency

of cold days since the eighteenth century, these frequencies falling from between

fifteen and twenty per year to around ten per year over recent decades. There has not

been a commensurate rise in the frequency of hot days, although as with annual

temperature the last decade has seen the highest frequency of such days. For example,

1995 recorded twenty-six hot days compared to a long-term average of less than four,

and the decade 1988–97 averaged 7.4 hot days per year, nearly double the 1961–90

average.

Other climatic indicators

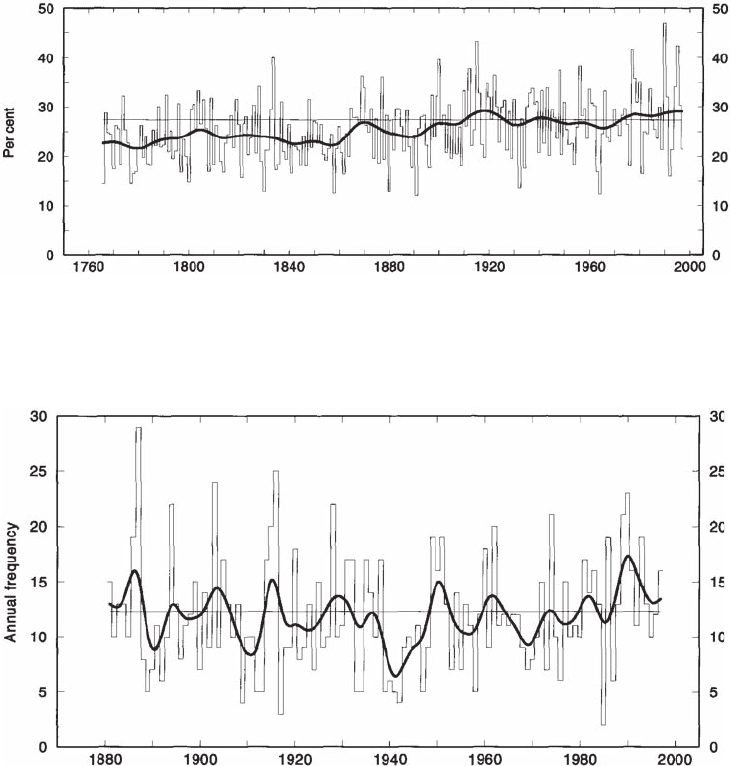

The annual precipitation series for England and Wales and for Scotland are shown

in Figure 19.3 and display little long-term trend. Here, we examine the seasonal

distribution of precipitation with Figure 19.9 showing the proportion of annual

England and Wales precipitation falling in winter (December-February). This index

is a simple measure of the continentality of UK climate—the larger proportion of

precipitation falling in winter the more continental the climate—and this seasonal

distribution of precipitation has important implications for how water resources are

managed. The proportion of precipitation over England and Wales falling in winter

CLIMATE CHANGE

419

FIGURE 19.7 Seasonal Central England Temperatures for the period 1659 to 1997. Horizontal lines

show 1961–90 means. Smoothed curves emphasise century time-scale variability

MIKE HULME

420

has increased over time, rising from about 23 per cent in the nineteenth century to

a 1961–90 average of about 27 per cent. Two of the three years with the highest

index values this century have occurred in the last decade—1990 and 1995 —

although there have also been recent years with quite low proportions of winter

precipitation—1992 and 1997. This shift in the seasonal distribution is a result both

of increased winter precipitation and decreased summer precipitation (not shown)

and is repeated in the Scotland series.

We also show (Figure 19.10) an index of gale activity over the UK, updated

following the analysis of Hulme and Jones (1991). This series is shorter than those for

temperature and precipitation and as with annual precipitation it shows no long-term

trend. Gale activity is highly variable from year to year, however, with a minimum of

two gales in 1985 and a maximum of twenty-nine gales in 1887. The middle decades of

this century were rather less prone to severe gales than the early and later decades,

whilst the most recent decade—1988 to 1997—has recorded the highest frequency of

severe gales since the series began, 15.4 per year compared to an average of 12.3 (see

also Chapter 17).

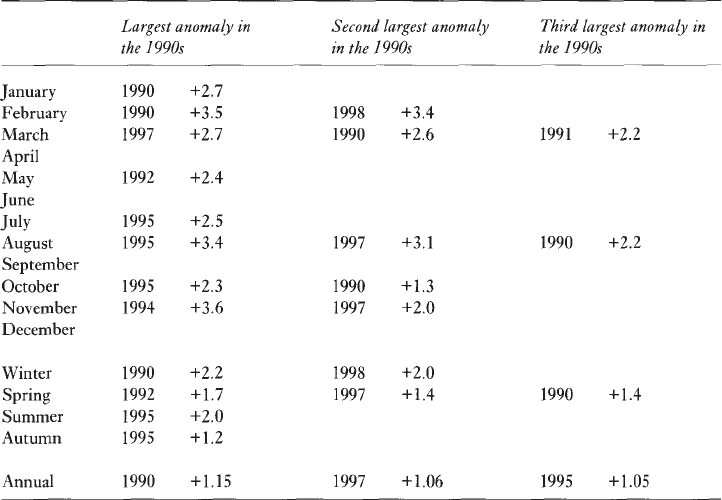

TABLE 19.2 Exceptionally warm months, seasons and years during the 1990s as indicated by the

Central England Temperature series

Note: All the anomalies shown fall in the ten warmest respective months, seasons or years in the

complete 340-year CET series. By chance, and assuming the monthly data are uncorrelated, one would

expect only four months, seasons or years to appear in this table. In fact, twenty-five exceptionally

warm anomalies have occurred during the 1990s. Over this period, only one month—June 1991—has

been exceptionally cold (using the inverse definition). Anomalies are shown in °C with respect to the

1961–90 mean. Data complete to July 1998.

CLIMATE CHANGE

421

There are many factors in the global climate system that have contributed to

these observed changes, but one of the more important for the UK has been the

behaviour of the North Atlantic Oscillation (or NAO). The NAO is a major disturbance

of the atmospheric circulation and climate of the North Atlantic-European region,

linked to a waxing and waning of the dominant middle-latitude westerly wind flow.

The NAO Index we show here is based on the monthly mean sea-level pressure

difference between various stations to the south (Azores and/or Iberian peninsula)

and north (Iceland) of the middle-latitude westerly flow (Jones et al. 1997). It is

therefore a measure of the strength of these zonal winds across the Atlantic. When

the NAO Index is positive, the westerly flow across the North Atlantic and Western

Europe is enhanced. During the winter half-year, the strengthened westerly winds

bring warmer, maritime air over north-west Europe causing a rise in temperature and,

FIGURE 19.8 Frequency of ‘hot’ (Tmean >20°C) and ‘cold’ (Tmean <0°C) days extracted from the

Central England Temperature record for the period 1772 to 1997. Horizontal lines are 1961–90 means

(3.4 and 11.8 days per year respectively) and smooth curves emphasise thirty-year time-scale variability

MIKE HULME

422

usually, precipitation. When the Index is low or negative, the opposite occurs with

temperatures falling over north-west Europe and rising over the north-west Atlantic.

The net result is a ‘see-saw’ or oscillation in temperatures across the North Atlantic-

European sector, as well as changes in other climate variables such as precipitation

and sea-ice extent.

The NAO exerts a strong influence on year-to-year climate variability in the UK. For

example, the correlation between NAO and winter temperature in the UK is about 0.67

(Jones and Hulme 1997). The winter (November to March) NAO Index is shown in Figure

19.11. The period from about 1970 recorded rising Index values, with the highest value

being recorded in 1994/5. The change in NAO condition between the winters of 1994/5 and

FIGURE 19.10 Annual frequency of ‘severe gales’ affecting the UK for the period 1881 to

1997. The horizontal line shows the 1961–90 mean frequency (12.3 per year) and the smooth

curve emphasises decadal time-scale variability

FIGURE 19.9 Percentage of precipitation over England and Wales falling in winter for the period

1766–1997. The horizontal line is the 1961–90 mean (27.4 per cent) and the smooth curve

emphasises thirty-year time-scale variability

CLIMATE CHANGE

423

1995/6 was quite remarkable—from the highest twentieth-century value to the lowest

twentieth-century value in successive years. The very low Index value in winter 1995/

6 was associated with a cold winter in the UK. The 1996/7 Index value was close to the

long-term average and the UK winter was correspondingly milder. The NAO displays

variations on a number of different time-scales, most of which may be unrelated to

global warming. However, given its importance in determining winter weather over the

UK, trends in UK climate cannot fully be understood without reference to the NAO

(Osborn et al. 1999).

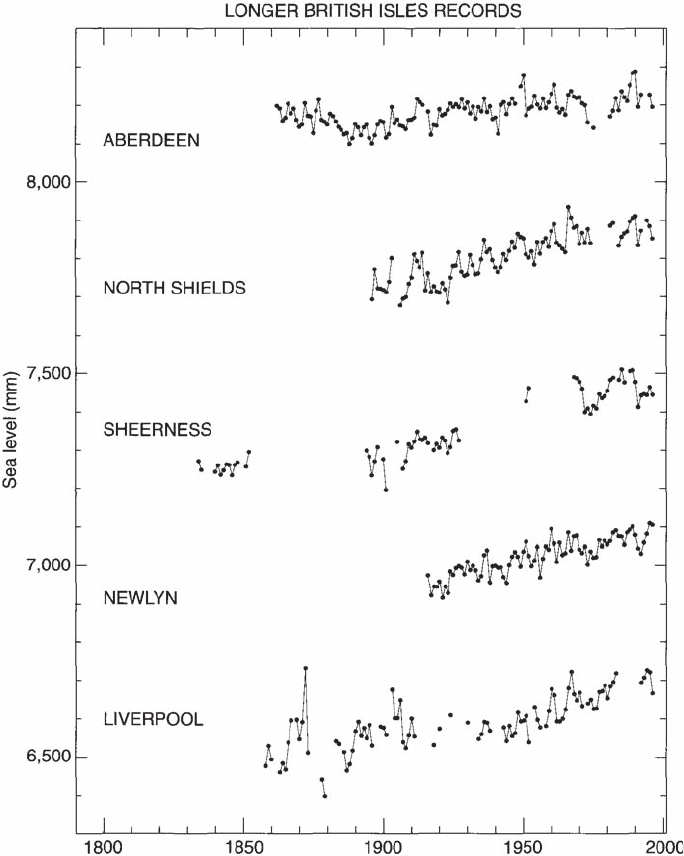

A final indicator of UK climate variability shown in this section is that of sea-

level rise. Climate warming is anticipated to lead to a rise in global-mean sea-level,

primarily because of thermal expansion of ocean water and land glacier melt. Figure

19.12 shows long-term series of tide-gauge data for five locations around the UK

coastline. All of these series indicate a rise in unadjusted sea-level, ranging from 0.7

mm/yr at Aberdeen to 2.2 mm/yr at Sheerness (Woodworth et al. 1999). These raw

estimates of sea-level change need adjusting, however, to allow for natural rates of

coastline emergence and submergence resulting from long-term geological

readjustments to the last glaciation. The adjusted net rates of rise resulting from

changes in ocean volume range from 0.3 mm/yr at Newlyn to 1.8 mm/yr at North

Shields, evidence of an expanding ocean at least around the shores of the UK (see

Chapter 17).

Future changes in UK climate

Having established from proxy indicators and from the observed record that UK climate

varies naturally on a variety of time-scales, we now wish to consider what the future may

hold. To do so we have to consider the mechanisms which control UK climate, which

requires an understanding of two sets of factors. These are, first, the array of physical

processes and interactions within the climate system that shape the variations in UK climate

on these different time-scales and, second, the range of forcings that are external to the

FIGURE 19.11 NAO Index for the extended-winter period (November to March) from 1825/6 to

1997/8 (dated by January). The Index is the normalised sea-level pressure difference between Gibraltar

and south-west Iceland. Units are dimensionless. The smooth curve emphasises variations on time-

scales of thirty years

MIKE HULME

424

climate system but which have a profound effect on the way it functions. To achieve this

understanding in the most comprehensive way possible we need to rely upon climate

models. Climate models enable us, on a range of spatial and temporal scales, to investigate

the variability of climate that results from internal feedbacks within the climate system.

We can also use these models to examine the relative consequences for climate of imposing

FIGURE 19.12 Relative changes in sea-level over the last 100–150 years as recorded by tide gauges at

five UK locations. Last year of data is 1995 or 1996 and units are millimetres. Data are unadjusted for

crustal movements

Source: Woodworth et al. (1999).

CLIMATE CHANGE

425

different magnitudes of external forcing on the system, whether this forcing be changes

in solar activity, aerosols resulting from volcanic eruptions, or changes in the concentrations

of greenhouse gases in the global atmosphere. In this section, we use results from global

climate model experiments to present a range of future climate scenarios for the UK. In

this approach we follow the science reported by the IPCC in their Second Assessment

Report (IPCC 1996) and also used in the UK national climate change scenarios prepared

for the UKCIP in 1998 (Hulme and Jenkins 1998).

Future climate without climate change

We consider first the possible UK climate of the period around the 2050s decade in

the absence of any external forcing. That is, we assume that there are no further

increases in greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere and that there is no

significant change in solar output nor any major volcanic eruptions between now and

then—these are, of course, artificial assumptions, but it helps us to identify the range

of possible climates that we would need to adapt to in the absence of climate change.

For this exercise we rely upon the results of a 1,400-year simulation of unforced

global climate by the Hadley Centre global climate model, HadCM2. By using this

model simulation as a description of natural climate variability we can define the

probability distribution of thirty-year mean climate states for the UK centred on the

decade of the 2050s (Figure 19.13). While all of these seasonal distributions of mean

temperature and precipitation are centred on zero (that is, there is an equally likely

chance of mean temperature or precipitation increasing or decreasing by this period),

it is the tails of the distributions that are most important for policy. Thus, even in the

absence of any climate change, over south-east England there is a finite chance of,

for example, (a) annual precipitation for the period 2040–70 averaging 8 per cent

higher or lower than the 1961–90 average, or (b) mean annual temperature for this

thirty-year period being 0.5°C warmer or colder than at present. Similarly, there is a

50 per cent chance that the annual climate of this part of the UK will be more than 2

per cent wetter or drier than now and a 50 per cent chance of it being more than

0.15°C warmer or colder. Furthermore, Figure 19.13 shows that the possible ranges

for seasonal change—in particular summer precipitation—are considerably larger than

these annual values, although over northern UK the ranges are slightly smaller than

over southern UK.

We start our description of possible future UK climate with this analysis of

unforced natural variability in climate on thirty-year time-scales because it is often

assumed that the only thing we have to plan for is human-induced climate change

(popularly referred to as ‘global warming’). This is not the case, as we have shown.

To take a more specific example, consider what level of summer rainfall variability

the water industry has to be able to manage successfully. Without climate change

affecting the UK and if, hypothetically, we were able to experience a large number

of climate states for the 2050s, then on average summer rainfall during 2040–69

will be similar to what it has been during 1961–90. In reality, however, we only

experience the 2050s once and Figure 19.13 shows that for south-east England

there is a 10 per cent risk that over this period summer rainfall will be averaging

7 per cent less than the 1961–90 mean and a 10 per cent chance that it will be