Gardiner V., Matthews H. The changing geography of the United Kingdom

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

406

Chapter 19

Climate change

Mike Hulme

Introduction

Climate: the condition of a region or country in relation to prevailing atmospheric phenomena

such as temperature, humidity, etc., especially as these affect animal or vegetable life.

(OED 1973)

The climate of a place is one of its most important physical attributes. The unique sequence

of weather events experienced at a place over a long period of time determines to a

considerable extent the nature of the surface landforms, the mix of vegetation and the

potential of the place to act as a habitat for different species, including humans. The

climate of a country may often be one of the fundamental unifying characteristics of its

national identity. The shared experience by a community of the march of the seasons, of

weather extremes or of the climatic resources of a region, creates a common set of climatic

perceptions and instincts that are almost a language in themselves. These two roles of

climate have been recognised throughout human history, and the cultural response of

humans to different climates—in both space and time—has left imprints on both the

natural and social environment that are among the most distinctive. These imprints range

from physical artefacts such as irrigation infrastructures or flood defences, to intellectual

constructs such as climatic determinism (Huntington 1915) and the defining of certain

racial characteristics of different nations. Although this close relationship between climate

and its induced human response has long been recognised, awareness of the inverse

relationship—the response of climate to different human activities—is of more recent

origin. While the human modification of microclimates—whether inadvertent through

expanding cities or deliberate through planting trees—has a substantial history, the

understanding that human actions can modify larger-scale synoptic circulation, or even

global climate, has only penetrated widely through the intellectual world during the latter

decades of the twentieth century.

CLIMATE CHANGE

407

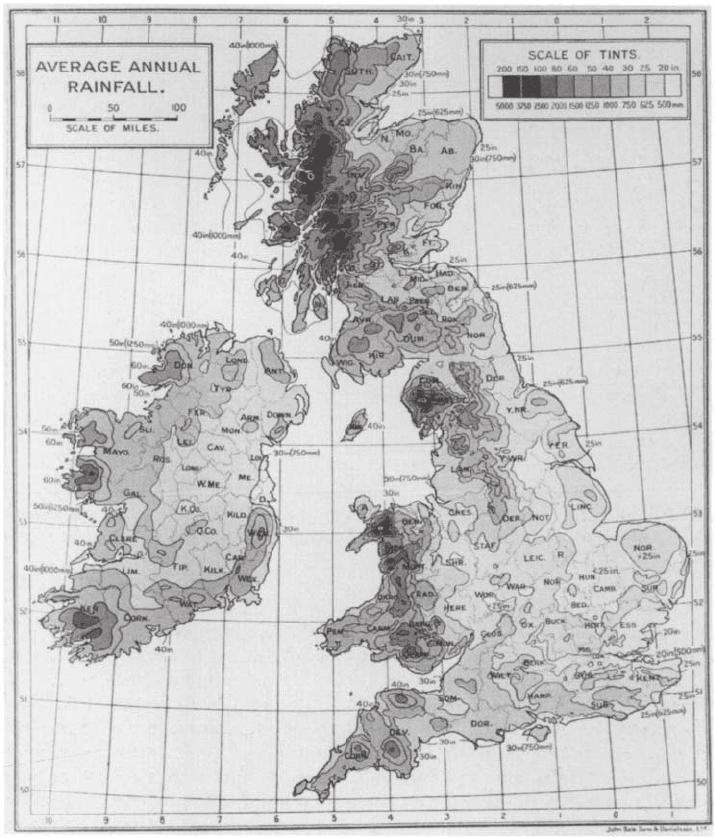

This changed perception of climate, and of its potential to be changed, is as true for

the UK as it is for other nations. Thus for much of the present century, climate ‘normals’ for

the UK were defined as thirty or thirty-five year averages (e.g. Royal Meteorological Society

1926; Figure 19.1) and these were commonly regarded as providing definitive descriptions

of that most characteristic of British ‘institutions’, the climate. Similarly, the standard climate

textbook of the 1970s, Tony Chandler and Stan Gregory’s The Climate of the British Isles

published in 1976, implicitly subscribed to this static view of climate through its title, even

FIGURE 19.1 Average [sic] annual rainfall for the British Isles, based on 1880–1915 data, measured

in inches

Source: Royal Meteorological Society (1926).

MIKE HULME

408

though the book devoted one concluding but rather brief chapter to climate change. Or

taking the example of the present book, The Changing Geography of the UK, neither the

first nor second editions, published respectively in 1983 and 1991, contained a chapter on

climate change or even on climate, despite the book explicitly dealing with changes in the

geography of the UK.

A number of intellectual developments and climatic events have led to this increasing

awareness of the importance of climate variability, some specific to the UK and some related

to the worldwide stage. The pioneering scholarly work of the late Hubert Lamb ranks highly

among the former. For over half a century, Professor Lamb endeavoured to bring to the

attention of a wider public his belief in the reality of climate change on human time-scales,

an endeavour that culminated in the publication of Volumes I and II of his mammoth work

Climate: Present, Past and Future in, respectively, 1972 and 1977 (Lamb 1972, 1977). He

also founded, in 1972, the Climatic Research Unit at the University of East Anglia, a research

centre that has developed into one of the world’s leading centres for research into climate

change. Among the latter set of reasons—notable climate events—the great drought of

1975–6 was a landmark climate anomaly in the UK, a drought of such significance that it

prompted the publication of an atlas dedicated to the character and consequences of the

drought (Doornkamp et al. 1980).

In the political sphere, the speech to the Royal Society delivered by the Prime

Minister, Mrs Thatcher, in September 1988 marked a sea-change in the response of the

UK government to the prospect of significant climate change. The core funding of the

Hadley Centre for Climate Prediction and Research, opened in May 1990, was guaranteed

and this centre now contains perhaps the world’s leading climate modelling group. And

at a global level, the series of increasingly warm years during the 1980s and 1990s (1981,

1983, 1988, 1990, 1995, 1997 and 1998 all set new annual records for global-average

surface air temperature) provided the empirical impetus to the realisation that global climate

was changing. This sequence of record warm years paralleled developments in the

institutional framework of global climate science. In 1988, the World Meteorological

Organisation (WMO) and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) established

the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), and four years later at the Earth

Summit in Rio de Janeiro the Framework Convention on Climate Change (FCCC) was

signed by over 150 nations under the auspices of the United Nations. The IPCC provided

an emerging scientific consensus concerning the nature and causes of global climate

change, while under the instruments of the FCCC a Protocol for limiting the growth of

climate-warming greenhouse gases was first agreed at the Kyoto Climate Summit in

December 1997 (Bolin, 1998).

As the century ends, therefore, not only is the physical reality of climate in the UK

different from what it was just fifty or a hundred years ago—as this chapter will elucidate—

but the intellectual construct of climate is also very different. Climate, within the UK and

also globally, is now seen as continually changing. Past climate statistics, defined over

thirty or so years, are no longer an adequate guide to the future. Private industries (such as

those concerned with water and insurance) and public bodies (such as the Environment

Agency and the Countryside Commission) commission studies and reports that quantify

the likely range of climate change to be realised next century. These estimates are

subsequently incorporated into their long-term strategic planning activities (see Arnell et

al. 1997, as an example for the water industry). An important boundary condition of the

CLIMATE CHANGE

409

geography of the UK is changing and can no longer be viewed as fixed. The components of

the geography of the UK that are most sensitive to climate are therefore also subject to

climate-induced change.

Before looking at some of these sectoral sensitivities (pp. 413–17) and summarising

some of the key indicators of UK climate change (pp. 417–23), the chapter starts with

a very brief survey of the historical change in UK climate over recent millennia and

centuries (pp. 409–13). The fifth section (pp. 423–31) then looks at what the UK climate

of the next century may be like and evaluates the significance of this prospect for the

national UK economy and environment. The national and international climate policy

initiatives relating to these changes are discussed on pp. 431–33, while the concluding

section provides some reflections on future climate-society interaction in the UK.

Throughout this chapter the terms climate variability and climate change are used with

specific meanings. Climate variability is used to describe fluctuations in climate on all

time-scales, but occurring due only to natural internal variability in the climate system.

The term climate change is reserved for climate variability induced by some external

forcing agent, whether natural (e.g. volcanic eruptions) or human (e.g. greenhouse gases)

in origin.

A brief history of recent UK climate

The annual mean temperature of the UK over the most recent ten-year period (1989–98)

has averaged about 8.9°C, very nearly 1°C warmer than the average UK temperature of the

last 300 years. This has without doubt been the warmest decade in the period for which we

have instrumental measurements, a decade in which the warmest single year—1990, 1.45°C

warmer than the 300-year average—also occurred. How this warmth compares with earlier

decades or years in the UK, for example during the late medieval period of the thirteenth or

fourteenth centuries or even earlier during the early Holocene about 8,000 years ago, is

much harder to establish.

Climate variability in the Holocene

That the climate of the UK has varied substantially over these millennia is of course well

established. One of the more enlightening methods for reconstructing temperatures in the

UK over this period of time has been to examine the assemblages of particular beetle

species, identified as dated remains in a number of late glacial and Holocene sites in the

UK (Atkinson et al. 1987). Using the ‘mutual climatic range’ method the annual mean

temperature of these sites has been deduced for more than fifty discrete time points within

the period of transition from glacial to interglacial climates, a period from roughly 15,000

to 8,000 years BP. A further eight climatic ‘snapshots’ have also been reconstructed during

the few thousand years before and after this glacial-interglacial transition. This

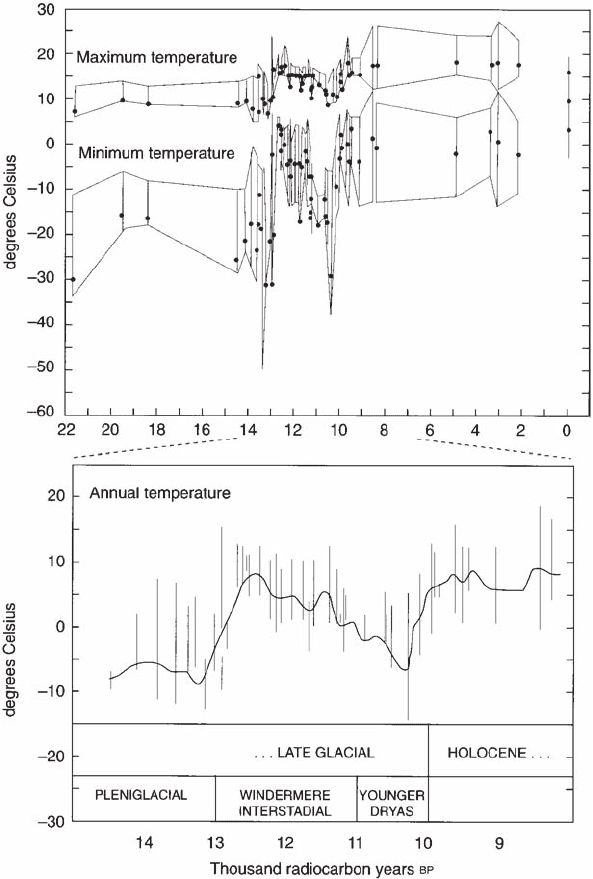

reconstruction (Figure 19.2) provides quantitative evidence for major changes in UK

climate as the Devensian ice-sheet retreated and the warmer climate of the Holocene

became established. From this evidence, UK mean annual temperature was between -9°

and -6°C during the last centuries of the Devensian period, rising to a temperature more

typical of recent centuries (7° to 9°C) by the early Holocene at about 10,000 years BP.

Since then, temperatures in the UK on at least century time-scales have probably not varied

MIKE HULME

410

FIGURE 19.2 Temperature changes in the British Isles during the late glacial and Holocene periods

estimated on the basis of beetle remains. Top panel: maximum and minimum temperature for 22,000

years BP to present; bottom panel: annual temperature for 15,000 to 8,000 years BP. The dots indicate

the most probable values within the temperature ranges. The values plotted at 0 (i.e., ‘today’) in the top

panel are the mean (dot) and maximum range (bar) of the Central England Temperature series over the

period 1659–1995

Source: Briffa and Atkinson (1997).

CLIMATE CHANGE

411

by more than about ±1°C, although we cannot say quantitatively what the spectrum of

annual temperature variability has been on shorter, decadal or annual, time-scales. It is for

this reason that we cannot be certain just how unprecedented the warmth of the 1989–98

decade in the UK has been.

It is even harder to reconstruct quantitatively the precipitation history of the UK

over the Holocene. The changing distribution and abundance of certain vegetation species

perhaps offer themselves as the most useful proxies for reconstructing moisture changes,

although separating out the different effects of temperature and moisture change on species

is not always easy. For example, a tree-ring-width chronology based on Irish bog oaks

resolves the annual growth of this tree species in Ireland over the period from 7,500 to

2,000 BP. This index is a function of July/August growing conditions such that high

growth is associated with warm/dry conditions and low growth with cool/wet conditions

(Briffa and Atkinson 1997). Notably warm and dry conditions appear to have been more

frequent between 7,000 and 6,400 and 5,900 and 5,450 BP, whereas longer cool/wet

conditions are suggested between 6,400 and 5,900 BP, 4,200 and 3,900 BP and between

3,150 and 2,750 BP. These reconstruction efforts give support to the notion of meaningful

climate variability having occurred in the UK on these multi-century time-scales, but

without being able to quantify such variability fully or to resolve its interannual or

interdecadal frequency spectrum.

Climate variability in the last millennium

Climate reconstruction using documentary sources from more recent history suffers

from similar limitations. Various medieval annals, chronicles and account rolls of English

manors reveal useful information about weather extremes and seasonal climate anomalies

in the preinstrumental period of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries (Ogilvie and

Farmer 1997). They are limited, however, in not enabling us to state with confidence

how many warm years and decades there were during this so-called medieval warm

epoch nor exactly how warm such years or decades were relative to today’s conditions.

For this precise quantitative information on early UK climate we have to rely on the

instrumental record of climate. The longest homogeneous instrumental series in the

world of monthly resolved mean temperature and precipitation originate from the UK.

These commence in 1659 for mean temperature—the Central England Temperature

(CET) record of the late Gordon Manley (1974) —and in 1757 and 1766 for

precipitation—the Scotland precipitation series of Smith (1995) and the England and

Wales Precipitation (EWP) series compiled by Tom Wigley and Phil Jones following

earlier work by Nicholas and Glasspole (1931).

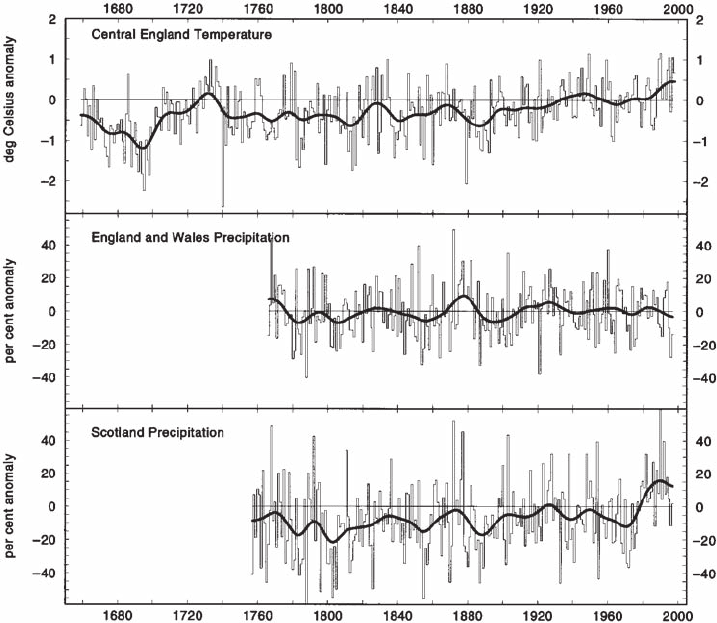

These three series are shown in Figure 19.3 and provide us with the longest quantitative

context for evaluating the climate variability observed in the UK in recent decades. The

average temperature of central England as defined by the CET is about 1.2°C warmer than

for the UK as a whole (i.e., 10.1°C during 1989–98, compared to 8.9°C for the UK), but the

interannual and interdecadal variations captured by the CET are representative of nearly the

whole UK domain. The annual warming of UK climate over the period from 1659 has been

about 0.7°C, with a stonger warming in winter (1.1°C) compared to summer (0.2°C; see

Figure 19.7).

MIKE HULME

412

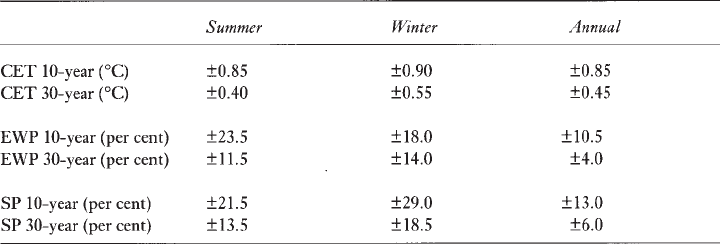

Analysis of the detrended CET series shows that the decadal variability of

annualmean temperature is about ±0.85°C and the thirty-year variability is about ±0.45°C

(Table 19.1). We can calculate similar levels of ‘natural’ variability for precipitation,

although in this case only the Scotland series displays any trend over time. The last

twenty years in Scotland have been substantially (+20 per cent) wetter than any equivalent

period in the last 240 years, with the wettest year on record occurring in 1990.

Precipitation variability on a thirty-year time-scale is greater than ±10 per cent for both

winter and summer, rising to over ±20 per cent for decadal-scale variability. These

relatively large levels of ‘natural’ climate variability are of fundamental importance

when considering the sensitivity of UK resources and institutions to climate change

(see pp. 429–31).

This brief overview has provided evidence for the non-stationary character of UK

climate over both shorter and longer time-scales. This climate variability has over the

ages of millennia greatly shaped the landscape of our country and over the ages of

centuries provided a constraint within which our economic, social and cultural heritage

FIGURE 19.3 Annual anomalies for Central England Temperature (top), England and Wales

Precipitation (middle) and Scotland Precipitation (bottom) with respect to 1961–90 mean (horizontal

lines). The smooth curves emphasise variations on thirty-year time-scales. Last year is 1997

CLIMATE CHANGE

413

has developed In the next section we provide some examples of how different economic

and environmental assets within the UK are sensitive to different magnitudes of climate

change and variability.

The sensitivity of the UK to climate change and variability

Climatic determinism

It is a truism to state that environmental systems and human activities are influenced by

climate. One only needs to think of the uneven abundance of surface water availability

between the north-west and south-east of the UK, the siting of vineyards in the counties

of eastern and southern England, or the summer timing of our outdoor national sporting

events to recognise the role, sometimes almost subliminal, of climate in our national

life. The study of climate-environment-society interactions has a long history and has,

at times, led to rather exaggerated claims about the extent to which different climates

can affect—or determine—human culture. Determinism is a reductionist philosophy

that sees events and behaviour as controlled by a very limited set of physical factors.

Ellsworth Huntington, the Yale geographer, has perhaps been the best-known proponent

of such a role for climate. He argued in 1915 that, ‘The climate of many countries

seems to be one of the great reasons why idleness, dishonesty, immorality, stupidity,

and weakness of will prevail’ (Huntington 1915: 411). Although not always as strident

or doctrinaire as Huntington, the importance of the climatic influence on our lives has

been stressed by numerous thinkers, starting with the ancient Greeks and their supposedly

uninhabitable, torrid and frigid ‘climata’. The influence of climate has also been

interpreted psychologically. In the middle of this century, for example, Manley (1952:22)

stated that, ‘Appreciation of the British climate depends largely on temperament. That

it has not been conducive to idleness has been reflected in the characteristics of the

people’ and, more recently, Beck (1993:63) argued that ‘the historical record is highly

suggestive…that a mild climate in mid-latitudes helps to foster a tolerant society or

that an extreme climate may predispose people towards intolerance’.

TABLE 19.1 Levels of ‘natural’ climate variability in detrended seasonal and annual series for Central

England Temperature (CET), England and Wales Precipitation (EWP) and Scotland Precipitation (SP)

on ten-year and thirty-year time-scales

MIKE HULME

414

Without falling into the dangers of climatic determinism, it is important that we discover

just how sensitive different environmental systems and human activities are to climate and

hence to climate change and variability (Hulme and Barrow 1997). Or, put differently, to

what climate regime are these functions best adapted and, if they are well adapted to the

current regime, how vulnerable are they to differing magnitudes of climate change and

variability? To take the three examples mentioned above—what would happen to UK water

resources were there to be a shift in the patterns of precipitation across the UK? How would

the British wine industry respond to a further 1°C warming in UK summer climate? And

how would our summer sporting culture change should summers become drier and warmer?

These are questions not of abstract intellectual curiousity but, given that we have demonstrated

that UK climate varies on different time-scales quite naturally, are of major importance for

national welfare. The questions become even more important when we consider the prospect

of accelerated climate change, over and above natural climate variability, occurring as a

consequence of human-induced changes in atmospheric composition. It is with these thoughts

in mind that the UK government established in 1997 the UK Climate Impacts Programme

(UKCIP) with a programme office at the University of Oxford. In the next part of this

section we give some examples of climate sensitivity within the UK.

Sensitivity to climate variability and climatic extremes

The changing temperature of central England over past centuries has already been illustrated

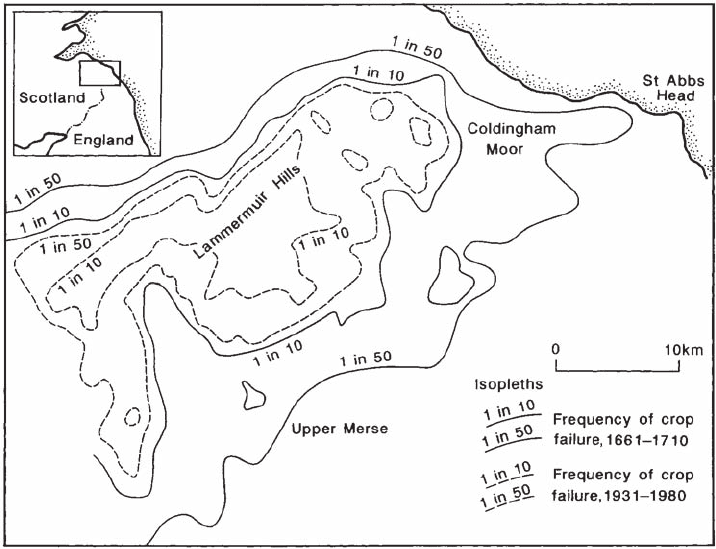

(Figure 19.3). In a study published in 1985, Martin Parry and Tim Carter showed how the

risk of oat crop failure in the Lammermuir Hills of southern Scotland is sensitive to different

climatic regimes within this period of record (Figure 19.4). The 1-in-10 and 1-in-50 risk of

failure contours contract substantially during the mild period of 1931–80 compared to the

colder conditions prevalent during the period 1661–1710. This later period was on average

about 0.8°C warmer than the period in the seventeenth century. Such changes in agricultural

risk have major implications for farm management practices and consequently for human

settlement and the nature of the landscape.

Other relevant work has examined the consequences for the UK environment

(Doornkamp et al. 1980; Cannell and Pitcairn 1993) and UK economy (Subak et al. 1999)

of recent seasonal or annual climate anomalies. Thus Cannell and Pitcairn (1993) concluded

that one of the main environmental impacts of the warm UK climate of 1989 and 1990 (a

two-year mean temperature anomaly about 1.4°C above the 300-year average) was an increase

in the abundance, activity and geographic spread of many insects. Some of these insects

were pests—aphids or wasps—while others such as butterflies, moths and crickets may be

said to have enhanced the natural environment. Increased honey production by bees during

these two years was certainly welcomed by producers. Figure 19.5 shows the sensitivity of

the activity and abundance of one moth species to the 1989 climate anomaly, in effect

bringing forward its life cycle by between one and three weeks. Other environmental effects

of this warm two-year period included the increase in nuisance blooms of blue-green algae

on many lakes and reservoirs, lasting damage to mature broadleaved trees in the south-east

of England, and the enhancement of fruiting and seeding of many warmth-loving herbaceous

species.

A more comprehensive assessment of UK economic sensitivity to a climate

anomaly was completed by Subak et al. (1999) following the record-breaking twelve-

CLIMATE CHANGE

415

month period from November 1994 to October 1995. This period experienced a mean

temperature anomaly of 1.9°C above the 300-year average, the warmest twelve-month

period in the entire Central England Temperature series (Hulme 1997). The study was

distinguished by its breadth of coverage, which included consideration of impacts on

secondary industries as well as on tertiary and primary production sectors. These

activities and sectors were agriculture, water supply, forestry, health, human behaviour,

fires, energy, retailing and manufacturing, construction and buildings, transportation

and tourism. Both negative and positive impacts of the warm weather were incurred

within most sectors. Net positive impacts (to the general public) were found convincingly

for energy and health, and clear negative impacts for agriculture, water supply and

buildings insurance. It appeared that for most areas of human activity in the UK the

greatest impacts were sustained from anomalous warm winter weather rather than from

unusually hot summer weather.

Examples of water abstraction and domestic insurance

Two specific examples of sensitivity to such climate variability are shown in Figure 19.6 —

water abstraction licences and subsidence-related domestic insurance claims. Water

abstraction for agricultural applications in England and Wales increases dramatically during

FIGURE 19.4 Locational shift of contours for risk of oat crop failure (1-in-10 years and 1-in-50 years)

between cool (1661–1710) and warm (1931–80) periods in the Lammermuir Hills, south-east Scotland

Source: Parry and Carter (1985).