Gardiner V., Matthews H. The changing geography of the United Kingdom

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

CHRIS PARK

446

land cover and landscape are ‘to protect the countryside for its landscape and habitats of

environmental value while maintaining the efficient supply of good quality food and

other products’.

Data on these two families of indicators, contained in the Indicators of Sustainable

Development report, have been used in constructing the following sections of this chapter.

Preservation and conservation

To treat landscape preservation and wildlife conservation as separate themes would be to

deny their interrelatedness and co-dependency. It would also run counter to both the spirit

and purpose of recent government initiatives—including the institutional changes described

earlier—designed to preserve the environmental estate of the United Kingdom. A more

sensible and realistic approach is to identify some core themes that are relevant to both

landscape preservation and wildlife conservation, whilst recognising that some themes are

more appropriate to one than the other.

Competition and conflict

A critical tension underlies and challenges all debates about how to manage the natural

resources of the United Kingdom in a sustainable manner. It stems from the obvious fact

that the land resources are required to meet a range of different objectives at the same time,

not all of which are compatible. Hence ‘a key sustainable development issue is to balance

the protection of the countryside’s landscape and habitats of value for wildlife with the

maintenance of an efficient supply of good quality food and other products’ (UK government

1994a).

Landscape and habitats are often created or altered incidentally, as the end result of

other resource-use decisions. This makes it very difficult to ensure that the nation’s

environmental capital is not progressively eroded, without careful monitoring and control.

That, in turn, creates many challenges for the agencies responsible for environmental

protection.

Strategies

The traditional approach, certainly in post-war Britain, has been to use a combination

of tools in the quest for an optimum land-use strategy, which would derive the largest

possible benefits from its environmental estate consistent with preserving the ‘natural

capital’ on which it is based. This toolkit includes making special efforts to prevent loss

of specific landscapes features such as hedges and ponds, using planning legislation to

control unsuitable development in natural and semi-natural areas, and designating and

protecting particular landscapes and habitats which have regional, national or

international importance. It also includes working in partnership with landowners and

managers, environmental organisations and groups, and the general public in order to

inform, advise and empower them to play their part in looking after the nation’s

environmental assets.

CONSERVATION AND PRESERVATION

447

Changes in land cover

Results from the 1990 Countryside Survey show some interesting patterns of change in

land cover, many of which have direct or indirect consequences for landscape and habitats.

Land cover in Great Britain remains dominated by arable land, improved grassland and

heath/moorland. But there were net reductions in area under each cover type between 1978

and 1990—the area of arable land fell by 4 per cent, and area under improved grassland fell

by 2 per cent—mainly because of urban development and new woodland. Crop patterns

changed within the arable area between 1978 and 1990, with large increases in the area

used to grow wheat and oilseed rape, a large increase in non-cropped arable land set aside

from productive use, and a corresponding decrease in the area used to grow barley. These

changes have in turn promoted changes in patterns and levels of use of fertilisers and

pesticides, which also benefit wildlife.

Most of the changes in land cover between 1978 and 1990 were concentrated in

lowland landscapes. In the lowlands arable was lost mostly to woodland, urban and semi-

natural land cover types which were partly offset by the conversion of some improved

grasslands to arable. Improved grassland was lost to arable, woodland, urban and semi-

natural cover types. In upland landscapes the area of ‘other semi-natural land’ cover types

fell by 3 per cent, whereas in lowland landscapes it rose by 10 per cent (largely because of

increases in non-agriculturally improved grass, unmanaged tall grassland, and felled

woodland).

Other cover changes between 1984 and 1990 include a major decline in well-managed

grassland and corresponding expansion of weedy grassland (offering more habitat diversity

for wildlife), and further decrease in the small surviving area of heath and moorland in

lowland landscapes (mainly replaced by woodland).

Farmers are traditionally seen as custodians of the landscape, and not surprisingly

their decisions can have significant impacts on landscape and habitats. Many of the

adverse changes in UK landscapes in recent decades are the direct result of the post-

war drive for increased food production that promoted more intensive farming. This

is true particularly in lowland landscapes, where there have been major losses of

features such as hedgerows and walls and semi-natural habitats such as ancient

meadows, heaths and wetlands. But there are a growing number of environmentally

friendly farmers and environmentally friendly farming practices playing significant

roles in maintaining valued landscapes and habitats. Increased environmental

awareness, coupled with reform of the Common Agriculture Policy in 1992, has

reduced some of the incentives to intensify food production and this is encouraging

the improved management of rural land (Bignal and McCracken 1996). Results from

the 1990s Countryside Survey confirm the importance of urban development and new

woodland as drivers of land cover change. Changing agricultural landscapes are

discussed further in Chapter 5.

Arable set-aside

Nature conservation has benefited a great deal from European Union measures designed to

reduce agricultural output, particularly of crops (Baldock 1994). The EC Set Aside Scheme

was first introduced in 1988, and the 1992 reform of the Common Agriculture Policy

CHRIS PARK

448

introduced further measures and incentives. Since the early 1990s the UK government

has introduced a range of measures intended to encourage the environmental

management of set-aside land, which have proved beneficial to both agricultural land

management and rural landscapes and habitats. One such measure was the voluntary

set-aside scheme that was introduced in 1988 and replaced in 1992 by the Arable Area

Payments Scheme (AAPS). Under the scheme participating farmers must set aside at

least 15 per cent of their arable area each year, on a rotation basis. Most arable farmers

have joined the scheme, which gives them financial incentives not to plough up

permanent pasture for arable crops. But the AAPS scheme is proactive, because it

includes compulsory rules designed to maximise the environmental benefits of set-

aside land. Farmers are also offered free advice on how best to manage their set-aside

land to benefit wildlife.

In 1995, there were some 6,400 square kilometres of arable land set aside in Great

Britain, much of it concentrated in eastern England. The net effect has been to reduce the

total area under crops significantly, helping to produce the desired decrease in food output

and increase in habitats more attractive to wildlife.

Habitat fragmentation

Wholesale changes in land cover, particularly those involving complete replacement of one

cover type with another (as happens with urban development), obviously cause major changes

in the visual appearance and ecological value of an area. But problems are also created by

fragmentation rather than wholesale removal, because smaller habitats suffer from

proportionately larger boundary effects (so there is less homogeneous habitat within the

unit) and dispersed habitats reduce seed sources for plants and make it difficult for animals

to move around freely.

Unfortunately there is little nationwide data on the pace and pattern of habitat

fragmentation through time. One of the few examples for which data exist (environmental

indicator r6 in Table 20.4) is the fragmentation of calcareous grassland on chalk in

Dorset. Between 1966 and 1983 this chalk grassland habitat was increasingly fragmented

into more and smaller units, as the margins of surviving areas were progressively

converted to other cover types. Fragmentation appears to have continued into the 1990s,

putting at risk the survival of the existing remnants and further decreasing their ecological

usefulness.

Grassland changes

Grassland of various types covers extensive areas of Britain, and in many areas the grassland

is being converted or altered in ways which are harmful to wildlife. Many types of grassland

within the broad habitat group ‘semi-natural grassland’, for example, are of particular

importance to nature conservation yet they are scattered throughout the country in relatively

small areas, and have been subject to a range of pressures.

A good example is calcareous grassland that grows on soils derived from chalk and

limestone. According to the 1990 Countryside Survey it now covers less than 500 square

kilometres (0.2 per cent of the total land area of Britain). Historical records show that the

area of chalk grassland in Dorset shrank from about 1,170 square kilometres in 1793 to

CONSERVATION AND PRESERVATION

449

about 130 in 1815 (as corn growing replaced sheep grazing), and by the early 1990s it

was down to about 30. The pattern has been repeated in most parts of Britain, so that by

the late 1990s few large areas of chalk grassland remained other than Salisbury Plain and

Porton Down in Wiltshire. Much (60 per cent) of the chalk grassland lost between 1966

and 1984 was ploughed, and most of the rest (32 per cent) was invaded by scrub after

grazing ceased.

Attempts are being made to preserve surviving remnants of such ecologically important

habitats under the two major farmland conservation schemes (Environmentally Sensitive

Areas and Countryside Stewardship, see p. 454). About a third of the remaining calcareous

grassland on chalk is located within Sites of Special Scientific Interest, where it is protected

by appropriate management.

Another type of grassland that has been subjected to change and disturbance is semi-

improved grassland, which owes its origin and character to many generations of farming

use mainly as pasture. Semi-natural grassland is part of this semi-improved grassland

category. In 1990 lowland semi-improved grassland covered an estimated 13 per cent of the

total area of Great Britain, and it supported a wide variety of plant and animal species.

Environmental indicator r3 (Table 20.4) describes changes in plant diversity in semi-improved

grassland.

Results from the Countryside Surveys show a statistically significant reduction

between 1978 and 1990 in plant diversity in semi-improved grasslands, reflecting more

intensive management. This applies both in ‘arable’ landscapes (where the mean number

of species per plot fell from 19.4 to 17.4) and ‘pastural’ landscapes (where it fell from

21.5 to 16.6). Declines were fastest among plants associated with unimproved meadows,

including some rare grassland species. Traditional land management (which does not

use fertilisers and herbicides) seems most appropriate for these cover types, and seems

the most promising way of preserving the diversity of wildlife for which it provides a

habitat.

Preservation of specific features

Many landscape features, particularly in the lowlands, have been radically altered during

the twentieth century either deliberately or through neglect. Hedgerows, stone walls and

ponds and lakes are the most obvious. They are attractive landscape features that add variety

to the appearance of an area, and have helped create the traditional patchwork-quilt mosaic

of many parts of the countryside. But their importance extends beyond the visual, because

each offers important habitats for wildlife. Linear features such as hedges and stone walls

also provide important environmental services as wind-breaks and shelter belts which act

as barriers against soil erosion. Many hedges and stone walls (and to a lesser extent farm

ponds) are also of historical importance. Streams and streamsides also offer important habitats

to wildlife and they can be important components of the visual landscape.

Hedgerows and stone walls

One hallmark of twentieth-century landscape change in the United Kingdom has been radical

change if not wholesale removal of hedges in the countryside. Modern farm machinery is

used most efficiently on large fields, so there has been relentless pressure to uproot traditional

CHRIS PARK

450

hedge field boundaries to create larger working units. Between 1984 and 1990 hedgerow

lengths in Great Britain decreased by an estimated 150,000 kilometres (25,000 per year).

Nearly 87 per cent of the losses (130,000 kilometres in total, 22,000 per year) were in

England and Wales and the rest (20,000 kilometres in total, 3,000 per year) were in

Scotland. Between 1990 and 1993, the net rate of loss of hedgerows in England and

Wales slowed to around 18,000 kilometres per year. Stone walls, another feature in the

traditional farming landscape in many areas, have also been cleared to increase field sizes

and improve farm efficiency. Between 1984 and 1990 the length of stone walls in Great

Britain decreased by 21,000 kilometres from an estimated 214,000 to 193,000 (a rate of

around 3,000 per year).

In the past, deliberate hedge clearance has been the major problem, but many surviving

hedges are now suffering from neglect through lack of maintenance and conversion to other

types of field boundary (particularly fences). Regular hedge management is costly and time

consuming, and it contributes little if anything to the farm economy in the short term. In a

climate of financial constraints within agriculture, hedge management can be suspended

while more pressing problems are tackled. Natural regrowth within the neglected hedge can

quickly turn it into a line of bushes or trees. Between 1984 and 1990 about a third (36 per

cent) of the hedge loss in Britain was due to uprooting, about a quarter (23 per cent) due to

management neglect, and the rest (41 per cent) due to conversion.

Some of the wholesale loss and decline of traditional hedgerows is now being offset by

the restoration of degraded hedges and planting of new ones. Creation and proper management

of hedgerows and stone walls is being promoted under the Countryside Stewardship Scheme

and regulated under Section 97 of the Environment Act 1996. Results from a 1993 survey for

England and Wales indicate that more hedges are being planted than uprooted— the rate of

new planting exceeded the rate of removal by around 800 kilometres per year between 1990

and 1993. New hedges take many years to become fully established, but in the medium to

long term they will increase the diversity of habitats for wildlife within the countryside.

But it is not just the quantity of linear features such as hedges and stone walls that

matters to conservation, their quality is also vitally important. Field boundaries provide

important habitats for birds, mammals and plants that are often rare locally, so they serve as

reservoirs of biodiversity. They also provide seed banks of locally native plants, which

under suitable conditions might allow natural regeneration of species-rich habitats in the

future. Environmental indicator r5 (Table 20.4) records the changes in mean species numbers

in linear plots recorded as hedgerows in 1978, based on 202 hedge plots sampled in 1978

and reliably relocated and recorded in the 1990 Countryside Survey. The 188 hedges that

remained in 1990 supported high species diversity, although the number of species for

hedge plots in ‘pastural’ landscapes fell significantly between 1978 and 1990. This was true

particularly of plants associated with meadow and chalk grasslands, reflecting a move towards

more intensively managed vegetation. There was no significant change in the species diversity

of hedges in lowland ‘arable’ landscapes, although the survey shows a change towards

plants more characteristic of arable fields.

Ponds and lakes

Lakes and ponds (water bodies generally smaller than about 2,000 square metres in area)

are characteristic features of the landscape in many part of the United Kingdom, even though

CONSERVATION AND PRESERVATION

451

many of the smaller ones were artificially created. They provide important wildlife habitats,

offering opportunities for aquatic species in what are essentially terrestrial landscapes. Many

species of plants and animals live in the water or at the water’s edge, or use them during

their life cycle. In the past ponds were common on farms because they provided water for

livestock, but many have been drained or filled in because they serve no practical purpose to

modern farming.

Environmental indicator r7 (Table 20.4) provides estimates of the numbers of lakes

and ponds in Great Britain between 1945 and 1990. Although the two surveys are not directly

comparable, the results suggest a 30 per cent decrease in the number of static inland water

bodies from about 470,000 in 1945 to about 330,000 in 1990. A survey by the Institute of

Terrestrial Ecology estimates that between 4 and 9 per cent of water bodies disappeared

between 1984 and 1990 (partly following the 1990 drought). The same survey suggests a 6

per cent fall in the number of ponds, which accounts for more than 90 per cent of the water

bodies recorded in 1990.

As with hedgerows, this trend of decline has been ongoing since at least the mid-

1940s, reflecting changing farming practices and more intensive land-uses. But the decline

might be slowed down or even halted if a number of initiatives taken since the late 1980s

prove to be successful. The two most important of these are changes in the Common

Agriculture Policy (away from continued intensification of production) and the introduction

of more environmental land management schemes (see p. 454).

Streams and stream-sides

There are more than 250,000 kilometres of rivers and streams in England and Wales, and

both the waterways and their banks provide important habitats for wildlife and add variety

to landscape. Whilst some rivers have been studied intensively, until recently nationwide

evidence about river habitats has been patchy. The Environment Agency has established a

River Habitat Survey (RHS) to provide a national inventory, based on 500 randomly selected

lengths of river throughout England and Wales. Initial results indicate that only about 9 per

cent of the river lengths are unmodified.

Water quality is regularly measured at a large number of sites by the Environment

Agency to determine the scale and pattern of water pollution across the country (see Chapter

18.2). Biological indicators are another useful way of evaluating environmental quality,

and the presence or absence of otters offers a good indication of freshwater quality. A survey

of the distribution of otters in Great Britain was made in 1993, and it shows that otters are

returning to many river systems (including the Severn, Avon and Teme) as water quality

improves. The Environment Agency is encouraging this natural process of ecological recovery

by taking steps to protect existing populations and facilitating the recolonisation of new

stretches of river.

Like hedgerows, lakes and ponds, stream banks provide habitats for many plant and

animal species and they offer important reservoirs of biodiversity. Stream banks are often

affected by river management schemes (such as straightening and dredging), so the quality

of bank habitats is not necessarily a reflection of water quality within the river.

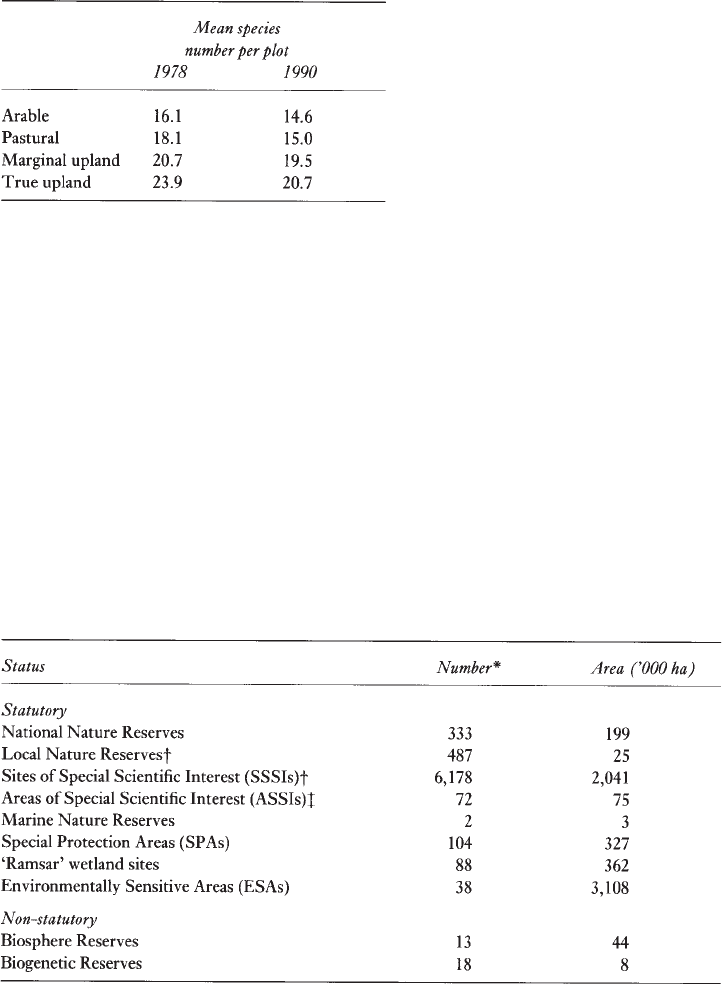

The 1990 Countryside Survey provides useful information on changes in plant diversity

in stream-sides (environmental indicator r8 in Table 20.4) between 1978 and 1990, based

on 322 sample plots in four landscape types. Stream-side plant diversity (Table 20.5) is

CHRIS PARK

452

generally higher in upland landscapes,

and it declined for all four landscape

types between 1978 and 1990. The

decline was statistically significant in

‘pastural’ and ‘true upland’ landscapes.

Species typical of wet meadows and

moist woodlands appear to have

declined more than most other stream-

side species. Some of the decline might

be caused by the 1990 drought, but that

would not explain why losses also

occurred in upland streams (which were

not affected by the drought) and why most of the species that disappeared were long-lived

perennials.

Non-statutory protected land

The adoption of more environmentally friendly practices by farmers and encouragement to

preserve particular features such as hedges, ponds and lakes, and stream-sides are extremely

important to wildlife conservation and landscape preservation in the United Kingdom. But

they must be seen as part of a broad approach to the problem of sustainable development

(Adams et al. 1994). Another key ingredient in this multi-faceted approach is to designate

particular areas of land for specific protection. Within them natural resources can be more

effectively managed, specifically to preserve and enhance habitats and landscape, and

potentially damaging cover changes or development can be properly handled. Within the

TABLE 20.5 Changes in plant diversity in streamsides,

Great Britain, 1978–90

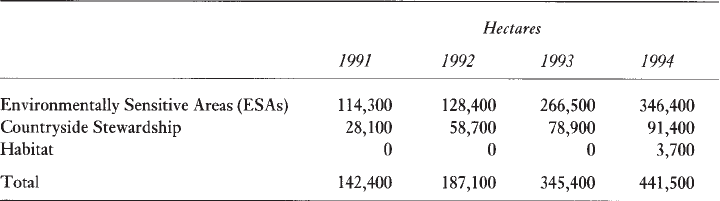

TABLE 20.6 Protected areas in the United Kingdom as at 31 March 1995

Notes: *Some areas may be included in more than one category.

†Great Britain only.

‡Northern Ireland only.

CONSERVATION AND PRESERVATION

453

UK these protected areas fall into two groups—those which form the statutory system (set

up and controlled under legislation), and non-statutory areas.

The non-statutory areas are usually owned by the agency which establishes them,

they are carefully managed, and public access (sometimes under controlled conditions) is

generally encouraged (Box et al. 1994). Typical of such areas are the estates and land

owned and managed by the National Trust in England and Wales, which cover a total area

of around 2,390 square kilometres. Many have historical connections, most attract large

numbers of visitors, and the National Trust invests a great deal of resources in managing

and restoring habitats (Hearn 1994). Another important group of non-statutory areas are

the seventy-six nature reserves (total area 487.83 square kilometres) managed by the

Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB), and the 1,870 smaller reserves (total

area 360 square kilometres) owned or managed by the Royal Society for Nature

Conservation. In addition there are also the 4,000 square kilometres or so of woodlands

managed by Forest Enterprise (formerly the Forestry Commission) in England and Wales,

of which 40 per cent (1,600 square kilometres) are Forest Parks. Public access is allowed

(on foot) to all of the forest and woodland areas.

There are two other important categories of non-statutory protected areas in the UK

(Table 20.6) —thirteen Biosphere Reserves (covering a total of 440 square kilometres) and

eighteen Biogenetic reserves (covering a total of 80 square kilometres). These are part of an

international programme of nature conservation and sustainable development. Each reserve

is designed to protect unique areas and their wildlife, but they are also used for research,

monitoring, training and demonstration of best conservation practice (Price 1996).

Protected areas and statutory protected land

Large areas of rural land in the United Kingdom are protected because of their special

interest, their importance as landscape or their value as wildlife habitat. Most are protected

under national or international legislation, hence they are described as statutory. As outlined

below, a range of designations has been introduced which offer different levels and types of

protection. Some designations are designed primarily to protect landscape, while others are

designed primarily to protect habitats (Idle 1995). Inevitably both types of designation

benefit both landscape and wildlife, although tensions are often created in setting objectives

and priorities within each.

It is sometimes wrongly assumed that designated areas are given unlimited protection,

but in a crowded country like the UK there is usually pressure to allow appropriate types of

activity to take place within the designated areas. ‘Appropriate’ in this sense does not simply

mean non-damaging or environmentally friendly, because in some cases—such as the

National Parks—maintenance of the character of a landscape is conditional upon continued

economic activity. Clearly much tighter controls on development are appropriate in some

designations, such as nature reserves. Throughout the system of designated areas within the

United Kingdom, however, difficult decisions are required which balance the need to protect

environment against the need for optimal use of available resources. This tension lies at the

very heart of sustainable development.

All sites designated for landscape preservation or wildlife conservation are defined

and delimited on the basis of the best available appropriate scientific information. Periodic

reviews are undertaken to evaluate whether designations, site boundaries and management

CHRIS PARK

454

strategies need to be revised in the light of new information (e.g. about habitat condition or

species diversity), changing circumstances, and changing objectives (including the need to

comply with international agreements). Consequently the inventory of designated sites is

never static.

Environmentally managed land

One part of the government’s proactive approach to sustainable development of the

countryside has been the introduction of a range of environmental management schemes,

some designed to encourage more extensive farming methods. The two most important of

these are the Environmentally Sensitive Areas (ESA) scheme and the Countryside

Stewardship scheme. Both are voluntary schemes that offer landowners financial incentives

to manage their land in more environmentally friendly ways. The objective is to conserve

and where possible recreate valued landscapes and wildlife habitats, to offset some of the

more environmentally damaging aspects of modern intensive farming. Particular attention

is paid within both schemes to promoting better management of landscape features such as

hedgerows and traditional stone walls.

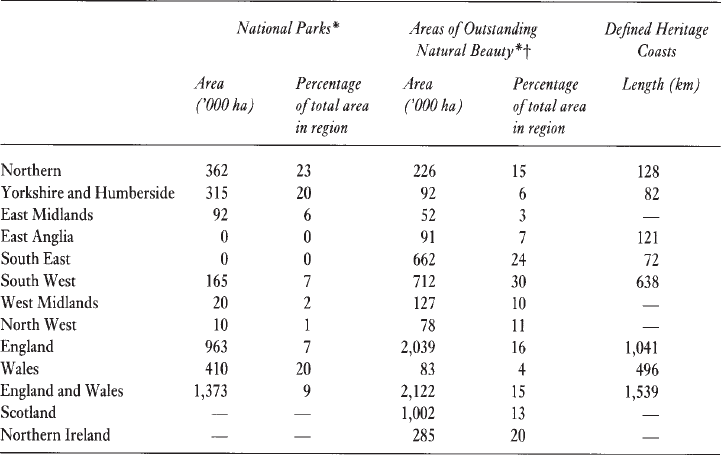

The Environmentally Sensitive Areas (ESA) scheme was introduced in 1987 with the

objective of protecting particular areas of England whose environments are regarded as

nationally important, and whose conservation depends on adopting, maintaining or extending

particular farming practices (Perkins 1996). ESAs are designated on the recommendations

of the relevant conservation bodies (such as English Nature). Under the scheme landowners

(including farmers) receive annual payments under voluntary ten-year management

agreements to implement particular agricultural practices such as the traditional management

of hay meadows. The area under ESAs (Table 20.7) trebled between 1991 and 1994 from

1,140 to 3,460 square kilometres.

The ESA scheme is complemented in England by the Countryside Stewardship scheme,

which was introduced in 1991 to promote the conservation of landscape types outside ESAs.

Between 1991 and 1994 the area of land covered by the Countryside Stewardship scheme

(Table 20.7) more than trebled from 280 to 910 square kilometres. In October 1995 the

government announced its intention (in the Rural White Paper) to increase funding for the

Countryside Stewardship scheme. This would allow the scope of the scheme to be broadened

to include (amongst other things) grant support for management of traditional stone walls

and banks, and for conserving the remaining unimproved areas of old meadow and pastures

on neutral and acid soils throughout lowland England.

TABLE 20.7 Environmentally managed land in England, 1991–4

CONSERVATION AND PRESERVATION

455

By 1994, some 4,400 square kilometres of land in England—around 4 per cent of the

total agricultural land area—was covered by management agreements under the ESA and

Countryside Stewardship Schemes (Table 20.7).

Landscape designations

The most important designations for preserving landscape are National Parks, Areas of

Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, and National

Scenic Areas (NSA) in Scotland (Table 20.8) (Figure 20.1).

National Parks

There are ten National Parks in England and Wales, established under the 1949 National

Parks and Access to the Countryside Act (Curtis 1991). Each serves both conservation

and recreational functions, and each contains a mixture of land cover and includes

settlements, extractive industries and farming. Nearly a quarter of the Northern Region

lies within National Parks (Table 20.8), whereas the South East and East Anglia have

none although the Broads of East Anglia have a separate status equivalent to that of a

National Park, and the New Forest in Hampshire has special protection in law. The ten

TABLE 20.8 Designated areas in the United Kingdom, by region, at December 1995

Notes: Some areas may be in more than one category, and areas are estimated.

*Figures shown may differ from those previously published due to redefinition or remeasurement of

some National Parks and AONBs.

†National Scenic Areas in Scotland.