Egerton R.F. Electron Energy-Loss Spectroscopy in the Electron Microscope

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

298 5 TEM Applications of EELS

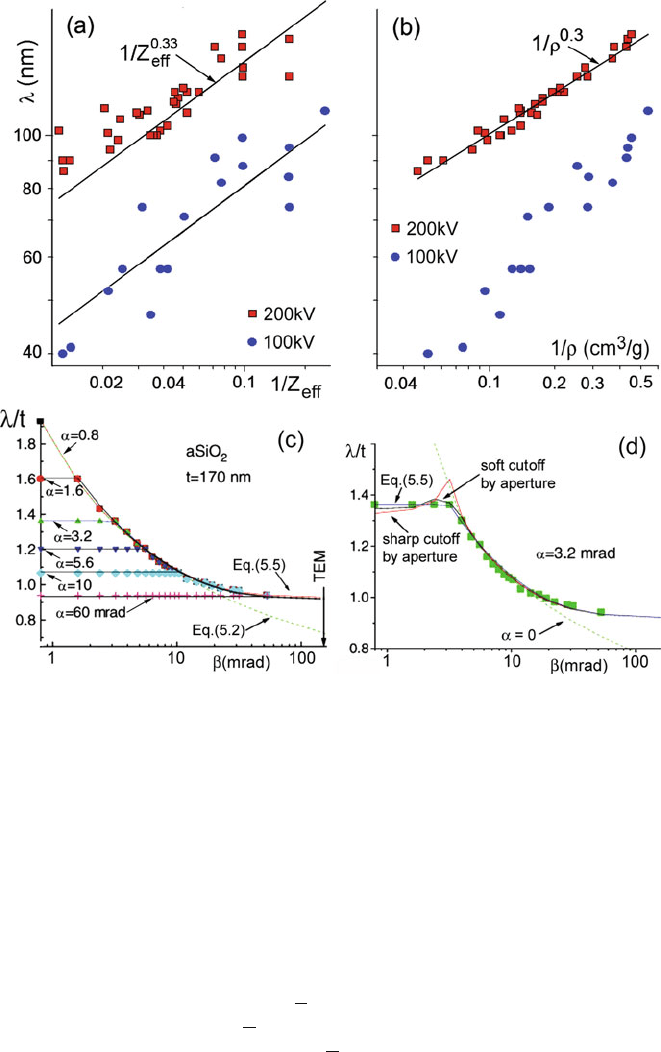

Fig. 5.2 Log–log plot of inelastic mean free path (for large β) as a function of (a) effective atomic

number Z

eff

and (b)densityρ of the specimen. Note the smaller amount of scatter in the latter

case. Squares represent values measured by Iakoubovskii et al. (2008b)atE

0

= 200 keV. Filled

circles are for E

0

= 100 keV and are derived from Eq. (5.2) by scaling to large collection angle by

the use of Eq. (3.16).(c) Measured inelastic mean free path λ for SiO

2

as a function of collection

semi-angle β and incident beam convergence angle α.Thevertical arrow shows the limit to β

imposed by the lens bore of a typical TEM. (d) Collection angle dependence of λ for α = 3.2

mrad. From Iakoubovskii et al. (2008a), copyright Wiley

and β are below the cutoff angle θ

c

, taken in Eq. (5.6) to be 20 mrad. The measured

α- and β-dependence of λ are shown for amorphous SiO

2

in Fig. 5.2c, d, together

with the parameterized formula, Eq. (5.5). Note that the value of λ is essentially

determined by the larger of α and β.

Equation (5.5a) implies θ

E

= E/(γ m

0

v

2

), where

¯

E represents some mean

energy loss, whereas θ

E

= E/(m

0

v

2

) relativistically; see Appendix A.Thisis

arguably a worse choice than θ

E

≈ E/(2E

0

) as assumed in Eq. (5.2), since

5.1 Measurement of Specimen Thickness 299

Fig. 5.3 Inelastic mean free

paths for elemental solids at

β = 10 mrad. Equation (5.5)

is represented by filled circles

at 200 keV and by open

circles at 100 keV. Equation

(5.2) is represented by a solid

line at 200 keV and a broken

line at 100 keV

(γ m

0

v

2

/2) = γ FE

0

= 172 keV at E

0

= 200 keV, whereas FE

0

= 124 keV.

The E

0

scaling of Iakoubovskii’s Eq. (5.5) might therefore be improved by replac-

ing F in Eq. (5.5a)byF

g

= γ F. Note that Eq. (5.5a) implies

¯

E ≈ 11ρ

0.3

, whereas

Eq. (3.41a) gives E

p

∝ (zρ/A)

1/2

for the free-electron plasmon energy.

The main differences between Eqs. (5.2) and (5.5) are that the Iakoubovskii mean

free paths show pronounced oscillation with atomic number and are on average a

factor 1.4 (at 200 keV) or 1.3 (at 100 keV) larger than those given by the Malis et al.

formula; see Fig. 5.3.

Bonney (1990) reported that Eq. (5.2) gave thickness to within 10% when tested

on sub-micrometer vanadium spheres whose thickness was taken to be the same

as their diameter. The 100-keV measurements of Crozier ( 1990) are also within

±15% of the Malis et al. (1988) formula. The parameterization of Iakoubovskii

et al. (2008a) more accurately reflects the Z-dependence of Crozier’s measurements

but overestimates the absolute values by an average of 25%; see Fig. 5.4.

Fig. 5.4 Solid data points:

inelastic mean free path for

C, Al, Fe, Cu, Ag, and Au

(for E

0

= 100 keV, β = 5,

21, and 120 mrad) as

measured by Crozier (1990).

Hollow data points show

values predicted by Eq. (5.6),

the full and dashed lines are

the predictions of Eq. (5.2)

300 5 TEM Applications of EELS

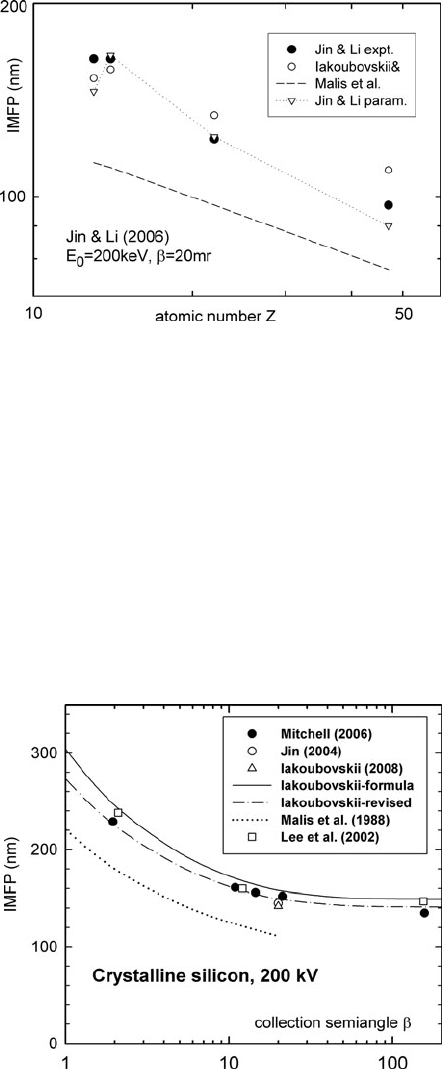

Fig. 5.5 Solid circle:

inelastic mean free path of

Al, Si, Ti, and Ag (for

E

0

= 200 keV, α = 10 mrad,

and β = 20 mrad) measured

by Jin and Li (2006). Hollow

circles: values predicted from

Eq. (5.6). Dashed line:Eqs.

(5.2)and(5.3). Inverted

triangles:Eq.(5.2) with

E

m

= 43.5Z

0.47

ρ/A

Figure 5.5 shows 200-keV measurements of Jin and Li (2006). Here the

Iakoubovskii et al. (2008a) formula matches the experimental data within 10%. The

dipole approximation is not valid for this data, so the Malis et al. (1988)formula

underestimates λ. Jin and Li obtained a good fit to their data by replacing Eq. (5.2a)

by E

m

= 43.5 Z

0.47

ρ/A where A represents atomic weight.

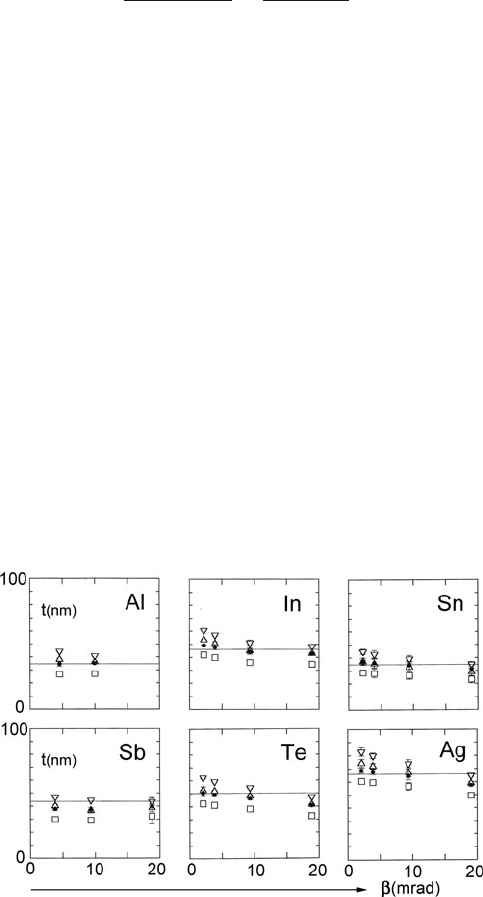

Figure 5.6 shows 200-keV measurements on silicon, all within 10% of the

Iakoubovskii formula (solid curve) at medium values of β. The agreement is

improved further (dash-dot curve) by replacing F in Eq. (5.5a)byF

g

= γ F.

For most materials, the Iakoubovskii et al. (2008a) parameterization of λ appears

to represent an improvement over that of Malis et al. (1988) in terms of the accu-

racy, convenience of use (requiring density rather than an E

m

value), and the fact

Fig. 5.6 Inelastic mean free

path for crystalline silicon as

a function of collection

semi-angle. Data points

represent TEM

measurements. The dash-dot

curve represents Eq. (5.5)

with F in Eq. (5.5a) replaced

by F

g

5.1 Measurement of Specimen Thickness 301

that the formula should apply to large β (e.g., 100 mrad, limited only by post-

specimen lenses). Advantages of large β are that its exact value need not be known

and convergence correction is unnecessary, so the incident probe convergence α is

not required. The programs IMFP and PMFP, described in Appendix B, calculate λ

for the different formulas described above.

Although Eq. (5.1) involves specimen thickness t, it is actually the total scat-

tering and mass thickness that is measured by EELS. If the physical density of a

material were reduced by a factor f, the scattering per atom would remain the same

(according to an atomic model) and the mean free path should increase by a factor f.

This prediction was confirmed by Jiang et al. (2010), using crystalline MgO and

nanoporous MgO whose density was about half the bulk value, resulting in a mea-

sured λ about a factor of 2 l arger. Such arguments ignore the presence of surface

plasmon losses at internal pores, and as pointed out by Batson (1993a) the presence

of surfaces increases the total scattering, despite the begrenzungs effect (Fig. 3.25).

In practice, this increase appears to be modest. Shindo et al. (2005) measured mean

free paths differing by a factor ≈1.7 for diamond-like carbon films prepared by

different methods, with physical densities between 1.4 and 2.1 g/cm

3

.

5.1.1.2 Organic Specimens

Biological specimens vary in porosity and are usually characterized in terms of mass

thickness ρt, which can be determined from a variant of Eq. ( 5.1), namely

ρt = ρλ ln(I

t

/I

0

) = (1/σ

)ln(I

t

/I

0

) (5.6)

where σ

is a cross section per unit mass. Calculations of Leapman et al.

(1984a, b) based on Thomas–Fermi, Hartree–Fock, and dielectric models (Ashley

and Williams, 1980) suggested that ρλ varies by no more than ±20% for biologi-

cal compounds, although these different models predicted values of ρλ differing by

almost a factor of 2 (e.g., 8.8 μg/cm

2

to 15 μg/cm

2

for protein at E

0

= 100 keV).

Other measurements and calculations based on the Bethe sum rule gave ρλ =

17.2 μg/cm

2

for protein at 100-keV beam energy (Sun et al., 1993).

The only data processing involved in the log-ratio method is separation of the

spectrum into zero-loss and inelastic components, both of which are strong signals

and relatively noise free. Measurements can therefore be performed rapidly, with

an electron exposure of no more t han 10

−13

C. Even for organic materials, where

structural damage or mass loss can occur at a dose as low as 10

−3

C/cm

2

, thickness

can be measured with a lateral spatial resolution below 100 nm. In this respect, the

log-ratio technique is an attractive alternative to the x-ray continuum method (Hall,

1979), which requires electron exposures of 10

−6

C or more to obtain adequate

statistics (Leapman et al., 1984a). Rez et al. (1992) employed the log-ratio method to

measure the thickness of paraffin crystals, with a reported accuracy of 0.4 nm under

low-dose (0.003 C/cm

2

) and low-temperature (−170

◦

C) conditions. Leapman et al.

(1993a) used similar methods to measure 200-nm-diameter areas of protein (cro-

toxin) crystals and achieved good agreement with thicknesses determined using the

302 5 TEM Applications of EELS

STEM annular dark-field signal, after correcting the latter for nonlinearity arising

from plural elastic scattering.

Zhao et al. (1993) measured t/λ for a biological thin section by fitting its carbon

K-edge to a sum of components derived from K-loss and plasmon-loss single-

scattering distributions, both recorded from a pure carbon film, giving a “carbon

equivalent” thickness. This procedure is convenient to the extent that it does not

require recording of the low-loss region of the thin section, but it involves a radiation

dose about 100 times higher than that required by the log-ratio method.

5.1.2 Absolute Thickness from the K–K Sum Rule

As described in Section 4.2, Kramers–Kronig analysis of an energy-loss spectrum

gives a value for the absolute specimen thickness, along with energy-dependent

dielectric data, without requiring the chemical composition of the specimen. The

procedure involves extraction of the single-scattering distribution S(E) from a mea-

sured spectrum, use of the Kramers–Kronig sum rule to derive the energy-loss

function Im[−1/ε(E)], and removal of the surface scattering component of S(E)by

iterative computation; see Appendix B.

If specimen thickness is the only requirement, the procedure can be simplified.

Combining Eqs. (4.27) and (4.26)gives

t =

4a

0

FE

0

I

0

{1 −Re[1/ε(0)]}

∞

0

S(E)dE

E ln(1 + β

2

/θ

2

E

)

(5.7)

where a

0

= 0.0529 nm, F is the relativistic factor given by Eq. (5.2a), and

θ

E

is the characteristic angle defined by Eq. (3.28). In general, Re[1/ε(0)] =

ε

1

/(ε

1

2

+ε

2

2

)

2

, where ε

1

and ε

2

are the real and imaginary parts of the optical

permittivity. However, as discussed in Section 4.2,Re[1/ε(0)] can be taken as zero

for a metal or semimetal and as 1/n

2

for an insulator or semiconductor of refractive

index n.

The 1/E weighting factor makes the integral in Eq. (5.7) less sensitive to higher

orders of scattering. Provided the specimen is not too thick (t/λ < 1.2), the effect of

plural scattering can be approximated by dividing the integral by a correction factor

(Egerton and Cheng, 1987)

C ≈ 1 + 0.3(t/λ) = 1 + 0.3 ln(I

t

/I

0

) (5.8)

Kramers–Kronig analysis carried out on thin films of A1, Cr, Cu, Ni, and Au

(Egerton and Cheng, 1987) suggested that a more accurate value of thickness is

obtained by subtracting an amount t (≈8 nm) from the value given by Eq. (5.7)

to allow for surface plasmon scattering. With these approximations, and assuming

β

2

/θ

E

2

>> 1 over the energy range where the inelastic intensity is significant,

Eq. (5.7) can be simplified to

5.1 Measurement of Specimen Thickness 303

t =

2a

0

T

CI

0

{1 −n

−2

}

∞

0

J(E)dE

E ln(β/θ

E

)

−t (5.9)

Here J(E) represents the inelastic component of the energy-loss spectrum, including

plural scattering but excluding the zero-loss peak. A computer program (TKKs) that

evaluates Eq. (5.9) is described in Appendix B.

Because of the 1/E weighting in Eq. (5.9), the value of t is particularly sensitive

to data at very low energy loss. The procedure used to separate the elastic scattering

peak from the inelastic intensity is therefore important. The simplest method is to

truncate the spectrum at the first minimum, E = δ in Fig. 5.1, but it results in

an underestimation of t (square data points in Fig. 5.7), since contributions below

E = δ are missing. Omitting the surface correction, by setting t to zero in Eq. (5.9),

compensates for this missing contribution and gives a more realistic thickness value

(solid circles in Fig. 5.7). Linear or parabolic extrapolation of the inelastic intensity

(at E = δ) to zero (at E = 0) also gives acceptable r esults (triangles in Fig. 5.7).

Another strategy is to model the tail of the zero-loss peak and subtract this from the

spectrum to give the inelastic intensity J(E).

The errors involved in these procedures can be minimized by optimizing the

energy resolution. Spectra read out from a CCD camera should be recorded with

a sufficiently high energy dispersion (low electron volt/channel) to minimize the

energy range over which tails of the zero-loss peak are significant, even though this

results in spectra with a restricted energy range. Because of the 1/E weighting in

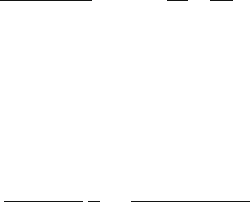

Fig. 5.7 Thickness (in nm) of Al, In, Sn, Sb, Te, and Ag films measured using the Kramers–Kronig

sum rule with different treatments of the low-energy limit (Yang and Egerton, 1995). Inverted and

upright triangles denote linear and parabolic interpolation (respectively) between the origin and

the first intensity minimum. Eliminating data below the minimum gave values represented by the

squares and solid circles, the surface term t being set to zero in the latter case. Horizontal lines

represent the film thickness determined by weighing, assuming bulk densities

304 5 TEM Applications of EELS

Eq. (5.9), the upper limit of integration can be as low as 100 eV for reasonably

thin specimens. If t/λ > 1.2, the plural scattering correction in Eq. (5.9) becomes a

poor approximation. A better procedure is then to use Fourier log deconvolution to

remove the plural scattering component and employ Eq. (5.9) with C = 1.

Because the Kramers–Kronig procedure is based on the equivalence of energy

loss and optical data, the spectral intensity J(E) must be dominated by dipole scat-

tering, implying a small collection semi-angle β (which must be known). In practice,

values up to 18 mrad give acceptable results at E

0

= 100 keV (Fig. 5.7); at 200 keV,

this condition becomes β < 10 mrad.

Iakoubovskii et al. (2008a) found good agreement between thicknesses obtained

from the K–K sum rule (with E

0

= 200 keV, β

∗

≈ 12 mrad) and those deduced

from convergent-beam diffraction. These measurements were used to derive inelas-

tic mean free paths for many elements and oxides (Iakoubovskii et al., 2008b); see

Appendix C.

The advantage of the K–K sum rule method is that it gives thickness without

knowledge of the material properties of the specimen, if the latter is conducting

so that Re[1/ε(0)] ≈ 1 − n

−2

≈ 0. In the case of semiconducting and insulating

specimens, an optical permittivity or refractive index n is required, and in the case

of nanoporous materials, n will be reduced because of the lower physical density.

5.1.3 Mass Thickness from the Bethe Sum Rule

As in Section 3.2.2, the single-scattering intensity S(E) can be written in terms of a

differential oscillator strength df/dE rather than the energy-loss function Im(−1/ε).

Combining Eqs. (3.33) and (4.26)gives

S(E) =

4πI

0

Na

2

0

R

2

FE

0

E

ln

1 +

β

2

θ

2

E

df

dE

(5.10)

where N is the total number of atoms per unit area and df/dE is a dipole (small-q)

oscillator strength. Taking all the E-dependent terms to the right-hand side of this

equation, integrating over energy loss, and making use of t he Bethe sum rule of

Eq. (3.34),wehave

ρt = ANu =

uFE

0

4πa

2

0

R

2

I

0

A

Z

∞

0

ES(E)

ln

,

1 +β

2

/θ

2

E

-

dE (5.11)

where u is the atomic mass unit and ρt is the mass thickness of the specimen, A and

Z being its atomic weight and atomic number. For a compound, A is replaced by the

molecular weight and Z by the total number of electrons per molecule.

The integral in Eq. (5.11) is relatively insensitive to the instrumental energy res-

olution, allowing S(E) to be taken as the intensity J

1

(E) obtained from Fourier log

deconvolution of experimental data. The combined effect of the other terms within

5.1 Measurement of Specimen Thickness 305

the integral is to weight S(E) by a factor typically between E and E

2

, implying

that the spectrum must be measured up to rather high energy loss to ensure conver-

gence of the integral. Convergence is further delayed because inner atomic shells

contribute to S(E) at energy losses above their binding energy. This means that

Eq. (5.11) is useful only for specimens composed of light elements, with K-shell

binding energies below 1000 eV. However, this category includes most organic and

biological materials, containing mainly carbon, oxygen, and hydrogen. Figure 5.8

shows the E-dependence of Eq. (5.11) for pure carbon, where the integral reaches

its saturation value at about 1000 eV.

The need for such an extended energy range means that the spectrum must be

recorded in segments with different integration times and spliced together. Because

the intensity is integrated in Eq. (5.11), good statistics and energy resolution are

not important and the high-E data can be quite noisy. However, any detector back-

ground (dark current) must be carefully removed, together with any spectrometer

background that arises from stray scattering, as discussed in Chapter 2. Unless

the specimen is extremely thin, plural scattering should be removed by Fourier log

deconvolution.

For light elements, the ratio A/Z in Eq. (5.11) is close to 2, but a better approx-

imation for most biological materials is to take A/Z = 1.9 (Crozier and Egerton,

1989), in which case Eq. (5.11) can be rewritten as

ρt =

BE

0

I

0

(1 +E

0

/1022)

(1 +E

0

/511)

2

∞

0

EJ

1

(E)

ln

,

1 +β

2

/θ

2

E

-

dE (5.12)

where B = 4.88 × 10

−11

g/cm

2

E is in eV, and E

0

in keV. This equation was

tested on thin films of copper phthalocyanine (ρt up to 30 μg/cm

2

, corresponding

to t/λ ≈ 1.5) and yielded mass thickness values within 10% of those determined

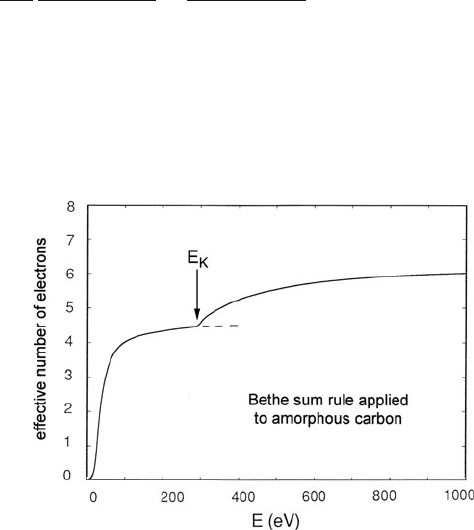

Fig. 5.8 Value of the integral

in Eq. (5.11), expressed as an

effective number of

contributing electrons defined

by Eq. (4.33). Note that n

eff

almost saturates as E

approaches the K-shell

binding energy (284 eV) but

approaches its full value (6)

only for energy losses around

1000 eV. From Sun et al.

(1993), copyright Elsevier

306 5 TEM Applications of EELS

by weighing (Crozier and Egerton, 1989). The Bethe sum r ule has also been used to

determine the cross section per unit mass of protein and water (Sun et al., 1993).

The Bethe sum rule method involves an electron exposure (typically 10

−10

Cfor

parallel recording) higher than that needed to apply the log-ratio method (≈10

−13

C) but its potential accuracy is higher. The bremsstrahlung continuum method (Hall,

1979) is useful for thicker specimens (t >0.5μm) but involves an electron exposure

of the order of 10

−6

C, sufficient to cause significant mass loss in most organic

materials if the diameter of the incident beam is less than 1 μm (Leapman et al.,

1984a).

With suitable calibration, local mass thickness can also be obtained by integrat-

ing the inelastic scattering over chosen ranges of scattering angle and energy loss,

using an electron spectrometer to reject the elastic and unscattered components (Feja

et al., 1997). This may be a lower dose alternative to measuring high-angle elastic

scattering with a STEM and ADF detector (Wall and Hainfeld, 1986; Feja and Aebi,

1999).

5.2 Low-Loss Spectroscopy

The 1–50 eV region of the energy-loss spectrum contains peaks that arise from

inelastic scattering by outer shell electrons. In most materials, the major peak can be

called a plasmon peak; its energy is related to valence electron density and its width

reflects the damping effect of single-electron transitions (Section 3.3.2). In some

cases, these transitions appear directly in the low-loss spectrum as peaks or fine

structure oscillations superimposed on the plasmon peak. The low-loss spectrum

is then characteristic of the material present within the electron beam and can be

used to identify that material, if suitable comparison standards are available and the

spectral data have a sufficiently low noise level.

5.2.1 Identification from Low-Loss Fine Structure

If a specimen contains regions that give rise to sharp plasmon peaks, the materials

involved are easily identified, as demonstrated for metallic sodium, aluminum, or

magnesium by Sparrow et al. (1983) and Jones et al. (1984). Other materials are

harder to characterize because their plasmon peaks are broad and occur within a

limited range, typically 15–25 eV, yet by careful comparison with low-loss spectra

recorded from candidate materials, it is sometimes possible to identify an unknown

phase. This fingerprinting method was used to identify 25–250 nm precipitates

in internally oxidized Si/Ni alloy as amorphous SiO

2

(Cundy and Grundy, 1966)

and 10–100 nm precipitates in silicon as SiC (Ditchfield and Cullis, 1976). More

recently, Evans et al. (1991) quantified the depth profile of aluminum in spinel

implanted with 2-MeV Al

+

ions, the depth-dependent low-loss spectrum being fitted

to reference spectra of aluminum and spinel; see Fig. 5.9.

5.2 Low-Loss Spectroscopy 307

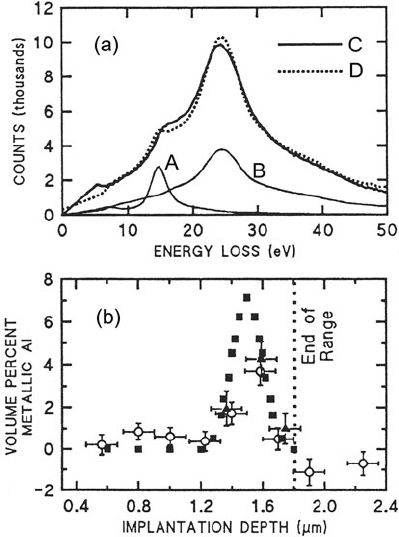

Fig. 5.9 (a) Low-loss spectra

with plural scattering

removed: A = metallic Al, B

= undamaged spinel, C =

material at implant depth of

1.6 μm, D = best fit from

multiple regression analysis,

indicating 3.7 ±0.6 vol.% Al.

(b) Profile showing aluminum

concentration as a function of

depth. From Evans et al.

(1991), with permission from

San Francisco Press, Inc

Because of plural scattering, the overall shape of the low-loss spectrum depends

on specimen thickness, so to avoid errors due to thickness differences between

unknown and reference materials, plural scattering should be removed, for example,

by Fourier log deconvolution. A published library allows comparison of low-loss

spectra with those of some common materials and is now available in digital form

(Ahn, 2004).

Plasmon peak width can sometimes be indicative. Chen et al. (1986)showed

that the plasmon peak measured from quasi-crystalline Al

6

Mn was wider (3.1 eV)

than that of the amorphous (2.4 eV) or crystalline phases (2.2 eV), suggesting that

the icosahedral material had a distinct electronic band structure, favoring plasmon

decay via interband transitions. On the other hand, Levine et al. (1989) found the

plasmon widths of icosahedral Pd

59

U

21

/Si

20

and Al

75

Cu

15

V

10

to be the s ame as

those of amorphous materials of the same composition.

Many organic compounds provide a distinctive fine structure at energies below

the main plasmon peak (Hainfeld and Isaacson, 1978); see Fig 5.10.Evenifthe

structure is not prominent, a careful comparison using multiple least-squares fit-

ting can allow the composition to be measured. Sun et al. (1993) used this method

to determine the water content of cryosectioned red blood cells as 70 ± 2%,

with water and frozen solutions of bovine serum albumin (BSA) as standards.

Acceptable statistical errors in the MLS fitting were obtained with an electron dose