Egerton R.F. Electron Energy-Loss Spectroscopy in the Electron Microscope

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

288 4 Quantitative Analysis of Energy-Loss Data

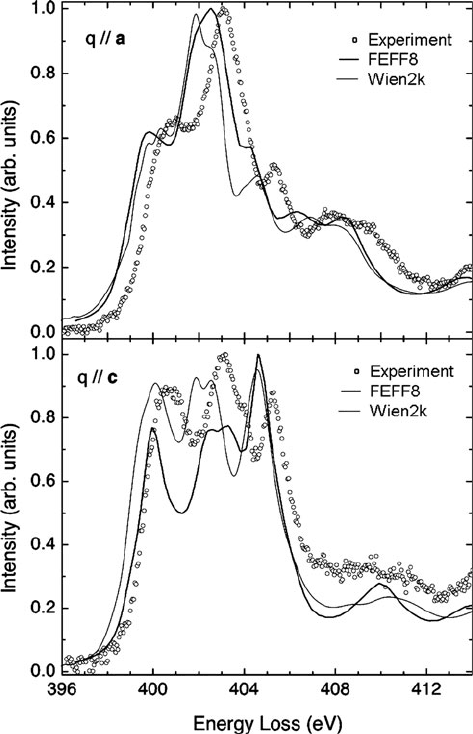

Fig. 4.26 (a) Nitrogen K-edge for h-GaN calculated by FEFF using different numbers of atomic

shells. (b) 42-shell result compared with experiment (open circles). (c) K-edge calculated with and

without a core hole, compared with experiment. From Moreno et al. (2007), copyright Elsevier

were necessary to achieve a reasonable matching with high-resolution (0.2 eV)

EELS data; see Fig. 4.26b.

Orientation dependence (anisotropy) is accommodated for XANES calculations

through a POLARIZATION card; see Fig. 4.27. XANES calculations are done only

for forward scattering but the ELNES card of FEFF9 makes allowance for the size of

the collection aperture, incident beam convergence, relativistic cross sections, and

sample/beam orientation. Allowance is made for an off-axis collection aperture and

quadrupole transitions can be included via the MULTIPOLE card. Thermal vibra-

tions can be added via the DEBYE card but are important only for higher specimen

temperature (e.g., 600 K) and energies more than 50 eV beyond an edge. FEFF can

calculate this extended fine structure (EXELFS) but uses a path expansion method

rather than the full multiple scattering (FMS) procedure.

4.7.2 Band Structure Calculations

Most modern band structure methods are based on density functional theory (Kohn

and Sham, 1965). Among many DFT codes, two offer the ability to calculate ELNES

and are commercially available. CASTEP (http://www.castep.org/) is a pseudopo-

tential program developed at the University of Cambridge and now marketed by

4.7 Simulation of Energy-Loss Near-Edge Structure (ELNES) 289

Fig. 4.27 Experimental data (open circles) compared with Wien and FEFF calculations of the

nitrogen K-edge of hexagonal GaN, for two different principal directions of momentum transfer q.

The upper spectra relate to p

xy

transitions and the lower ones t o p

z

transitions. From Moreno et al.

(2007), copyright Elsevier. See also Moreno e t al. (2006) for Wien/FEFF comparison

Accelrys (http://accelrys.com/). Wien2k (http://www.wien2k.at/) was developed at

Vienna University of Technology from the original Wien program (Blaha et al.,

1990). It incorporates the TELNES program for calculating ELNES and the OPTIC

package, which can generate a low-loss dielectric function. A practical guide to

its use in EELS is given by Hébert (2007), and the description below is based on

that review. Seabourne et al. (2009) give further discussion of the choice of input

parameters for the Wien and CASTEP codes.

290 4 Quantitative Analysis of Energy-Loss Data

The first step in the Wien2k procedure is initialization, including choice of the

radius of the atomic sphere, within which initial-state wavefunctions are calculated.

Valence electrons are also taken to be atomic within this sphere and plane waves

outside. Incorrect choice leads to an unrealistic contribution of monopole terms

to the ELNES, so for low-lying (∼100 eV) edges a dipole approximation may be

necessary. The electron density is calculated and refined iteratively to generate a

self-consistent field (SCF) that satisfies the Schrödinger equation.

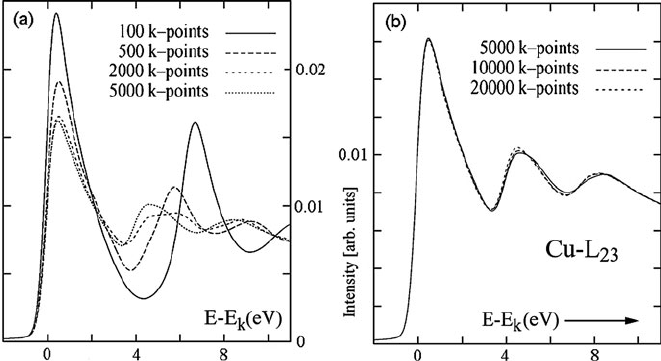

Next the DOS and ELNES are calculated, initially with a small number of

points within the Brillouin zone. Then the number of k-values is increased until

the result of the SCF calculation converges to a limit. Typically at least 5000

k-points are required; see Fig. 4.28. Besides calculating the DOS, the TELNES pro-

gram calculates the matrix element of Eq. (3.162) and integrates over momentum

transfer.

To compare with experimental data, the ELNES is broadened by a Gaussian func-

tion, whose width represents the instrumental energy resolution, and by a Lorentzian

to allow for core hole lifetime. An energy-dependent correction is also made for

final-state lifetime; see Section 3.8.1.

Correction for the effect of the core hole is done using the Z + 1 approximation or

else by removing one core electron in the model and adding it either to the number of

valence electrons or to the background charge, thereby preserving charge neutrality

within the unit cell. A supercell must be used, since the core hole occurs only once;

the number of atoms in this cell is increased until the ELNES converges. A 64-atom

supercell is usually sufficient. A partial core hole is possible; for the L

3

-edge in Cu,

a half-hole gave the best agreement with experiment.

Fig. 4.28 Wien2k calculations of the L

3

-edge of fcc copper, for different numbers of k-points in

the Brillouin zone. Lifetime broadening and instrumental broadening (0.7 eV) have been included.

From Hébert (2007), copyright Elsevier

4.7 Simulation of Energy-Loss Near-Edge Structure (ELNES) 291

Recent versions of TELNES can calculate for anisotropic materials as a func-

tion of specimen orientation and taking into account the convergence and collection

angles. To be accurate, this calculation must be fully relativistic (Appendix A).

The OPTIC package can calculate the low-loss dielectric function, for compar-

ison with that derived by Kramers–Kronig analysis of experimental EELS data.

Alternatively, WIEN2k can calculate the low-loss spectrum itself. This last approach

was used by Keast (2005), who calculated low-loss spectra of fourth, fifth, and some

sixth row elements of the periodic table and compared the results with experimental

data from the EELS atlas.

For accurate simulation of transition metal L-edges, multiplet effects

(Section 3.8.4) can be simulated by the CTM4XAS program (which can be accessed

by email to f.m.f.degroot@uu.nl). It is applicable to both XAS and EELS (Stavitski

and de Groot, 2010) but is intended to be used as an initial tool, prior to ab initio

multiplet calculations.

Chapter 5

TEM Applications of EELS

This final chapter is designed to show how the instrumentation, theory, and meth-

ods of EELS can be combined to extract useful information from TEM specimens,

with the possibility of high spatial resolution. As in previous chapters, we begin

with low-loss spectroscopy and energy filtering, followed by core-loss analysis and

elemental mapping, including factors that determine detection sensitivity and spa-

tial resolution. Structural information obtained through the analysis of spectral fine

structure is then discussed, and a final section shows how EELS has been applied

to a few selected materials systems. Meanwhile, Table 5.1 lists the information

obtainable by energy-loss spectroscopy and by alternative high-resolution methods.

5.1 Measurement of Specimen Thickness

It is often necessary to know the local thickness of a TEM specimen, to convert the

areal density provided by EELS or EDX analysis into elemental concentration, or to

estimate defect concentration from a TEM image, for example. Several techniques

Table 5.1 Analytical data obtainable by TEM and other methods

EELS measurement Information obtainable Alternative methods

Low-loss intensity Local thickness, mass thickness CBED, stereoscopy

Plasmon energy Valence-electron density

Plasmon peak shift Alloy composition CBED, EDXS

Low-loss fine structure Dielectric function, JDOS Optical spectroscopy

Low-loss fingerprinting Phase identification e

−

or x-ray diffraction

Core-loss intensities Elemental analysis EDXS, AES

Orientation dependence Atomic site location X-ray ALCHEMI

Near-edge fine structure Bonding information XAS (XANES)

Chemical shift of edges Oxidation state, valency XPS, XAS

L or M white-line ratio Valency, magnetic properties XPS, XAS

Extended fine structure Interatomic distances EXAFS, diffraction

Bethe ridge (ECOSS) Bonding information γ-ray Compton

293

R.F. Egerton, Electron Energy-Loss Spectroscopy in the Electron Microscope,

DOI 10.1007/978-1-4419-9583-4_5,

C

Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2011

294 5 TEM Applications of EELS

are available for in-situ thickness measurement. Analysis of a convergent-beam

diffraction pattern can achieve 5% accuracy (Castro-Fernandez et al., 1985)butis

time consuming and works only for crystalline specimens. Methods based on tilting

the specimen and observing the lateral shift of surface features (e.g., contamination

spots) are less accurate and may interfere with subsequent microscopy of the same

area. Measurement of the bremsstrahlung continuum in an x-ray emission spec-

trum (Hall, 1979) can give the mass thickness of organic specimens to an accuracy

of 20% but involves substantial electron dose and possible mass loss (Leapman

et al., 1984a, b). Measurement of the elastic scattering from an amorphous specimen

yields thickness in terms of an elastic mean free path or in terms of absolute mass

thickness if the chemical composition is known (Langmore et al., 1973; Langmore

and Smith, 1992; Pozsgai, 2007).

5.1.1 Log-Ratio Method

The most common procedure for estimating specimen thickness within a region

defined by the incident beam (or an area-selecting aperture) is to record a low-loss

spectrum and compare the area I

0

under the zero-loss peak with the total area I

t

under the whole spectrum. From Poisson statistics (Section 3.4), the thickness t is

given by

t/λ = ln(I

t

/I

0

) (5.1)

where λ is the total mean free path for all inelastic scattering. As discussed in

Section 3.4.1, λ in Eq. (5.1) should be interpreted as an effective mean free path

λ(β) if a collection aperture limits the scattering angles recorded by the spectrom-

eter to a value β, especially if this aperture cuts off an appreciable fraction of the

scattering (e.g. β < 20 mrad).

Before applying Eq. (5.1), any instrumental background should be subtracted

from the spectrum. Particularly for very thin specimens, correct estimation of this

background is essential for accurate thickness measurement. In the case of data

recorded from a CCD camera, the appropriate background will be a dark-current

spectrum acquired shortly before or after the energy-loss data, recorded with the

same integration time and number of readouts.

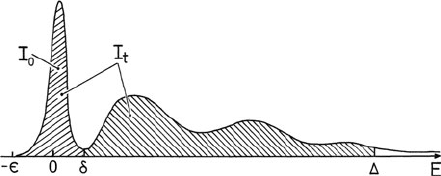

Measurement of I

t

and I

0

involves a choice of the energies ε, δ, and that define

the integration limits; see Fig. 5.1. The lower limit (–ε) of t he zero-loss region can

be taken anywhere to the left of the zero-loss peak where the intensity has fallen

practically to zero. The separation point δ for the zero-loss and inelastic regions

can be taken as the first minimum in intensity (Fig. 5.1) on the assumption that

errors arising from the overlapping tails of the zero-loss and inelastic components

approximately cancel. Alternatively, I

0

is measured by fitting the zero-loss peak to

an appropriate function, whose integral is known. The upper limit should corre-

spond to an energy loss above which further contribution to I

t

does not affect the

5.1 Measurement of Specimen Thickness 295

Fig. 5.1 The integrals and

energies involved in applying

the log-ratio method to

measure specimen t hickness

required accuracy. Although ≈ 100 eV is sufficient for a very thin light element

specimen, a larger value is needed for thicker or high-Z specimens, where inelastic

scattering extends to higher energy loss, due to contributions from plural scatter-

ing and inner shells, r espectively. The “compute thickness” procedure in the Gatan

EELS software reduces the need for recording a large energy range by extrapolating

the spectrum to higher energy loss.

The analysis of Section 3.4.3 indicates that Eq. (5.1) is relatively unaffected

by elastic scattering, even if a large fraction of the latter is intercepted by an

angle-limiting aperture. This situation arises because the elastic scattering is accom-

panied by a nearly equal fraction of mixed (elastic+inelastic) scattering. In practice,

Eq. (5.1) has been judged to be valid (within about 10%) for t/λ as large as 4

(Hosoi et al., 1981; Leapman et al., 1984a; Lee et al., 2002). In the case of very

thin specimens (t/λ < 0.1), s urface excitations are significant and might cause an

overestimate of thickness (Batson, 1993a).

For t/λ > 5, an alternative procedure is available for thickness measurement,

based on the peak energy and width of the multiple scattering distribution (Perez

et al., 1977; Whitlock and Sprague, 1982); see Section 3.4.4.

5.1.1.1 Measurement of Absolute Thickness

Equation (5.1) provides a thickness in terms of the inelastic MFP, which can be

useful for measuring the relative thicknesses of similar specimens or thickness vari-

ations within a specimen of uniform composition. To obtain absolute thickness,

a value for λ is required. A rough estimate (in nm) is given by λ ≈ (0.8)E

0

,

where E

0

is the incident electron energy in keV. For 100-keV electrons and λ >

5 mrad, this estimate is valid within a factor of 2 for typical materials except ice; see

Table 5.2.

For materials of known composition, the inelastic mean free path can be calcu-

lated. However, atomic models such as that of Lenz (1954) yield cross sections that

may be too high, so that λ is underestimated; the free-electron plasmon formula,

Eq. (3.58), gives mean free paths that are appropriate for some materials but are

generally an overestimate.

Realistic values of mean free path are possible by using scattering theory to

parameterize λ in terms of the collection semi-angle β, the incident energy E

0

, and

a parameter that depends on the chemical composition of the specimen. Assuming

296 5 TEM Applications of EELS

Table 5.2 Values of E

m

obtained from energy-loss measurements, together with inelastic mean

free paths for 100-keV electrons

100-keV MFP (nm)

Material Type of specimen Reference E

m

(eV) λ (10 mrad) λ (100 mrad)

Al Single-crystal foil M&88 17.2 100 100

Al Polycrystalline film C90, YE94 16.8 101 101

Al

2

O

3

Polycrystalline film E92 15.9 106 106

Ag Polycrystalline film EC87, C90 26.3 71 71

Au Polycrystalline film EC87, C90 35.9 56 56

Be Single-crystal foil M&88 12.4 129 129

BN Crystalline flake E81c 17.2 99 99

C Arc-evaporated film C90, E92 14.2 116 116

CC

60

thin film E92 14.4 115 115

C Diamond crystal E92 19.1 88 88

Cr Polycrystalline film E92 25.1 74 74

Cu Polycrystalline film C90 30.8 63 63

Fe Polycrystalline film EC87, C90 25.0 74 57

(Fe) 306 stainless steel M&88 23.3 78 61

GaAs Single crystal E92 18.2 95 74

Hf Single-crystal foil M&88 35.3 57 41

H

2

O Crystalline ice S&93, E92 6.7 220 200

NiO Single crystal M&88 19.8 89 71

Si Single crystal EC87 15.0 111 91

SiO

2

Amorphous film E92 13.8 119 99

Zr Single-crystal foil M&88 24.5 75 57

C90 = Crozier (1990); E81c = Egerton (1981c); E92 = Egerton (1992a); EC87 = Egerton and

Cheng (1987); M&88 = Malis et al. (1988); S&93 =Sun et al. (1993); YE94 =Yang and Egerton

(1995). The last two columns give mean free paths for 100-keV incident electrons: λ(10 mrad) for

β = 10 mrad and λ(100 mrad) for β ≈ 100 mrad, obtained from λ(10 mrad) by making use of the

angular distribution predicted by Eq. (3.16)

β<<(E/E

0

)

1/2

, implying β <15mradatE

0

= 100 keV, Malis et al. (1988)

parameterized the inelastic mean free path on the basis of a dipole formula:

λ ≈

106F(E

0

/E

m

)

ln(2βE

0

/E

m

)

(5.2)

In Eq. (5.2), λ is in nm, β in mrad, E

0

in keV, and E

m

in eV; F is a relativistic factor

(0.768 for E

0

= 100 keV, 0.618 for E

0

= 200 keV) defined by

F =

T

E

0

=

m

0

v

2

2E

0

=

1 +E

0

/1022 keV

(1 +E

0

/511 keV)

2

(5.2a)

Equation (5.2) is based on Eq. (3.58), with an appropriate value of F but with a

nonrelativistic expression for θ

E

within the logarithm term.

By recording the low-loss spectrum from a specimen of known thickness, with

known β and E

0

, λ can be determined from Eq. (5.1) and converted to E

m

by itera-

tive use of Eq. (5.2). Materials for which this has been done are listed in Table 5.2;

5.1 Measurement of Specimen Thickness 297

the appropriate values of E

m

can then be used in Eq. (5.2) to calculate the mean free

path appropriate to a particular collection angle, as in the PMFP program (Appendix

B).

For an element not listed in Table 5.2 but whose atomic number Z is known,

Malis et al. (1988) proposed a formula based on measurements of 11 materials at

incident energies of 80 and 100 keV:

E

m

≈ 7.6 Z

0.36

(5.3)

This formula is roughly consistent with the Lenz atomic model of inelastic scat-

tering, Eq. (3.16), but makes no allowance for differences in crystal structure or

electron density; it would predict the same mean free path for graphite, diamond,

and amorphous carbon, for example. In the case of a compound, the Lenz model

suggests an effective atomic number for use in Eq. (5.3):

Z

eff

≈

$

i

f

i

Z

1.3

i

$

i

f

i

Z

0.3

i

(5.4)

where f

i

is the atomic fraction of each element of atomic number Z

i

.

For large collection apertures (β >20mradforE

0

= 100 keV, >10 mrad at

200 keV), Eq. (5.2) is not applicable. This total inelastic mean free path, appro-

priate to low-loss spectra recorded without an angle-limiting aperture, is given to a

reasonable approximation by substituting β = 25 mrad (15 mrad at 200 keV) in Eq.

(5.2). Estimates of total inelastic mean free path for 100-keV electrons are given in

the last column of Table 5.2; 200-keV measurements are tabulated in Appendix C.

More recently, Iakoubovskii et al. (2008a, b) used a 200-kV STEM probe

(α = 20 mrad, β = 5 mrad) to measure t/λ in specimens of 36 elements and 34

binary oxides. Local thickness was determined mainly from the Kramers–Kronig

sum rule (Section 5.1.2). The resulting values for λ are tabulated in Iakoubovskii

et al. (2008b). They are generally larger than given by Eq. (5.2) and were found

to be more accurately modeled as a function of specimen density ρ rather than

atomic number; see Fig. 5.2a, b. As a result, Iakoubovskii et al. (2008a) proposed

the following formula:

λ =

200FE

0

11ρ

0.3

ln

α

2

+β

2

+2θ

2

E

+δ

2

α

2

+β

2

+2θ

2

c

+δ

2

×

θ

2

c

θ

2

E

(5.5)

where the incident convergence semi-angle α and the collection semi-angle β are

in mrad, δ

2

=

α

2

−β

2

, θ

c

= 20 mrad, ρ is the specific gravity of the specimen

(density in g/cm

3

). The characteristic angle θ

E

was defined as

θ

E

= 5.5ρ

0.3

/(FE

0

) (5.5a)

where the relativistic factor F is given by Eq. (5.2a). Equation (5.5a) incorporates

an approximation to the incident convergence correction that does not assume that α