Egerton R.F. Electron Energy-Loss Spectroscopy in the Electron Microscope

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

x Contents

4.3.3 Bayesian Deconvolution ................. 255

4.3.4 Other Methods ...................... 256

4.4 Separation of Spectral Components . . ............. 257

4.4.1 Least-Squares Fitting . .................. 258

4.4.2 Two-Area Fitting . . . .................. 260

4.4.3 Background-Fitting Errors . . . ............. 261

4.4.4 Multiple Least-Squares Fitting . ............. 265

4.4.5 MultivariateStatisticalAnalysis............. 265

4.4.6 Energy- and Spatial-Difference Techniques . . . .... 269

4.5 ElementalQuantification..................... 270

4.5.1 IntegrationMethod.................... 270

4.5.2 CalculationofPartialCrossSections .......... 273

4.5.3 Correction for Incident Beam Convergence . . . .... 274

4.5.4 Quantification from MLS Fitting ............ 276

4.6 Analysis of Extended Energy-Loss Fine Structure . . . .... 277

4.6.1 FourierTransformMethod................ 277

4.6.2 Curve-Fitting Procedure ................. 284

4.7 Simulation of Energy-Loss Near-Edge Structure (ELNES) . . . 286

4.7.1 Multiple Scattering Calculations ............. 286

4.7.2 BandStructureCalculations............... 288

5 TEM Applications of EELS ...................... 293

5.1 Measurement of Specimen Thickness . ............. 293

5.1.1 Log-RatioMethod.................... 294

5.1.2 Absolute Thickness from the K–K Sum Rule . . .... 302

5.1.3 Mass Thickness from the Bethe Sum Rule . . . .... 304

5.2 Low-Loss Spectroscopy . . . .................. 306

5.2.1 IdentificationfromLow-LossFineStructure ...... 306

5.2.2 Measurement of Plasmon Energy

and Alloy Composition ................. 309

5.2.3 CharacterizationofSmallParticles ........... 310

5.3 Energy-Filtered Images and Diffraction Patterns ........ 314

5.3.1 Zero-Loss Images . . .................. 315

5.3.2 Zero-LossDiffractionPatterns.............. 317

5.3.3 Low-Loss Images . . .................. 318

5.3.4 Z-Ratio Images ...................... 319

5.3.5 ContrastTuningandMPLImaging ........... 320

5.3.6 Core-Loss Images and Elemental Mapping . . . .... 321

5.4 Elemental Analysis from Core-Loss Spectroscopy . . . .... 324

5.4.1 Measurement of Hydrogen and Helium . ........ 327

5.4.2 Measurement of Lithium, Beryllium, and Boron .... 329

5.4.3 Measurement of Carbon, Nitrogen, and Oxygen .... 330

5.4.4 MeasurementofFluorineandHeavierElements .... 333

5.5 SpatialResolutionandDetectionLimits............. 335

5.5.1 Electron-OpticalConsiderations............. 335

Contents xi

5.5.2 LossofResolutionDuetoElasticScattering ...... 336

5.5.3 DelocalizationofInelasticScattering .......... 337

5.5.4 StatisticalLimitationsandRadiationDamage...... 340

5.6 Structural Information from EELS . . . ............. 346

5.6.1 Orientation Dependence of Ionization Edges . . .... 346

5.6.2 Core-LossDiffractionPatterns.............. 350

5.6.3 ELNES Fingerprinting .................. 352

5.6.4 Valency and Magnetic Measurements

fromWhite-LineRatios ................. 357

5.6.5 UseofChemicalShifts.................. 361

5.6.6 Use of Extended Fine Structure ............. 362

5.6.7 Electron–Compton (ECOSS) Measurements . . .... 366

5.7 Application to Specific Materials . . . ............. 368

5.7.1 Semiconductors and Electronic Devices . ........ 368

5.7.2 Ceramics and High-Temperature Superconductors . . . 374

5.7.3 Carbon-Based Materials ................. 378

5.7.4 Polymers and Biological Specimens . . . ........ 386

5.7.5 Radiation Damage and Hole Drilling . . ........ 389

Appendix A Bethe Theory for High Incident Energies

and Anisotropic Materials ................. 399

A.1 Anisotropic Specimens . . . ............. 402

Appendix B Computer Programs ..................... 405

B.1 First-Order Spectrometer Focusing . . ........ 405

B.2 Cross Sections for Atomic Displacement

andHigh-AngleElasticScattering .......... 406

B.3 Lenz-Model Elastic and Inelastic Cross Sections . . . 406

B.4 SimulationofaPlural-ScatteringDistribution .... 407

B.5 Fourier-Log Deconvolution . ............. 408

B.6 Maximum-Likelihood Deconvolution ........ 409

B.7 Drude Simulation of a Low-Loss Spectrum . .... 409

B.8 Kramers–KronigAnalysis .............. 410

B.9 Kröger Simulation of a Low-Loss Spectrum . .... 412

B.10 Core-LossSimulation................. 412

B.11 Fourier Ratio Deconvolution ............. 413

B.12 Incident-Convergence Correction . . . ........ 414

B.13 Hydrogenic K-Shell Cross Sections . ........ 414

B.14 Modified-Hydrogenic L-Shell Cross Sections .... 415

B.15 Parameterized K-, L-, M-, N-, and O-Shell

CrossSections..................... 416

B.16 Measurement of Absolute Specimen Thickness . . . 416

B.17 TotalInelasticandPlasmonMeanFreePaths .... 417

B.18 Constrained Power-Law Background Fitting . .... 417

Appendix C Plasmon Energies and Inelastic Mean Free Paths ..... 419

xii Contents

Appendix D Inner-Shell Energies and Edge Shapes ........... 423

Appendix E Electron Wavelengths, Relativistic Factors,

and Physical Constants ................... 427

Appendix F Options for Energy-Loss Data Acquisition ........ 429

References .................................. 433

Index ..................................... 485

Chapter 1

An Introduction to EELS

Electron energy-loss spectroscopy (EELS) involves analyzing the energy distribu-

tion of initially monoenergetic electrons after they have interacted with a specimen.

This interaction is sometimes confined to a few atomic layers, as when a beam of

low-energy (100–1000 eV) electrons is “reflected” from a solid surface. Because

high voltages are not involved, the apparatus is relatively compact but the low

penetration depth implies the use of ultrahigh vacuum. Otherwise information is

obtained mainly from the carbonaceous or oxide layers on the specimen’s surface.

At these low primary energies, a monochromator can reduce the energy spread of

the primary beam to a few millielectron volts (Ibach, 1991) and if the spectrometer

has comparable resolution, the spectrum contains features characteristic of energy

exchange with the vibrational modes of surface atoms, as well as valence electron

excitation in these atoms. The technique is therefore referred to as high-resolution

electron energy-loss spectroscopy (HREELS) and is used to study the physics and

chemistry of surfaces and of adsorbed atoms or molecules. Although it is an impor-

tant tool of surface science, HREELS uses concepts that are somewhat different to

those i nvolved in electron microscope studies and will not be discussed further in

the present volume. The instrumentation, theory, and applications of HREELS are

described by Ibach and Mills (1982) and by Kesmodel (2006).

Surface sensitivity is also achieved at higher electron energies if the electrons

arrive at a glancing angle to the surface, so that they penetrate only a shallow

depth before being scattered out. Reflection energy-loss spectroscopy (REELS) has

been carried out with 30-keV electrons in a molecular beam epitaxy (MBE) cham-

ber, allowing elemental and structural analysis of the surface during crystal growth

(Atwater et al., 1993). Glancing angle REELS is also possible in a transmission

electron microscope (TEM) at a primary energy of 100 keV or more, as discussed

in Section 3.3.5.

If the electrons arrive perpendicular to a sufficiently thin specimen and their

kinetic energy is high enough, practically all of them are transmitted without reflec-

tion or absorption. Interaction then takes place inside the specimen, and information

about its internal structure can be obtained by passing the transmitted beam into a

spectrometer. For 100-keV incident energy, the specimen must be less than 1 μm

thick and preferably below 100 nm.

1

R.F. Egerton, Electron Energy-Loss Spectroscopy in the Electron Microscope,

DOI 10.1007/978-1-4419-9583-4_1,

C

Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2011

2 1 An Introduction to EELS

Such specimens are s elf-supporting only over limited areas, so the incident elec-

trons must be focused into a small diameter, but in doing so we gain the advantage

of analyzing small volumes. Electron lenses that can focus the electrons and guide

them into an electron spectrometer are already present in a transmission electron

microscope, so transmission EELS is usually carried out using a TEM, taking

advantage of its imaging and diffraction capabilities to identify the structure of the

material being analyzed.

In this introductory chapter, we present a simplified account of the physical pro-

cesses that occur while “fast” electrons are passing through a specimen, followed

by an overview of energy-loss spectra and the instruments that have been developed

to record such spectra. To identify the strengths and limitations of EELS, we con-

clude by considering the alternative techniques that are available for analyzing the

chemical and physical properties of a solid specimen.

1.1 Interaction of Fast Electrons with a Solid

When electrons enter a solid, they interact with the constituent atoms through elec-

trostatic (Coulomb) forces. As a result of these forces, some of the electrons are

scattered: the direction of their momentum is changed and in many cases they trans-

fer an appreciable amount of energy to the specimen. It is convenient to divide the

scattering into two broad categories: elastic and inelastic.

Elastic scattering involves Coulomb interaction with atomic nuclei. Each nucleus

represents a high concentration of charge; the electric field in its immediate vicinity

is intense and an incident electron that approaches close enough is deflected through

a large angle. Such high-angle deflection is referred to as Rutherford scattering,

since its angular distribution is the same as that calculated by Rutherford for the

scattering of alpha particles. If the deflection angle exceeds 90

◦

, the electron is said

to be backscattered and may emerge from the specimen at the same surface that it

entered (Fig. 1.1a).

The majority of electrons travel further from the center of an atom, where the

electrostatic field of the nucleus is weaker because of the inverse square law and

the fact that the nucleus is partially shielded (screened) by atomic electrons. Most

incident electrons are therefore scattered through small angles, typically a few

degrees (10–100 mrad) in the case of 100-keV incident energy. In a gas or (to a

first approximation) an amorphous solid, each atom or molecule scatters electrons

independently. In a crystalline solid, the wave nature of the incident electrons cannot

be ignored and interference between scattered electron waves changes the contin-

uous distribution of scattered intensity into one that is sharply peaked at angles

characteristic of the atomic spacing. The elastic scattering is then referred to as

diffraction.

Although the term elastic usually implies negligible exchange of energy, this

condition holds only when the scattering angle is small. For a head-on colli-

sion (scattering angle = 180

◦

), the energy transfer is given (in electron volt) by

E

max

= 2148 (E

0

+ 1.002)E

0

/A, where E

0

is the incident energy in megaelectron

1.1 Interaction of Fast Electrons with a Solid 3

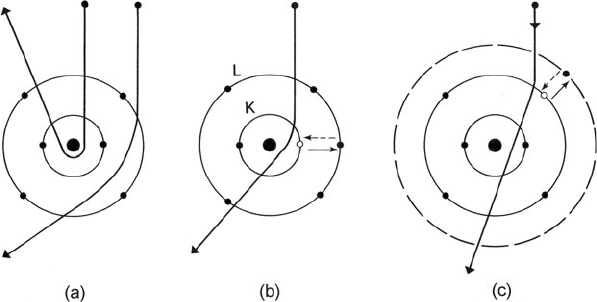

Fig. 1.1 A classical (particle) view of electron scattering by a single atom (carbon). (a) Elastic

scattering is caused by Coulomb attraction by the nucleus. Inelastic scattering results from

Coulomb repulsion by ( b)inner-,or(c) outer-shell electrons, which are excited to a higher energy

state. The reverse transitions (de-excitation) are shown by broken arrows

volt and A is the atomic weight of the target nucleus. For E

0

=100 keV, E

max

> 1eV

and, in the case of a light element, may exceed the energy needed to displace the

atom from its lattice site, resulting in displacement damage within a crystalline sam-

ple, or removal of atoms by sputtering from its surface. However, such high-angle

collisions are rare; for the majority of elastic interactions, the energy transfer is

limited to a small fraction of an electron volt, and in crystalline materials is best

described in terms of phonon excitation (vibration of the whole array of atoms).

Inelastic scattering occurs as a result of Coulomb interaction between a fast inci-

dent electron and the atomic electrons that surround each nucleus. Some inelastic

processes can be understood in terms of t he excitation of a single atomic electron

into a Bohr orbit (orbital) of higher quantum number (Fig. 1.1b) or, in terms of

energy band theory, to a higher energy level (Fig. 1.2).

Consider first the interaction of a fast electron with an inner-shell electron, whose

ground-state energy lies typically some hundreds or thousands of electron volts

below the Fermi level of the solid. Unoccupied electron states exist only above

the Fermi level, so the inner-shell electron can make an upward transition only

if it absorbs an amount of energy similar to or greater than its original binding

energy. Because the total energy is conserved at each collision, the fast electron

loses an equal amount of energy and is scattered through an angle typically of

the order of 10 mrad for 100-keV incident energy. As a result of this inner-shell

scattering, the target atom is left in a highly excited (or ionized) state and will

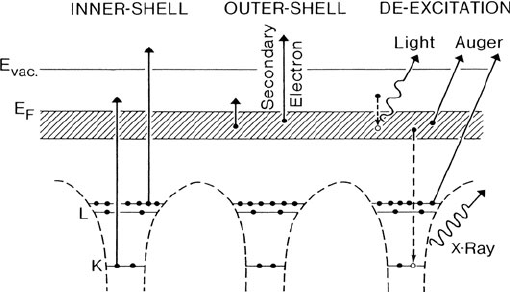

quickly lose its excess energy. In the de-excitation process, an outer-shell elec-

tron (or an inner-shell electron of lower binding energy) undergoes a downward

transition to the vacant “core hole” and the excess energy is liberated as electro-

magnetic radiation (x-rays) or as kinetic energy of another atomic electron (Auger

emission).

4 1 An Introduction to EELS

Fig. 1.2 Energy-level diagram of a solid, including K-andL-shell core levels and a valence band

of delocalized states (shaded); E

F

is the Fermi level and E

vac

the vacuum level. The primary pro-

cesses of inner- and outer-shell excitation are shown on the left, secondary processes of photon and

electron emission on the right

Outer-shell electrons can also undergo single-electron excitation. In an insula-

tor or semiconductor, a valence electron makes an interband transition across the

energy gap; in the case of a metal, a conduction electron makes a transition to a

higher state, possibly within the same energy band. If the final state of these transi-

tions lies above the vacuum level of the solid and if the excited atomic electron has

enough energy to reach the surface, it may be emitted as a secondary electron.As

before, the fast electron supplies the necessary energy (generally a few electron volts

or tens of electron volts) and is scattered through an angle of typically 1 or 2 mrad

(for E

0

≈ 100 keV). In the de-excitation process, electromagnetic radiation may be

emitted in the visible region (cathodoluminescence), although in many materials the

reverse transitions are radiationless and the energy originally deposited by the fast

electron appears as heat. Particularly in the case of organic compounds, not all of

the valence electrons return to their original configuration; the permanent disruption

of chemical bonds is described as ionization damage or radiolysis.

As an alternative to the single-electron mode of excitation, outer-shell inelastic

scattering may involve many atoms of the solid. This collective effect is known as

a plasma resonance (an oscillation of the valence electron density) and takes the

form of a longitudinal traveling wave, similar in some respects to a sound wave.

According to quantum theory, the excitation can also be described in terms of the

creation of a pseudoparticle, the plasmon, whose energy is E

p

= ω

p

, where is

Planck’s constant and ω

p

is the plasmon frequency in radians per second, which is

proportional to the square root of the valence electron density. For the majority of

solids, E

p

lies in the range 5–30 eV.

Plasmon excitation being a collective phenomenon, the excess energy is shared

among many atoms when viewed over an extended time period. At a given instant,

however, the energy is likely to be carried by only one electron (Ferrell, 1957),

1.2 The Electron Energy-Loss Spectrum 5

which makes plausible the fact that plasmons can be excited in insulators, E

p

being

generally higher than the excitation energy of the valence electrons (i.e., the band

gap). The essential requirement for plasmon excitation is that the participating elec-

trons can communicate with each other and share their energy, a condition that is

fulfilled for a band of delocalized states but not for the atomic-like core levels. The

lifetime of a plasmon i s very short; it decays by depositing its energy (via interband

transitions) i n the form of heat or by creating secondary electrons.

In addition to exciting volume or “bulk” plasmons within the specimen, a fast

electron can create surface plasmons at each exterior surface. However, these surface

excitations dominate only in very thin (<20 nm) samples or small particles.

Plasmon excitation and single-electron excitation represent alternative modes of

inelastic scattering. In materials in which the valence electrons behave somewhat

like free particles (e.g., the alkali metals), the collective form of response is predom-

inant. In other cases (e.g., rare gas solids), plasmon effects are weak or nonexistent.

Most materials fall between these two extremes.

1.2 The Electron Energy-Loss Spectrum

The secondary processes of electron and photon emission from a specimen can be

studied in detail by appropriate spectroscopies, as discussed in Section 1.4. In elec-

tron energy-loss spectroscopy, we deal directly with the primary process of electron

excitation, which results in the fast electron losing a characteristic amount of energy.

The transmitted electron beam is directed into a high-resolution electron spectrom-

eter that separates the electrons according to their kinetic energy and produces an

electron energy-loss spectrum showing the number of electrons (scattered intensity)

as a function of their decrease in kinetic energy.

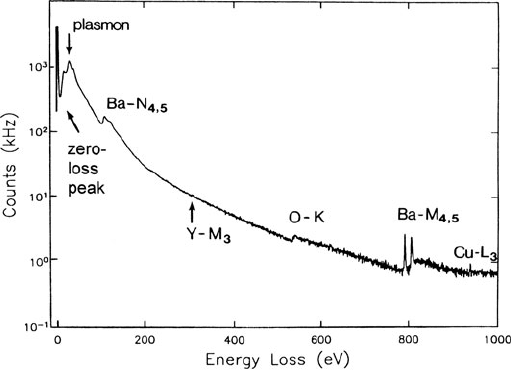

A typical loss spectrum, recorded from a thin specimen over a range of about

1000 eV, is shown in Fig. 1.3. The first zero-loss or “elastic” peak represents

electrons that are transmitted without suffering measurable energy loss, including

electrons scattered elastically and those that excite phonon modes, for which the

energy loss is less than the experimental energy resolution. In addition, the zero-

loss peak includes electrons that can be regarded as unscattered, since they lose no

energy and remain undeflected after passing through the specimen. The correspond-

ing electron waves undergo a phase change but this is detectable only by holography

or high-resolution imaging.

Inelastic scattering from outer-shell electrons is visible as a peak (or a series of

peaks, in thicker specimens) in the 4–40 eV region of the spectrum. At higher energy

loss, the electron intensity decreases rapidly, making it convenient to use a logarith-

mic scale for the recorded intensity, as in Fig. 1.3. Superimposed on this smoothly

decreasing intensity are features that represent inner-shell excitation; they take the

form of edges rather than peaks, the inner-shell intensity rising rapidly and then

falling more slowly with increasing energy loss. The sharp rise occurs at the ioniza-

tion threshold, whose energy-loss coordinate is approximately the binding energy

of the corresponding atomic shell. Since inner-shell binding energies depend on the

6 1 An Introduction to EELS

Fig. 1.3 Electron energy-loss spectrum of a high-temperature superconductor (YBa

2

Cu

3

O

7

) with

the electron intensity on a logarithmic scale, showing zero-loss and plasmon peaks and ionization

edges arising from each element. Courtesy of D.H. Shin, Cornell University

atomic number of the scattering atom, the ionization edges present in an energy-loss

spectrum reveal which elements are present within the specimen. Quantitative ele-

mental analysis is possible by measuring an area under the appropriate ionization

edge, making allowance for the underlying background.

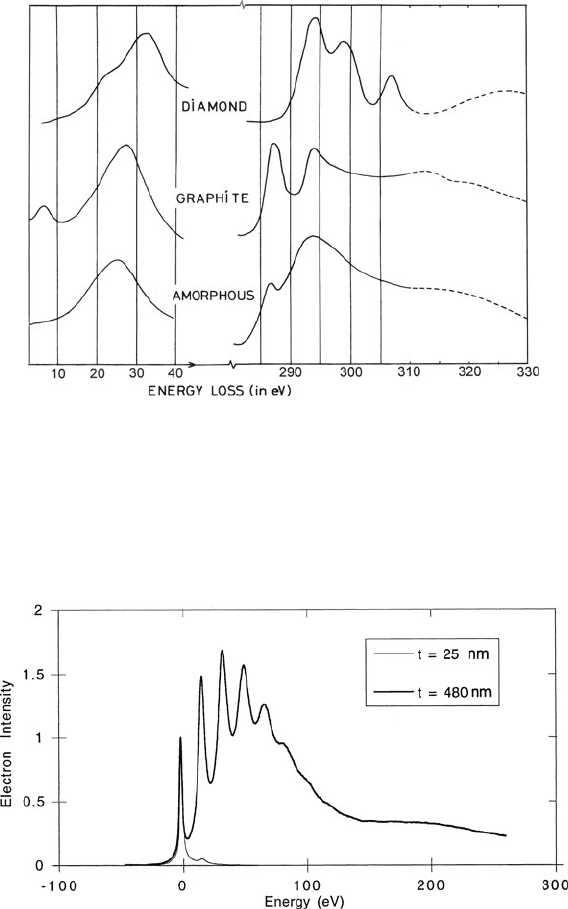

When viewed in greater detail, both the valence electron (low-loss) peaks and the

ionization edges possess a fine structure that reflects the crystallographic or energy

band structure of the specimen. Even with an energy resolution of 2 eV, it is possible

to distinguish between different forms of an element such as carbon, as illustrated

in Fig. 1.4.

If the energy-loss spectrum is recorded from a sufficiently thin region of the spec-

imen, each spectral feature corresponds to a different excitation process. In thicker

samples, there is a substantial probability that a transmitted electron will be inelas-

tically scattered more than once, giving a total energy loss equal to the sum of the

individual losses. In the case of plasmon scattering, the result is a series of peaks at

multiples of the plasmon energy (Fig. 1.5). The plural (or multiple) scattering peaks

have appreciable intensity if the specimen thickness approaches or exceeds the mean

free path of the inelastic scattering process, which is typically 50–150 nm for outer-

shell scattering at 100-keV incident energy. Electron microscope specimens are

typically of this thickness, so plural scattering is usually significant and generally

unwanted, since it distorts the shape of the energy-loss spectrum. Fortunately it be

removed by various deconvolution procedures.

On a classical (particle) model of scattering, the mean free path (MFP) is an

average distance between scattering events. More generally, the MFP is inversely

proportional to a scattering cross section, which is a direct (rather than inverse)

1.2 The Electron Energy-Loss Spectrum 7

Fig. 1.4 Low-loss and K-ionization regions of the energy-loss spectra of three allotropes of car-

bon, recorded on photographic plates and then digitized (Egerton and Whelan, 1974a, b). The

plasmon peaks occur at different energies (33 eV in diamond, 27 eV in graphite, and 25 eV in

amorphous carbon) because of the different valence electron densities. The K-edge threshold is

shifted upward by about 5 eV in diamond due to the formation of an energy gap. The broad peaks

indicated by dashed lines are caused by electrons that undergo both K-shell and plasmon scattering

Fig. 1.5 Energy-loss spectra recorded from silicon specimens of two different thicknesses. The

thin sample gives a strong zero-loss peak and a weak first-plasmon peak; the thicker sample

provides plural scattering peaks at multiples of the plasmon energy