Egerton R.F. Electron Energy-Loss Spectroscopy in the Electron Microscope

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

198 3 Physics of Electron Scattering

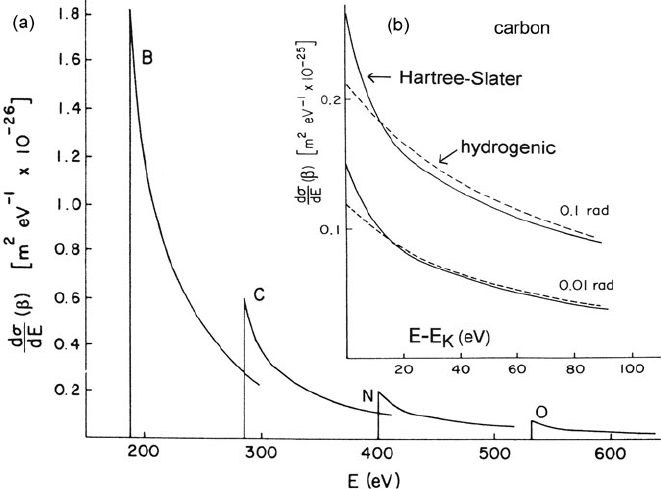

Fig. 3.42 (a) Energy-differential cross section for K-shell ionization in boron, carbon, nitrogen,

and oxygen, calculated for 80-keV incident electrons and 3-mrad collection semi-angle using the

Hartree–Slater method. (b) Comparison of Hartree–Slater and hydrogenic calculations for the car-

bon K-edge, taking E

0

= 80 keV and collection semi-angles of 10 and 100 mrad (Leapman et al.,

1980)

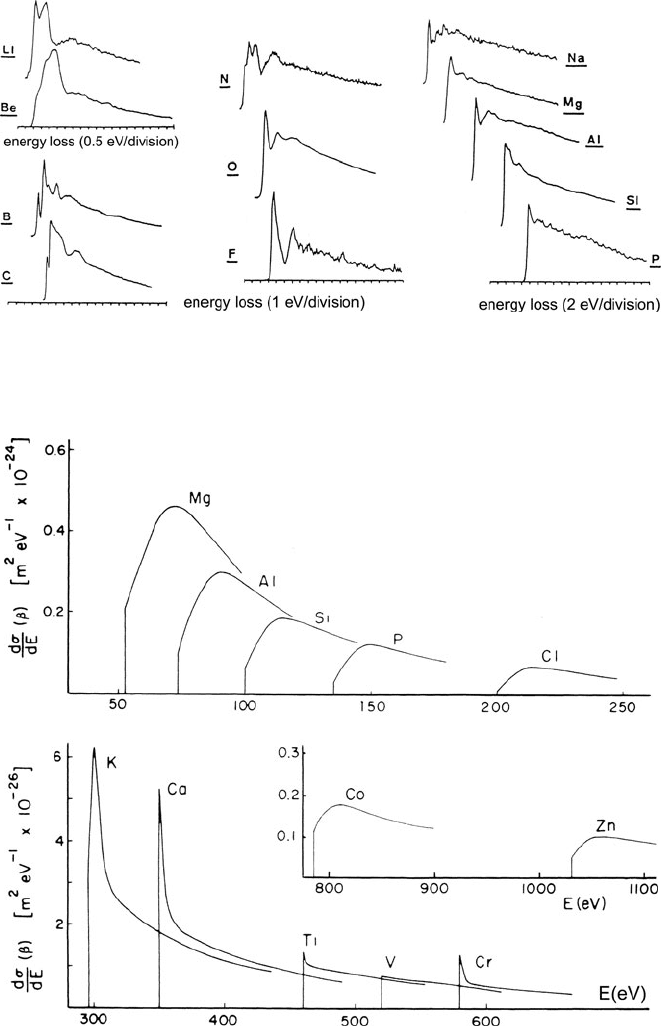

As seen in Fig. 3.43, measured K-shell edges conform to this same overall shape

but with the addition of some pronounced fine structure. The K-ionization edges

remain basically sawtooth shaped for third-period elements (Na to Cl). Their inten-

sities are lower, resulting in a relatively high noise content in the experimental

data.

Calculations of L

23

edges (excitation of 2p electrons) in third-period elements

(Na to Cl) show that they have a more rounded profile, as in Fig. 3.44. The intensity

exhibits a delayed maximum of 10–20 eV above the ionization threshold, resulting

from the l

’

(l + 1) t erm in the radial Schrödinger equation, Eq. (3.128), which causes

a maximum to appear in the effective atomic potential. At energies just above the

ionization threshold, this “centrifugal barrier” prevents overlap between the initial

(2p) and final-state wavefunctions, particularly for final states with a large angular

momentum quantum number l

. Measured L

23

edges display this delayed maximum

(Ahn, 2004), although excitonic effects can sharpen the edge, particularly in the case

of insulating materials (see page 212).

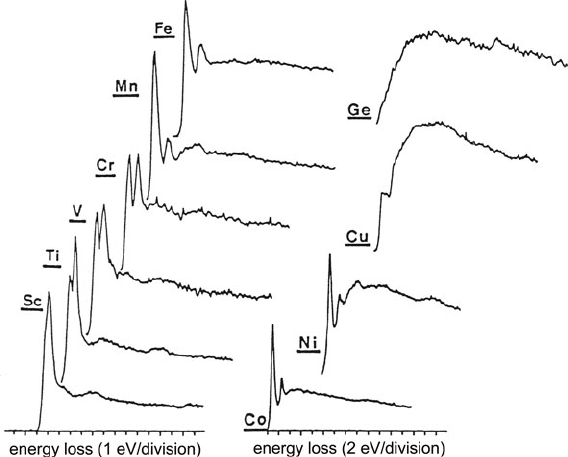

Fourth-period elements give rise to quite distinctive L-edges. Atomic calcula-

tions predict that the L

23

edges of K, Ca, and Sc will be sharply peaked at the

3.7 The Form of Inner-Shell Edges 199

Fig. 3.43 K-ionization edges (after background subtraction) measured by EELS with 120-keV

incident electrons and collection semi-angles in the range of 3–15 mrad. The background intensity

before each edge has been extrapolated and subtracted, as described in Chapter 4. From Zaluzec

(1982), copyright Elsevier

Fig. 3.44 Hartree–Slater calculations of L

23

edges, for 80-keV incident electrons and a collection

semi-angle of 10 mrad (Leapman et al., 1980)

200 3 Physics of Electron Scattering

ionization threshold because of a “resonance” effect: the dipole selection rule favors

transitions to final states with d-character (l

= 2) and the continuum 3d wavefunc-

tion is sufficiently compact to fit mostly within the centrifugal barrier, resulting in

strong overlap with the core-level (2p) wavefunction and a large oscillator strength

at threshold (Leapman et al., 1980). These sharp threshold peaks are known as

white lines since they were first observed in x-ray absorption spectra where the

high absorption peak at the ionization threshold resulted in almost no blackening

on a photographic plate. The white lines are mainly absent in the calculated L

23

-

edge profiles of transition metal atoms (Fig. 3.44) because the calculations neglect

excitation to bound states (discrete unoccupied 3d levels). In a solid, however, these

atomic levels form a narrow energy band with a high density of vacant d-states,

leading to the strong threshold peaks observed experimentally; see Fig. 3.45.

Spin–orbit splitting causes the magnitude of the L

2

binding energy to be slightly

higher than that of the L

3

level. Consequently, two threshold peaks are observed,

whose separation increases with increasing atomic number (Fig. 3.45). The ratio

of intensities of the L

3

and L

2

white lines is found to deviate from the “statisti-

cal” value (2.0) based on the relative occupancy of the initial-state levels (Leapman

et al., 1982). This deviation is caused by spin coupling between the core hole and

the final state (Barth et al., 1983) and is useful for determining valence state; see

Section 5.6.4.

Fig. 3.45 L-edges of fourth-period elements measured using 120-keV electrons and a collection

semi-angle of 5.7 mrad. From Zaluzec (1982), copyright Elsevier

3.7 The Form of Inner-Shell Edges 201

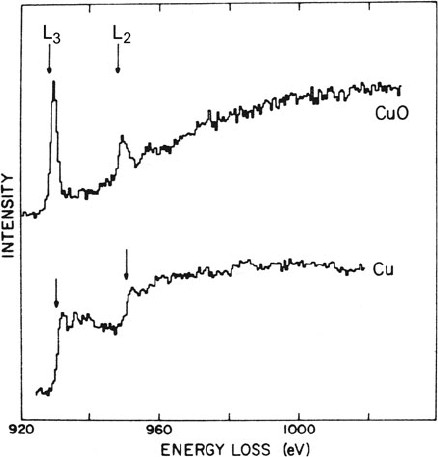

Fig. 3.46 Cu L

23

edges in

metallic copper and in cupric

oxide, measured using

75-keV electrons scattered up

to β =2 mrad. From

Leapman et al. (1982),

copyright American Physical

Society. Available at http://

link.aps.org/abstract/PRB/

v26/p614

In the case of metallic copper, the d-band is full and threshold peaks are absent,

but in compounds such as CuO electrons are drawn away from the copper atom,

leading to empty d-levels and sharp L

2

and L

3

threshold peaks; see Fig. 3.46. Fourth-

period elements of higher atomic number (Zn to Br) have full d-shells and the L

23

edges display delayed maxima, as in the case of Ge (Fig. 3.45).

Hartree–Slater calculations of L

1

edges indicate that they have a sawtooth shape

(like K-edges) but relatively low intensity. They are usually observable as a small

step on the falling background of the preceding L

23

edge; see Fig. 3.45.

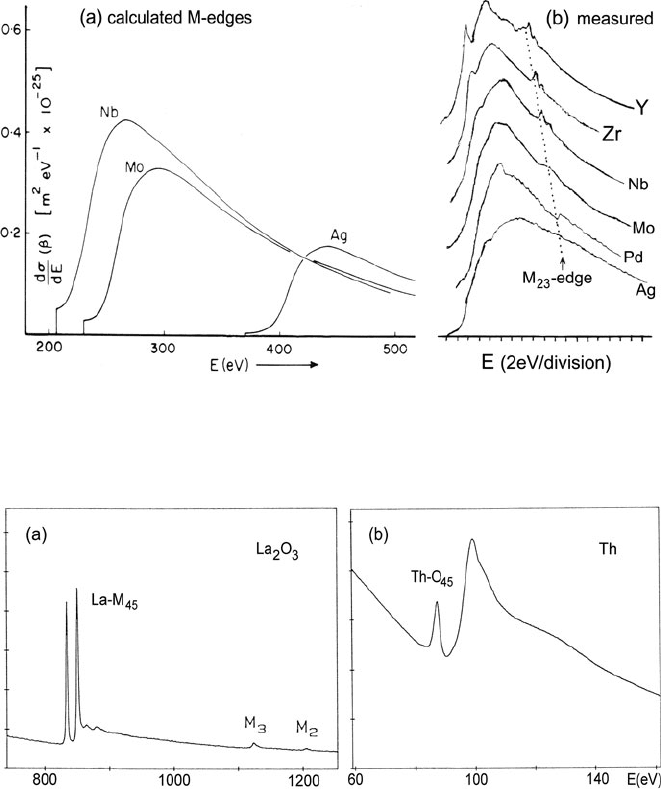

M

45

edges are prominent for fifth-period elements and appear with the intensity

maximum delayed by 50–100 eV beyond the threshold (Fig. 3.47) because the cen-

trifugal potential suppresses the optically preferred 3d → 4f transitions just above

the threshold (Manson and Cooper, 1968). Within the s ixth period, between Cs

(Z = 55) and Yb (Z = 70), white-line peaks occur at the threshold due to a high

density of unfilled f-states (Fig. 3.48a). The M

4

–M

5

splitting and the M

5

/M

4

inten-

sity ratio increase with the atomic number (Brown et al., 1984; Colliex et al., 1985).

Above Z = 71, the M

4

and M

5

edges occur as rounded steps (Ahn, 2004), making

them harder to recognize.

M

23

edges of elements near the beginning of the fourth period (K to Ti) occur

below 40 eV, superimposed on a rapidly falling valence-electron background that

makes them appear more like plasmon peaks than typical edges. M

23

edges of the

elements V to Zn are fairly sharp and resemble K-edges (Hofer and Wilhelm, 1993);

M

1

edges are weak and are rarely observed in energy-loss spectra.

202 3 Physics of Electron Scattering

Fig. 3.47 (a) M

45

edges for E

0

= 80 keV and β = 10 mrad, according to Hartree–Slater calcula-

tions (Leapman et al., 1980). (b) M

45

edges of fifth-period elements measured with E

0

= 120 keV

and β = 5.7 mrad (Zaluzec, 1982)

Fig. 3.48 (a) Energy-loss spectrum of a lanthanum oxide thin film, recorded with 200-keV elec-

trons and collection semi-angle of 100 mrad, showing M

5

and M

4

white lines followed by M

3

and

M

2

edges. (b)O

45

edge of thorium recorded using 120-keV electrons and 100-mrad acceptance

angle. Reproduced from Ahn and Krivanek (1983)

N

67

,O

23

, and O

45

edges have been recorded for some of the heavier elements

(Ahn and Krivanek, 1983). In thorium and uranium, the O

45

edges are prominent

as a double-peak structure (spin–orbit splitting 10 eV) between 80- and 120-eV

energy loss; see Fig. 3.48b.

3.7 The Form of Inner-Shell Edges 203

3.7.2 Dipole Selection Rule

Particularly when a small collection aperture is employed, the transitions that

appear prominently in energy-loss spectra are mainly those for which the dipole

selection rule applies, as in the case of x-ray absorption spectra. From Eq. (3.145),

the momentum exchange is approximately q

min

≈ k

0

θ

E

= E/v for θ<

θ

E

, whereas the momentum exchange upon absorption of a photon of energy E

is q(photon) = E/c. The ratio of momentum exchange in the two cases is

therefore

q

min

/q(photon) ≈ c/v (3.161)

and is less than 2 for incident energies above 80 keV. Therefore the optical selection

rule l =±1 applies approximately to the energy-loss spectrum. This dipole rule

accounts for the prominence of L

23

edges (2p → 3d transitions) in transition metals

and their compounds (high density of d-states just above the Fermi level) and of M

45

edges in the lanthanides (high density of unfilled 4f states).

In the case of a large collection aperture, the momentum transfer can be several

times q

min

(the median scattering angle for inner-shell excitation is typically 5θ

E

;

see Fig. 3.41) and dipole-forbidden transitions are sometimes observed (Section

3.8.2). For example, sharp M

2

and M

3

peaks are seen in the spectrum of lanthanum

oxide (Fig. 3.48a), representing l = 2 transitions from the 3p core level to a high

density of unfilled 4f states. These peaks almost disappear when a small (1.6 mrad)

collection angle is used (Ahn and Krivanek, 1983).

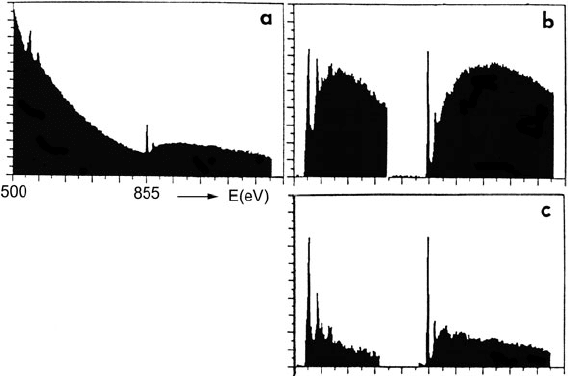

3.7.3 Effect of Plural Scattering

In discussing edge shapes, we have so far assumed that the specimen is very thin

(t/λ ≤ 0.3, where λ is the mean free path for all inelastic scattering) so that we

can ignore the possibility of a transmitted electron being inelastically scattered by

valence electrons, in addition to exciting an inner shell. In thicker samples, this sit-

uation no longer applies and a broad double-scattering peak appears at an energy

loss of approximately E

k

+ E

p

, where E

p

is the energy of the main “plasmon”

peak observed in the low-loss region. In even thicker specimens, higher order satel-

lite peaks merge with the double-scattering peak to produce a broad hump beyond

the edge, completely transforming its shape and obliterating any fine structure; see

Figs. 3.33 and 3.49. This behavior points to the advantage of using very thin spec-

imens for the identification of ionization edges and the analysis of fine structure.

Within limits, however, such plural or “mixed” scattering can be removed from the

spectrum by deconvolution (Section 4.3).

204 3 Physics of Electron Scattering

Fig. 3.49 (a) Energy-loss spectrum recorded from a thick (t/λ ≈ 1.5) specimen of nickel

oxide. (b) Oxygen-K and nickel-L edges, after background removal. (c) Edge profiles after plural

scattering was removed by Fourier ratio deconvolution (Zaluzec, 1983)

3.7.4 Chemical Shifts in Threshold Energy

When atoms combine to form a molecule or a solid, the outer-shell wavefunctions

change to become molecular orbitals or Bloch functions, their energy levels then

reflecting the overall chemical or crystallographic structure. Although core-level

wavefunctions are altered to a much smaller extent, the energy of the core level may

change by several electron volts, depending on the chemical and crystallographic

environment of the atom involved.

Core-level binding energies can be measured directly by x-ray photoelectron

spectroscopy (XPS). In this technique, a bulk specimen is illuminated with

monochromatic x-rays and an electron spectrometer is used to measure the kinetic

energies of photoelectrons that escape into the surrounding vacuum. The final state

of the electron transition therefore lies in a continuum far above the vacuum level

and is practically independent of the specimen. In the case of a compound, any

increase in binding energy of a core level, relative to its value in the pure (solid)

element, is called a chemical shift. For metallic core levels in oxides and most other

compounds, the XPS chemical shift is positive because oxidation removes valence-

electron charge from the metal atom, reducing the screening of its nuclear field and

deepening the potential well around the nucleus.

The ionization-edge threshold energies observed in EELS or in x-ray absorption

spectroscopy (XAS) represent a difference in energy between the core-level initial

state and the lowest energy final state of the excited electron. The corresponding

chemical shifts in threshold energy are more complicated than in XPS because the

lowest energy final state lies below the vacuum level and its energy depends on the

3.7 The Form of Inner-Shell Edges 205

valence-electron configuration. For example, going from a conducting phase (such

as graphite) to an insulator (diamond) introduces an energy bandgap, raising the

first-available empty state by several electron volts and increasing the ionization

threshold energy (Fig. 1.4). On the other hand, the edge threshold in many ionic

insulators corresponds to excitation to bound exciton states within the energy gap,

reducing the chemical shift by an amount equal to the exciton binding energy.

The situation is further complicated by a many-body effect known as relaxation.

When a positively charged core hole is created by inner-shell excitation, nearby

electron orbitals are pulled inward, reducing the magnitude of the measured binding

energy by an amount equal to the relaxation energy. In XPS, where the excited

electron leaves the solid, measured relaxation energies are s ome tens of electron

volts. In EELS or XAS, however, a core electron that receives energy just slightly

in excess of the threshold value remains in the vicinity of the core hole and the

screening effect of its negative charge reduces the relaxation energy. In a metal,

conduction electrons provide additional screening that is absent in an insulating

compound, so while relaxation effects may be less in EELS than in XPS, differences

in relaxation energy between a metal and its compounds can have an appreciable

influence on the chemical shift (Leapman et al., 1982).

Muller (1999) has pointed out that core-level shifts can be opposite in sign to

those expected from electronegativity arguments, and in binary alloys the shift can

be of the same sign for both elements. Measured core-level shifts in Ni–Al and

Ni–Si alloys were found to be proportional to valence band shifts deduced from

linear muffin-tin orbital calculations. In metals, therefore, the core-loss shift appears

to be largely determined by changes in the valence band, rather than by charge

transfer. The width of the valence band varies with changes in the type, number,

and separation of neighboring atoms, the core level tracking these valence band

shifts to within 0.1 eV. As a result, the EELS chemical shift is capable of providing

information about the occupied electronic states of a metal.

Measured EELS chemical shifts of metal-atom L

3

edges in transition metal

oxides are typically 1 or 2 eV and either positive or negative (Leapman et al., 1982).

The shifts of K-absorption edges in the same compounds are all positive and in the

range of 0.7–10.8 eV (Grunes, 1983). XAS chemical shifts, largely equivalent to

those registered by EELS, have been studied extensively. The absorption edge of

the metal atom in a compound is usually shifted to higher photon energy (compared

to the metallic element) and these positive chemical shifts range up to 20 eV (for

KMnO

4

) i n the case of K-edges of transition metals.

Because t ransition series elements can take more than one valency, there exist

mixed-valency compounds (e.g., Fe

3

O

4

and Mn

3

O

4

) containing differently charged

ions of the same species. Since the chemical shift increases with increasing oxida-

tion state, a double edge or multiple edges may be observed. In chromite spinel, for

example, the L

3

and the L

2

white lines are each split by about 2 eV because of the

presence of both Cr

2+

and Cr

3+

ions. Since these two ions occupy different sites

(tetrahedral and octahedral) within the unit cell, the observed splitting will include

a contribution (estimated as 0.7 eV) arising from the different site symmetry (Taftø

and Krivanek, 1982b).

206 3 Physics of Electron Scattering

Site-dependent chemical shifts can also occur in organic compounds in which

carbon atoms are present at chemically dissimilar sites within a molecule. For exam-

ple, the carbon K-edge recorded from a nucleic acid base shows a series of peaks,

interpreted as being the result of several edges chemically shifted relative to one

another due to the different effective charges on the carbon atoms (Isaacson, 1972b).

3.8 Near-Edge Fine Structure (ELNES)

Core-loss spectra recorded from solid specimens often s how a pronounced fine

structure, taking the form of peaks or oscillations in intensity within 50 eV of the

ionization threshold. Most of this structure reflects the influence of atoms surround-

ing the excited atom and requires a solid-state explanation. The basic principles are

described in several review articles (Brydson, 1991; Sawatzky, 1991; Rez, 1992;Rez

et al., 1995; M izuguchi, 2010). In the sections below, we outline several approaches

that have been used to interpret the fine structure in different types of material,

namely

1. the band structure approach, in which the final states of the excited core electron

are Bloch states in an infinite solid;

2. the multiple scattering concept, which considers backscattering of the excited

electron within a cluster of typically a few hundred atoms;

3. the molecular orbital picture, in which the final state involves just a few atoms;

4. multiplet processes, in which several electrons are involved, but all within the

same atom.

3.8.1 Densities-of-States Interpretation

Modulations of the single-scattering intensity J

k

1

(E) can be related to the band

structure of the solid in which scattering occurs. The theory is greatly simplified

by making a one-electron approximation: excitation of an inner-shell electron is

assumed to have no effect on the other atomic electrons. According to the Fermi

golden rule of quantum mechanics (Manson, 1978), the transition rate is then pro-

portional to a product of the density of final states N(E) and an atomic transition

matrix M(E):

J

1

k

(E) ∝ dσ/dE ∝|M(E)|

2

N(E) (3.162)

M(E) represents the overall shape of the edge, discussed in Section 3.7.1, and is

determined by atomic physics, whereas N(E) depends on the chemical and crystal-

lographic environment of the excited atom. To a first approximation, M(E) can be

assumed to be a slowly varying function of energy loss E, so that variations in J

1

k

(E)

represent the energy dependence of the densities of states (DOS) above the Fermi

level. However, the following qualifications apply.

3.8 Near-Edge Fine Structure (ELNES) 207

(1) Transitions occur only to a final state that is empty; like x-ray absorption spec-

troscopy, EELS yields information on the density of unoccupied states above

the Fermi level.

(2) Because the core-level states are highly localized, N(E)isalocal density of

states (LDOS) at the site of the excited atom (Heine, 1980). As a result, there

can be appreciable differences in fine structure between edges representing dif-

ferent elements in the same compound; see Fig. 3.50. Even in the case of a

single element, the fine structure may be different at sites of different symmetry,

as demonstrated by Tafto (1984) for Al in sillimanite.

(3) The strength of the matrix element term is governed by the dipole selection rule:

l =±1, with l = 1 transitions predominating (see Sections 3.7.2 and 3.8.2).

As a result, the observed DOS is a symmetry-projected density of states. Thus,

modulations in K-edge intensity (1s initial state) reflect mainly the density of 2p

final states. Similarly, modulations in the L

2

and L

3

intensities (2p initial states)

are dominated by 3d final states, except where p → d transitions are hindered

by a centrifugal barrier (for example, p → s transitions are observed close to

silicon L

23

threshold). As a result of this selection rule, a dissimilar structure can

be expected in the K- and L-edges of the same element in the same specimen.

(4) N(E) is in principle a joint density of states, the energy dependence of the final-

state density being convolved with that of the core level. The core-level width

i

is given approximately by the uncertainty relation

i

τ

h

≈ , where the lifetime

τ

h

of the core hole is determined by the speed of the de-excitation mechanism

Fig. 3.50 Dashed curves: near-edge fine structure calculated for cubic boron nitride using pseudo-

atomic orbital band theory. Solid curves: core-loss intensity measured by P. Fallon. From Weng

et al. (1989), copyright American Physical Society. Available at http://link.aps.org/abstract/PRB/

v40/p5694