Egerton R.F. Electron Energy-Loss Spectroscopy in the Electron Microscope

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

218 3 Physics of Electron Scattering

We assume that instrumental resolution is not a limiting factor and that the

effects of plural inelastic scattering of the transmitted electron are negligible or have

been removed by deconvolution to yield the single-scattering distribution J

1

k

(E), as

described in Chapter 4. The oscillatory part of the intensity (following the ionization

edge) is then represented in a normalized form as

χ(E) =

J

1

k

(E) − A(E)

/A(E) (3.166)

where A(E) is the energy-loss intensity that would be observed in the absence of

backscattering, as calculated using a single-atom model. Using Eq. (3.165), the

oscillatory component can also be written as a function χ( k) of the ejected-electron

wavevector. As in x-ray absorption, the main contribution to J

1

k

(E) is from dipole

scattering (Section 3.7.2), so the same theory can be used to interpret extended

energy-loss fine structure (EXELFS).

Approximating the ejected-electron wavefunction at the backscattering atom by

a plane wave and assuming that multiple backscattering can be neglected, EXAFS

theory gives (Sayers et al., 1971)

χ(k) =

j

N

j

r

2

j

f

j

(k)

k

exp(−2r

j

/λ

i

)exp(−2σ

2

j

k

2

)sin[2kr

j

+φ(k)] (3.167)

ThesummationinEq.(3.167) is over successive shells of neighboring atoms, the

radius of shell j being r

j

. The largest contribution comes from the nearest neighbors

(j = 1), unless these have a low scattering power (e.g., hydrogen). N

j

is the number

of atoms in shell j and the r-dependence of N

j

or N

j

/r

2

j

is the radial distribution

function (RDF) of the atoms surrounding the ionized atom. In the case of a perfect

single crystal, the RDF should consist of a series of delta functions corresponding

to discrete values of shell radius.

In Eq. (3.167), f

j

(k)isthebackscattering amplitude or form factor for elastic

scattering through an angle of π rad; it has units of length and can be calculated

(as a function of k), knowing the atomic number Z of the backscattering element.

The results of such calculations were tabulated by Teo and Lee (1979). For lower

Z elements, screening of the nuclear field can be neglected, so the backscattering

approximates to Rutherford scattering for which f (k) ∝ k

−2

, as shown by Eqs. (3.1)

and (3.3).

The damping term exp(−2r

j

/λ

i

)inEq.(3.167) represents inelastic scattering of

the ejected electron along its outward and return path, which changes the value

of k and thereby weakens the interference, so this inelastic scattering is some-

times referred to as absorption. Instead of incorporating a damping term explicitly

in Eq. (3.167), absorption can be included by making k into a complex quantity

whose imaginary part represents the inelastic scattering (Lee and Pendry, 1975).

Absorption arises from both electron–electron and electron–phonon collisions and

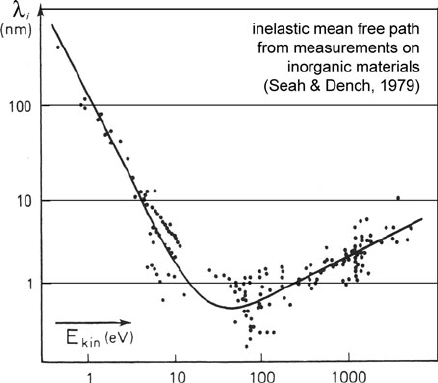

in reality the inelastic mean free path is a function of k (Fig. 3.57). Because the

mean free path is of the order of 1 nm for an electron energy of the order of 100 eV

3.9 Extended Energy-Loss Fine Structure (EXELFS) 219

Fig. 3.57 Mean free path for

inelastic scattering of an

electron, as a function of its

energy about the Fermi level.

The solid curve is a

least-squares fit to

experimental data obtained

from a variety of materials.

From Seah and Dench (1979),

copyright John Wiley and

Sons, Ltd

(see Fig. 3.57), inelastic scattering provides one limit to the range of shell radii that

can contribute to the RDF. Another limit arises from the lifetime τ

h

of the core

hole.

The Gaussian term exp(−2σ

2

j

k

2

)inEq.(3.167) is the Fourier t ransform of a

radial broadening function that represents broadening of the RDF due to thermal,

zero-point, and static disorder. The disorder parameter σ

j

differs from the Debye–

Waller parameter u

j

used in diffraction theory (see Section 3.1.5) because only the

radial component of relative motion between the central (ionized) and backscatter-

ing atom is of concern. In a single crystal, where atomic motion is highly correlated,

σ

j

may be considerably less than u

j

.Thevalueofσ

j

depends on the atomic number

of the backscattering atom and on the type of bonding; in an anisotropic material

such as graphite, it will also depend on the direction of the vector r

j

.

The last term in Eq. (3.167), sin[2 kr

j

+ φ

j

(k)], determines the interference con-

dition. The phase difference between the outgoing and reflected waves consists of

a path-length component 2π(2r

j

/λ) = 2 kr

j

and a component φ

j

(k) that accounts

for the phase change of the electron wave after traveling through the atomic field.

This phase change can in turn be split into two components, φ

a

(k) and φ

b

(k), that

arise from the emitting and backscattering atoms. These components can be cal-

culated using atomic wavefunctions, incorporating an effective potential to account

for exchange and correlation (Teo and Lee, 1979). In accordance with the dipole

selection rule, the emitted wave is expected to have p-symmetry in the case of K-

shell ionization and mainly d-symmetry in the case of an L

23

edge. The phase-shift

component φ

b

differs in these two cases.

Through Fourier transform and curve-fitting techniques (see Section 4.6),

Eq. (3.167), has enabled extended x-ray fine structure (EXAFS) to provide local

structural information from many materials. It represents a single-scattering,

220 3 Physics of Electron Scattering

plane-wave approximation but these limitations can be removed by generalizing the

backscattering amplitude f

j

(k)intoaneffective scattering amplitude, as described by

Rehr and Albers (2000) and as embodied in the FEFF computer code (Ankudinov

et al., 1998). This program calculates the inelastic scattering based on electron self-

energy concepts rather than using an empirical mean free path and also allows

for core-hole effects (including initial-state broadening), nondipole effects, thermal

vibrations, and crystalline anisotropy. Used on x-ray data, FEFF can give inter-

atomic separations to within 2 pm and coordination numbers to within ±1 (Rehr

and Albers, 2000). As it incorporates multiple scattering, it can also be used to ana-

lyze near-edge (XANES or NEXAFS) x-ray structure and has since been adapted to

energy-loss (EXELFS and ELNES) measurements; see Section 4.7.

3.10 Core Excitation in Anisotropic Materials

The properties of an anisotropic crystal vary with direction and it is possible to

measure this directionality by core-loss EELS, through appropriate choice of scat-

tering angle and specimen orientation. In the case of K-shell ionization, the p-type

outgoing wave representing the ejected electron probes the atomic environment

predominantly in the direction of the scattering vector q of the fast electron; see

Fig. 3.58. In other words, the contribution to the EXELFS modulations from atoms

that lie in the direction r

j

(making an angle ϕ with q) is given to a first approximation

(Leapman et al., 1981)by

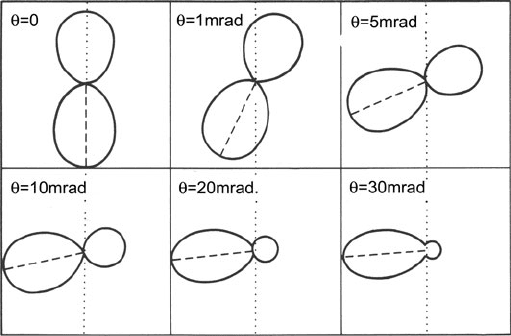

Fig. 3.58 Angular dependence of the ejected-electron intensity per unit solid angle, for carbon

K-shell ionization by 100-keV electrons, for an energy loss of 385 eV and various scattering angles.

The dashed line represents the direction of the scattering vector q of the fast electron, whose path

isshownbythedotted line. From Maslen and Rossouw (1983), copyright Taylor and Francis

3.10 Core Excitation in Anisotropic Materials 221

χ(k) ∝ (q ·r

j

)

2

∝ cos

2

ϕ (3.168)

For very small scattering angles (θ<<θ

E

), atoms lying along the direction of

the incident wavevector k

0

make the major contribution to χ(k), whereas at larger

scattering angles atoms lying perpendicular to k

0

contribute the most; see Fig. 3.58.

However, the scattered intensity in the second case is much less. To ensure equal

intensities in both spectra, a small collection aperture can be used to record the core-

loss spectrum at scattering angles of +θ and −θ relative to the optic axis. Choosing

θ to be equal to the characteristic angle (θ

E

= E/γ m

0

v

2

) results in the angle φ

between q and k

0

being ±45

◦

, since ϕ ≈ tan

−1

(θ/θ

E

) from geometry of the triangle

PQR in Fig. 3.39 (points S and R come together for s mall θ).

If the specimen is tilted 45

◦

relative to the incident beam, these ±θ spectra will

provide information weighted toward directions parallel and perpendicular to the

specimen plane. In the case of a hexagonal layer material such as graphite, this

means information about the bonding within and perpendicular to the basal-plane

layers. Orientation-dependent EXELFS spectra were first obtained from test spec-

imens of graphite (Disko, 1981) and boron nitride (Leapman et al., 1981). An

orientation dependence observed in the near-edge fine structure of boron nitride

(Leapman and Silcox, 1979) was interpreted in terms of the directionality of

chemical bonding.

Nonrelativistic expressions (Leapman et al., 1983) for the angular distribution of

the σ and π intensities, for a uniaxial specimen rotated through an angle about

the y-axis (see Fig. 3.60a), are

J(π ) ∝ cos

2

(φ −)/(θ

2

+θ

E

2

) (3.169)

J(σ ) ∝ sin

2

(φ −)/(θ

2

+θ

E

2

) (3.170)

For =0, J(π) ∝ θ

E

2

/(θ

2

+θ

E

2

)

2

,sotheπ-intensity has a narrow forward-peaked

angular distribution, falling by a factor of 4 between θ = 0 and θ = θ

E

. On the other

hand, J(σ ) ∝ θ

2

/(θ

2

+θ

E

2

)

2

for = 0, so the σ intensity is zero at θ = 0 and

rises to a maximum at θ ≈±θ

E

. The sum of these two components is Lorentzian.

Tilting the specimen makes the two angular distributions asymmetric, qualitatively

similar to the surface plasmon case (Fig. 3.22), and allows the two components to

be measured separately. Tilting to 45

◦

is advantageous because it maximizes the

separation between the two angular distributions and makes their relative intensities

similar; see Fig. 3.59a.

For a uniaxial crystal, Klie et al. (2003)haveintegratedthez-axis and basal-

plane (xy) intensities over all azimuthal angles and up to a scattering angle β.For

an electron beam parallel to the c-axis, these integrated intensities are equal when

β = θ

E

(solid curves in Fig. 3.59b).

Contour plots of the K-loss σ and π intensities, in both x- and y-directions in the

diffraction plane, are shown in Fig. 3.60b for specimen-tilt angles up to 45

◦

.Again,

tilting is seen to lead to anisotropy in the scattering pattern, the σ -intensity develop-

ing a “bean” shape, elongated parallel to the axis of tilt. These results illustrate how

222 3 Physics of Electron Scattering

Fig. 3.59 (a) Calculated and measured angular distributions of π and σ intensities in the K-loss

spectrum of graphite, within the plane of tilt and for specimen oriented with a tilt angle γ = –45

◦

(Leapman et al.,1983). Available at http://link.aps.org/abstract/PRB/v28/p2361.(b)Axial(z)and

basal-plane (xy) intensities as a function of collection angle (Klie et al., 2003). Reprinted with

permission, copyright American Physical Society. Available at http://link.aps.org/abstract/PRB/

v67/p144508

energy-filtered diffraction might be used to probe the bonding in small volumes of

anisotropic materials (Browning et al, 1991b; Klie et al., 2003; Botton, 2005; Saitoh

et al., 2006).

A near-parallel incident beam (small convergence angle α) is needed to obtain

good momentum resolution but this implies a limit on the spatial resolution:

Fig. 3.60 (a) Specimen geometry in relation to the recording plane of an energy-filtered diffraction

pattern. (b) Intensity in the diffraction plane, calculated from Eqs. (3.169)and(3.170)for1s → π

∗

and 1s → σ∗ transitions in a hexagonal crystal, for three values of the y-axis specimen t ilt .The

optic axis (forward-scattering direction) is indicated by the small white dot in the center of each

pattern. The area of each image is (10 ×10)θ

E

. From Radtke et al. (2006), copyright Elsevier

3.11 Delocalization of Inelastic Scattering 223

x ≈ 0.6λ/α, as given by the Rayleigh criterion (or the uncertainty principle).

Using Bragg’s law (λ = 2d

hkl

θ

B

= d

hkl

θ), the fractional angular or momentum

resolution is (Egerton, 2007)

q/q

B

= θ/θ = 2α/θ = (1.2λ/x)(d

hkl

/λ) ≈ 1.2d

hkl

/x (3.171)

where q

B

is the wave number corresponding to a Brillouin-zone boundary and d

hkl

is

the corresponding lattice-plane spacing. For 10% momentum resolution, the spatial

resolution is limited to x ≈ 12d

hkl

, amounting to 1 nm or more for a typical

material and crystallographic direction. Midgley (1999) described a method for

obtaining angular resolution down to a few microradians by using an aperture of

diameter d in the TEM image plane. It involves raising the specimen a distance z

above the focus plane of the electron probe, resulting in a spatial resolution limit of

x = 2αz, where α is the convergence semi-angle of the probe. From the Rayleigh

criterion, the smallest useful aperture diameter is d ≈ 0.6λ/α, giving an angu-

lar resolution θ = d/z ≈ 0.6λ/(αz) ≈ 1.2λ/x and a fractional resolution

(θ)/θ = (1.2λ/x)(d

hkl

/λ) ≈ 1.2d

hkl

/x, consistent with Eq. (3.171).

Although the orientation dependence of the energy-loss spectrum can be advan-

tageous, it is also useful to collect a spectrum that is characteristic of the specimen

and independent of its orientation. This can be done by using a collection semi-

angle β equal to the so-called magic angle θ

m

. For a hexagonal layer material

such as graphite, this means that the two components σ and π are suitably aver-

aged, such that the core-loss spectrum is independent of the specimen orientation

(Fig. 3.60a). In fact, this spectrum is the same as that of a polycrystalline mate-

rial with grains randomly oriented. The value of θ

m

is small: early estimates ranged

from 1.36θ

E

to 4θ

E

. The latter value is now known to be correct only at very low

incident energy, and relativistic theory predicts a rapid fall in θ

m

/θ

E

with increasing

incident energy; see Appendix A.

3.11 Delocalization of Inelastic Scattering

The long-range nature of the electrostatic force responsible for inelastic scatter-

ing imposes a basic limit on the spatial r esolution obtainable in an energy-selected

image or through small-probe analysis. This delocalization of the scattering can be

defined as the width of the real-space distribution of scattering probability, some-

times called an object function (Pennycook et al., 1995b) or pragmatically as the

blurring of an inelastic image after all instrumental aberrations and elastic effects

have been accounted for (Muller and Silcox, 1995a).

On a classical (particle) description of scattering, delocalization is represented

through the impact parameter b of the incident electron (Fig. 3.1). Small b implies

a strong electrostatic force and large scattering angle, so scattering should appear

more localized if observed using an off-axis detector (Howie, 1981; Rossouw and

Maslen, 1984), in accord with channeling studies; see Section 5.6.1.Thisclas-

sical approach was initiated by Bohr (1913), who derived an expression for the

224 3 Physics of Electron Scattering

energy exchange E(b) between an incident electron (traveling in a straight line with

speed v) and a bound atomic electron, represented as a classical oscillator with

angular frequency ω:

E(b) ∝ (ω/v)

2

{[K

0

(bω/v)]

2

+K

1

[bω/v]

2

} (3.172)

For b << (v/ω), E(b) ∝ 1/b

2

; in fact, the energy exchange is just the Rutherford

recoil energy that would be imparted to a stationary and free electron, since the

interaction time (≈ b/v) is short compared to the oscillation period (2πω)

−1

of the

atomic electron. For b >> (ω/v), E(b) ∝ exp(−2bω/v); now the atomic electron

has time to adjust to the electric field, resulting in little energy exchange (adiabatic

conditions). According to these classical arguments, inelastic scattering is therefore

confined to impact parameters below b

max

≈ ω/v. The classical theory was further

developed and made relativistic by Jackson (1975), who gives b

max

= γv/ω.

The wave nature of the electron can be introduced by applying the Heisenberg

uncertainty principle to the scattering event: px ≈ h, where p represents

momentum uncertainty in the x-direction (perpendicular to the incident electron

beam) and x is interpreted as the x-delocalization. An early suggestion (Howie,

1981) was to take p = q ≈ k

0

θ

E

= (h/λ)θ

E

,givingx = λ/θ

E

. However,

this leads to delocalization of 20–50 nm for plasmon losses, now thought to be too

large. In fact, θ

E

is not a typical inelastic scattering angle; the mean and median

angles are an order of magnitude larger (see Section 3.3.1), leading to smaller x.

This argument is developed further in Section 5.5.3. Here we present a simplified

wave-optical treatment of delocalization that accounts for the essential features of

the object or point-spread function associated with inelastic scattering.

In light optics, the far-field (Fraunhofer) diffraction pattern represents a Fourier

transform of the diffracting object. A familiar example i s a circular hole (diameter a)

in an opaque screen, whose aperture function is a rectangular (top-hat) function. The

two-dimensional Fourier transform (representing amplitude at a distance r from the

optic axis, measured at a large distance R) is then of the form J

1

(x)/x, where J

1

is

a first-order Bessel function, x = k

0

ar/R, and k

0

= 2π/λ is the wave number of

the radiation. When squared, this amplitude gives an Airy function whose radius

(measured to the first zero of intensity) corresponds to k

0

ar/R = 3.83. Writing

r/R = sin θ , where θ is the angle of diffraction (small for λ<<a), the width of

the scattering object is seen to be

a = 3.83(λ/2π)/ sin θ ≈ 0.61 λ/θ (3.173)

Equation (3.173) indicates that the angular width of scattering is inversely propor-

tional to the size of the diffracting object; it coincides with the Rayleigh resolution

limit of an optical system of angular aperture θ, for the case of incoherent radiation.

Somewhat larger values of the coefficient in Eq. (3.173) are expected for coherent

or partially coherent illumination (Born and Wolf, 2001).

More generally, the amplitude distribution at the exit plane of a scattering object

(the aperture function in Fourier optics) is

3.11 Delocalization of Inelastic Scattering 225

A(r) ∝ FT2[dψ/d] (3.174)

where FT2 represents a two-dimensional Fourier transform and dψ/d is the scat-

tered amplitude per unit solid angle. For a single scattering object, such as an atom,

the product A(r)A

∗

(r) can be regarded as an object or point-spread function (PSF)

that represents the image-intensity distribution in the case of an ideal lens system

and parallel (plane-wave) illumination. If we assume A(r) = A

∗

(r), neglecting any

change in phase with scattering angle, the PSF can be obtained from

PSF(r) ∝ A(r)A

∗

(r) ∝{FT2[dI/d]

1/2

}

2

(3.175)

with dI/d the scattered intensity per unit solid angle. For radially symmetric scat-

tering, the two-dimensional Fourier transform can be written in terms of a single

integral involving a J

0

Bessel function.

Applying Eq. (3.175)totheinelastic scattering of fast electrons (Shuman et al.,

1986), where (dI/d) ∝ (θ

2

+θ

E

2

)

−1

is a good approximation over most of the

angular range, the Fourier transform has an analytical solution:

PSF(r) ∝ (k

0

r)

−2

exp(−2k

0

θ

E

r) = (k

0

r)

−2

exp(−2r/b

max

) (3.176)

In other words, the PSF is an inverse square function multiplied by an exponential

term that introduces an additional factor of 1/e

2

= 0.135 at r = b

max

, where b

max

=

(k

0

θ

E

)

−1

= v/ω is the Bohr adiabatic limit. This exponential attenuation was veri-

fied by Muller and Silcox (1995a), who measured the intensity beyond the edge of

an oxidized SiO

2

film; see Fig. 3.61. They obtained b

max

= b

1

E

1.0064

, with energy

loss E in eV and b

1

= 125 nm (b

1

= 129 nm expected if b

max

= γv/ω). This r

–2

dependence at lower r is consistent with hydrogenic calculations of Ritchie (1981)

and Wentzel-potential calculations of Rose (1973), summing over all energy loss.

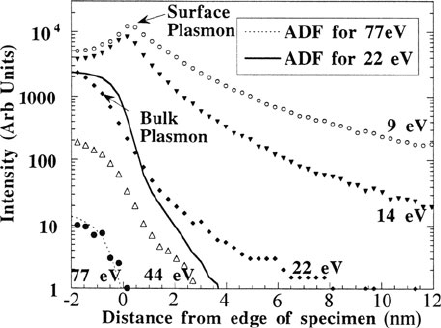

Fig. 3.61 Measurements of

inelastic intensity as a

function of distance from the

edge of a 3-nm amorphous

carbon specimen. The surface

plasmon intensity at 9 and

14 eV has a maximum at the

edge, resulting in a

diminution of the bulk

plasmon intensity, as in

Fig. 3.25. From Muller and

Silcox (1995a), copyright

Elsevier

226 3 Physics of Electron Scattering

Due to decrease in the oscillator strength, the angular distribution of inelastic

scattering falls of more rapidly than the Lorentzian function at large scattering

angles, which removes the singularity in Eq. (3.176)atr =0. For atomic transitions,

this cutoff occurs not far from the Bethe r idge angle θ

r

≈ (E/E

0

)

1/2

≈ (2θ

E

)

1/2

.

Using Eq. (3.175) with dI/d ∝ (θ

2

+θ

E

2

)

−1

(θ

2

+θ

r

2

)

−1

gives a PSF with a

sharp central peak and tails that extend over atomic dimensions for typical core-loss

scattering, or stretch beyond 1 nm for valence-electron losses, as shown in Fig. 3.62.

The inelastic object function can also be calculated from first principles (Maslen

and Rossouw, 1983, 1984; Kohl and Rose, 1985; Muller and Silcox, 1995a; Cosgriff

et al., 2005; Findlay et al., 2005; Xin et al., 2010). In general, it appears to

approximate to a Lorentzian function with exponentially attenuated tails:

PSF(r) ∝ (1 + r

2

/r

0

2

)

−1

exp(−2k

0

θ

E

r) (3.177)

where r

0

is inversely related to the cutoff θ

r

in the Lorentzian angular distribution.

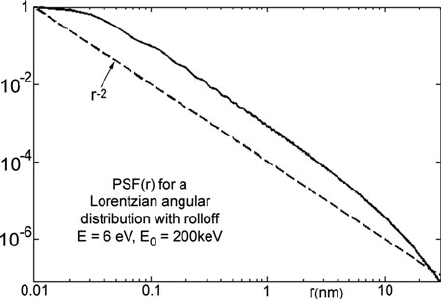

For low energy losses, θ

r

>> θ

E

and the radial dependence is close to r

–2

over a

considerable range, a large fraction of the intensity being present in the PSF tails;

see Fig. 3.62. At high energy loss, θ

r

/θ

E

is smaller and more of the intensity lies

within the central peak.

The above equations assume that all angles of scattering are recorded. If the

imaging system contains an angle-limiting aperture, the angular width of scatter-

ing is reduced and the PSF is broadened. For a very small collection aperture, the

angular distribution becomes rectangular and the PSF width should be given by

Eq. (3.173). For energy losses far above a major ionization edge, the angular dis-

tribution of inelastic scattering departs from Lorentzian, becoming a Bethe ridge

(Fig. 3.36), which should lead to a more localized signal (Kimoto et al., 2008).

The delocalization of inelastic scattering has various consequences for TEM-

EELS analysis. When a small (sub-nanometer) electron probe is incident on a

specimen, the energy-loss spectrum will contain contributions from outside the

Fig. 3.62 Inelastic PSF for

E = 6eVandE

0

= 200 keV,

computed for a Lorentzian

angular distribution of

inelastic scattering with a

(θ

2

+θ

r

2

)

−1

rolloff at

θ

r

≈ (2 θ

E

)

1/2

≈ 2mrad.The

dashed line in the logarithmic

plot represents a 1/r

2

dependence

3.11 Delocalization of Inelastic Scattering 227

probe, especially at low energy loss where the angular distribution of inelastic scat-

tering is narrow and the PSF correspondingly broad. Aloof excitation of surface

plasmons (Section 3.3.6) represents a special case of this. In the case of energy-

selected elemental maps, atomic resolution is possible only for higher E edges,

where θ

E

exceeds about 2 mrad and the width of the central peak of the PSF is

below 0.2 nm. For high-Z elements, the average energy loss amounts to several hun-

dred electron volts and a considerable fraction of the intensity occurs within the

central peak of the PSF, allowing the possibility of secondary electron imaging of

single atoms (Inada et al., 2011).

In the case of crystalline specimens thicker than a few nanometers, a detailed

description of core-loss imaging requires a more sophisticated treatment. Inelastic

scattering is represented in terms of a nonlocal potential W(r, r

),afunctionof

two independent spatial coordinates (r and r

), and related to a density matrix

(Schattschneider et al., 1999) or mixed dynamical form factor (Kohl and Rose,

1985; Schattschneider et al., 2000). The MDFF represents a generalization of the

dynamic form factor, necessary in crystals because the inelastically scattered waves

are mutually coherent and interfere with each other. Equation (3.20) then becomes

dσ

d

∝

ψ

∗

0

(r, z) W(r, r

) ψ

0

(r

, z) dr dr

dz (3.178)

where t he integrations are over radial coordinates perpendicular to the incident beam

direction z and over specimen thickness (0 < z < t). Equation (3.178) incorporates

the effect of the phase of the transmitted electron and its diffraction by the specimen,

making the cross section sensitive to the angle between the electron and the crystal.

If the spectrometer collection aperture cuts off an appreciable part of the scatter-

ing, the inelastic intensity is not in general proportional to the z-integrated current

density, implying that energy-filtered STEM images cannot always be interpreted

visually and may require computer modeling to be understood on an atomic scale

(Oxley and Pennycook, 2008; Wang et al., 2008c).

One feature appearing in such calculations is a volcano or donut structure (a dip

in intensity at the center of an atom or atomic column), which arises in the case of

a limited collection angle because electrons incident at the atomic center are scat-

tered preferentially to higher angles and are intercepted by the collection aperture

(D’Alfonso et al., 2008). The fact that an off-axis detector provides a more local-

ized inelastic signal was verified experimentally by Muller and Silcox (1995a). The

practical importance of delocalization for elemental analysis, in combination with

other resolution-limiting factors, is discussed further in Section 5.5.

Simplifying the situation by treating elastic and inelastic scattering separately,

we can expect a reasonable probability of an electron undergoing both types of

scattering, unless the specimen is ultrathin (<10 nm). As elastic scattering involves

relatively high angles and is more localized, contrast with high spatial frequency can

therefore occur in an inelastic image. Examples include the appearance of diffrac-

tion contrast in a plasmon-loss image (Egerton, 1976c) and phase-contrast lattice

fringes in a core-loss image (Craven and Colliex, 1977). Since it arises from double