Egerton R.F. Electron Energy-Loss Spectroscopy in the Electron Microscope

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

188 3 Physics of Electron Scattering

is forward peaked (maximum intensity at θ = θ, q = q

min

≈ kθ

E

and corresponds

to the dipole region of scattering. On a particle model, t his low-angle scattering

represents “soft” collisions with relatively large impact parameter.

At large energy loss, the scattering becomes concentrated into a Bethe ridge

(Fig. 3.36) centered around a value of q that satisfies

(qa

0

)

2

= E/R +E

2

/(2m

0

c

2

R) ≈ E/R (3.131)

for which the equivalent scattering angle θ

r

is given (Williams et al., 1984)by

sin

2

θ

r

= (E/E

0

)[1 +(E

0

−E)/(2m

0

c

2

)]

−1

(3.132)

or θ

r

≈ (E/E

0

)

1/2

≈ (2 θ

E

)

1/2

for small θ and nonrelativistic incident elec-

trons. This high-angle scattering corresponds to “hard” collisions with small impact

parameter, where the interaction involves mainly the electrostatic field of a single

inner-shell electron and is largely independent of the nucleus. In fact, the E−q rela-

tion represented by Eq. (3.131) is simply that for Rutherford scattering by a free,

stationary electron; the nonzero width of the Bethe ridge reflects the effect of nuclear

binding or (equivalently) the nonzero kinetic energy of the i nner-shell electron.

The energy dependence of the GOS is obtained by taking cross sections through

the Bethe surface at constant q. In particular, planes corresponding to very small

values of q (left-hand boundary of Fig. 3.36) give the inner-shell contribution

df

k

(0, E)/dE to the optical oscillator strength per unit energy df (0, E)/dE, which

is proportional to the photoabsorption cross section σ

0

:

df (0, E)/dE = df

k

(0, E)/dE +(df /dE)

= σ

0

/C (3.133)

where (df /dE)

represents a background contribution from outer shells of lower

binding energy and C = 1.097 × 10

−20

m

2

eV (Fano and Cooper, 1968).

Experimental values of photoabsorption cross section have been tabulated (Hubbell,

1971; Veigele, 1973) and can be used to test the results of single-atom calculations

of the GOS.

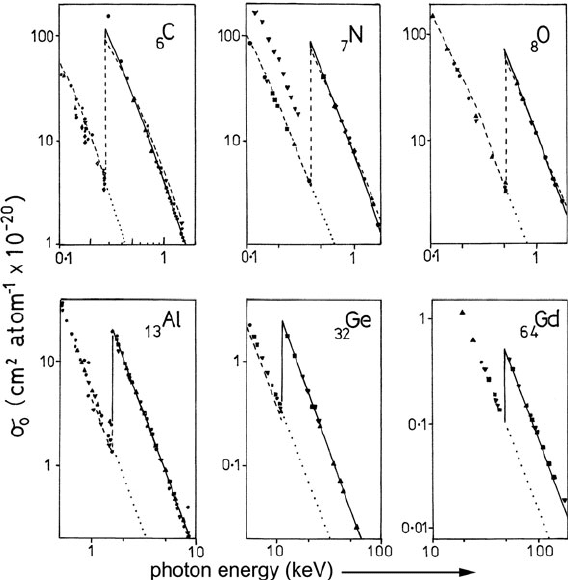

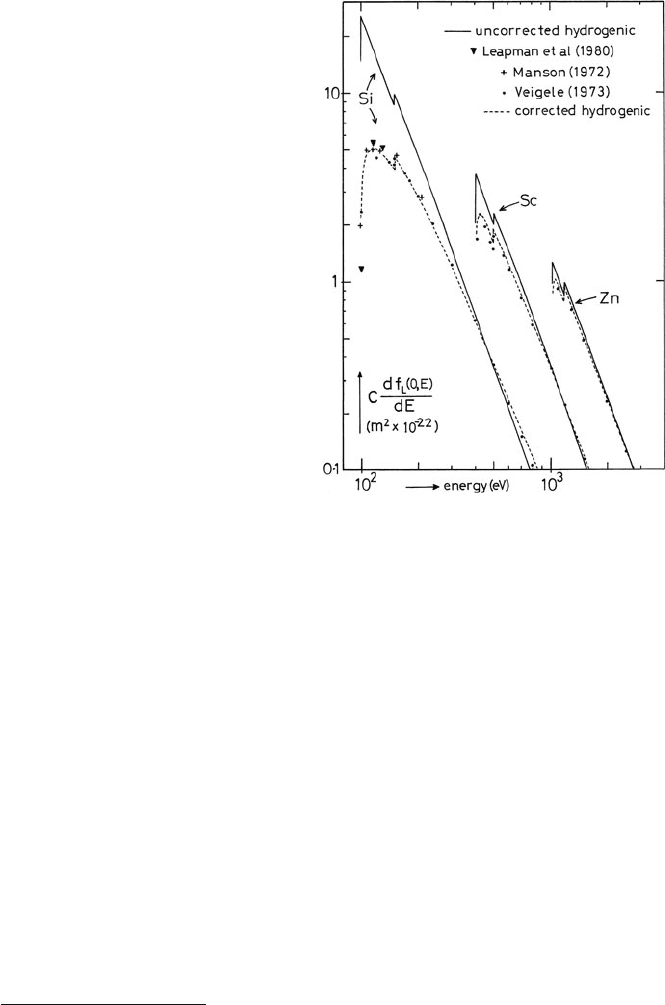

Such a comparison is shown in Figs. 3.37 and 3.38.ForK-shell ionization, a

hydrogenic calculation predicts quite well the overall shape of the absorption edge

and the absolute value of the photoabsorption cross section. In the case of L-shells,

the hydrogenic model gives too large an intensity just above the absorption thresh-

old (particularly for the lighter elements) and too low a value at high energies. This

discrepancy arises from the oversimplified treatment of screening in the hydro-

genic model, where the effective nuclear charge Z

s

is taken to be independent of

the atomic coordinate r. In reality, energy losses just above the threshold involve

interaction further from the nucleus, where the effective charge is smaller (because

of outer-shell screening), giving an oscillator strength lower than the hydrogenic

value. Conversely, energy losses much larger than E

k

correspond to close collisions

for which Z

s

approaches the full nuclear charge, resulting in an oscillator strength

slightly higher than the hydrogenic prediction. Also, for low-Z elements, the L

23

3.6 Atomic Theory of Inner-Shell Excitation 189

Fig. 3.37 K-shell x-ray absorption edges of several elements. Dotted lines represent the extrap-

olated background and solid lines denote the photoabsorption cross section calculated using a

hydrogenic model. The experimental data points are taken from Hubbell (1971)andthedashed

lines represent Hartree–Slater calculations of McGuire (1971). From Egerton (1979), copyright

Elsevier

absorption edge has a rounded shape (Fig. 3.38) due to the influence of the “cen-

trifugal” term

2

l

(l

+ 1)2m

0

r

2

in the effective potential; see Eq. (3.128). To be

useful for L-shells, the hydrogenic model requires an energy-dependent correction

chosen to match the observed edge shape of each element (Egerton, 1981a). The

correction is even larger in the case of M-shells (Luo and Zeitler, 1991).

The Hartree–Slater model takes proper account of screening and gives a good

prediction of the edge shape in many elements (Fig. 3.38). In other cases (e.g.,

L

23

-edges of transition metals) the agreement is worse, owing to the fact that

the calculations usually deal only with ionizing transitions to the continuum and

neglect excitation to discrete (bound) states just above the absorption threshold

(Section 3.7.1). Moreover, a free-atom model cannot predict the solid-state fine

structure which becomes prominent close to the threshold (Section 3.8).

At large q, a constant-q section of the Bethe surface intersects the Bethe ridge

(Fig. 3.36). As a result, the energy-loss spectrum of large-angle scattering contains a

190 3 Physics of Electron Scattering

Fig. 3.38 L-shell

photoabsorption cross

section, as predicted by

hydrogenic calculations

(Egerton, 1981a) and by the

Hartree–Slater model

(Manson, 1972; Leapman

et al., 1980). Experimental

data points (Veigele, 1973)

are also shown. From Egerton

(1981a), copyright Claitor’s

Publishing, Baton Rouge,

Louisiana

broad peak that is analogous to the Compton profile for photon scattering and whose

shape reflects the momentum distribution of the atomic electrons; see Section 5.6.7.

If df/dE is known as a function of q and E, the angular and energy dependence

of scattering can be calculated from Eq. (3.26), provided the relationship between q

and the scattering angle θ is also known.

3.6.2 Relativistic Kinematics of Scattering

In the case of elastic scattering, conservation of momentum leads to a simple rela-

tion between the magnitude q of the scattering vector and the scattering angle θ

(see Fig. 3.2), a given value of q corresponding to a single value of θ. In the case

of inelastic scattering, the value of q depends on both the scattering angle and the

energy loss.

3

The relationship between q and θ is derived by applying the conser-

vation of both momentum and energy to the collision. Since a 100-keV electron

has a velocity more than half the speed of light and a relativistic mass 20% higher

than its rest mass, it is necessary to use relativistic kinematics to derive the required

3

This indicates an additional degree of internal freedom, which on a classical (particle) model of

scattering corresponds to the interaction between the incident and atomic electrons taking place at

different points within the electron orbit.

3.6 Atomic Theory of Inner-Shell Excitation 191

relationship. At incident energies above 300 keV, further relativistic effects become

important, as discussed in Appendix A.

3.6.2.1 Conservation of Energy

The total energy W of an incident electron (=kinetic energy E

0

+ rest energy m

0

c

2

)

is given by the Einstein equation:

W = γ m

0

c

2

(3.134)

where γ = (1 −v

2

/c

2

)

−1/2

. The incident momentum is

p = γ m

0

v = k

0

(3.135)

Combining Eqs. (3.134) and (3.135)gives

W = [(m

0

c

2

)

2

+p

2

c

2

]

1/2

= [(m

0

c

2

)

2

+

2

k

2

0

c

2

]

1/2

(3.136)

Conservation of energy dictates that

W −E = W

= [(m

0

c

2

)

2

+

2

k

2

1

c

2

]

1/2

(3.137)

where W

and k

1

are the total energy and wave number of the scattered electron, E

being the energy loss. Using Eq. (3.136)inEq.(3.137) leads to an equation relating

the change in magnitude of the fast-electron wavevector to the energy loss

4

:

k

2

1

= k

2

0

−2E[m

2

0

/

4

+k

2

0

/(c)

2

]

1/2

+E

2

/(c)

2

= k

2

0

−2γ m

0

E/

2

+E

2

/(c)

2

(3.138)

Note that this relationship is independent of the scattering angle.

For numerical calculations, it is convenient to convert each wave number to a

dimensionless quantity by multiplying by the Bohr radius a

0

. Making use of the

equality Ra

2

0

=

2

/2m

0

, where R is the Rydberg energy, Eq. (3.138) becomes

(k

1

a

0

)

2

= (k

0

a

0

)

2

−(E/R)[γ −E/(2m

0

c

2

)] (3.139)

The E

2

term in Eq. (3.139) is insignificant for most inelastic collisions. The value

of (k

0

a

0

)

2

is obtained from the kinetic energy E

0

of the incident electron:

(k

0

a

0

)

2

= (E

0

/R)(1 +E

0

/2m

0

c

2

) = (T/R)/(1 −2T/m

0

c

2

) (3.140)

4

For Rutherford scattering from a free electron (where E =

2

q

2

/2m

0

) and low incident energies

(such that E

0

= k

2

0

/2m

0

), Eq. (3.138) becomes k

2

1

= k

2

0

− q

2

, indicating that the angle between

q and k

1

is 90

◦

. In this case, q goes to zero for θ → 0 (see Fig. 3.39), as implied by Eqs. (3.131)

and (3.132).

192 3 Physics of Electron Scattering

where T = m

0

v

2

/2 is an “effective” incident energy, useful in the equations

that follow.

3.6.2.2 Conservation of Momentum

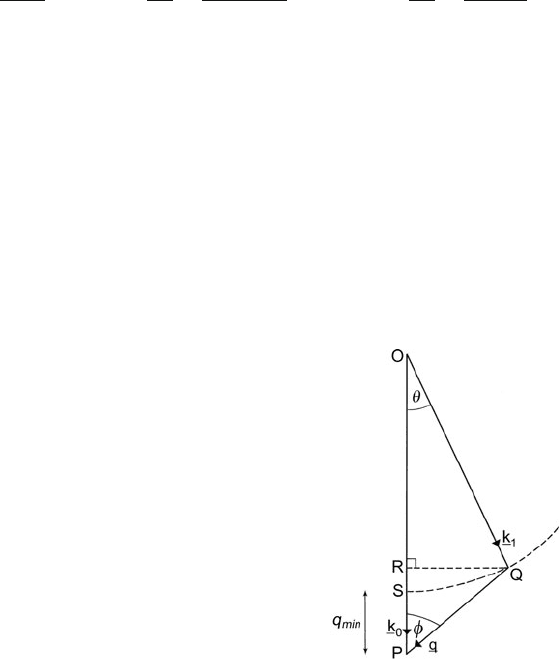

Momentum conservation is incorporated by applying the cosine rule to the vector

triangle (Fig. 3.39), giving

q

2

= k

2

0

+k

2

1

−2k

0

k

1

cos θ (3.141)

Taking a derivative of this equation gives (for constant E and E

0

)

d(q)

2

= 2k

0

k

1

sin θ dθ = (k

0

k

1

/π) d (3.142)

Substituting Eq. (3.138) into Eq. (3.141) then gives

(qa

0

)

2

=

2Tγ

2

R

1 −

1 −

E

γ T

+

E

2

2γ

2

Tm

0

c

2

1/2

cos θ

−

Eγ

R

+

E

2

2Rm

0

c

2

(3.143)

Equation (3.143) can in principle be used to compute qa

0

for any value of θ ,but

for small θ this procedure requires high-precision arithmetic, since evaluation of the

brackets in Eq. (3.143) involves subtracting almost identical numbers. For θ = 0,

corresponding to q = q

min

= k

0

−k

1

, binomial expansion of the square root in Eq.

(3.143) shows that terms up to second order in E cancel, giving

(qa

0

)

2

min

≈ E

2

/4RT +E

3

/(8γ

3

RT

2

) (3.144)

For γ

−3

E/T 1 (which applies to practically all collisions), only the E

2

term is of

importance and Eq. (3.144) can be written in the form

Fig. 3.39 Vector triangle for

inelastic scattering. The

dashed circle represents the

locus of point Q that defines

the different values of q and θ

possible for a given value of

k

1

, equivalent to a given

energy loss; see Eq. (3.138).

For E << E

0

and small θ ,

RP ≈ SP ≈ k

0

θ

E

and

RQ ≈ k

1

θ ≈ k

0

θ; applying

the Pythagoras rule to the

triangle PQR then leads to

Eq. (3.147)

3.6 Atomic Theory of Inner-Shell Excitation 193

q

min

≈ k

0

θ

E

(3.145)

where θ

E

= E/(2γ T) = E /( γ m

0

v

2

) is the characteristic inelastic scattering angle.

For a nonzero scattering angle, it is convenient to evaluate the corresponding

value of q from

(qa

0

)

2

= (k

0

a

0

−k

1

a

0

)

2

+2(k

0

a

0

)(k

1

a

0

)(1 −cos θ)

= (qa

0

)

2

min

+4(k

0

a

0

)(k

1

a

0

)sin

2

(θ/2)

∼

=

(qa

0

)

2

min

+4γ

2

(T/R)sin

2

(θ/2)

(3.146)

For θ 1 rad, Eq. (3.146) is equivalent to

q

2

≈ q

2

min

+4k

2

0

(θ/2)

2

≈ k

2

0

(θ

2

+θ

2

E

) (3.147)

Equation (3.147) is valid outside the dipole region, provided sin θ ≈ θ and is

relativistically correct provided θ

E

is defined as E/pv = E/(2γ T) rather than as

E/2E

0

.

3.6.3 Ionization Cross Sections

For θ 1 rad, the energy-differential cross section can be obtained by integrating

Eq. (3.29) up to an appropriate collection angle β:

dσ

dE

≈

4R

2

Em

2

0

v

2

β

0

df (q, E)

dE

2 πθ(θ

2

+θ

2

E

)

−1

dθ (3.148)

Within the dipole region of scattering, where (qa

0

)

2

< 1 (equivalent to β<10 mrad

at the carbon K-edge, for 100-keV incident electrons), the GOS is approximately

constant and equal to the optical value df (0, E)/dE,soEq.(3.148) becomes

dσ

dE

=

4πa

2

0

R

2

ET

df (0, E)

dE

ln

1 +(β/θ

E

)

2

(3.149)

To evaluate Eq. (3.148) outside the dipole region, df /dE is computed for each angle

θ, related to q by Eq. (3.141)or(3.147).

Alternatively, q or qa

0

can be used as the variable of integration. From Eq. (3.26)

and (3.142), we have

dσ

dE

≈

4πγ

2

R

Ek

2

0

df (q, E)

dE

d(q

2

)

q

2

(3.150)

= 4πa

2

0

E

R

−1

T

R

−1

df (q, E)

dE

d[ln (qa

0

)

2

] (3.151)

194 3 Physics of Electron Scattering

where T = m

0

v

2

2, R =

2

/(2m

0

a

2

0

) = 13.6 eV, and the limits of integration are,

from Eqs. (3.144) and (3.146),

(qa

0

)

2

min

≈ E

2

/(4RT) (3.152)

(qa

0

)

2

max

∼

=

(qa

0

)

2

min

+4γ

2

(T/R)sin

2

(β/2) (3.153)

Integration over a logarithmic grid, as implied by Eq. (3.151), is convenient for

numerical evaluation, since in the dipole region dσ/dE peaks sharply at small angles

but varies much more slowly at larger θ. Equation (3.151) reveals that the energy-

differential cross section is proportional to the area under a constant-E section

through the Bethe surface between (qa

0

)

min

and (qa

0

)

max

.

5

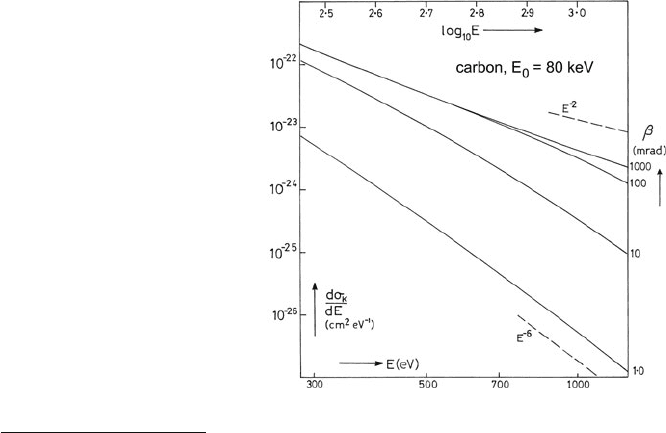

A computation of dσ/dE is shown in Fig. 3.40. Logarithmic axes are used in

order to illustrate the approximate behavior:

dσ/dE ∝ E

−s

(3.154)

where s is the downward slope in Fig. 3.40 and is constant over a limited range of

energy loss. The value of s is seen to depend on the size of the collection aperture,

an effect that has been confirmed experimentally (Maher et al., 1979).

For large β, such that most of the inner-shell scattering contributes to the loss

spectrum, s is typically about 3 at the ionization edge (E = E

k

), decreasing toward

2 with increasing energy loss. This asymptotic E

−2

behavior reflects the fact that for

Fig. 3.40 Energy-differential

cross section for K-shell

ionization of carbon

(E

K

= 284 eV), calculated

for different collection

semi-angles β using

hydrogenic wavefunctions;

dσ

K

/dE represents the K-loss

intensity, after subtracting the

background to the

K-ionization edge. From

Egerton (1979), copyright

Elsevier

5

The volume under the Bethe surface is a measure of the electron stopping power.

3.6 Atomic Theory of Inner-Shell Excitation 195

E E

k

practically all the scattering lies within the Bethe ridge and approximates

to Rutherford scattering from a free electron, for which dσ/dE ∝ q

−4

∝ E

−2

.

For small β, s increases with increasing energy loss, the largest value (just

over 6) corresponding to large E and very small β. Equation (3.148)givesdσ/dE ∝

E

−1

θ

−2

E

df (0, E)/dE ∝ E

−3

df (0, E)/dE for very small β, while df (0, E)/dE ∝

E

−3.5

for K-shell excitation and E →∞(Rau and Fano, 1967), so an asymptotic

E

−6.5

behavior would be expected.

For thin specimens in which plural scattering is negligible, the inner-shell contri-

bution to the energy loss spectrum (recorded with a collection semi-angle β)isthe

single-scattering intensity J

1

k

(β, E ) given by

J

1

k

(β, E ) = NI

0

dσ/dE (3.155)

where N is the number of atoms per unit specimen area contributing to the ionization

edge and I

0

is the integrated zero-loss intensity.

3.6.3.1 Partial Cross Section

For quantitative elemental analysis, the inner-shell intensity can be integrated over

an energy range of width beyond an ionization edge. For a very thin specimen

(negligible plural scattering) the integrated intensity is

I

1

k

(β, ) = NI

0

σ

k

(β, ) (3.156)

where the “partial” cross section σ

k

(β, ) is defined by

σ

k

(β, ) =

E

k

+

E

k

dσ

dE

dE (3.157)

For numerical integration of dσ/dE, use can be made of the power-law behavior,

Eq. (3.154), to reduce the required number of energy increments.

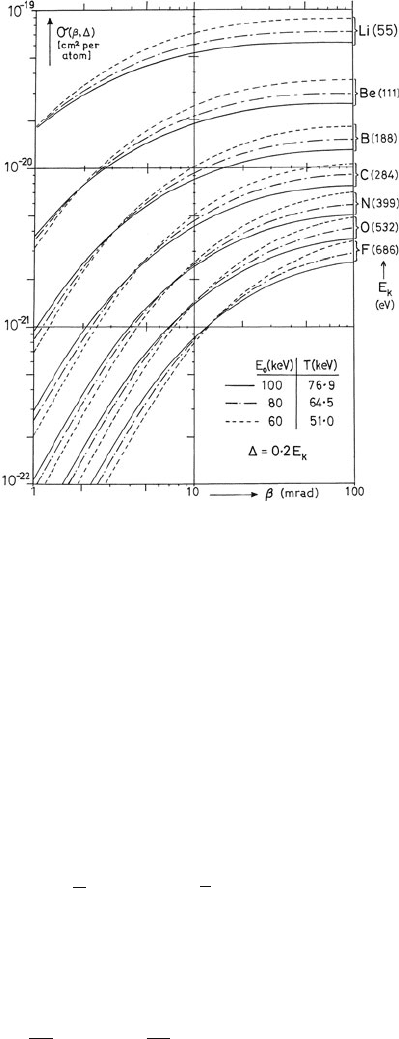

Figure 3.41 shows the calculated angular dependence of K-shell partial cross

sections for first-row (second-period) elements. The cross sections saturate at large

values of β (i.e., above the Bethe ridge angle θ

r

) due to the fall in df/dE outside the

dipole region. The median scattering angle (for energy losses in the range E

k

to E

k

+

), corresponding to a partial cross section equal to one half the saturation value,

is typically 5

¯

θ

E

, where

¯

θ

E

= (E

k

+ /2)/(2γ T). Figure 3.41 shows that whereas

the saturation values decrease with increasing incident energy, the low-angle cross

sections increase. This behavior results from the fact that the angular distribution

becomes more sharply peaked about θ = 0 as the incident energy increases, so a

small collection aperture accepts a greater fraction of the scattering.

196 3 Physics of Electron Scattering

Fig. 3.41 Partial cross

section for K-shell ionization

of second-period elements,

calculated assuming

hydrogenic wavefunctions

and relativistic kinematics for

an integration window

equal to one-fifth of the edge

energy. From Egerton (1979),

copyright Elsevier

3.6.3.2 Integral and Total Cross Sections

For a very large integration range , the partial cross section becomes equivalent to

the “integral” cross section σ

k

(β) for inner-shell scattering into angles up to β and

all possible values of energy loss. This cross section can be evaluated by choosing

the upper limit of integration in Eq. (3.157) so that contributions from higher energy

losses are negligible. For small β, taking an upper limit equal to 3E

k

gives less than

1% error due to higher losses, but for large β the limit must be set higher because

of contributions from the Bethe ridge.

For β less than the Bethe ridge angle θ

r

≈ (2θ

E

)

1/2

, the integral cross section can

be predicted with moderate accuracy (Egerton, 1979) by using a formula analogous

to Eq. (3.149):

σ

k

(β) 4πa

2

0

(R/T)(R/E)f

k

ln

1 +(β/θ

E

)

2

(3.158)

where the mean energy loss

¯

E is defined by

¯

E =

E

0

0

E

dσ

dE

dE

E

0

0

dσ

dE

dE (3.159)

3.7 The Form of Inner-Shell Edges 197

and

¯

θ

E

= E/2γ T. Typically E ≈ 1.5E

k

and the quantity f

k

in Eq. (3.158)isthe

dipole oscillator strength, which for K-shell ionization is approximately 2.1 − Z/27.

By setting β = π , the integral cross section becomes equal to the total cross

section σ

k

for inelastic scattering from shell k. An approximate expression for σ

k

is

the “Bethe asymptotic cross section” (Bethe, 1930):

σ

k

≈ 4πa

2

0

N

k

b

k

(R/T)(R/E

k

)ln(c

k

T/E

k

) (3.160)

where N

k

is the number of electrons in shell k (2, 8, and 18 for K-, L-, and M-

shells), while b

k

(≈ f

k

/N

k

) and c

k

(≈ 4E

k

/E) are factors that can be obtained by

calculation or from measurements of cross section (Inokuti, 1971; Powell, 1976).

If experimental values are available for different incident energies, a plot of Tσ

k

against ln T (known as a Fano plot) should yield a straight line, according to Eq.

(3.160). Linearity of the Fano plot is sometimes used as a test of the reliability of

the measured cross sections or of the applicability of Bethe theory (for example,

at low incident energies). The slope and intercept of the plot give the values of b

k

and c

k

. At incident electron energies above about 200 keV, Bethe theory must be

modified to take account of retardation effects and a modified form of the Fano plot

is required (Appendix A).

3.7 The Form of Inner-Shell Edges

In this section, we consider first the overall shape of ionization edges, as deduced

from atomic calculations (Leapman et al., 1980; Rez, 1982), photoabsorption data

(Hubbell, 1971; Veigele, 1973), and libraries of EELS data (Zaluzec, 1981; Ahn and

Krivanek, 1983; Ahn, 2004). We concentrate on edges within the energy range 50–

2000 eV, which are more easily observable by EELS. A table of edge shapes and

edge energies is given in Appendix D, together with a table showing the relation-

ship between the quantum-mechanical and spectroscopy notations for inner-shell

excitation.

3.7.1 Basic Edge Shapes

Because the wavefunctions of core electrons change relatively little when atoms

aggregate t o form a solid, an atomic model provides a useful indication of the gen-

eral shape of inner-shell edges. Following Manson (1972), Leapman et al. (1980)

calculated differential cross sections for K-, L-, and M-shell ionization on the basis

of the Hartree–Slater central-field model (Section 3.6.1). Their results for K-shell

edges are shown in Fig. 3.42a, where the vertical axis represents the core-loss

intensity after background subtraction and in the absence of plural scattering and

instrumental broadening. Although the vertical scale in Fig. 3.42 refers to an inci-

dent energy of 80 keV and a collection semi-angle β of 3 mrad, the K-edges retain

their characteristic “sawtooth” shape for different values of E

0

and β; see Fig. 3.42b.