Egerton R.F. Electron Energy-Loss Spectroscopy in the Electron Microscope

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

208 3 Physics of Electron Scattering

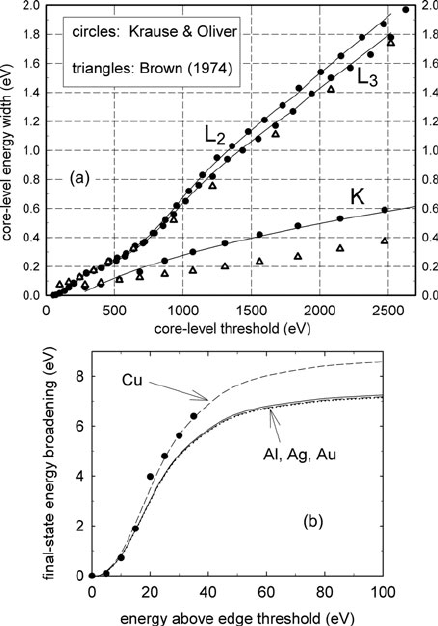

Fig. 3.51 (a)Energy

broadening

i

of core levels,

according to Krause and

Oliver (1979)andBrown

(1974); the solid lines

represent parameterized

formulas (Egerton, 2007).

(b) Final-state energy

broadening as a function of

energy above threshold,

calculated from Eq. (3.163)

with m = m

0

. The data points

represent measurements on

aluminum by Hébert (2007)

(mainly Auger emission in light elements) and the value of

i

depends mainly

on the threshold energy of the edge; see Fig. 3.51a.

Further spectral broadening occurs because of the limited lifetime τ

f

of the final

state. Transition to a final-state energy ε above the ionization threshold results in an

electron (effective mass m) moving away from the atom with speed v and kinetic

energy ε = mv

2

/2. This energy is lost within a lifetime of approximately λ

i

/v,the

inelastic mean free path λ

i

being limited to a few nanometers for ε<50 eV (see

later, Fig. 3.57). The resulting energy broadening is therefore

f

≈ /τ

f

≈ v/λ

i

= (/λ

i

)(2ε/m)

1/2

(3.163)

Based on photoelectron spectroscopy, Seah and Dench (1979) parameterized the

inelastic mean free path (for 1 eV <ε<10

4

eV) in the form

λ

i

(nm) = 538aε

−2

+0.41a

3/2

ε

1/2

(3.163a)

3.8 Near-Edge Fine Structure (ELNES) 209

where ε is in eV and a is the atomic diameter; a

3

= A/(602ρ), with A = atomic

weight and ρ = specimen density in g/cm

3

. According to Eqs. (3.163) and (3.163a),

f

increases with excitation energy above the threshold and the observed DOS struc-

ture is progressively damped with increasing energy loss. For ε>60 eV, the ε

1/2

term in Eq. (3.163a) dominates and

f

tends to a limit (0.93 eV)a

–3/2

, between 7

and 9 eV for simple metals; see Fig. 3.51b.

The measured ELNES is also broadened by the instrumental energy resolution

E. To allow for this broadening and that due to the initial-state width, calculated

densities of states can be convolved with a Gaussian or Lorentzian function of width

(

i

2

+E)

1/2

. In the case of L

23

or M

45

edges, spin–orbit splitting results in two

initial states with different energy (Fig. 3.45) and the measured ELNES therefore

consists of two shifted DOS distributions. This effect can be removed by Fourier

ratio deconvolution, with the low-loss region replaced by two delta functions whose

strengths are suitably adjusted (Leapman et al., 1982).

Band structure calculations that predict the electrical properties of a solid give

the total densities of states and provide only approximate correlation with measured

ELNES. For a more accurate description, the DOS must be resolved into the cor-

rect angular momentum component at the appropriate atomic site. Pseudopotential

methods have been adapted to this requirement and were used to calculate ELNES

for diamond, SiC, and Be

2

C (Weng et al., 1989). The augmented plane wave (APW)

method has provided realistic near-edge structures of transition metal compounds

(Muller et al., 1982; Blaha and Schwarz, 1983). Some of the options are described

in a review paper by Mizoguchi et al. (2010). The Wien2k program for perform-

ing band structure calculations based on density functional theory is described by

Hébert (2007); see also Section 4.7.2.

3.8.1.1 Nondipole Effects

As indicated by Eq. (3.162), energy-loss fine structure represents the density of final

states modulated by an atomic transition matrix. If the initial state is a closed shell,

the many-electron matrix element of Eq. (3.23) can be replaced by a single-electron

matrix element, defined by

M(q, E) =

ψ

∗

f

exp(i q ·r)ψ

i

dτ (3.164)

where ψ

i

and ψ

f

are the initial- and final-state single-electron wavefunctions and

the integration is over all volume τ surrounding the initial state. Expanding the

operator as

exp(i q ·r) = 1 +i(q ·r) +higher order terms (3.164a)

210 3 Physics of Electron Scattering

enables the integral in Eq. (3.164) to be split into components. The first of these,

arising from the unity term in Eq. (3.164a), is zero because ψ

i

and ψ

f

are orthogo-

nal wavefunctions. The second integral containing (q·r)iszeroif ψ

i

and ψ

f

have the

same symmetry about the center of the excited atom (r = 0) such that their product

is even; q · r itselfisanodd function and the two halves of the integral then can-

cel. But if ψ

i

is an s-state (even symmetry) and ψ

f

is a p-state (odd symmetry), the

integral is nonzero and transitions are observed. This is the basis of the dipole selec-

tion rule, according to which the observed N(E) is a symmetry-projected density of

states.

For the dipole rule to hold, the higher order terms in Eq. (3.163)mustbe

negligible; if not, a third integral (representing dipole-forbidden transitions) will

modify the energy dependence of the fine structure. From the above argument, the

dipole condition is defined by the requirement q · r 1 for all r, equivalent to

q q

d

= 1/r

c

, where r

c

is the radius of the core state (defining the spatial region

in which most of the transitions occur). The hydrogenic model gives r

d

≈ a

0

/Z

∗

,

where Z

∗

is the effective nuclear charge.

For K-shells, Z

∗

≈ Z − 0.3 (see Section 3.6.1); for carbon K-shell excitation

by 100-keV electrons, dipole conditions should therefore prevail for θ θ

d

=

Z

∗

a

0

k

0

= 67 mrad, a condition fulfilled for most of the transitions since the median

angle of scattering is around 10 mrad (Fig. 3.41). In agreement with this esti-

mate, atomic calculations indicate that nondipole contributions are less than 10%

of the total for q < 45 nm

−1

, equivalent to θ < 23 mrad for 100-keV electrons

(Fig. 3.52a,b). A small spectrometer collection aperture (centered about the optic

axis) can therefore ensure that nondipole effects are minimized. Saldin and Yao

(1990) argue that dipole conditions hold only over an energy range ε

max

above the

excitation threshold, with ε

max

≈ 33 eV for Z = 3, increasing to 270 eV for Z =

8. Dipole conditions should therefore apply to the ELNES of elements heavier than

Li and to the EXELFS region for oxygen and heavier elements, for the incident

energies used in transmission spectroscopy.

For L

23

edges, atomic calculations (Saldin and Ueda, 1992)giveq

d

a

0

≈ Z

∗

/9

with Z

∗

= Z − 4.5, so for silicon and 100-keV incident electrons θ

d

≈ 11 mrad.

Solid-state calculations for Si (Ma et al., 1990) have suggested that nondipole effects

are indeed small (within 5 eV of the threshold) for 12.5-mrad collection semi-angle

(Fig. 3.52c) but are substantial for a large collection aperture, where monopole

2p → 3p transitions make a substantial contribution (Fig. 3.53d). Monopole tran-

sitions have been observed at the Si–L

23

edge of certain minerals and have been

attributed to the low crystal symmetry that induces mixing of p- and d-orbitals

(Brydson et al., 1992a).

A high density of dipole-forbidden states just above the Fermi level may lead

to observable monopole peaks, but mainly in spectra recorded with a displaced

collection aperture where the momentum transfer is large (Auerhammer and Rez,

1989). The dipole approximation appears justified for all M-edges, at incident ener-

gies above 10 keV and with an axial collection aperture (Ueda and Saldin, 1992).

A further discussion of nondipole effects is given by Hébert (2007) and (for the

low-loss region) by Gloter et al. (2009).

3.8 Near-Edge Fine Structure (ELNES) 211

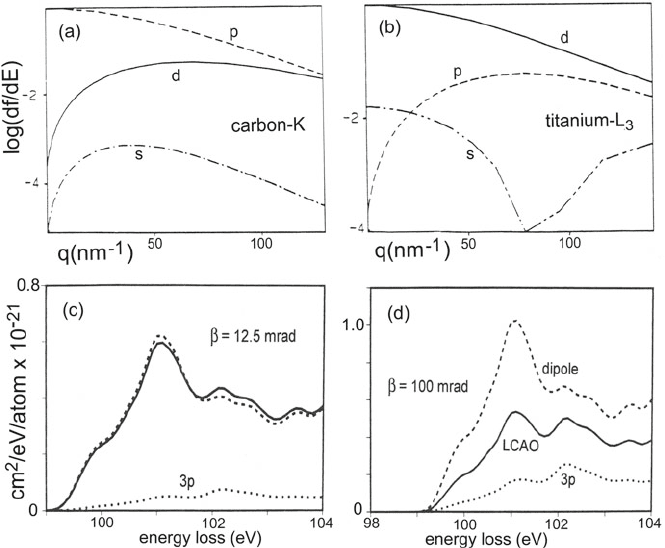

Fig. 3.52 Generalized oscillator strength (on a logarithmic scale) as a function of wave number

for transitions to s, p,andd final states 5 eV above the edge threshold, calculated for (a) carbon

K-edge (1s initial state) and (b) titanium L

3

edge (2p

3/2

initial state). From Rez (1989), copyright

Elsevier. (c, d) Silicon L

23

differential cross section for 100-keV incident electrons and acceptance

angles of 12.5 and 100 mrad. Solid lines are results of LCAO calculations, not using the dipole

approximation; dotted lines represent the contribution from 2p → 3p transitions. Dashed lines

represent the dipole approximation. Reprinted with permission from Ma et al. (1990), copyright

1990, American Institute of Physics

3.8.1.2 Core Hole Effects

After core electron excitation, an inner-shell vacancy (core hole) is left behind; see

Fig. 3.53b. Because the core hole perturbs the final state of the transition, one-

electron band structure theory is not an exact description of ELNES. Core hole

effects can be included within band structure calculations by using a supercell

method (Mizoguchi et al., 2010). Band structure calculations assume periodicity,

whereas the core hole occurs only once, so it is necessary to use a supercell much

larger than the unit cell of the crystal being simulated. For the Mg K-edge in MgO,

Mizoguchi et al. (2010) found that a 54-atom supercell was necessary to avoid

artifacts; see Fig. 3.53f.

A two-particle approximation is to generalize the concept of density of states

N(E) to include temporary bound states formed by interaction between the excited

212 3 Physics of Electron Scattering

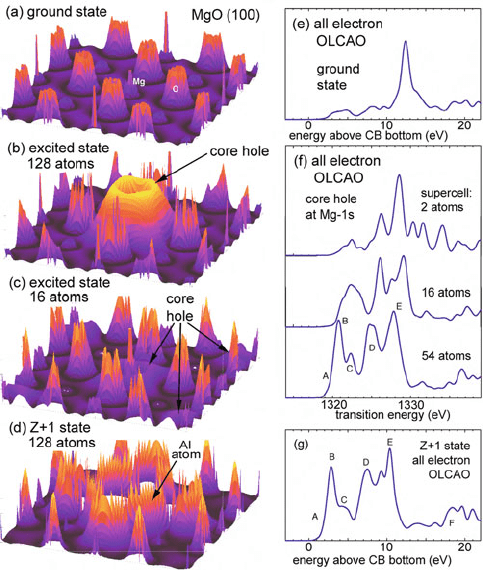

Fig. 3.53 (a)–(d) Square of the wavefunction for an e lectron at the bottom of the MgO conduction

band, in the ground state, in an excited state with a core hole at the Mg 1s site, and in the Z+1

approximation (Mg replaced by an Al atom). (e)–(g)MgK-edge ELNES calculated using the

all-electron OLCAO method, without and with a core hole, and using the Z+1 procedure. From

Mizoguchi et al. (2010), copyright Elsevier

core electron and the core hole: core excitons. Since their effective radius may be

larger or smaller than atomic dimensions, they are analogous to the Wannier or

Frenkel excitons observed in the low-loss region of the spectrum (Section 3.3.3).

The exciton energies can be estimated by use of the Z + 1 or optical-alchemy

approximation (Hjalmarson et al., 1980; Elsässer and Köstlmeier, 2001) in which

the potential used in DOS or MS calculations is that of the next-highest atom in

the periodic table. This is equivalent to assuming that the core hole increases (by

one unit) the effective charge seen by outer electrons. Although not equivalent to a

multi-particle calculation, the Z+1 approximation often gives an improvement over

a ground-state calculation; see Fig. 3.52e–g.

In an insulator, core-exciton levels lie within the energy gap between valence

and conduction bands and may give rise to one or more peaks below the threshold

for ionization to extended states (Pantelides, 1975). Such peaks can be identified

as excitonic if band structure calculations are available on an absolute energy scale

3.8 Near-Edge Fine Structure (ELNES) 213

and if the energy-loss axis has been accurately calibrated (Grunes et al., 1982). Even

when peaks are not visible, excitonic effects may sharpen the ionization threshold,

modify the fine structure, or shift the threshold to lower energy loss, as proposed for

graphite (Mele and Ritsko, 1979) and boron nitride (Leapman et al., 1983). These

effects may be somewhat different in EELS, as compared to x-ray absorption spec-

troscopy, if the excited atom relaxes before the fast electron exits the exciton radius

(Batson and Bruley, 1991; Batson, 1993b).

In ionic compounds, the exciton is more strongly bound at the cation than at the

anion site (Pantelides, 1975; Hjalmarson, 1980), introducing further differences in

near-edge structure at the respective ionization edges. In the case of a metal, the

effect of the core hole is screened within a short distance (≈0.1 nm), but electron–

hole interaction may still modify the shape of an ionization edge: if the initial state

is s-like, the edge may become more rounded; if p-like, it may be sharpened slightly

(Mahan, 1975).

To properly describe the white line features present in L

23

edges of transition

metals and M

45

edges of the lanthanides, a relativistic many-particle calculation is

required, including electron–electron and electron–hole interactions (Ikeno et al.,

2006). A more empirical procedure is based on fitting parameters (de Groot and

Kotani, 2008).

3.8.2 Multiple-Scattering Interpretation

An alternative approach to understanding ELNES makes use of concepts first devel-

oped to explain x-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES, also referred to as

NEXAFS). This is an extension of EXAFS theory, taking into account multiple

(plural) elastic scattering of the ejected core electron. Multiple scattering is impor-

tant in the near-edge region, where backscattering occurs in a larger volume of the

specimen as a result of the long inelastic mean free path of the low-energy ejected

electron (page 219). Even so, the r esults reflect the local environment of the excited

atom. This environment is divided into concentric shells surrounding the excited

atom and backscattering from these shells is calculated sequentially. Documented

programs for performing such calculations are available (Durham et al., 1982;

Vvedensky et al., 1986; Ankudinov et al., 1998). Usually a moderate number of

coordination shells is sufficient to achieve convergence; see Fig. 3.54. The backscat-

tering itself occurs within a diameter of several nanometers but electron waves

scattered from more distant shells have almost random phase and their contribu-

tions tend to cancel, so the ELNES modulations represent information mostly from

1 nm of the excited atom (Wang et al., 2008a).

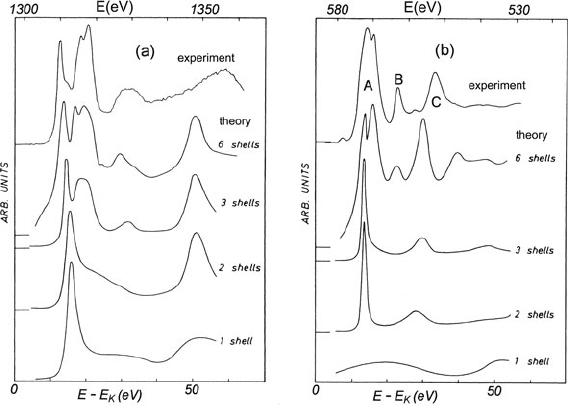

In the case of MgO, the Mg cations scatter weakly and do not contribute appre-

ciably to the fine structure. The peak labeled C in Fig. 3.54b arises from single

scattering from oxygen nearest neighbors and therefore appears when only two

shells are used in the calculations. Peak B represents single scattering from second-

nearest oxygen atoms and emerges when four shells are included. Peak A is believed

214 3 Physics of Electron Scattering

Fig. 3.54 Multiple scattering simulation of the fine structure of (a) magnesium K-edge and

(b) oxygen K-edge of MgO, shown as a function of the number of shells used in the calculation.

Spectra at the top represent EELS measurements with background subtracted and plural scatter-

ing removed by deconvolution. From Lindner et al. (1986), copyright American Physical Society.

Available at http://link.aps.org/abstract/PRB/v33/p22

to arise from plural scattering among oxygen nearest neighbors (Rez et al., 1995).

Comparison of the L-edges of MgO and Mg(OH)

2

has shown that the differences

are mainly due to atoms in the second and third shells, showing that medium-range

structure can be important and amenable to ELNES analysis (Jiang et al., 2008).

In the transition metal oxides, backscattering from nearest-neighbor oxygen atoms

gives rise to a prominent peak about 40 eV from the metal-L

23

edge, providing a

convenient test for oxidation (Wang et al., 2006).

An effect found to be important for higher order shells is focusing of the ejected-

electron wave by intermediate shells, in situations where atoms are radially aligned

(Lee and Pendry, 1975). A related effect arises from the centrifugal barrier created

by first-neighbor atoms, which acts on high angular momentum components of the

emitted wave, confining it locally for energies just above the edge threshold. This

shape-resonance effect has been used to interpret absorption spectra of diatomic

gases (Dehmer and Dill, 1977) and transition metal complexes (Kutzler et al., 1980).

The resonance value of the ejected-electron wave number k obeys the relationship

kR = constant, where R is the bond length (Bianconi, 1983; Bianconi et al., 1983a),

resulting in the resonance energy (above threshold) being proportional to 1/R

2

.A

similar behavior is apparent from band structure calculations of transition metal

elements (Muller et al., 1982): for metals having the same crystal structure, the

energies of DOS peaks are proportional to 1/a

2

, where a is the lattice constant.

3.8 Near-Edge Fine Structure (ELNES) 215

Although formally equivalent to a densities-of-states interpretation of ELNES

(Colliex et al., 1985), multiple scattering (MS) calculations are performed in real

space. It is t herefore possible to treat disordered systems or complicated molecules

such as hemoglobin (Durham, 1983) and calcium-containing proteins (Bianconi

et al., 1983b) for which band structure calculations would not be feasible.

3.8.3 Molecular-Orbital Theory

In many covalent materials, a useful explanation of ELNES is in terms of molecular

orbital (MO) theory (Glen and Dodd, 1968): the local band structure is approxi-

mated as a linear combination of atomic orbitals (LCAO) of the excited atom and

its immediate neighbors. A simple example is graphite, in which the four valence

electrons of each carbon atom are sp

2

hybridized, resulting in three strong σ bonds

to nearest neighbors within each atomic layer; the remaining p-electron contributes

to a delocalized π orbital. The corresponding antibonding orbitals are denoted as σ

∗

and π

∗

; they are the empty states into which core electrons can be excited, giving

rise to distinct peaks in the K-edge spectrum (see Fig. 5.37).

In organic compounds, the presence of delocalized or unsaturated bonding again

gives rise to sharp π

∗

peaks at an edge threshold. For molecules containing car-

bon atoms with different effective charge, such as the nucleic acid bases, s everal

peaks are observable and have been interpreted in terms of chemical shifts (Isaacson,

1972a, b). Molecular-orbital concepts have been useful in the interpretation of the

fine structure of edges recorded from minerals (Krishnan, 1990; McComb et al.,

1992) and provide at least a qualitative understanding of ionization edges recorded

from TiO

2

(Radtke and Botton, 2011). Computer programs for MO calculations are

freely available.

6

3.8.4 Multiplet and Crystal-Field Effects

The core hole created by inner-shell ionization has an angular momentum that can

couple with the net angular momentum of any partially filled shells within the

excited atom. Such coupling is strongest when the hole is created within the par-

tially filled shell itself, as in the case of N

45

ionization of sixth-period elements

from Cs (Z = 55) to Tm (Z = 69). Both spin and orbital momentum are involved,

leading to an elaborate fine structure (Sugar, 1972). A similar effect is observed in

the M-shell excitation of third-period elements (Davis and Feldkamp, 1976). Where

the core hole is created in a complete shell, separate peaks may not be resolved but

the coupling can lead to additional broadening of the fine structure.

In lanthanide compounds, the 4f states are screened by 5s and 5p electrons and the

M

45

multiplet structure is largely an atomic effect. In t ransition metal compounds,

6

http://www.chem.ucalgary.ca/SHMO/, http://www.unb.ca/fredericton/science/chem/ajit/hmo.htm

216 3 Physics of Electron Scattering

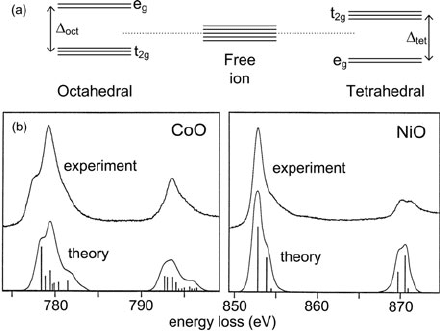

Fig. 3.55 (a) Crystal-field splitting of transition metal d-states, dependent on the symmetry of

the surrounding anions. (b) Multiplet structure of the L

3

and L

2

white lines of CoO and NiO, as

measured by EELS and as calculated by Yamaguchi et al. (1982). The vertical bars represent the

relative intensities of the calculated states, from which the smooth curves were derived by con-

volution with an instrumental resolution function. From Krivanek and Paterson (1990), copyright

Elsevier

however, the 3d states of the metal are sensitive to the chemical environment (e.g.,

the electrostatic field of the surrounding ligand anions such as oxygen). The d

xy

,

d

xz

, and d

yz

orbitals point at 45

◦

to the crystal (x,y,z) axes whereas the two other

d-orbitals lie along the axes; therefore, the degenerate d-states split into t

2g

and

e

g

levels separated by a crystal-field s plitting parameter that depends on the

coordination (point-group symmetry) of the anions; see Fig. 3.55a. This effect is

observable as a splitting of both the L

3

and the L

2

white-line peaks in transition

metal oxides; see Fig. 3.55b.

Similar crystal-field splittings are observed by photoelectron spectroscopy

(Novakov and Hollander, 1968) and by x-ray absorption spectroscopy. The multiplet

structure can be calculated for different values of the crystal-field parameter (de

Groot et al., 1990), so comparison with experiment can provide information about

the character of the bonding in minerals (Garvie et al., 1994). The availability of

monochromated TEMs makes multiplet splitting more easily observable by EELS,

at least for edges where the initial-state (lifetime) broadening is not excessive (Lazar

et al., 2003; Kothleitner and Hofer, 2003).

3.9 Extended Energy-Loss Fine Structure (EXELFS)

Although the ionization-edge fine structure decreases in amplitude with increas-

ing energy loss, oscillations of intensity are detectable over a range of several

hundred electron volts if no other ionization edges follow within this region. This

3.9 Extended Energy-Loss Fine Structure (EXELFS) 217

extended fine structure was first observed in x-ray absorption spectra (as EXAFS)

and interpreted as a densities-of-states effect, involving diffraction of the ejected

core electron due to the long-range order of the solid. However, quite strong EXAFS

modulations are obtained from amorphous samples and the effect is now recog-

nized to be a measure of the short-range order, involving mainly scattering from

nearest-neighbor atoms.

If released with a kinetic energy of 50 eV or more, the ejected core electron

behaves much like a free electron, the densities of states N(E)inEq.(3.162) approx-

imating a smooth function proportional to (E −E

k

)

1/2

(Stern, 1974). Nevertheless,

weak oscillations in J

1

k

(E) can arise from interference between the outgoing spher-

ical wave (representing the ejected electron) and reflected waves that arise from

elastic backscattering of the electron from neighboring atoms; see Fig. 3.56.This

interference perturbs the final-state wavefunction in the core region of the central

atom and therefore modulates N(E). The interference can be constructive or destruc-

tive, depending on the return path length 2r

j

(where r

j

is the radial distance to the jth

shell of backscattering atoms) and the wavelength λ of the ejected electron. Since

the velocity of the ejected electron is low compared to the speed of light, the wave

number k of the ejected electron is given by classical mechanics:

k = 2π/λ ≈

[

2m

0

(E − E

k

)

]

1/2

/ (3.165)

where E is the energy transfer (from an incident electron or x-ray photon) and E

k

is

the threshold energy of the edge. With increasing energy loss E, the interference is

therefore alternately constructive and destructive, giving maxima and minima in the

intensity of the scattered primary electrons.

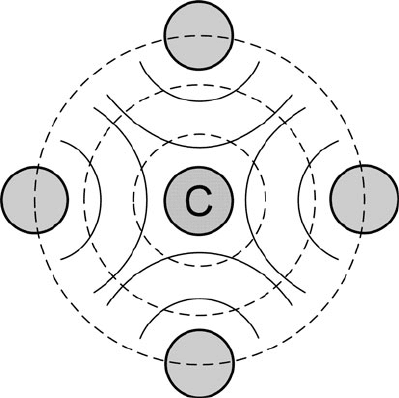

Fig. 3.56 Pictorial

representation of the electron

interference that gives rise to

oscillations of fine structure

in a c ore-loss or x-ray

absorption spectrum.

Wavefronts of the outgoing

wave, representing a core

electron ejected from the

central atom C, are shown as

dashed circles.Thesolid arcs

depict waves backscattered

from nearest-neighbor atoms