Egerton R.F. Electron Energy-Loss Spectroscopy in the Electron Microscope

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

148 3 Physics of Electron Scattering

3.3.2.2 The Effect of Band Structure

The free-electron plasmon model is often a good approximation (Figs. 3.12 and

3.16), but in most materials the lattice has a significant effect on electron motion,

as reflected in the band structure of the solid and the nonspherical form of the

Fermi surface. Single-electron transitions can then occur outside the shaded region

of Fig. 3.17, for example, at low q, the necessary momentum being supplied by the

lattice.

The transition rate is determined by details of the band structure. Where the

single-electron component in a l oss spectrum is high (e.g., transition metals) the

E-dependence may exhibit a characteristic fine structure. In semiconductors and

insulators, this structure reflects a joint density of states (JDOS) between the valence

and conduction bands. Peaks in the JDOS occur where branches representing the

initial and final states on the energy–momentum diagram are approximately parallel

(Bell and Liang, 1976).

3.3.2.3 Damping of Plasma Oscillations

As remarked in Section 3.3.1, plasma resonance in solids i s highly damped and

the main cause of this damping is believed to be the transfer of energy to single-

electron transitions (creation of electron–hole pairs). On a free-electron model, such

coupling s atisfies the requirements of energy and momentum conservation only if

the magnitude of the plasmon wavevector q exceeds the critical value q

c

. In a real

solid, however, momentum can be supplied by the lattice (in units of a reciprocal

lattice vector, i.e., an Umklapp process) or by phonons, enabling the energy transfer

to occur at lower values of q, as indicated schematically by the horizontal arrow in

Fig. 3.17. The energy of a resulting electron–hole pair is eventually released as heat

(phonon production) or electromagnetic radiation (cathodoluminescence).

In fine-grained polycrystalline materials, grain boundaries may act as an addi-

tional source of damping for low-q (long-wavelength) plasmons, resulting in a

broadening of the energy-loss peak at small scattering angles (Festenberg, 1967).

As the diameter d of silicon spheres decreased from 20 to 3.5 nm, Mitome et al.

(1992) observed a similar increase in width, presumably due to increased damping

by the surfaces. They also reported an increase in plasmon energy (from 16.7 to

17.5 eV) proportional to 1/d

2

. The authors argue that dispersion (plasmon wave-

length constrained to be less than the particle diameter) would cause an increase of

only 0.1 eV and that their measurements indicate a quantum size effect.

3.3.2.4 Shift of Plasmon Peaks

Single-electron and plasmon processes are also linked in the sense that the

intensity observed in the energy-loss spectrum is not simply a sum of two inde-

pendent processes. Susceptibility χ is the additive quantity, not the energy-loss

function.

3.3 Excitation of Outer-Shell Electrons 149

Drude theory can be extended to the case of electrons that are bound to the ion lat-

tice with a natural frequency of oscillation ω

b

, the equation of motion in an external

field E becoming

m

¨

x +m

˙

x +mω

2

b

x =−eE (3.63)

The solution is now x = (−eE/m)(ω

2

+i −ω

b

2

)

−1

and if n is the electron density,

the polarization has an amplitude P = ε

0

χ

b

E = enx,giving

ε = 1 +χ

b

= 1 +

ω

2

p

ω

2

b

−ω

2

−iω

(3.64)

where ω

p

= [ne

2

/(m ε

0

)]

1/2

would be the plasma resonance frequency if the elec-

trons were free, whereas in fact the resonance peak is shifted to an angular frequency

(ω

2

p

+ω

2

b

)

1/2

. This situation applies to the valence electrons in a semiconductor or

insulator, where the binding energy ω

b

is comparable with the energy gap E

g

.The

energy E

b

p

of the resonance maximum is given by

(E

b

p

)

2

≈ E

2

p

+E

2

g

(3.65)

For most practical cases E

2

g

<<E

2

p

, which may explain why the valence-resonance

peak of semiconductors (and even insulators) is given fairly well by the free-electron

formula; see Table 3.3. The extended Drude model provides a fair approximation to

the energy-loss function of insulators such as alumina, although the behavior of the

real and imaginary parts of the permittivity is less well represented (Egerton, 2009).

If there are n

f

free electrons and n

b

bound electrons per unit volume, ε = 1 +

χ

f

+ χ

b

, where χ

f

is given by Eq. (3.39a) with n = n

f

and χ

b

by Eq. (3.64). The

resonance energy E

b

p

is then given (Raether, 1980)by

(E

b

p

)

2

≈

E

2

p

[1 +χ

b

(ω

p

)]

(3.66)

Table 3.3 Experimental energy E

p

(expt) of the main peak in the energy-loss spectra of several

semiconductors and insulators, compared with the plasmon-resonance energy E

p

(calc) given by

Eq. (3.41), where n is the number of outer-shell (valence) electrons per unit volume. Values in eV,

from Raether (1980)

Material E

p

(expt) E

p

(calc)

Diamond 34 31

Si 16.5 16.6

Ge 16.0 15.6

InSb 12.9 12.7

GaAs 15.8 15.7

NaCl 15.5 15.7

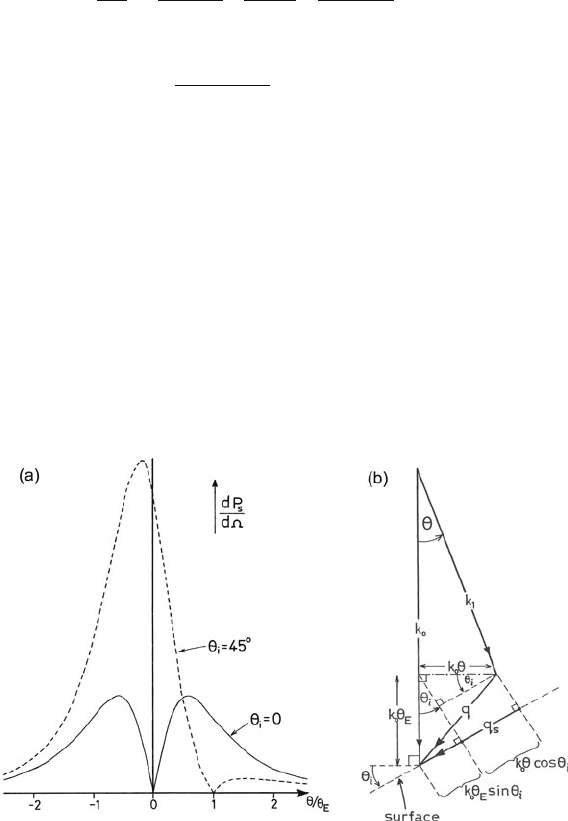

150 3 Physics of Electron Scattering

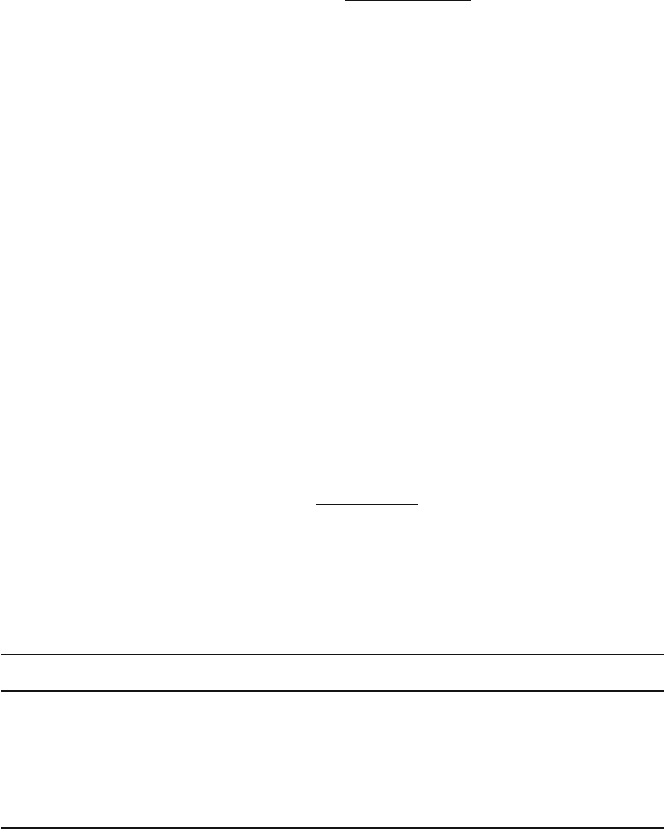

Fig. 3.18 (a) Dielectric properties of a free-electron gas with E

p

= 16 eV and E

p

= 4eV.

(b) Drude model with interband transitions added at E

b

= 10 eV (Daniels et al., 1970)

and can be raised or lowered, depending on the sign of χ . If interband transitions

take place at an energy that is higher than E

p

,Eq.(3.64) indicates that χ

b

(E

p

)is

positive. Polarization of the bound electrons reduces the restoring force on the dis-

placed free electrons, reducing the resonance energy below the free-electron value.

Conversely, if interband transitions occur at a lower energy, the plasmon peak is

shifted to higher energy, as in Fig. 3.18.

In a semiconductor, n

f

corresponds to a relatively low density of conduction

electrons. Even for n

f

∼ 10

19

cm

−3

, the corresponding resonance corresponds to

ω

f

≈ 0.25 eV, too small to be easily observable by EELS, and with negligible

influence on the resonance of the valence electrons. At high doping levels, however,

the electron concentration in an n-type semiconductor may become high enough to

give a second plasma resonance peak that is detectable in a high-resolution TEM-

EELS system. A 1.8-eV peak in the spectrum of LaB

6

has been attributed to this

cause, the valence-electron resonance being at 19 eV (Sato et al., 2008a). Graphite

and graphitic nanotubes can be doped with metals to introduce conduction electrons,

3.3 Excitation of Outer-Shell Electrons 151

resulting in a plasmon peak below 2 eV, in addition to the π-resonance peak around

6eVandthe(π +σ ) resonance around 27 eV (Liu et al., 2003).

In the case of a metal, interband transitions can cause a second resonance if the

value of n

b

is sufficiently large. For energies just below E

b

, ε

1

(E) is forced posi-

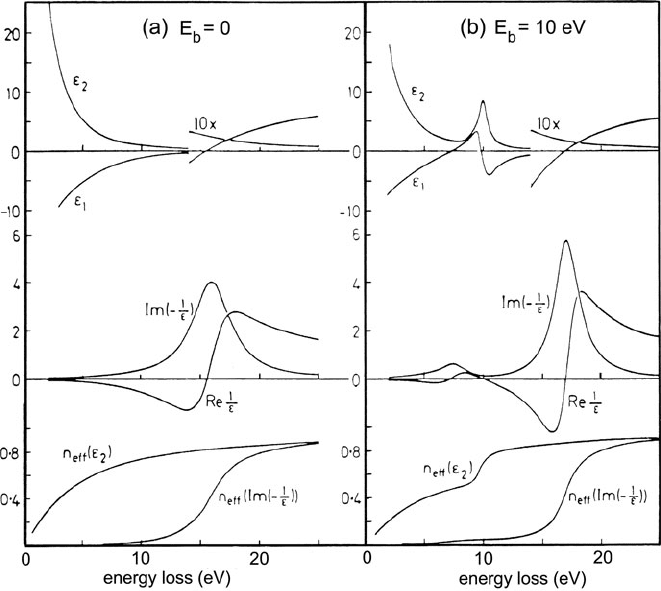

tive (see Fig. 3.18) and therefore crosses zero with positive slope (a condition for

a plasma resonance) at two different energies. Such behavior is observed in silver,

resulting in a (highly damped) resonance at 3.8 eV as well as the “free-electron”

resonance at 6.5 eV (see Fig. 3.19). In the case of copper and gold, interband tran-

sitions lead to a similar fluctuation in ε

1

(Fig. 3.19), but they occur at too low an

energy to cause ε

1

to cross zero and there is only one resonance point, at 5 eV in

gold.

The Drude model is used in connection with electrical conduction in metals, the

dc conductivity being given by

σ (0) = ε

0

τ

p

2

= τ n

f

e

2

/m

0

(3.66a)

Fig. 3.19 Energy-loss function Im(–1/ε) and real part ε

1

of the dielectric function, derived from

energy-loss spectroscopy of polycrystalline films of silver, gold, and copper. From Daniels et al.

(1970), copyright Springer

152 3 Physics of Electron Scattering

Here

p

is a plasmon frequency related to the quasi-free electrons (density n

f

)

that can undergo intraband transitions within the conduction band, and therefore

contribute to conductivity. In the case of aluminum,

p

≈ 12.5 eV, the intra-

band and interband contributions to the oscillator strength being n

f

= 1.9 and

n

b

= 1.2 electrons/atom, according to Smith and Segall (1986).

Layer crystals such as graphite and boron nitride have much weaker bonding

in the c-axis direction than within the basal (cleavage) plane. Each carbon atom

in graphite has one π-electron and three σ -electrons, the latter responsible for

the strong in-plane bonding. If isolated, these two groups of electrons might have

free-electron resonance energies of 12.6 and 22 eV, but coupling between the two

oscillating systems forces the resonance peaks apart; the observed peaks in the loss

spectrum occur at about 7 and 27 eV (Liang and Cundy, 1969).

In anisotropic materials the dielectric function ε(q, E) is actually a tensor ε

ij

and

the peak structure in the energy-loss spectrum depends on the direction of the scat-

tering vector q. For a uniaxial crystal such as graphite, axes can be chosen such that

off-diagonal components are zero, in which case ε( q, E) = ε

⊥

sin

2

+ ε

||

cos

2

,

where ε

⊥

= ε

11

= ε

22

and ε

||

= ε

33

are components of ε(E) perpendicular and

parallel to the c-axis; is the angle between q and the c-axis, which depends on the

scattering angle and the specimen orientation. If the c-axis is parallel to the incident

beam, the greatest contribution (for β>>θ

E

) comes from perpendicular excita-

tions and two plasmon peaks are observed. Under special conditions (e.g., small

collection angle β), the q||c excitations predominate and the higher energy peak is

displaced downward in energy. Further details about EELS of anisotropic materials

are given in Daniels et al. (1970) and Browning et al. (1991b).

3.3.3 Excitons

In insulators and semiconductors, it is possible to excite electrons from the valence

band to a Rydberg series of states lying just below the bottom of the conduction

band, resulting in an energy loss E

x

given by

E

x

= E

g

−E

b

/n

2

(3.67)

where E

g

is the energy gap, E

b

is the exciton binding energy, and n is an integer. The

resulting excitation can be regarded as an electron and a valence band hole, bound

to each other to form a quasiparticle known as the exciton.

Although the majority of cases fall between the two extremes, two basic types

can be distinguished. In the Wannier (or Mott) exciton, the electron–hole pair is

weakly bound (E

b

< 1 eV) and the radius of the “orbiting” electron is larger than

the interatomic spacing. The radius and binding energy can be estimated using a

hydrogenic formula: E

b

= e

2

/(8πεε

0

r) = m

0

e

4

/(8ε

2

ε

2

0

h

2

n

2

), where ε is the rel-

ative permittivity at the orbiting frequency (usually the light-optical value). The

electron and hole may travel together through the lattice with the absorbed momen-

tum q. Such excitons exist in high-permittivity semiconductors (e.g., Cu

2

O and

3.3 Excitation of Outer-Shell Electrons 153

CdS) but a high-resolution spectrometer system is needed to detect the associated

energy losses.

Frenkel excitons are strongly bound and relatively compact, the radius of the

electron orbit being less than the interatomic spacing. These are essentially excited

states of a single atom and in some solids may be mobile via a hopping mechanism.

For the alkali halides, where there is probably some Wannier and some Frenkel

character, the binding energy amounts to several electron volts, tending to be lower

on the anion site.

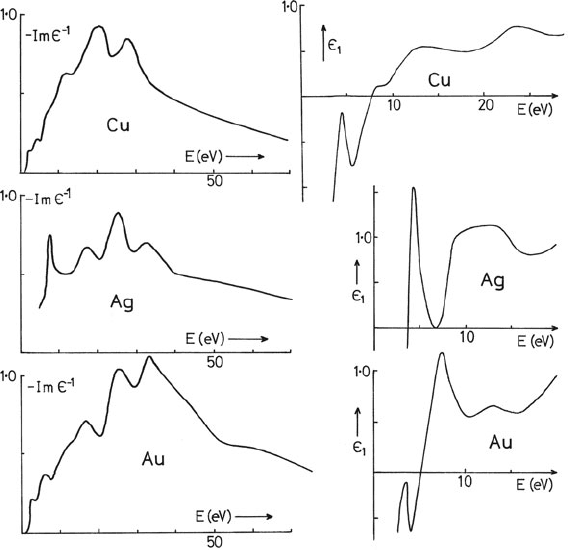

Energy-loss peaks due to transitions to exciton states are observed adjacent to

the “plasmon” resonance peak in alkali halides (Creuzburg, 1966; Daniels et al.,

1970), in rare gas solids (Daniels and Krüger, 1971), and in molecular crystals such

as anthracene. The peaks can be labeled according to the transition point in the

Brillouin zone and often show a doublet structure arising from spin–orbit splitting

(Fig. 3.20).

The energy E

x

of an exciton peak should obey a dispersion relation:

E

x

(q) = E

x

(0) +

2

q

2

/2m

∗

(3.68)

where m

∗

is the effective mass of the exciton. However, measurements on alkali

halides show dispersions of less than 1 eV (Creuzburg, 1966) suggesting that m

∗

m

0

(Raether, 1980).

Fig. 3.20 Energy-loss function for KBr, calculated from EELS measurements (full line) and from

optical data (broken line). The peak at about 13.5 eV is believed to represent a plasma resonance of

the valence electrons but the other peaks arise from excitons. From Daniels et al. (1970), copyright

Springer

154 3 Physics of Electron Scattering

3.3.4 Radiation Losses

If the velocity v of an electron exceeds (for a particular frequency) the speed of light

in the material through which it is moving, the electron loses energy by emitting

ˇ

Cerenkov radiation at that frequency. The photon velocity can be written as c/n =

c/

√

ε

1

, where n and ε

1

are the refractive index and relative permittivity, respectively,

of the medium, so the

ˇ

Cerenkov condition is satisfied when

ε

1

(E) > c

2

/v

2

(3.69)

In an insulator, ε

1

is positive at low photon energies and may considerably exceed

1. In diamond, for example, ε

1

> 6for3eV < E < 10 eV, so

ˇ

Cerenkov

radiation is generated by electrons whose incident energy is 50 keV or higher,

resulting in a “radiation peak” in the corresponding range of the energy-loss spec-

trum (see Fig. 3.21a). The photons are emitted in a hollow cone of semi-angle

φ = cos

−1

(cv

−1

ε

−1/2

1

) but are detected only if the specimen is tilted to avoid total

internal reflection.

Kröger (1968) developed relativistic formulas that include the retardation effects

responsible for

ˇ

Cerenkov emission. For relatively thick specimens, where internal

reflection of photons and surface plasmon excitation can be neglected, the double-

differential cross section becomes (Festenberg and Kröger, 1968)

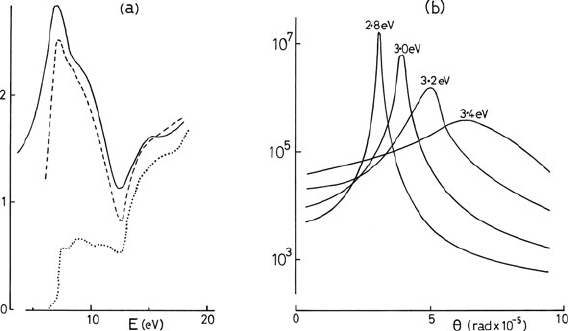

Fig. 3.21 (a) Solid line: low-loss spectrum of a 262-nm diamond sample, recorded using 55-keV

electrons (Festenberg, 1969). The dashed curve is the intensity derived from the relativistic theory

of Kröger (1968), while the dotted curve is calculated without taking into account retardation.

(b) Calculated angular dependence of the radiation-loss intensity for a 210-nm GaP specimen, 50-

keV incident electrons, and four values of energy loss. From Festenberg (1969), copyright Springer

3.3 Excitation of Outer-Shell Electrons 155

d

2

σ

d dE

=

Im(−1/ε)

π

2

a

0

m

0

v

2

n

a

θ

2

+θ

2

E

[(ε

1

v

2

/c

2

−1)

2

+ε

2

2

v

4

/c

4

]

[θ

2

−θ

2

E

(ε

1

v

2

/c

2

−1)]

2

+θ

4

E

ε

2

2

v

4

/c

4

(3.70)

The Lorentzian angular term of Eq. (3.32) is here replaced by a more compli-

cated function whose “resonance” denominator decreases to a small value (for

small ε

2

) at an angle θ

p

= θ

E

(ε

1

v

2

/c

2

−1)

1/2

. As a result, the angular distribu-

tion of inelastic scattering peaks sharply at small angles (<0.1 mrad). The calculated

peak position and width (as a function of energy loss; see Fig. 3.21b) are in broad

agreement with experiment (Chen et al., 1975) but for thin specimens a more com-

plicated formula, Eq. (3.84), must be used. Because the value of θ

p

is so small, the

radiation-loss electrons pass through an on-axis collection aperture of typical size

and can dominate the energy-loss spectrum at low energies, contributing additional

fine structure that interferes with bandgap measurements (Stöger-Pollach et al.,

2006).

Equation (3.70) shows that retardation effects cause the angular distribution to

depart from the Lorentzian form within the energy range for which ε

1

v

2

/c

2

> 0.5

(Festenberg and Kröger, 1968), a less restrictive condition than Eq. (3.69). This con-

dition is also fulfilled at relatively high energy loss (where ε

1

≈ 1 in both conductors

and insulators) if v

2

/c

2

exceeds approximately 0.5, leading again to deviation from

a Lorentzian angular distribution when the incident energy is greater than about

200 keV; see Appendix A.

Energy is also lost by radiation when an electron crosses a boundary where the

relative permittivity changes. This transition radiation results not from the change

of velocity but from change in the electric field strength surrounding the electron

(Frank, 1966; Garcia de Abajo, 2010). Polarized photons are emitted with energies

up to approximately 0.5 ω(1 −v

2

/c

2

)

−1/2

(Garibyan, 1960), but the probability

of this process appears to be of the order of 0.1%.

As a result of

ˇ

Cerenkov and transition losses, the electron energy-loss spectrum

below 5 eV (where nonretarded losses are small) can provide a direct measure of

the optical density of states (Garcia de Abajo et al., 2003). Although this connec-

tion may not hold at all planes in a structure (Hohenester et al., 2009), the EELS

measurement involves integration along the beam direction and good agreement

has been obtained between experimental results and calculated ODOS (Cha et al.,

2010). The advantage of using an electron beam over optical excitation is the possi-

bility of nanometer-scale resolution, which offers the option of examining repetitive

nanostructures of limited dimensions or those containing defects.

It is possible for an electron to gain energy at a surface illuminated by photons,

and electron energy-gain spectroscopy (EEGS) has been proposed as a method of

investigating nanostructures, combining high spatial and energy resolution (Garcia

de Abajo and Kociak, 2008). Energy gains of 200-keV electrons at the surface of

a carbon nanotube have been reported, together with the possibility of mapping

the electric field around nanostructures on a femtosecond timescale (Barwick et al.,

2009).

156 3 Physics of Electron Scattering

3.3.5 Surface Plasmons

Analogous to the bulk or volume plasmons that propagate inside a solid, there are

longitudinal waves of charge density that travel along an external surface or an

internal interface, namely, surface or interface plasmons. The electrostatic poten-

tial at a planar surface is of the form cos(qx −ωt)exp(−q|z|), where q and ω are the

wavevector and angular frequency of oscillation and t represents time. The surface

charge density is proportional to cos(qx−ωt)δ(z), and continuity of the electric field

leads to the requirement:

ε

a

(ω) + ε

b

(ω) = 0 (3.71)

where ε

a

and ε

b

are the relative permittivities on either side of the boundary.

Equation (3.71) defines the angular frequency ω

s

of the surface plasmon. Equation

(3.71) can be satisfied at the interface with a metal because the real part of the

permittivity becomes negative at low frequencies; see Fig. 3.19.

3.3.5.1 Free-Electron Approximation

The simplest situation corresponds to a single vacuum/metal interface where the

metal has negligible damping ( → 0). Then ε

a

= 1 and ε

b

≈ 1 −ω

2

p

/ω

2

, where

ω

p

= E

p

/ is the bulk plasmon frequency in the metal. Substitution into Eq. (3.71)

gives the energy E

s

of the surface plasmon peak in the energy-loss spectrum:

E

s

= ω

s

= ω

p

/

√

2 = E

p

/

√

2 (3.72)

A more general case is a dielectric/metal boundary where the permittivity of the

dielectric has a positive real part ε

1

and a much smaller imaginary part ε

2

for fre-

quencies close to ω

s

. Again assuming negligible damping in the metal, Eq. (3.72)

becomes

E

s

= E

p

/(1 +ε

1

)

1/2

(3.73)

and the energy width of the resonance peak is

E

s

= /τ = E

s

ε

2

(1 +ε

1

)

−3/2

(3.74)

Stern and Ferrell (1960) have calculated that a rather thin oxide coating (typically

4 nm) is sufficient to lower E

s

from E

p

/

√

2 to the value given by Eq. (3.74), and

experiments done under conditions of controlled oxidation support this conclusion

(Powell and Swan, 1960).

Equation (3.74) illustrates the fact that surface-loss peaks occur at a lower

energy loss than their volume counterparts, usually below 10 eV. In the case of

an interface between two metals, Eq. (3.71) leads to a surface plasmon energy

[(E

2

a

+E

2

b

)/2]

1/2

but in this situation, Jewsbury and Summerside (1980)have

argued that the excitation may not be confined to the boundary region.

3.3 Excitation of Outer-Shell Electrons 157

The intensity of surface plasmon scattering is characterized not by a differen-

tial cross section (per atom of the specimen) but by a differential “probability” of

scattering per unit solid angle, given for a free-electron metal (Stern and Ferrell,

1960)by

dP

s

d

=

πa

0

m

0

v

2

1 +ε

1

θθ

E

(θ

2

+θ

2

E

)

f (θ, θ

i

, ψ) (3.75)

f (θ, θ

i

, ψ) =

1 +(θ

E

/θ)

2

cos

2

θ

i

−(tan θ

i

cos ψ + θ

E

/θ)

2

1/2

(3.76)

where θ is the angle of scattering, θ

i

is the angle between the incident electron and

an axis perpendicular to the surface, and ψ is the angle between planes (perpendic-

ular to the surface) that contain the incident and scattered electron wavevectors. In

Eq. (3.76), θ and θ

i

can be positive or negative and θ

E

is equal to E

s

/γ m

0

v

2

.

The angular distribution of scattering is shown in Fig. 3.22. For normal incidence

(θ

i

= 0), f (θ , θ

i

, ψ) = 1 and (unlike the case of volume plasmons) the scattered

intensity is zero in the forward direction (θ = 0), a result of the fact that there is

then no component of momentum transfer along the boundary plane (momentum

perpendicular to the surface is absorbed by the lattice). The intensity rises rapidly to

a maximum at θ =±θ

E

/

√

3, so the minimum around θ = 0 is not easy to observe

with a typical TEM collection aperture and incident beam divergence.

Fig. 3.22 (a) Angular distribution of surface scattering; note the asymmetry and higher integrated

intensity of scattering in the case of a tilted (θ

i

= 45

◦

) specimen. (b) Vector diagram illustrating

the relationship between q and q

i

for the case where θ and θ

i

have the same sign and the scattering

angle is within the plane of incidence (ψ = 0)