Egerton R.F. Electron Energy-Loss Spectroscopy in the Electron Microscope

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

128 3 Physics of Electron Scattering

(Howie, 1995) because the energy losses involved are comparatively large. For

heavy elements, inner atomic shells make major contributions to both σ

i

and S.

3.2.2 Bethe Theory

In order to describe in more detail the inelastic scattering of electrons by an atom

(including the dependence of scattered intensity on energy loss), the behavior of

each atomic electron is specified in terms of transition from an initial state of wave-

function ψ

0

to a final state of wavefunction ψ

n

. Using the first Born approximation,

the differential cross section for the transition is (Inokuti, 1971)

dσ

n

d

=

m

0

2π

2

2

k

1

k

0

V(r)ψ

0

ψ

∗

n

exp(iq ·r) dτ

2

(3.20)

In Eq. (3.20), k

0

and k

1

are wavevectors of the fast electron before and after scat-

tering, q = (k

0

− k

1

) is the momentum transferred to the atom, r represents

the coordinate of the fast electron, V(r) is the potential (energy) responsible for the

interaction, and the asterisk denotes complex conjugation of the wavefunction; the

integration is over all volume elements dτ within the atom.

Below an incident energy of about 300 keV (see Appendix A), the interaction

potential that represents electrostatic forces between an incident electron and an

atom can be written as

V(r) =

Ze

2

4πε

0

r

−

1

4πε

0

Z

j=1

e

2

r −r

j

(3.21)

Although generally referred to as a potential, V(r) is actually the negative of the

potential energy of an electron and is related to the electrostatic potential φ by

V = eφ.

The first term in Eq. (3.21) represents Coulomb attraction by the nucleus,

charge =Ze; the second term is a sum of the repulsive effects from each atomic elec-

tron, coordinate r

j

. Because the initial and final state wavefunctions are orthogonal,

the nuclear contribution integrates to zero in Eq. (3.20), so whereas the elastic cross

section reflects both nuclear and electronic contributions to the potential, inelastic

scattering involves only interaction with the atomic electrons. Because the latter are

comparable in mass to the incident electron, inelastic scattering involves apprecia-

ble energy transfer. Combining Eqs. (3.20) and (3.21), the differential cross section

can be written in the form

dσ

n

d

=

4γ

2

a

2

0

q

4

k

1

k

0

|

ε

n

(q)

|

2

(3.22)

3.2 Inelastic Scattering 129

where the first term in parentheses is the Rutherford cross section for scattering

from a single free electron, obtained by setting Z = 1inEq.(3.3). The second term

(k

1

/k

0

) is very close to unity when the energy loss is much less than the incident

energy. The final term in Eq. (3.22), known as an inelastic form factor or dynamical

structure factor, is the square of the absolute value of a transition matrix element

defined by

ε

n

=

ψ

∗

n

j

exp(iq ·r

j

)ψ

0

dτ =

ψ

n

|

j

exp(iq ·r

j

)|ψ

0

(3.23)

Like the elastic form factor of Eq. (3.2), |ε

n

(

q

)

|

2

is a dimensionless factor that

modifies the Rutherford scattering that would take place if the atomic electrons were

free; it is a property of the target atom and is independent of the incident electron

velocity.

A closely related quantity is the generalized oscillator strength (GOS), given by

(Inokuti, 1971)

f

n

(q) =

E

n

R

|

ε

n

(q)

|

2

(qa

0

)

2

(3.24)

where R = (m

0

e

4

/2)(4πε

0

)

−2

=

2

/(2m

0

a

2

) = 13.6 eV is the Rydberg energy

and E

n

is the energy change associated with the transition. The differential cross

section can therefore be written in the form

dσ

n

d

=

4γ

2

R

E

n

q

2

k

1

k

0

f

n

(q) (3.25)

where (k

1

/k

0

) ≈ 1 −2E

n

(m

0

v

2

)

−1

can usually be taken as unity. In the limit q → 0,

the generalized oscillator strength f

n

(q) reduces to the dipole oscillator strength f

n

that characterizes the response of an atom to incident photons (optical absorption).

In many cases (e.g., ionizing transitions to a “continuum” of states) the energy-

loss spectrum is a continuous rather than discrete function of the energy loss E,

making it more convenient to define a GOS per unit excitation energy (i.e., per unit

energy loss): df

(

q, E

)

/dE. The angular and energy dependence of scattering are

then specified by a double-differential cross section:

d

2

σ

ddE

=

4γ

2

R

Eq

2

k

1

k

0

df

dE

(q, E) (3.26)

To obtain explicitly the angular distribution of inelastic scattering, the scattering

vector q must be related to the scattering angle θ.Forθ 1 rad and E E

0

, where

E

0

is the incident beam energy, it is a good approximation to take the components

of q as k

0

θ and k

0

θ

E

(see p. 192, Fig. 3.39) and to write

q

2

≈ k

2

0

(θ

2

+θ

2

E

) (3.27)

130 3 Physics of Electron Scattering

where the characteristic angle θ

E

is defined as

θ

E

=

E

γ m

0

v

2

=

E

(E

0

+m

0

c

2

)(v/c)

2

(3.28)

and v is the speed of the incident electron. The factor γ = m/m

0

takes account of the

relativistic increase in mass of the incident electron. A nonrelativistic approximation

is θ

E

= E/(2E

0

), which gives characteristic angles 8, 14, and 18% too low at E

0

=

100, 200, and 300 keV, respectively. Equation (3.26) can now be written as

d

2

σ

ddE

≈

4γ

2

R

Ek

2

0

1

θ

2

+θ

2

E

df

dE

=

8a

2

0

R

2

Em

0

v

2

1

θ

2

+θ

2

E

df

dE

(3.29)

At low scattering angles, the main angular dependence in Eq. (3.29) comes from the

Lorentzian (θ

2

+θ

E

2

)

−1

factor. The importance of the characteristic angle θ

E

is that

it represents the half-width at half maximum (HWHM) of this Lorentzian function.

The regime of small scattering angle and relatively low energy loss, where df/dE is

almost constant (independent of q and θ), is known as the dipole region.

For typical TEM incident energies (e.g., E

0

= 100 keV), the width of the

inelastic angular distribution is quite small (FWHM = 2θ

E

∼ 0.1 for outer-shell

excitation, typically a few milliradians for inner-shell excitation) and considerably

less than the angular width of elastic scattering; see Fig. 3.5. Consequently, inelas-

tic scattering broadens only slightly the diffraction spots or rings in the diffraction

pattern recorded from a crystalline specimen. However, the Lorentzian function has

long tails and half of the outer-shell excitation corresponds to angles greater than

about 10 θ

E

(see Fig. 3.15), so inelastic scattering arising from electronic excitation

can contribute substantially to the background of an electron-diffraction pattern.

3.2.3 Dielectric Formulation

The equations given in Section 3.2.2 are most readily applied to single atoms or to

gaseous targets, in the sense that the required generalized oscillator s trength can be

calculated (as a function of q and E) using an atomic model. Even so, Bethe theory

is useful for describing the inelastic scattering that takes place in a solid, particu-

larly from inner atomic shells. Outer-shell scattering is complicated by the fact that

the valence-electron wavefunctions are modified by chemical bonding. In addition,

collective effects are important, involving many atoms. An alternative approach is

to describe the interaction of a transmitted electron with the entire solid in terms of

a dielectric response function ε(q, ω). Although the latter can be calculated from

first principles in only a few idealized cases, the same response function describes

the interaction of photons with a solid, so this formalism allows energy-loss data to

be compared with the results of optical measurements.

Ritchie (1957) derived an expression for the electron scattering power of an

infinite medium. The transmitted electron, having coordinate r and moving with a

3.2 Inelastic Scattering 131

velocity v in the z-direction, is represented as a point charge −eδ(r −vt) that gener-

ates within the medium a spatially dependent, time-dependent electrostatic potential

φ(r, t) satisfying Poisson’s equation:

ε

0

ε(q, ω)∇

2

φ(r, t) = eδ(r, t)

The stopping power (dE/dz) is equal to the backward force on the transmitted elec-

tron in the direction of motion and is also the electronic charge multiplied by the

potential gradient in the z-direction. Using Fourier transforms, Ritchie showed that

dE

dz

=

2

2

πa

0

m

0

v

2

q

y

ω Im[−1/ε(q, ω)]

q

2

y

+(ω/v)

2

dq

y

dω (3.30)

where the angular frequency ω is equivalent to E/ and q

y

is the component

of the scattering vector in a direction perpendicular to v. The imaginary part of

[−1/ε(q, ω)] is known as the energy-loss function and provides a complete descrip-

tion of the response of the medium through which the fast electron is traveling. The

stopping power can be related to the double-differential cross section (per atom) for

inelastic scattering by

dE

dz

=

n

a

E

d

2

σ

ddE

ddE (3.31)

where n

a

represents the number of atoms per unit volume of the medium. For small

scattering angles, dq

y

≈ k

0

θ and d ≈ 2πθdθ ,soEqs.(3.30) and (3.31)give

d

2

σ

ddE

≈

Im[−1/ε(q, E)]

π

2

a

0

m

0

v

2

n

a

1

θ

2

+θ

2

E

(3.32)

where θ

E

= E/(γ m

0

v

2

) is the characteristic angle, as before. Equation (3.32)

contains the same Lorentzian angular dependence and the same v

−2

factor as the cor-

responding Bethe equation, Eq. (3.29). Comparison of these two equations indicates

that the Bethe and dielectric expressions are equivalent if

df

dE

(q, E) =

2E

πE

2

a

Im

−1

ε(q, E)

(3.33)

where E

2

a

=

2

n

a

e

2

/(ε

0

m

0

), E

a

being a “plasmon energy” corresponding to one free

electron per atom (see Section 3.3.1).

In the small-angle dipole region, ε(q, E) varies little with q and can be replaced

by the optical value ε(0, E), which is the relative permittivity of the specimen at an

angular frequency ω = E/. An energy-loss spectrum that has been recorded using

a reasonably s mall collection angle can therefore be compared directly with opti-

cal data. Such a comparison involves a Kramers–Kronig transformation to obtain

Re[1/ε(0, E)], leading to the energy dependence of the real and imaginary parts

132 3 Physics of Electron Scattering

(ε

1

and ε

2

)ofε(0, E), as discussed in Section 4.2. At large energy loss, ε

2

is small

and ε

1

close to 1, so that Im(−1/ε) = ε

2

/(ε

2

1

+ε

2

2

)

1/2

becomes proportional to

ε

2

and (apart from a factor of E

−3

) the energy-loss spectrum is proportional to the

x-ray absorption spectrum.

The optical permittivity is a transverse property of the medium, in the sense

that the electric field of an electromagnetic wave displaces electrons in a direc-

tion perpendicular to the direction of propagation, the electron density remaining

unchanged. On the other hand, an incident electron produces a longitudinal dis-

placement and a local variation of electron density. The transverse and longitudinal

dielectric functions are precisely equal only in the random-phase approximation

(see Section 3.3.1) or at sufficiently small q (Nozieres and Pines, 1959); neverthe-

less, there is no evidence for a significant difference between them, as indicated

by the close similarity of Im( −1/ε) obtained from both optical and energy-loss

measurements on a variety of materials (Daniels et al., 1970).

3.2.4 Solid-State Effects

If Bethe theory is applied to inelastic scattering in a solid specimen, one might

expect the generalized oscillator strength (GOS) to differ from that calculated for

a single atom, due to the effect of chemical bonding on the wavefunctions and the

existence of collective excitations (Pines, 1963). These effects change mainly the

energy dependence of df/dE and of the scattered intensity; the angular dependence

of inelastic scattering remains Lorentzian (with half-width θ

E

), at least for small E

and small θ.

Likewise, changes in the total inelastic cross section σ

i

are limited to a mod-

est factor (generally ≤3) because the GOS is constrained by the Bethe f-sum rule

(Bethe, 1930):

df

dE

dE = z (3.34)

The integral in Eq. (3.34) is over all energy loss E (at constant q) and should be

taken to include a sum over excitations to “discrete” final states, which in many

atoms make a substantial contribution to the total cross section. If the sum rule is

applied to a whole atom, z is equal to the total number Z of atomic electrons and

Eq. (3.34) is exact. If applied to a single atomic shell, z can be taken as the number

of electrons in that shell, but the rule is only approximate, since the summation

should include a (usually small) negative contribution from “downward” transitions

to shells of higher binding energy, which are in practice forbidden by the Pauli

exclusion principle (Pines, 1963; Schnatterly, 1979).

Using Eq. (3.33), the Bethe sum rule can also be expressed in terms of the energy-

loss function:

3.2 Inelastic Scattering 133

Im

−1

ε(E)

EdE=

π

2

zn

a

e

2

2ε

0

m

0

=

π

2

E

2

p

(3.35)

where E

p

= (ne

2

/ε

0

m

0

)

1/2

is a “plasmon energy” corresponding to the number of

electrons, n per unit volume, that contribute to inelastic scattering within the range

of integration.

According to Eq. (3.29), the differential cross section (for θ θ

E

) is propor-

tional to E

−1

df /dE, and df/dE is constrained by Eq. (3.34); therefore, the cross

section σ

i

(integrated over all energy loss and scattering angle) must decrease if

contributions to the oscillator strength shift toward higher energy loss. This upward

shift applies to most solids because the collective excitation of valence electrons

generally involves energy losses that are higher than the average energy of atomic

valence-shell transitions. As a rough estimate of the latter, one might consider the

first ionization energy (Inokuti, personal communication); most often, the mea-

sured valence-peak energy loss is above this value, as shown in Fig. 3.10,sothe

valence-electron contribution to σ

i

is reduced when atoms form a solid. The result-

ing decrease in σ

i

should be more marked for light elements where the valence shell

accounts for a larger fraction of the atomic electrons and therefore makes a larger

percentage contribution to the cross section (Inokuti et al., 1981). A fairly extreme

example is aluminum, where the inelastic cross section per atom is a factor of about

3 lower in the solid, in rough agreement with the ratio of the plasmon energy (15 eV)

and the atomic ionization threshold (6 eV).

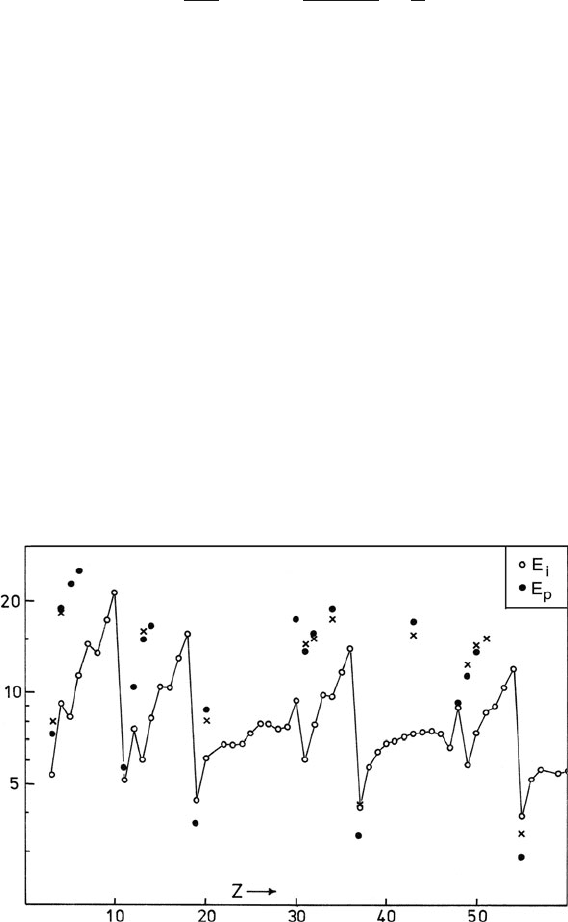

Fig. 3.10 First ionization energy E

i

(open circles) and measured plasmon energy E

p

(filled circles)

as a function of atomic number. Where E

p

> E

i

, an atomic model is expected to overestimate the

total amount of inelastic scattering. Crosses represent the plasmon energy calculated on a free-

electron model with m = m

0

134 3 Physics of Electron Scattering

Some solid compounds show less pronounced collective effects and the inelastic

scattering from valence electrons retains much of its atomic character. As a rough

approximation, each atom then makes an independent contribution to the scattering

cross section. The effect of chemical bonding is to remove valence electrons from

electropositive atoms (e.g., Na and Ca) and reduce their scattering power, whereas

electronegative atoms (O, Cl, etc.) have their electron complement and scattering

power increased. On this basis, the periodic component of the Z-dependence of σ

i

(Fig. 3.9), which is related to the occupancy of the outermost atomic shell, should be

less in the case of solids. In any event, what is measured experimentally is the sum of

the scattering from all atoms (anions and cations); if the reductions and increases in

scattering power are equal in magnitude, the total scattering power is simply the sum

of the scattering powers calculated on an atomic model. This additivity principle

(when applied to the stopping power) is known as Bragg’s rule and is believed to

hold t o within ≈5% accuracy (Zeiss et al., 1977) except for any contribution from

hydrogen, which is usually small anyway. It provides some justification for the use

of atomic cross sections to calculate the stopping power and range of electrons in

solids ( Berger and Seltzer, 1982).

Fano (1960) suggested that the extent of collective effects depends on the value

of the dimensionless parameter:

u

F

(E) =

2

ne

2

ε

0

m

0

df

d(E

2

)

=

2

ne

2

2ε

0

m

0

1

E

df

dE

(3.36)

where n is the number of electrons per unit volume (with binding energies less

than E) that can contribute to the scattering at an energy E. Collective effects can

be neglected if u

F

1, but are of importance where u

F

approaches or exceeds 1

within a particular region of the loss spectrum (Inokuti, 1979). Comparison with Eq.

(3.33) shows that u

F

= Im[−1/ε(E)]/π , so the criterion for neglecting collective

excitations becomes

Im[−1/ε(E )] π (3.37)

Equation (3.37) provides a convenient criterion for assessing the importance of

collective effects, since any energy-loss spectrum that has been measured up to a

sufficiently high energy loss can be normalized, using Eq. (3.35)or(4.27), to give

the energy-loss function Im[−1/ε], as described in Section 4.2. A survey of experi-

mental data indicates that Im[−1/ε] rises to about 30 in Al, 3 to 4 for InSb, GaAs,

and GaSb (materials that support well-defined plasma oscillations), reaches 2.2 in

diamond, and does not rise much above 1 in the case of Cu, Ag, Pd, and Au, where

plasma oscillations are strongly damped (Daniels et al., 1970).

Organic solids are similar in the sense that their energy-loss function generally

reaches values close to 1 for energy losses around 20 eV (Isaacson, 1972a), imply-

ing that both atomic transitions and collective effects contribute to their low-loss

spectra. Aromatic compounds and those containing C = C double bonds also show

a sharp peak around 6–7 eV, sometimes interpreted as a plasmon resonance of the π

3.3 Excitation of Outer-Shell Electrons 135

electrons. However, vapor-phase aromatic hydrocarbons give a similar peak, which

must therefore be interpreted in terms of π − π

∗

single-electron transitions (Koch

and Otto, 1969).

Ehrenreich and Philipp (1962) proposed more definitive criteria for the occur-

rence of collective effects (plasma resonance), based on the energy dependence of

the real and imaginary parts ( ε

1

and ε

2

) of the permittivity. According to these cri-

teria, liquids such as glycerol and water, as well as solids such as aluminum, silver,

silicon, and diamond, all respond in a way that is at least partly collective (Ritchie

et al., 1989).

3.3 Excitation of Outer-Shell Electrons

Most of the inelastic collisions of a fast electron arise from interaction with elec-

trons in outer atomic shells and result in an energy loss of less than 100 eV. In a

solid, the major contribution comes from valence electrons (referred to as conduc-

tion electrons in a metal), although in some materials (e.g., transition metals and

their compounds) underlying shells of low binding energy contribute appreciable

intensity in the 0–100 eV range. We begin this section by considering plasmon exci-

tation, an important process in most solids and one that exhibits several features not

predicted by atomic models.

3.3.1 Volume Plasmons

The valence electrons in a solid can be thought of as a set of coupled oscilla-

tors that interact with each other and with a transmitted electron via electrostatic

forces. In the simplest situation, the valence electrons behave almost as free parti-

cles (although constrained by Fermi–Dirac statistics) and constitute a “free-electron

gas,” also known as a “Fermi sea” or “jellium.” Interaction with the ion-core lattice

is assumed to be a minor perturbation that can be incorporated phenomenologically

by using an effective mass m for the electrons, rather than their rest mass m

0

, and by

introducing a damping constant or its reciprocal τ, as in the Drude theory of elec-

trical conduction in metals. The behavior of the electron gas is described in terms of

a dielectric function, just as in Drude theory. In response to an applied electric field,

such as that produced by a transmitted charged particle, a collective oscillation of

the electron density occurs at a characteristic angular frequency ω

p

and this resonant

motion would be self-sustaining if there were no damping from the atomic lattice.

3.3.1.1 Drude Model

The displacement x of a “quasi-free” electron (mass m) due to a local electric field

E must satisfy the equation of motion:

136 3 Physics of Electron Scattering

m

¨

x +m

˙

x =−eE (3.38)

For an oscillatory field: E = E exp(−iωt), Eq. (3.38) has a solution:

x = (eE/m)(ω

2

+iω)

−1

(3.39)

The displacement x gives rise to a polarization P =−enx = ε

0

χE, where n is

the number of electrons per unit volume and χ is the electronic susceptibility, and

Eq. (3.39) leads to

χ =

−enx

ε

0

m

=

−ne

2

ε

0

m

1

ω(ω +i)

=−ω

2

p

1

ω

2

+

2

−

i/ω

ω

2

+

2

(3.39a)

The relative permittivity or dielectric function ε(ω) is then

ε(ω) = ε

1

+iε

2

= 1 +χ = 1 −

ω

2

p

ω

2

+

2

+

i ω

2

p

ω (ω

2

+

2

)

(3.40)

Here ω is the angular frequency (rad/s) of forced oscillation and ω

p

is the natural or

resonance frequency for plasma oscillation, given by

ω

p

= [ne

2

/(ε

0

m)]

1/2

(3.41)

A transmitted electron represents a sudden impulse of applied electric field, contain-

ing all angular frequencies (Fourier components). Setting up a plasma oscillation

of the loosely bound outer-shell electrons in a solid is equivalent to creating a

pseudoparticle of energy E

p

= ω

p

, known as a plasmon (Pines, 1963).

Taking m = m

0

and writing electron density as n = zρ/(uA) where z is the

number of free (valence) electrons per atom, u is the atomic mass unit, A represents

atomic weight, and ρ is the specific gravity (density in g/cm

3

)ofthesolid,the

free-electron plasmon energy is conveniently evaluated as

E

p

= (28.82 eV) (zρ/A)

1/2

(3.41a)

For a compound, A becomes the molecular weight and z the number of valence

electrons per molecule.

In this free-electron approximation, the energy-loss function is given by

Im

−1

ε(ω)

=

ε

2

ε

2

1

+ε

2

2

=

ωω

2

p

(ω

2

−ω

2

p

)

2

+(ω)

2

(3.42)

AsshownbyEq.(3.32), Im(−1/ε) represents the energy dependence of the inelastic

intensity at an energy loss E = ω (the energy-loss spectrum), so Eq. (3.42) can be

written as

3.3 Excitation of Outer-Shell Electrons 137

Im

−1

ε(E)

=

E

2

p

(E/τ )

(E

2

−E

2

p

)

2

+(E/τ )

2

=

E(E

p

)E

2

p

(E

2

−E

2

p

)

2

+(E E

p

)

2

(3.43)

where E

p

is the plasmon energy and τ = 1/ is a relaxation time. The energy-loss

function Im(−1/ε) has a full width at half-maximum (FWHM) given by E

p

=

= /τ and reaches a maximum value of ω

p

τ at an energy loss given by

E

max

= [E

2

p

−(E

2

p

/2)]

1/2

(3.43a)

For a material such as aluminum, where the plasmon resonance is sharp (E

p

=

0.5 eV), the maximum is within 0.002 eV of E

p

, but for the broad resonance found

in carbon, Eq. (3.43a)impliesthatE

max

is shifted to lower energy by about 2.1 eV.

From Eq. (3.40), the energy at which ε

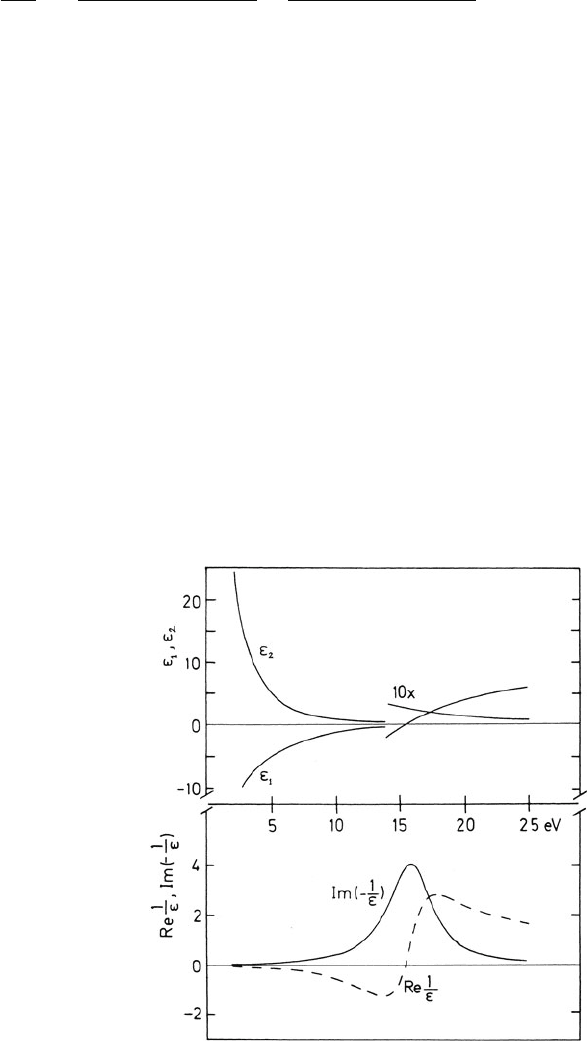

1

(E) passes through zero with positive slope

(see Fig. 3.11)is

E(ε

1

= 0) = [E

2

p

−(E

p

)

2

]

1/2

(3.43b)

This zero crossing is sometimes taken as evidence of a well-defined collective

response in the solid under investigation.

Although based on a simplified model, Eq. (3.43) corresponds well with the

observed line shape of the valence-loss peak in materials with sharp plasmon peaks,

Fig. 3.11 Real and

imaginary parts of the relative

permittivity and the

energy-loss function

Im(−1/ε), calculated using a

free-electron (jellium) model

with E

p

= 15 eV and

E

p

= 4 eV (Raether, 1980),

copyright Springer-Ve rlag