Deal W.E. Handbook To Life In Medieval And Early Modern Japan

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

maritime activity. Japanese ships sailed to Korea,

China, and as far away as Southeast Asia for trade and

also to transport embassies on their foreign missions.

In the Kamakura period, for instance, ships traded

with Southern Song–dynasty (1185–1333) China,

although this was not an extensive trade arrange-

ment. Both trade and the exchange of envoys

expanded in the Muromachi period. Ashikaga

shoguns promoted the so-called tally trade (see chap-

ter 4 for details) with Ming-dynasty (1368–1644)

China. These activities required the ability to build

boats both large and strong enough to make the haz-

ardous ocean crossing. In the medieval period, sail-

ing ships were constructed expressly for trade and for

dispatching envoys to China and Korea.

Ocean travel was possible, in part, because of

advances in technology. Among significant advance-

ments in the medieval period was the use of naviga-

tional charts that included latitude and longitude

markings. Charts became available for areas includ-

ing China, Korea, and Southeast Asia. By the end of

the medieval period, the magnetic compass and such

astronomical instruments as the quadrant and the

astrolabe were being utilized for more accurate nav-

igation, especially on long voyages.

Another aspect of medieval maritime travel and

communication that impacted both the movement

of ships generally and trading vessels in particular

was the activity of Japanese pirates (wako). Although

wako were referred to as Japanese pirates, in fact,

Koreans, Chinese, and others sometimes partici-

pated in these illegal bands. Active mostly in the

medieval period, pirates attacked and pillaged

the coasts of both Korea and China. In the 13th cen-

tury, pirates raided the coast of Korea, and such

attacks continued intermittently for two centuries.

Although the Korean government appealed to the

shogunate to control the pirates, they were mostly

ineffective in dealing with the problem. In the late

14th century, Korea successfully fought back against

the pirates, though pirate activities continued in

diminished form through the 16th century.

By the middle of the 14th century, Japanese

pirates were venturing further from Japan. They

attacked the Chinese coast in 1358, and for the next

200 years they continued to harass Chinese commu-

nities up and down the mainland coast. In an effort

to combat these raids, the Chinese set up coastal

defenses and limited coastal trade. One result of the

Japanese pirate activity was that the Chinese govern-

ment placed increasing pressure on Japan to control

or destroy the pirates. Trade agreements between

China and Japan began to hinge on the ability of the

shogunate to suppress pirate activity. The medieval

tally trade, for instance, was predicated on Japanese

control of pirate bands. During the Warring States

period, pirate activity increased because there was

no central power available to keep them in check. It

was only after Toyotomi Hideyoshi took control of

Kyushu—one of the staging grounds for pirates—in

his late 16th-century quest to unify Japan that pirate

activity diminished.

Early Modern Maritime

Travel and Communication

Medieval period accomplishments in foreign trade

and travel were abandoned in the early modern

period. International trade and long-distance travel

were forbidden by the Tokugawa shogunate once

the national seclusion policy was decreed in the first

half of the 17th century. In order to assure adher-

ence to this ban on international travel, the shogu-

nate further restricted the size of ships that could

legally be constructed. Thus, the order was issued

forbidding the building of ships with capacities of

more than 500 koku (49 gross tons).

In the Edo period, the development of a regu-

lated road system was vital to the expansion of travel

and communication, which were closely connected

to the development of the early modern economy.

Also vital to this process was the development and

improvement in maritime travel and transport capa-

bilities. To this end, maritime infrastructure—

including docks, warehouses, and canals—was built

or improved, and new coastal shipping routes were

established to better link the provinces with major

cities like Osaka and Edo.

Because of the ban on the construction of large

ships, domestic maritime travel was mostly restricted

to the use of small wooden sailing ships appropriate

for use on Japan’s coastal and inland waterways. Dur-

ing this time, such ships played a vital role in the

H ANDBOOK TO L IFE IN M EDIEVAL AND E ARLY M ODERN J APAN

334

expansion of the economy and the growth of urban

centers, such as Edo. Over time, the shogunate con-

tinued to forbid foreign trade and travel, but it did

relent on the maximum size of trading ships because

of their importance to the burgeoning domestic

economy that relied on coastal shipping to transport

rice and other staple goods from area to area. The

route between Osaka and Edo was particularly

important, as were routes from other areas of Japan

into these two large urban areas.

As the populations of urban centers grew over the

course of the early modern period, and consequently

the demand for essential commodities, the need for

more efficient transportation and distribution net-

works to deliver these goods to market also increased.

Osaka developed as a central collection and distribu-

tion center for goods produced in various parts of

Japan. It was necessary to create an efficient method

to transfer goods to Osaka, and then from there to

Edo. The transportation routes then in use combined

sea transport to a particular collection point where

goods were offloaded from ships and taken by land to

Edo, Osaka, or some other destination. The solution

was to use ocean routes that linked provincial ports

directly with Osaka, and Osaka with Edo.

The Tokugawa shogunate embarked on such a

project in the latter half of the 17th century when it

engaged the wealthy merchant Kawamura Zuiken

(1617–99) to establish new coastal shipping routes.

Kawamura set up a complete circuit around Japan

using two primary routes, the eastern sea circuit

(higashi mawari) and the western sea circuit (nishi

mawari). Prior to Kawamura’s endeavor, ships had

avoided certain ocean areas because of the fear of

shipwrecks in particularly treacherous waters. Kawa-

mura charted the coastal waters and established light-

houses to guide ships through dangerous stretches of

ocean. The eastern sea circuit ran from the Sea of

Japan to western Honshu and then through the

Inland Sea (Seto-naikai) to Osaka and Edo. The west-

ern sea circuit took ships from the Sea of Japan north

through the Tsugaru Strait and then down the Pacific

Ocean border of Japan into Edo Bay.

Japan’s isolation from most of the rest of the

world lasted more than 200 years, until it was inter-

rupted when Admiral Perry arrived in 1853 and

demanded that Japan open its ports to foreign trade.

Aside from the political fallout from this event, it

became evident to Japanese shipbuilders that Japan

had fallen behind technologically in its ship designs.

The subsequent Meiji period witnessed not only the

revival of foreign trade, but the design and construc-

tion of new ships using Western technologies. Alter-

nate modes of propulsion, such as steam engines,

were introduced at this time.

Examples of Boat and

Ship Types

Boats and ships were an important mode of domestic

and international travel in the medieval and early

modern periods. Because of their diverse uses, ships

came in many different sizes and shapes but were

always made of wood or other natural materials, until

the end of the early modern period when Western

shipbuilding techniques were formally introduced to

Japan. Ships used for trade were built in ways differ-

ent from ships used in warfare. A fishing boat was

appointed differently than a boat used to take

leisurely cruises down a river. The boats that carried

lords to their duties in Edo were different from the

boats that carried sake to market. The following list

details some of the different kinds of ships and boats

in use during the medieval and early modern periods.

ATAKE-BUNE

The atake-bune was a type of naval warship that was

used in battles during the Warring States period and

into the early Edo period. These vessels were any-

where from about 20 to 65 feet in length. Atake-bune

included a wooden tower from which arrows or

matchlock guns could be fired at the enemy. Twenty to

25 oarsmen were needed to propel these large ships.

BEZAISEN

Bezaisen, also known as sengoku-bune (1,000-koku

ships), were large ships widely used from the end of

the medieval period to transport goods to market.

These ships had a flat keel and were propelled by a

single square sail on one mast. The earliest bezaisen

had a relatively small capacity, but as the need to

carry more commodities per voyage increased, so

T RAVEL AND C OMMUNICATION

335

did the capacity of the newer versions of this ship

design. By the beginning of the 18th century, the

usual capacity of a bezaisen was 1,000 koku (98 gross

tons), thus earning the vessel the name sengoku-bune.

These larger bezaisen carried a crew of 15 or so.

They operated originally in the Inland Sea, but

later traveled a much longer distance, including voy-

ages in the southern part of the Sea of Japan and up to

Edo. These ships also sometimes took another route

to Edo, sailing through the strait between Honshu and

Hokkaido, and then traveling south to Edo. From the

beginning of the early modern period, bezaisen played

an active role in the growth of domestic maritime

trade. Bezaisen were related to such other transport

ships as higaki kaisen and taru kaisen (see below under

kaisen) as well as kitamae-bune (see below).

CHOKI-BUNE

The choki-bune was a riverboat used especially in cities

as a water taxi to ferry passengers from shore to shore.

GOZA-BUNE

Generally, goza-bune were large boats used by aristo-

crats or high-ranking warriors. They were also

brightly decorated for use in a festival and on other

occasions. Goza-bune were built both for use in the

ocean and on rivers. Oceangoing goza-bune (umi-

goza-bune) were essentially warships used to demon-

strate a warrior’s power during peaceful times of the

Edo period. One famous example of an oceangoing

goza-bune was the ship known as Tenchi Maru, a ver-

milion-lacquered vessel built by the third Tokugawa

shogun, Iemitsu, in the 1630s.

In contrast, rivergoing goza-bune (kawa-goza-

bune) were elegant vessels designed for use by high-

ranking warriors for travel by river. Rivergoing

goza-bune used oars and poles instead of sails.

HIGAKI KAISEN

Higaki kaisen were cargo ships that transported

essential commodities—such as oil, vinegar, soy

sauce, wood, and cotton—from Osaka to Edo. A

kind of circuit ship (see kaisen), higaki kaisen were

related to the cargo ship known as a bezaisen (see

above). Higaki kaisen were used especially by the

Sakai merchants.

HIRATA-BUNE

The hirata-bune was a large riverboat from 50 to 80

feet long, similar to a takase-bune (see below). This

long and narrow boat with a flat bottom was used to

transport freight. The largest of the hirata-bune had

a capacity of 300 koku (53 gross tons).

KAISEN

The term kaisen, or “circuit ship,” is a generic term

for cargo ships used to ship goods on consignment or

to deliver goods to market. Such boats were first used

with some regularity in the middle of the 13th cen-

tury in the Inland Sea. By the late Kamakura period,

however, circuit ships were transporting goods back

and forth from distant ports both north and south.

The government issued maritime rules known as

kaisen shikimoku (literally, “circuit ship regulations”)

to regulate the use of circuit ships in trade.

From contemporary records, it is apparent that

circuit ships were important to economic growth in

the medieval period. Various kinds of circuit ships

were also central to the development of trade in the

early modern period, and are notably associated with

the transport of goods between Osaka and Edo. Cir-

cuit ships made good use of the new sea-circuit trade

routes established in the last half of the 17th century.

It was not until the late 19th-century importation of

Western technology, such as the steamship, that the

use of circuit ships diminished. See also higaki kaisen

and taru kaisen.

KEMMINSEN

In the last half of the 14th century, Ashikaga shoguns

inaugurated the so-called tally trade with Ming-

dynasty China (1368–1644). From 1404 to 1547, 17

missions involving 84 ships made the journey to

China. The ships that made this crossing were known

as kemminsen (ships dispatched to the Ming dynasty).

They combined two purposes: foreign trade and for-

eign relations. Thus, these ships carried both goods

to trade and official envoys, known as kemminshi

(envoys to the Ming dynasty). Merchants also accom-

panied these voyages. In total, a single ship might

carry as many as 200 people, including the crew.

Kemminsen were newly built to meet the needs of

these voyages. They were large: records report that

H ANDBOOK TO L IFE IN M EDIEVAL AND E ARLY M ODERN J APAN

336

they had a capacity between 1,000 and 2,500 koku

(between 98 and 245 gross tons). These ships sailed

using two masts with matted square sails. There was a

cabin on deck that was specially appointed to accom-

modate the needs and tastes of the envoys on board.

KITAMAE-BUNE

Kitamae-bune, also known as hokkoku-bune, were a

regional variation of a bezaisen (see above). These

were very large ships—some with a capacity as great

as 1,000 koku (98 gross tons)—used to transport

cargo during the Edo period. The term kitamae

means “northern area,” and kitamae-bune operated

from northern areas of the Sea of Japan transporting

commodities to markets in central Japan. Kitamae-

bune were designed so they could carry the greatest

capacity for their size. Although a square sail was the

primary means of propulsion, these ships could also

be rowed. Northern Japan was only sparsely popu-

lated, and few of its customs were known in the cen-

tral parts of Japan. One of the consequences of the

kitamae-bune trade was that northern styles of cloth-

ing, song traditions, and differences in dialect

became known to a wider Japanese audience.

SEKI-BUNE

Seki-bune was a type of Japanese warship used in the

Warring States period and at the beginning of the

early modern period. Unlike its contemporary, the

atake-bune, the seki-bune was much smaller and faster.

SHUINSEN

At the end of the Azuchi-Momoyama period and the

beginning of the early modern period, the govern-

ment tried to control overseas commerce and travel

by issuing trading permits known as “vermilion seal

licenses” (shuinjo) to those who desired to engage in

foreign trade. Merchants from Kyoto, Sakai, and

Nagasaki were particularly involved in international

trade under this arrangement.

The ships used by merchants with permits were

known as “vermilion seal ships” (shuinsen). Vermil-

ion seal ships were oceangoing sailing ships that

were built within Japan and also imported from

China and Siam (Thailand). These were large ships

that could be as much as 130 feet in length with a

capacity of up to 4,225 koku (750 gross tons). Their

design features were a hybrid of Chinese, Por-

tuguese, and Spanish ships. Shuinsen had three masts

and double keels. They reportedly used a crew of 80

and could accommodate as many as 320 passengers.

Before foreign trade was forbidden by the shogunate

in the 1630s, some 350 shuinsen voyages were made

to locations as far away as Southeast Asia.

TAKASE-BUNE

Like the hirata-bune, the takase-bune was a type of

long and narrow riverboat with a flat bottom. It was

used to transport freight (typically on the Takase

River) and also for work in rice paddies.

TARU KAISEN

Taru kaisen were cargo ships that were used specifi-

cally to transport sake in barrels (taru), though these

boats sometimes carried other products, from Osaka

to Edo. A kind of circuit ship (see kaisen), taru kaisen,

like the higaki kaisen, were related to the cargo ship

known as a bezaisen (see above). Taru kaisen were

propelled by a single sail and had reinforced hulls in

order to hold the heavy barrels they transported.

T RAVEL AND C OMMUNICATION

337

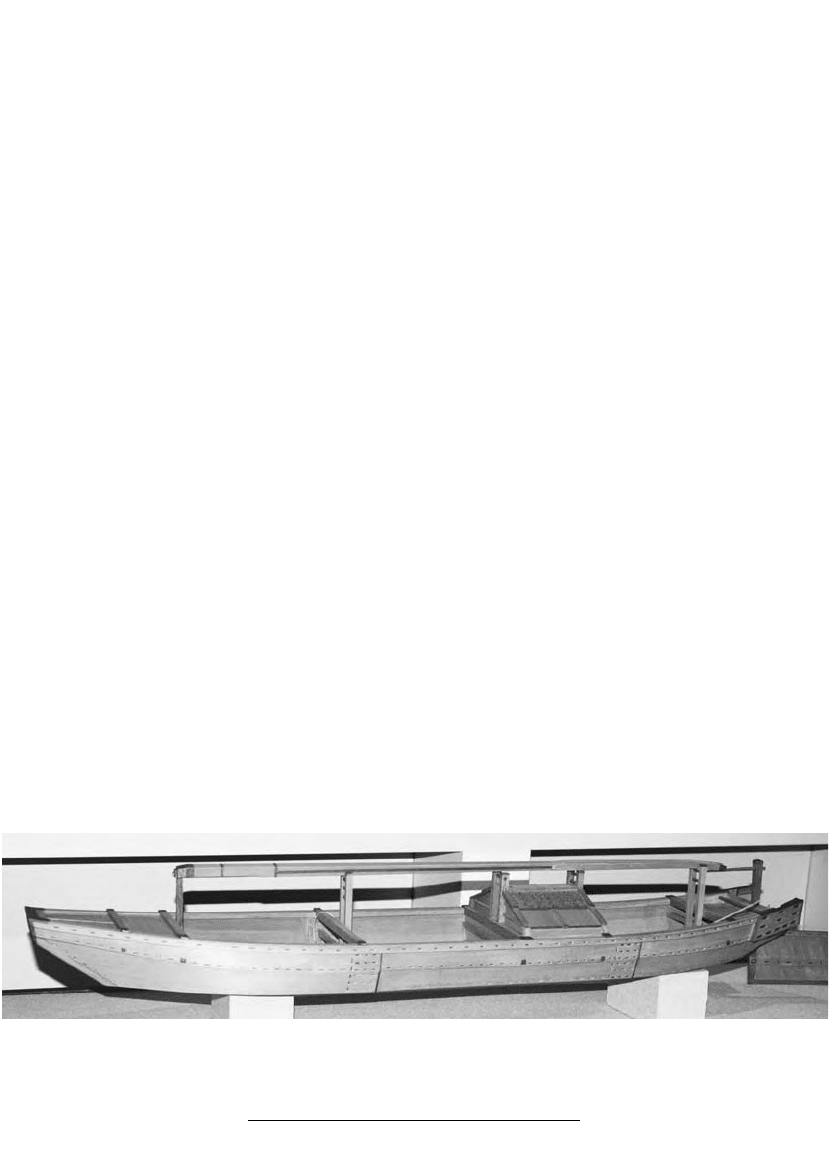

11.5 Model of a takase-style boat used during the Edo period (Edo-Tokyo Museum exhibit; Photo William E. Deal)

YAKATA-BUNE

Yakata-bune was a type of luxury riverboat used for

leisure activities by the wealthy.

YU-BUNE

An unusual boat, a yu-bune was a floating public bath.

At the center of the boat was an enclosed central

space for the bathtub. Water for the bath was heated

using firewood. Customers, who were typically crews

from cargo ships and dock workers, paid a fee to use

the bathing facilities on board the yu-bune.

EUROPEAN SHIPS IN JAPAN

Japanese exposure to the West in the transition

period from the medieval to the early modern

period, and again in the middle of the 19th century,

introduced the Japanese to new shipbuilding styles

and methods. In the early 17th century, for instance,

the Japanese built two English-style ships with the

guidance of Will Adams, an English sailor living in

Japan. With the help of the Spanish, a larger West-

ern-style ship was built a decade or so later. This

particular engagement with Western shipbuilding

was cut short, however, by the national seclusion

policy enacted by the Tokugawa government in the

1630s.

Interest in Western ships and shipbuilding was

revived when, in 1853, Admiral Perry sailed into

Uraga Bay in his “black ships” (kurofune), named for

their color. Of the four ships that Perry com-

manded, two used sails and two were steamships.

The Japanese were at once intrigued by the possibil-

ities of a steam-powered ship, but they were also

aware of the necessity of updating their own war-

ships to match the power of their Western rivals.

The government received a steam warship from

Holland and purchased another one. It was not until

the Meiji period, however, that Japan developed the

technology to build its own modern warships.

READING

Travel and Communication

Frédéric 1972, 88–89: travel in the medieval period;

Nishiyama 1997, 104–109: transportation and travel

in the early modern period, 132–135: Ise pilgrimage,

135–137: Kompira pilgrimage, 131–132: Kumano

pilgrimage, 139: Shikoku pilgrimage, 139–140:

Shinran pilgrimage, 137–139: 33 sites pilgrimage;

Dunn 1972, 23–28: samurai travel and roads in the

early modern period; Cullen 2003, 53: roads, 82–83:

commercial transportation, 89: Nakasendo, 88–90:

road traffic, 70, 89: Tokaido; Totman 1993, 153–157:

roads, travel, maritime transportation, and commu-

nication in the early modern period, 443–445: early

modern pilgrimage, 325–327: road construction and

maintenance in the early modern period, 71–72:

promotion of commercial travel in the early modern

period; Cortazzi 1990, 145–146: road and maritime

transportation in the early modern period; Totman

2000, 233–235: early modern roads and transporta-

tion; Totman 1974, 101–102, 116: early modern

communications; Jansen 2000, 134–141: early mod-

ern communication and travel; Yamamura (ed.)

1990, 364–366, 381–383: transportation in the

medieval period; Hall (ed.) 1991, 114–115, 117,

530–531, 551–553, 567–568: early modern trans-

portation; Jansen (ed.) 1989, 64–65: travel in the

19th century; Traganou 2004: travel and communi-

cation along the Tokaido in the Edo period

H ANDBOOK TO L IFE IN M EDIEVAL AND E ARLY M ODERN J APAN

338

EVERYDAY LIFE

12

THE FAMILY

Family Structure

Medieval and early modern Japanese society was hier-

archical. By the end of the 17th century, this hierar-

chy was divided, at least in the ideal, into four distinct

classes: samurai, peasant, artisan, and merchant. In

turn, this overarching hierarchical framework shaped

the composition of the family unit. Interclass mar-

riage was not legally permitted, thus forcing individu-

als to marry along socioeconomic lines. This

structure perpetuated the dominant hierarchical para-

digm, preventing individuals from attempting to

change their social and occupational status.

In both medieval and early modern Japan, the

basic family unit was the ie (house). While the ie tradi-

tionally consisted of a nuclear family, it typically

expanded to incorporate an assortment of other

members, including blood relatives, such as grand-

parents, and nonrelatives, such as servants and their

kin. In addition to being the foundational component

of social organization, the term ie also referred to

notions of family property, reputation, and the princi-

ple of continued familial succession. Typically, the

eldest son became the inheritor of the family. How-

ever, when there were no legitimate blood kin to

assume control, external heirs unrelated to the family

were often adopted into the household as successors

to carry on the family lineage. This ethos of genera-

tional continuity and heritage reflects the Confucian

influence on early modern Japanese culture. Particu-

larly during the Edo period, the upper classes adopted

the familial tenets of Confucianism, leading to the

priority of filial obligation, obedience, and loyalty.

Overall, individuals were expected to sacrifice their

own well-being or personal desires for the greater

good of the family structure. Ie as a unit or principle

can be seen throughout Japanese culture well before

the medieval era. However, ie was particularly promi-

nent during the Edo period when strong economic

developments allowed even commoners to establish

their own line of succession for the first time.

The traditional size of the ie was around five peo-

ple. If a person within the family was lost, extra

responsibility was either assumed by the other family

members (within poor classes) or delegated to ser-

vant workers (within wealthier families). The head of

the household (koshu) was traditionally male and held

the greatest responsibilities for running the ie. How-

ever, women could also assume a position at the helm

of the household when a suitable male was unavail-

able. Likewise, the female partner to the koshu was

usually the most powerful and respected woman in

the household; she retained the responsibilities of

overseeing the traditional household duties.

As this suggests, men alone were not the only

individuals who could wield power in early modern

Japanese society. Elaborating on this idea is the fact

that the koshu’s authority was often tempered and

undermined by the traditional moral principles of

obedience to all elders. This ethical standard was

valued highly, as it granted respect to all individuals

of elderly rank, regardless of their sex or position. In

this way, women and servants could also attain

esteem by exercising their duty to the ie.

Housework

During the normal day of a peasant woman, her

duties included daily chores, household work, and

often physically demanding agricultural labor. Such

activity kept lower-class women very busy, often

occupying their entire day. In contrast, wealthy

upper-class women, such as the spouses of warriors,

frequently enlisted the help of maids, servants, and

other helpers to assume the majority of daily house-

hold responsibilities. Even so, these women still

remained occupied in some manner or another—

complete idleness, regardless of gender or socioeco-

nomic position, was looked down upon in early

modern Japanese society. For instance, wealthier

women were still responsible for entertaining guests,

waiting on their husbands, and managing the house-

hold servants. Younger girls were also obligated to

assist in the process of completing household labor as

they were typically assigned the more tedious

responsibilities and less desired everyday chores.

Despite common assumptions to the contrary,

Japanese men also made significant contributions to

the work of the home by assisting in the child-rearing

H ANDBOOK TO L IFE IN M EDIEVAL AND E ARLY M ODERN J APAN

340

process. In particular, lower-class men were important

figures in educating their children. Often they were

instrumental in teaching their progeny vital vocational

skills needed on the farm or in the merchant trades.

Children

Children were often trained to be competent in

housework early on in life due to the general

demand of many families for household workers. It

was not uncommon for children to work collabora-

tively with older individuals to learn a specific trade

or skill. Even though formal schooling became

increasingly available during the later stages of the

Edo period, children still frequently received educa-

tion from their own parents within the home.

While some young Japanese received training at

home, the Edo period also developed the custom of

satogo offspring, children who were sent away from

the home to be raised by foster parents. Many par-

ents made arrangements to entrust their children to

rural peasants for several years. This was done in an

effort to give the satogo a stronger upbringing. Along

with the satogo children, the practice of infant aban-

donment known as sutego was also practiced in Japan

at this time. Ill or otherwise unwanted infants were

left at a predetermined location where a chosen

“finder parent” (hiroioya) would take in and raise the

child. The hiroioya were selected based on their

character, reputation, and child-rearing ability.

Another common practice involving children was

adoption. Differing from the contemporary concep-

tion of the process, Japanese adoption was often

employed as a means to ensure the legacy and

longevity of the family line. This was done particu-

larly when there was no appropriate natural male

successor to be the head of the household. Develop-

ing in the Kamakura period, adoption was also used

to create strategic associations and familial alliances.

The process of adoption became more detailed and

complex during the Edo period.

E VERYDAY L IFE

341

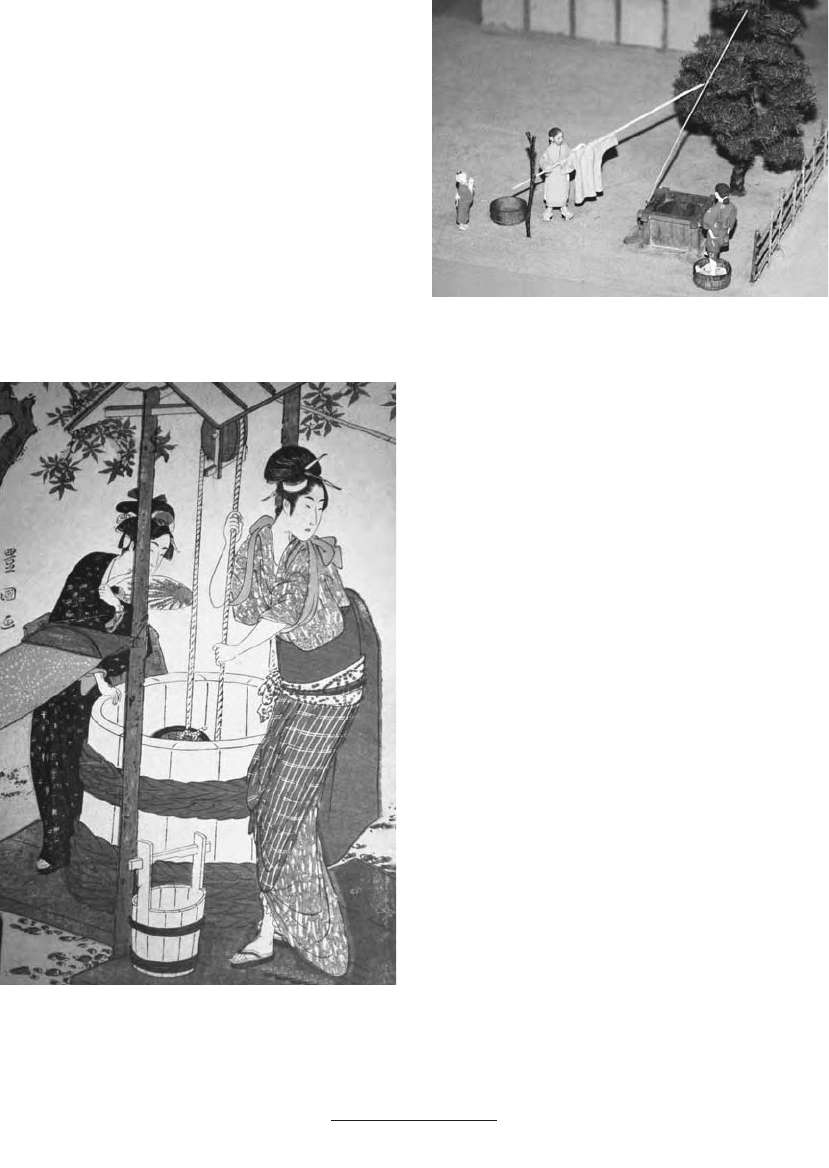

12.1 Scene of daily life in Edo: women drawing water

from a well

(Edo-Tokyo Museum exhibit; Photo William

E. Deal)

12.2 Model of a scene of daily life in Edo: hanging

laundry

(Edo-Tokyo Museum exhibit; Photo William

E. Deal)

Household Property

Because the ie was conceived of as an indissoluble

entity, its property and assets were never divided

among human constituents; instead, they always

belonged to the household as a larger collective.

This meant that no one individual, not even the

head of the household, could freely utilize the

material goods solely for personal gain. This sti-

pulation preserved the continuity of the household

for future generations. Changes in inheritance law

during the Edo period were detrimental to wo-

men: property was controlled by the head of the

household—typically male—and inheritances de-

scended through the male line of the family. Con-

sequently, women rarely had property in their own

name.

The ie was usually represented by only one in-

dividual, the household head, who was respected

for his rank, not individual personal merits.

Because of this emphasis on one representative per

household, in addition to the traditional customs

that discouraged females from registering their

names in the administrative records, women were

frequently prevented from being recognized or

involved in the social sphere. All of these factors

regarding the structure and rights of household

property systematically subordinated women, mak-

ing them very dependent upon the men within the

family.

THE HOME

(For specific information on the architecture and

building materials of the home see chapter 10: Art

and Architecture)

Due to the volatile conditions of climate and nat-

ural disasters, Japanese houses were often built as

temporary, adaptable structures rather than perma-

nent, fixed dwellings. Thus, despite an overall popu-

lation expansion during the 16th and 17th centuries,

there are few houses that have endured from that

time to today.

Furnishings

Traditional forms and styles of Japanese furniture

have been used consistently throughout the history

of the country with the only significant changes

being caused by an influx of Western ideas and influ-

ences. A variety of furnishings were common to the

Japanese home during the early modern period,

many of which were primarily constructed with

wood in combination with other materials such as

ceramics and lacquer.

Japanese houses commonly included relatively

few furnishings compared with other cultures whose

populations concentrated in urban centers or farm-

ing communities. Like other resources, residential

possessions differed in number and quality at various

levels of Japanese society. Interiors were sparsely

furnished, often with rudimentary items, in all but

the most prosperous households during the me-

dieval period. From the 16th century through the

Edo period, newly prosperous merchants, samurai,

and other members of the middle and upper classes

H ANDBOOK TO L IFE IN M EDIEVAL AND E ARLY M ODERN J APAN

342

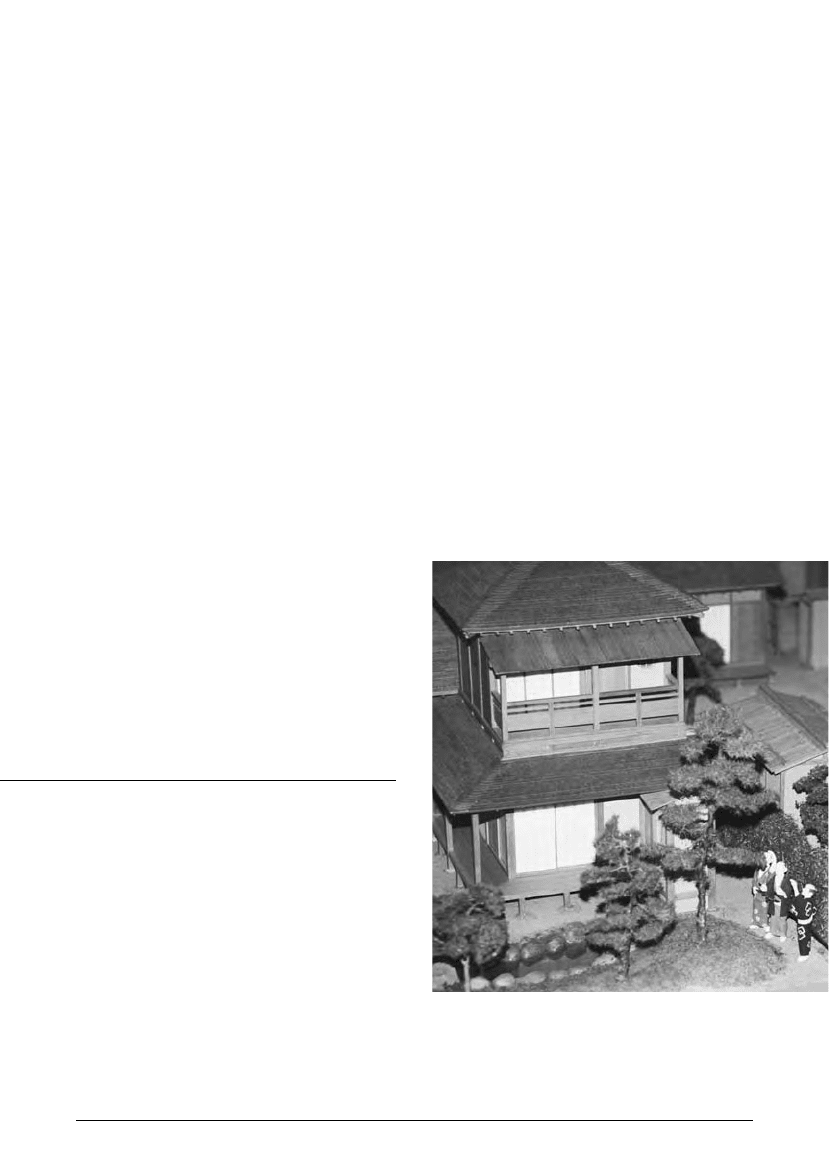

12.3 Model of the exterior of an Edo commoner’s house

(Edo-Tokyo Museum exhibit; Photo William E. Deal)

were able to outfit their homes with basic items such

as furniture and some luxuries. Still Japanese house-

holds possessed few furnishings compared with

dwellings in Europe or North America during the

16th through 19th centuries. The design of Japanese

interiors and the articles used inside were deter-

mined largely by the small size of most residences,

especially in cities. Some items found in family resi-

dences are categorized by type and summarized

below. Items such as screens and sliding doors,

which functioned both as part of an interior envi-

ronment and as artistic objects, are considered in

chapter 10: Art and Architecture.

Furniture and Other

Interior Objects

From medieval times, interiors in Japan consisted of

a floor—made of earth in farmhouses and other

humble dwellings, and wood planks in upper-class

residences or temples—which was covered with

tatami mats in structures inhabited by the middle

classes and above. From the late medieval period,

such floors were raised above the foundation level of

the structure. Room appointments included floor

cushions known as zabuton as well as tables and desks

(chabudai and tsukue) for serving or writing. These

were lower and often smaller in scale than similar

items used in the West. Medium-size storage cabi-

nets (kodansu, kodana, or todana, for shelves with

doors, or chigaidana, for open staggered shelves)

were sometimes made with unusual types of wood

appreciated for their decorative effect. Placement of

these cabinets was designed to harmonize with the

layout of a room, and the storage areas, complete

with drawers or open shelves, were sometimes per-

manent aspects of interior design. Cupboards, called

zushi, traditionally had the form of tiered shelves

(tanazushi) and could be disguised behind sliding

screen panels (shoji or fusuma). Usually cabinets and

cupboards were found only in upper-class dwellings.

Smaller freestanding boxes made from lacquer, or

bamboo, or other types of wood, were used for stor-

ing writing materials, cosmetics, food, and weapons.

Larger items were stored in chests (tansu) that

ranged from basic box forms to chests with drawers

adorned with precious materials and elaborate

designs. Other functional furnishings such as hibachi

(charcoal braziers), used for warming the interior of

a house, and iko, clothing stands or towel racks, were

found in many residences.

Japanese decor differed widely from Western

standards of furnishing. Rather than utilizing

numerous pieces of furniture to satisfy domestic

needs, the Japanese home often integrated features

into the structure of the building itself, making it

more streamlined than its Western counterpart.

Unlike the larger, unwieldy fixtures common in

Western culture, Japan used lighter, less bulky items

that were readily portable. For instance, cushions

and pillows served as substitutes for traditional

chairs and couches with legs; floor mats were used

instead of larger mattresses and bed frames; and

trays or smaller stands replaced larger tables. These

flexible furnishings allowed for efficient and easily

adaptable living arrangements that could meet dif-

ferent needs and changing conditions. This flexibil-

ity was especially important given the limited

natural and spatial resources at the disposal of most

Japanese families.

Bedding

FUTON

Typical Japanese bedding ensembles included a

futon, which is a mattress padded with cotton, wool,

or traditionally, straw. A futon is pliable and compact

enough to store out of sight in a cabinet or simply

set aside in a corner during the day, and later spread

on a floor (usually made of tatami) for sleeping at

night. Thus, due to the portable nature of Japanese

futon, a room could have many functions. A tradi-

tional futon set consists of a shikibuton (tufted or

padded mattress) and a kakebuton (thick quilted bed-

cover), which is placed on top of the mattress and

used as a covering for sleeping. Futon similar to

those used in Japan today probably originated in the

mid-16th century, replacing rush or straw mats, or

in modest settings, loose straw, materials that were

commonly used as bedding in the medieval period.

E VERYDAY L IFE

343