Deal W.E. Handbook To Life In Medieval And Early Modern Japan

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

QUILTS AND COVERLETS

Use of cotton or wool quilting for bedding first

began around the mid-16th century. Previously,

members of the ruling classes and samurai slept on

thick woven rush matting similar to tatami, and

commoners used mats of straw or loose straw. Cov-

erlets with sleeves and neckbands similar to such

daytime garments as kimono provided coverage. By

the mid-1500s, quilted covers—in a heavier weight

for winter and a lighter weight for summer—were

standard in many ruling-class residences.

MOSQUITO NETS

Evidence indicates that mosquito nets (kaya) have

been used in Japan since ancient times. By the early

Edo period, the nets were a standard summer item

found in houses at all social levels. Several sleepers

could be accommodated by the nets, which were

suspended overhead.

Standard Interior Structure

and Seating

By the early Edo period, items such as sliding doors,

tatami mats for flooring, and cushions for sitting on

the floor were standard furnishings in almost all

Japanese domestic settings. Such items were consid-

ered portable, although architectural in function,

and tenants were expected to install such items when

outfitting a new home.

Shoji and Other Types of

Sliding Doors

Sliding screens were in use in Japan from the Heian

period to separate one room from another, or to dis-

tinguish a passageway from a room. Sliding screens

with decoration on one or both surfaces were known

as fusuma shoji. These screens incorporated a remov-

able wooden door frame with cloth or paper applied

on both sides. Because they allowed diffused light to

enter, these sliding screens were also used as win-

dows and for interior ornamentation. Traditionally,

Japanese residences had shoji for room dividers and

terrace doors, as well as shoji-style fixed windows, to

allow air circulation when desired. Decorated slid-

ing doors (fusuma), and folding screens, which are

similar in construction to decorated fusuma, are

examined in chapter 10: Art and Architecture.

Tatami

This natural, woven mat has been used as a flooring

material in traditional Japanese-style rooms since at

least the Heian period. Tatami is a noun derived

from the Japanese verb tatamu, meaning “to fold or

pile.” The etymology of this word may correspond

to the original function of the mats, since evidence

suggests that thin woven tatami were piled in layers

to create a more cushioned surface, and could be

folded for storage when not in use. From the Muro-

machi period, tatami mats have been made with a

thick, straw base (toko) beneath a softer surface cov-

ering (omote) woven from rush (igusa). A fabric bor-

der was usually added to protect the edges from

fraying, and tatami were closely fitted, covering the

room from wall to wall. In some dwellings, rooms

with tatami were reserved for the most formal occa-

sions. Tatami dimensions differed from one geo-

graphic region to another.

Zabuton

These small, often slightly rectangular cushions

were designed for sitting on tatami mats or wooden

floors. Small rectangular portions of tatami fitted

with woven fabric borders were used for seating on

interior floors during the Heian period, and were

replaced by the Edo period with padded or cush-

ioned pillows stuffed with cotton batting. Tradition-

ally visitors were supplied with zabuton only during

the winter months, although ruling nobles or rank-

ing samurai would be more likely to use them

throughout the year.

H ANDBOOK TO L IFE IN M EDIEVAL AND E ARLY M ODERN J APAN

344

Heating and Lighting

The Japanese home was typically heated by a

centrally located fireplace. While medieval heat-

ing systems were somewhat inefficient and posed

numerous problems, heating techniques improved

with the development of the irori, an open, cen-

tralized fireplace around which several individu-

als could simultaneously receive heat, socialize,

or cook meals. Despite this advancement, early

modern heating still created a substantial amount

of smoke and soot that accumulated within the

home.

These factors contributed to an overall domestic

environment that was often dark and murky. Com-

pounding this problem was an overall lack of day-

light received into the home, as well as crowded

living conditions within townhouses. Wealthier

classes were able to use oil lamps to provide some

lighting, although these fixtures did not supply great

illumination. Lamps were not used with any fre-

quency by the lower classes, which instead employed

long wooden torches if light was needed. However,

the poor typically relied solely upon natural daylight

for their needs, basing their waking hours on the

cycle of the Sun.

MARRIAGE AND

DIVORCE

Marriage

Within the warrior class, marriage assumed great

political significance from the late 12th century

and extending into the Warring States period.

During that time, marriage functioned to create

familial associations and strategic political al-

liances for the samurai. Eventually, upper-class

warriors began to select wives from a greater dis-

tance than ever before in order to strengthen

such family connections. Within the marriage

itself, the samurai wife was expected to be able to

defend the home in the absence of her spouse and

was even given a dagger at her wedding for this

purpose.

As a philosophy advocated by the government,

Neo-Confucianism exerted much influence on war-

rior marital practices, something that can be seen in

the patrilocal traditions (yomeirikon) of the time.

Yomeirikon was the custom in which a woman

entered her husband’s abode and the couple lived in

close proximity to the man’s parents. This living

arrangement reflected the Confucian virtue of a

woman’s duty to her spouse. During the Edo period,

yomeirikon became more prominent, and while it was

traditionally practiced in the samurai classes, the

custom was eventually adopted by people of other

classes.

Generally, rural marriages were far less formal

than the maneuvering practices of the elite. Instead

they were marked by more unruly activity such as

yobai, “night visit,” a nocturnal sexual rendezvous.

The yobai occurred between both marital and pre-

marital couples and was commonly seen within the

mukoirikon living arrangement, when a wife would

reside with her parents. This practice was often

embellished, especially in folk traditions, and devel-

oped into an immoral activity subject to moral dis-

dain. But commoners began to adopt the marital

practices of the samurai during the Edo period,

diminishing these differences.

At this same time, other new marital develop-

ments occurred. Some of these included the yuino,

an engagement gift exchange, and the miai, a formal,

organized gathering of eligible marital partners

and their families. Marriages were highly regulated

during the Edo period as all unions were required to

be registered with and approved by governmental

officials.

Divorce

Marriage during the Edo period did not provide for

an egalitarian relationship between husband and

wife. While women were not afforded marital rights

with regard to divorce, men enjoyed substantial free-

dom in separating from their wives. Further, women

E VERYDAY L IFE

345

could be executed for adulterous activity, while men

were free to have affairs with concubine women.

For the divorce process, husbands had the sole

authority in deciding if the proper grounds for sep-

aration had been met. Their decision was not sub-

ject to regulation or administrative review. While

the samurai classes had a more complex divorce

process, a non-samurai male only had to give his

wife a three-and-a-half-line letter notifying her of

the separation, something which was not subject to

appeal.

Because the wife had no legal ability to divorce

her husband, one of her few options was to escape

to a Buddhist convent if she was unhappy or

abused. The refuge temples that provided such

safety for women were known as kakekomidera

(“temples to run into for refuge”). Under proper

conditions, the leaders of these asylums could issue

women a legal divorce if needed. The kakekomidera

were common from the 13th to the 19th centuries.

The two most famous—and the only formally

sanctioned “divorce temples” (enkiridera) during

the Edo period—were the Mantokuji (in Kozuke

province, northern Honshu) and the Tokeiji (in

Kamakura). Finally, although men retained the pri-

mary rights to a divorce, marital separation was

generally more of an organized, collaborative effort

between both families within the marriage, some-

thing which added a degree of equity to the

process.

Marriage Alternatives

There were some alternatives to the marital life for

Japanese women. Some exceptional, more talented

women could make a living through their trade or

vocation. However, the most common alternative

option was to enter the religious life or convent in

order to avoid marriage. Even though the religious

denial of marriage is seemingly contrary to the tradi-

tional Edo-period Confucian ideal of a woman’s

duty to labor in support of the domestic life, such

marriage alternatives were at least sometimes valued

by the authorities at the time. Often marital renun-

ciants would contribute to the household by sup-

porting their parents.

SEXUALITY

To a great degree, Japanese religious traditions were

quite liberal in their attitudes toward sex. Religious

narratives such as those found within the Kojiki are

filled with sexual imagery and symbolism. Japanese

culture was not ashamed of promiscuity; instead,

many practices suggest that society appeared to revel

in sexual activity. Some of these include the yobai

night visits and the kogai festival, which featured

songs, poetry, and premarital sexual activity among

young adults.

The unabashed, open attitudes toward sex were

especially found within the lower classes and folk

traditions. Festivals, songs, and tales often included

sexual references, and sexual activity abounded

among commoners during days of celebration and

revelry. Promiscuity was a common theme in much

of the popular literature of the day.

Homosexual relationships were also common at

the time, particularly between masters and disciples

at Buddhist temples and between samurai and elder

statesmen with political influence. Again, there was

no idea of shame or loss of status due to premarital

sexual activity. Thus, it was acceptable for men to be

engaged with multiple sexual partners. Concur-

rently, there was little reference to the concept of

virginity or sexual purity within medieval Japanese

culture.

As Japan developed an increasingly militaristic

and paternalistic society during the Edo period,

however, Confucian thought began to impact soci-

etal attitudes toward women and sexuality, much in

the same way it influenced marital arrangements at

that time. Consequently, these ideas and conven-

tions propagated more conservative views of sexual-

ity and fostered attempts to restrict the activities of

women so that their behaviors were in keeping with

Confucian values.

H ANDBOOK TO L IFE IN M EDIEVAL AND E ARLY M ODERN J APAN

346

PREGNANCY AND

CHILDBIRTH

Pregnancy

In the early modern period, the first decision to be

made by a family once it was discovered that a

woman was pregnant was whether or not the fetus

should be carried to term. Many families, especially

those who were feeding and clothing a number of

children already, felt that they could not afford to

bring another child into the world. Abortion,

despite being illegal and also dangerous to the life of

the mother given the lack of understanding about

infection, was not uncommon in the cities. The

countryside witnessed a different method of birth

control, namely smothering the baby after birth,

perhaps due to the family’s desire to discover if they

had conceived a son or a daughter before making

such a decision.

If the decision was made to carry the pregnancy

to term, special rituals were performed that were

believed to protect the health of both the mother

and her unborn fetus. One such ritual, obi iwai,

called for a sash (obi) to be tied round the mother’s

waist at the fifth month of pregnancy to help guar-

antee a safe and painless delivery. Depending on the

local customs, this sash could be fashioned out of a

loincloth belonging to the husband, or sent to the

mother-to-be by her parents, or even borrowed

from a shrine whose deity specialized in matters of

childbirth. As the weeks passed, the family made

religious prayers and offerings, and the mother was

cautious to avoid certain foods deemed detrimental

to the natal process.

Childbirth

According to Shinto tradition, birth was defiling

because blood caused ritual impurity. In order to

minimize this impurity, a family with sufficient eco-

nomic resources typically erected a special building

E VERYDAY L IFE

347

12.4 Scene of Edo-period urban domestic life: giving birth (Edo-Tokyo Museum exhibit; Photo William E. Deal)

outside the home, inside which the labor and deliv-

ery, overseen by a midwife, took place. The mother

delivered the child either in a squatting position or

in a specially designed bed, and the umbilical cord

was cut with a bamboo or steel knife. Seven days

later, relatives and friends were invited to pay a visit

to the new family. It was on this day that the new-

born received his or her name. (See “Shichiya” in the

section on Festivals and Yearly Rituals below.)

The upper classes often availed themselves of

foster mothers or wet nurses, particularly if the

mother was too busy to nurse or had died in child-

birth. A typical lower-class woman, however, rarely

spent a minute of her time apart from her infant. A

baby spent most of its daytime hours strapped to

its mother’s back by a broad cloth wrapped across

its back and underneath its buttocks. It was in-

termittently taken out for feedings which, it should

be noted, were carried on for far longer than

Western standards of that time. Even when the

child grew old enough to spend the night in its

own bed, it continued to sleep in the company of its

parents.

FOOD AND DRINK

Japanese eating customs varied widely depending on

socioeconomic status. Typically, religious figures

and those in the upper classes ate about two meals

per day, one before noon and the other in the late

afternoon or early evening. Later, following the lead

of the warrior classes during the mid-Edo period,

nobles and monks developed the habit of eating

three meals per day, with the largest meal being con-

sumed in the evening. Meanwhile, the poor involved

in physical labor might consume up to four meals a

day.

Buddhist dietary guidelines banned the con-

sumption of meat because it was deemed impure and

spiritually defiling. Correspondingly, nobles typi-

cally did not eat meat products, although some of

the upper class did enjoy it in secret. In contrast, it

was fairly common for those of the warrior and

lower classes to consume meat on a regular basis.

Cooking

Japanese cooking was filled with the staples of

seafood, marine vegetation, and rice. Because of reli-

gious stipulations, animal products were not typi-

cally used in food preparation. Instead, common

ingredients included soybean products such as miso,

a nutritious grain and soybean paste made with rice

or barley, and mirin, a sweetened version of sake

used in combination with vinegar and soy sauce.

Common spices used included ginger, wasabi (Japan-

ese horseradish) and sansho (a dried green powder

made from grinding the seedpods of the prickly ash

tree). Usually, these products could be found at local

town markets, which often had a great supply of

fruits, vegetables, seafood, and other food products

for the general populace.

In the 13th century, a form of cooking known as

shojin ryori (“diligence cuisine”) was introduced to

Japan by Chinese Zen monks. This is a form of veg-

etarian cooking that utilizes fresh, seasonal vegeta-

bles, seaweed, tofu, and other fresh ingredients

prepared in a simple manner. This form of Buddhist

cooking reflects the Buddhist admonition against

killing any form of life. During the Edo period,

Japanese cuisine acquired an assortment of new

influences from China, Korea, and Western coun-

tries such as Portugal and Spain.

Sake

One of the most popular drinks within Japan was

sake, or rice wine. This alcoholic beverage began as a

drink commonly consumed within group or social

settings, such as celebrations, festivals, or parties.

During the Edo period, however, sake developed

into an everyday drink that could easily be purchased

at local markets and was consumed with regularity.

Dining Etiquette

The manner in which meals were consumed

depended on several factors, including a family’s

H ANDBOOK TO L IFE IN M EDIEVAL AND E ARLY M ODERN J APAN

348

socioeconomic status and the rank of individual

members within a family, and could differ widely

from household to household. The male head of the

household, who typically dined with guests and, on

occasion, his eldest son, was served his meals by his

wife and/or daughter-in-law. The women dined sep-

arately from the men, catching quick bites of their

meal in the time between trips to serve the head of

household. The head’s wife was generally served by

her daughter-in-law and, in more affluent house-

holds, both of these women were assisted by maid-

servants.

The traditional style of serving meals was fairly

systematic. The person serving the meal would

place an individual lacquer tray, approximately

18 inches square and on legs roughly nine inches

high, in front of the diner. The entire meal, except

for the rice, was presented on this tray. The rice,

served next, constituted the bulk of the meal

and was therefore eaten in generous amounts.

Proper etiquette advised that one leave a few grains

of rice in the bowl when passing it back for more,

and it was not unusual for each person to consume

three full bowls of rice at a single meal. Either

disposable chopsticks (hashi) made of untreated

wood or reusable chopsticks made of lacquer, ivory,

or expensive metal were utilized during the meal.

The meal was officially concluded after green tea

made from the unfermented leaf (unlike the pow-

dered tea of the tea ceremony) had been served,

toothpicks had been utilized, and thanks had been

given.

The assortment of food items, like many other

things in life, was often an accurate indicator of a

family’s position in society. Those at the lower rungs

of Japanese society often ate markedly simple meals

consisting of a miso-based soup, vegetables, rice or a

mixture of rice and wheat, pickles, and tea.

E VERYDAY L IFE

349

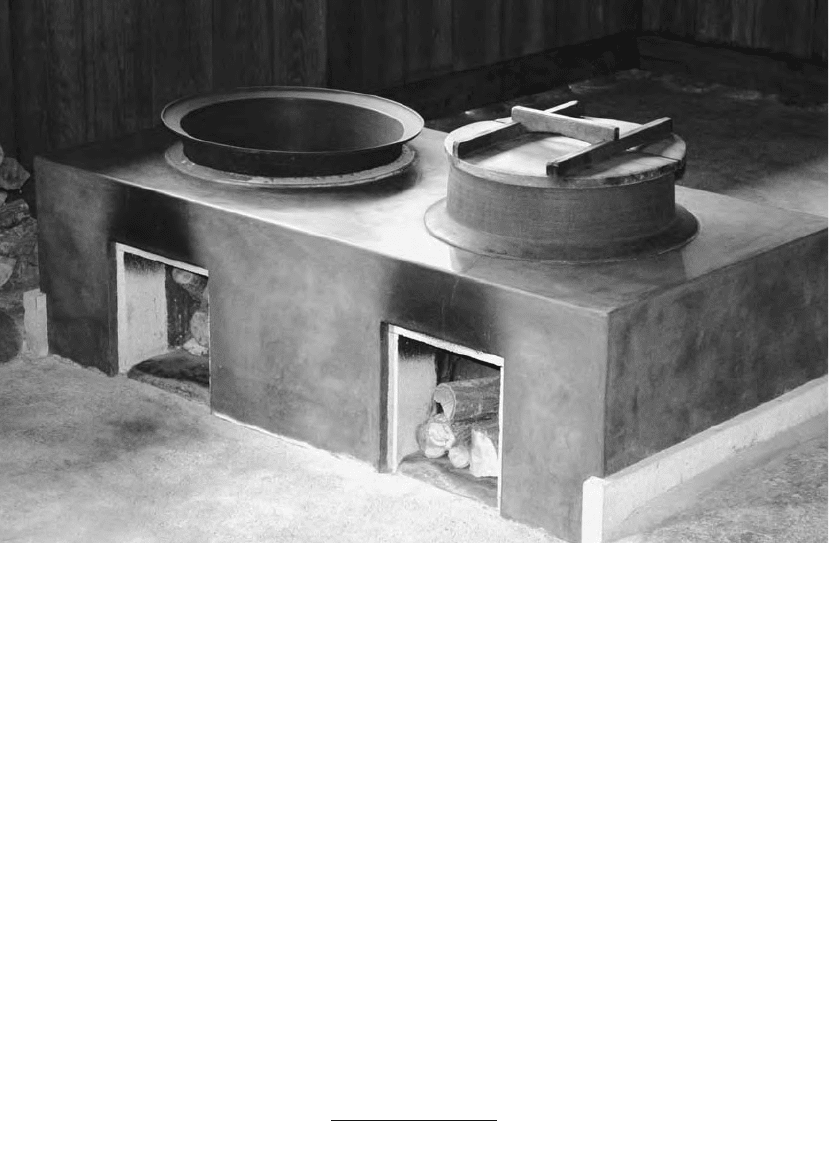

12.5 Kitchen stove in a traditional country home (Photo William E. Deal)

DRESS AND PERSONAL

APPEARANCE

Hair

Hair was a powerful symbol in Japan as it reflected

status, age, class, and sexuality. Samurai hairstyles

were pragmatic. Men wore their hair in a topknot,

and this style influenced commoner fashion in the

13th century. Women’s hair was usually long, worn

down, and kept straight. During the 16th century,

women began to put their hair up and utilize styles

that were more elaborate and decorative. Some-

times, women were punished by being forced to cut

their hair, a symbolic gesture representing humilia-

tion and debasement.

Most decorative hair ornaments were made of

bamboo, wood, tortoise shell, or ivory. One such

common item was the comb. Combs were crafted

out of gold and pearl in the medieval period. Elabo-

rate forms, styles, and designs developed during the

Edo period. Other decorative items found in the

early modern period included the stylized kanzashi

hair ornament and the kogai hairpin, used by both

men and women to manage their hair. Also develop-

ing in the Edo period were the kamiyui, hairstylists

who made house calls or opened up their own

salons, most notably within big cities.

Cosmetics and Accessories

Facial cosmetics were worn by both male and female

aristocrats on a regular basis during the medieval

and early modern periods. A pale complexion was

considered to be most desirable and was sought after

by many women. The traditional white face powder,

oshiroi, was often employed to achieve such an effect.

Other popular fashions for women included apply-

ing a red dot on their lower lip using a flower-based

paste, and the practice of okimayu, in which aristo-

cratic women shaved and re-drew their eyebrows

using a paint called mayuzumi. Okimayu was prac-

ticed starting in adolescence within the wealthy

classes and was practiced by everyday women during

special life events such as marriage and childbearing.

Beni was a rouge applied to the lips, and during the

18th century, sasabeni, a fashionable form of rouge

with a green hue, also became popular. Other skin

care items included nukabukuro, a face and body

wash made of rice bran, and various facial lotions

made from cucumber and gourd juice.

A common trend in dental fashion was ohaguro,

the practice of using an oxidized liquid to blacken

one’s teeth. This custom was thought to increase

attractiveness in addition to preserving the teeth.

While ohaguro was originally practiced only by

women, it became common among noblemen and

warriors during the 12th century before later revert-

ing to a practice only for women in the 18th century.

Tattoos as cosmetic items have a varied history in

medieval and early modern Japan. Until 1720, tat-

toos were used as punishments. Designs were placed

on the arm and face to mark offenses. In the Genroku

period (1688–1704), tattoos became fashionable

H ANDBOOK TO L IFE IN M EDIEVAL AND E ARLY M ODERN J APAN

350

12.6 Sake shop in Edo-period style (Photo William E.

Deal)

among prostitutes who often received kisho-bori tat-

toos or “pledge marks” to indicate their favorite

clients. However, tattoos reached their artistic and

popular peak during the mid-19th century. Especially

trendy among the townspeople, tattoos of the time

exhibited elaborate, colorful designs that often cov-

ered an extensive portion of the body. To make these

intricate, designs, great skill was needed, creating a

market for specialized tattoo artists called horishi.

A final type of fashion accessory was the fan or

uchiwa, used in a wide range of contexts, including

within battle, during ceremonies, and as personal

accessories. Folding fans, or ogi, were status symbols

that were also used in a variety of settings, including

dance performances, theatrical productions, and tea

ceremonies.

Clothing

During the Kamakura period, the typical warrior

uniform consisted of a hunting jacket, kariginu, and

a cloak (suikan). Women’s formal attire included the

uchiki robe and hakama skirt-trousers with the

kosode, a silk garment with short sleeves added to the

ensemble at a later time. The uchikake or kaidori, a

long jacket, developed in the Muromachi period,

while the kamishimo, a matching sleeveless top and

bottom ensemble worn by the samurai, arose during

the Azuchi-Momoyama period, an era in which

Japanese fashion began to show Chinese and Por-

tuguese influence. During the late 14th and early

15th centuries, the use of cotton became widespread

for people of all socioeconomic classes. Individuals

enjoyed the texture and washability of the fabric,

especially commoners, whose attire was often

uncomfortable. Led by the Kabuki theater fashions,

Edo-period clothing saw the expansion of elaborate,

lavish fashion designs, decorated with newly devel-

oped dyes. Toward the end of the period, the gov-

ernment placed restrictions on such overly flashy

attire, causing citizens to modify their standards of

E VERYDAY L IFE

351

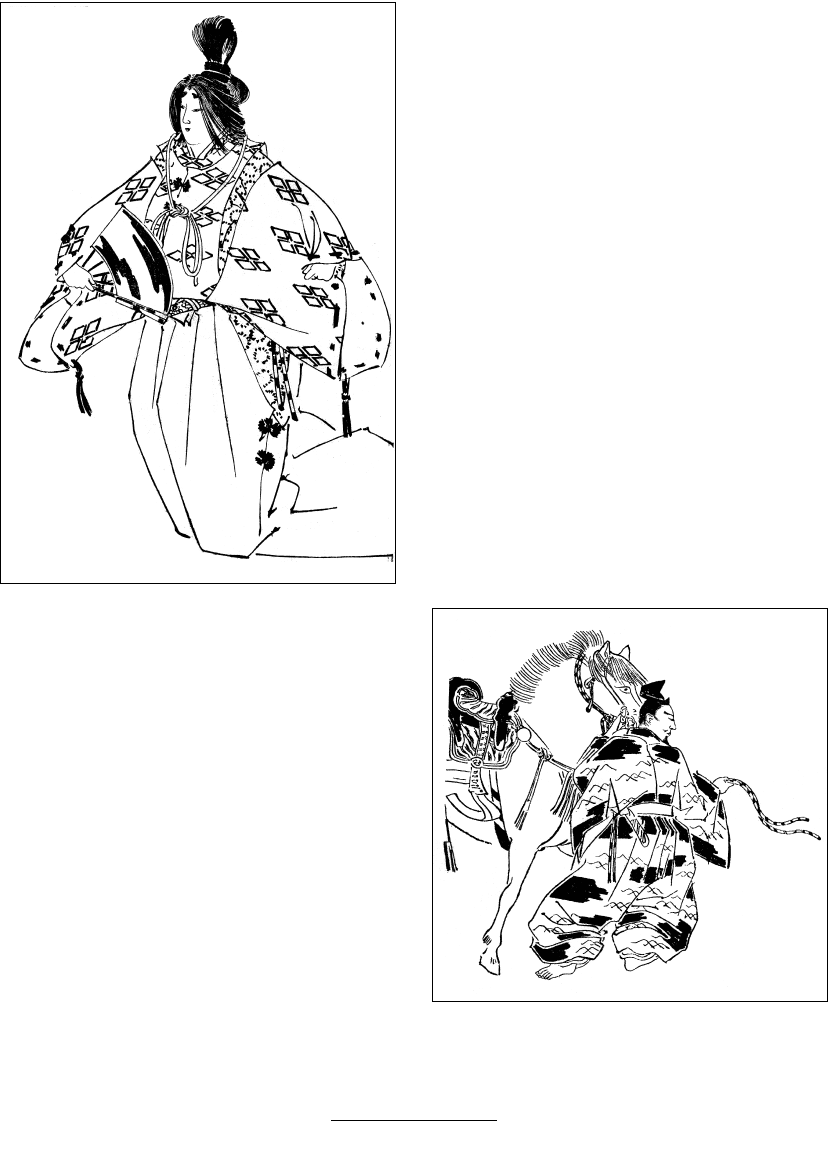

12.7 Kamakura-period aristocratic woman (Illustration

Kikuchi Yosai from Zenken kojitsu, mid-19th century)

12.8 Everyday medieval warrior attire (Illustration

Kikuchi Yosai from Zenken kojitsu, mid-19th century)

fashion and beauty. Typical apparel of this time

included the kosode, a sash, and the haori, a short

jacket. Military uniforms also incorporated the

kosode, hakama, and haori.

Commoners often wore simple outfits consisting

of a smock, trousers, and an overcoat. Women tradi-

tionally wore kimonos with girdles called yumaki,

often layered if the weather demanded. Sometimes

commoners went barefoot or wore straw sandals

called ashinaka. Due to especially hot summers,

nudity was acceptable and not subject to embarrass-

ment or scorn within the working classes. Thus, it

was not uncommon or inappropriate for men to

wear only a loincloth or for women to work the

fields topless.

While the shogunate stipulated that courtesans

should wear only simple clothing, it was clear that

they did not always follow such guidelines. Courte-

sans were, however, not permitted to wear any socks,

leaving them barefoot even during the winter.

Going barefoot became a valued symbol of disci-

pline for these women. Furthermore, naked feet

were considered sexually alluring, especially since

the courtesans often used nail polish.

Japanese clothing varied greatly among social

classes. Both the style and color of attire were mark-

ers of socioeconomic status and gender distinctions.

Despite this diversity, however, one article of cloth-

ing that was commonly used by people of all classes

was the kosode, or kimono, as it came to be known

during its widespread use in the 18th century. The

kimono was an efficient form of clothing—it was

easy to create, wasted no fabric in the manufacturing

process, and was readily adaptable to fit different

individuals and body types. Two special types of

kimono were the yukata, commonly worn in the

summer and made of white cotton occasionally with

blue dye, and the furisode, worn by young women of

nobility in the Edo period and marked by longer,

extended sleeves.

Traditional Japanese headgear included the kasa,

a hat made of straw, sedge, and other materials, and

often formed into different shapes symbolic of an

individual’s class status. Headcoverings included the

cotton cloth tenugui and zukin, and headbands called

hachimaki. Hachimaki were typically worn by indi-

viduals under great duress, such as warriors in battle,

women giving birth, and men involved in strenuous

physical labor.

Sandals were the most common form of foot-

wear, as they were cheap, convenient, and easy to

make. The most notable forms of such footwear

were the straw waraji used for long trips by foot,

geta, which were wooden clogs often worn by urban

dwellers, and zori, a sandal commonly worn with

kimono. Typical raingear included the kasa hat, the

Portuguese-influenced rain cape known as a kappa,

and a type of geta used as rain footwear, the ashida.

H ANDBOOK TO L IFE IN M EDIEVAL AND E ARLY M ODERN J APAN

352

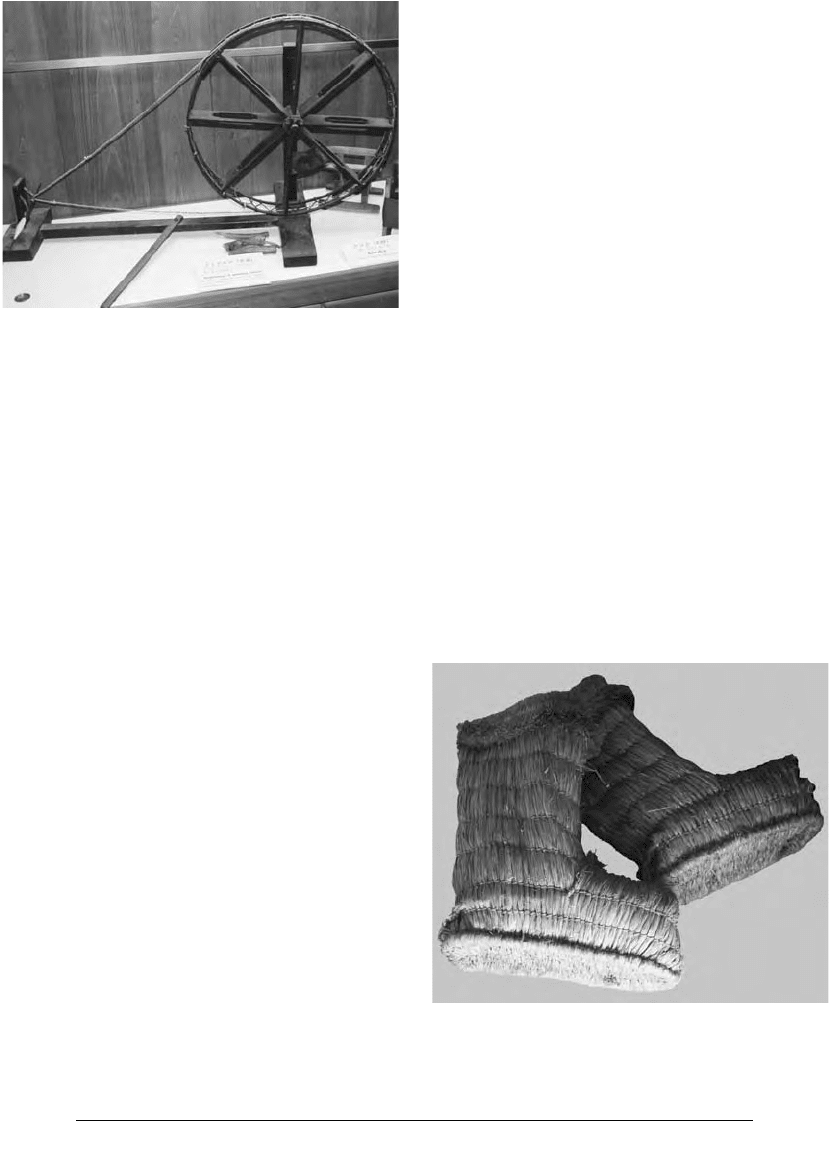

12.9 Edo-period spinning wheel (itoguruma) used for

making cloth

(Photo William E. Deal)

12.10 Straw boots (zunbe) worn in the countryside

during winter

(Photo William E. Deal)

Everyday Etiquette

Guidelines for personal decorum differed depending

on such factors as an individual’s social class, gender,

and rank within his or her family. For example, a

wife was expected to walk a pace behind her husband

when they appeared together in a public setting, a

relatively infrequent occurrence. In the household,

individuals were expected to situate themselves in a

very particular sitting position that had been taught

to them since childhood. Sitting back on the heels,

with the ankles nearly sideways on the floor, allowed

the feet to form a cup which comfortably accommo-

dated the buttocks. When a woman was receiving

guests, bidding farewell, or taking orders, she placed

her hands on the floor and bowed quite low to the

ground, lowering her forehead between her hands.

Men bowed in a similar fashion, but not quite so

low, and were permitted to sit in a cross-legged posi-

tion in less formal situations. Outside of the home,

people simply bowed to each other from the waist,

only demonstrating respect by bowing to the ground

when a personage of high authority, such as a

daimyo, passed by.

When greeting others, it was expected that

people would remove items worn for work, such

as protective clothing or spectacles. Since it

was considered rather rude to breathe on other

people, the custom was to position the hand in

front of the mouth while speaking to superiors.

For the same reason, when handling sacred or oth-

erwise important objects, a piece of paper was

placed in the mouth to protect the items from des-

ecration.

SPORTS AND

DIVERSIONS

Sports and Games

In addition to the martial arts outlined in chapter 5:

Warriors and Warfare, Japan also enjoyed a hand-

ful of other sporting activities. One of the most re-

nowned and distinctive of these sports was the form

of wrestling called sumo. In sumo two wrestlers,

wearing only a special loincloth belt called a ma-

washi, compete in a dohyo—a central clay ring

surrounded by bags of straw—where they must

force their opponent to step out of the circle or

touch the ground with any part of their body

except the feet. The match lasts for only a brief

amount of time and is arbitrated by the gyoji (ref-

eree). Sumo dates back to before the medieval

period, but it first became a professional sport dur-

ing the Edo period. Other sports included cock-

fighting, fishing, and falconry.

Outside of the traditional sports of the day, the

athletic kickball game kemari was popular among the

nobility during the Kamakura period. Kemari con-

sisted of people trying to kick a ball around a circle

while not letting it touch the ground. This game,

along with the associated handball temari, eventually

was picked up and enjoyed by the lower classes as

well. Hanetsuki—a badminton-like game played by

girls with wooden paddles and a shuttlecock—and

the otedama beanbag game were two other athletic

diversions found in early modern Japan.

Two of the most prominent board games played

in Japan were go and shogi. Go is a classic game of

strategy played by two individuals moving black and

white stones across a wooden board. During the

17th century, annual go matches were held for the

shogun at Edo castle. Go competition was excep-

tionally competitive and specialized schools were

established to train individuals in the art of playing

this game. Shogi was a related game that resembles

the Western game of chess. An official governmen-

tal agency to oversee go and shogi was established by

the Tokugawa shogunate in 1607. Finally, a board

game played with dice called sugoroku, comparable

to backgammon, became especially popular from

the 17th century. The goal of the game was to move

all of one’s pieces into the opponent’s territory. One

version of sugoroku was played on a board inscribed

with scenes of both the Buddhist Pure Land and

the Buddhist hells. The goal of Pure Land sugoroku,

as it was called, was to attain entry into the Pure

Land associated with Amida Buddha. (see chapter 6:

Religion, for details on the Pure Land school of

Buddhism.)

E VERYDAY L IFE

353