Deal W.E. Handbook To Life In Medieval And Early Modern Japan

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Besides board games, card playing was also a

common pastime. Two popular forms were the uta

karuta (poem cards), a game played with cards on

which a famous poem is written, and hanafuda

(flower cards), a game played with cards depicting

flora and fauna. Card playing was often associated

with gambling, both of which were banned by the

Tokugawa shogunate after a dramatic increase in

such activity.

Children’s play during the medieval and early

modern periods included the following games:

MENKO

Dating back to the Kamakura period, menko was a

game in which a player placed a game piece on the

ground. An opponent would try to flip the piece

over by flinging another game piece at the one on

the ground. These game pieces, made of clay or

some other material, were usually decorated. In the

Edo period, images of sumo wrestlers became a pop-

ular subject for the pieces.

KAGOME KAGOME

“Bird in a cage” game. This was a guessing game in

which children formed a circle around a child and

sang a song called “Kagome kagome.” While the

song was being sung, the children moved in a circle

around the child in the middle. When the song

ended, the children stopped circling and the one in

the middle tried to guess who stood immediately

behind him or her. A correct guess released the child

from the circle (or the bird from the cage), replaced

by the child whose identity had been guessed.

NEKKI

In this game, a one-foot-high wooden stake is placed

upright into the ground. The object of the game is to

knock down the stake by throwing a stick against it.

JANKEN

This is a game of “rock, paper, scissors.” Pairs of

children would say “jan, ken, pon” in unison and then

H ANDBOOK TO L IFE IN M EDIEVAL AND E ARLY M ODERN J APAN

354

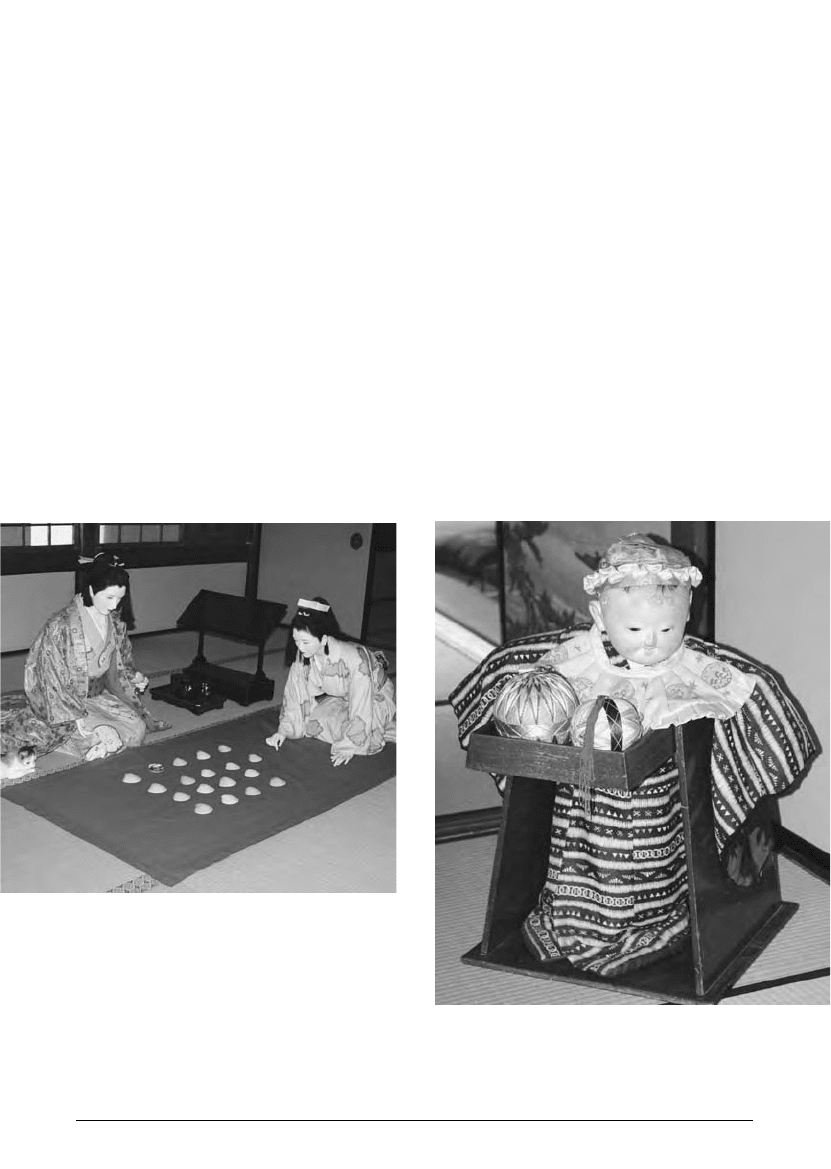

12.11 Princess Sen, eldest daughter of the second Toku-

gawa shogun Hidetada, engaged in an aristocratic pas-

time called kaiawase. From the Heian period, this

traditional game involved players competing to identify

shells with matching scenes or poems taken from classical

literature.

(Himeji Castle exhibit; Photo William E.

Deal)

12.12 Example of an Edo-period toy doll (Photo

William E. Deal)

hold out their hands. A closed fist was a stone, a

hand held out flat was paper, and a hand with two

fingers extended was scissors. Paper covered stone,

stone broke scissors, and scissors cut paper.

Other forms of leisure and entertainment found

throughout the medieval and early modern periods

included nazo nazo, the recitation of funny riddles

that became very popular during the Edo period,

and origami, the art of paper-folding to create intri-

cate shapes and figures. Flying elaborately decorated

kites, playing with children’s tops, and collecting

dolls that were often used in ceremonial celebrations

were additional leisure activities.

Household Pets

Children in medieval and early modern Japan rarely

possessed household pets. If an animal was cared for

by a human, it was usually because the animal served

some useful purpose. Insects such as crickets, valued

for the soothing effects of their chirping, and fire-

flies were often caught and kept in cages in Japanese

homes. Wild Japanese monkeys were sometimes

caught and trained to perform acts of entertainment,

such as dancing, for the public. With the exception

of some Pekinese dogs imported by the Dutch, dogs

in Japan were rarely kept as pets. Domestic cats,

imported into Japan in ancient times from China

and Korea, were rare and prized possessions until

the 10th century. However, by the Kamakura

period, they were fairly common in households as

vermin-catchers but not as treasured family pets.

The traditional Japanese breed of cat has been

described as short-haired, mostly white with black

and brown markings, and round-faced. Felines were

a common theme in traditional Japanese literature,

and folk beliefs revolved around the notion that cats

avenge themselves when killed.

Animals enjoyed significant protection under

Buddhism, which forbade the taking of any life. The

release of caged animals back into the wild was

highly regarded, and many people believed that such

an act would bring rewards in the next life. Mer-

chants on the street often sold live fish and caged

animals, such as birds and tortoises, specifically bred

or caught for this purpose.

CALENDAR

In the medieval and early modern periods, the

Japanese utilized the traditional lunar calendar.

Dates on this calendar represented the day, month,

and year, the last of which could be determined by

several methods. Two such methods included the

60-year time cycle and the use of the era name, or

nengo. Nengo was a unit of time comparable to an era,

commonly employed to date events or chronological

periods. The use of this measure of time began in

the seventh century. The change of emperor

included a change in era name. However, in the

early modern period, the nengo did not simply repre-

sent the duration of a governmental regime. New

era names might be declared when auspicious events

occurred or at certain points in the traditional 60-

year (sexagenary) calendar cycle.

Both telling time and naming months utilized

two separate methods. The time of day was typically

divided into 12 sections. Under the sexagenary sys-

tem, however, one set of six sections was not the

same time span as the other set. Likewise, months

had both formal or traditional names as well as alter-

native titles with symbolic folk meanings.

Despite the official use of the lunar calendar, the

solar calendar was also employed and was very

important for farmers. This calendar accurately pin-

pointed the seasons, and thus farmers depended

upon it to know the proper time for planting and

harvesting. In addition, the solar calendar was

important for the influence it had on the structure of

the traditional lunar calendar.

FESTIVALS AND

YEARLY RITUALS

As in other periods of Japanese history, festivals and

yearly rituals were important to the conduct of

everyday life in the medieval and early modern peri-

ods. Festivals (matsuri) have their origins in Shinto

E VERYDAY L IFE

355

rituals often associated with the agricultural cycle

and obtaining blessings from the kami for a plentiful

harvest and other benefits. Annual rituals (nenchu

gyoji or nenju gyoji) were related originally to the

imperial court calendar and date back to before the

medieval period. These annual rites often had a

Buddhist or astrological significance and were

intended to ensure the blessings of the Buddhas and

bodhisattvas, as well as the proper functioning of the

court. In the medieval and early modern periods,

especially with the reduced significance of the impe-

rial court, there came to be shared elements between

festivals and yearly events.

Festivals

Often tracing their origins to folk traditions, Japan-

ese festivals were numerous in the medieval and

early modern periods. Festivals existed in a multi-

tude of forms, and were present in all seasons and

regional locations. Despite the diversity of form, the

purpose of matsuri typically was to cultivate har-

mony within the local community and to effect

human-divine contact—often as a means to express

gratitude to the kami or to petition them for assis-

tance in agricultural matters. Because festivals were

often held to assure an abundant harvest, the occur-

rence of matsuri was tied to the seasonal cycle. Thus,

the most important celebrations occurred during the

spring and autumn to coincide with the planting and

harvesting periods. However, winter and summer

festivals were also held, the latter of which were

often rituals conducted to prevent the occurrence of

anything that might destroy the crops in midseason.

In the early modern period, city festivals arose as a

means to protect the population from epidemics and

natural disasters. Although there was obvious reli-

gious significance to matsuri, they also came to have

a more general celebratory tone and included events

such as dancing and contests.

Festivals included ritual elements that made it

possible to establish a connection between humans

and the kami. Among these rituals were rites of

purification and offerings to the gods of rice, sake,

H ANDBOOK TO L IFE IN M EDIEVAL AND E ARLY M ODERN J APAN

356

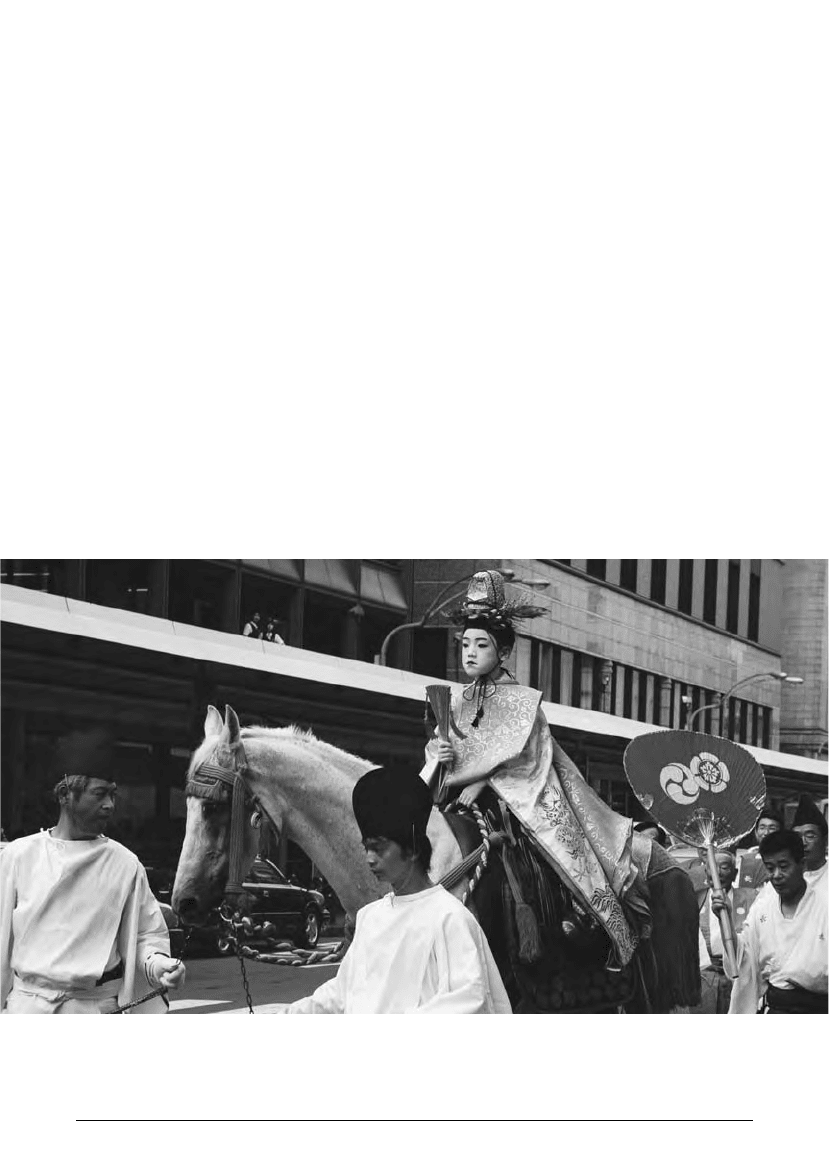

12.13 Scene of a Gion Festival parade in the streets of present-day Kyoto (Photo William E. Deal)

vegetables, and other nonmeat products emblematic

of an agricultural community. Purification, central

to Shinto conceptions of the sacred, was required of

both Shinto priests and festival participants before

they could engage in these rituals of thanksgiving

and supplication. One other common aspect of festi-

vals was a communal feast between people and the

gods.

Yearly Rituals

Yearly rituals had their origins in Buddhist and other

rites performed on a regular schedule by the imper-

ial court. Starting in the Kamakura period, however,

these rituals were diffused into the larger popula-

tion, and at least some of the rituals once performed

only at court came to be practiced more generally.

Yearly rituals were integrated into the cultural calen-

dar, so communities throughout different regions of

Japan came to observe them at similar times of year.

Over the course of the medieval and early modern

periods, the yearly ritual calendar was revised and

adapted to meet changing cultural and social needs,

reflecting the interests of warriors and other social

classes. This was especially the case in the Edo

period when merchant and artisan values informed

the kinds of rituals that were performed annually.

The following are examples of just a few of the

yearly rituals celebrated in the medieval and early

modern periods:

SETSUBUN (EVE OF THE FIRST DAY

OF SPRING)

The performance date varied from year to year

because the first day of spring was traditionally calcu-

lated using the lunar calendar. Also referred to as oni

harai (“sweeping away the demons”), Setsubun was a

ceremony in which beans were thrown both inside

and outside the house to ward off evil demons.

SHICHIGOSAN (SEVEN-FIVE-THREE)

Observed on November 15, Shichigosan was a ritual

for children at the ages of seven, five, and three. Boys

and girls of these ages were thought to be particularly

susceptible to malevolent forces, so they were taken

to a Shinto shrine to gain the blessings of the gods.

This ritual was believed to provide divine assurance

of a safe and prosperous future for children.

OBON (OR URABON-E, BON FESTIVAL)

Observed from July 13 to 15 (or from August 13 to

15 in some parts of Japan). The Bon Festival, dating

back to the seventh century in Japan but performed

prior to that in China, was a Buddhist practice in

which families honored their ancestors. Families

would welcome the souls of their ancestors back for

a three-day visit, at which time various rituals were

performed.

SHICHIYA (SEVENTH NIGHT)

This was a ritual performed on the seventh day after

a child’s birth and was associated with the gradual

fading of the 21 days of impurity that Shinto tradi-

tion associated with childbirth. It was believed that

on this seventh day it was safe to take a baby out-

doors. This ritual also included a gathering of the

extended family for the formal naming of the new-

born.

ENNICHI (DAY OF SACRED

CONNECTION)

Ennichi was a ritual where people went to a Bud-

dhist temple or Shinto shrine on a day associated

with a particular god, Buddha, or bodhisattva. For

instance, the 18th day of each month was associated

with the bodhisattva Kannon. Going to a temple on

this day ensured the practitioner of gaining a con-

nection with Kannon and receiving the bodhisattva’s

spiritual assistance. Because large numbers of people

visited temples and shrines on connection days, the

temple and shrine precincts became places where

food and other items were sold to the visiting pil-

grims. In the Edo period, this ritual often became as

much an occasion for merry-making as it was for

religious behavior.

SHOGATSU (NEW YEAR)

Observed from January 1 to 3. New Year’s celebra-

tions constituted the largest and most prominent of

E VERYDAY L IFE

357

all annual rituals. The Oshogatsu, or “Big New

Year,” celebration included family gatherings, wor-

ship at temples, and visits to the emperor’s palace

grounds. The Koshogatsu, or “Small New Year,”

took place around January 15 and was observed by

the rural populace. This ritual included a series of

events surrounding the harvest.

GA NO IWAI (OR TOSHIIWAI,

BIRTHDAY CELEBRATION)

This rite of passage marked the attainment of cer-

tain ages in the life cycle. Although this ritual had

its origins in China, the Japanese version became

established sometime in the late medieval period

and became popular in the Edo period. Of particu-

lar importance were the ages of 60, 70, 80, 88, 90,

and 99. Of these, kanreki, or “the 60th birthday,”

marked the beginning of a new life cycle according

to the 60-year Chinese lunar calendar. Usually the

person wore red to symbolize this new cycle, and

the day was celebrated by a feast with friends and

relatives.

DEATH AND DYING

Life Expectancy

In the early modern period, the Japanese had re-

markably high life expectancy rates compared with

contemporary western European populations. Al-

though life expectancy rates differed significantly

depending on factors such as geographical region

and the period of time during which samples were

collected, rates for 18th- and 19th-century Japan

ranged roughly between 35 and 45 years of age,

sometimes hovering higher than 50 for men and

women in some localities. Although these rates

may appear low when measured by current stan-

dards, they are surprisingly high for a preindustri-

alized society that endured three major famines

between the years 1732 and 1836. By way of con-

trast, it is instructive to note that at the beginning

of the 19th century, European life expectancy at

birth was around 35 to 40 years of age at the very

highest end of the scale.

Disease

Due to its relative geographical isolation and pro-

hibitions on travel into and out of the country,

Japan escaped comparatively unscathed from

many of the major epidemics that decimated the

populations of Europe. However, diseases such as

influenza, smallpox, measles, and leprosy contin-

ued to afflict the inhabitants of Japan, particularly

the poorer segments of society. In addition to peri-

odic countrywide famines, epidemics of cholera

occasionally swept through Japanese cities, and

many people suffered from the disease beriberi,

also known as the “Edo disease” due to its pre-

valence in the city of Edo. Beriberi was character-

ized by a nutritional deficiency stemming from a

diet heavily dependent on polished white rice.

Methods of dealing with sewage, although more

sanitary than those used in Europe at the time,

were nevertheless unhygienic and encouraged

numerous stomach and intestinal disorders, earn-

ing the country a reputation as a haven for

parasites. Treatments for disease traditionally

relied on Chinese medicine, though in the second

half of the Edo period, Western medicines and

medical practices began to be used in treatments as

well.

Suicide

In contrast to the opprobrium placed on suicide in

Western culture, the taking of one’s life was not a

disgraceful act in Japan. Suicide was considered an

honorable means of ending one’s life and a legiti-

mate way of dealing with inexorable conflicts or

intense social pressure. While suicide was not

accepted by all individuals within society, it repre-

sented an important aspect of a Japanese view of life

and death.

H ANDBOOK TO L IFE IN M EDIEVAL AND E ARLY M ODERN J APAN

358

The Afterlife

The Japanese believed that when people died their

spirits entered shigo no sekai, “the world after death,”

or Yomi no Kuni, “the Land of Darkness.” During

the afterlife these spirits interact with the world at

times of celebrations such as the Bon Festival and

New Year’s festivities. In addition to this view, Bud-

dhism influenced beliefs in reincarnation and the

existence of realms such as hells and the Pure Land.

These Buddhist views of death were central to life in

the medieval and early modern periods.

Cremation

Cremation (kaso) was the most common way of

treating the corpse in Japan. This process was

espoused by Buddhists, who believed that the

deceased person’s body must be disposed of quickly

in order for his or her soul to transmigrate and be

reborn. Cremation spread to Japan from China and

Korea and was practiced by the general populace in

the Kamakura and Muromachi periods. Confucian-

ism, however, advised against cremation and advo-

cated coffin burial (taiso) instead. As Confucianism

gained popularity during the Edo period, increasing

numbers of shogun and daimyo chose burial as

their preferred method of postmortem treatment,

ultimately leading to a ban on cremation for the

common people. However, following the Meiji

Restoration, cremation was reinstated in an effort to

curb the spread of certain diseases.

Mourning

In addition to being a process of emotional catharsis

or grieving, mourning (mo) was a way to deal with

the impurity one encountered in close proximity to

death. During mourning, one was secluded within

the home, not allowed to eat meat, contact Shinto

deities, or perform his or her traditional duties. The

length of this process varied depending on one’s inti-

macy with the deceased.

READING

General

Frédéric 1972: everyday life in the medieval period;

Dunn 1969: everyday life in the early modern

period; Hanley 1997: everyday life in the early mod-

ern period; Edo-Tokyo Museum (ed.) 1995: every-

day life in the early modern period in the city of

Edo

The Family

Frédéric 1972, 34–45: medieval children and child-

hood, 53–56, 60–65: the medieval family; Hanley

1997, 137–150: early modern family structure;

Dunn 1969, 165–174: early modern children and

childhood

E VERYDAY L IFE

359

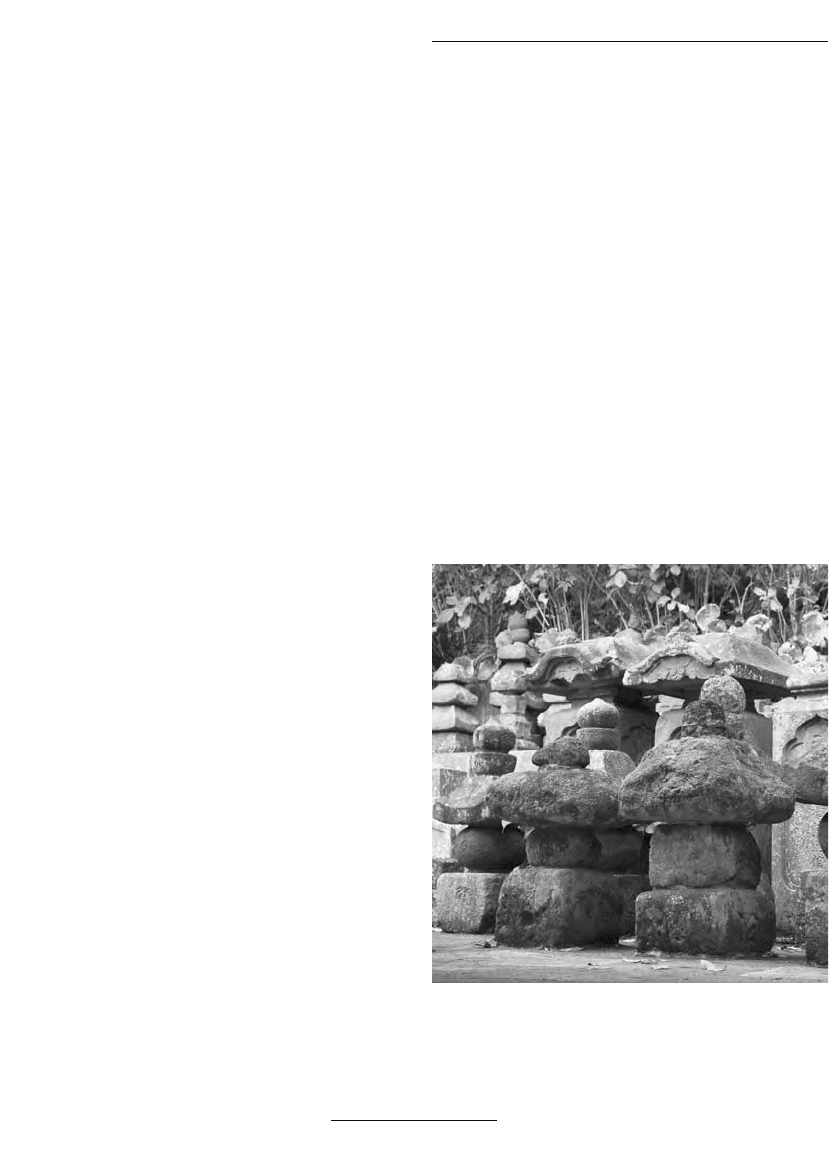

12.14 Grave markers at the Hasedera Temple in

Kamakura

(Photo William E. Deal)

The Home

Frédéric 1972, 104–112: medieval homes and fur-

nishings; Hanley 1997, 25–50, 54–63: early modern

homes and furnishings, 94–97: early modern bed-

ding; Dunn 1969, 158–160: lighting and heating

Marriage and Divorce

Frédéric 1972, 45–51: medieval marriage, 56–60;

Hanley 1997, 141–143: early modern marriage;

Dunn 1969, 173–174: marriage and divorce

Sexuality

Edo-Tokyo Museum (ed.) 1995

Pregnancy and Childbirth

Frédéric 1972, 30–34: medieval birth; Hanley 1997,

141–150: early modern family size and abortion;

Dunn 1969, 164–165: early modern childbirth

Food and Drink

Frédéric 1972, 69–77: medieval food; Hanley 1997,

63–68, 77–94: early modern food; Dunn 1969,

150–158: early modern food and cooking; Nishiyama

1997: 144–178: early modern food and restaurants

Dress and Personal

Appearance

Miner, Odagiri, and Morrell 1985: 493–501: histori-

cal clothing styles; Frédéric 1972, 77–83: medieval

dress, 83–86: medieval cosmetics, 86–88: medieval

personal hygiene; Hanley 1997, 68–73, 94–97: early

modern clothing, 97–103: early modern bathing;

104–128: early modern sanitation and personal

hygiene; Dunn 1969, 160–161: summer clothing,

161–162: personal hygiene

Sports and Diversions

May 1989

Calendar

Dunn 1969, 146–148: calendar

Miner, Odagiri, and Morrell 1985: 399–407: calen-

dar and time

Festivals and Yearly Rituals

Miner, Odagiri, and Morrell 1985: 407–414: list of

annual rituals (nenju gyoji); Brandon and Stephan

1994: New Year rituals and customs; Ashkenazi

1993: festivals (matsuri)

Death and Dying

Frédéric 2002: see specific topics; Hanley 1997,

129–137: early modern life expectancy; Frédéric

1972, 51–53: medieval death; Edo-Tokyo Museum

(ed.) 1995

H ANDBOOK TO L IFE IN M EDIEVAL AND E ARLY M ODERN J APAN

360

MUSEUMS OUTSIDE JAPAN WITH

NOTED JAPANESE ART COLLECTIONS

UNITED STATES

Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan

Museum of Art

Boston, Massachusetts: Museum of Fine Arts,

Boston

Brooklyn, New York: Brooklyn Museum of Art

Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University

Art Museums

Chicago, Illinois: Art Institute of Chicago

Cleveland, Ohio: Cleveland Museum of Art

Dallas, Texas: Trammell and Margaret Crow Col-

lection of Asian Art

Denver, Colorado: Denver Art Museum

Detroit, Michigan: Detroit Institute of Arts

Hanford, California: Ruth and Sherman Lee Insti-

tute for Japanese Art at the Clark Center

Honolulu, Hawaii: Honolulu Academy of Arts

Kansas City, Missouri: Nelson-Atkins Museum of

Art

Los Angeles, California: Los Angeles County

Museum of Art

Minneapolis, Minnesota: Minneapolis Institute of

Arts

New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Art

Gallery

New York, New York: Metropolitan Museum of

Art

Oberlin, Ohio: Allen Memorial Art Museum

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Philadelphia Museum

of Art

Portland, Oregon: Portland Art Museum

Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Art

Museum

Richmond, Virginia: Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

Salem, Massachusetts: Peabody Essex Museum

San Francisco, California: Asian Art Museum of

San Francisco

Seattle, Washington: Seattle Asian Art Museum

St. Louis, Missouri: Saint Louis Art Museum

Washington, District of Columbia: Freer Gallery

of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery (Smithson-

ian Institution)

Worcester, Massachusetts: Worcester Art Mu-

seum

C

ANADA

Montreal: Montreal Museum of Fine Arts

Toronto: Royal Ontario Museum of Archaeology

B

ELGIUM

Brussels: Musées Royaux d’Art et d’Histoire

F

RANCE

Paris: Musée National des Arts Asiatiques-Guimet

G

ERMANY

Berlin: Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst

Cologne: Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst, Köln

I

TALY

Genoa: Museo d’Arte Orientate “Edoardo Chios-

sone”

M USEUMS O UTSIDE J APAN WITH N OTED J APANESE A RT C OLLECTIONS

361

NETHERLANDS

Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum Amsterdam

S

WITZERLAND

Geneva: Bair Collection

U

NITED KINGDOM

London: British Museum

London: Victoria and Albert Museum

Norwich: Sainsbury Institute for the Study of

Japanese Arts and Cultures

Oxford: Ashmolean Museum

H ANDBOOK TO L IFE IN M EDIEVAL AND E ARLY M ODERN J APAN

362

BIBLIOGRAPHY

B

IBLIOGRAPHY

363

Addiss, Stephen. The Art of Zen. New York: Abrams,

1989.

———. How to Look at Japanese Art. New York:

Abrams, 1996.

Adolphson, Mikael S. The Gates of Power: Monks,

Courtiers, and Warriors in Premodern Japan. Hon-

olulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2000.

Akiyama, Terukazu. Japanese Painting. Geneva:

Skira, 1961.

Anderson, Jennifer L. An Introduction to Japanese Tea

Ritual. Albany: State University of New York

Press, 1991.

Anesaki, Masaharu. Nichiren, the Buddhist Prophet.

Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press,

1916.

Arai, Hakuseki. Told Round a Brushwood Fire: The

Autobiography of Arai Hakuseki. Translated by

Joyce Ackroyd. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton Uni-

versity Press, 1980.

Araki, James T. The Ballad-Drama of Medieval Japan.

Berkeley: University of California Press, 1964.

Arnesen, Peter Judd. The Medieval Japanese Daimyo:

The Ouchi Family’s Rule of Suo and Nagato. New

Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1979.

Arnott, Peter. The Theatres of Japan. London: Mac-

millan, 1969.

Ascher, Marcia. Mathematics Elsewhere: An Explo-

ration of Ideas Across Cultures. Princeton, N.J.:

Princeton University Press, 2002.

Ashkenazi, Michael. Matsuri: Festivals of a Japanese

Town. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press,

1993.

Association of Japanese Geographers, eds. Geography

of Japan. Tokyo: Teikoku Shoin, 1980.

Avitabile, Gunhild. Early Masters: Ukiyo-e Prints and

Paintings from 1680 to 1750. New York: Japan

Society, 1991.

Baird, Merrily. Symbols of Japan: Thematic Motifs in

Art and Design. New York: Rizzoli, 2001.

Barnet, Sylvan, and William Burto. Zen Ink Paint-

ings. New York: Kodansha International, 1982.

Bartholomew, James R. The Formation of Science in

Japan: Building a Research Tradition. New Haven,

Conn.: Yale University Press, 1989.

Beard, Mary Ritter. The Force of Women in Japanese

History. Washington, D.C.: Public Affairs Press,

1953.

Beasley, W. G. The Japanese Experience: A Short His-

tory of Japan. Berkeley: University of California

Press, 1999.

Bellah, Robert N. Tokugawa Religion: The Values of

Pre-Industrial Japan. Glencoe, Ill.: Free Press,

1957.

Bernstein, Gail Lee, ed. Recreating Japanese Women,

1600–1945. Berkeley: University of California

Press, 1991.

Berry, Mary Elizabeth. The Culture of Civil War in

Kyoto. Berkeley: University of California Press,

1994.

———. Hideyoshi. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Uni-

versity Press, 1982.

Bielefeldt, Carl. Dogen’s Manuals of Zen Meditation.

Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988.

Bingham, Marjorie Wall, and Susan Hill Gross.

Women in Japan: From Ancient Times to the Present.

Edited by Janet Donaldson. St. Louis Park,

Minn.: Glenhurst Publications, 1987.

Bix, Herbert P. Peasant Protest in Japan, 1590–1884.

New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1986.