Deal W.E. Handbook To Life In Medieval And Early Modern Japan

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

shrine grounds. As an architectural form, the torii is

a simple structure with two vertical posts sur-

mounted by a single or double lintel that extend

beyond the space framed by the posts.

There is debate over the origin of the torii, with

some theories favoring the view that this design ele-

ment was imported from non-Japanese architectural

forms found, depending on the particular theory, in

China or Korea, or even as far away as India. Other

theories argue that the torii is a Japanese invention.

Regardless of its origins, historical records suggest

that the torii was in use in Japan by the 10th century

and possibly before. There are many different styles

of torii, but the basic shape is similar from style to

style.

main sanctuary (honden) The main sanctuary

(sometimes called shoden), located behind other

shrine buildings, was where a kami was enshrined.

It was the most sacred area of a shrine precinct.

Only a Shinto priest was allowed into this part

of the shrine. Unlike Buddhist temples where

it was usual to find a sculptural representation of

a Buddha or bodhisattva, Shinto shrines only

rarely utilized such images. Rather, the kami was

symbolically represented by a sacred mirror, an

H ANDBOOK TO L IFE IN M EDIEVAL AND E ARLY M ODERN J APAN

314

10.3 Example of a Shinto shrine gate (torii) (Photo William E. Deal)

idea derived from Japan’s early mythology. The

style of the main sanctuary was usually considered

the defining architectural feature of a shrine

complex.

worship hall (haiden) A worship hall was central to

the plan of a Shinto shrine. Some shrine precincts,

such as those located in the mountains, only had a

worship hall because the entire mountainous site

was considered the abode of the kami and therefore

a special sanctuary (honden) in which to enshrine the

deity was not needed.

ritual dance hall (maidono) Ritual music and

dance has always been associated with Shinto religious

ceremonies (see chapter 9: Performing Arts). As a

result, some shrine complexes included a separate hall

set aside for such ritual performances. Prior to the

medieval period, temporary stages were used for ritual

music and dance, but by the Kamakura period, perma-

nent structures were built for this purpose.

offering hall (heiden) A shrine offering hall was

used to make offerings to the kami and to recite

prayers. These offerings (known as gohei or heihaku)

were typically made of white paper, silk, or cloth.

ceremonial kitchen (shinsenden) Usually only

found at larger shrines, the ceremonial kitchen was

the place where food offerings were prepared for rit-

ual use.

Domestic Architecture

In the 16th and early 17th centuries, two new build-

ing styles arose that were closely connected to the

interests and concerns of the warrior class: the castle

and the shoin-style residence.

CASTLES

The Japanese castle, an indigenous architectural

form, was the product of only about 100 years of

construction, roughly 1530–1630. This corresponds

to a time in which struggles to unify Japan were

begun by powerful military lords and finally accom-

plished by the Tokugawa shogunate. Oda Nobu-

naga, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, and Tokugawa Ieyasu

were among those powerful lords who built large-

scale and elaborate castles. Although there were

precedents for Japanese castles in the Kamakura and

Muromachi periods, these were designed and used

almost solely as military fortifications. The castle

form discussed here came to serve a number of dif-

ferent purposes that went well beyond strategic

defense.

Castles served military, political, domestic, sym-

bolic, cultural, and other functions. The castle

served as a military garrison for troops and arms,

and a fortress from which to defend oneself from

attack. Besides this overt military purpose, the castle

was also home to the castle’s lord, his family, and his

closest retainers. As such, it was the place where the

lord received his retainers and conducted much of

his business. Within the direct vicinity of the castle,

castle towns (jokamachi; see chapter 2: Land, Envi-

ronment, and Population) developed as both eco-

nomic and administrative centers of the region.

Thus, a castle and its town was the political center of

domain power and influence.

Castles were imposing structures that required

significant wealth to build, run, and maintain. The

bigger the castle and castle grounds, and the higher

the main tower, the more prestige was conveyed.

Castles served, therefore, as powerful reminders of

the military and political might of the resident lord.

They also served as the location for cultural and

other leisure pursuits that projected the image of the

refined lord conversant with aesthetic pursuits. To

this end, warriors patronized the arts and commis-

sioned artists to create works for their castles. For

instance, Oda Nobunaga brought the famous

painter Kano Eitoku (see above) to Azuchi Castle to

produce wall and screen paintings with landscape

and other motifs.

Castle construction peaked between 1600, when

Tokugawa Ieyasu defeated the Toyotomi at the Bat-

tle of Sekigahara, and 1615, when the remaining

Toyotomi forces were routed at the siege of Osaka

Castle. After 1615, the Tokugawa shogunate limited

to one the number of castles that could be built in

each domain. This attempt to secure political and

military control over Japan led, in 1620, to a com-

plete ban on castle construction. Thus, the architec-

A RT AND A RCHITECTURE

315

tural style and design of castles spanned barely 100

years before it was ended by this edict.

Over time, castles were built, destroyed, and

rebuilt. They changed ownership, sometimes fre-

quently, and with each change of lord usually came

additions or other changes to the castle that, among

other things, asserted the power of the current

inhabitant. The following is a very partial list of cas-

tles, and the lord or lords most closely or famously

associated with them, along with locations and the

year in which their principal construction occurred

or was completed.

Castle Design

There are few extant castles existing in their origi-

nal form. One exception is Himeji Castle, also

known as the White Egret Castle (shirasagijo) be-

cause of its white-walled design. Castles like Himeji

were built with many levels to present an imposing

image and to afford a view of the lord’s domain. In

1581, after defeating a rival lord in battle, Toyotomi

Hideyoshi constructed a three-storied castle tower

(tenshu) on the defeated lord’s land. This was the

beginning of Himeji Castle. The site was not fully

developed as a castle until 1601 when Tokugawa

Ieyasu gave the site to Ikeda Terumasa (1564–1613),

his son-in-law. Terumasa constructed Himeji Cas-

tle, completing work in 1609. The structure and

design of Himeji Castle is indicative of late me-

dieval and early Edo-period castle architecture. The

following description of some of the more impor-

tant architectural features of castles is generic but

makes special reference to Himeji Castle where

illustrative.

C

ASTLE SITE

Historically, there were three main castle types

according to geographic location: 1) castles built in

mountains (yamajiro), 2) castles built on plains

(hirajiro), and 3) castles built on a hill or low moun-

tain surrounded by a plain (hirayamajiro). Himeji

Castle is an example of this last type of castle.

These varied castle sites had different strategic

strengths and weaknesses. In general, the lower the

elevation of a castle, the more fortifications it

required.

M

AIN TOWER (

TENSHU)

A castle’s main—and usually multistoried—tower

(tenshu or tenshukaku) was sited at the center of the

H ANDBOOK TO L IFE IN M EDIEVAL AND E ARLY M ODERN J APAN

316

Castle Principal Lord(s) Location Principal

Construction

Date

Inuyama Castle Oda Nobuyasu Inuyama 1537

(Aichi Prefecture)

Azuchi Castle Oda Nobunaga Mt. Azuchi (on Lake Biwa) 1576–1579

Himeji Castle Toyotomi Hideyoshi Himeji 1581

Ikeda Terumasa (Hyogo Prefecture) 1601–1609

Osaka Castle Toyotomi Hideyoshi Osaka 1583

Matsumoto Castle Ishikawa Kazumasa Matsumoto 1590

(Nagano Prefecture)

Fushimi Castle Toyotomi Hideyoshi Momoyama district, Kyoto 1594

Okayama Castle Ukita Hideie Okayama 1597

Ikeda Tadatsugu 1603

Edo Castle Tokugawa Ieyasu Edo 1603 (begun)

Hikone Castle Ii Naomasa Hikone 1603

(Shiga Prefecture)

Nijo Castle Tokugawa Ieyasu Kyoto 1603

Nagoya Castle Tokugawa Ieyasu Nagoya 1612

castle complex (hommaru) at the highest location in

the castle grounds. This placement provided both a

strategic view of the adjoining area and an imposing

symbol of the castle lord’s power. The term tenshu,

or main tower, is often translated into English as

“donjon,” a word used to describe a medieval Euro-

pean castle’s inner tower.

There were four major types of main towers:

• single tower

• compound tower: a main tower that included

attached secondary buildings or towers

• linked tower: a main tower connected by a pas-

sageway to a secondary tower or other structure

• connected tower: a main tower connected by

passageways to multiple secondary towers

There were also castles constructed that employed

variations on these four major tower types by com-

bining features of more than one tower style. Himeji

Castle is an example of a connected tower construc-

tion style. In addition to the main tower, there were

additional small towers (yagura) with a design simi-

lar to the main tower. These small towers were used

for different purposes, including as guard towers and

as weapons storage.

I

NNER CITADEL (HOMMARU)

The focal point of castle design was the inner citadel

called the hommaru. It was within this central en-

closure that the main tower was sited. Additional

compounds, arranged in different configurations

A RT AND A RCHITECTURE

317

10.4 Main tower (tenshu) of Himeji Castle (Photo William E. Deal)

depending on the castle and the physical space it

occupied, enclosed this central space, spiraling out

in many instances in a circular fashion from the cen-

ter. These compounds bore names such as ni-no-

maru (“second circle”) and san-no-maru (“third

circle”). The lord’s business was conducted in the

inner citadel, but the family residence was located in

one of the secondary compounds.

There was a strategic function to these multiple

compounds. The fact that castles had different ar-

rangements meant that the enemy could not be

sure how to quickly and effectively reach the inner

citadel. At Himeji Castle, for instance, the com-

pounds were laid out in interlocking sections. In

order to successfully breach the castle, enemy

attackers would have had to traverse open areas

within compounds and charge along paths that had

no obvious logic to them. They would also have had

to deal with multiple gates and towers from which

they would surely have been fired upon.

M

OATS (HORI)

Castle designers utilized water-filled moats to deter

invaders from successfully breaching the castle

grounds. Himeji Castle used such a defensive system.

S

TONE FOUNDATION WALLS (ISHIGAKI)

Even if an attacking army were able to cross the

moats, they would be met with steep stone founda-

tion walls that were designed not only for their struc-

tural use as retaining walls but also to be difficult to

climb. To this end, foundation walls were typically

constructed so that they rose steeply from the base

and were curved somewhat outward at the top.

C

ASTLE GATES

For an invader the easiest way into the castle was

through one of the castle gates. There usually

existed both a main gate in front (otemon) and also a

rear entrance gate (karametemon). Secondary gates

also were used. Gates, however, did not lead directly

into the main part of the castle grounds. Rather,

they were designed so that the path to the castle’s

interior included zigzags, additional gates, dead

ends, and other mazelike methods for confusing

anyone not already familiar with the castle plan.

Interior gates sometimes included a two-story gate-

house that could be used to further defend against

entry into the heart of the castle.

W

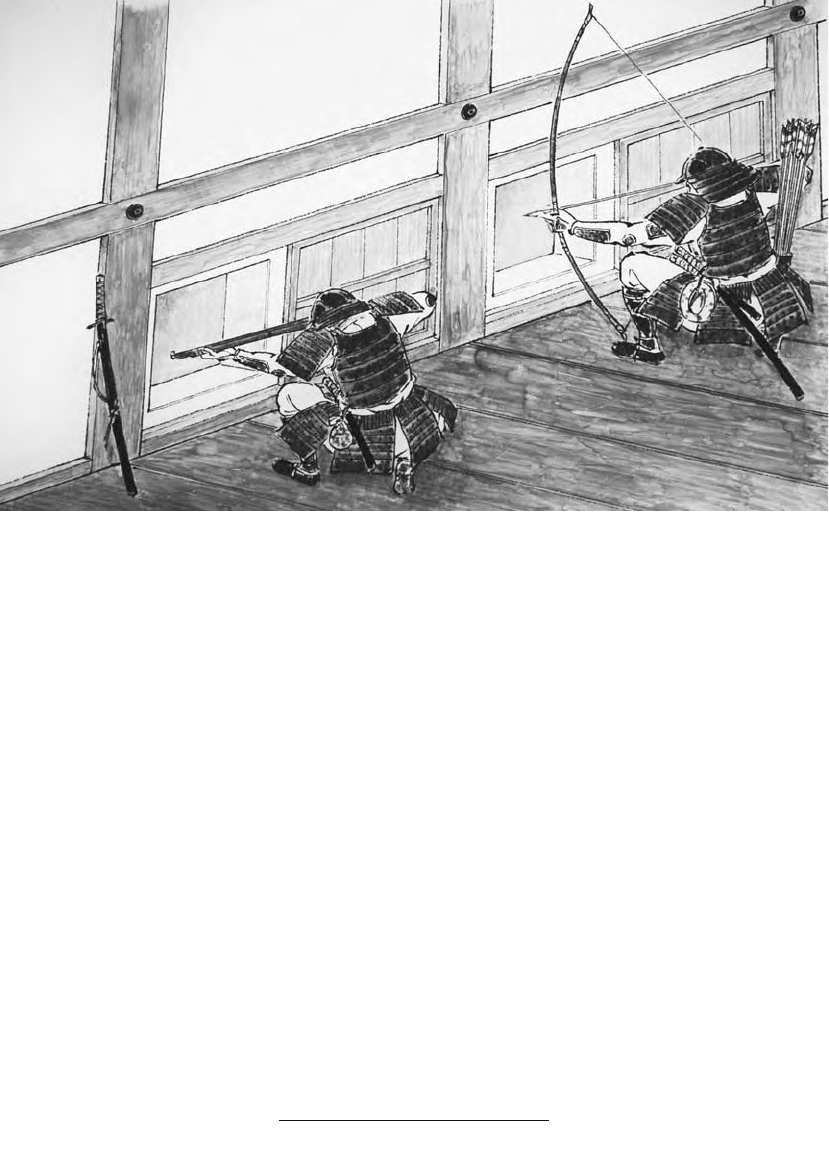

EAPON PORTALS (SAMA)

Weapon portals, often called “loopholes” in English,

were openings in walls and floors through which an

arrow could be shot or a musket fired at the enemy.

These openings could be round, square, or triangu-

lar in shape. This was another of a castle’s defenses.

Portals for archers were call yazama (arrow portals)

and those for muskets were termed teppozama (mus-

ket portals). Besides accommodating these weapons,

portals had a narrower openings onto the outside

surface and wider openings on the inside surface.

This design allowed castle warriors room to maneu-

ver their weapons while providing only a very lim-

ited access target for enemy arrows and bullets.

H ANDBOOK TO L IFE IN M EDIEVAL AND E ARLY M ODERN J APAN

318

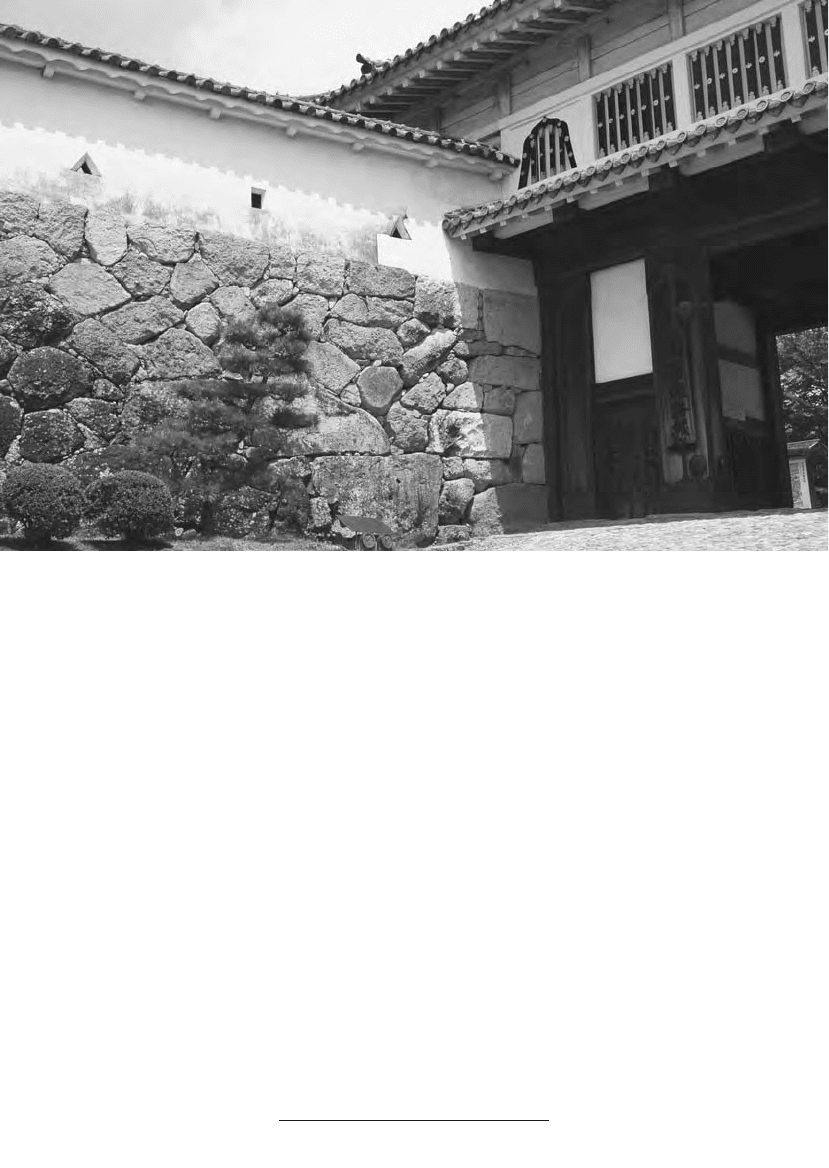

10.5 Steep wall of the main tower (tenshu) at Himeji

Castle

(Photo William E. Deal)

SHOIN-STYLE WARRIOR RESIDENCES

In addition to castle construction, the development

of the Shoin (writing hall) style (shoin-zukuri) resi-

dence was the second major architectural innova-

tion that occurred in the late medieval and the

beginning of the early modern period. The Shoin

style traces its origins in part to the aristocratic

Shinden residential style (shinden-zukuri) prevalent

in the Heian period and adapted to warrior tastes

in the medieval period. Though elements of Shoin-

style design were used in commoners’ dwellings

later in the Edo period, it was this form of architec-

ture that was particularly associated with the war-

rior class by the beginning of the early modern

period.

In addition to the functionality of the Shoin style,

there was an important political aspect to this

architectural design element that expressed the

social hierarchy explicit between lord and retainer.

The reception room in a Shoin-style structure was

where, for instance, a lord would receive his retain-

ers. The placement of people within this space—

lord seated on the upper of two floor levels and

retainers on the lower—expressed a clear power dif-

ferential between the two.

Beginning in the 14th century, Shoin-style archi-

tectural details began appearing in the private quar-

ters of Zen monasteries, especially the temple

residences of abbots and other high-ranking monas-

tics. Buddhist abbots, for instance, utilized rooms

that included a writing desk, a feature that became

central to the Shoin style. An important prototypical

example of the architectural style that developed

into the Shoin style is the extant Dojinsai, a tea cer-

emony room at the Togudo, a hall that is part of the

Ginkakuji temple complex in Kyoto.

A RT AND A RCHITECTURE

319

10.6 Wall and gate at Himeji Castle (Photo William E. Deal)

By the Azuchi-Momoyama period, the design

elements characteristic of the Shoin style were for-

malized. These new and newly elaborated features

included an alcove for the display of important

hanging scrolls (or for wall paintings), a set of stag-

gered shelves for treasured objects in the military

lord’s collection, and a floor of grass mats with a

place of honor reserved for the highest-ranking

individual. Shoin-style architecture also included a

built-in desk in the alcove. This feature of the room

was utilitarian, but it also provided a way of showing

that the lord was a person of culture. These are the

same features used today in the formal rooms of

contemporary Japanese homes.

Shoin-Style Design Elements

Buildings incorporating the Shoin style contain

rooms, such as a formal reception room (zashiki),

that utilize at least some of the following distinctive

design elements:

D

ECORATIVE ALCOVE (TOKONOMA)

The decorative alcove, known as a tokonoma, was a

raised floor that created a niche built into a back

wall. It was used for displaying such things as a

prized object, a flower arrangement, or a hanging

scroll (kakejiku).

S

TAGGERED SHELVES (CHIGAIDANA)

Staggered shelves were usually two shelves set at dif-

ferent levels. Unlike the formality of the tokonoma,

H ANDBOOK TO L IFE IN M EDIEVAL AND E ARLY M ODERN J APAN

320

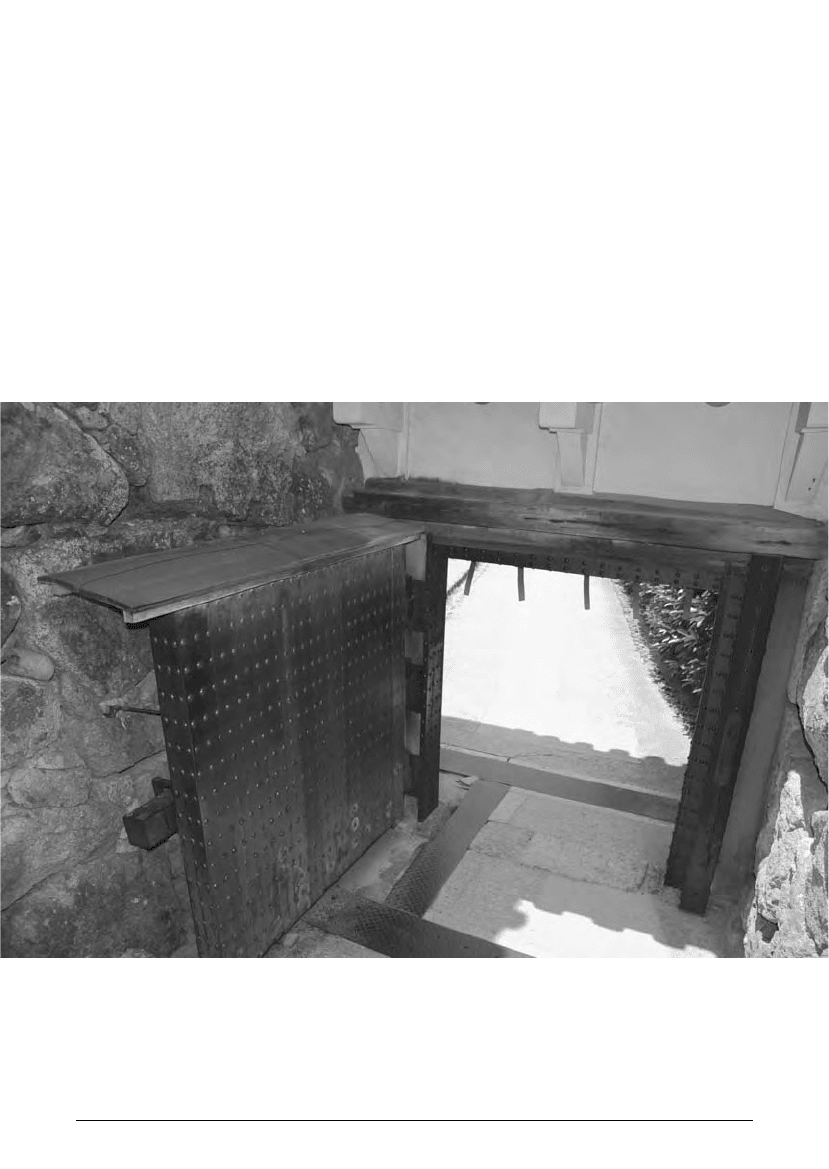

10.7 The Ho Gate of Himeji Castle leads to the entrance of the First Water Gate, which is the most direct route to the

main tower (tenshu). One of many gates that soldiers would encounter en route to the castle, these fortifications were

designed to confuse as well as to protect. The iron plating on the gate door provided additional means of defense.

(Photo

William E. Deal)

the chigaidana were sometimes used for keeping per-

sonal items. In the dwelling of a wealthier person,

the staggered shelves might also have a decorative

purpose.

B

UILT-IN DESK (TSUKESHOIN)

The Shoin style derives its name from the built-in

desk (tsukeshoin) that was situated next to the

tokonoma. The built-in desk faced toward the outside

of the building and used four small sliding paper

screens (shoji; see below) for the window between

interior and exterior.

D

ECORATIVE DOOR (CHODAIGAMAE)

The decorative door of a Shoin-style room, located

to the viewer’s right of the tokonoma, originally led to

a bedroom or other space. As this style developed,

however, it sometimes became a purely ornamental

design feature. The door consisted of four painted

sliding panels.

T

ATAMI MAT

Tatami mats are a floor covering made of a straw

base and a surface of tightly woven grass. Class dis-

tinctions were evident from the thickness and pat-

tern of mats. Individual mats were rectangular and

of varying sizes depending on region. The number

of mats that fit into a room came to be the standard

measure of a room’s size.

S

LIDING DOOR (FUSUMA)

Sliding doors known as fusuma were used to create

partitions between interior spaces. The fusuma is

made by pasting paper or silk on a thin wood-lat-

ticed frame. Sliding doors were often adorned with

monochrome ink paintings, decorative composi-

tions, and other designs.

S

CREEN PARTITIONS (SHOJI)

Similar to fusuma, screens (shoji) were used to create

partitions between inside and outside, or between

A RT AND A RCHITECTURE

321

10.8 Warriors firing from castle weapon portals (Himeji Castle exhibit; Photo William E. Deal)

interior spaces. Both fixed and sliding partitions

were used as either windows or doors. Shoji also used

a lattice-work frame, but the paper pasted on to

cover the frame was a translucent white. This cre-

ated a more diffused lighting effect where it was

used.

T

RANSOM (RAMMA)

A ramma, or transom, was a fitted into a rectangular

space located between a sliding door (fusuma) and

the ceiling of a room. Made of wood, ramma were

carved or painted with various designs and themes.

Functionally, ramma provided a room with light and

air circulation.

E

XTERIOR SLIDING DOOR (AMADO)

Amado are exterior wooden sliding door panels used

to separate the interior and exterior spaces of a

building. These heavy panels were used at night or

as protection during bad weather.

H ANDBOOK TO L IFE IN M EDIEVAL AND E ARLY M ODERN J APAN

322

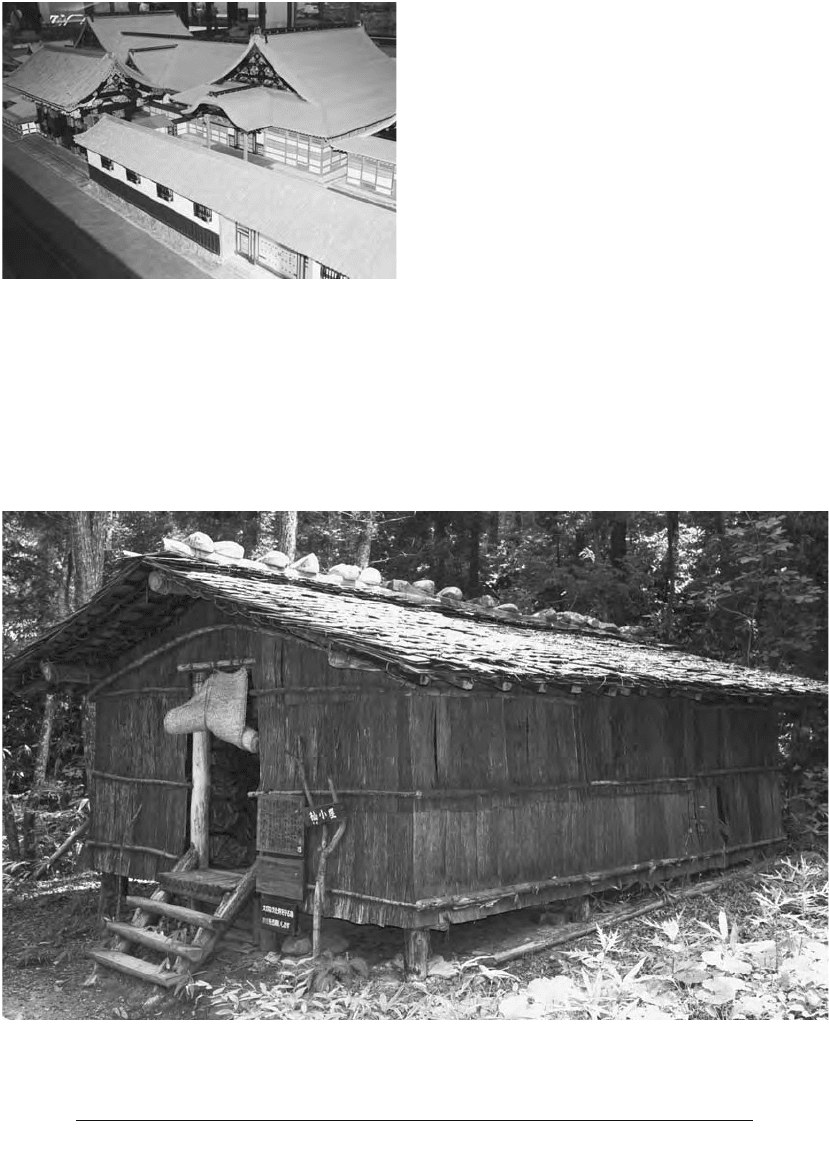

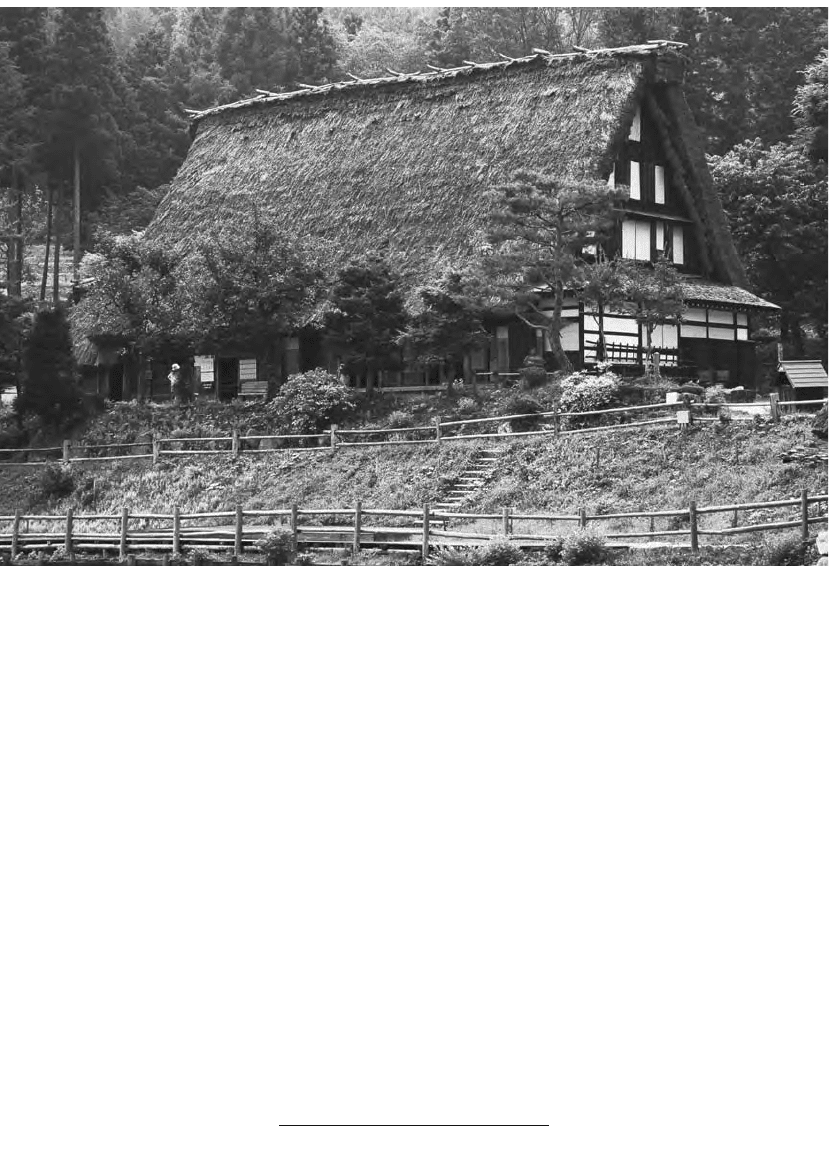

10.10 Example of an Edo-period woodcutter’s house (Photo William E. Deal)

10.9 Model of the Edo residence of the domain lord

(daimyo) Matsudaira Tadamasa (1597–1645), who

headed the Fukui domain (han). This residence, in the

Shoin style, burned to the ground in the Meireki Fire

(1657). Thereafter, such luxurious compounds were no

longer constructed.

(Edo-Tokyo Museum exhibit; Photo

William E. Deal)

COMMONER RESIDENCES

The term minka, or “folk dwellings,” is a generic

term used to describe the residences of commoners

that existed prior to the Meiji Restoration in 1868.

By the early modern period, there were many differ-

ent types of housing depending on region, weather,

and other factors such as the social class and wealth

of the resident. Despite this variety, commoner resi-

dences can be divided into two major categories:

rural dwellings and urban dwellings. Rural dwellings

included farmhouses (noka), fishermen’s houses

(gyoka), and mountain houses (sanka). Urban dwel-

lings included townhouses (machiya).

In the early modern period, blending of residen-

tial styles also occurred. For instance, by the middle

of the Edo period, Shoin-style architectural details,

originally a feature of warrior dwellings, started

being utilized in the design and construction of com-

moner homes. Thus, sitting rooms (zashiki), used in

warrior residences as a place to receive vassals,

became a detail in the homes of wealthy commoners.

The Tokugawa shogunate, however, tried to control

such architectural style–blending in order to main-

tain distinct boundaries between social classes.

Rural dwellings used regional design styles and

architectural elements, as well as regional building

materials. Generally, though, rural dwellings were

constructed of wood. A house would have a packed-

earth floor (doma) space used for cooking and other

such tasks, and a raised-timber floor space used as

living quarters. Urban dwellings followed a similar

design, but tended to be smaller than their rural

counterparts as a result of the differences in available

space between city and countryside. Machiya often

consisted of two stories. These dwellings might also

A RT AND A RCHITECTURE

323

10.11 Example of an Edo-period farmhouse (Photo William E. Deal)