Deal W.E. Handbook To Life In Medieval And Early Modern Japan

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

both concepts integral to later tea aesthetics. So fig-

ural were these terms that the understated aesthetics

of Murata Shuko, and his heirs Takeno Joo and Sen

no Rikyu, became known as wabi tea to distinguish

them from more ostentatious tea preparations

favored by the feudal lords.

In addition to contributing to a philosophy of

tea, Shuko also influenced tea architecture through

his service to Ashikaga Yoshimasa. At the eastern

Kyoto villa today known as Ginkakuji, Shuko hosted

tea gatherings on behalf of Yoshimasa that took

place in a room designed with only four and a half

tatami mats. These mats consisted of woven grass

covering a thick filling of rice straw. The configura-

tion and number of tatami used by Shuko in this

intimate tea setting later became a standard format

for tearooms.

Sen no Rikyu (1522–91) formalized tea ideals

first articulated by Murata Shuko. However, Rikyu

was more influential than Shuko both in terms of

access to prominent tea patrons and adherence to

tea sensibilities that typified Zen austerity and

understatement. During his merchant upbringing in

the prosperous port city of Sakai on the eastern

Inland Sea, Rikyu was exposed to continental

imports such as tea ceramics that appealed to

wealthy Sakai merchants, whose patronage and cul-

tural aspirations fueled new currents in tea aesthetics

from the late Muromachi era to the 17th century.

Further, Rikyu studied with Takeno Joo (1502–55), a

Sakai-based Zen priest, poet, and tea aficionado who

first followed the teachings of his teacher, Shuko,

and then strove to improve upon them later in his

career. Joo eventually exercised considerable influ-

ence, for he possessed a sizable and enviable collec-

tion of tea utensils, and his innovations were carried

as far as Kyoto.

Rikyu, a student of Joo, grew to prominence in

this environment, where he was particularly note-

worthy for his pursuit of the wabi aesthetic. Rikyu

followed both of his predecessors in the way of tea,

as he too harbored a profound appreciation of

wabi—purity and harmony expressed in the humble

appearance of the rustic tearoom and related tea

objects, as well as the uncomplicated allure of aus-

terity and restraint. As noted earlier, wabi has been

an especially figural sensibility in tea culture,

although it is somewhat incomplete unless paired

with its aesthetic complement, sabi, which evokes

the loneliness and quietude of age, as well as the nat-

ural tarnish and worn surfaces that can be acquired

only through time and frequent use.

As Oda Nobunaga (1534–82) ascended to power

in the late 1560s, he summoned Rikyu to serve as

his tea officer and cultural adviser. After Nobuna-

ga’s assassination in 1582, Toyotomi Hideyoshi

followed his former general both in unifying Japan

and engaging Rikyu. Both Nobunaga and Hide-

yoshi recognized the importance of tea and re-

lated arts in military culture and enjoyed the

heightened political and cultural supremacy Rikyu

conferred through his status as highest authority of

the wabi tea tradition. Although officially a cultural

adviser, Rikyu could serve as social agent, go-

between, or even diplomat, thus intervening in var-

ious delicate political contexts even while reflecting

favorably upon the cultural acumen of his overlord.

Further, Nobunaga and Hideyoshi had acquired

coveted tea implements originating in the Ashikaga

collections. Armed with the bounty of their con-

quests, these military lords demonstrated to con-

quered daimyo tea enthusiasts that they had

supplanted the old regime, yet appreciated its cul-

tural heritage.

Soon after achieving his goal of unifying Japan,

Hideyoshi ordered Rikyu to commit seppuku, or rit-

ual suicide, in 1591 for reasons that remain unclear.

Despite his demise, aspects of Rikyu’s taste and

ideals persisted in tea practice amid the sweeping

cultural changes of the Edo period.

Tea rituals became less exclusive and tea masters

grew more accessible as Rikyu’s grandson, Sen Sotan

(1578–1658) and his three heirs, Soshitsu (1622–97),

Sosa (1619–72), and Soshu (1593–1675), founded

schools and established publications to disseminate

tea traditions. Initially, daimyo patronage domi-

nated, but later adherents grew to include samurai,

artisans, merchants, and other commoners. Some of

Rikyu’s innovations helped to further the broad

access to tea that characterized the Edo period. For

example, in a break with prior protocol, Rikyu had

stipulated that tea should be made in front of guests,

rather than prepared in one room and later served in

another. Practices such as this fostered the egalitar-

ian image of tea projected by Rikyu descendants

who formed the Urasenke school, a tradition aimed

H ANDBOOK TO L IFE IN M EDIEVAL AND E ARLY M ODERN J APAN

304

at attracting more humble members of society to tea

practice. The ascetic spirituality of medieval Bud-

dhism that suffused the wabi style of tea most closely

connected with Rikyu began to fade as tea patronage

shifted from wealthy merchants and ambitious mili-

tary lords to peacetime samurai who favored a style

sometimes described as “daimyo tea.”

Despite his significant political and spiritual con-

tributions, Rikyu most affected tea and related arts

through his exacting connoisseurship—enabling

him to identify tea utensils that embodied his ideals

of restraint, simplicity, and directness. Although

Rikyu’s greatest legacy may be his exquisite sense of

design and discernment, subsequent generations

have credited him with numerous other achieve-

ments. Principles of tea ascribed to Rikyu codified

by his great-grandsons in the Edo period propose

that he established the four ideals of tea captured in

the Japanese characters wa (harmony), kei (respect),

sei (purity), and jaku (tranquility or natural ele-

gance). Below, these concepts are presented in terms

of the role and relevance of each term in the world

of tea ritual.

harmony (wa): a desire for reciprocity, both at the

tea gathering and in the outside world

respect (kei): awareness of one’s individual role and

responsibilities, and appropriate decorum

purity (sei): a commitment to preserve social and

spiritual integrity

tranquillity or natural elegance (jaku): savoring the

transient moment to gain renewal

Tea Preparations

The host’s procedure for preparing tea (temae)

demonstrates both economy of motion and grace.

Each action flows into the next in a measured, seam-

less choreography interrupted only by periodic taps

and flourishes that punctuate stages of preparation.

Typically, the temae involves six basic steps:

1. All tea implements, except the iron water kettle,

which is usually placed on the hearth or brazier

before the guests enter, are carried into the tea-

room and arranged.

2. The host purifies the tea container (natsume or

chaire) and bamboo tea scoop (chashaku) by wip-

ing them with a silken cloth (fukusa).

3. Hot water poured into the tea bowl (chawan)

warms both the bowl and bamboo tea whisk

(chasen).

4. Using the bamboo tea scoop, the host places

powdered green tea in the bowl. Hot water is

added to the tea and whisked until the texture is

frothy.

5. After guests have enjoyed their tea, the bowl and

whisk are cleaned along with the tea scoop.

6. The host withdraws from the tearoom, returning

all implements except the kettle to the prepara-

tion room.

Typical tea gatherings conclude as the host passes

tea utensils for guests to appreciate and inspect. Ful-

filled by the tea and atmosphere of camaraderie,

guests leave the gathering refreshed by their shared

experience.

Tea Utensils (chadogu)

Hanging Scroll (jiku) When entering the tea-

room, guests should approach and honor the

scroll first, by bowing. Unlike many of the imple-

ments, the scroll is not part of the process of

preparing tea. Still, the jiku is essential to the tea

gathering, and may be the most revered object in

the tearoom. Scrolls may feature painted images,

although calligraphic works are also favored.

Mounted on backings made of textiles attached to

a dowel to facilitate storage, jiku are placed in the

tokonoma, an alcove reserved for displaying scrolls,

flower arrangements, and sometimes an incense

container. Scrolls are also known as kakejiku or

kakemono.

Flower Container (hanaire) Flowers for tea are

arranged to appear as if still growing in the fields.

The flower container, or hanaire, is selected to suit

the buds, blossoms, and/or grasses, to harmonize

with seasonal themes, and to complement the tea-

room itself. Hanaire may be bronze, copper,

ceramic, or bamboo.

A RT AND A RCHITECTURE

305

Tea Kettle (kama) The kama comes in many sizes

and shapes. Larger kettles are placed on the ro (fire-

place or hearth) and smaller versions are placed on

the furo (brazier). In chanoyu, the kettle is used to

boil water, not to steep tea, as in many other coun-

tries. There are many shapes of kettles, and although

they are usually made of iron, kama are also crafted

from gold or silver.

Portable Brazier (furo) The furo is a portable bra-

zier that is used for ceremonies from May to Octo-

ber. Furo are made of earthenware, bronze, iron,

wood, and other ceramic materials. During the win-

ter, the tea kettle is heated on the fireplace or hearth

(ro) itself. An iron furo is always placed on the shiki-

gawara (fire tile).

Fresh Water Jar (mizusashi) This covered jar

holds cool water used to regulate the temperature of

the water in the kama or to rinse certain utensils.

While mizusashi are ceramic, wooden or metal jars

are also used.

Tea Caddy (chaire and natsume) The chaire is

a type of tea caddy used for thick tea and the nat-

sume is used for thin tea. Chaire are kept in shifuku

(small silk bags). A chaire is usually ceramic and has

an ivory lid. Natsume may also be called usuki or

chaki.

Tea Scoop (chashaku) Crafted from various mate-

rials ranging from ivory to bamboo, the chashaku is

used for scooping powdered tea from the caddy into

a tea bowl.

Teabowl (chawan) The teabowl plays a central role

in the art of chanoyu as the link between host and

guest. Made in a wide variety of sizes, shapes, and

types, chawan are selected by the host to express the

degree of formality of the occasion, seasonal prefer-

ences, and contemporary sensibilities.

Lid Rest (futaoki) for the Tea Kettle and Water

Ladle There are seven kinds of famous futaoki

selected by noted tea master Sen no Rikyu (1521–

91). Each has its own specific rule for use. In gen-

eral, however, the most common futaoki is a small

bamboo mat.

Bowl for Waste Water (kensui) Water used to

rinse utensils is discarded in this bowl. Kensui are

sometimes called koboshi.

Water Ladle (hishaku) There are many types of

hishaku, defined by the cut of their handles. Those

that have handles cut from the outside diagonally

may only be used with a ro (winter tea). Those with a

handle cut from the inside diagonally may be used

with the furo (summer chanoyu).

Bamboo Whisk (chasen) Chasen are made of dif-

ferent types of bamboo. Some examples of materials

used to make tea whisks include smoked and dried

bamboo. Participants from different schools of tea

prefer certain types of tea whisks.

Tea Cloth (chakin) This piece of linen—used to

wipe tea bowls—measures about a foot long and five

inches wide.

Role of Nature in the

World of Tea

Chanoyu involves both social and religious princi-

ples. However, appreciation of nature is also a cen-

tral component of preparing and enjoying tea in

Japan. Shinto and Buddhism have long coexisted in

Japan, and both religions also incorporate profound

regard and respect for the natural world. The Shinto

tradition proposes that sacred beings (kami) are

manifest in nature. According to Shinto, kami may

reside in rivers, rocks, mountains, or even trees. Tea

utensils, architecture, and related art forms favor

undecorated surfaces and rough or weathered tex-

tures that highlight nature’s beauty, just as these ele-

ments are prized in Shinto rituals and sanctified

Shinto sites. As in Shinto practice, purification also

has a vital role in tea gatherings. Buddhists have

established perspectives on the import of the natural

world, which is a reminder of the transience of

human existence. Buddhism celebrates this belief

through heightened awareness and acceptance of

seasonal changes and other temporal rhythms.

Monks are trained to meditate through concentra-

H ANDBOOK TO L IFE IN M EDIEVAL AND E ARLY M ODERN J APAN

306

tion on the present moment, without regret for the

past or desire for the future, and thereby attain

release. Similarly, chanoyu urges participants to cher-

ish the fleeting beauty of nature’s cycles while shar-

ing a bowl of tea and quiet conversation in natural

surroundings. In addition, most tea wares reflect

Buddhist preferences for economy of design and

subtle decoration.

Tea Ceramics

Ceramics for use in tea gatherings have been care-

fully selected to echo the rustic setting and under-

stated pleasures central to the way of tea. Initially,

ceramics used for preparing and enjoying tea were

Chinese and Korean objects imported by monks and

art enthusiasts, especially during the late Kamakura

and Muromachi eras. Soon, Japanese potters began

to craft wares emulating these imported ceramics,

and some ceramicists emigrated from China and

Korea, thus transmitting ceramic production tech-

niques and types directly to artisans working in the

Japanese archipelago.

While various tea traditions espouse particular

aesthetic sensibilities regarding ceramic types for tea

preparations, many schools agree on the most desir-

able varieties of ceramic wares for the tea bowl.

Raku ware, Karatsu ware, and Hagi ware are all

ceramic types favored for tea bowls. However, other

varieties, such as Shino, Seto, and Oribe wares, are

also frequently used. Regardless of its origin, the tea

bowl has a special role in tea preparation as the tea

implement that is handled the most, and the object

that best embodies the desired connection between

the host and guest.

ARCHITECTURE

There are at least two ways in which the study of

medieval and early modern architecture might be

organized: temporally—in sequential order from

style to style—and functionally—buildings typed as

religious or secular. Both these approaches seem

commonsensical, but both also introduce particular

difficulties with regard to architecture in medieval

and early modern Japan.

In the temporal approach, for instance talking

about “medieval” or “early modern” architecture,

there is a need to account for the fact that temples

and shrines might be constructed in one period but

have additions or other stylistic changes made to

them over the centuries. Initially, a structure might

be constructed in one style but come to reflect the

accretion of multiple styles belonging to different

time periods. Similarly, shrine and temple buildings,

despite the vagaries of weather, fire, and other nat-

ural predators of wood construction, sometimes

endured over the centuries and were important in

multiple time periods, their architectural styles a

part of periods far removed from their original time

of construction. In at least one famous instance—the

Ise Shrine—the architectural style is very old but the

shrine buildings are rebuilt every 20 years as a means

of ritual purification. Hence, the buildings are

always new but exhibit an old architectural style.

The distinction between religious and secular

architecture is also fraught with problems and ambi-

guities. Some architectural forms, such as the Shoin

style (see below), were derived from both Buddhist

and aristocratic sources. Secular retirement villas

might be turned into Buddhist temples, as in the

case of Kinkakuji and Ginkakuji (see below). The

blending of the religious and secular was not unique

to Japanese architecture, but was rather indicative of

a worldview that did not make sharp distinctions

between the sacred and the profane. While temporal

and functional categories are suggested below, they

should not be treated as definitive categories for

organizing medieval and early modern Japanese

architecture.

Buddhist Architecture

Buddhist architecture refers to building styles asso-

ciated with temples and temple complexes. Buddhist

temple complexes consisted of multiple structures

functioning in concert to create a contained com-

munity that met both the spiritual and material

A RT AND A RCHITECTURE

307

needs of those residing there. Fundamentally, tem-

ples were places dedicated to a variety of Buddhist

practices and functions. Different buildings were

constructed for these different functions. Temple

compounds had buildings for worship of the Bud-

dhas and bodhisattvas, dwellings for monks or nuns,

halls for religious training and practice, and also

places to house texts and other important religious

objects. In most cases, temples also served as gather-

ing places for members of the laity.

Prior to the medieval period, there had been

ideas about the proper number and configuration of

buildings for a Buddhist temple complex. However,

by the Kamakura period, temples were typically

designed according to one of three different styles,

or in a style combining the three. Thus, not all tem-

ples were designed in the same way or with the same

layout of buildings and grounds, and different Bud-

dhist schools utilized different configurations.

STYLES OF BUDDHIST

ARCHITECTURE

Styles of Buddhist architecture changed over the

centuries. In general, they were a combination of

both Chinese and indigenous Japanese styles. In the

medieval period, the preexisting Japanese style

(wayo) of Buddhist architecture was used, along with

two new important Buddhist architectural styles

first developed in the early medieval period: the

Great Buddha style (daibutsuyo) and the Zen or Chi-

nese style (karayo). By the end of the Kamakura

period, temple construction started to borrow from

the different Buddhist architectural styles to create

a hybrid or eclectic style (setchuyo) that utilized ele-

ments from the Japanese, Great Buddha, and Zen

styles. While use of the three main architectural

styles continued in the early modern period, a

fourth style—Obaku style—was imported from

China and was primarily associated with the Obaku

Zen school.

One of the distinguishing characteristics of Bud-

dhist architecture generally is the style of bracketing

used to support the roof and eave of a temple on the

outside of a building and the ceiling on the inside.

Bracketing served both structural and aesthetic

functions. Different Buddhist architectural styles

used different bracketing systems and thus bracket-

ing became one of the architectural features that set

different styles apart from each other.

Japanese Style (wayo) In its use as an architectural

term, wayo or Japanese style refers to the style of

Buddhist architecture current in Japan beginning in

the Nara period. Despite the term, Japanese style is

in fact the overlay of Japanese architectural styles—

such as the use of unpainted and untreated wood,

simple ornamentation, and curved lines—over styles

imported from Tang-dynasty (618–906) China.

Once Tang-style architecture was introduced to

Japan, it evolved into a Japanese style throughout

the course of the Heian period. The term wayo was

created in the early medieval period to contrast the

older architectural style with new styles then becom-

ing prevalent, imported from the Asian mainland.

Although Japanese-style Buddhist architecture

was largely supplanted in the Kamakura period by

new styles, it was nevertheless employed in some

important temple rebuilding projects. Of particular

note was the use of Japanese style to rebuild struc-

tures at two Nara temples, the Kofukuji and the

Todaiji, that were destroyed during the Gempei

War.

Great Buddha Style (daibutsuyo) or Indian Style

(tenjikuyo) The Great Buddha style (daibutsuyo) of

Japanese Buddhist architecture is also referred to as

Indian style (tenjikuyo). The term tenjikuyo was used

in the medieval period; daibutsuyo is a modern term

coined to more accurately describe this aspect of

Japan’s architectural history. Although tenjikuyo

means “Indian style,” this architectural style actually

makes no visual reference to Indian design modes.

Rather, it refers to south China architectural style

blended with traditional Japanese design features.

The term daibutsuyo was named after the style of

the Todaiji Great Buddha Hall (daibutsuden) when it

was rebuilt through the efforts of the priest, Chogen

(1121–1206), who had introduced Indian style to

Japan after returning from his travels in southern

China during the Song dynasty. The Great South

Gate (nandaimon) at Todaiji, designed by Chogen

and built at the same time as the Great Buddha Hall,

is an important example of the Great Buddha style

still extant. Chogen’s Great Buddha Hall construc-

tion burned in 1567 and was later rebuilt in a similar

H ANDBOOK TO L IFE IN M EDIEVAL AND E ARLY M ODERN J APAN

308

style. Use of the Great Buddha style was largely

abandoned soon after Chogen’s death, though some

of its details and elements were incorporated into

other architectural styles.

Zen Style (zenshuyo) or Chinese Style (karayo)

The Zen style (zenshuyo) of Buddhist architecture

was imported from China during the Kamakura

period. An important extant example of this style is

the Relic Hall (shariden) at the Engakuji constructed

in the medieval period in the city of Kamakura. The

Zen style, as an architectural term, is a modern

coinage. The term used during the medieval period

was Chinese style or karayo, reflecting the importa-

tion of this style from Song-dynasty (960–1279)

China. As the name implies, the Zen style was par-

ticularly associated with design elements used for

building Zen temple complexes in the medieval

period.

The Zen style introduced new design elements

into the construction of temples. Among these inno-

vations were novel styles of ornamentation, up-

wardly curved fan rafters, and bell-shaped windows.

Although Zen style was based on Chinese models,

Japanese designers innovated on the borrowed

design to create an architectural style different from

its Chinese counterpart. The roof structure, for

instance, was modified to meet Japanese practical

and aesthetic needs.

Obaku Style The Obaku style of Buddhist archi-

tecture was introduced to Japan in the late 17th cen-

tury and is associated with Zen temples belonging to

the Obaku school. The Obaku school of Zen Bud-

dhism was imported from China to Japan in the

middle of the 17th century. The Mampukuji in Uji

(south of Kyoto), constructed in the 1660s, exempli-

fies the Obaku style. The Obaku architectural style

uses traditional Zen features, but also incorporates

design elements from Chinese Buddhist architec-

tural forms of the late Ming (1368–1644) and early

Qing (1644–1912) dynasties, including the physical

layout of the temple grounds. Among the Chinese

architectural innovations apparent at Mampukuji

and other Obaku temples are such features as open

corridors running between temple buildings, a four-

tiered bracketing system, intricately carved pillar

base stones, and decorative railings.

BUDDHIST COMPLEXES

AND BUILDINGS

Typical kinds of buildings and structures found at a

temple complex—besides those for everyday func-

tions such as kitchen, dining hall, dormitory, bath-

house, and latrine—included those in the following

list. Note that not all temple complexes necessarily

had all of these kinds of buildings and structures,

and some may have had variants of these buildings,

depending on the particular Buddhist school.

main hall (kondo or hondo or butsudo or butsuden

or Amidado) The location of a temple’s most

important images of Buddhas and bodhisattvas. The

term kondo (golden hall) was used particularly in

the Nara and Heian periods. Although the term was

also used during the medieval and early modern

periods, the term hondo (main hall) became much

more widely used to refer to a temple’s main hall.

The term butsudo (Buddha hall) is a generic term for

a main hall housing a Buddha image. The term but-

suden (Buddha hall) refers to the main hall at a Zen

temple. The term Amidado refers to the main hall at

a Pure Land temple.

lecture hall (kodo or hatto) The term kodo refers to

a lecture hall used by Buddhist schools other than

Zen. Buddhist statues are usually placed inside the

kodo, and the lecturing priest stands in front of them.

The term hatto (literally, “Dharma Hall”) refers to

the lecture hall at a Zen temple. Typically, Buddhist

imagery is not used in a Zen lecture hall.

meditation hall (zendo) A Zen temple meditation

hall used especially for the practice of zazen, or

seated meditation.

pagoda (to) The Buddhist structure known as a

pagoda (to; literally, “tower”) was, in Japan, usually a

wooden, multitiered structure that housed relics of

the historical Buddha’s bodily remains. The pagoda

form and function originated in Indian Buddhist

architecture where the stupa, as it was called in San-

skrit, was a hemispherical dome made of earth and

stone. The stupa became formalized into the East

Asian pagoda, a much taller and narrower structure

made of wood. Both stupas and pagodas are crowned

A RT AND A RCHITECTURE

309

with a spire. According to early documents, the

pagoda as a central feature of important Buddhist

complexes was introduced to Japan by the end of the

sixth century.

sutra repository (kyozo) A text repository housing

Buddhist scriptures and commentaries as well as

temple documents

bell tower (shoro) Housing for the temple bell that

was rung to mark specific ritual occasions or other

events

gates (mon) Buddhist temple gates functioned to

set apart the temple grounds from the outside world.

Gates within a temple complex created spaces within

the larger temple grounds that were set apart as espe-

cially sacred or ritually important. Temples were

sometimes divided according to an inner and outer

precinct demarcated by a gate. Some gates could be

quite large and imposing, signifying the importance

and power of a particular temple complex.

ARCHITECTURE UNDER THE

ASHIKAGA SHOGUNS

Two Muromachi-period pavilions that attest to the

pervasive influence of Zen Buddhism also reflect

the seamlessness of secular and religious culture

under the patronage of the Ashikaga shogunate

(1333–1573). Originally constructed as villas for

retirement, these two structures are known today

as Kinkakuji (Temple of the Golden Pavilion; ori-

ginally Rokuonji) and Ginkakuji (Temple of the Sil-

ver Pavilion; originally Jishoji), although the

buildings were not converted into temples and given

their present names until after the deaths of their

owners.

The third shogun, Ashikaga Yoshimitsu, de-

monstrated his passion for Chinese visual and

literary arts when he ordered his three-story, dou-

ble-roofed pavilion constructed in the Kitayama

(Northern Hills) district of Kyoto. The pavilion is

modeled on a type of scholarly retreat seen in Chi-

nese painting. Situated within an extensive array of

gardens for strolling modeled on Chinese prece-

dents, Kinkakuji is resplendent with gold foil cover-

ing the exterior. Inside, the structure includes space

on the first floor dedicated to informal leisure activ-

ities such as contemplating the gardens and lake, and

an L-shaped veranda on the second level for Moon-

viewing. During Yoshimitsu’s lifetime, the pavilion

served as an appropriate spot for the poetry gather-

ings he liked to host, and upon his death, its conver-

sion to a temple memorialized his enthusiasm for

cultural pursuits connected with Chinese aesthetics.

Thus, Kinkakuji was among the most visible mani-

festations of Chinese influence in Japanese art and

architecture of the 14th century.

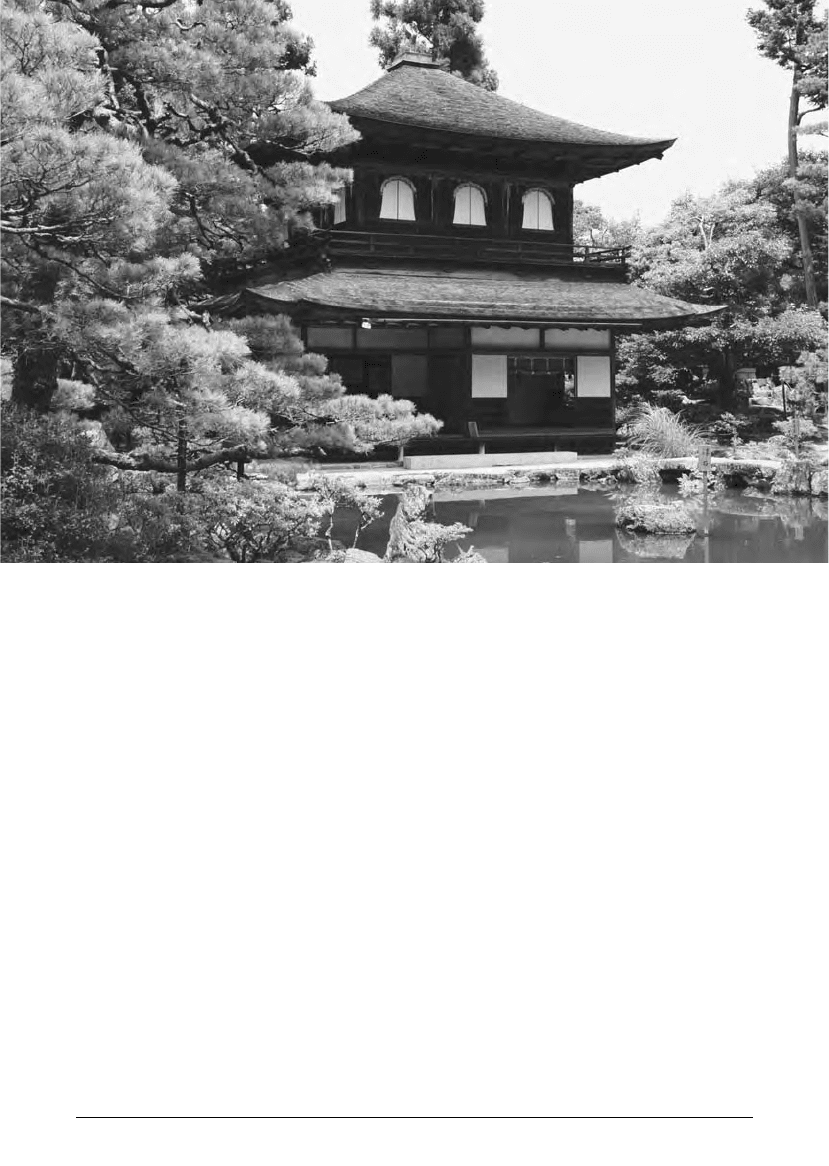

In the later half of the 15th century, Yoshimasa

(1436–90), eighth Ashikaga shogun (ruled 1449–74)

and Yoshimitsu’s grandson, continued the tradition

of Ashikaga patronage established by his grandfather

as he erected a pavilion dedicated to cultural pursuits

in the eastern hills of Kyoto (Higashiyama district).

Today, Yoshimasa’s villa is popularly known as

Ginkakuji (Temple of the Silver Pavilion) due to the

spurious legend that the entire exterior was to have

been covered with silver leaf, just as the exterior of

Kinkakuji is covered with gold foil. Yoshimasa may

have intended to cover the interior second floor of

the two-story pavilion, a Kannon hall, with silver

leaf, although this project was not accomplished.

The first floor of the double-roofed structure was

used for meditation and had sliding doors (fusuma)

that could open to reveal the gardens and lake also

designed for the complex.

Another building on the site, a single-story struc-

ture known as the Togudo, housed a room created

for preparing and enjoying tea in the style favored

by the tea connoisseur and Zen monk Murato Shuko

(1422–1502). Under the influence of Shuko (also

known as Juko), who encouraged adhering to Bud-

dhist precepts while making and sharing tea, tea

consumption and related arts became a formalized

ritual known today as chanoyu. Today, Yoshimasa’s

pavilion is officially known as Jishoji, a temple affili-

ated with the Rinzai school of Zen Buddhism.

Although not formally dedicated as a temple until

the death of Yoshimasa, this structure had a promi-

nent place in the Zen-infused environment of 15th-

century Kyoto.

Yoshimasa’s ineffectual rule aggravated political

and civil unrest in the capital that eventually culmi-

nated in the Onin War of 1467–77 and subsequent

internecine conflicts. However, his artistic preoccu-

H ANDBOOK TO L IFE IN M EDIEVAL AND E ARLY M ODERN J APAN

310

pations yielded significant developments in various

cultural spheres during his tenure as shogun. Gin-

kakuji, where he settled in 1483, became a haven for

cultivating leisure pursuits. At first, Yoshimasa

relied upon tonseisha (nominal Buddhist clerics) for

discernment in cultural matters as his grandfather

had. However, many of these figures left the unsta-

ble climate of the capital for provincial temples and

domains, and Yoshimasa turned to a family of nom-

inal clerics known as the San’ami, who advised him

on connoisseurship and display and served as cura-

tors of the Ashikaga collection. These men had a

family affiliation with the Pure Land school of Bud-

dhism, a clerical connection in name alone that was

reflected in their use of the suffix ami (from Amida).

Under the influence of these figures, Noami

(1397–1471), Geiami (1431–85), and Soami

(1455–1525), both townspeople and regional lords

participated in tea gatherings, garden design, con-

noisseurship of ceramics and lacquerwares, and

flower arranging at Ginkakuji. The cultural milieu

of this pavilion and its adherents was thus flavored

with the aristocratic heritage of Kyoto, the old cap-

ital, as well as the sensibilities of the newly powerful

warrior classes.

Shinto Architecture

Shrine (jinja) architecture refers to building styles

associated with Shinto shrines. Shrines are located

within a space demarcated as sacred because a kami

(deity) is enshrined there. Shinto shrine precincts

include not only a building or buildings for wor-

shipping the kami but also buildings for ritual per-

formances. Shinto architecture incorporates both

indigenous design elements and borrowings from

Chinese and Buddhist architecture. Thus, for in-

stance, some shrines utilize the indigenous aesthetic

of plain wood while others are painted a bright ver-

milion color.

STYLES OF SHINTO ARCHITECTURE

There were many thousands of Shinto shrines in

Japan during the medieval and early modern periods

(as there are today) of varying importance and size.

The majority were small and shared a similar archi-

tectural style, typically nagare-zukuri or kasuga-

zukuri (see below). Larger shrines, however, often

had their own distinctive design style. A particular

style of Shinto architecture was usually named after

the style of the main sanctuary (honden) of the shrine

A RT AND A RCHITECTURE

311

10.1 Bell tower and temple bell at the Engakuji in

Kamakura. This bell, designated a National Treasure by

the Japanese government, was cast by members of the

Mononobe family, the best-known bronze artisans of the

Kamakura period. Donated in 1301 by Hojo Sadatoki to

the Engakuji in Kamakura, unlike Western bells, this

bell has no clapper and is traditionally struck by a log to

create a deep resonance.

(Photo William E. Deal)

precincts. Among the most important Shinto archi-

tectural styles are:

Shimmei Style (shimmei-zukuri) The Shimmei

(“sacred brightness”) style is associated with the ear-

liest Shinto shrines. These ancient shrines evolved

from the design of granary storehouses. This style is

exemplified by the Inner Shrine (naiku) at the Ise

Shrine. It is here that Amaterasu, the sun goddess, is

enshrined. According to Japanese mythology, the

imperial family is descended from her lineage. The

Ise Shrine, an important Edo-period pilgrimage des-

tination, is rebuilt every 20 years as an act of purifi-

cation.

Nagare Style (nagare-zukuri) Nagare (“flowing”)

style is the most common form of main sanctuary

(honden) Shinto architecture. It is a style that is found

throughout Japan, especially in smaller regional

shrines. Nagare-style shrines have an asymmetrical

gable roof with a long, extended sloping front. The

two Kamo Shrines in Kyoto typify this style.

Kasuga Style (kasuga-zukuri) The Kasuga style

refers to the architectural style found at the Kasuga

Shrine in Nara and widely used at smaller shrines in

the Nara and Kyoto areas. The Kasuga style is sec-

ond only to the Nagare style in its prevalence in

shrine construction.

Hachiman Style (hachiman-zukuri) The Hachi-

man style is used in the main sanctuary (honden) and

worship hall (haiden) at shrines dedicated to the kami

Hachiman. This style is distinguished by its use of

two Nagare-style shrines, one in front and one in

back, with the two buildings touching at the roof

H ANDBOOK TO L IFE IN M EDIEVAL AND E ARLY M ODERN J APAN

312

10.2 Ginkakuji, in Kyoto (Photo William E. Deal)

eaves. This linked building style was borrowed from

Buddhist architecture. The building in front is the

worship hall and the back building houses the main

sanctuary. The Iwashimizu Hachiman Shrine in

Kyoto and the Tsurugaoka Hachiman Shrine in

Kamakura are extant examples of shrines using the

Hachiman style for their main sanctuaries and wor-

ship halls.

Hiyoshi Style (hiyoshi-zukuri) The Hiyoshi style,

also commonly referred to as the Hie style (hie-

zukuri), is particularly associated with the extant

Hiyoshi (or Hie) Shrine. This shrine is located at the

foot of Mt. Hiei and is the guardian shrine of

the Enryakuji, the Tendai-school headquarters atop

the mountain. The Hiyoshi style is a variation of the

Nagare style.

Taisha Style (taisha-zukuri) The Taisha (“grand

shrine”) style is associated with the extant Izumo

Shrine (taisha) in present-day Shimane Prefecture.

Like the Shimmei style, the main sanctuary has a

raised floor suggestive of ancient granaries that

required an elevated floor for air circulation. Other

shrines in this region of Japan also use a similar con-

struction technique. Other distinctive features of

this architectural style include a roofed staircase

leading into the main sanctuary.

Sumiyoshi Style (sumiyoshi-zukuri) The Sumi-

yoshi style is associated with the style of the main

sanctuary (honden) at such Shinto sites as the

Sumiyoshi Shrine in the Osaka area. This style is

characterized, in part, by the division of its interior

space into two parts, and by the use of a gable roof

covered with cypress bark and extended eaves.

Gongen Style (gongen-zukuri) Gongen style

refers to Tosho Daigongen (Eastern Light Great

Incarnation), the posthumous name of Tokugawa

Ieyasu (1542–1616). The term gongen (or daigongen,

great gongen) means “incarnation.” The posthumous

name for Ieyasu, “the great incarnation Tosho,”

implies his manifestation as a deity at his death. As a

kami, Ieyasu is enshrined in the Toshogu at the

famous Nikko Shrine, an important early modern

edifice. The Toshogu architectural style, conspicu-

ous for its ornate decorative elements, is known as

the Gongen style. This style has a complicated roof

design that joins together the main sanctuary and

the worship hall.

SHRINE COMPLEXES

AND BUILDINGS

The number, kinds, and arrangement of buildings at

a shrine complex varied depending on the size and

importance of the shrine. Minimally, a typical shrine

included a main sanctuary and a worship hall. A

large shrine might also include a meeting hall for

shrine members, a storehouse, a hall for ritual meals,

a shrine office, a hall for ritual purification, and

priest quarters. Although shrine buildings might be

placed in a number of different physical configura-

tions, the precincts, regardless of size, typically had a

gate to mark the entrance to the shrine grounds.

Water basins (called temizuya or chozuya) were acces-

sibly placed so that worshippers could purify them-

selves by rinsing their hands and mouth with the

water before entering the central area of the shrine

grounds. Pathways lead to the main sanctuary and

worship hall.

In the medieval and early modern periods, it was

not unusual to find Shinto shrines and Buddhist

temples occupying adjoining spaces. This was the

result of the medieval tendency to view gods, Bud-

dhas, and bodhisattvas as different aspects of the

same sacred power (see chapter 6: Religion). Thus, a

shrine-temple (jinguji) might be located at a Shinto

shrine complex. Or a temple-shrine (jisha) might be

located at a Buddhist temple.

Typical kinds of buildings and structures found at

a shrine complex included those in the following list.

Note that not all shrine complexes necessarily had

all of these different kinds of buildings and struc-

tures, and some had variants of these buildings

depending on size, location, and relative importance

of the shrine.

gate (torii) The gate structure at the entrance to a

Shinto shrine is known as a torii (literally, “bird

perch”). In the medieval and early modern periods,

they were usually made of wood or stone. The torii

marks the gateway into the sacred precincts of the

Shinto shrine. Some are quite large and others

small, and a shrine may have one or many within the

A RT AND A RCHITECTURE

313