Deal W.E. Handbook To Life In Medieval And Early Modern Japan

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

especially in this way. The fan might be closed

to represent a knife or opened to represent the

moon.

The other essential aspect of a Noh performance

was the musicians. They sat on the stage, providing

accompaniment to the verse sections of the play. A

usual grouping of Noh instruments included flute

and drums. There was also a chorus—usually eight

people—that sat in view of the audience. They sang

in unison between the songs performed by the main

and secondary characters.

Among Zeami’s many accomplishments were his

theoretical treatises. He theorized, for example,

about the correct elements required for a Noh play.

In brief, he laid down rules about a play’s subject

matter, its literary style, and its formal structure.

Subject matter varied, but often it derived from sto-

ries already known to the audience concerning fig-

ures, both historical and literary, for whom

unresolved conflict made for an unsettled life and, at

death, prevented a transition to the next life. This

subject matter required a literary style that was,

among other things, aesthetically appropriate,

poetic, affective, and elegant.

Subject matter and style were molded by a pre-

scribed structure that traced a pattern of 1) intro-

duction (jo), 2) development (ha), and 3) climax

(kyu). Not all Noh plays had the same structure, but

this was a common arrangement. Translating this

structure into the actual plot and performance of a

play typically yielded the following sequence of

events:

Introduction: entrance of secondary character

(waki); the secondary character is typically a trav-

eler who explains the place and time of the play’s

dramatic locale.

Development: (in three sections)

Section 1: entrance of the main character (shite)

and, in some plays, the main character’s compan-

ions or attendants (tsure)

Section 2: dialogue between the secondary and

main characters. The secondary character is a

stranger, a traveler, who does not know about

the history and other details concerning the

location he has come to. He therefore asks the

main character about the locale and to explain

what important events have transpired there.

Section 3: explanation. The main character explains

what important events have transpired in the

locale that the stranger has come to. This narra-

tive of historical details usually occurs as a dance

(kusemai). The detail provided by the main char-

acter leaves the secondary character wondering

how anyone can have such intimate knowledge

of events that transpired so long ago.

Climax: Reappearance of the main character in

changed form, revealing her or his true identity.

The revelation usually includes a dance perfor-

mance. Once all is revealed, the protagonist

receives some form of assistance from the sec-

ondary character and is now freed from the

karmic ties binding her or him to this world.

By the end of the Edo period there were around

250 plays in the standard Noh repertoire. These

plays were organized into five groups according to

subject matter. One play from each group consti-

tuted a traditional Noh performance program.

Thus, a medieval or early modern theatergoer

would have seen a play from each category in an

afternoon of Noh theater. The five groups are:

God Plays: a religious play in which a deity figures

prominently

Warrior Plays: plays about warriors or male protag-

onists; the plots are often taken from tales told

about the warriors who fought in the Gempei

War (1180–85) found in the Heike monogatari

(Tale of the Heike).

Women Plays: plays about elegant, courtly women;

these plays are often referred to as “wig” plays.

Miscellaneous Plays: these plays often have a living

person or “madwoman” as the protagonist; these

plays deal with human character traits and emo-

tions, such as bravery, jealousy, and love.

Demon Plays: plays that deal with beings such as

demons and ghosts.

Noh play texts are composed of both poetry

(utai) and prose (kotoba). Prose sections of plays are

chanted rather than spoken in a conversational tone,

and there are prescribed rules for the speed and

cadence of the chanting. Poetry sections are sung to

the accompaniment of music. They include verse

from classical Japanese poetry collections and some-

times passages from Buddhist texts.

H ANDBOOK TO L IFE IN M EDIEVAL AND E ARLY M ODERN J APAN

274

Buddhist aspects of Noh plays are significant. In

fact, Noh plays cannot be understood without an

understanding of the Buddhist assumptions that

drive the plot and the resolution of a play’s tensions.

These ideas would have been immediately recogniz-

able to medieval and early modern audiences. For

instance, a play’s protagonist (the shite role) often

appears in one guise at the beginning of a play only

to transform into another form by play’s end.

Because the protagonist is often the unsettled spirit

of a warrior or some other famous figure seeking

resolution to some longstanding conflict, the themes

of Japanese Buddhist thought, stressing notions of

karmic consequence and the fundamental instability

and impermanence of the world, are critical. Reality

is not fixed and stable, but fluid and changing. Thus,

the otherworldly sensibility conveyed in many Noh

plays and the movement of spirits in and out of the

perceptions of the living would have seemed natural

to most medieval and early modern theatergoers.

The notion of the priest as intermediary between

the world of the living and the world of the dead was

symbolically enacted by the actors of the Noh play.

SOME REPRESENTATIVE NOH PLAYS

LISTED ACCORDING TO THE

FIVE TYPES

God Plays

• Chikubujima

• Kamo

• Oimatsu

• Takasago

• Yo ro

• Yumi yawata

Warrior Plays

• Atsumori

• Kiyotsune

• Sanemori

• Tadanori

• Tomoe

• Yashima

• Yorimasa

Women Plays

• Hagoromo

• Izutsu

• Matsukaze

• Nonomiya

• Obasute

• Saigyo zakura

• Yuya

Miscellaneous Plays

• Aoi no ue

• Ataka

• Aya no tsuzumi

• Dojoji

• Kantan

• Kinuta

• Sumidagawa

• Uto

Demon Plays

• Funa benkei

• Momijigari

• Nue

• Shakkyo

• Tsuchigumo

• Yamamba

Kyogen

Kyogen (“mad words”) was a comic theatrical form

with close associations to Noh. Kyogen performances

were either independent plays or comic interludes

interspersed within the scenes of a serious play. Kyo-

gen is also sometimes referred to as ai-kyogen (“kyogen

in the spaces”) in reference to its performance

between Noh scenes. Like Noh, Kyogen traces its

development back to medieval sarugaku traditions. It

represents the extension of comic aspects of sarugaku

into early modern Kyogen. In modern scholarship,

Kyogen’s connection with Noh has often overshad-

owed the study of Kyogen as a separate and distinct

tradition. But Kyogen had distinct schools of perfor-

mance and its own repertoire of plays even though it

shared the same stage with Noh performers.

Kyogen was integrated into Noh performances in

different ways. Sometimes Kyogen actors performed

between acts in a Noh play, offering comic relief

from the seriousness. The Kyogen actor, in the sim-

ple garb of a commoner, would explain to the audi-

P ERFORMING A RTS

275

ence in colloquial language aspects of the Noh play

being performed, including plot and background

information. This provided the audience with poten-

tially greater clarity than the difficult literary lan-

guage used in the play might otherwise provide.

Kyogen actors sometimes performed within the play

itself, dancing or playing a role, such as a beggar, that

had the purpose of conveying some additional mean-

ing or significance to the plot. Besides their functions

within Noh, Kyogen comedies were sometimes per-

formed as independent plays.

Originally, Kyogen was an improvised perfor-

mance in which the actors worked only from a

synopsis of the plot. It was not until the 17th century

that Kyogen plays were written down, thereby

largely fixing the play’s performance according to the

written text. The Kyogen repertoire included more

than 200 plays.

Kyogen humor makes light of most social classes

and a variety of human foibles, including clever

retainers and dimwitted lords, husbands and wives,

social snobbery, sons-in-law, and Buddhist clergy. Its

comedic effects are accomplished through a number

of different theatrical strategies including physical

humor, stylized vocalization, verbal puns, mime, and

mimicry. There is also the use of some dance, but

masks are used sparingly, and there is usually no

musical accompaniment.

There are numerous contrasts that can be drawn

between Noh and Kyogen to underscore the funda-

mentally different natures of these two performing

arts. For instance, unlike the characters found in

Noh theater, Kyogen characters are commoners.

Interestingly, the social status of Noh and Kyogen

actors reflected this same distinction between upper

class and commoner, and Kyogen actors were

treated as inferior to Noh actors. Noh plays are

imbued with Buddhist sensibilities that make many

plays seem quite ethereal, focusing the real concern

on the next world or an afterlife. By contrast, Kyo-

gen is firmly grounded in the concrete, here and

now, material world.

Kabuki

Together with Bunraku, Kabuki developed in the

early modern period and was a theatrical form espe-

cially associated with the urban merchant class in

such cities as Edo, Osaka, and Kyoto. Kabuki

became a popular theater form that, like Bunraku,

included music and dance to tell stories about the

exploits of historical figures and about the lives of

merchants and other townspeople.

Kabuki has its origins in women’s traveling per-

formance troupes dating from the late 16th and

early 17th centuries. The leader of one such troupe,

a woman named Okuni, is commonly given credit

for creating Kabuki. Her troupe performed music

and dance, and acted both comedic and dramatic

stories. So-called women’s Kabuki became quite

popular, at least in part because the women perform-

ers were also prostitutes. In 1629, the Tokugawa

shogunate banned Kabuki performances that fea-

tured women performers. In their place, young men

and adolescent boys became the star Kabuki per-

formers. But these young male performers also

worked as prostitutes and, in 1652, the government

banned young men and adolescent boys from acting

in Kabuki performances.

In order to control the moral lapses associated

with Kabuki, the shogunate decided to allow only

performances by adult males who could legitimately

claim to be serious actors. This stipulation was to

have a profound effect on the future development of

Kabuki. By the latter half of the 17th century,

Kabuki had become a performing art in which men

played all the roles, including women’s roles (onna-

gata). It was around this same time that Kabuki the-

aters were constructed in such large cities as Edo,

Osaka, and Kyoto.

As Kabuki became an important theatrical form

in the Edo period, it incorporated aspects of other

theatrical forms, including Noh, Kyogen, and Bun-

raku. Both Noh and Bunraku plays, for instance,

were adapted into the Kabuki play repertoire. By the

late 17th century, Kabuki revolved around three dif-

ferent kinds of performances: 1) historical plays

(jidaimono) that dealt with historical figures, particu-

larly warriors; 2) contemporary plays (sewamono) that

dealt with the lives and loves of merchants and other

townspeople; and 3) dance dramas (shosagoto) that

included music and pantomime.

Music was an essential element of Kabuki, and its

primary function was to accompany a dance seg-

ment. Like Bunraku, the newly popular shamisen

H ANDBOOK TO L IFE IN M EDIEVAL AND E ARLY M ODERN J APAN

276

became the favored instrument driving the melody

of Kabuki music. Kabuki music consisted of both

onstage and offstage music. Onstage music was

divided into two kinds: lyrical (called utamono) and

narrative (called joruri or katarimono). The most

important lyrical form was nagauta (long song), in

which verses were sung to accompany a dance. This

musical style was particularly important in Edo

Kabuki. The most important narrative forms were

kiyomoto bushi (Kiyomoto style) and tokiwazu bushi

(Tokiwazu style), both named after their creators.

Kiyomoto bushi was happy and bright, while Toki-

wazu bushi was heavily influenced by a Bunraku

musical style known as gidayu bushi (Gidayu style).

These musical forms were performed by onstage

musicians. But there was also music performed off-

stage. Offstage music (geza) served several functions

such as creating special sound effects, suggesting

moods, establishing the locale in which a scene

occurs, identifying characters, and signaling the

beginning and end of a play.

There were different styles of Kabuki dance, but

they generally shared a penchant for the spectacular

and flashy. The most famous Kabuki dances were

those choreographed for onnagata (women’s roles).

Another important aspect of dance was the effecting

of a dramatic pose called a mie. The dancer would

stop, turn his head, sometimes cross his eyes, and

strike a pose that indicated a climatic moment in the

play. The striking of wooden clappers (tsuke) served

to heighten the drama and tension as the actor

moved into the pose.

P ERFORMING A RTS

277

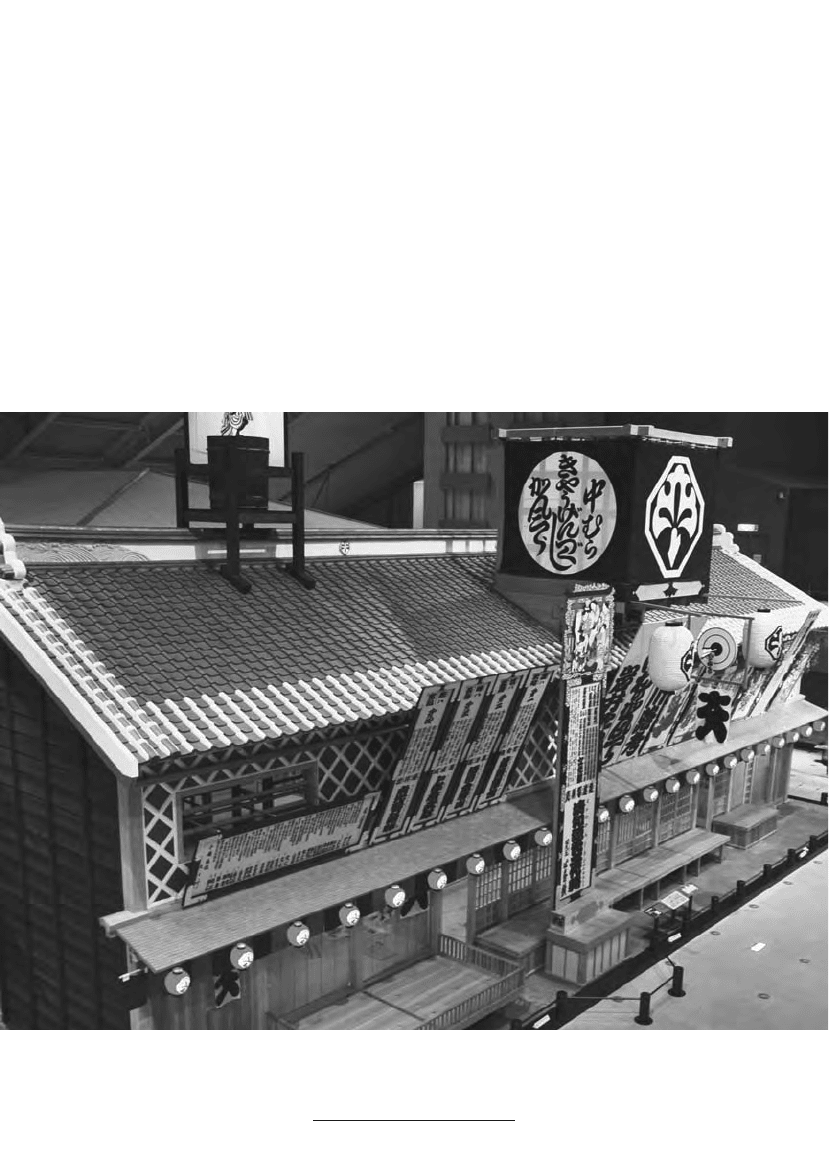

9.4 Replica of the Nakamuraza, a Kabuki theater (Edo-Tokyo Museum exhibit; Photo William E. Deal)

EXAMPLES OF ROLES PERFORMED

IN KABUKI PLAYS

Roles in Kabuki plays were quite varied, but they

were usually assigned to specific categories.

Male Roles (Otokogata)

good male characters (tachiyaku)

• handsome men and amorous men (wagoto)

• straightforward men (jitsugoto)

• heroes and brave men (aragoto)

• warriors (budogata)

Evil Male Characters (Katakiyaku)

• evil men, often warriors (jitsuaku)

• amorous evil men (iroaku)

• old evil men (oyajigata)

• evil men who work for merchants (tedaigataki)

• fools (dokegata)

• comic evil men (handogataki)

Female Roles (Onnagata)

• twenty-something young women (wakaonnagata)

• high-ranking courtesans of the pleasure quarters

(tayu)

• young commoner women (musumegata)

• evil women (akuba or dokufugata)

• old women (kashagata)

Other Roles

• boys or young men (wakashugata)

• old men (oyajigata)

• children (kokata)

SOME IMPORTANT FIGURES IN

EDO-PERIOD KABUKI

Sakata Tojuro I (1647–1709): a Kyoto-Osaka–area

actor who developed a realistic acting style known

as wagoto (“soft business”) that focused especial-

ly on a play’s plot, dialogue, and character devel-

opment.

Chikamatsu Monzaemon (1653–1724): a play-

wright especially associated with Bunraku plays, but

who also wrote plays specifically for the Kabuki

stage. Some of his puppet plays were adapted for

Kabuki performance.

H ANDBOOK TO L IFE IN M EDIEVAL AND E ARLY M ODERN J APAN

278

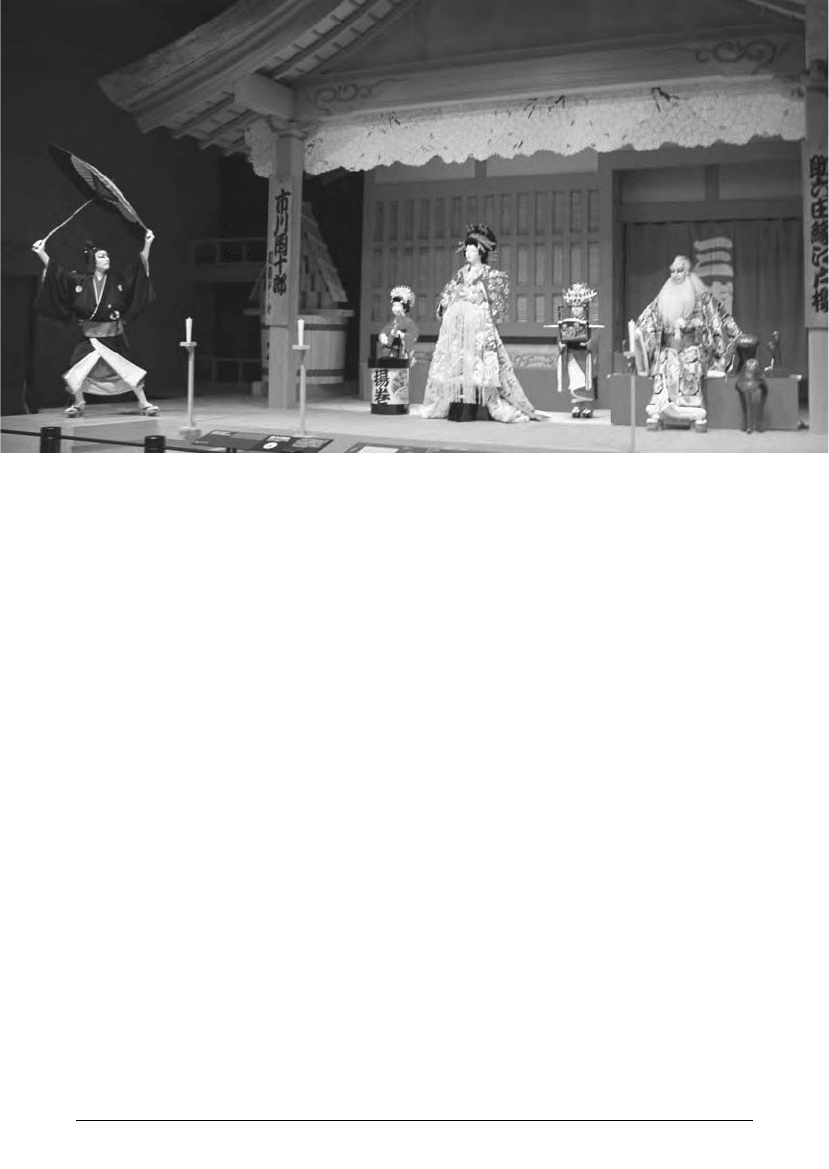

9.5 Recreation of a scene from an Edo-period Kabuki play (Edo-Tokyo Museum exhibit; Photo William E. Deal)

Ichikawa Danjuro I (1660–1704): an Edo-area

actor who developed a flamboyant and particularly

masculine acting style known as aragoto (“rough

business”) that focused on the exploits of brave

heroes who overcame great odds.

Yoshizawa Ayame I (1673–1729): a Kyoto-Osaka–

area actor who established the conventions for the

performance of women’s roles (onnagata).

Namiki Shozo I (1730–73): a playwright and cre-

ator of the revolving stage (mawaributai).

Tsuruya Nanboku IV (1755–1829): a playwright

known for the use of dramatic theatrical effects and

for plays about the lowest classes of Edo society.

Kawatake Mokuami (1816–1893): a playwright

who wrote plays about the lowest classes of Edo

society and whose dramatic sensibilities mark the

transition between late Edo and modern Kabuki.

SOME IMPORTANT EDO-PERIOD

KABUKI PLAYS

The repertoire of Kabuki plays was quite large.

Aside from plays written explicitly for the Kabuki

stage, there were many scripts that were adapted

from plays written originally for Bunraku. To fur-

ther complicate matters, many plays written for

Kabuki and Bunraku have the same title and subject

matter but were written by different playwrights.

Despite these complications, some of the most

famous Kabuki plays include the following:

Japanese Common English

Title Title

Aoto-zoshi hana no nishiki-e Benten the Thief

Ichinotani futaba gunki Chronicle of the Battle of

Ichinotani

Kagamijishi The Lion Dance

Kanadehon Chushingura Treasury of Loyal Retainers

Kanjincho The Subscription List

Kenuki Hair Tweezers

Kokusen’ya kassen Battle of Coxinga

Kuruwa bunsho Love Letter from the

Licensed Quarter

Kyo-ganoko musume Dojoji Young Woman at Dojoji

Temple

Meiboku sendai hagi The Disputed Succession

Narukami Fudo Kitayama Narukami and the Deity

zakura Fudo

Sakura hime azuma The Scarlet Princess of

bunsho Edo

Sanja matsuri Sanja Festival

Shibaraku Wait a Minute

Soga no taimen The Soga Confrontation

Sonezaki shinju Love Suicide at Sonezaki

Sugawara denju tenarai Secret of Sugawara’s

kagami Calligraphy

Sukeroku yukari no Edo Sukeroku: Flower of Edo

zakura

Tokaido Yotsuya kaidan The Ghost of Yotsuya

Tsumoru koi yuki no seki Love Story at the Snow-

no to Covered Barrier

Ya no ne Arrowhead

Yoshitsune sembon zakura 1,000 Cherry Trees

Bunraku

Bunraku, the puppet theater that developed in the

late 16th and 17th centuries, was originally referred

to as ningyo joruri (puppetry with chanted accompa-

niment). The name “Bunraku” dates from the early

1800s. Although the idea of puppet theater might

conjure up notions of plays and storytelling for chil-

dren, Bunraku was serious theater with stories, both

serious and comedic, intended for adults.

Puppet theater originated from the combination

of other performing arts—including chanted narra-

tive (joruri), puppets to illustrate the story, musical

accompaniment on the newly popular shamisen, and

dance—into a new theatrical form. Joruri is a gen-

eral term referring to chanted narratives accompa-

nied by shamisen music. Another important influence

on Bunraku was Kabuki. Especially important in the

development of Bunraku was its borrowing of some

of the technical aspects of Kabuki production.

The origins of puppet theater can be traced to

the 11th century, although its history up to the Edo

period is not well known. In the mid-17th century,

puppet theater, combining the manipulation of pup-

pets with chanted narrative, was already popular in

P ERFORMING A RTS

279

cities such as Osaka and Kyoto. It was not until the

late 17th century, however, that Bunraku became a

fully developed performing art. This occurred be-

cause of the collaboration between a joruri chanter,

Takemoto Gidayu (1651–1714), and a playwright,

Chikamatsu Monzaemon (1653–1724). Together

they gave a new and dramatic form to the theatrical

style that would become Bunraku.

Gidayu made a name for himself as a master of

narrative chant. His joruri chanting style bears his

name: Gidayu-bushi (Gidayu-style recitation). He

employed this style of narrative chanting, with solo

shamisen accompaniment, in a puppet theater he

founded in Osaka in 1684. This style would later

have a significant influence not only on other styles

of joruri chanting, but also on the styles of music

that developed within Kabuki. Gidayu engaged

Chikamatsu, who was already well known for his

Kabuki plays, to write plays for his theater. In the

years of collaboration with Gidayu, Chikamatsu

wrote plays that dealt with historical themes and

plays that took up contemporary issues. Plays com-

posed after Chikamatsu’s time sometimes merged

the historical and contemporary play categories.

Chikamatsu’s fame stems primarily from his Bun-

raku plays rather than those he wrote for the Kabuki

stage. His puppet plays can be categorized into two

major groups based on the narrative story line of the

play. The first group is called jidaimono, or period

plays, that narrated historical stories, most often

about warrior exploits. Tales about famous battles or

battlefield heroics were not new, and his audiences

would have known the stories. Yet Chikamatsu and

Gidayu were able to create a theatrical experience

that included not only Gidayu’s masterful chanting

and Chikamatsu’s engaging scripts, but puppets

made to perform acrobatics and other seemingly

impossible movements much to the delight of the

audiences. One of the most famous examples of a

Chikamatsu jidaimono play is Kokusen’ya kassen (Bat-

tle of Coxinga), a story of Chinese patriotism in the

face of the Manchu invasions of China in the 17th

century.

The second group of plays is termed sewamono, or

contemporary plays. These plays were often based

on real events and considered issues of immediate

interest to his audience. Through his use of current

events, Chikamatsu explored the morality of the

times and the dilemmas confronted by those whose

lives led them to deviate from the Neo-Confucian

values set down by ruling-class warriors. One

famous example—and the first sewamono that Chika-

matsu wrote—is Sonezaki shinju (Love Suicide at

Sonezaki, 1703), which dealt with the illicit love

affair between a merchant and a prostitute. Tragedy,

often resulting in suicide, was the usual denouement

of such plays dealing with the conflict between emo-

tional attachment and social mores. This play

became very popular, reflecting the strong audience

interest in the exploration of such themes.

The popularity of Bunraku continued to grow

even after the deaths of Gidayu and Chikamatsu in

the first quarter of the 18th century. In the 1740s,

for instance, three plays were written that became

among the most famous in the Bunraku repertoire.

Among these three was Kanadehon Chushingura

(1748), based on a true incident, which tells the

story of a group of masterless samurai who avenge

the forced ritual suicide of their lord. Bunraku’s

success as a theatrical form presented a challenge to

Kabuki, with which it competed. In order to

counter some of Bunraku’s popularity, Kabuki pro-

ductions incorporated aspects of Bunraku style.

Kabuki actors, for instance, sometimes used a style

of movement that mimicked the way puppeteers

moved the puppets. Sometimes, too, Kabuki used

Bunraku stage techniques to try to heighten inter-

est in its plays. After the middle of the 18th cen-

tury, however, Kabuki was able to eclipse Bunraku

in popularity.

The style of Bunraku created by Chikamatsu

and Gidayu—that elevated puppet theater into one

of early modern Japan’s important performing art

forms—was the consequence of successfully and

creatively combining three elements: recitation,

music, and puppetry. Recitation is performed by

the joruri chanter (known as a tayu). The chanter’s

role is to serve as the voice for all the puppet char-

acters. Since there can be many different roles in a

particular play, the chanter must be capable of pro-

jecting a wide range of voices that include males

and females of differing ages, social classes, and

other characteristics that require speaking in a par-

ticular way.

The music performed in Bunraku usually con-

sists of a solo shamisen (see above for details on this

H ANDBOOK TO L IFE IN M EDIEVAL AND E ARLY M ODERN J APAN

280

instrument), but shamisen ensembles sometimes pro-

vide rhythmic accompaniment in plays adapted from

Kabuki. Both the musical performance and the

chanted word are tied intimately to the movement of

the puppets. It is the puppet, however, that must fol-

low the lead of the shamisen, which sets the narrative

pace and timing through the way the shamisen is

strummed. These aural cues are necessary because

there is little if any eye contact between the pup-

peteers, the chanter, and the shamisen player.

Bunraku theater would not exist without pup-

pets, but the way that puppets have appeared on

stage and how they have been manipulated by pup-

peteers (ningyo zukai) has changed over time. In its

earliest stages, Bunraku puppets were the only fig-

ures seen on stage. Puppeteers, chanters, and musi-

cians were hidden behind a curtain. By the

beginning of the 18th century, however, the tradi-

tion developed to make them visible to the audi-

ence and thus a part of the on-stage entertainment.

Puppets also evolved. They came to have movable

mouths, eyes, eyebrows, eyelids, and hands. With

these elaborations in the form of puppets, it now

required three puppeteers, dressed in black, to

operate the puppets on stage. Puppets ranged in

size from one-half to two-thirds of life size and

weighed as much as 50 pounds. There were also

smaller puppets used for a play’s minor characters

that were operated by only one puppeteer. As pup-

pets became more intricate, so did other aspects of

a Bunraku production, such as set designs and cos-

tumes.

In order for the three elements of Bunraku—

recitation, music, and puppetry—to be compelling

and entertaining, they needed the structure of a

well-told tale. Chikamatsu provided such plays, as

did subsequent Bunraku playwrights.

SOME IMPORTANT EDO-PERIOD

BUNRAKU PLAYS

Japanese Title Common English

Title

Kanadehon Chushingura Treasury of Loyal Retainers

Kokusen’ya kassen Battle of Coxinga

Shusse Kagekiyo Kagekiyo Victorious

Sonezaki shinju Love Suicide at Sonezaki

Sugawara denju tenarai Secret of Sugawara’s

kagami Calligraphy

Tokaido Yotsuya kaidan The Ghost of Yotsuya

Yoshitsune sembon zakura 1,000 Cherry Trees

STREET

ENTERTAINERS AND

STORYTELLERS

There were other forms of performance that oper-

ated outside of the formal music, dance, and theater

traditions. Street entertainment, for instance,

became a significant phenomenon during the Edo

period and contributed to the rise of cities as impor-

tant cultural centers. Such performance modes took

on a variety of forms, and it has been estimated that

there were as many as 300 different kinds of street

entertainers. One might enjoy plays, trained ani-

mals, magic, song and dance, comedic dialogues,

and puppetry on the streets, and vendors sold food,

drink, and even medicine to spectators. While street

entertainment came to have wide popular appeal,

the performers themselves were usually itinerants

and therefore of a very low social class.

In addition to street entertainers, other forms

of performance emerged in the early modern

period. Yose was a kind of Edo-period theater that is

often likened to vaudeville because of the different

types of performances that one might enjoy there,

which included song and dance, comedy, story-

telling, parody, mime, and acrobatics. The popu-

larity of yose is evident from the 390-odd yose

theaters that existed in Edo at the close of the early

modern period. Of particular importance to the de-

velopment of yose were storytelling traditions, some

dating back to the medieval period, that evolved

into performance traditions during the Edo period.

These include rakugo and koshaku, which were per-

formed at yose.

Rakugo, a comic monologue often with a strong

dose of satire, was performed by professional story-

tellers known as rakugoka. The rakugo performer

P ERFORMING A RTS

281

was essentially presenting a play in which he played

all the parts, including narration, and used changes

in facial expressions and vocal intonation to present

the different characters in the story. The performer

typically sat on a cushion in the center of a bare

stage, using only a fan for a prop. One important

feature of a rakugo performance was the rapport that

developed between rakugoka and the audience, espe-

cially since the stories told were often already well

known. The performer created a sense of connec-

tion to the audience by the unique way in which he

told the story.

Koshaku, called kodan since the Meiji period, was

a popular Edo-period performance tradition in

which storytellers recited tales based on historical

narratives and legends. This storytelling tradition

had its origins in the reading and explanation of

Buddhist and other religious texts. By the Edo

period, koshaku had lost its connections to religion,

and the repertoire of stories expanded to include

tales recounting dramatic events concerning war-

riors, lords, merchants and other urban commoners,

and the unsavory side of those living in the cities.

Tales of heroism were also popular. The storyteller

would sit at a desk and narrate a story, clapping

wooden blocks or beating a fan against the desk in

order to build dramatic interest at important junc-

tures in the story.

READING

Musical Instruments

de Ferranti 2000; Malm 2000; Kishibe 1982

Music and Dance

Ortolani 1995; Malm 2000; Kishibe 1982

Religious Performing Arts

Ortolani 1995; Malm 2000; Kishibe 1982

Theater

Ortolani 1995; Inoura and Kawatake 1981; Miner,

Odagiri, Morrell (eds.) 1985, 307–316: Noh,

316–320: Kyogen, 322–325: Joruri/Bunraku, 326–

332: Kabuki, 333: kagura and dengaku stage layouts,

334–335: Noh theater stage layout, 350–357: list of

Noh plays, 357–360: list of Kyogen plays; Dunn

1969, 137–145: Edo-period actors and entertainers;

Kato 1981, 303–313: Noh and Kyogen; Keene 1966:

Noh and Kyogen; Keene (ed.) 1970: Noh plays;

Komparu 1983: Noh; Takeda and Bethe 2002: Noh

and Kyogen costumes, robes, masks, and musical

instruments; Brandon (ed.) 1982: Kabuki and Bun-

raku; Brandon 1975: Kabuki plays; Hare 1986:

Zeami; Rimer and Yamazaki 1984: Zeami; Gerstle

1984: Chikamatsu; Gerstle 2001: Chikamatsu plays;

Brazell (ed.) 1998: anthology of traditional plays;

Brazell (ed.) 1988: Noh and Kyogen plays; Yasuda

1989: Noh plays; Morley 1993: Kyogen plays; Gers-

tle 1999: Kabuki; Torigoe 1999: Joruri and Bunraku

Street Entertainers and

Storytellers

Nishiyama 1997, 228–241

H ANDBOOK TO L IFE IN M EDIEVAL AND E ARLY M ODERN J APAN

282

ART AND ARCHITECTURE

10

With Lisa J. Robertson