Deal W.E. Handbook To Life In Medieval And Early Modern Japan

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

H ANDBOOK TO L IFE IN M EDIEVAL AND E ARLY M ODERN J APAN

244

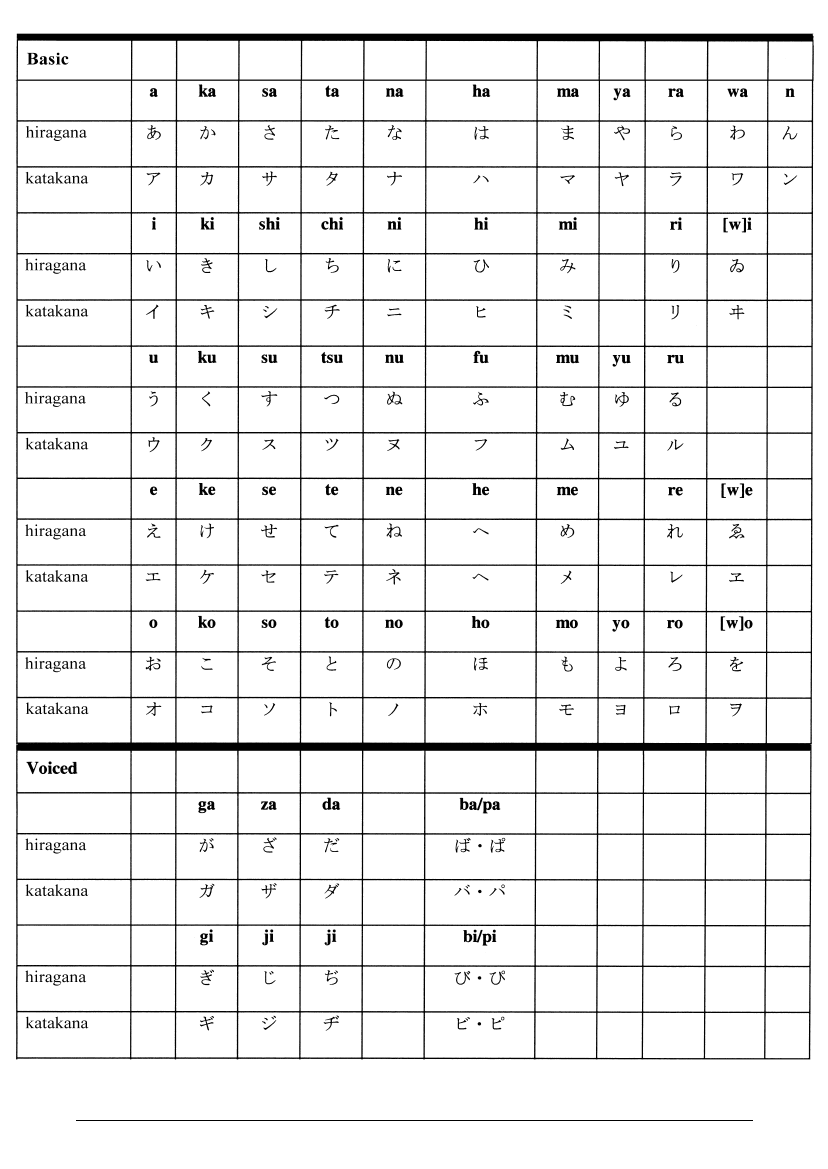

SYLLABIC SOUNDS IN THE JAPANESE LANGUAGE

L ANGUAGE AND L ITERATURE

245

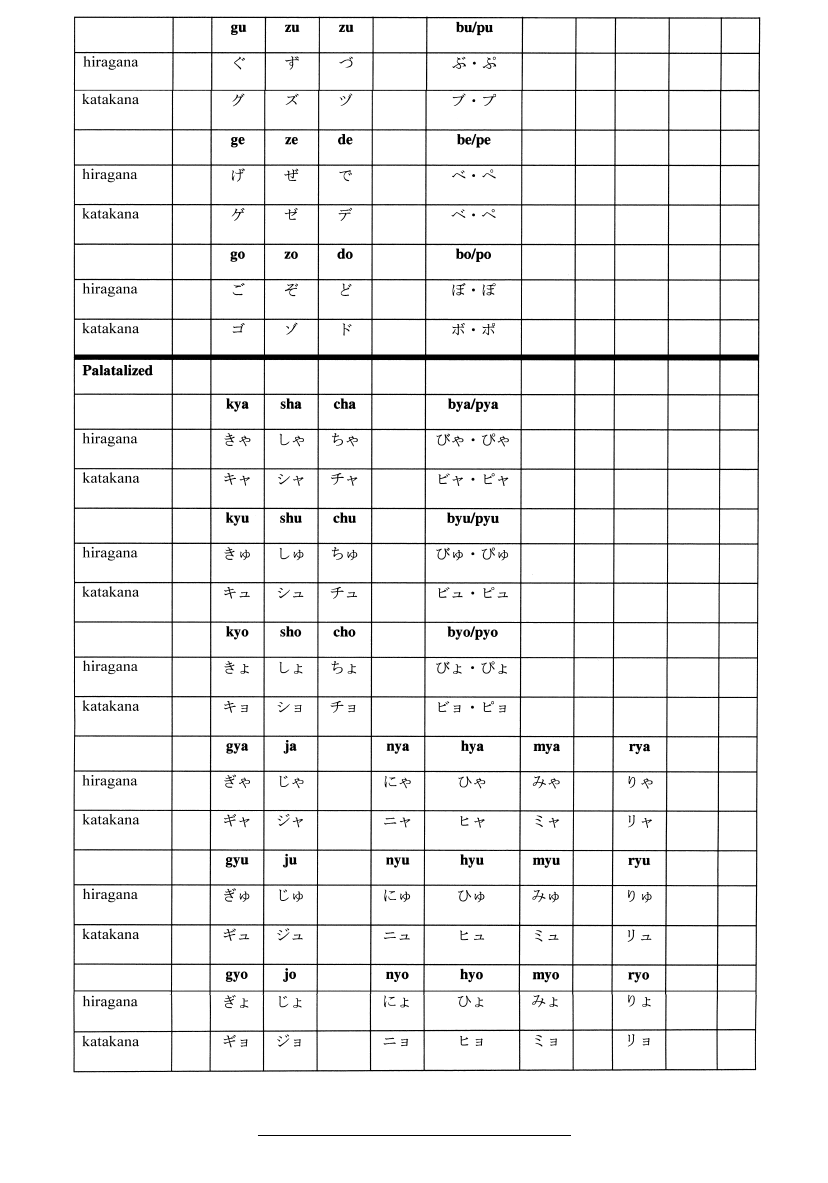

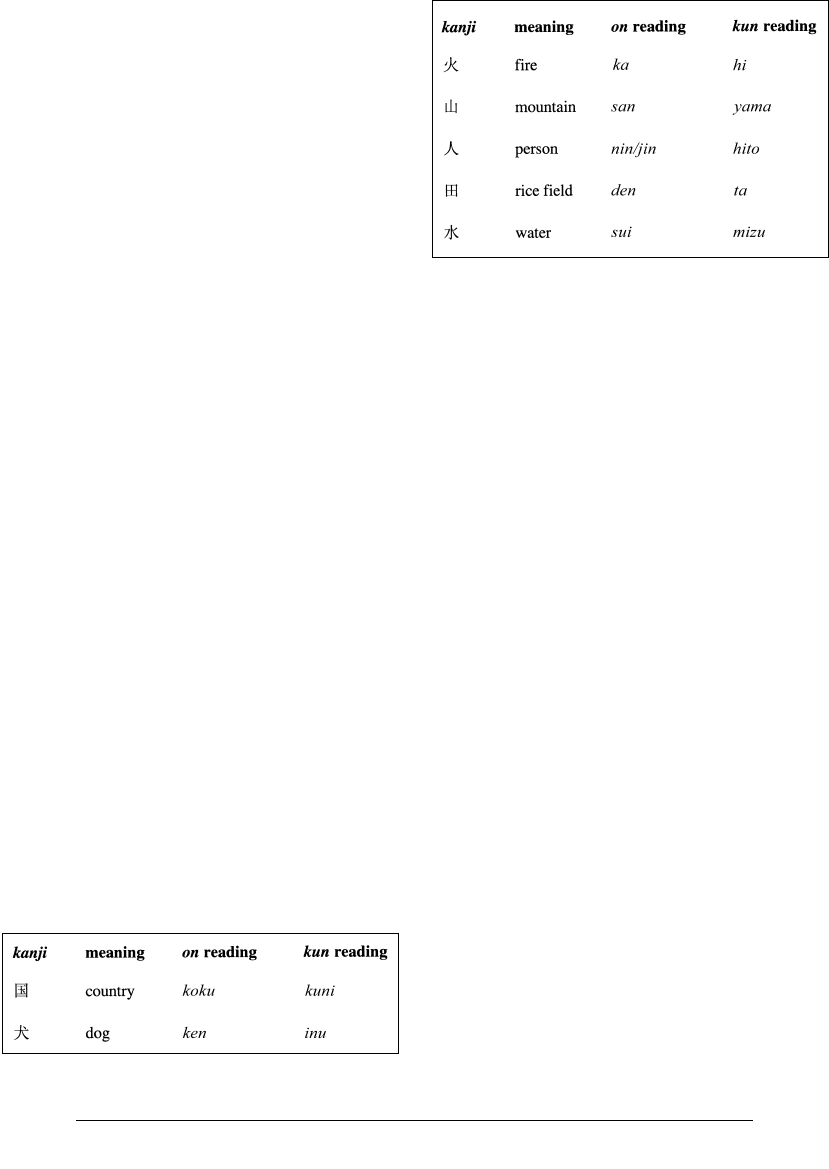

Kanji Pronunciation: on and

kun Readings

Because of the hybrid nature of the Japanese written

language—combining aspects of both written Chi-

nese and spoken Japanese—its historical develop-

ment included two different ways of reading

Chinese characters (kanji). These two different

kinds of readings became known as the on reading

(on-yomi) and the kun reading (kun-yomi). The on

reading, also referred to as the Sino-Japanese read-

ing, is the Japanese approximation of the original

Chinese pronunciation. Chinese pronunciations

required modification to fit with the sounds of the

Japanese language. Some kanji have multiple on

readings. This is the result of the character importa-

tion process: characters came into use in Japan that

in China had different pronunciations depending on

historical period and region of the country. The kun

reading, also referred to as the Japanese reading, is a

native Japanese word that has the same meaning as

the character to which it is applied. Thus, for

instance, the kanji for country has an on reading of

koku. The Chinese pronounce this character guo—

the pronunciation koku is the Japanese modification

of the Chinese sound. The same country character

also has a kun reading of kuni. The word kuni is the

indigenous Japanese term for “country” that has

been applied to the reading of the kanji. Like on

readings, kun readings can be multiple for the same

character. Kun readings are a result of the assign-

ment of Japanese words with similar meanings to the

same character. For characters with multiple on

and/or kun readings, the choice of which pronuncia-

tion to use depends upon the linguistic context in

which the kanji is being used.

EXAMPLES OF ON AND KUN

READINGS FOR SOME COMMON

CHINESE CHARACTERS (KANJI)

Japanese Vocabulary

As a result of both indigenous and foreign influ-

ences on the development of the Japanese language,

there were three different kinds of vocabulary in

use in the medieval and early modern periods:

native Japanese words, Sino-Japanese words, and

foreign words (also referred to as “loan words”).

Sino-Japanese words were Japanese words of Chi-

nese origin, usually written as character com-

pounds, that is, two or more kanji written together

to form words. Sino-Japanese words are often used

to express abstract ideas. Some character com-

pounds are entirely Japanese in origin.

In Japanese, the notion of foreign words typi-

cally refers to lexical items borrowed from lan-

guages other than Chinese. Not surprisingly, the

Japanese borrowed the most words from cultures

with which they had the most contact. Often loan

words reflect borrowed aspects of material culture,

as well as the introduction of new concepts and spe-

cialized terminology. From Portuguese traders and

missionaries, for instance, the Japanese borrowed

such terms as pan (bread, from the Portuguese paõ)

and tempura (battered deep-fried vegetables and

fish, from the Portuguese tempero). After the Por-

tuguese were expelled from Japan in the first half of

the 17th century, Dutch influence predominated.

The Japanese borrowed words not only from

Dutch medical and scientific discourse, but also

such everyday words as biiru (beer, from the Dutch

bier).

H ANDBOOK TO L IFE IN M EDIEVAL AND E ARLY M ODERN J APAN

246

Writing Styles

The history of the varied Japanese writing styles is

complex as a result of the multiple ways of reading

and writing characters and kana. Texts from the

medieval and early modern periods reflected this

diversity of written forms. Some texts were written

in classical Chinese, others used Japanese generously

laced with kanji, while still others reflected a style

using mostly kana. Styles were also combined in

hybrid forms. The following brief list of written

styles is by no means exclusive, but it does reference

the most important.

CLASSICAL JAPANESE

Classical Japanese is a broad term that encompasses

writing in Japanese from the Heian period through

the Edo period. Classical Japanese is especially asso-

ciated with the literary style of Heian-period aristo-

crats. There are, in fact, a number of styles that fall

under this heading, including Japanese poetry that

uses little Chinese vocabulary, prose that uses mostly

Japanese diction, and writing that uses both Chinese

vocabulary and occasional applications of Chinese

syntax in otherwise Japanese sentences. From a con-

temporary perspective, any writing in Japanese prior

to about 1900 can be considered classical Japanese.

The Heian-period style of classical Japanese that

used little Chinese vocabulary was, by the start of

the medieval period, undergoing significant changes

as a result of interactions with Chinese. One result

of Chinese influence on Japanese was the develop-

ment of the Japanese-Chinese mixed style (wakan

konkobun) in the medieval period. This writing style

is treated below. In the Edo period, National Learn-

ing scholars (see chapter 7: Philosophy, Education,

and Science), in their attempt to reclaim a pristine

Japanese past cleansed of the taint of foreign influ-

ence, took a special interest in early Japanese poetry

and hence classical Japanese prior to the medieval

period.

L ANGUAGE AND L ITERATURE

247

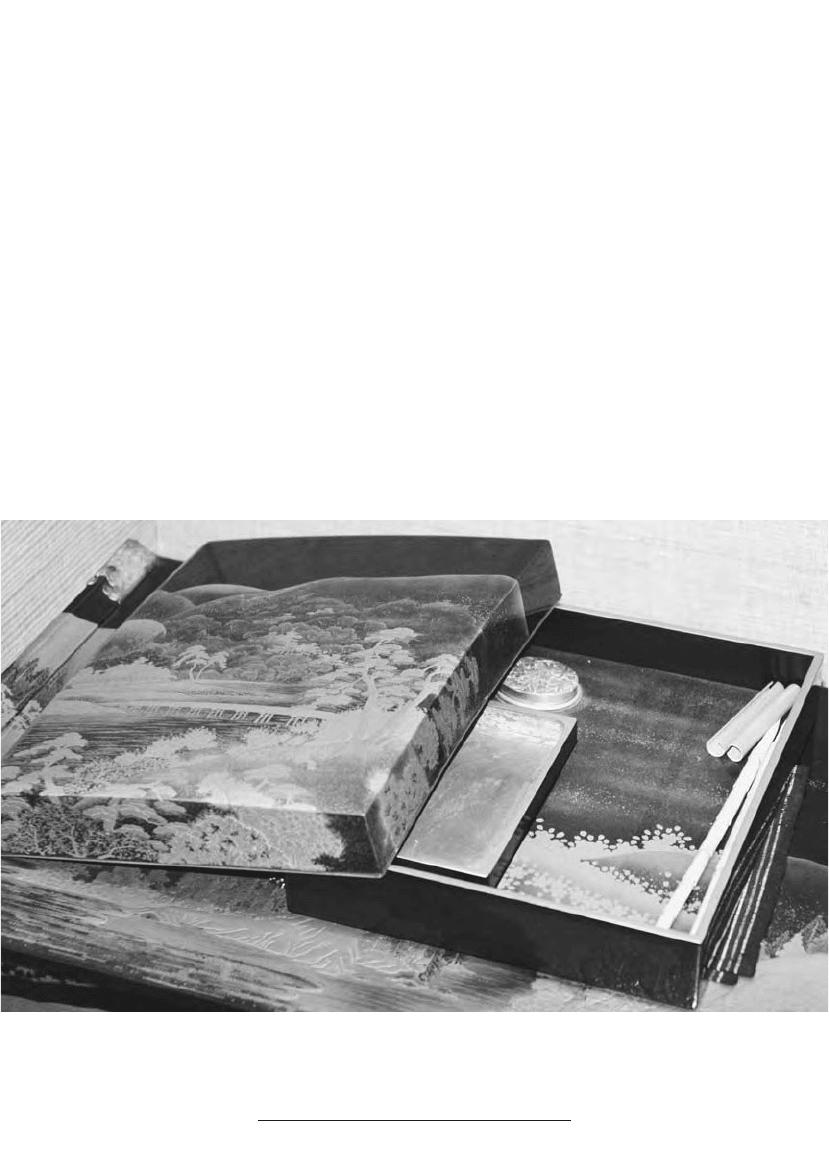

8.1 Writing set, including brush and inkstone (Photo William E. Deal)

It is thought that the classical Japanese of Heian

aristocrats was closely connected to the spoken lan-

guage of the time. By the early modern period,

Japanese as spoken language bore little resemblance

to the spoken language of the Heian period. Hence,

classical Japanese came to be more and more

removed from colloquial speech. In the Edo period,

however, the colloquial speech of the day did find its

way into literature in which dialogue was central,

such as plays and some forms of fiction. Edo-period

vernacular literature, then, is also an aspect of classi-

cal Japanese, but a very different language than, say,

the classical Japanese of Heian poetry and prose.

CLASSICAL CHINESE

Classical Chinese (kambun; literally, “Chinese writ-

ing”) refers to any writings, particularly by Japanese,

composed in Chinese. In the medieval and early

modern periods, classical Chinese was especially

associated with and sometimes used in scholarly and

religious writing. It was also sometimes used as a lit-

erary language. Japanese poetry written in Chinese,

known as kanshi, is one example. The study of classi-

cal Chinese was also central to education in the early

modern period—students were expected to be able

to read and recite passages from the Chinese classics

both to promote literacy and to instill in children

fundamental Neo-Confucian values.

Difficulties in reading classical Chinese were

partly resolved through the Japanese use of a system

of marks that were placed within the Chinese text

and served as pointers on how to read and under-

stand the syntax of a particular Chinese passage.

While Japanese used a subject-object-verb word

order, Chinese used a subject-verb-object word

order. The use of these markings effectively showed

the reader how to render a Chinese sentence in clas-

sical Japanese.

VARIANT CHINESE

Variant Chinese (hentai kambun) refers to a hybrid

combination of both classical Chinese and classical

Japanese. The Japanese had learned to write Chi-

nese (kambun) during the centuries of contact with

the Asian mainland. After ongoing contact ended in

the late ninth century, Japanese writing in Chinese

more and more included such anomalies as Japanese

words, syntactical irregularities, and the misplace-

ment of verbs. While this variant or hybrid form of

classical Chinese might be perfectly understandable

to the Japanese, it would have been peculiar at best,

if not incomprehensible, to the Chinese. It was, in

effect, a writing style that looked Chinese but had

developed into a different language than classical

Chinese.

By the end of the Heian period, variant Chinese

was being used in government documents and in the

conduct of everyday business. In the medieval

period, variant Chinese was used to write a number

of different kinds of documents, including historical

narratives, shogunal records, contracts, and diaries

written by men. Variant Chinese was also used into

the Edo period.

JAPANESE-CHINESE MIXED STYLE

Japanese-Chinese mixed style (wakan konkobun) is,

strictly speaking, a form of classical Japanese. It is a

hybrid writing style that intermingles Japanese and

Chinese character readings, grammar, and lexical

items. Japanese-Chinese mixed style evolved out of

the practice of adding marks to Chinese texts in

order that they could be read more easily by Japan-

ese readers. This style developed in the medieval

period and was used into the Edo period. Classic

examples of compositions in this style are two

Kamakura-period texts, Heike monogatari (Tale of

the Heike) and Hojoki (An Account of My Hut).

EPISTOLARY STYLE

Epistolary style (sorobun) was a formal writing style

in use during the early modern period. As its name

suggests, this style was used for letters—both per-

sonal and official—and also in government-related

documents. The Tokugawa shogunate required that

all correspondence coming into its offices—such as

reports and requests—be written in this style. The

term sorobun derives from the frequent use of the

polite auxiliary verb soro that occurs in this writing

style. The use of this verb served to humble the

writer before the intended recipient—the govern-

ment. Like other Japanese writing styles, sorobun was

a hybrid form. Although it was based on classical

H ANDBOOK TO L IFE IN M EDIEVAL AND E ARLY M ODERN J APAN

248

Japanese, it used many Chinese characters, generally

left out kana used as particles and verb suffixes, and

often placed words in Chinese order.

LITERATURE

Introduction

Japanese literature has a long history dating back

to the early eighth century when the oldest extant

texts were compiled. Literature prior to the

medieval period had been almost entirely the work

of aristocrats. Texts like the Tale of Genji (Genji mono-

gatari, ca. 1000) are suffused with the sensibilities,

values, and aesthetics of Heian-period aristocrats.

While aristocratic literature retained its importance

throughout the medieval and early modern periods,

it was also supplanted in many ways by literature

that reflected the sensibilities of a much broader seg-

ment of Japanese society. Warriors, Buddhists, mer-

chants, masterless samurai, and geisha were among

those who became the subjects of this literature and

those whose interests this literature sometimes

expressed.

Medieval and early modern literature was written

in a variety of different styles, such as classical Japan-

ese, Japanese-Chinese Mixed Style, and Variant

Chinese. Literary sensibilities found expression in

such textual genres as poetry, fiction, drama, literary

theory, diaries, travel accounts, and journal-style

writings. Within these genres, there were many

different styles, such as the various kinds of poetry—

for instance, haiku and linked verse—and prose

writings—such as war tales and travel diaries.

The following discussion examines medieval and

early modern literature in historical perspective. It

should be noted that drama and other writing for

theater is not treated in this chapter for two reasons.

First, theater, including influential plays and play-

wrights, is treated in chapter 9: Performing Arts.

Second, the idea that plays were literature was

mostly a foreign idea in medieval and early modern

Japan. Plays were first and foremost an art to be per-

formed and observed. The texts of Kabuki plays

were not usually even published. Thus, to discuss

drama here might be in keeping with contemporary

sensibilities, but it would not reflect how theater was

consumed by the Japanese in the medieval and early

modern periods.

Medieval Literature

MEDIEVAL POETRY

Waka At the beginning of the medieval period,

waka poetry, so closely associated with Heian-period

aristocrats, was still a vibrant literary art. Waka

(“Japanese poem”), also referred to as tanka (“short

poem”), is verse that is composed of five lines with a

total of 31 syllables in a 5-7-5-7-7 pattern. Despite

the transformation of Japan into a country in which

warrior values were newly ascendant, poetry re-

mained a central mode of expression for aristocrats

and, often, well-educated Buddhist priests. This

is evidenced by the 15 imperial poetry anthologies

that were compiled during the medieval period. Fur-

ther, the poetry included in these anthologies fol-

lowed the poetic rules set down during the Heian

period.

Medieval waka did not express warrior values—it

was still very much an aristocratic art. But the tur-

moil of the Gempei War and the decline of the

political and social influence of the court was

reflected in the darker mood and tenor of some

medieval waka. The Buddhist notion of mappo, “the

end of the Dharma,” asserted that the world had

entered an era of spiritual darkness and confusion.

No doubt the period of civil war that ushered in the

medieval period contributed to the belief in the

veracity of this view. Buddhism also taught that life

is transient and that human fortunes are ephemeral.

This sense of the fundamental impermanence of

human existence was expressed by some aristocrats

and Buddhists through waka.

In the early Kamakura period, Fujiwara no Shun-

zei (or Toshinari, 1114–1204) and his son, Fujiwara

no Teika (or Sadaie; 1162–1241), were among the

most outstanding poets. Shunzei conceived of waka

composition as a spiritual practice analogous to

L ANGUAGE AND L ITERATURE

249

meditation. For him, composing waka was a way to

attain enlightenment if practiced with “concentra-

tion and insight” (shikan), a Tendai school form of

meditation. Both Shunzei and Teika set the aesthetic

tone for Kamakura-period waka. They promoted

the notion of “traditional language, fresh concep-

tions” (kotoba furuku, kokoro atarashi) in which the

language of traditional waka was used in new ways.

Innovative language, however, had to express the

aesthetic ideal of yugen, “mystery and depth,” that

was both a literary and spiritual goal aspiring to ele-

vate the prosaic into a profound beauty. They also

prized the use of honkadori, a technique whereby the

poet alludes to an earlier poem and then develops

this imagery in new ways.

These poetic ideals found expression in the

eighth imperial anthology, Shin kokinshu (New col-

lection of poems from ancient and modern times)

that was compiled by Teika and others around 1205.

The Shin kokinshu was commissioned by retired

Emperor Go-Toba whose poetry also appears in the

collection. Other prominent Shin kokinshu poets

include Teika, Shunzei, Fujiwara no Yoshitsune

(1169–1206), Princess Shokushi (d. 1201), Fujiwara

no Ietaka (1158–1237), and the Buddhist priests

Saigyo (1118–1190) and Jien (1155–1225). This col-

lection is widely regarded as containing the finest

waka of all medieval imperial poetry anthologies.

Renga Although waka continued to be written, by

the time the last imperially commissioned waka

anthology was compiled in 1439, the creativity of

this poetic form was already moribund. In part, waka

was a victim of its own poetic rules for how a poem

was to be composed, including the kinds of imagery

that were permissible. As a result, medieval poets

eschewed the rigidity of waka for the new poetic

possibilities of linked verse (renga). Between the

13th and 16th centuries, the best poets composed in

the renga style.

The structure of renga is similar to waka but the

poem created is the work of more than one poet

composing a sequence of consecutive verses. In

waka, one poet creates a 31-syllable verse of five

lines in a 5-7-5-7-7 syllable structure. In renga, a

poet composes the first three lines (5-7-5) and a sec-

ond poet composes the last two lines (7-7). By con-

tinuing this process, a long chain of alternating

5-7-5 and 7-7 lines is created. There was variability

in the number of lines that constituted a linked verse

sequence, but over time the standard length was set

at 100 stanzas.

Lines of verse are linked to each other through

associative word imagery and subject matter. For

instance, a poet might start with a verse about a

cuckoo, a bird that symbolizes summer. The next

poet might introduce the image of a pine tree which,

in Japan, has poetic associations to the cuckoo. The

Japanese word for pine (matsu) is also a homophone

for the verb “to wait,” a reference to waiting or

anticipating some event or action. The next poet,

expanding on the pine tree image, might create a

verse calling to mind a shady mountain scene with a

stream flowing through it. Pine trees are connected

to mountains, and both mountains and the heat of

summer are relieved by the mountain shade and the

cool flowing stream. A fourth poet might then intro-

duce the idea of a moonlit scene because other

Japanese imagery speaks of the Moon reflected in

H ANDBOOK TO L IFE IN M EDIEVAL AND E ARLY M ODERN J APAN

250

8.2 The late Heian–early Kamakura poet-priest Saigyo

(1118–90)

(Illustration Kikuchi Yosai from Zenken

kojitsu, mid-19th century)

water. The Moon symbolizes autumn; hence, this

linked sequence moves from summer to fall.

The idea of two poets composing a single waka

dates to the Heian period when the communal com-

position of a 31-syllable poem was a leisurely pas-

time. In the Heian practice, one poet composed the

first three lines and another poet the second

two lines, creating what is sometimes referred to

as a “short” renga. This practice was expanded in the

medieval period and much longer links were pro-

duced, the result of several poets working together.

By the 14th century, renga had become a serious

poetic style that eclipsed waka in importance. In

1356, Nijo Yoshimoto, a high-ranking Kyoto aristo-

crat, compiled the Tsukuba shu (Tsukuba Collection;

the title is a reference to a Manyo’shu poem), a

collection that secured for renga its status as a legiti-

mate literary art form. Yoshimoto’s successors fur-

ther advanced the reputation of renga. Of particular

note are the two renga masters, Shinkei (1407–75)

and Sogi (1421–1502).

Shinkei, a Buddhist priest, was not only a highly

regarded poet, but he also wrote theoretical treatises

on the nature of poetry in general and renga in par-

ticular. Not unlike Fujiwara no Shunzei’s view of

waka, Shinkei found a deep connection between

poetry composition and the religious quest for

enlightenment. For Shinkei, pursuit of poetic ideals

was deeply spiritual because it held the possibility of

profound expression about the nature of the world.

The aesthetic ideal of yugen (mystery and depth) was

central to the spiritual possibilities of poetry compo-

sition. Shinkei’s Sasamegoto (Whisperings, 1463) dis-

cusses his views of renga and its relationship to yugen

and other aesthetic ideals.

Sogi, also a Buddhist priest, was an accomplished

poet. He came from a commoner background, so his

poetry was informed not only by the refined sensi-

bilities of Kyoto poets but also by the lives of peas-

ants and farmers. Sogi exemplified the communal

nature of renga and the necessity of working closely

with other poets to create a coherent series of linked

verses. In 1488 Sogi traveled to Minase shrine, in a

village between Kyoto and Osaka, to compose a

renga sequence with two other renga masters,

Shohaku (1443–1527) and Socho (1448–1532). The

result of this collaboration was the 100-verse renga

composition titled Minase sangin hyakuin (One hun-

dred links by three poets at Minase), arguably the

finest example of the genre. The success of this text

stems from its ability to create a flow of associative

word imagery and subject matter.

MEDIEVAL PROSE

Diaries The medieval period continued the tradi-

tion of diary writing begun in the Heian period. As

in that period, many significant medieval diaries

were composed by aristocratic and Buddhist women.

The term diary is somewhat misleading, however,

because diaries were not necessarily daily or weekly

accounts written as events occurred. Rather they

were often memoirs, recollections, accounts of one’s

travels, or a combination of these, and many also

included poetry. To further complicate matters, the

term diary has also been applied to fictional stories

written in the form of diaries.

Travel diaries are sometimes treated as a separate

genre, but this is problematic because travel diaries

can include memories and recollections. There are

also different kinds of travel diaries, such as those

that recount pilgrimages to sacred places and

accounts of travel from Kyoto to the shogunate at

Kamakura to deal with legal matters. Diaries were

also written by poets about their journeys in the

countryside often to visit places associated with

famous poems of the past. Poetry is typically inter-

spersed with prose in such accounts. The famous

renga poets Sogi and Socho both wrote poetic travel

diaries in the Muromachi period.

Some representative medieval diaries include:

K

AIDOKI

(JOURNEY ALONG THE SEACOAST ROAD, 1223)

Written by an unknown man, this travel diary

recounts the author’s walking trip from Kyoto to

Kamakura visiting famous sites along the way.

K

ENREIMON’IN UKYO NO DAIBU NO SHU

(POETIC MEMOIRS OF LADY DAIBU, CA. 1231)

Kenreimon’in ukyo no daibu (ca. 1157–unknown),

or Lady Daibu, was an aristocratic woman who

served in the court of Emperor Go-Toba. Her mem-

oir is a particularly interesting glimpse at the life of

an aristocratic woman connected with the Taira

family—the vanquished clan of Gempei War fame—

L ANGUAGE AND L ITERATURE

251

whose lover, Taira Sukemori, was killed at the Battle

of Dannoura in the closing battle of the Gempei

War in 1185.

B

EN NO NAISHI NIKKI

(DIARY OF LADY BEN, CA. 1260)

Composed by the aristocratic woman Go-Fukakusa

In Ben no Naishi (dates unknown), who was in ser-

vice at the court of Emperor Go-Fukakusa, this

diary records events that occurred at court during

Go-Fukakusa’s reign.

I

ZAYOI NIKKI

(DIARY OF THE WANING MOON, 1280)

Composed by the Buddhist nun Abutsu (d. 1283),

this diary relates events connected with her journey

from Kyoto to Kamakura to press her claim about a

property dispute in the shogun’s courts.

T

OWAZUGATARI

(THE CONFESSIONS OF LADY NIJO, 1313)

This diary of Go-Fukakusa In no Nijo (1258–

unknown), an aristocratic woman who served in

the court of Emperor Go-Fukakusa, is commonly

known as The Confessions of Lady Nijo in English

translation. However, the literal meaning of the title

is “A Tale Nobody Asked For.” This diary recounts

Lady Nijo’s numerous love affairs and her eventual

dismissal from service to the court. She talks about

her decision to take the tonsure and become a Bud-

dhist nun. She then embarks on a number of jour-

neys that she describes in detail.

I

SE DAIJINGU SANKEIKI (ACCOUNT OF A

PILGRIMAGE TO THE GREAT SHRINE AT

ISE, 1342)

This travel diary by the Buddhist priest Saka Jubutsu

records his pilgrimage to the Shinto sacred site, the

Ise Shrine, in 1342. This diary is especially interest-

ing because of the view it provides of the relationship

between Buddhism and Shinto in the 14th century.

T

SUKUSHI MICHI NO KI (JOURNEY ALONG

THE

TSUKUSHI ROAD, 1480)

Sogi (1421–1502) was a noted renga poet and trav-

eler. His diary, Journey along the Tsukushi Road,

recounts his journey to Kyushu, visiting places of

historic and poetic significance along the way, and

interspersing poetry with his prose.

U

TSUNOYAMA NO KI

(ACCOUNT OF UTSUNOYAMA, 1517)

Like his friend Sogi, Socho (1148–1532) was a noted

renga poet and traveler. His diary, Account of

Utsunoyama, is both memoir and a recollection of

his travels to sites of historical and poetic interest.

Essays “Essay” refers to the genre known in Japan-

ese as zuihitsu (literally, “following the writing

brush”). These are miscellaneous essays or random

thoughts—often personal observations about people

and nature—set down with no particular structure in

mind. Two classic examples of this genre are also

among the most important literary works from the

Kamakura period: Hojoki (An Account of My Hut,

1212) by Kamo no Chomei (1155–1216) and Ts u-

rezuregusa (Essays in Idleness, ca. 1330) by Kenko

(Yoshida Kaneyoshi, ca. 1283–ca. 1352). The

authors were both Buddhist recluses, having left

behind a world in a state of social and political tur-

moil. For Kamo no Chomei, the unsettled time

period was the Gempei War (1180–85) and its after-

math; for Kenko, it was the political intrigue and

warfare that occurred at the transition from the

Kamakura and Muromachi periods.

Both of these works are imbued with the Bud-

dhist idea of impermanence (mujo), according to

which the world is a place of constant change and

instability. Both Kamo no Chomei and Kenko find

abundant evidence for the truth of this view in their

descriptions of the world they inhabit. They also

both raise questions about the nature of enlighten-

ment and its possibility in such a tumultuous world.

In the Hojoki, Chomei reveals his acute awareness of

impermanence and the transience of human exis-

tence. He also conveys his satisfaction at living a

simple, reclusive life. In the Tsurezuregusa, Kenko

reflects on the human condition and poignantly

recalls happier days now long past. Occasionally,

Kenko also assumes a moral tone in his reflections

on life and living.

War Tales War tales (gunki monogatari), composed

during the Kamakura and Muromachi periods,

became a very popular literary form. These tales

narrated stories of great conflicts and battles, and

described in detail the heroic victories and defeats of

the greatest warriors. Such stories also became the

H ANDBOOK TO L IFE IN M EDIEVAL AND E ARLY M ODERN J APAN

252

source for later literary and theatrical forms, includ-

ing the recitation of tales by itinerant biwa musicians

(biwa hoshi) and the dramatization of warrior exploits

in Kabuki and Bunraku dramas. War tales not only

reflected the interests of the ruling warrior class, but

they also framed a warrior ethic that, by the Edo

period, became codified as part of the way of the

warrior (bushido). Prized warrior values included

bravery, loyalty, duty to one’s lord, and a heroic

death. A list of some of the more important war tales

follows below. Special attention is given to the Heike

monogatari (Tale of the Heike), widely regarded as the

classic and best example of this literary genre.

Some representative medieval war tales include:

H

OGEN MONOGATARI (TALE OF THE HOGEN

DISTURBANCE, CA. EARLY 13TH CENTURY)

The Hogen monogatari recounts the events and

armed conflict that occurred in 1156 when the

retired emperor Sutoku made an unsuccessful

attempt to gain control of imperial power against

the current emperor, Go-Shirakawa.

H

EIJI MONOGATARI (TALE OF THE HEIJI

DISTURBANCE, CA. EARLY 13TH CENTURY)

The Heiji monogatari recounts the events and armed

conflict that occurred in 1156–60, in Fujiwara

Nobuyori’s failed attempt to seize power from the

Taira family.

H

EIKE MONOGATARI (TALE OF THE HEIKE,

FIRST HALF OF THE 13TH CENTURY)

The Heike monogatari recounts the political intrigue,

battles, heroics, and other events that occurred

before, during, and after the Gempei War (1180–85)

between the Taira (or Heike) and Minamoto (or

Genji) warrior families (see chapter 1: Historical

Context, for details on the Gempei War). The Heike

story focuses on the ascent of the Taira warrior clan to

power in the waning years of the Heian period, their

control of the imperial court, and their eventual fall

and defeat at the hands of forces led by the Minamoto

clan. Many classic Japanese stories of bravery, loyalty,

self-sacrifice, and honor in defeat derive from the

Heike monogatari. It is arguably the most important of

all the war tales, and certainly the one that gave defin-

itive shape to the war tale genre. This tale became

widely known across all social classes by virtue of the

many literary and theatrical genres used to narrate the

Heike monogatari’s stories. Notable among these were

the oral recitations of the Heike story by itinerant

biwa players during the medieval period.

There are two important Buddhist themes that

set the tone for the entire work: impermanence and

karmic retribution. The famous opening lines of the

Heike remark on the impermanence (mujo) of the

world and the fleeting nature of human existence, a

sensibility repeated throughout the text. The notion

that all things necessarily perish foreshadows the

inevitable downfall of the Taira family from power.

The cause of their fall is not fated, but is rather a

direct result of karmic retribution, that is, retribu-

tion for evil actions. The Buddhist view is that all

actions, good and bad, have a positive or negative

consequence. The arrogance and ruthlessness of the

Taira result in a downfall that is both deserved and

inescapable.

A sensibility expressed in the Heike monogatari

that tends to run counter to Western values is the fo-

cus on the defeated rather than the victorious. There

is a strong sense of tragedy and sadness that pervades

the Heike’s account of the Tairas’ downfall. Sympa-

thy for the defeated, fueled in part by the Buddhist

virtue of compassion, tempers any negative evalua-

tions of the Taira.

One interesting theory concerning the early

development of the Heike monogatari asserts that

there may have been a ritual aspect to the early oral

recitations of the events that later became the Heike

text. There existed in Japan a tradition of chanting

Buddhist texts as a way to pacify the souls of the

dead that might otherwise wreak havoc on the liv-

ing. The chanting of the Heike text may have been

intended to pacify the souls of those who had died in

the Gempei War.

G

EMPEI SEISUIKI (AN ACCOUNT OF

THE

GEMPEI WAR, EARLY 14TH CENTURY)

The Gempei seisuiki (or josuiki), like the Heike mono-

gatari, recounts the battles, heroics, and other events

that occurred before and during the Gempei War

(1180–85) between the Taira (or Heike) and

Minamoto (or Genji) warrior families. Unlike the

Heike monogatari, which developed originally out of

an oral storytelling tradition, the Gempei seisuiki

developed from the first as a written narrative.

L ANGUAGE AND L ITERATURE

253