Cornwall M. The Undermining of Austria-Hungary: The Battle for Hearts and Minds

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

364 The Undermining of Austria-Hungary

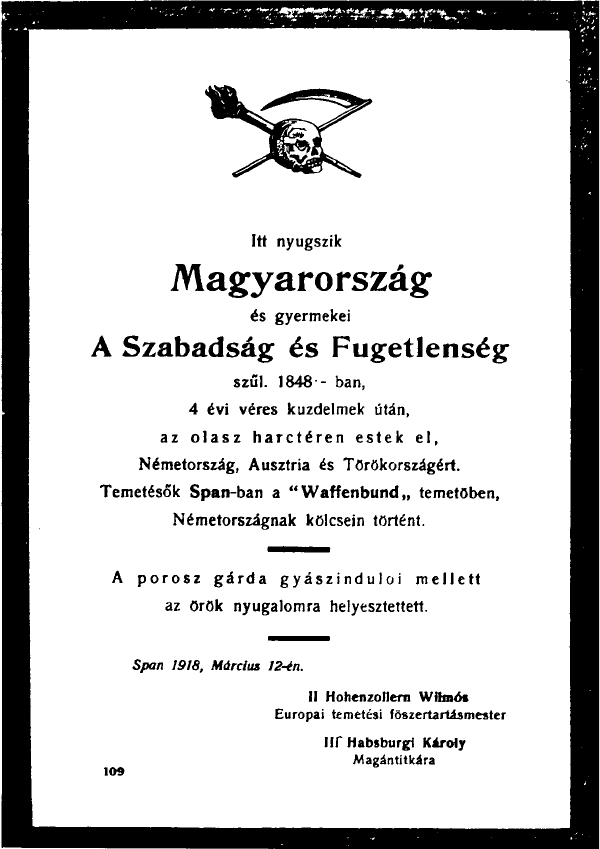

Illustration 8.4 Manifesto 109: The death of Hungary is announced (KA)

Austrian commanders and called for them to be investigated.

200

As a fellow

deputy sarcastically observed, instead of being properly punished Conrad

von Ho

È

tzendorf

had been created a Count after the battle, whereas `somebody

who gets married at the age of 64 is more fit to be put into care'.

201

Padua

duly agreed that the Magyars had been pure cannon-fodder: `The Germans

The Climax of Italian Psychological Warfare 365

and Austrians like a bankrupt stock-exchange speculator are trying to save their

own future, at the cost of your blood and national existence, spending it as if it

were money

obtained by theft or fraud.' In the past the Hungarian attitude had

been different:

Peto

Â

Â

fi's

great poem `Talpra Magyar' was declaimed, and every true Magyar

rushed to the frontiers to fight for liberty and against tyranny. But nowadays

in a four-year long bloody war the noble and free Magyar nation is falling

and perishing, and not in order to fight an enemy that threatens its hearth

and freedom.

202

On the contrary, it was Italy and her allies who were fighting in the spirit of

Kossuth and Garibaldi for freedom, peace and independence for all nations.

This, Padua implied, meant freedom for the Magyars too: freedom from the

German and Austrian yoke, and freedom to establish their own independent

Hungarian state.

203

The second key point of attack in Padua's Magyar material was against the

landowning elite of Hungary, who, in league with Vienna and Berlin, were said

to be exploiting the Hungarian masses. It was an argument, the legitimacy of

which was to be queried but approved at the inter-Allied propaganda confer-

ence in

August, but Ojetti had already been using it effectively well before that

date.

204

Since the early summer witnessed a general strike in Hungary, as well as

the climax of the wartime struggle for electoral reform, Padua had fertile soil to

plough. As usual, its main source of information was the radical and socialist

Hungarian press. Indeed, Crewe House may well have managed at this time

to insert its own articles into Vila

Â

g and other papers through the agencies of

S.A. Guest and

possibly the Vila

Â

g correspondent in Switzerland.

205

Padua's

manifestos detailed the miserable situation of civilians in Hungary, where

corrupt officials and profiteers were rife, where mothers were told to cut their

children's throats if they could not feed them, where even Budapest now

looked `incredibly dreary and bare'; if previously only newspaper vendors had

called out in the streets of the city, now it was the empty shop windows which

cried out with hunger. The exorbitant prices for basic commodities were

destroying the families of Hungarian soldiers, but the situation was simply

condoned by a `tyrannical government' which had nothing but contempt for

working people:

The demonstrations

of the working masses draw today only regretful and

disdainful smiles from the faces of the ministers . . . The feudal and capitalist

reactionaries, who reached the peak of their power during the war, have in

all walks of political and economic life pitilessly and slyly brought Hungar-

ian social

democracy to the grave.

206

366 The Undermining of Austria-Hungary

This manifesto 288 was one of the few issued by Padua on the subject of social

democracy in Hungary, an indication that the Allied propagandists always

shied away from openly supporting socialist (as opposed to nationalist) parties

in the Monarchy, even if there was clear ambiguity in their regular use of

Arbeiter-Zeitung. The manifesto quoted had somewhat reinforced an earlier

leaflet which had made use of Ne

Â

pszava, the radical SD newspaper. Writing at

the height of the mass strike in Budapest, Ne

Â

pszava had called for the resigna-

tion of

the `dishonest and reactionary' Hungarian government which had

`never been that of the toilers of the fields but rather a government of the

landowners . . . It has stood in the way of democracy in a guilty fashion and in

the way of the social policy promised by the King.'

207

But if the Prime Minister, Sa

Â

ndor Wekerle, and his government had irretriev-

ably compromised

the country's interests, they were, according to Padua, no

more than an `automatic toy' in the hands of the real culprit, Count Istva

Â

n

Tisza. As Arbeiter-Zeitung observed, Tisza was still protecting the `rights' of the

agrarian elite, the rights for which Hungary had gone to war and sacrificed so

much, for he had managed to prevent the degree of electoral reform demanded

by the parliamentary opposition and promised by Karl in 1917.

208

Padua

explained that Tisza

knew very

well that once the people have got the right to vote they would

sweep him and his miserable flunkies away. He can only rule over slaves, and

it is his obsession always to remain in power. He therefore brought down the

Esterha

Â

zy government [September 1917] and helped Wekerle into the Prime

Minister's chair so that he and his party could dictate, cunningly and invis-

ibly, to

the cowardly Wekerle from behind the scenes, the Viennese and

Berlin lessons for your complete disenfranchisement. So the bill for the

extension of the franchise has failed, and in its place an Act of Slavery has

been passed.

209

The reactionary count had thereupon departed for the Italian Front, a move

which produced more derisory comments from Arbeiter-Zeitung on 25 July:

For many

months Tisza has fought in his own fatherland with the rank of

a colonel against the new franchise programme. Now he has gloriously

finished the fight on the electoral front and his courage, which knows no

bounds, has egged him on to new battles. Tremble O Italians!

Ironically, this

particular leaflet, which ended with a reminder that `the fight

which Tisza is in the process of winning is directed not against Italy but against

you', seems to have been one which Tisza himself came across during his short

stay in the Italian theatre in the summer.

210

It was a type of propaganda which

The Climax of Italian Psychological Warfare 367

the Padua Commission seems to have viewed as successful, responsible accord-

ing to

Granville Baker for an increase in desertions by lower-class Hungarian

soldiers.

The number

of manifestos directed at German-Austrians also increased dur-

ing the

summer but, with 26 texts in three million copies, it was still less than

10 per cent of the total produced in these months and half of that directed at

the Magyars. Under Ojetti's firm control, it was written largely by the `phenom-

211

enal polyglot' Stojan Lasic

Â

. It tended to contain only the more general

demoralizing arguments present in Padua's other propaganda, namely the

strength of Allied forces, their successes in battle or in sinking the Austrian

dreadnought Szent-Istva

Â

n; the abundance of food in Italy compared to the

hunger and misery among civilians in Austria.

212

Only a few appeals were

made to German-Austrian soldiers on the express basis of their separate nation-

ality or

identity (notably that they were fighting for Germany's interests), even

though the idea of doing so was certainly mooted by some of the Allied

propagandists.

On 6

August there was a discussion at Crewe House about a memorandum by

a French journalist, Marcel Ray, who had had talks in Zurich with a Dr Friedrich

Hertz of Vienna. Ironically, and unbeknown to the British EPD, Hertz had been

giving some lectures on FA courses in Austria. But he had told Ray that he was

particularly worried about Austria becoming a mere vassal of Germany, suggest-

ing to

him that, with the aid of the Entente, he might set up an anti-Prussian

organization which would issue not revolutionary or defeatist material but

positive propaganda to turn German-Austrians against the German Empire.

The idea seems to have appealed to Crewe House, but it is unclear whether it

was pursued further.

213

Possibly one of Hertz's opinions, that the West should

not issue revolutionary material, had some influence upon a decision made at

Northcliffe's propaganda conference, that the Allies would only circulate the

Austrian proletariat's literature and not produce `Bolshevik propaganda' of

their own. Such distribution, if it occurred, would have been carried out

through secret channels from Switzerland, where one British diplomat noted

at this time: `we now have admirable means for supplying material from

Switzerland, even in bulk, to Vienna and elsewhere in the Dual Monarchy

[but] the present difficulty is distribution'.

214

In contrast, on the Italian Front,

there was little sign of the Allies spreading any socialist propaganda.

Indeed, only

a few of Padua's German manifestos directly attacked the rulers

in Vienna, warning for instance that the West, though very keen to make peace,

would only do so with the German people, not with the absolutist regimes of

Vienna and Berlin. German-Austrians were urged, like the Magyars, to throw off

the `medieval despotism' which governed Austria, where archdukes, great

property owners and others were enriching themselves at the expense of the

state and of those starving in the trenches.

215

Otherwise, the message was to be

368 The Undermining of Austria-Hungary

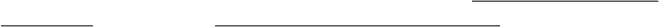

Illustration 8.5 Manifesto 228: Austria's identity papers are marked `Unscrupulousness',

`Slovenliness' and `Hunger' (KA)

one of despair. Austria was most vividly portrayed as a `hideous and dirty old

hag' who had three different names on her identity papers: `unscrupulousness',

`slovenliness' and `hunger'. This was not an image invented by Padua, but one

taken directly from a cartoon in the Viennese satirical journal Die Muskete;

ironically, the AOK had already used this paper as a source of propaganda for

The Climax of Italian Psychological Warfare 369

its own campaign against Italy. Padua now reproduced one of the journal's title

pages with the cartoon and a suitable commentary. A copy of the leaflet duly

found its way to the FAst in Vienna which immediately warned the editors of

Die Muskete: `it shows how enemy propaganda knows how to pick up any clues

from our press and use them to its advantage'.

216

The Padua Commission's most notable appeal to the German-Austrians,

however, and probably the most celebrated deed of the whole campaign, was

the propaganda flight made over Vienna on 9 August by the legendary poet-

adventurer, Gabriele D'Annunzio. Already in August 1915 this modern-day

Aeschylus had scattered messages of encouragement to the populations of

Trieste and Trento, and later in the year had first mentioned the idea of a

dramatic flight to Vienna itself. Two years later such a plan was technically

feasible, for in September 1917 D'Annunzio made a successful nine-hour

test flight over a thousand kilometres of Italian territory, and proceeded to

think of bombing the palace at Scho

È

nbrunn

as well as broadcasting con-

temptuous messages

to Vienna's inhabitants.

217

But only by the summer of

1918 was the CS receptive to the idea. By then, the 87th squadron, established

in February to carry out bombing raids deep in the Austrian hinterland,

had made its successful propaganda flights over Ljubljana and Zagreb: a

similar expedition to Vienna was viewed by the Padua Commission as the

next logical step.

218

Indeed, the flight on 9 August was not just, as the Corriere della Sera asserted

the next day, `a gesture of heroism and magnanimity' to prove Italian super-

iority over

the enemy. It was also very much an integral part of Padua's overall

campaign. After Diaz had approved the idea, apparently through pressure from

D'Annunzio, Ugo Ojetti had sat down on 24 June to write the manifestos.

219

The first, manifesto 128, with the text printed over a colour picture of the

Italian flag, reminded the Viennese that instead of bombs the planes were

bringing them `a greeting of the tricolour of freedom' since Italy was not fight-

ing Austrian

civilians but the Austrian government, the `enemy of national

freedom'. As Ojetti told his wife, he did not want to throw out insults when

addressing civilians, but simply to `show our moral stature and a little of our

appeal'. The leaflet, after warning that the absolute victory promised by the

Prussian generals was as illusionary as bread from Ukraine, ended with cries of

exaltation for freedom, Italy and the Entente.

220

Ojetti's second manifesto set

out the Allies' political vision and was of more substance. It condemned the

unjust `Prussian peaces' of Brest-Litovsk and Bucharest, urging the Viennese to

shake off Germany; all of Italy was now united, and was joined by the whole of

the civilized world in fighting in the mid-nineteenth-century Italian spirit for

the freedom of all nations. The Viennese should remember 13 March 1848,

when their cries for liberty were echoed in Paris, Venice and Milan, and liberate

themselves.

221

370 The Undermining of Austria-Hungary

The two manifestos were approved by Orlando and Diaz (the latter in fact

wanting to submit a tactless leaflet of his own composition), and to them was

added a third, personally composed by D'Annunzio in Italian. It proclaimed in

exotic language that the Italian planes were the sign of an approaching destiny,

of certain victory for the Allied Powers.

222

D'Annunzio himself was determined

to be a member of the propaganda flight, but otherwise it was composed of 11

experienced pilots of the 87th squadron, many of whom had already taken part

in raids on Innsbruck, Ljubljana and Zagreb. At 5.50 a.m. on 9 August, after a

week's delay because of bad weather, the squadron of Capronis took off from

Padua to travel across over 800 kilometres of enemy territory. They were

equipped with leaflets and photographic equipment but no bombs because of

fear of reprisals. Three of the squadron had to turn back very quickly because of

engine trouble. One was forced to land near Wiener Neustadt. But at 9.20 a.m.,

seven of the planes reached Vienna, showering the population with 150 000

manifestos.

Although the

Austrian authorities had some prior warning that a raid would

be made on Vienna, the actual event took them completely by surprise.

223

It

was especially embarrassing for those responsible for air defence in the hinter-

land that

enemy planes, having crossed the front, were able to reach the capital

with so little inconvenience. While the squadron had been aided by a thick

band of cloud between Graz and Wiener Neustadt, its progress was also eased by

the incompetence of local air defence officials. One particular sinner, Lt Oskar

Schlosser, who supervised air defence at Bruck an der Mur, had taken more than

two hours to report the squadron to military authorities at Graz as he thought

that it `could be' Austrian. By this time the flight was already over Vienna, and

although at 9.30 a defence squadron was launched from Wiener Neustadt, it

failed to intercept the Italians who were only fired at over Ljubljana on their

return journey to Padua.

224

The presence of Italian planes over Vienna aroused curiosity and excitement

among the inhabitants rather than fear. According to one observer, who was

peering at the aircraft through opera glasses, the Viennese gathered at windows,

on roofs and in the street, and generally acted contrary to official instructions

about the proper behaviour on such an occasion.

225

The police, in agreement

with the military, immediately began to collect and destroy the manifestos,

conducting widespread searches, for example in a home for refugees which they

believed to have been a special target of the aviators since it allegedly housed

some suspicious Italian characters.

226

The FAst meanwhile promptly told the

AOK that the manifestos were `extraordinarily harmful to the morale of less

sensible people'; it sensed that they probably stemmed from the `Czechoslovak

section of Italian propaganda' and might even have been smuggled into Austria

and distributed by rascals of the Austrian airforce itself (!). As counter-measures,

the FAst recommended censorship of all reports in the Austrian press, and the

The Climax of Italian Psychological Warfare 371

immediate distribution over Vienna of a red `counter-leaflet' urging the popu-

lation to

remain true to their fatherland and their allies in the face of a

treacherous enemy which, having failed to win the war by arms, had now

resorted to a `poison of lies and deceit'. Such a leaflet was never produced, but

the authorities did try to ensure that newspapers toed the official line and

reproduced manifesto 128 only with a suitable commentary.

227

The loyalist

Neue Freie Presse duly obliged, writing that the behaviour of the Viennese had

been `really splendid' with no sign of panic; the Italian appeals were generally

to be scorned and the whole incident dismissed: `The Italians' propaganda

flight can indeed, apart from the political motives lying behind it which are

obviously intended as a substitute for the lack of military success in Albania, be

declared as a sporting exercise of no significance.'

228

Despite this, the authorities were anxious to avoid a repeat performance. On

13 August the Minister of War, General Sto

È

ger-Steiner,

decided that captured

enemy pilots who had distributed propaganda which incited civilians against

the state would, as in the war zone, be put on trial for a crime which carried the

death penalty. This idea worried the Foreign Minister, Count Buria

Â

n, who

feared the international repercussions. Already Buria

Â

n had been concerned

when the AOK had publicized the execution of captured Czech legionaries

after the June offensive, fearing that the Italians would simply turn on their

Austrian prisoners.

229

Sto

È

ger-Steiner

therefore convened a meeting at the War

Ministry for 28 August. There it soon became clear that while the Ballhausplatz

held one view and the AOK the opposite (namely that the law should be

tightened), the War Ministry itself was anything but united over what needed

to be done. Consequently, to the AOK's annoyance, Sto

È

ger-Steiner's

original

decision was revoked.

230

The authorities contented themselves with tightening

hinterland defences against future enemy air attacks, especially in Budapest

which it was feared might well be the next target. In fact, just as an Austrian

counter-raid on Rome appears to have been abandoned due to technical diffi-

culties, so

a second propaganda flight which D'Annunzio was indeed dreaming

of making over Budapest failed to materialize.

231

The Vienna raid was destined

to be an isolated exploit of Padua's campaign, but one which, if nothing else,

had alarmed and further demoralized the Austrian authorities.

If the

Padua Commission could feel suitably elated, announcing to troops

opposite that `it had seemed an impossibility but it became a reality',

232

it was

elation which concealed Ojetti's real frustration with the Italian airforce. His

campaign depended on mass distribution from the air, usually by Italian planes

although by August the British too were undertaking some propaganda

flights.

233

He was trying to average 500 000 leaflets per day.

234

But from late

August this could not be maintained, partly due to bad weather in the last

two months of the war, partly the result of tensions with the Italian airforce.

Already during the Piave offensive both Ojetti and Marchetti had despaired that

372 The Undermining of Austria-Hungary

the aeronautical command under General Luigi Bongiovanni did not attach the

same importance to propaganda raids as to bombing raids. In early July, with

the help of Badoglio, Ojetti had secured from Bongiovanni an equalizing of

propaganda and bombing flights which continued fairly smoothly for the next

two months. By September, however, Ojetti was again to find that the airforce

was deviating from the arrangement and only distributing 90 000 manifestos

per day; again it required Badoglio's intervention before Bongiovanni would

agree with Padua to try to issue a daily minimum of 300 000.

235

Nor was this

Ojetti's only distribution problem. A further irritant, resulting from official

Italy's ambiguous policy, was the fact that the naval authorities under Thaon

di Revel, a supporter of Sonnino, still refused to distribute Padua's Yugoslav

manifestos over the Dalmatian coast. Thaon would only agree to throw out

such material over the naval bases at Pula and Cattaro and over Austrian troops

in Albania, while reserving for Dalmatia his own propaganda in Italian,

especially `suitable' newspapers such as the Sonnino-mouthpiece Giornale

d'Italia.

236

Despite Ojetti's protests to Orlando about this, including the usual

threat of resignation, the naval authorities continued to act largely independ-

ently of

the Padua Commission and certainly did little to further the Yugoslav

cause in Dalmatia.

237

The Austrian authorities remained oblivious to these spanners in their

enemy's propaganda machine. For them, the threat appeared to be increasingly

serious and ubiquitous, seeping across the frontiers, striking at the imperial

capital, as well as swamping the armed forces in the war zone. During the

summer the Austrian military regularly complained about the Italians' obvious

superiority in the air, enabling them to scatter manifestos en masse. As the

10AK noted in its propaganda report for July,

The Italian

counter-propaganda, which clearly forms one of the most danger-

ous lines

of attack of the Entente propaganda directed at the solid structure of

the Austro-Hungarian armed forces, is as previously very strong even if it

varies on different parts of the front . . . Plane propaganda has become even

more intensive than earlier. Almost every day planes appear and shower not

only the front but also the rear areas with a host of leaflets.

238

All of the army commands viewed this activity with alarm. As one pointed out,

the manifestos were, in addition to the food crisis, an `eminent danger' to troop

morale. They now seemed to be infinitely varied and inventive, skilfully com-

posed by

authors who were well informed and well versed in the mentalities of

the different nationalities; they were following a systematic plan which was

most notable in mirroring that of agitators in the Monarchy itself.

239

Indeed, for the Austrian military, the most striking characteristic was the

degree to which the Italians were using the Austrian press as a major source

The Climax of Italian Psychological Warfare 373

for their arguments. With the enemy simply delighting in reproducing `hot-

blooded speeches'

by MPs like Wichtl, Stra

Â

nsky

Â

or Fe

Â

nyes, Boroevic

Â

observed

with a degree of resignation that the most effective material for enemy propa-

ganda was

supplied by the `miserable internal state of the Monarchy', which was

being reliably broadcast to the enemy by a largely unpatriotic press.

240

Arch-

duke Joseph

(who had succeeded Conrad) concurred, protesting more force-

fully to

Baden that the press was virtually the Entente's servant, uncritically

publishing reports from Reuters and even publicizing the leaflet distributed by

D'Annunzio over Vienna. It was absolutely vital, he warned, to take energetic

steps against this kind of journalism, for all patriotic instruction was pointless

`if the enemy manages to spread with such incredible speed the speeches of a

Stra

Â

nsky

Â

etc'.

241

Yet the AOK could do little to satisfy these complaints from the

front. They could, with their `index', prevent unpatriotic newspapers from

reaching the war zone to a certain extent, but were unable to take more direct

action. They could not unilaterally impose a stricter censorship on the press,

not least because there was no uniformity to press censorship in different parts

of the Empire anyway; nor could they remove parliamentary immunity from

those deputies who made inflammatory statements.

242

The diversity and inde-

pendence of

the press was accurately reflecting the chaotic conditions in the

hinterland. And since there seems to have been no ban on the export of Austro-

Hungarian newspapers to neutral lands like Switzerland, there remained few

obstacles to the Allied propagandists in their task of exploiting and publicizing

the mood of the Habsburg Empire.

8.5 New trials in trench propaganda

The last months of the war also meant an unprecedented level of activity for the

propaganda units, supervised by Italian Intelligence, as they entered what

Cesare Finzi termed `a phase rich in movement and manoeuvre'.

243

The Intelli-

gence offices

especially used their Czech units ever more skilfully to target

Czech troops in the Austrian trenches, with some notoriously successful out-

comes. At

the same time, the propaganda efforts of Italian Intelligence kept

pace with Padua's campaign. Just as Padua's material was penetrating ever

further into the Monarchy, so Czech volunteers were occasionally being called

upon to agitate not just in the front line but across the front, in the Austrian

war zone itself.

There was

a new boldness and danger in this which matched the exploits of

D'Annunzio. If Tullio Marchetti was one who naturally inclined to employing

Slavs in the Tyrol for purposes of espionage or sabotage, some of the volunteers

were keen to take on these new tasks which would prove their worth in the eyes

of Italy while reinforcing their own national pride. Even more, however, many

of the propaganda troops were eager to engage in activities where they would be