Cornwall M. The Undermining of Austria-Hungary: The Battle for Hearts and Minds

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

354 The Undermining of Austria-Hungary

Illustration 8.2 Manifesto 243: Two Czech brothers meet on Val Bella (KA)

propaganda, condemned Seidler for embarking on a German course which

would divide up Bohemia along national lines. Four days later, the leader of

the Czech Club, Frantis

Ï

ek Stane

Ï

k, boasted to the Parliament:

Never was

a people more united and ready for battle, never so certain of

victory as at this moment. The whole Czech nation is united in an unshake-

able determination

no longer to be subject to a foreign yoke under foreign

colours . . . The Czechoslovak state is a fact which is inevitably approaching

realization. On that point, nobody, neither here nor in Budapest, is still in

doubt.

151

The Climax of Italian Psychological Warfare 355

Even the faint stirrings of Slovak politicians from May 1918 were noticed by

Padua just as they were noticed by the military authorities in Hungary. The

manifestos briefly mentioned the important declaration by Vavro S

Ï

roba

Â

rat

Liptovsky

Â

Sva

È

ty Mikula

ÂÏ

s (1 May) calling for self-determination for the Hungar-

ian Slovaks;

as well as Slovak participation at the Prague theatre celebrations

after which the Hungarian authorities had moved against them.

152

Thus the

fate of the Slovaks under a Magyar yoke was clearly, if briefly, portrayed as being

on a par with that of the Czechs in German-dominated Austria.

In keeping

again with the opportunistic character of domestic Czech agita-

tion at

this time, Padua did not have many Stane

Ï

k-type speeches to relay back

across the front. Ojetti was better served by Czech comments from the Allied

side. But the manifestos compensated for this by amply reporting the miserable

economic crisis in Bohemia, contrasting the `famine' in Prague with the food

shortages in Vienna. The German authorities were portrayed as `bloody-thirsty

rogues' who thought nothing of shooting starving women and children in the

streets of Plzen

Ï

;

thus, one leaflet in only a slight flight of fancy concluded that

`Czech blood has already flowed at home and still flows in streams'.

153

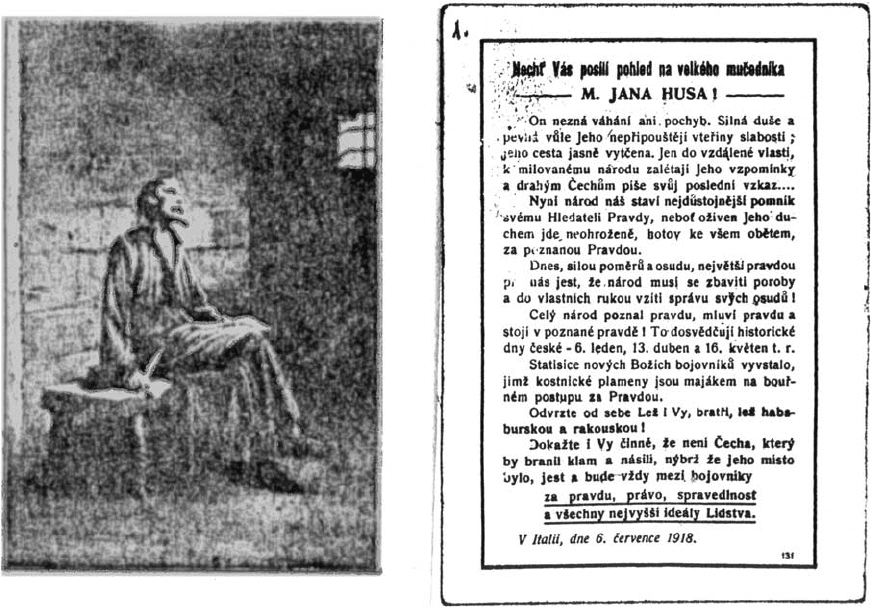

The

main example for Czechs to follow was that of their brothers in Italy, but

Ojetti also resurrected the image of Jan Hus as a worthy predecessor who had

suffered similar torment. Czech soldiers were told to take heart from Hus,

who was pictured in a saintly pose in his cell, and assume their natural role as

`fighters for truth, right, justice and all the greatest ideals of mankind'.

154

Even more than Yugoslav propaganda, Czech propaganda was imbued

with a deeply moralistic and sacrificial streak which drew its strength from

the blood which Czechs were allegedly shedding everywhere for the national

ideal.

Padua illustrated

the comparable suffering endured by Romanians by taking

examples especially from the Romanian kingdom which the Central Powers

had occupied since 1916. The harsh peace treaty which they had imposed in

May 1918 had, according to Padua, transformed Romania into a prison. Under

the puppet government of Alexandru Marghiloman and with 300 000 German

soldiers in control, the country was being bled of its resources of oil and grain.

Civilians, at the mercy of these `barbarous hordes', had even been forced to

remove from public places all pictures of the pro-Entente politician, Take

Ionescu. It was in this deplorable situation that a great Transylvanian poet,

Gheorghe Cosbu, had died in Bucharest.

155

If further proof were needed of the

oppression, it could come from the lips of Take Ionescu himself. Having

obtained permission to go abroad, where some believed he would do less

harm than in Romania, Ionescu arrived in Switzerland on 2 July and gave a

long interview to an Italian newspaper; his description of conditions at home

was reproduced in Padua's weekly Neamul Roma

Ã

nesc

under the caption, `Terrible

German rule in Romania'.

156

Yet as usual, Padua's message was not wholly

356

Illustration 8.3 Manifesto 131: Czechs ought to follow the example of Jan Hus (KA)

The Climax of Italian Psychological Warfare 357

pessimistic. Ionescu, who was to be Romanian foreign minister after the war,

alleged that 99 per cent of Romanians believed that the Entente would win

the war. Other evidence suggested that there was spirited defiance in occupied

Romania. The peasantry were said to be resisting, frequently murdering Ger-

man soldiers;

prominent politicians had protested in parliament against the

charges being brought against the former premier, Ion Bra

Æ

tianu,

for taking

Romania into the war.

157

And even the royal family was setting a good

example. King Ferdinand was keeping his promise that on the attainment of

peace the landed estates would be divided up amongst the peasantry. Queen

Marie, confident of an Entente victory, had, according to an outraged Hungar-

ian newspaper,

made a dramatic tour of the regions ceded to Hungary by the

Peace of Bucharest, assuring local inhabitants that she would `see them again

soon!'

158

Publicizing a similar level of resistance among the Romanians of Hungary was

not so easy. This accurately reflected the stagnation of political life in Transyl-

vania, where

there was strict censorship and little effective Romanian leader-

ship.

159

The manifestos could enumerate Magyar atrocities in Transylvania,

alleging that 15 000 Romanians had been executed during the war, as well as

condemn the treacherous pro-Magyar behaviour of Metropolitan Mangra of

Nagyszeben.

160

They could also give some brief examples of Romanians on trial

in Kolozsva

Â

r for nationalist activity, such as Dr Aristotele Banciu who had

edited a newspaper called `Greater Romania' and now received a jail sentence

of seven years.

161

But when it came to reproducing subversive speeches, akin

to those of a Koros

Ï

ec or Stane

Ï

k,

only one example was forthcoming: that of

Stefan Cicio Pop, speaking in early July in a debate on electoral reform in

the Hungarian Parliament. In response to Count Istva

Â

n Bethlen, who had

remarked that only `living nations' (like the Magyars) should have rights,

Pop had condemned the proposed reform, saying that it would only

further subject the oppressed peoples of Hungary to the ruling classes. He

went on, to cries from one deputy that all Romanians should be executed, to

compare the parliament of 1918 where there were only four Romanians

with that of 1868 which had contained 30 non-Magyar deputies. Padua com-

mented that

the Magyars viewed themselves as the `chosen people of God' and

the Romanians as cattle or cannon-fodder; in revenge, Romanian soldiers

should desert to Italy where there were many brothers waiting to welcome

them.

162

While Magyars and Germans were stifling the rights of Romanians, the Allies

were fighting for their freedom and unity in a greater Romania. Apart from

vague statements to that effect

163

(and it seems questionable whether many

Romanians in the Austrian trenches shared such an ideal), Padua's manifestos

provided somewhat limited evidence. For instance, Take Ionescu had been

received in France by President Poincare

Â

and interviewed by Italian and English

358 The Undermining of Austria-Hungary

newspapers. Albert Thomas, `an enlightened Frenchman who knows and loves

our nation', had usefully observed that Romanians had been omitted from

the Versailles Declaration and advised the Allies to listen to those voices pro-

testing against

the Peace of Bucharest.

164

More striking was the proof which

Padua regularly supplied of Italy's special commitment to the Romanian cause.

Although some notable events such as the founding of an `Action Committee'

under Simeon Mõ

Ã

ndrescu in mid-June received no mention, Ojetti did include

references to festivities in Rome in May, Genoa in June, and Rome again in

August; the latter were organized by Mõ

Ã

ndrescu's group together with Maria

Rygier's `Pro-Romeni' committee and centred on Trajan's column: one historic

symbol of Italian±Romanian fraternity.

165

Something could also be made of the growing presence of Romanian forces in

the Italian war zone. As in Czech propaganda, many of the Romanian leaflets

were signed by `Romanian volunteer officers and soldiers in Italy' who called

upon their compatriots to join them in creating a new legion. Neamul Roma

Ã

nesc

duly informed its readers that in June a small nucleus of Romanian volunteers

had been formed near the front at a ceremony at which a local dignatory

proclaimed the common origin of Italians and Romanians in the `golden age

of Trajan'; the company had then been trained and officially presented with its

colours.

166

Few other details were forthcoming in the following months. Padua

therefore vaguely tried to suggest a movement comparable to the Czech

Legions, observing that `from all sides the Romanians are taking up arms

against the Germans and Hungarians: in Siberia, America and Italy'. In Russia,

there were 30 000 volunteers, in America a similar number had been recruited,

soon to be transported to the French and Italian theatres. Romanian soldiers

needed to be vigilant, for they could be shooting at Romanians and therefore

into the hearts of their children and grandchildren.

167

Padua's Romanian propaganda undoubtedly suffered because we know that

Ojetti diverted Cotrus into writing Hungarian material as well. It was a contrast

to Polish propaganda which was more inventive and abundant, with twice as

many leaflets distributed (overall in the campaign, 14 million as opposed to

seven million Romanian manifestos).

168

This Polish trend continued despite

Zamorski's abrupt departure, an indication that his deputy, Antoni Szuber, was

not only diligent but had learnt much from Zamorski's example. As in the

earliest leaflets, those of the summer months made frequent appeals to Poles

to desert or revolt. They also occasionally contained a distinctive religious

tinge. This was generally absent from other propaganda where at most the

national cause was associated with martyrdom, as in the case of Jan Hus, or in

the Yugoslavs being described as a people `nailed to the cross, awaiting the

moment of deliverance'.

169

Poles in contrast were assured that the Pope sup-

ported Polish

independence, and were urged to pray to God for deliverance

from slavery; with His help they would create a free Poland, raising to heaven

The Climax of Italian Psychological Warfare 359

the glorious hymn, `Glory be to God on High and on earth peace, goodwill

towards men'.

170

Polish material, however, resembled the Yugoslav and Roma-

nian, and

differed from the Czech, in dwelling far more on the `oppressive

regime' of the Central Powers than on new evidence of Allied commitment to

the oppressed nationalities. In the case of the Poles, of course, that commit-

ment had

been confirmed in the Versailles Declaration, and Padua had made

some use of it. But little attention was paid to the activities of the Polish

National Committee since that link was clearly much weaker with Zamorski

absent. The Committee's branch in Rome might well assure Poles in the Aus-

trian trenches

that prisoners in Italy were well-treated,

171

but otherwise, since

there was no substantial Polish volunteer force in Italy, Padua was forced to

report Polish military aid on other fronts to fill up the columns in its weekly

newssheet Polak. In Siberia, Poles could be found organizing themselves in the

Czechoslovak forces, or even as far east as Harbin; and much could be made of

Polish valour in France where General Haller had arrived from the East to

become commander-in-chief of the Polish army.

172

As for evidence of the miserable conditions in Galicia or the occupied regions

of Poland, Padua was supplied by Borgese's bureau with a wealth of information

from the enemy press. Anti-Viennese newspapers such as Illustrowany Kurjer

Codzienny, Kurjer Lwowski (both of which were on the AOK index) and the

socialist Naprzo

Â

d were frequently quoted to illustrate the realities of life for

soldiers' families. For example, in Krako

Â

w, food prices were exorbitant, with a

kilogram of butter now costing 50 crowns, instead of 4

1

¤

2

in 1914, and a kilogram

of beetroot costing 5 crowns instead of half a crown; robbery and profiteering

were rife, and even criminals had to be released from prison because of the lack

of food there.

173

Padua's seventh edition of the weekly Polak alleged that a

cordon had been set up around L'viv to prevent the importing of food, while at

the same time the Austrians and Prussians were requisitioning and exporting

food from Galicia to feed their German populations. Conditions were no better

for Poles living under the heel of imperial Germany. According to a Polish

deputy in the German Reichstag, Polish workers from Silesia, `Poland' and

Lithuania were treated abominably by the German authorities while the latter's

behaviour in the occupied regions, their arrest of the bishop of Vilna for

example, was on a par with the excesses of Tsarism.

174

Padua also mentioned

German persecution of the Jews, but did not feel it necessary to be consistent

on that subject, reporting in other material that Jews were benefiting econom-

ically at

Polish expense in Galicia. More important was to emphasize to Polish

Catholics the simple brutality of the regime for which they were dying, a regime

which viewed the Pole not as a human being but as `a miserable worm, to be

trampled under foot at their pleasure'.

175

With the Central Powers still quarrelling about the status of Poland, any

Polish future under the Germans or Austrians seemed a dismal prospect. Rather

360 The Undermining of Austria-Hungary

than adopting the Austro-Polish solution (linking Polish regions to the Mon-

archy in

a new entity) or creating a free and united Poland (the aim of the

Entente) there were, according to one of Padua's more emotional leaflets,

German schemes afoot to set up a Polish kingdom as had been planned by

Frederick the Great and by `the Russian harlot of German descent, Catherine II'.

It would be a satellite state of the Central Powers where they would possess

unlimited supremacy for 50 years.

176

As for Galicia, the government in Vienna

was allegedly planning to divide it into three parts, one of which would be

incorporated into Austrian Silesia and germanized, while another would fall to

the Ukrainians, a race `even more oppressive than the Russians'[!]. The latter

prospect, heralded through Count Czernin's famous `Bread Peace' with Ukraine

in February 1918, had produced demonstrations in Galicia and ended with the

trial, publicized by Padua from scanty information, of Polish legionaries at

Ma

Â

ramarossziget.

177

It had also turned most Polish deputies in the Reichsrat

against the Seidler government. Having reported the Polish Club's resolve to

oppose Seidler when the Reichsrat reopened in July, and observing correctly

that this would lead to Seidler's resignation (since he relied on them for his

majority in the chamber), Ojetti was then able to quote at length the speeches

of Polish deputies, condemning Austrian policy and Seidler in particular (`a

stubborn foe of the Poles').

178

The speeches on 17 July by Tertil, Daszyn

Â

ski

and

GøaÎ bin

Â

ski

sharply criticized Seidler's `German course' and especially his sup-

posed renunciation

of the Austro-Polish solution through his secret deal with

Ukraine. Ignacy Daszyn

Â

ski

went on to advise Ruthene deputies in the Reichsrat

to fight for their own national rights and not to put their trust in Vienna, for `a

bankrupt can promise absolutely nothing and this government is bankrupt'.

179

It was a message entirely in tune with that of the Allied propagandists. They

could bluntly answer their own question as to whether Polish soldiers should

continue to defend Austria: `the best representatives of the Polish nation say,

NO!'

180

The richness of propaganda material in Polish, something noted by the

Austrian 10AK in August, stood in striking contrast to the meagre number of

manifestos in the Ukrainian language (only 25 types produced).

181

This was

largely due to Polish control over the material.

182

In particular, since the Polish

e

Â

migre

Â

s aimed to include all of Galicia in an independent Poland, the Ruthenes

of eastern Galicia could never be promised their own independence. Zamorski,

however, had been keen from the start to send some appeals to Ruthene

soldiers. In mid-May he had written to Antoni Szuber, who was working in

Polish prison-camps near Naples, asking if he knew of a Polish officer from

eastern Galicia who could write manifestos `in a manner tuned to the Ruthene

psychology'. Since Szuber signalled that he himself was competent, he was

called to the Padua Commission in early June. The Versailles Declaration had

now strengthened the Polish case. Zamorski and Szuber were therefore able to

The Climax of Italian Psychological Warfare 361

persuade Ojetti that Ruthenes should not be offered independence (which

the Allies were silent about anyway) but only general slogans about Austrian

oppression.

183

Szuber's Ruthene material deliberately tried to avoid the

`national issue', or what he termed `blowing at the embers' of the Polish±

Ruthene question in Galicia. Yet as we have seen, he was not wholly averse to

exploiting Ruthene loyalty to Vienna in order to reinforce his Polish propa-

ganda.

When Zamorski

had left Padua, Szuber naturally concentrated on his Polish

leaflets. And according to what had been agreed, Ukrainian propaganda was

always limited in scope to reminders about German and Austrian brutality in

the East. Thus, while the destitute townspeople were `living on grass and the

roots of trees . . . perishing by the thousand from hunger', police in L'viv on

8 June had fired on starving women and children.

184

In Ukraine meanwhile,

the Central Powers, having invaded ostensibly to chase out the Russians, had

proceeded to behave `like a tapeworm eating an organism from within', quite

prepared to `let the Ukrainians perish so that the accursed Germans in Vienna

and Berlin' could `scoff sausage and cabbage with a glass of beer!'

185

Ruthene

soldiers were asked to consider whether their service in the Austrian trenches

was not equivalent to behaving like `Cain' against their brothers in distant

Ukraine. For there, rather than obeying passively, `more than 75 000 well-

armed villagers under the leadership of valiant commanders are moving on

golden-roofed Kiev', rebelling against the barbarism of German rule and declar-

ing their

own independence.

186

Padua's material in Italian was on an even smaller scale, consisting only of

some general manifestos issued in other languages, and reflecting perhaps

Italy's awareness that there were few Italian-Austrian soldiers on the south-

western front.

187

Instead, the Italian Intelligence offices continued to publish,

notably in the wake of the June offensive, their own emotional appeals to

civilians in Venetia. These warned them about having too much truck with

the occupying forces, since `these snakes can poison with breath and word the

air which you breathe', polluting the purity of one's patriotism. The civilians

were assured, with personal messages from relatives in Italy, that the day of

resurrection was approaching: `the clearest light of tomorrow will be for those

who have kept hope in the darkness of foreign domination'.

188

In response,

many Venetian civilians appear to have dutifully collected and concealed the

propaganda leaflets, either out of simple curiosity, or deliberately, like the

mayor of one town who in late July was found to have 200 manifestos stored

in his house.

189

They also generally followed Italy's advice. Most Austrian

official reports from Venetia, from June until November, observed that the

civilians were maintaining a passive and reserved attitude towards the occupy-

ing regime,

confident that Italy would soon launch a new offensive to bring

them liberty and sustenance.

190

362 The Undermining of Austria-Hungary

8.4 Padua's summer campaign: the Magyars and

German±Austrians

While it was a core aim of Padua's propaganda to appeal to the traditional

`oppressed nationalities' (the Slav and Latin races), Ojetti also increasingly

targeted those of Hungarian or German±Austrian nationality as well. They too

could be portrayed as oppressed in their own way, both nationally and polit-

ically. Magyar

soldiers in particular were viewed as a major target during the

summer. Before the June offensive the Italian military had regarded Magyars as

too reliable to merit much attention from their propaganda; and Padua, lacking

a suitable translator, had duly published only two texts in Hungarian (totalling

315 000 copies).

191

However, a change of attitude occurred after the offensive by which time

Cotrus had joined the Commission. Apart from the outcry from Budapest by

radical Hungarian politicians and newspapers at the `needless slaughter' on the

Piave, there was now strong evidence from the statements of Magyar deserters

and prisoners that many of them too shared misgivings about the war and the

Germans, and might well be receptive to Allied propaganda.

192

On 14 July,

Granville Baker reported to Northcliffe that, although as yet Padua's Magyar

propaganda had had no `decisive effect', he had noticed when visiting Magyar

prisoners that they were much more willing to talk; he concluded that `propa-

ganda may

be pushed on now with more hope of success'.

193

Ojetti clearly

agreed, for from mid-June to mid-September the amount of material produced

in Hungarian, 62 new texts totalling six million copies, was only marginally less

than the amount directed at Yugoslav soldiers. Ojetti, when writing his final

propaganda report at the end of the war, would explain why Magyars had been

the target for over nine million manifestos:

Because these

people began to understand that they were now tied to a

corpse and they sensed, every day more clearly, that their salvation

depended solely on their total separation from the alliance with Germany

and the union with Austria, and then on their economic and social revival

on sincerely democratic bases in opposition to the feudal oligarchy of noble

or ennobled latifundists.

194

These at least were the two major arguments employed in Padua's Magyar

material by Cotrus.

The first

argument, that of appealing to Magyar nationalism, continued to be

the principal theme of the leaflets in the tradition begun by Italian Intelligence

officers in the spring. It was displayed perhaps most ingeniously in manifesto

109, which referred back to the Waffenbund or military alliance cemented

between Germany and Austria-Hungary in May 1918; despite containing a

The Climax of Italian Psychological Warfare 363

number of errors, it continued to be distributed well into the summer. The

leaflet was edged in black and inscribed with the words:

Here lies

Hungary

and her

children

Freedom and

Independence

born in

1848,

died after fighting for 4 years

on the Italian front

for Germany, Austria and Turkey.

Burial will take place at Spa in the

`Waffenbund' cemetery at Germany's expense.

It was

dated at Spa (the German military headquarters), and signed by `Wilhelm

II Hohenzollern, Europe's chief funeral director' and `Karl III Habsburg, private

secretary'.

195

By July 1918 some Austrian commanders were noting this new tendency of

enemy propaganda to launch appeals at Hungarian troops, one observing that

they would have to be energetically countered if found to have links to the

Hungarian hinterland or press.

196

Such connections were soon quite apparent,

for radical Budapest newspapers were Padua's best source of information, as

usual reinforcing the truth of what was being propagated. Organs such as Az Est

and Vila

Â

g could regularly be used to condemn the German alliance, that it was

creating a Mitteleuropa where Hindenburg would be master: `your children and

grandchildren would not be learning about Ra

Â

ko

Â

czi or Peto

Â

Â

fi

or Kossuth but

about the great deeds of him and Kaiser Wilhelm!'

197

Such concern could now

be echoed in detailed speeches reproduced from the Hungarian Parliament.

There on 21 June, in a particularly lively session, a vociferous opposition

deputy, Na

Â

ndor Urma

Â

nczy, had attacked the Minister of Defence for permitting

discrimination against Magyars in the army, and demanded a government bill

to establish an independent Hungarian army. A like-minded colleague, La

Â

szlo

Â

Fe

Â

nyes, proceeded to denounce the German alliance for its economic and

military exploitation of Hungary.

198

The same sources were repeatedly quoted by Padua to illustrate the enormous

and futile sacrifices made by Magyars for German interests during the Piave

offensive. There had been a storm of protest in Budapest at the conduct of the

war. According to vivid reports from Az Est, most of the 10 000 lost on the

Piave had been Magyars who had died like martyrs on foreign soil.

199

It was

a point reiterated by Fe

Â

nyes in several blistering attacks on the Hungarian

government; and by Urma

Â

nczy who, on 24 July, in a speech which the

AOK tried to prevent from reaching the war zone, heaped blame on the