Cornwall M. The Undermining of Austria-Hungary: The Battle for Hearts and Minds

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

344 The Undermining of Austria-Hungary

of the German people', and that Habsburg soldiers ought to break their own

chains immediately if they were not to suffer the same dismal fate.

105

Certainly

(and here Ojetti's use of the `German threat' was turned on its head) the

Austrians could no longer expect any help from Germany on the Italian

Front. Rather, like `a drowning man grasping at a straw to keep above water',

Germany had demanded that its ally send troops to the West.

106

The reality in

fact was that the AOK had only reluctantly agreed in late June to dispatch two

infantry divisions (the lst and 35th) to the Western Front.

107

But for Padua, the

issue of Austria's full subservience to Germany was always a major theme to be

set out in the starkest colours. Thus: `The faithful servant of Germany, Emperor

Karl, has already sent some of his starving divisions to the French Front to

rescue Germany and pan-Germanism'; other divisions would be following to be

treated by Hindenburg as cannon-fodder, `driven to the butcher's slab by the

manic madness of the German and Austrian Emperors'.

108

Nor was there any prospect of a change in fortune for the Central Powers.

A second supra-national theme in Allied propaganda during the summer was

the vastness of American resources. Already by 1 July, according to a much-

publicized correspondence between President Wilson and his Secretary of War,

there were a million Americans in France; with 10 000 new soldiers reaching

Europe every day, the number would total two-and-a-half million by Christmas

and four million by spring 1919.

109

In contrast to the exhausted troops of the

Central Powers, the American soldiers were `young and robust men of 20±25

years of age. They fight like lions and are certainly the best soldiers in Eur-

ope.'

110

They were only the tip of the iceberg of what the United States could

and would contribute to the Allied cause of freedom and justice, disproving the

earlier claims of Austrian propaganda that the war would be won before the

Americans could make an impact. In manifesto 269 entitled `What all America

contributes to annihilate the militarism of Germany and Austria-Hungary' (the

information for which appears to have been telegraphed to Padua by Crewe

House), enemy soldiers were reminded that America was replacing for the En-

tente what

had been lost through Russia's withdrawal from the war. The speech

of nine Congressmen visiting London was quoted to show America's resolve to

fight until militarism was crushed and its capability of doing so: namely, its

stock of 20 million troops, its endless food supplies, its 25 000 planes, its daily

production of 720 000 shells.

111

Well might the Arbeiter-Zeitung (a favourite

source for Padua) comment that America's entry into the war dissolved the

Central Powers' hope of a victory through arms, for it now appeared that the

reserves of the whole world were at the Allies' disposal. Even distant Siam was

doing its bit in the crusade against Prussian militarism by supplying 500 avi-

ators to

the European battlefields.

112

Such a united front could easily be contrasted with the Monarchy's blatant

inability to continue the war for much longer. Borgese's bureau in Berne did

The Climax of Italian Psychological Warfare 345

not have to search the Austrian press too thoroughly to supply Padua with good

examples of the appalling food crisis in the empire. At the same time that

American ships were bringing daily supplies to the Allies, the mayor of Vienna

was publicly accusing the Germans of not fulfilling their promises of grain;

there were hunger riots in Galicia; civilians were eating grass in Bosnia; and,

allegedly, even the Viennese Reichsrat had to be adjourned in late July because

the parliamentary buffet had run out of food!

113

Nor was there the remotest

possibility that the authorities would find grain supplies in Ukraine as they

had bragged earlier. As Padua regularly reminded its readership, events in

the East were chaotic and now running counter to the Monarchy's interests.

The Russian people was rising up against the Bolshevik regime and its hated

German supporters; German representatives such as Mirbach and Eichhorn

had been assassinated;

114

and the shock of Allied military success in Russia

had allegedly been so great as to cause Kaiser Wilhelm to fall ill. Thus Lenin's

regime, portrayed by Ojetti as `the tyranny of a few Jewish profiteers', was

rapidly nearing its end: instead of grain supplies, the Central Powers were

allegedly finding a new front being set up against them in the East.

115

Simultaneously with this theme of the inevitable defeat of Austria-Hungary,

Padua broadcast to the different nationalities a message of hope: that the Allies

were fighting for a just peace and liberty for all peoples. This message could be

individually packaged for each nationality, and it carried increasing weight in

these months, firstly because of the West's public commitment to the nationality

principle, and secondly because of the extent to which radical nationalism was

taking firm root in the Monarchy itself. This is not to deny that Padua's argu-

ments were

stronger for some nationalities than others (for the Czechs more than

the Romanians, for the Poles far more than the Ruthenes), reflecting in itself the

respective progress made by each national movement at home and abroad. Even

so, Ojetti still managed to focus his data quite effectively in order to match the

prevailing range of ethnic mentalities. It was a fact which was duly acknowledged

by the Habsburg authorities, making them feel all the more beleaguered.

With regard

to propaganda directed specifically at `Yugoslav' soldiers or

civilians, the Commission produced from mid-June to mid-September 54 new

manifestos (about five million copies) and 12 editions of the weekly newssheet

Jugoslavija (1 400 000 copies). This was about 20 per cent of the total production

in this period.

116

Most of it, signed by the `Yugoslav Committee' and contain-

ing far

fewer spelling and typographical errors than before, was in the Croat

language, possibly again an indication that Padua wanted to stress a Yugoslav

uniformity, or perhaps simply a sign that typesetting in the Cyrillic script was

more difficult. There was also now an increasing amount of material in the

Slovene language, including Slovene passages in the newssheet, due to the

active participation of Stojan Lasic

Â

whom Kujundz

Ï

ic

Â

described as `loquacious

but very industrious and useful'.

117

346 The Undermining of Austria-Hungary

Much of the Yugoslav propaganda proclaimed the vague ideal (with no

mention of the Corfu Declaration or territorial issues) of a free, united and

independent state of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. According to one special

newssheet, manifesto 203, published to commemorate the outbreak of war

between Serbia and Austria, `Now we are split up, separated like fingers on a

hand, we must concentrate them into one so that from weak digits there

becomes a strong fist.' This, the pamphlet maintained, should not be feared

as a `Bolshevik dream', for the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes were one nation of

12 million people who desired a Yugoslav state and had the firm backing of

the Allied Powers.

118

In view of the confusion over the Yugoslav issue in Allied

lands, it was naturally a lot easier for Padua to make these vague pronounce-

ments of

Allied commitment than to give concrete evidence of that pledge. The

leaflets asserted that an independent Yugoslav state was one of the Entente's

conditions for peace, even though the only real proof of this was given in

Robert Lansing's statement of 28 June, and in a declaration by the American

Senator Henry Cabot Lodge on 24 August.

119

Even so, as we have noted, Padua

also did not make the most of the `evidence' that was available. Its output

appears to have contained no reference to Pichon's statement of 29 June, nor

to Balfour's Mansion House speech which Steed had expected to be `excellent

material for propaganda'.

However, in

the early summer in particular, the theme of warm Italian±

Yugoslav cooperation continued to be a regular motif in the manifestos. During

the Piave offensive, `Trumbic

Â

', while urging his compatriots to revolt, assured

them that `relations between us and the Italians are first-rate and we have also

told each other that in the future we will live as the best of neighbours and

friends'.

120

It was a message which seemed to be confirmed by accounts of his

official meeting with Orlando, or by the celebrations in Rome on 28 June to

mark the anniversary of the battle of Kosovo. At the latter event Trumbic

Â

had

spoken of the Allies' solidarity and of his enthusiastic reception at the prison

camp of Nocera Umbra the previous day, while Andrea Torre had read out a

telegram from Orlando, reminding the audience that in spite of two defeats on

Kosovo field the Serbian people had never been conquered; like Italy, they too

would rise again to take part in a brilliant future.

121

In similar vein, though

without the Italian link, the `Yugoslav Committee' spoke directly to enemy

soldiers of Serb nationality in one of the few leaflets printed in Cyrillic script:

Kosovo became

the symbol of our national Golgotha, but was at the same

time a horribly expensive lesson which today especially we must make use

of . . . Now is the time when, learning by our experience, we must avoid a

new Kosovo which would bury for ever our freedom and unity. We will avoid

it if, with that same sacrifice with which the knights of old fought `for the

holy cross and golden freedom', we fight for our unity and freedom.

122

The Climax of Italian Psychological Warfare 347

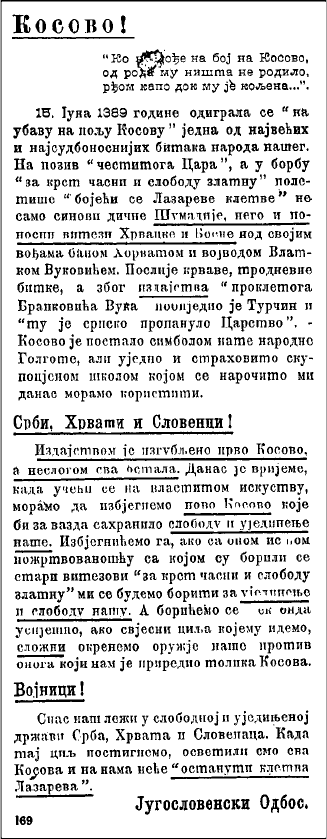

Illustration 8.1 Manifesto 169: Serbs should reflect on the lessons of Kosovo (KA)

That Italy was still committed to this same ideal, and was helping to avenge

Kosovo and banish the `curse of Prince Lazar' (killed at the fateful battle in

1389), might be deduced also from the way in which the Italians were treating

Yugoslav prisoners. Manifestos composed in the early summer continued to

mention the `extraordinarily kind' treatment of prisoners, of how they were

348 The Undermining of Austria-Hungary

united with their compatriots and were cared for by delegates from the Yugo-

slav Committee:

On the

14th [ July] two delegates of the Yugoslav Committee visited our

prisoners. They could not recognize them as they had made such a good

recovery. One Bosnian declared that, after reading our newspaper he deserted

because he saw where the truth lay. Now he is not sorry, as not only has he

saved himself but he does not have to fight anymore for the Krauts and

Magyars, the greatest murderers of our people.

123

Not surprisingly, in view of Italian sensitivity about Yugoslav prisoners, such

visits could not be described in later leaflets, nor could Padua dwell as in its

Czech material on the presence of a strong volunteer force at the front. There

could be hints that a Yugoslav legion was in the making, that prisoners in Italy

could volunteer to fight against Austria (and were not compelled to do so as the

Austrians disgracefully suggested). But generally Ojetti had to make the most of

references to Yugoslav forces in Russia or America. The realities of the situation

in Italy therefore limited Padua's arguments on this subject, as also on the

broader theme of Italo-Yugoslav cooperation to which there were few refer-

ences in

the propaganda material composed in August.

124

While vaguely supporting a free and united Yugoslav state, Padua continued

to emphasize as its antithesis the oppression of the South Slavs which was a

major aim of the German and Magyar races of the Monarchy. This contrast was

perhaps most vividly illustrated by manifesto 101, an open letter from Trumbic

Â

to FM Boroevic

Â

dated 23 June. It was actually written by Jambris

Ï

ak by mid-June

and, after a thorough vetting by Ojetti, was distributed widely over the front

and southern Slav regions.

125

According to Delme

Â

-Radcliffe, Padua did not

expect the leaflet to influence Boroevic

Â

himself, but hoped that it would

`produce a considerable sensation among the population'.

126

In the leaflet

Trumbic

Â

begged to say a few words to the Field Marshal at `this critical moment

for the development of all mankind'. At a time when the Yugoslav people

wished to be master of its own house and the Allies, especially Italy through

the historic resolutions of the Rome Congress, had shown their commitment to

this ideal, why was Boroevic

Â

, instead of acting as a liberator for the Yugoslavs,

leading the flower of the nation to destruction? Did he not realize that he was

fighting for `an obsolete anachronistic principle', for Germany, against whom

the whole world had arisen since `the very essence of German authority and

culture is a misfortune for humanity'?:

A culture

which in every way systematically brings immorality to all non-

German peoples, a culture which develops the lowest instincts in the non-

German masses, isolates them and causes dissension amongst them, and

The Climax of Italian Psychological Warfare 349

then with its brutal military hand subjects everything to its service ± there!

that is the present German culture, that is the picture of Mittel-Europa.

Knowledge, science, technology, everything had and has to serve the Ger-

man plan

to rule the world. One should remember the German ways and

methods in Russia and among the oppressed peoples of Austria-Hungary.

The spread of alcoholism, the spread of pornographic literature, corruption,

the destruction of family morality amongst the nations, those are the

methods and fruits of German culture.

Those were

the aims which Boroevic

Â

was serving, falling into the same error as

Ban Jelac

Ï

ic

Â

, the Croatian hero of 1848, who had served Vienna only to have a

brutal absolutism imposed on his people in the 1850s. History, warned `Trum-

bic

Â

',

was merciless in its judgement: Boroevic

Â

had started on a course which

could result in his replacing Vuk Brankovic

Â

(the traitor of Kosovo) in future

Yugoslav ballads.

This diatribe

against all things German, which at the same time tried to

appeal to a hazy Yugoslav history encompassing both Croat and Serb traditions,

drew the particular attention of the Austrian authorities in view of its direct

attack on Boroevic

Â

. Max Ronge thought it worthy of mention in his memoirs,

while the FAst was quick to condemn Trumbic

Â

in one of its circulars, praising

Boroevic

Â

as `the better son of his people' for knowing that the only real enemy

of the South Slavs was Italian imperialism.

127

For Padua, it was only the start of

a mass of leaflets which sought to display the reality of German and Magyar

oppression in the Monarchy, based on a far wider range of information than

previously possible. The Empire was described as being, since Karl's `Canossa' to

Spa in May 1918, another version of Turkey, completely subordinate to Ger-

many. In

military terms this did not only mean that Habsburg troops on the

Italian Front were dying at the German Kaiser's command, but was given a

more sinister twist:

According to

reliable news, German troops are already to be found in the

Monarchy and are disguised in Austrian uniform. Others are concentrated

on the border and they expect at any moment the order to march in. In

Budapest, where German troops arrived with the excuse of creating order

and peace, the people are unusually excited. Bloody conflicts are the order of

the day, and at night attacks on German patrols are so frequent that the

government has adopted the strictest measures to prevent them. So the

Monarchy suffocates already with a fatal death-rattle.

128

This story was sheer fabrication, but was let through by Ojetti as a simple

exaggeration of underlying realities. It was matched by manifestos alleging

that on 30 April hundreds of Magyar troops had invaded Zagreb, brutally

350 The Undermining of Austria-Hungary

attacking the homes of two Croat MPs and finally occupying the Croatian

assembly itself. As one newssheet concluded: `Drunken Magyar hordes are

smashing and violating all that you hold sacred. Tell each other secretly what

you need to do.'

129

More reliably, Borgese's bureau in Switzerland was able to extract from the

Austrian press the news of two damning declarations which spoke volumes

about the real mentality of some German leaders in Austria. On 16 July, the

Viennese Reichsrat had reconvened for the first time since March. The Prime

Minister, Ernst von Seidler, in a speech which one deputy warned would be of

great value to the Entente's propaganda offensive,

130

had bowed to German-

Austrian pressure and recognized his government's `German course', that one

could not rule against the interests of the Germans in Austria as they formed

the backbone of the Monarchy.

131

In seizing upon Seidler's open partiality for

the Germans, Padua proceeded to link his `internal offensive' in the Reichsrat

against the Slav±Latin majority of Austria with the renewed German offensive

on the Western Front against the Allies. Convinced that Germany's attack

would be successful, Seidler had prematurely dropped his Austrian mask to

reveal his pan-German face. Then, Padua maintained, when Germany was

rebuffed in the West, Seidler had been forced to resign as Prime Minister by a

desperate Austrian elite who were now on the defensive themselves.

132

If further proof were needed that Austrian policy was serving pan-German-

ism, Padua could recount appeals by the Germans of Vienna, demanding a

`German course' against all Czech and Yugoslav aspirations, and particularly

the striking declaration of a notorious German radical deputy, Friedrich

Wichtl.

133

Wichtl's speech, in Styria on 12 July, was published in the Maribor

daily Straz

Ï

a, was unashamedly racist, and for that reason came in for some

criticism even from military quarters.

134

Answering his own question as to what

should be done with the Slavs, he said: `We must decimate their number and

break up their unity, otherwise they really will become extraordinarily danger-

ous for

the German race.' Asserting that war was the best means to achieve this

goal, he gave figures to show how the Germans had successfully exterminated 20

million Slavs in the previous four years, predicting that with another two years of

war the Czechs could be completely destroyed. However, he warned, the Yugo-

slavs as

a compact mass, not surrounded by Germans, were more threatening

than the Czechs and should at all costs be prevented from creating Yugoslavia:

We must

seek to decimate the Yugoslav people. We have the means for

achieving this goal: German schools, war, lack of food or, in other words,

starvation. The alliance with Germany must correspond to German desires.

The alliance must be a common German house in which we will speak only

German, think only German and wage war only in the German way. Thus

Germany and Austria will form only one state: a Greater Germany.

135

The Climax of Italian Psychological Warfare 351

It was not difficult for Padua to portray Wichtl's dream as nearing reality. Apart

from the alleged military and political subordination of the Monarchy to

Germany, the same message could be stressed in economic terms. To give one

example, the governor of Trieste seemed to be following `the perfidious recipe

of the notorious Slav-devouring [slavoz

Ï

dera]' Wichtl when he ordered requisi-

tioning among

the already famished population of Istria and the Croatian

islands.

136

In these circumstances Padua's manifestos stressed that it was not enough for

a good Yugoslav soldier simply to declare `in merry company with a glass of

wine' that he hated the Kraut and Magyar. Rather, now was the time to follow

the example of legendary `Yugoslav' heroes like Zrinjski or Matija Gubec, to

turn all weapons against the tyrants, against `that monster which is called

Austria-Hungary'.

137

Those Yugoslav troops who still hesitated to act because

of loyalty to the Habsburgs were reminded that Karl as King of Croatia had

himself trampled on his oath to the Croats and Serbs by permitting Magyar

oppression in Croatia. `Credible' rumours were also now circulating in the

Monarchy, accusing the imperial family, and Empress Zita in particular, of

treachery and espionage to the benefit of the enemy: crimes in other words,

for which thousands of Yugoslavs had been executed during the war. Reprodu-

cing this

gossip from the Austrian press was the nearest that Padua ever got to

openly attacking the imperial couple apart from briefly describing Karl as a liar

(because of the Sixtus Affair) or as the servant of Kaiser Wilhelm. It was a sign

that, in contrast to the latter who could be vilified at every opportunity, the

Austrian Emperor was rarely viewed as a worthy target.

138

For Yugoslav soldiers, the path which they should follow had been mapped

out by their heroic historic predecessors. But they could also emulate their

contemporary leaders in the hinterland, many of whom by the summer

months were moving into a new phase of grass-roots mobilization on behalf

of South Slav unity and opposition to the Habsburgs. To illustrate this radical

shift, Ojetti again had far more material to hand than previously. He was able

for example to reproduce `ten rules for the true Croat, Serb and Slovene' which

seem to have first appeared in mid-July in Volja Naroda, a radical new paper

being published in Varaz

Ï

din; the Zagreb military authorities had tried to pre-

vent it

reaching troops in the war zone.

139

But Padua was also able, mainly

from information secured via Berne, to give hints and sometimes more specific

information about the real progress of Yugoslav agitation in the Monarchy. In

keeping with the actual state of affairs,

140

little could be said about the political

movement in Croatia where the Serb±Croat Coalition continued to maintain

an opportunistic stance until October 1918. Only the Coalition's opponents

could be quoted as having demanded in the Sabor (27 June) that the Yugoslav

question should be settled on the basis of national self-determination as recog-

nized by

all free and democratic states of the world.

141

352 The Undermining of Austria-Hungary

However, with regard to the more radical movement in Slovene regions,

where plans were afoot in the early summer to establish in Ljubljana a National

Council which would eventually be a branch of a central Yugoslav Council in

Zagreb, useful details of the mounting agitation filtered through to the Allied

propagandists. They could report important resolutions made by Slovene social-

ists about

self-determination and Yugoslav unity, as well as news from the

Swiss Neue Zu

È

richer

Zeitung according to which on 1 June a National Council

of all Slovene political parties had been founded in Ljubljana. This was actually

inaccurate, since on 1 June the Slovene leaders had only discussed future

organization of such a council (and socialists had declined to join it).

142

But

when it came to the actual event, the so-called Slav Days of 16±18 August at

which a Slovene National Council was created in Ljubljana, Padua was fully

alert to its significance and proclaimed: `Greetings to you, white Ljubljana,

capital of Slovenia, northern seat of Yugoslavia! . . . An important chapter in

the history of your people is written today in your house!'

Subsequent manifestos

stressed that the Slav Days were vital not only as proof

of the awakened consciousness of all Yugoslavs, for Slovene, Croat and Serb

leaders had all participated; but also, as Anton Koros

Ï

ec himself intended, as a

further manifestation of solidarity between the Yugoslav, Czech and Polish

nations. For just like the celebrations in Prague in May 1918, so in Ljubljana

in August, distinguished Czech and Polish representatives joined with Yugoslav

politicians in calling for freedom and national unification.

143

These meetings

had been convened on a date which coincided with the Emperor's birthday and

had taken place despite police prohibition; there had been little regard for the

authorities' demand for strict censorship in press coverage of the events.

144

Padua was easily able to acquire the main details and hammer them home in

its manifestos. Indeed, the Slav Days aptly reflected the crumbling state

of Habsburg authority in the summer of 1918, something which the Padua

Commission summed up in one of its most vivid passages in the Slovene

language:

Germany and

Austria lit the conflagration, but they did not think that there

would accumulate in Austria in the course of time so much fuel to be able to

inflame the whole house if it caught fire. The oppressed Austrian peoples are

that fuel and that enormous mass has now been set alight, and all the

German and Magyar firemen are not able to extinguish the conflagration

engulfing the old Austrian house. `Fire! Fire!' cry the frightened firemen.

They mobilize all the Austrian hose-pipes of the old and new systems, but

the blaze spreads ever further. In vain are all your efforts, German and

Magyar firemen! You should have thought about the possibility of fire

before. Now it is too late! Your house is burning to the ground, and we are

building a new one according to our plan and without you.

145

The Climax of Italian Psychological Warfare 353

As with the Yugoslav material, propaganda in the Czech, Romanian and

Polish languages in the summer emphasized a simple polarization of the ideo-

logical struggle

in Europe. On the one hand was the imminent victory of the

national struggle for freedom, the struggle being successfully waged both by the

West and in the Monarchy; on the other hand, the tyranny and misery which

any German victory would entail. Czechoslovak propaganda, none of which

was in Slovak, could of course give far more proof than the Yugoslav about the

vitality of the Czechoslovak cause in Allied countries. It consistently played on

the existence of the Czech Legions. In Russia, where Czech troops were fighting

against Bolshevism along the Trans-Siberian railway, they could be praised as

making a major contribution to both the Allied cause and the cause of Czech

recognition.

146

Nearer home, Padua's manifestos were often signed by `soldiers

of the Czechoslovak army in Italy'; they dwelt as usual on their excellent

treatment, but particularly now on their heroism during the June offensive

when Czechs and Italians had spilt blood for a common ideal.

147

A constant

refrain, that Czechs should not fight against their own countrymen, was most

poignantly transmitted in manifesto 243, `Brothers! Brothers!' This described

an actual incident which had occurred on Monte di Val Bella in June, when two

brothers from the opposing trenches had encountered one another. The leaflet

colourfully illustrated their embrace, while reminding Czechs that they all had

a fraternal bonding from their Hussite and Sokol heritage, were sons of the

same Bohemia, and were viewed by Italy as sons of a fraternal nation.

148

If Italy's commitment to the Czech cause was implicit in the presence of the

Legion, and more openly espoused by Orlando after the Piave victory, Czech

propaganda could further offset any perceived weakness of the Versailles De-

claration through

the British, French and American statements which had

flowed out in the early summer.

149

The most crucial, as we have seen, was

Balfour's declaration of 9 August. This British recognition of the Czechoslovaks

was given the widest publicity by Padua, more so than any other Allied state-

ment in

1918, in almost all languages of the Monarchy. It was trumpeted not

only as signifying de facto independence for a Czechoslovak state, but also, as

even the German press warned, as tantamount to Delenda Austria: `the decay

and end of the hitherto existing Habsburg Empire'.

150

Quite correctly, the

Austrian authorities could be alarmed, for the Czech leaders at home and

abroad now felt fully justified in proclaiming their cause as an `international'

issue which could only be solved at the peace conference.

As in

the southern Slav regions, the Czech movement at home also began to

crystallize in the early summer. Padua duly reported that on 13 July a National

Council had been created in Prague which called for self-determination for the

Czechoslovak nation. This could be set alongside newly strident speeches from

the Czech Club in the Reichsrat. On the 22nd, Adolf Stra

Â

nsky

Â

, in a speech

which one army command rightly suspected would be exploited by enemy