Bongard Frederic , Darryl Sue. Diagnosis and Treatment Critical Care

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

GASTROINTESTINAL BLEEDING

707

decrease in incidence is probably due to wide use of stress-

ulceration prophylaxis in ICU patients.

B. Portal Hypertension—Varices are a hallmark of portal

hypertension, most commonly caused by liver cirrhosis. The

lifelong risk of variceal bleeding is about 50% in cirrhotic

patients. For patients with variceal bleeding, prognosis is

poor. Without treatment, the risk of rebleeding is 70%. Each

episode of variceal bleeding carries 30% mortality rate.

The size, location, and endoscopic appearance of varices

and the Child-Pugh score are the most important independent

predictors of variceal bleeding. Varices that are larger than 6

mm or that occupy more than a third of the lumen portend

the highest risk of bleeding. Esophageal varices are responsible

for most cases of variceal bleedings, whereas gastric varices

account for fewer than 30%. Usually, gastric varices are found

in combination with esophageal varices, but isolated gastric

varices should prompt evaluation for splenic vein thrombosis.

If isolated splenic vein thrombosis is present, splenectomy is

the therapy of choice. Gastric varices, and in particular, iso-

lated fundic varices, tend to produce severe and difficult-to-

control bleeding. Endoscopic appearance of varices is also a

bleeding risk predictor. Red streaks or “cherry” or cystic spots

(“blood blisters”) are high bleeding risk endoscopic stigmata.

Development of varices parallels the progression of liver

disease. Thus patients with higher Child-Pugh scores are more

likely to have varices and are at higher risk for variceal bleed-

ing. As an example of these factors put together, a Child’s C

cirrhotic patient with large varices and endoscopic red streaks

has a 76% yearly risk of variceal bleeding, whereas the risk

drops to 10% for a Child’s A patient without other risk factors.

UGI Bleeding Diagnosis and Treatment

Over the past decade, significant advances have been made in

the diagnosis and treatment of UGI bleeding. Endoscopy has

evolved from a merely diagnostic technique into a com-

monly used therapeutic modality. Endoscopic therapy

decreases mortality and the need for surgery and reduces

rebleeding rates, length of hospital stay, and transfusion

requirements. Endoscopy also plays an important role in

patient risk stratification, allowing for significant cost savings.

The armamentarium of available diagnostic techniques has

further expanded with the invention of capsule endoscopy. A

small camera/capsule is swallowed by the patient and trans-

mits 360-degree pictures throughout the UGI tract. In par-

ticular, capsule endoscopy significantly improves localization

of small bowel bleeding lesions. Another new endoscopic

technique is double-balloon enteroscopy, which allows for

endoscopic examination of the entire small bowel. It is still

under development and has limited availability.

A combination of endoscopic and pharmacologic therapies

is successful in great majority of UGI bleeding patients.

Currently, 95% of UGI bleeding patients respond to combined

endoscopic and pharmacologic therapy. Therefore, surgery and

interventional radiology techniques are reserved for patients

who fail endoscopic management. Below we focus on endo-

scopic and pharmacologic approaches to the two main types of

UGI bleeding: peptic ulcer and variceal bleeding.

Peptic Ulcer Disease

A. Endoscopic Diagnosis and Treatment of Peptic Ulcer

Bleeding—Endoscopic findings determine the need for endo-

scopic therapy and guide further decisions on hospitalization

and the extent of follow up (Table 33–4). Active bleeding, a vis-

ible vessel, and adherent clot are considered high-risk endo-

scopic signs. Endoscopic therapy is recommended for such

patients, and they need to be monitored closely for signs of

rebleeding. Indeed, without endoscopic therapy, an ulcer

found to be actively bleeding during the endoscopy has a 90%

rebleeding rate after bleeding stops spontaneously. On the

other hand, no endoscopic therapy is indicated for clean base

ulcers (low-risk finding). Such patients can be discharged

safely after endoscopy with close outpatient follow-up.

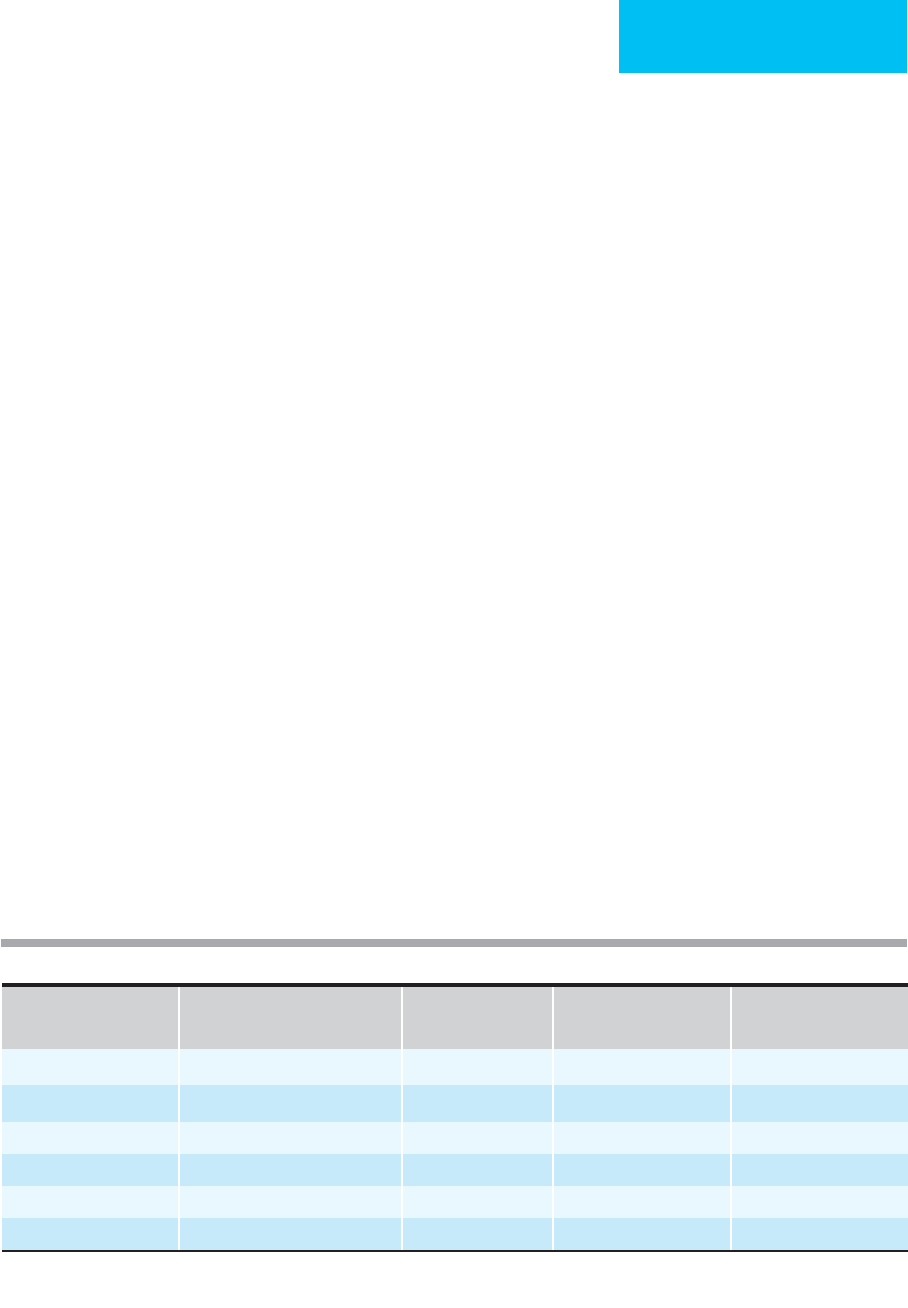

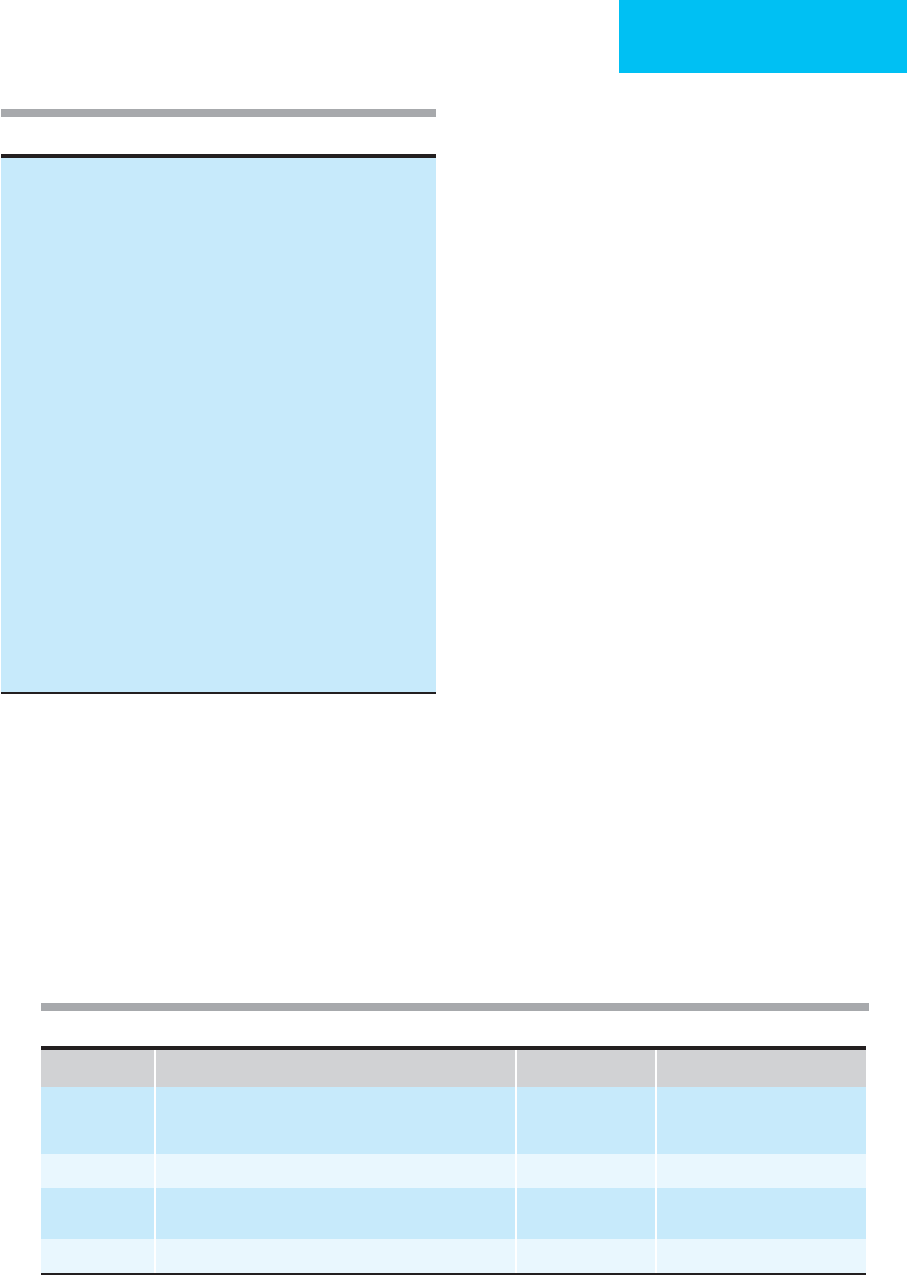

Endoscopic Stigmata Prevalence

Rebleeding Risk without

Endoscopic Therapy

Rebleeding Risk after

Endoscopic Therapy

High risk Active arterial bleeding 10% 90% 18%

Nonbleeding visible vessel 25% 40–50% 10–15%

Adherent clot 10–14% 25–35% 0–5%

Oozing without visible vessel 10% 10–20% <1%

Low risk Flat spot 10% 7% N/A

Clean-base ulcer 35% 3–5% N/A

Modified from Katschinski B et al: Dig Dis Sci 1994;39:706; and from Center for Ulcer Research and Education: Digestive Disease Research

Center, Hemostasis Research Group, UCLA School of Medicine and the West Los Angeles VA Medical Center.

Table 33–4. UGI bleeding: endoscopic stigmata and risk of rebleeding without and with endoscopic therapy.

CHAPTER 33

708

Modern endoscopic therapeutic techniques include injec-

tion of vasoconstrictive agents, thermal therapy, and use of

mechanical devices. Injection therapy employs a needle with

retractable tip, with epinephrine the most commonly used

agent. Injections are frequently combined with thermal ther-

apy. A bipolar coagulation or heater probe is physically com-

pressed against the bleeding vessel, and thermal energy then

seals the vessel wall. More recently, mechanical devices, in

particular endoscopic clips, are being used increasingly in

ulcer hemostasis. A number of studies have shown signifi-

cantly decreased rebleeding rates with the combination of

endoscopic clips and injection therapy compared with injec-

tion therapy alone. However, clips are difficult to place in a

scarred-down ulcer, and they also are more likely to fall off in

this situation. Overall, clip application is more operator- and

position-dependent than other modalities.

B. Pharmacologic Therapy for Peptic Ulcer Bleeding—

Pharmacologic therapy by acid suppression is the cornerstone

of peptic ulcer bleeding management. Indeed, clot lysis occurs

at pH less than 6, and platelet aggregation is enhanced at pH

greater than 6. Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are the main

acid suppressive agents. A high-dose PPI bolus followed by

continuous infusion is particularly efficacious after endo-

scopic therapy. A recent large double-blind, randomized trial

showed 6.7% versus 22.5% rebleeding rates in patients on con-

tinuous intravenous PPIs after endoscopic therapy compared

with placebo. PPIs also decreased rebleeding and surgery rates

compared with histamine-2 (H

2

) blockers. Data also support

the use of empirical high-dose PPI therapy prior to endoscopy.

H. pylori eradication is important in peptic ulcer bleeding

management, in particular for prevention of ulcer recur-

rence. H. pylori serology and antral biopsy are the preferred

tests in acute bleeding. H. pylori eradication should be con-

firmed after treatment with a urea breath test.

Intravenous octreotide has been studied in nonvariceal acute

UGI bleeding, but its effectiveness remains undetermined.

C. Recurrent Peptic Ulcer Bleeding and Endoscopic

Therapy Failures—Effective hemostasis is attained endo-

scopically in more than 95% of ulcers that are actively bleed-

ing or have high-risk endoscopic stigmata. However,

high-risk ulcers have a 15% risk of rebleeding, usually in the

first 72 hours after index bleed. Active spurting of blood and

large (>2 cm) ulcers were independent risk factors for endo-

scopic therapy failure in a recent prospective study.

Therefore, a “second look” endoscopy is usually indicated in

case of rebleeding, with a 73% rate of long-term hemostasis.

Failure of the second endoscopic therapy attempt should

initiate consideration for alternative treatments, in particular

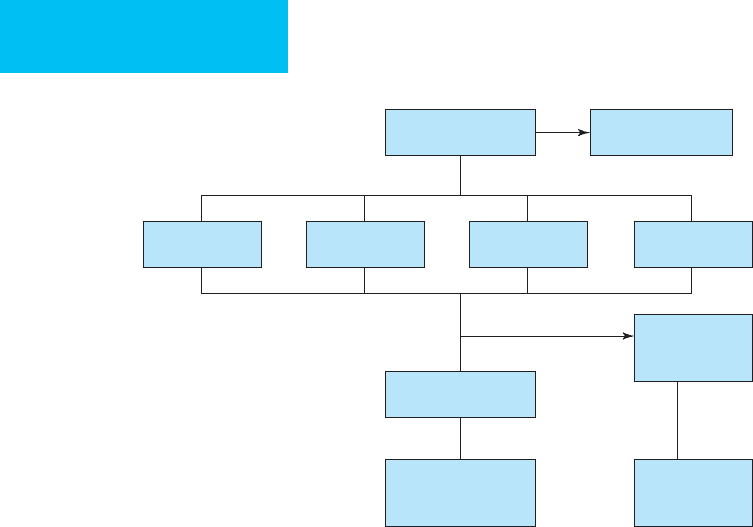

surgery (Figure 33–2). According to a recent large registry of

UGI bleeding cases, 6.5% of patients with bleeding peptic

ulcers underwent surgery for continued bleeding or rebleed-

ing. With the effective medical therapies available, the goal of

surgery is no longer ulcer cure but control of hemorrhage in

these patients. The choice of surgical procedure includes

simple oversewing of the ulcer (with or without vessel liga-

tion), ulcer excision, or radical surgery (ie, depending on

ulcer location, vagotomy with antrectomy or gastrectomy).

In a recent review of surgical options, conservative therapy

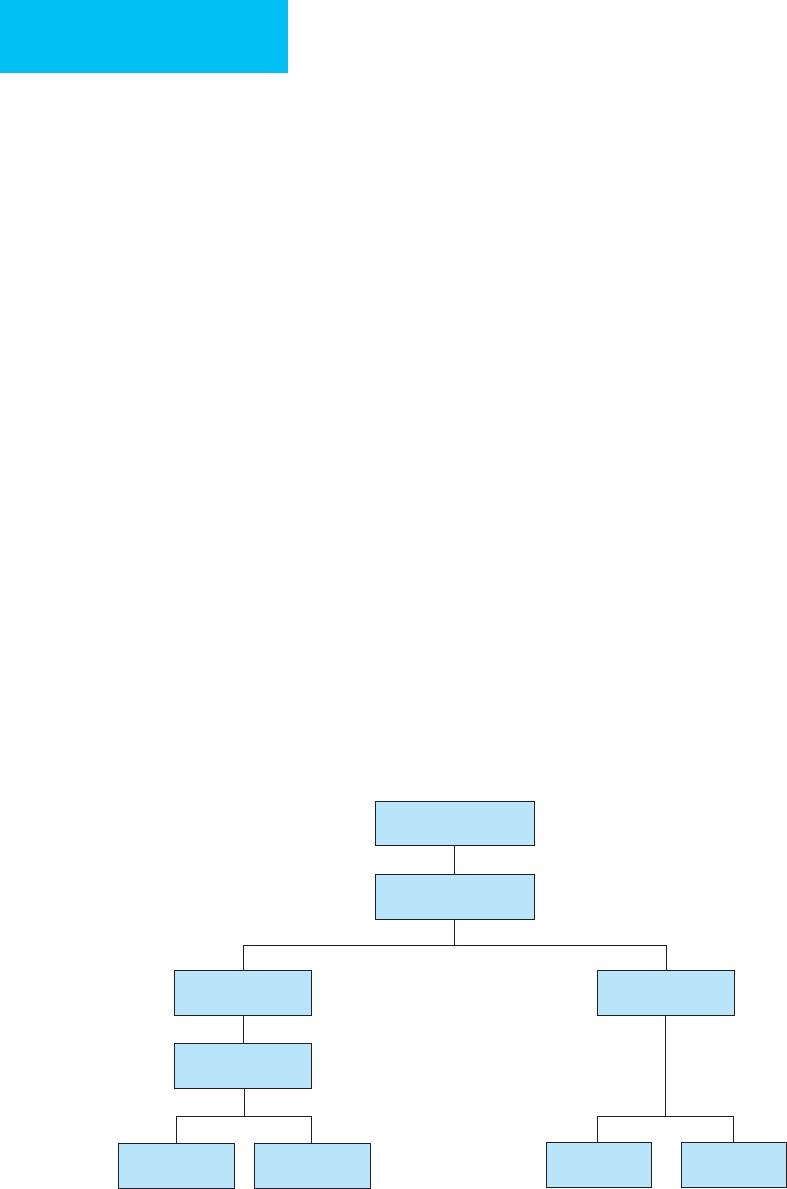

Continued bleeding

or early recurrence

Failed

repeat endoscopy

TIPS

1

Splenectomy

2

Shunt surgery

Surgery Angiography

Variceal bleeding

Nonvariceal

bleeding

Balloon

tamponade

1

Treatement of choice for gastric varices

2

Treatment of choice for isolated splenic vein thrombosis & gastric varices

Figure 33–2. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding: failures of endoscopic therapy.

GASTROINTESTINAL BLEEDING

709

with oversewing of the ulcer had rates of morbidity and mor-

tality comparable with those of more radical surgery.

However, rebleeding rate was somewhat higher. Current rec-

ommendations are for ulcer excision in patients with a bleed-

ing gastric ulcer, but gastric resection should be performed

for a large penetrating ulcer. Duodenal ulcers should be over-

sewn and vessel ligation performed.

Patients who are not surgical candidates can be considered

for a third endoscopic therapy attempt or for therapeutic

angiography. The latter showed a 50–90% success rate in

management of large gastroduodenal ulcers. Intraarterial

vasopressin infusion and embolization with microcoils, gela-

tin, or polyvinyl alcohol particles are the main angiographic

techniques in ulcer hemostasis. With selective catheterization,

complications of embolization such as bowel ischemia, perfo-

ration, abscess formation, and hepatic infarction are rare.

Variceal Bleeding

A. Endoscopic Diagnosis and Treatment of Variceal

Bleeding—Endoscopy is critical in all aspects of variceal

bleeding management: to identify the patients at risk, to pre-

vent a first bleed, to treat active bleeding, and to decrease the

risk of rebleeding. Both esophageal and gastric (near the car-

dia) varices can be treated endoscopically, with overall suc-

cess rates of about 90% (see Figure 33-1). However, gastric

varices often require additional treatment modalities to pre-

vent rebleeding.

Two endoscopic techniques are applied most often for

variceal bleeding hemostasis: sclerotherapy, which has been

in use for 60 years, and more recently, band ligation. In scle-

rotherapy, a sclerosant (routinely 5% ethanolamine) is

injected via a retractable-tip needle into the varix and/or sur-

rounding tissues, leading to coagulation necrosis and variceal

thrombosis. Repeated sclerotherapy can be performed until

there is complete eradication of esophageal varices. However,

sclerotherapy has been associated with 2–5% mortality and

up to a 20% major complication rate. Major complications

include deep ulcerations, stricture formation, esophageal

perforation, and mediastinitis. Transient bacteremia is com-

mon during sclerotherapy, and antibiotics should be given to

at-risk patients prior to sclerotherapy.

In recent years, band ligation has replaced sclerotherapy

as the primary endoscopic treatment of variceal bleeding,

and it is equally efficacious but much safer. In this procedure,

a rubber band is placed on the varix via a device attached to

the endoscope. The band effectively strangulates the varix,

resulting in varix thrombosis. Multiple bands can be

deployed in one setting. The effect of the band is local, and

systemic complications are rare. In several studies, band lig-

ation was compared with sclerotherapy for the prevention of

esophageal varices recurrence. Rebleeding rate and number

of sessions needed for variceal obliteration were significantly

lower with band ligation (6% and four sessions compared

with 21% and five sessions for sclerotherapy). On the other

hand, recurrence of varices at 1 year was less with sclerotherapy

(8% versus 29% for band ligation). Some experts recom-

mend combining band ligation and sclerotherapy at the final

therapy session to improve long-term eradication of varices.

B. Pharmacologic Therapy of Variceal Bleeding—

Pharmacologic therapy is a necessary component of variceal

bleeding management. Octreotide, a long-acting analogue of

somatostatin, is used most commonly owing to its safety and

ease of administration. Octreotide is thought to work, at least

in part, by decreasing splanchnic blood flow. Octreotide typ-

ically is given as a bolus followed by continuous infusion.

Optimal duration of therapy is not well defined, but 3–5 days

of administration after the bleeding episode is typically rec-

ommended. Octreotide, used in combination with endo-

scopic therapy, has been shown to significantly improve

short-term hemostasis rate (66% versus 55% for band liga-

tion alone).

Prophylactic use of antibiotics in cirrhotic patients with

UGI bleeding is another important aspect of variceal bleed-

ing management. Indeed, bacterial infections are found in up

to 20% of cirrhotic patients with UGI bleeding. Antibiotic

prophylaxis not only reduces infectious complications but

also has shown a trend toward improved mortality. The

choice of antibiotic and duration of therapy are not well

established. An oral quinolone is used commonly for 7–10

days after the bleeding episode.

Several uncontrolled studies suggest that acid suppres-

sion (ie, with a PPI) might be another useful addition to

endoscopic therapy, in particular in healing of postscle-

rotherapy or post–band ligation ulcers. Nonselective β-

blockers and nitrates have a limited role in acute variceal

bleeding setting and should be reserved for outpatient

rebleeding prevention.

C. Recurrent Variceal Bleeding and Endoscopic Therapy

Failures—In 10–20% of patients, combined endoscopic and

pharmacologic therapy fails to achieve long-term hemosta-

sis. The highest risk for rebleeding is in the first 48 hours, as

well as up to 6 weeks after the index bleed. Generally, repeat

endoscopy is recommended in early hemostasis failure.

Alternative endoscopic therapeutic modality should be

applied in these cases, such as sclerotherapy if initial band

ligation was unsuccessful.

Surgery and transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic

shunting (TIPS) are the two main treatment options for patients

who have failed endoscopic therapy (see Figure 33-2).

Balloon tamponade usually is attempted to address acute

severe bleeding until one of these options is chosen. The

Sengstaken-Blakemore tube, with both esophageal and gastric

balloons, is used most commonly for tamponade. Short-term

hemostasis rates vary from 30–90%, and rebleeding usually

occurs after balloon deflation. Balloon tamponade is associ-

ated with a number of significant complications, in particular

esophageal rupture and aspiration. To prevent these compli-

cations, the esophageal balloon should not be inflated for

more than 24 hours, and tamponade should be performed

only in patients with an endotracheal tube in place.

CHAPTER 33

710

Surgery is effective in variceal bleeding. Unfortunately,

most variceal bleeding patients present with decompensated

cirrhosis, making them poor surgical candidates. Nowadays,

both nonselective (ie, portocaval) and selective (ie, splenore-

nal) shunts are used for variceal bleeding control.

Nonshunting operations, such as gastroesophageal devascu-

larization (Sugiura procedure), are performed rarely.

Perioperative morbidity and mortality are quite high for

emergent shunt operations, and management is further com-

plicated by a 40–50% incidence of encephalopathy. Surgical

shunting also significantly alters vascular anatomy, making

future liver transplantation more challenging.

In recent years, TIPS has emerged as a safer and easier-

to-perform alternative to surgical shunting. TIPS is done

by an interventional radiologist and requires only local

anesthesia or light sedation. The stent is passed via the

transjugular route and connects the hepatic vein with an

intrahepatic portion of the portal vein, thus creating a por-

tosystemic shunt. TIPS is effective in more than 90% of

variceal bleeds. It is the treatment of choice for gastric

variceal bleeding because endoscopic therapy usually does

not prevent rebleeding of gastric varices. As with surgical

shunts, post-TIPS encephalopathy is common (~30% inci-

dence). Another limitation of TIPS is frequent stent

restenosis or thrombosis leading to multiple revisions and

restenting.

Baradarian R et al: Early intensive resuscitation of patients with

upper gastrointestinal bleeding decreases mortality. Am J

Gastroenterol 2004;99:619–22. [PMID: 15089891]

Barkun A et al: Consensus recommendations for managing

patients with nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Ann

Intern Med 2003;139:843–57. [PMID: 14623622]

Barkun A et al: The Canadian registry on nonvariceal upper gas-

trointestinal bleeding and endoscopy (RUGBE): Endoscopic

hemostasis and proton pump inhibition are associated with

improved outcomes in real-life setting. Am J Gastroenterol

2004;99:1238–46. [PMID: 15233660]

Chung IK et al: Endoscopic factors predisposing to rebleeding fol-

lowing endoscopic hemostasis in bleeding peptic ulcers.

Endoscopy 2001;33:969–75. [PMID: 11668406]

El-Serag HB, Everhart JE: Improved survival after variceal hemor-

rhage over an 11-year period in the Department of Veterans

Affairs. Am J Gastroenterol 2000;95:3566–73. [PMID: 11151893]

Imperiale TF et al: Predicting poor outcome from acute upper gas-

trointestinal hemorrhage. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:1291–6.

[PMID: 17592103]

Jensen DM et al: Randomized trial of medical or endoscopic ther-

apy to prevent recurrent ulcer hemorrhage in patients with

adherent clots. Gastroenterology 2002;123:407–13. [PMID:

12145792]

Kahi CJ et al: Endoscopic therapy versus medical therapy for

bleeding peptic ulcer with adherent clot: A meta-analysis.

Gastroenterology 2005;129:855–62. [PMID: 16143125]

Lau JY et al: Omeprazole before endoscopy in patients with gas-

trointestinal bleeding. N Engl J Med 2007;356:1631–40. [PMID:

17442905]

Ohmann C, Imhof M, Roher HD: Trends in peptic ulcer bleeding

and surgical treatment. World J Surg 2000;24:284–93. [PMID:

10658062]

Orozco H, Mercado MA: The evolution of portal hypertension

surgery: Lessons from 1000 operations and 50 Years’ experience.

Arch Surg 2000;135:1389–93. [PMID: 11115336]

Qureshi W et al: ASGE guideline: The role of endoscopy in the

management of variceal hemorrhage, updated July 2005.

Gastrointest Endosc 2005;62:651–5. [PMID: 16246673]

Soares-Weiser K et al: Antibiotic prophylaxis of bacterial infections

in cirrhotic inpatients: A meta-analysis of randomized, con-

trolled trials. Scand J Gastroenterol 2003;38:193–200. [PMID:

12678337]

Stabile BE, Stamos MJ: Surgical management of gastrointestinal

bleeding. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2000;29:189–222.

[PMID: 10752022]

Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Hematochezia (bright red or maroon stools).

Initial evaluation is similar for lower and upper GI

bleeding patients.

Patients younger than 50 years of age with self-limited

mild lower intestinal bleeding (most likely owing to

internal hemorrhoids) can be further evaluated with

colonoscopy or flexible sigmoidoscopy as outpatients.

Urgent colonoscopy is indicated in the presence of

unstable vital signs, continued bleeding, or more than

two comorbid conditions.

Life-threatening lower intestinal bleeding require con-

sideration of emergent angiography or surgery without

delaying for bowel preparation/colonoscopy.

General Considerations

Lower intestinal bleeding is characterized by a lesion location

distal to ligament of Treitz. Most often the source of bleeding

is colonic. Hematochezia (ie, bright red or maroon colored

stools) is the classic clinical presentation. Although severe

lower intestinal bleeding is less common than UGI bleeding,

it is a frequent GI emergency. On average, a full-time gas-

troenterologist sees more than 10 severe lower intestinal

bleeding cases per year.

Initial Approach, Resuscitation, and Risk

Stratification

The main principles of initial evaluation and resuscitation of

UGI bleeding apply equally to lower intestinal bleeding. The

goals are the same: to assess bleeding severity based on the

degree of hemodynamic compromise, to evaluate comorbid

illnesses, and to optimize the patient’s condition prior to

treatment. Syncope or postural hypotension is indicative of

GASTROINTESTINAL BLEEDING

711

potentially massive bleeding. In such cases, NG aspiration

should be performed to exclude an upper bleeding source. In

hematochezia without hemodynamic compromise, severe

UGI bleeding is unlikely, and NG tube placement might not

be necessary. After assessing bleeding severity, attention

should be paid to exacerbation of comorbid illnesses. In par-

ticular, evaluation for cardiac ischemia is important because

lower intestinal bleeding is frequent in elderly patients.

Resuscitation of lower and upper GI bleeding patients

involves similar approaches. As described earlier for UGI

bleeding, resuscitation aims to quickly restore intravascular

volume with crystalloids, colloids, and blood and to correct

hemostatic abnormalities, if present. Patients with severe

bleeding should be admitted to an ICU, and surgical consulta-

tion should be obtained early in the course of hospitalization.

In most patients, lower intestinal bleeding stops sponta-

neously. Thus it is crucial to identify patients who are at high

risk for continued bleeding. Commonly reported clinical

predictors are hypotension and tachycardia, continued rectal

bleeding during the first 4 hours of hospitalization, absence

of abdominal pain, use of aspirin, and presence of at least

two comorbid conditions. Prospective validation of this risk

stratification scheme showed 0% rebleeding in a low-risk

group compared with 77% in a high-risk group.

Causes of Lower Intestinal Bleeding

Diverticulosis, colitis (ie, ischemic, infectious, or postradia-

tion), cancer, and angiodysplasia are the main causes of

severe lower intestinal bleeding (Table 33–5). Hemorrhoids

are a frequent cause of rectal bleeding, especially in patients

younger than 50 years. However, hemorrhoidal bleeding is

rarely severe.

Diverticulosis is responsible for more than 30% of lower

intestinal bleeding. Colonic diverticula are mucosal and sub-

mucosal herniations through the muscle layer, thought to

develop owing to increased intraluminal pressure or

decreased colonic wall muscle tone. They are found in half the

adult population in the Western hemisphere, and the inci-

dence increases with age. Bleeding occurs in only 5–15% of

patients with diverticular disease. However, lower GI bleeding

can be massive in a third of those patients. Painless hema-

tochezia is the classic clinical presentation of diverticular

bleeding. In 75%, diverticular bleeding stops spontaneously,

but the risk of rebleeding is 25–38% in the following 4 years.

Colitis (inflammation of the colon) is another common

cause of severe lower intestinal bleeding. Of note, mortality

rates as high as 20–50% have been reported in hospitalized

patients with ischemic colitis bleeding. Hematochezia in

ischemic colitis is typically accompanied by mild abdominal

pain, differentiating it from painless diverticular bleeding.

The mechanism of mucosal ischemia is thought to be hypo-

perfusion of small intramural vessels rather than large vessel

occlusion. Ischemic colitis can occur throughout the colon,

but watershed areas such as at the splenic flexure or rectosig-

moid junction are affected most frequently. Ischemic colitis

sometimes occurs after extensive surgical procedures or as a

result of systemic hypotension.

Infectious and inflammatory colitis rarely cause severe

lower intestinal bleeding. However, infectious colitis, in par-

ticular secondary to Clostridium difficile, can mimic ischemic

colitis and should be excluded as part of the workup for

hematochezia and colitis.

Angiodysplasias (arteriovenous malformations) account

for about 8% of severe lower intestinal bleeding, but its inci-

dence has been decreasing in recent years. Angiodysplasia is

associated with renal failure and hereditary hemorrhagic

telangiectasia syndrome (Osler-Weber-Rendu syndrome).

An association with aortic stenosis is less clear.

Colon cancer typically presents with occult blood loss

rather than overt hematochezia. Severe lower intestinal

bleeding usually is caused by cancer ulceration, signifying an

advanced stage.

Diagnosis of Lower Intestinal Bleeding

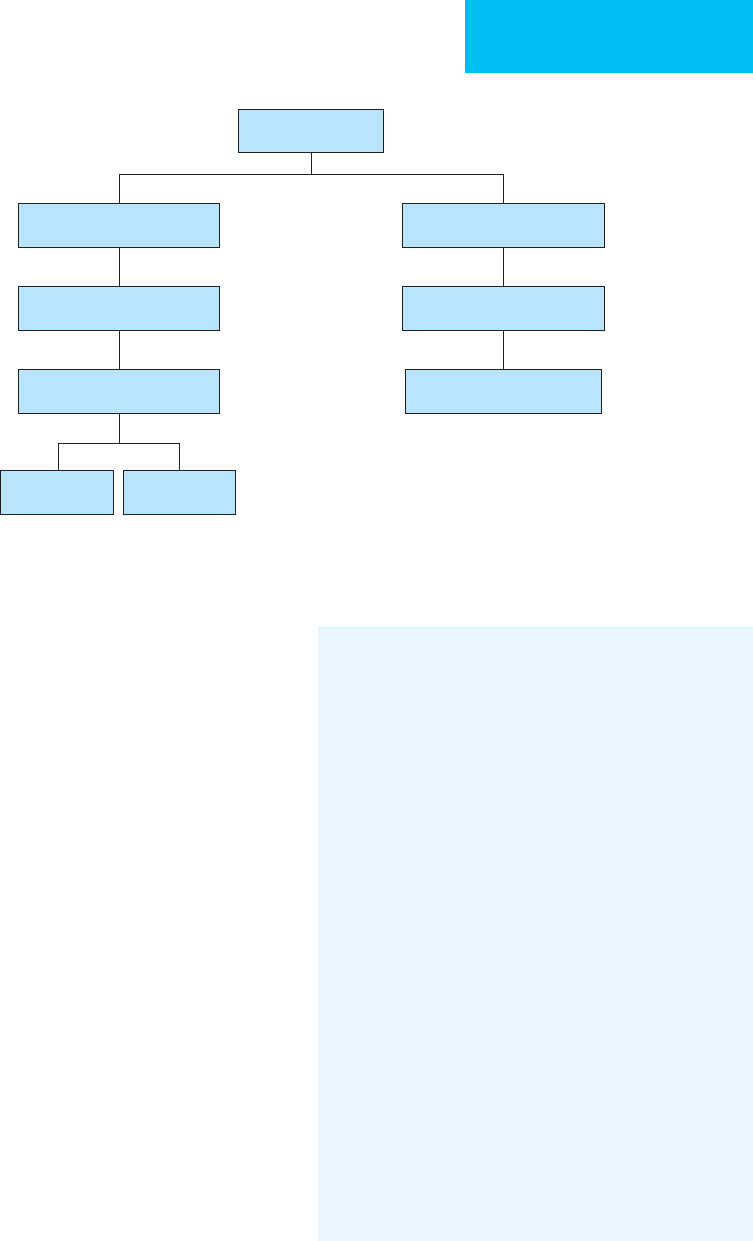

Colonoscopy is typically the first step in evaluation of

lower intestinal bleeding (Figure 33–3). Its main advantage

is that both diagnosis and treatment can be accomplished

in one procedure. However, downsides are the requirement

for bowel preparation and the small, albeit identifiable,

risk of sedation. Notably, management of severe life-

threatening lower intestinal bleeding (ie, angiography or

surgery) should not be delayed for bowel preparation/

colonoscopy. Some gastroenterologists perform colonoscopy

on unprepared bowel because blood is cathartic.

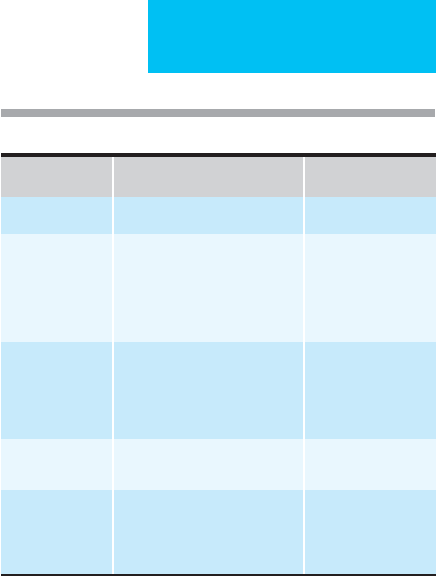

Table 33–5. Severe lower gastrointestinal bleeding: causes.

Relative Frequency

Anatomic Diverticulosis 33%

Vascular

malformations

Arteriovenous malformations

Idiopathic angiomas

Osler-Weber-Rendu syndrome

Radiation-induced

telangiectasia

Angiodysplasia, 8%

Inflammatory Ischemic colitis

Infectious colitis

Inflammatory bowel disease

Radiation colitis

18%

Neoplasm Polyps

Carcinoma

19%

Other Hemorrhoids

Ulcer

Postbiopsy, postpolypectomy

18%

CHAPTER 33

712

Occasionally, flexible sigmoidoscopy on unprepared bowel

is sufficient, in particular as a quick check for ischemic or

infectious colitis. In most cases, we recommend urgent

bowel purge with polyethylene glycol (4–6 L) over 3–5

hours via NG tube or orally. Metoclopramide can be used

in conjunction with the purge to improve gastric emptying

and decrease nausea. Sodium phosphate preparations

should not be used in the acute setting because of high

phosphate and sodium loads. Radiographic studies should

be obtained prior to the bowel preparation to rule out per-

foration or intestinal obstruction.

The overall diagnostic yield of colonoscopy in lower intes-

tinal bleeding is between 48% and 90% (mean 68%). There

are conflicting data on the optimal timing for colonoscopy.

One recent report suggests that diagnostic yield improves with

urgent colonoscopy. We usually perform colonoscopy for

severe lower intestinal bleeding within 6–12 hours of hospital-

ization, after resuscitation and bowel preparation.

Treatment of Lower Intestinal Bleeding

Although surgery is the most common treatment modality

for lower intestinal bleeding, endoscopic therapeutic options

have been expanding in recent years. In particular, bipolar

coagulation is used successfully for angiodysplasia bleeding.

In diverticular hemorrhage, a visible bleeding vessel or clot

(high-risk stigmata) can be treated with sclerotherapy and

bipolar coagulation similar to peptic ulcer bleeding. Use of

endoscopic clips in diverticular bleeding is currently under

investigation. Significantly decreased short- and long-term

rebleeding rates have been reported for endoscopic therapy

of diverticular bleeding. However, urgent colonoscopy and

experience in advanced endoscopic techniques are needed to

achieve high hemostasis success rates.

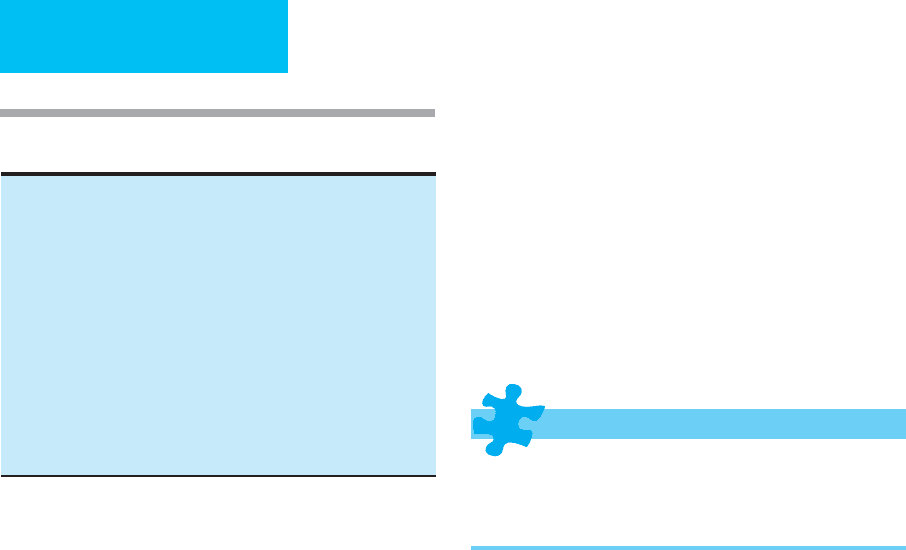

Failure of Endoscopic Diagnosis and Treatment

Radionuclide imaging typically is the next step in the local-

ization of a bleeding site after unsuccessful colonoscopy

(Figure 33–4). Radiolabeled red blood cells are injected

intravenously, and focal collections of radiolabeled material

are detected by scintigraphy. A 78% accuracy rate has been

reported, and bleeding as slow as 0.1–0.5 mL/min can be

identified. However, confirmatory colonoscopy is recom-

mended in the case of a positive radionuclide test owing to

rather high false-positive rates, typically a result of blood

from a UGI source collecting in the right colon.

Angiography is another diagnostic and therapeutic

modality used in case of colonoscopic failure. Angiography is

highly specific, but its sensitivity is significantly lower than

that of radionuclide imaging or colonoscopy. For angiogra-

phy to be positive, bleeding must be brisk, at a rate of more

than 1–1.5 mL/min. Since most lower GI bleeding stops

spontaneously, the timing of the angiography procedure is

particularly important. The overall diagnostic yield varies

widely from 12–69%. Some experts recommend radionu-

clide imaging prior to angiography to increase sensitivity.

However, this would further delay angiography and poten-

tially decrease its diagnostic yield.

After the bleeding site is identified angiographically, vaso-

pressin can be infused or a vessel can be selectively embolized

to stop the bleeding. Hemostasis rates of 91% have been

reported after intraarterial vasopressin in diverticular and

angiodysplasia bleeding. However, the rebleeding rate can be

Hematochezia

NG lavage

R/O upper source

>2

comorbidities

Continued

bleeding

Syncope

low SBP

Older

age

Urgent

purge

Urgent

colonoscopy

(within 6–12 hours)

Urgent

angiography/

surgery

Life-

threatening

bleeding

Figure 33–3. Management of lower gastrointestinal bleeding.

GASTROINTESTINAL BLEEDING

713

as high as 50%. Angiography also has a fairly significant (up

to 9%) rate of major complications, including intestinal

ischemia, contrast-induced renal failure, femoral artery

thrombosis, and transient ischemic attack.

Surgical Treatment

Surgery is recommended for continued bleeding (~10% of

all patients presenting with lower intestinal bleeding; see

Figure 33-4). If bleeding has been localized preoperatively,

segmental resection is performed with or without a stoma.

Reported surgical mortality is about 10%, mostly because of

comorbid conditions.

In the case of bleeding that cannot be localized, enteroscopy

and, if available, capsule endoscopy should be performed as a

final attempt to identify the bleeding site. If the bleeding lesion

is still not identified, a thorough surgical exploration is per-

formed, with examination and palpation of the entire small

intestine. If there is a significant amount of blood in the small

intestine, intraoperative endoscopy can be performed.

Exploratory laparotomy leads to localization of the bleeding

site in 78% of patients without preoperative diagnosis.

In the absence of an identified source of bleeding, subto-

tal colectomy is undertaken with ileorectal anastomosis or

ileostomy with Hartmann’s pouch. Emergent subtotal colec-

tomy carries significant morbidity (37%) and mortality

(11%). However, segmental colectomy without a definitive

source of bleeding is associated with an unacceptably high

30% rebleeding rate.

Bloomfeld RS, Rockey DC, Shetzline MA: Endoscopic therapy of

acute diverticular hemorrhage. Am J Gastroenterol 2001;96:

2367–72. [PMID: 11513176]

Brandt LJ, Boley SJ: AGA technical review on intestinal ischemia.

American Gastrointestinal Association. Gastroenterology

2000;118:954–68. [PMID: 10784596]

Green BT et al: Urgent colonoscopy for evaluation and manage-

ment of acute lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage: A random-

ized, controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol 2005;100:2395–402.

[PMID: 16279891]

Green BT, Rockey DC: Lower gastrointestinal bleeding:

Management. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2005;34:665–78.

[PMID: 16303576]

Hammond KL et al: Implications of negative technetium

99m–labeled red blood cell scintigraphy in patients presenting

with lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Surg 2007;193:404–7.

[PMID: 17320544]

Heil U, Jung M: The patient with recidivent obscure gastrointesti-

nal bleeding. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2007;21:

393–407. [PMID: 17544107]

Jensen DM et al: Urgent colonoscopy for the diagnosis and treat-

ment of severe diverticular hemorrhage. N Engl J Med

2000;342:78–82. [PMID: 10631275]

Strate LL et al: Validation of a clinical prediction rule for severe

acute lower intestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol 2005;100:

1821–7. [PMID: 16086720]

Strate LL, Syngal S: Predictors of utilization of early colonoscopy

vs radiography for severe lower intestinal bleeding. Gastrointest

Endosc 2005;61:46–52. [PMID: 15672055]

Strate LL: Lower GI bleeding: Epidemiology and diagnosis.

Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2005;34:643–64. [PMID:

16303575]

Failed endoscopic

diagnosis

Radionuclide imaging

identifies site

Failed endoscopic

therapy

Angiography

Segmental

colectomy

Subtotal

colectomy

1

Radionuclide imaging

fails to identify site

Confirmatory colonoscopy

endoscopic therapy

Enteroscopy

± capsule endoscopy

1

With intraoperative endoscopy

to exclude small bowel source

Figure 33–4. Lower gastrointestinal bleeding: failures of endoscopic diagnosis.

714

34

Hepatobiliary Disease

Hernan I. Vargas, MD

Liver disease is the ninth leading cause of death in the United

States, resulting in approximately 30,000 deaths each year.

Cirrhosis represents the final common pathway for a wide

variety of chronic liver diseases. Cirrhosis is defined as a dif-

fuse fibrotic process in the liver. Grossly abnormal nodules

replace the normally smooth hepatic parenchyma.

Patients with cirrhosis often develop complications from

their underlying liver disease such as upper GI bleeding,

renal insufficiency, ascites, or encephalopathy and require

critical care. In other circumstances, cirrhotic patients may

require critical care owing to unrelated problems such as

trauma, cancer, or major surgery. The physician caring for

patients in the ICU therefore should be knowledgeable about

disorders of liver function.

Acute Hepatic Failure

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Acute onset.

Jaundice.

Encephalopathy.

General Considerations

Acute hepatic failure is a rapid-onset, severe impairment of

liver function. The natural history is that of progressive dete-

rioration with multiple-system organ failure. Prior to the

availability of liver transplantation, the mortality was as high

as 80%.

The interval between the development of jaundice and

the onset of encephalopathy has been used to classify hepatic

failure as hyperacute (0–7 days), acute (8–28 days), and sub-

acute (28 days–12 weeks).

Acute viral hepatitis (ie, hepatitis B [HVB], and hepatitis A

[HVA]) and acetaminophen toxicity are the most common

causes of acute hepatic failure in the United States. Other

causes are as listed in Table 34–1.

Clinical Features

A. Symptoms and Signs—The onset of symptoms is usu-

ally abrupt, characterized by malaise, fatigue, and loss of

appetite. Less frequently, patients complain of abdominal

pain and fever. The physical examination is significant for the

presence of jaundice, hepatomegaly, and right upper quad-

rant tenderness.

Signs of developing encephalopathy range from mild per-

sonality change to confusion and deep coma. The presence of

encephalopathy is a precondition for a diagnosis of acute

hepatic failure. The severity of encephalopathy is measured

in four stages (Table 34–2).

Patients with encephalopathy stage III or stage IV com-

monly suffer from cerebral edema and increased intracra-

nial pressure. Cerebral edema is a common finding in

patients who die from acute hepatic failure. The pathogene-

sis of cerebral edema has not been clearly elucidated.

However, investigators have proposed a breakdown of the

blood-brain barrier as an important mechanism. Sodium

accumulation in the brain cells secondary to inhibition of

Na

+

,K

+

-ATPase also has been proposed. Cerebral edema

causes an acute rise in the intracranial pressure that

decreases perfusion pressure and cerebral blood flow.

Autoregulation of cerebral blood flow is lost.

Oliguria and generalized edema occur commonly and

are associated with higher mortality. They are typically

caused by hypovolemia, acute tubular necrosis, or hepatore-

nal syndrome.

Late in the course, patients may develop upper GI bleed-

ing and blood loss from the airways, puncture sites, and soft

tissues.

The clinical course of acute hepatic failure is frequently

complicated by bacterial and fungal infections. Infectious

complications are a major contributor to increased morbid-

ity and are the immediate cause of death in nearly half of

Copyright © 2008 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. Click here for terms of use.

HEPATOBILIARY DISEASE

715

fatal cases. The immune system is impaired by decreased

function of the reticuloendothelial system and complement

deficiency.

Coagulopathy may occur as a consequence of decreased

production of coagulation factors by the liver, as a conse-

quence of increased fibrinolysis, and from consumption, as in

disseminated intravascular coagulation. Thrombocytopenia

and platelet dysfunction are common.

Predictors of poor outcome are summarized in the King’s

College criteria (Table 34–3).

Treatment

Acute liver failure constitutes a medical emergency given the

high incidence of multisystem organ failure and the high

mortality. Patients with mild hepatic injury require mainte-

nance therapy with adequate hydration, euglycemia, and

electrolyte balance. Because the condition of patients with

more severe liver damage may deteriorate rapidly, respira-

tory support is often needed—particularly when cerebral

edema ensues.

A. Support Measures—

1. Encephalopathy and intracranial hypertension—

Cerebral herniation is a major cause of death if cerebral

edema and hypertension are untreated. Intracranial pressure

measurement is used for diagnosis of intracranial hyperten-

sion and monitoring of intracranial pressure dynamics. The

techniques for intracranial pressure monitoring are dis-

cussed in Chapter 31. Other monitoring techniques are

measurements of cerebral blood flow (with xenon) and cere-

bral oxygen consumption (by calculating the arterial-jugular

venous oxygen content difference).

The head of the bed is typically elevated 20–30 degrees to

reduce intracranial pressure, although the cerebral perfusion

pressure should be monitored to avoid an adverse impact

from a decrease in systemic pressure. Patients being main-

tained on ventilatory support are subjected to mild hyper-

ventilation to decrease cerebral hyperemia. Patient

stimulation must be minimized by premedication prior to

suctioning or postural changes in patients with severe

intracranial hypertension. A number of other measures may

decrease cerebral edema, such as mannitol (1 g/kg). Serum

osmolarity should be monitored. Mannitol is contraindi-

cated if the serum osmolarity is greater than 320 mOsm/L.

The use of barbiturates has been proposed as a means of

lowering intracranial pressure in combination with hypother-

mia. Barbiturates decrease cerebral metabolism and further

Table 34–1. Causes of acute hepatic failure.

Most common causes in USA

Acute viral hepatitis (HBV, HAV, HC)

Acetaminophen toxicity

Less common causes

Hepatitis D and E

Herpes simplex virus

Epstein-Barr virus

Drug toxicity

Antimicrobials (eg, ampicillin-clavulanate, ciprofloxacin,

erythromycin, isoniazid, tetracycline)

Sodium valproate

Lovastatin

Phenytoin

Tricyclic antidepressants

Halothane

Other toxins

Ecstasy (methylenedioxymethamphetamine)

Amanita phalloides (mushrooms)

Organic solvents

Herbal medicines (eg, ginseng, pennyroyal oil,

Teucrium polium

).

Miscellaneous causes

Acute fatty liver of pregnancy

Autoimmune hepatitis

Budd-Chiari syndrome

Reye’s syndrome

Wilson’s disease

Indeterminate

Stage Mental Status Tremor Electroencephalography

I Euphoria, occasionally depression; fluctuating mild confu-

sion; slowness of mentation and affect; slurred speech;

disorder in sleep rhythm

Slight Normal

II Drowsiness; inappropriate behavior. Present Generalized slowing

III Sleeps most of the time but is arousable, confused;

incoherent speech.

Present Abnormal

IV Unarousable Absent Abnormal

Table 34–2. Stages of encephalopathy.

CHAPTER 34

716

decrease cerebral blood flow and pressure. They also prevent

seizures. Barbiturate use is controversial, however, because of

their delayed metabolism owing to liver insufficiency.

2. Cardiovascular support—Patients with acute liver

insufficiency experience arteriovenous shunting and vasodi-

lation that causes tachycardia and hypotension. The

decreased clearance of vasoactive metabolites causes

decreased systemic vascular resistance and increased cardiac

output. Therefore, volume resuscitation and vasoactive drugs

may be necessary as support measures. With this hemody-

namic profile, an important differential diagnosis is sepsis.

3. Coagulopathy—Transfusion therapy is in general

reserved for patients with active bleeding. It is indicated also

prior to invasive procedures such as the placement of

intracranial pressure monitoring.

4. Renal failure—Renal failure is common in patients with

acute liver insufficiency. Maintenance of euvolemia is critical.

Avoidance of nephrotoxic drugs (ie, aminoglycosides) is

important. If renal azotemia ensues, dialysis may be needed.

Continuous venovenous dialysis or arteriovenous dialysis

methods are preferred to avoid hemodynamic changes and

hypotension associated with standard hemodialysis.

5. Respiratory failure—Airway intubation and mechani-

cal ventilation are frequently used as the encephalopathy

progresses to stage III. Acute respiratory distress syndrome

(ARDS) occurs in one-third of patients, causing hypoxemia.

B. Liver Transplantation—The mortality of severe acute

liver insufficiency in the absence of liver transplantation

approaches 80%. Survival after orthotopic liver transplanta-

tion has improved in recent years from 50% to more than

80% in selected series. Unfortunately, only 40–60% of

patients actually undergo transplantation owing to the short-

age of available organ donors.

Contraindications to liver transplantation are malig-

nancy, extrahepatic sepsis, irreversible brain injury from

intracranial hemorrhage, and unresponsive cerebral edema.

Bioartificial liver support is being investigated in selected

centers as a bridge to transplantation. Reports of hemoperfu-

sion, plasmapheresis, and extracorporeal perfusion exist, but

there has been limited success. Most recently, the develop-

ment of hybrid bioartificial support systems using hepato-

cytes from human or xenogeneic sources has shown some

promise.

Acute Gastrointestinal Bleeding

from Portal Hypertension

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Hematemesis, melena.

Stigmata of chronic liver disease.

Endoscopic evidence of bleeding varices.

General Considerations

Esophagogastric varices occur in 90% of patients with cir-

rhosis. Approximately one-third of these patients will experi-

ence GI bleeding, and between 30% and 50% of them will die

during each episode. It is not unexpected that bleeding from

esophagogastric varices accounts for one-third of all deaths

in patients with cirrhosis.

Esophagogastric varices are dilated intramural veins asso-

ciated with an extensive and tortuous capillary network.

They are alternative pathways of venous flow around the

increased vascular resistance in the intrahepatic and portal

system. They occur as a consequence of portal hypertension.

The development of varices is facilitated by systemic vasodi-

lation and decreased vascular resistance present in cirrhotics.

Clinical Features

A. Symptoms and Signs—Patients with acute bleeding

present with hematemesis. Patients with more chronic

bleeding present with melena and symptoms of anemia,

such as fatigue and weakness. Anemia may cause pallor and

tachycardia.

B. Laboratory Findings—Anemia occurs frequently.

Decreases in hemoglobin levels may not be detectable in an

early assessment of the bleeding. Evidence of chronic hepatic

dysfunction such as elevated serum aminotransferases,

bilirubin, and alkaline phosphatase is commonly present.

Differential Diagnosis

Patients with cirrhosis may experience an upper GI bleed

from other causes such as gastritis, peptic ulcer disease,

esophageal ulceration, or mucosal tears (Mallory-Weiss syn-

drome). Endoscopy is essential for diagnosis.

Table 34–3. Predictors of poor outcome in patients with

acute hepatic failure (King’s College criteria).

Acetaminophen toxic patients

Blood pH <7.30 (irrespective of grade of encephalopathy) or–

A combination of: encephalopathy stage III or IV, prothrombin time

>100 s (INR >6.5), and serum creatinine >3.4 mg/dL

Nonacetaminophen toxic patients

Prothrombin time >100 s (INR >6.5) (irrespective of stage of

encephalopathy) or–

Any three of the following five variables (irrespective of stage of

encephalopathy):

1. Age <10 years or >40 years

2. Etiology: hepatitis C, halothane hepatitis, idiosyncratic drug

reactions

3. Duration of jaundice before onset of encephalopathy of >7 days

4. Prothrombin time >50 s (INR >3.5)

5. Serum bilirubin level of >17.5 mg/dL