Bongard Frederic , Darryl Sue. Diagnosis and Treatment Critical Care

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

CRITICAL CARE OF NEUROLOGIC DISEASE

677

General Considerations

The initial patient examination should lead to an etiologic

diagnosis and selection of appropriate therapy. Infectious

disease consultation may be necessary in the process. Beyond

this, the critical care physician should be alert to certain

aspects and complications of CNS infections. Viral, granulo-

matous, parasitic, and bacterial infections each have special

features requiring consideration, and all have some common

features.

Clinical Features

A. Viral Infections—Meninges and neurons are the site of

most CNS viral infections; human immunodeficiency virus

(HIV), which infects microglia and leads to the formation of

multinucleated cells in the brain, is a notable exception. Viral

meningitis usually runs a self-limited course with supportive

therapy only, and the specific virus usually is not identified,

no more than headache, fever, neck stiffness, and abnormal

CSF findings are expected clinical features. On the other

hand, viral encephalitis reflects neuronal dysfunction. Altered

mental status, seizures, and even focal neurologic signs are

common. Early recognition is especially important in herpes

simplex type I (HSV) encephalitis because early and prompt

treatment with acyclovir improves outcome. This virus has a

predilection for temporal lobes; thus presenting features

commonly are confusion, change of usual behavior patterns,

memory disturbance, and complex partial seizures, which

may secondarily generalized (see section on seizures).

Inflammation, sometimes with a hemorrhagic component,

and edema may be enough to affect nearby cortex, giving rise

to additional focal features such as hemiparesis, sensory

deficit, or language disturbance. If HSV encephalitis is sus-

pected, acyclovir should be started immediately and not

postponed awaiting confirmatory workup.

HIV infection of the CNS may result in mental and motor

slowing (AIDS dementia complex) by mechanisms not yet

understood, but aside from the acute phase of infection, the

occurrence of seizures, focal neurologic symptoms, and find-

ings or symptoms and signs of meningitis indicate a super-

imposed complication such as infection with Toxoplasma,

Cryptococcus, fungus, or mycobacteria or an intracerebral

lymphoma.

B. Parasitic Infections—Cysticercosis is the most common

parasitic CNS infection encountered in the United States. It

is most common in states bordering Mexico and is seen

most often in Mexican immigrants. It is a major public

health problem in other parts of the world as well. It is

acquired by ingestion of eggs of the tapeworm Taenia, which

are shed in the feces of human carriers. Three forms of the

disease exist. The most common site of infection is the

parenchyma of the cerebral hemispheres, and the natural

course of this form of the disease is eventual death of the

organisms and subsequent calcification of the lesion, which

is readily identified as punctate calcifications on CT scans.

This process often is entirely asymptomatic, but sometimes

the tissue reaction and associated edema caused by the

organisms’ death produce focal neurologic symptoms and

signs, and imaging studies may not clearly distinguish such

a lesion from a primary or metastatic neoplasm. In this

instance, neurologic consultation is indicated. The charac-

teristic locus of parenchymal cysticercosis is at the gray-

white junction, and the usual clinical manifestation is a

seizure disorder, which sometimes is limited in time and

sometimes chronic. The seizures are partial, often with sec-

ondary generalization, which may be so rapid that the par-

tial onset is unrecognizable. Treatment with antiepileptic

medication is indicated.

Another form of this disease is intraventricular cysticer-

cosis, in which the organism remains cystic and is located

within the ventricular system. It is asymptomatic unless it

causes obstructive hydrocephalus with headaches as the ini-

tial symptom. This is a very dangerous situation because the

cysts often are free to move within a ventricle and thus can

cause acute hydrocephalus and relatively sudden and unex-

pected death of the patient. A high degree of suspicion is nec-

essary and should lead to brain imaging studies, which could

include CT brain scan, intraventricular positive-contrast CT

brain scan to outline a cyst, and MRI of the brain.

Neurosurgical intervention for shunting of CSF or cyst

removal is required.

Finally, the organism may reside in the subarachnoid

space, where it exists in the racemose form and can cause

meningeal inflammation. This is an indolent and chronic

form, and racemose membrane formation with cystic locula-

tions usually is slowly progressive. If this occurs around the

base of the brain, it also may result in obstructive hydro-

cephalus and require placement of a CSF shunt. Nonsteroidal

anti-inflammatory medication is indicated for relief of

headache owing to the meningeal reaction and may decrease

the inflammatory response.

Praziquantel or albendazole will kill the organism in the

parenchymal form and perhaps the racemose form, but no

controlled evidence exists that treatment with these agents

changes the natural outcome of the disease. Furthermore, the

increased rate of organism death and the subsequent brain

tissue reaction have increased patient morbidity and in some

instances, particularly when the disease was present in the

posterior fossa and around the brain stem, have contributed

to death of the patient.

Amebic meningoencephalitis occurs but is rare in the

United States. Usually it is acquired from swimming or

bathing in infected fresh warm water springs. Fever,

headache, and seizures are the presenting signs. Amphotericin

B has been recommended for treatment.

Toxoplasmosis—infection with Toxoplasma gondii, an

obligate intracellular parasite—is one of the most frequent

opportunistic infections in patients with AIDS and as a con-

sequence is encountered much more frequently than it used

CHAPTER 30

678

to be. Symptoms are those of meningoencephalitis and often

include headache, confusion, delirium, obtundation, and less

often, seizure. Brain imaging studies and CSF examination,

including serum Toxoplasma IgG antibody titer, are useful in

diagnosis, but sometimes a favorable response to treatment

with pyrimethamine and sulfadiazine (usually judged by

reduction of lesions seen on imaging studies) is necessary for

diagnostic confirmation. Brain biopsy will be diagnostic if

response to treatment is uncertain or fails.

C. Granulomatous Infections—Among fungi and yeast

infections, coccidioidomycosis and cryptococcosis are

encountered most frequently. While their infectious agents

and mycobacteria may form parenchymal lesions, a chronic

progressive meningitis is the rule, and it has a predilection

for meninges at the base of the brain. A common complica-

tion is the development of hydrocephalus owing to blockage

of CSF flow from the foramina of Luschka and Magendie. It

is usually a relatively slow and progressive process, occurring

in the middle to later stages of these diseases, and it often

requires placement of a CSF shunt. Brain CT scan or MRI

will show the presence and progression of hydrocephalus.

With contrast material, those studies also show the presence

of the inflammatory basilar meningitis. Other complications

are cranial nerve deficits and infarctions caused by inflam-

mation and constriction from the proliferative meningitis

around arteries. Fluconazole and intravenous amphotericin B

are the primary drugs for treatment of coccidioidomycosis

and cryptococcosis, but sometimes the response is insuffi-

cient, and intrathecal administration of amphotericin B is

necessary. One must be aware that if the drug is delivered

into a lateral ventricle in the presence of hydrocephalus and

a shunt, it will not reach the site of infection but rather be

diverted away. Under these circumstances, placement of a

reservoir for delivery into the foramen magnum or lumbar

subarachnoid space may be possible. This will require neuro-

surgical consultation.

D. Bacterial Infections—CNS infection with Listeria mono-

cytogenes is singled out here because it is unusual in that it

can cause a rhombencephalitis with prominent brain stem

findings, and it also may cause meningitis. Persons with

chronic illness are predisposed to this disease. In general,

prompt diagnosis and appropriate therapy of bacterial infec-

tions can prevent or reduce complications.

When seizures or focal neurologic deficits occur in the

course of bacterial meningitis, one should suspect cortical

vein thrombosis, which can be demonstrated by brain imag-

ing studies. In the case of seizures, an antiepileptic drug such

as phenytoin or phenobarbital should be administered and

probably will have to be given intravenously (see section on

seizures). Acute sagittal sinus thrombosis is a life-threatening

complication because of brain swelling and bleeding into the

parenchyma; neurologic findings can include obtundation

and signs of increased intracranial pressure, seizures, and

perhaps focal neurologic deficits—typically paresis of the

legs because of the functional localization of the area of brain

drained by the sinus. CT scan or MRI will confirm the diag-

nosis. Administration of an anticoagulant may diminish

clotting but may serve to increase bleeding from veins feed-

ing the sinus. Seizures should be treated with an antiepilep-

tic drug. As prompt a resolution as possible of the underlying

infection will improve outcome.

Hydrocephalus can be an early or late complication of

bacterial meningitis. Impairment of CSF absorption at the

arachnoid granulations caused by purulent accumulation,

inflammation, and adhesions is a significant factor in this

case. CSF shunting may be necessary.

Neurologic features of bacterial brain abscesses characteris-

tically are focal neurologic findings and seizures. These

abscesses often develop because of cardiac or pulmonary right-

to-left shunting or extension of a sinus infection. In addition to

antibiotic therapy, neurosurgical drainage and excision may be

necessary. The dreaded complication is rupture of an abscess

into the ventricles; this results in an acute ventriculitis, which

almost always is fatal. Because of postinfectious scarring and

gliosis, a chronic seizure disorder can develop.

Lastly, it is notable that a partially treated bacterial

meningitis can mimic viral meningitis.

E. Laboratory Findings—The EEG should be normal in

viral meningitis, but it is highly likely to be abnormal in viral

encephalitis, showing generalized slowing and, sometimes,

epileptiform events. Characteristic of herpes encephalitis are

periodic seizure discharges, predominant over the affected

temporal area; absence of this finding does not rule out her-

pes encephalitis. Hydrocephalus, especially from disease in

the posterior fossa, can show background disorganization

and slowing with intermittent runs of high-voltage slow

waves. Any focal brain disease may result in focal slow activ-

ity in the EEG, and often it is especially prominent in brain

abscesses. The presence of epileptiform discharges will con-

firm the diagnosis of seizures and, if focal, indicate the site of

the epileptogenic process.

The CSF examination will show an increased cellular con-

tent in all active meningeal infections, although rarely the

specimen may be obtained just preceding the cellular

response; in this case, another specimen after a day or so

should show increased cells. In general, bacterial infections

will show polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs) and the

other infections predominantly mononuclear cells. Some

viral infections, notably herpes simplex, may show a signifi-

cant proportion of PMNs early in the course of the disease.

It is typical in herpes encephalitis for the CSF to contain red

blood cells, but their absence does not rule it out. Partially

treated bacterial meningitis can show predominantly

mononuclear cells. Eosinophils are found occasionally in

cases of cysticercosis. The organism can be demonstrated by

India ink preparation in cryptococcosis and by wet prepara-

tion in amebic infection, but not finding them does not rule

out either one. The Gram stain may find bacteria and the

acid-fast stain mycobacteria. Low CSF glucose results from

infections interfering with its transport into the CSF, and it is

CRITICAL CARE OF NEUROLOGIC DISEASE

679

characteristically quite low in bacterial, fungal, and tubercu-

lous meningitis. It is usually little altered in viral meningitis.

Since the CSF glucose level is normally close to half the blood

glucose level, significantly high or low blood glucose can

confuse the issue. CSF glucose concentration lags behind

blood glucose 1–2 hours, but a blood glucose measured near

the time of obtaining the CSF specimen is usually satisfac-

tory for judging the CSF level. In viral infections, the CSF

protein content, like the glucose, is little altered, whereas it is

elevated in the other infections. If the protein content is very

high, blockage and impairment of CSF flow should be sus-

pected. Culture of CSF can provide a definitive diagnosis in

most infections other than viral, in which it is unusual to

recover the agent. Anaerobic organisms are common in brain

abscesses. Frequently the best management is to initiate

appropriate therapy while awaiting the results of culture.

Serologic tests of CSF include latex agglutination or other

techniques for detection of bacteria-specific antigens (usu-

ally available as a panel), measurement of cryptococcal anti-

gen, and assay of coccidioidal antibody titer—the latter two

are useful to follow as an index of response to treatment.

False-negative immunologic tests frequently are encountered

in neurocysticercosis, and a positive test may be found in

extraneural cysticercosis, so the practical value of such test-

ing is limited. Serum-specific HSV antibody titers rising over

the course of the illness can confirm the diagnosis, but usu-

ally in retrospect. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing

for CSF herpes simplex antigen has rarely been helpful in the

authors’ experience. Toxoplasma IgM titer is helpful if posi-

tive; a negative result does not exclude the disease in AIDS.

HIV infection of the CNS can be accurately followed by

assaying the CSF viral load.

REFERENCES

Adams HP Jr et al: Guidelines for the early management of patients

with ischemic stroke. Stroke 2003;34:1056–83. [PMID: 12677087]

Antithrombotic Trialists’ Collaboration: Collaborative meta-analysis

of randomised trials of antiplatelet therapy for prevention of

death, myocardial infarction, and stroke in high risk patients. Br

Med J 2002;324:71–86. [Note: The last sentence of this article has

been corrected to read “for most healthy individuals, however, for

whom a risk of a vascular event is likely to be substantially less

than 1% a year, daily aspirin may well be inappropriate” (rather

than appropriate).]

Barohn RJ: Approach to peripheral neuropathy and neuronopathy.

Semin Neurol 1998;18:7–18. [PMID: 9562663]

Broderick JP et al: Guidelines for the management of spontaneous

intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke 1999;30:905–15. [PMID:

10187901]

Drachman DB: Myasthenia gravis (medical progress). N Engl J Med

1994;330:1797–1810. [PMID: 8190158]

Hamel MB et al: Identification of comatose patients at high risk for

death or severe disability. JAMA 1995;273:1842–8. [PMID:

7776500]

Keys PA, Blume RP: Therapeutic strategies for myasthenia gravis.

DICP 1991;25:1101–8. [PMID: 1803801]

Medical Consultants to the President’s Commission for the Study of

Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavioral

Research: Guidelines for the determination of death. Neurology

1982;32:395–99.

Plum F, Posner JB: The Diagnosis of Stupor and Coma, 3rd ed. New

York: Davis, 1982.

Qureshi AI: Endovascular treatment of cerebrovascular diseases and

intracranial neoplasms. Lancet 2004;363:804–13. [PMID: 15016492]

Van Ness PC: Pentobarbital and EEG burst suppression in treatment

of status epilepticus refractory to benzodiazepines and phenytoin.

Epilepsia 1990;31:61–67. [PMID: 2303014]

680

00

Neurosurgical critical care covers a wide array of disorders

with varying pathophysiologic features. These conditions

also may be associated with unique complications that must

be recognized and treated promptly. Physicians involved in

the ICU management of neurosurgical patients therefore

must be familiar with the clinical features, complications,

and treatment of CSN disorders.

This chapter focuses on the management of patients with

head injury, aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage, brain

tumor, and cervical spinal cord injury. These disorders com-

prise the majority of neurosurgical ICU admissions.

Following injury, the CNS is vulnerable to a variety of sec-

ondary insults that can occur minutes, hours, or days following

the primary injury. Systemic conditions such as hypoxia,

hypotension, and electrolyte disorders may result in morbidity in

severely injured patients. Cerebral complications such as elevated

intracranial pressure, seizure, hemorrhage, and ischemia also

have the potential to cause neurologic impairment. The main

focus of current intensive care is to avoid or quickly reverse con-

ditions that can lead to secondary injury. Therefore, meticulous

management of all aspects of critical care is required to prevent

increased neurologic damage and improve patient outcome.

Head Injuries

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Signs depend on severity and anatomic location.

Concussion: transient loss of consciousness, memory

loss, headache, autonomic dysfunction.

Herniation: depressed level of consciousness, anisocoria,

abnormal motor findings.

General Considerations

Injuries to the brain remain the most common cause of

trauma-related death and disability. More than 500,000 peo-

ple suffer some degree of head trauma annually in the United

States. In the past, patients with traumatic brain injuries were

viewed with pessimism because both surgical and medical

therapeutic resources were limited. However, with recent

advances, including prompt, intensive management of head-

injured patients, the outcome has improved. One of the

major reasons for the better results has been improved criti-

cal care management, particularly the recognition and pre-

vention of disorders that cause secondary brain injury.

Classification

A. Primary Injuries—By definition, primary traumatic brain

injury occurs at the time of impact. This may lead to irre-

versible damage from cell disruption depending on the mech-

anism and severity of the inciting event. Head trauma may

cause damage to the scalp, skull, and underlying brain. Scalp

lacerations can cause significant hemorrhage, but in most

cases hemostasis can be achieved easily. Fractures are classi-

fied as linear, depressed, compound, or involving the skull

base. Linear or simple skull fractures require no specific treat-

ment. Depressed skull fracture occurs when the outer table of

the skull is depressed below the inner table and may result in

tearing of the dura or laceration of the brain. Operative repair

may be required, especially if the depressed fracture involves

the posterior wall of the frontal sinus or is associated with

intracranial hematoma. Compound depressed fractures are

defined as those associated with laceration of the overlying

scalp and are treated by surgical wound debridement and

fracture elevation, if severe. Basal skull fractures, which may

be diagnosed by the clinical findings of periorbital ecchymo-

sis (“raccoon eyes”), ecchymosis of the postauricular area

(Battle’s sign), hemotympanum, or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)

leak, may be complicated by meningitis or brain abscess.

Patients suffering from skull fractures have an increased risk

31

Neurosurgical Critical Care

∗

Duncan Q. McBride, MD

∗

Chris A. Lycette, MD, Curtis Doberstein, MD, Gerald E. Rodts, Jr.,

MD, and Duncan Q. McBride, MD, were the authors of this chapter

in the second edition.

Copyright © 2008 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. Click here for terms of use.

NEUROSURGICAL CRITICAL CARE

681

of delayed intracranial hematoma and should be observed for

12–24 hours after the initial injury.

Brain injury can occur directly under the injury site (coup

injury), but because the brain may move relative to the skull

and dura, compression of the brain remote from the site of

impact also can occur. This explains why brain injury can occur

in intracranial regions opposite the point of impact (contrecoup

injury). Craniocerebral trauma can cause concussion, cerebral

contusion, intracranial hemorrhage, or diffuse axonal injury.

1. Concussion—Concussion is an episode of transient loss

of consciousness following craniocerebral trauma. There is

no evidence of pathologic brain damage. Patients may suffer

from variable degrees of memory loss, autonomic dysfunc-

tion, headaches, tinnitus, and irritability.

2. Cerebral contusions—Cerebral contusions are hetero-

geneous areas of hemorrhage into the brain parenchyma and

may produce neurologic deficits depending on their anatomic

location. The anterior portions of the frontal and temporal

lobes are particularly vulnerable because of the rough contour

of the skull in these regions. Contusions are often associated

with disruption of the blood-brain barrier and may be com-

plicated by extension of the hemorrhage, edema formation, or

seizure. Large contusions can cause a mass effect resulting in

elevation of intracranial pressure or brain herniation.

3. Intracranial hematomas—Head injury may cause hem-

orrhage into the epidural, subdural, or subarachnoid spaces.

This bleeding, which may require surgical evacuation depend-

ing on its size and location, is usually diagnosed prior to admis-

sion to the ICU. However, delayed intracranial hematomas or

postoperative hematomas are not uncommon following cran-

iocerebral trauma and can develop and progress during ICU

observation. Intracranial bleeding may result in mass effect that

can cause intracranial pressure elevation (see below) and brain

herniation with compression of vital cerebral structures.

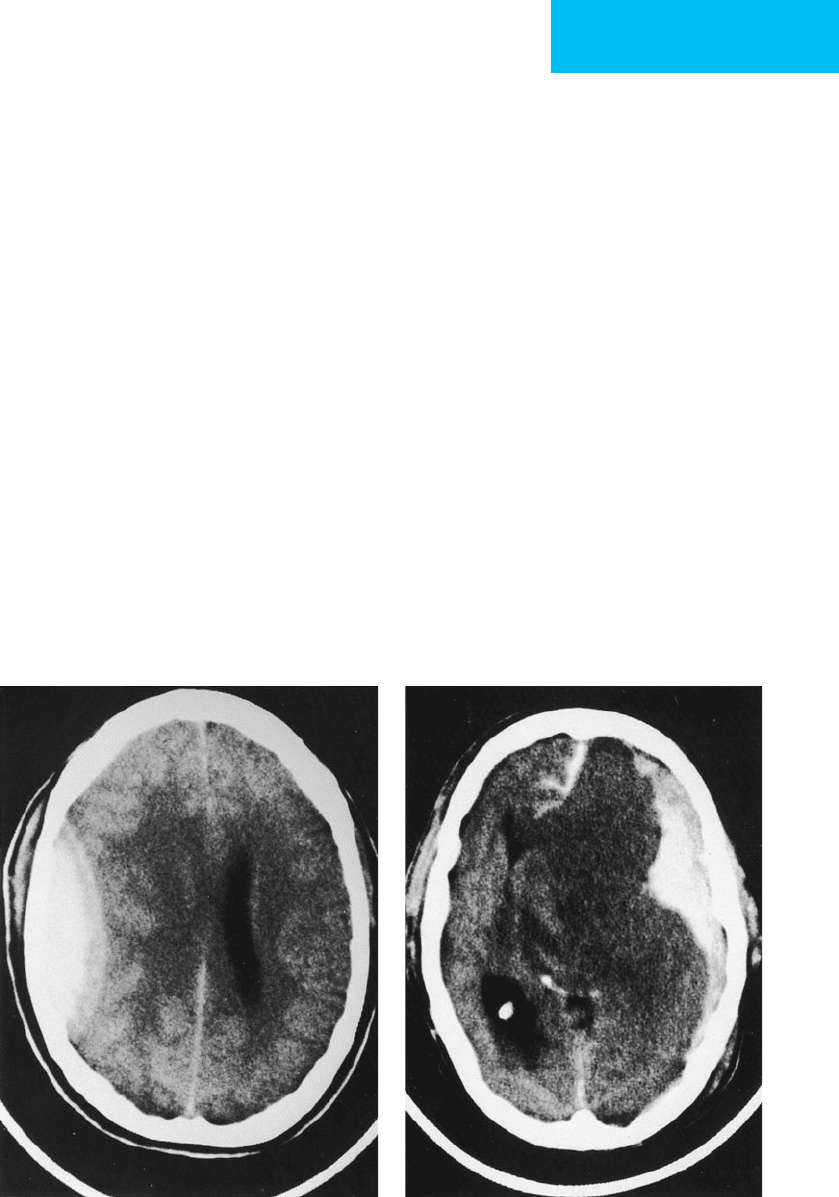

a. Epidural hematoma—This lesion is typically associated

with skull fracture and laceration of a meningeal vessel, most

commonly the posterior branch of the middle meningeal

artery. This may occur following low-velocity impact

injuries. Because the dura is firmly tethered to the inner table

of the skull, the hematoma usually takes on a homogeneous

lentiform configuration (Figure 31–1A).

b. Subdural hematoma—Subdural hematoma can be sec-

ondary to tearing of the cortical vessels, such as the bridging

veins that drain from the cortex to the dura and superior sagittal

sinus. It is commonly associated with other injuries such as cere-

bral contusions and has a worse prognosis than epidural

hematoma. Because it is not contained by dural attachments, the

hemorrhage often spreads diffusely across the cortical surface

resulting in a crescent-shaped image on CT scan (Figure 31–1B).

AB

Figure 31–1.

A.

Left temporoparietal epidural hematoma with obliteration of the left lateral ventricle and midline

shift.

B.

Right frontoparietal and interhemispheric subdural hematoma with massive right-to-left midline shift.

CHAPTER 31

682

c. Subarachnoid hemorrhage—Subarachnoid hemor-

rhage is caused most commonly by craniocerebral trauma.

The subarachnoid bleeding itself does not usually cause neu-

rologic damage, but hydrocephalus and cerebral vasospasm,

which are delayed complications, can lead to neurologic

impairment. Subarachnoid hemorrhage as a result of a rup-

tured intracranial aneurysm always should be considered as

a possible causative factor in trauma and needs to be ruled

out with an angiogram if there is reasonable concern.

4. Diffuse axonal injury—Diffuse axonal injury is shear-

ing of brain tissue with disruption of neuronal axon projec-

tions in the cerebral white matter resulting from rotational

deceleration of the brain. This diffuse injury to axons occurs

microscopically and can result in severe neurologic impair-

ment. Evidence of diffuse axonal injury is often not demonstra-

ble on CT scan. However, macroscopic hemorrhagic lesions

can be seen in deep brain structures such as the corpus callo-

sum or brain stem in association with diffuse axonal injury.

B. Secondary Injuries—Many studies have observed that

cerebral autoregulation is impaired after traumatic brain

injury. This causes patients with head injuries to be unusu-

ally vulnerable to secondary ischemic insults such as

hypotension, intracranial hypertension, and hypoxia.

Further ischemic damage often can be prevented with an

understanding of the pathophysiology of these secondary

insults and an aggressive targeted management protocol.

These conditions can be conveniently divided into intracra-

nial and systemic disorders (Table 31–1). Following traumatic

brain injury, some cells are directly and irreversibly damaged.

However, other cells may be functionally compromised and

not mechanically disrupted. These may recover if provided

with an optimal environment for survival. Compromised

cells are vulnerable to the pathophysiologic challenges

imposed by secondary insults. Prevention or rapid recogni-

tion and treatment of secondary insults is the primary focus

of modern critical care management of head-injured patients.

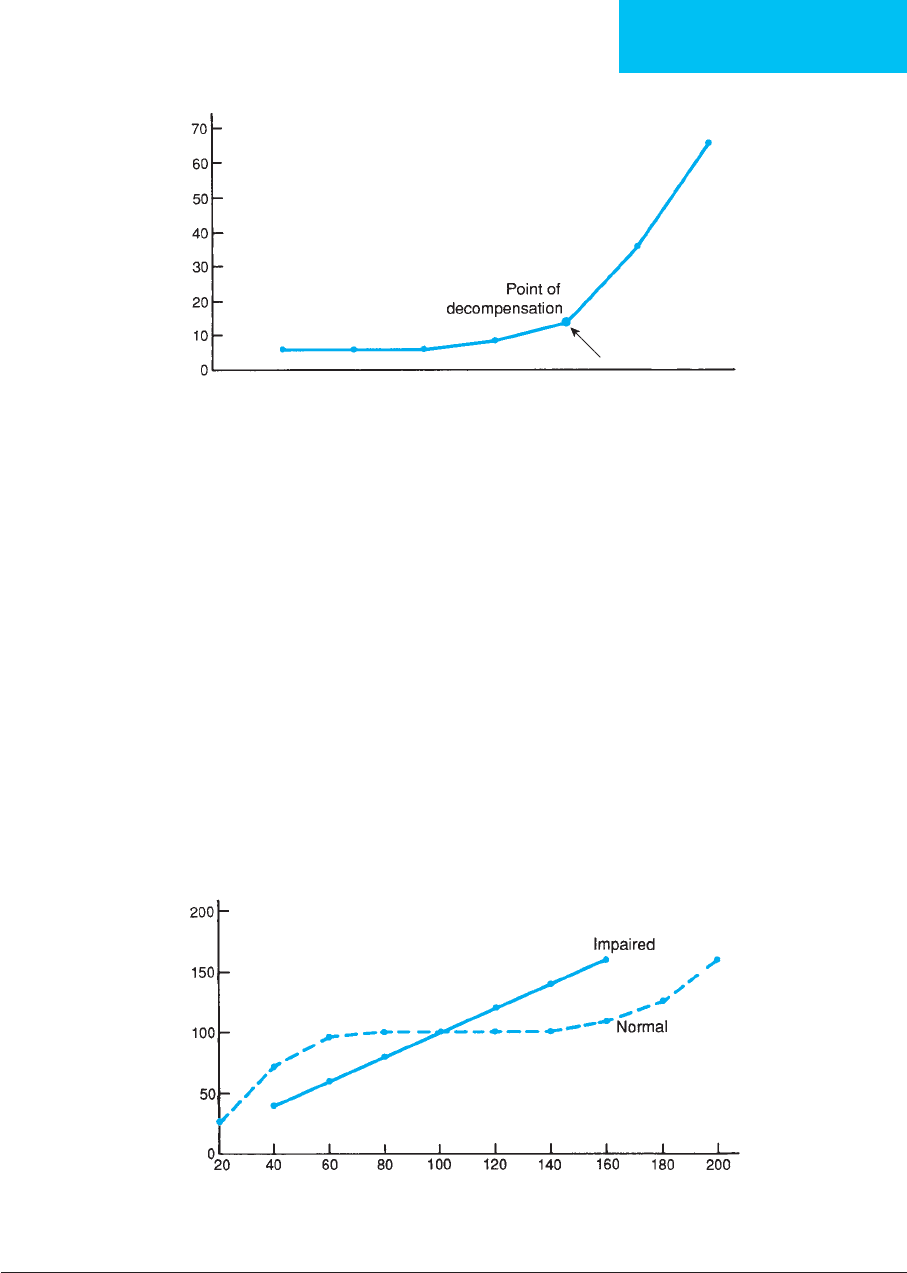

1. Secondary intracranial insults (raised intracra-

nial pressure)—Intracranial hypertension following cran-

iocerebral trauma may be caused by intracranial hematomas,

cerebral edema, or cerebral hyperemia. The Monro-Kellie

doctrine proposes that small increments in intracranial vol-

ume ultimately may cause intracranial pressure (ICP) to rise

because of the rigid and inelastic properties of the skull.

Under normal circumstances, intracranial volume is com-

posed of roughly 80% brain tissue, 10% CSF, and 10% blood.

An increase in volume of one of these compartments—or the

addition of a new pathologic compartment (eg, intracranial

hematoma)—must be compensated for by a reduction in the

volume of another compartment to maintain pressure.

Compensatory mechanisms that buffer such volume changes

include increased CSF absorption, redistribution of CSF

from the intracranial cavity into the spinal subarachnoid

space, and a reduction in cerebral blood volume. Cerebral

compliance relates the change in intracranial volume to the

resulting change in ICP (Figure 31–2). High compliance

signifies a system that can use buffering mechanisms to keep

ICP stable with changes in intracranial volume. However,

when the buffering becomes saturated, large pressure eleva-

tions result from small volume changes (poor compliance;

arrow in Figure 31–2). Therefore, although ICP may lie

within a relatively normal range (up to 20 mm Hg), a low-

compliance state may exist, and rapid elevations in ICP may

result from small increases in intracranial volume.

The falx cerebri, tentorium cerebelli, and foramen mag-

num are relatively rigid structures that compartmentalize

regions of the brain. Because many pathologic processes are

focal, pressure gradients can be generated between the

intracranial compartments. Elevated ICP may exert its delete-

rious effect by causing pressure gradients between different

brain compartments. If this pressure gradient is of sufficient

magnitude, shifting or herniation of brain tissue occurs and

can result in compression of vital structures. For example,

transtentorial herniation occurs when increased supratentorial

volume and pressure are sufficient to shift the uncus and the

medial portion of the temporal lobe through the tentorial

notch, causing compression and dysfunction of the midbrain

and oculomotor nerve. Compression of the medulla occurs

Table 31–1. Secondary insults.

Intracranial

Raised intracranial pressure

Delayed intracerebral hematoma

Edema

Hyperemia

Carotid artery dissection

Seizures

Vasospasm

Systemic

Hypoxia

Respiratory arrest

Airway obstruction

ARDS

Aspiration pneumonia

Pneumonia and hemothorax

Pulmonary contusion

Hypotension

Shock

Excessive bleeding

Myocardial infarction

Cardiac contusion or tamponade

Spinal cord injury

Tension pneumothorax

Electrolyte imbalance

Diabetes insipidus

SIADH

Others

Anemia

Hyperthermia

Hypercapnia

Hypoglycemia

NEUROSURGICAL CRITICAL CARE

683

when ICP is elevated and the cerebellar tonsils herniate through

the foramen magnum. This condition, known as tonsillar herni-

ation, can prove fatal because of the location of vital respiratory

and vasomotor centers in this area of the brain stem.

Alternatively, since cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP) is

inversely related to ICP,

∗

elevations in pressure may cause

impaired cerebral perfusion. If CPP is greatly reduced

(<40–50 mm Hg), cerebral ischemia or infarction can occur.

Therefore, maintenance of systemic blood pressure is of

paramount importance when ICP is elevated.

2. Secondary systemic insults—Of the various systemic

secondary insults, hypoxia and hypotension are the most

significant. Prospective clinical studies have demonstrated

that these two variables independently have a deleterious

influence on the outcome in severe head injury. Hypotension

alone is associated with a 150% increase in mortality rate. In

patients with significant head injuries, hypoxemia may be due

to upper airway obstruction, pneumothorax, hemothorax,

pulmonary edema, or hypoventilation. Whatever the cause,

hypoxemia must be corrected rapidly to avoid potential

damage to neural tissues. Hypotension reduces cerebral

perfusion, which promotes cerebral ischemia and infarc-

tion. This is particularly harmful in the face of elevated ICP.

In addition, impaired cerebral autoregulation can occur

after brain injury. With normal autoregulation, cerebral

blood flow remains constant despite fluctuation in mean

arterial pressure between 60 and 180 mm Hg (Figure 31–3).

Rapid arteriolar constriction or dilation occurs in response

to pressure changes. However, when this normal response is

Volume

ICP (mm Hg)

Figure 31–2. Intracranial pressure (ICP) remains normal with increased volume until the point of decompensation is

reached. Above this critical volume, ICP increases quickly.

Figure 31–3. Cerebral blood flow (CBF) remains normal over a wide range of cerebral perfusion pressures in nor-

mal patients. Under pathologic conditions, CBF varies directly with cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP).

CCP (mm Hg)

CBF (percent)

∗

Cranial perfusion pressure (CPP) = Mean arterial pressure (MAP) – Intracranial pressure (ICP)

CHAPTER 31

684

impaired, cerebral blood flow becomes directly related to

systemic arterial pressure. Thus, if hypotension occurs,

reduced tissue perfusion and ischemia may result. Elective

surgery for extracranial injuries should be delayed as long as

possible because of this issue. Surgery-related hypotensive

episodes can have correspondingly negative impact on brain

perfusion and ultimately the quality of overall outcome.

Other treatable or preventable systemic causes of secondary

brain injury include electrolyte disturbances, anemia, hypo-

glycemia, hyperthermia, coagulopathies, and seizures.

Clinical Features

A. Symptoms and Signs—Clinical examination remains

the best method for rapidly identifying neurologic deteriora-

tion. The Glasgow Coma Scale, which is based on eye open-

ing as well as verbal and motor responses, is used widely to

assess head injury patients (Table 31–2). Other important

components of the initial neurologic examination include

assessment of brain stem function, including level of con-

sciousness, respiratory pattern, pupillary size and reactivity,

as well as oculocephalic, oculovestibular, and gag reflexes. Eye

movements, extremity motor and sensory function, and lan-

guage and speech also should be evaluated. Following this

initial brief examination, a more thorough neurologic assess-

ment can be performed.

Transtentorial herniation, usually secondary to an

expanding supratentorial mass, produces a classic triad of

clinical signs: (1) depressed level of consciousness owing to

compression of the midbrain reticular activating system,

(2) anisocoria and loss of the pupillary light reflex owing to

ipsilateral third nerve compression, and (3) abnormal motor

findings from compression of the midbrain. In the early

stages of herniation, the ipsilateral third nerve is compressed;

however, if pressure on the brain stem increases, both pupils

may become dilated and unreactive. Contralateral hemipare-

sis owing to direct compression of the ipsilateral cerebral

peduncle is the most frequent abnormal motor response.

However, in about 25% of patients, hemiparesis may occur

on the same side as the mass lesion because the brain stem is

displaced away from the mass, compressing the opposite

cerebral peduncle against the free edge of the tentorium

(Kernohan’s notch phenomenon). The posterior cerebral

artery can be occluded during transtentorial herniation and

result in infarction of the occipital lobe it supplies.

Signs of tonsillar herniation include respiratory irregular-

ities, Cushing’s response (ie, elevated blood pressure associ-

ated with bradycardia), nuchal rigidity, and abnormal gag

and cough reflexes owing to medullary compression. During

early herniation, the patient’s level of consciousness may be

normal because the upper brain stem and reticular activating

system remain intact.

Neurologic deterioration in the ICU warrants immediate

and thorough evaluation in an effort to elucidate the cause.

Vital signs, serum electrolytes, O

2

saturation, and arterial

blood gas values should be determined if the deterioration is

global in nature. However, if the examination suggests a focal

lesion, an intracranial hematoma, elevated intracranial pres-

sure with a herniation syndrome, cerebral edema, or cerebral

ischemia is probably present. Studies validate that aggressive

medical management can reverse herniation and improve

outcome.

B. Imaging Studies—

1. CT scan—CT scanning is significantly more accurate than

conventional radiographs and has replaced them in the eval-

uation of head injuries. CT scanning can delineate parenchy-

mal hemorrhages and contusions, epidural and subdural

hematomas, cerebral edema, hydrocephalus, and cerebral

infarction. An intracranial lesion is said to exert a “mass

effect” on the brain when there is CT evidence of effacement

of the cerebral ventricles, subarachnoid cisterns, or cortical

sulci signifying redistribution of CSF. Further CT evidence of

a mass effect includes a shift of midline structures away from

the lesion and herniation of tissues. The outlet of the con-

tralateral ventricle can become “trapped” as a result of mid-

line shifting, and this can further increase ICP. Because MRI

is slower and generally not available emergently, especially in

intubated patients, it is not used commonly to assess acute

neurologic deteriorations. The availability of portable CT

scanners enables the diagnostic study to be performed with-

out transporting an unstable patient and risking harmful res-

piratory or cardiovascular events.

2. Cerebral angiography—Prior to the advent of CT

scanning, angiography was the primary diagnostic study for

evaluating head-injured patients because it detects the mass

effect from intracranial lesions. Currently, however, the main

role for angiography is the assessment of vascular disorders

Table 31–2. Glasgow Coma Scale.

Eye opening (E)

Spontaneous 4

To voice 3

To pain 2

None 1

Motor responses (M)

Obeys commands 6

Localizes pain 5

Withdraws 4

Abnormal flexion 3

Abnormal extension 2

None 1

Verbal responses (V)

Oriented 5

Confused 4

Inappropriate words 3

Incomprehensible sounds 2

None 1

TOTAL SCORE (3 to 15)

NEUROSURGICAL CRITICAL CARE

685

such as dissection or traumatic pseudoaneurysm of the

internal carotid or vertebral arteries and cerebral vasospasm.

Both MRI- and CT-based noncatheter angiography have sup-

planted invasive techniques for most emergency indications.

3. Transcranial Doppler ultrasonography—Transcranial

Doppler ultrasonography is a noninvasive technique that

measures blood flow velocity in the basal cerebral arteries.

It can be performed serially at the bedside in the ICU and

can reliably detect arterial narrowing owing to vasospasm,

which causes increased flow velocity. It also can aid in the

confirmation of absent blood flow owing to brain death.

C. Monitoring of Intracranial Pressure—Measurement of

ICP through an open catheter placed in the lateral ventricle

(ventriculostomy) is the standard with which all other meth-

ods of ICP measurement must be compared. Additionally,

CSF may be drained via the ventriculostomy to treat elevated

pressures, if present. Ventricular catheters may be placed in

the operating room during surgery or can be inserted at the

bedside in the emergency room or ICU. Because of the risk

of infection, patients with ventriculostomies should be given

prophylactic antibiotics with gram-positive coverage such as

cefazolin or vancomycin, and the catheters must be changed

periodically. Measurement of ICP also can be done using a

fiberoptic or strain-gauge device. These monitors are usually

more expensive, have a tendency to drift, and are unable to

drain CSF.

D. Lumbar Puncture—Lumbar puncture should not be per-

formed in the initial evaluation of head trauma patients

because of the risk of tonsillar herniation. The only role for

lumbar puncture is to examine CSF in patients who may

have meningitis. In such cases, ICP must be thought to lie

within the normal range prior to the procedure, or patients

should receive mannitol to induce diuresis prior to a small-

volume tap with a thin (eg, 22-gauge) spinal needle.

Treatment

A. Surgery—Patients who show neurologic deterioration

require rapid intervention to prevent irreversible tissue dam-

age. Cerebral contusions, intracranial hematomas, and for-

eign bodies may require emergent evacuation depending on

their size and location.

B. Reduction of Intracranial Pressure—Raised ICP should

be treated using the following measures:

1. Removal of CSF by ventricular drainage.

2. The use of mannitol prior to ICP monitoring should be

reserved for signs of transtentorial herniation or progres-

sive neurologic deterioration not attributable to systemic

extracranial explanations. Serum osmolarity should be

maintained below 320 mOsm/L to avoid renal failure, and

volume should be replaced with colloid agents or blood if

necessary to avoid hypotension or reduced cerebral per-

fusion. A Foley catheter is essential.

3. Hyperventilation results in cerebral vasoconstriction and

can help to reduce ICP for brief and specific periods. The

vasoconstrictive effects assist in the management of an

intracranial hypertensive crisis; however, the long-term

influence can produce permanent injury by reducing

blood flow below critical levels in an already injured

brain. Therefore, in the absence of high ICP, chronic

hyperventilation (Pa

CO

2

<25 mm Hg) should be avoided

in the first 24 hours after traumatic brain injury. In addi-

tion, the use of prophylactic hyperventilation (Pa

CO

2

<

35 mm Hg) during the first 24 hours should be limited

because it can compromise cerebral perfusion during a

time of reduced cerebral blood flow (CBF).

4. Head elevation should be maintained to promote cerebral

venous drainage. The head should be kept straight, and

tape from the endotracheal tube should not cross the

jugular area.

5. Sedation and neuromuscular paralysis are recommended

in intubated patients. Noxious stimuli may increase ICP,

which can be alleviated by sedation. Narcotics are useful

because they can be reversed rapidly. Neuromuscular

paralysis can reduce ICP in intubated patients by prevent-

ing increases in venous pressure associated with the Valsalva

maneuver during ventilatory support. Benzodiazepines and

propofol can be used as first-line agents for the sedation

of head-injured patients.

6. Anticonvulsant therapy (eg, IV keppra or phenytoin) can

be used to prevent or control seizure activity that

increases cerebral blood flow and subsequently ICP.

Available evidence does not indicate that the prevention

of early posttraumatic seizures improves outcome follow-

ing head injury, so these agents should be used with dis-

cretion. Bedside electroencephalography should be

obtained in patients with suspicious movements, pos-

tures, or eye movements and in those with unexplained

depression of consciousness. One week of prophylactic

anticonvulsant medication generally is sufficient in a

patient without evidence of seizure activity.

7. Fever increases ICP and should be prevented when possi-

ble. Chilled intravenous fluids or cooling blankets are

helpful for the management of refractory temperature

elevations.

8. Barbiturate (eg, pentobarbital) coma is useful if all other

medical therapies fail because it reduces ICP by decreas-

ing cerebral metabolism and therefore cerebral blood

flow. Care must be taken to prevent hypotension.

9. In selected patients in whom maximum medical therapy has

failed to reduce ICP, bony decompression or temporal lobec-

tomy can be performed surgically. Hemicraniectomy with

duraplasty can be performed in severe, refractory cases.

C. Electrolytes—Cerebral salt wasting is a recognized phe-

nomenon following brain injury and is caused by release of

cerebral natriuretic factors. It is defined as renal loss of

CHAPTER 31

686

sodium during intracranial disease leading to hyponatremia

and a decrease in extracellular fluid volume. Hyponatremia

produces increased brain swelling, and the volume depletion

that accompanies cerebral salt wasting must be treated

aggressively to avoid hypotension and reduced cerebral per-

fusion. Therefore, cerebral salt wasting should be recognized

promptly and treated with hypertonic saline solutions.

Traumatic brain injury also can result in a number of

other electrolyte disturbances requiring treatment, including

hypomagnesemia, hypophosphotemia, and hypokalemia.

Becker DP, Gudeman SK (eds): Textbook of Head Injury.

Philadelphia: Saunders, 1989.

Chesnut RM, Marshall LF: Treatment of abnormal intracranial

pressure. Neurosurg Clin North Am 1991;2:267–84.

Cooper PR: Delayed brain injury: Secondary insults. In Becker DP,

Povlishock JT (eds), Central Nervous System Trauma Status

Report—1985. Prepared for the National Institute of

Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke.

Washington: National Institutes of Health, 1986.

Guidelines for the Management of Severe Head Injury, 2d ed.

Washington: Brain Tumor Foundation, 2000.

Marshall LF, Smith RW, Shapiro HM: The outcome with aggressive

treatment in severe head injuries. J Neurosurg 1979;50:20–5.

[PMID: 758374]

Seelig JM et al: Traumatic acute subdural hematoma: Major mor-

tality reduction in comatose patients treated under four hours.

N Engl J Med 1981;304:1511–8. [PMID: 7231489]

Temkin NR et al: A randomized double-blind study of phenytoin

for prevention of post-traumatic seizures. N Engl J Med

1990;323:497–502. [PMID: 2115976]

Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Headache.

Nausea and vomiting.

Photophobia.

Nuchal rigidity.

Depressed level of consciousness.

Cranial nerve palsies, motor abnormalities.

General Considerations

Rupture of an intracranial aneurysm is a devastating event

because roughly half of these patients die. Of the remainder,

almost half are left with significant neurologic deficits as a

result of their initial hemorrhage or owing to delayed com-

plications such as rebleeding, vasospasm, or hydrocephalus.

In order to optimize outcome following subarachnoid hem-

orrhage, successful surgical or radiologic intervention and

meticulous ICU care are required.

Intracranial aneurysms typically occur at bifurcation sites

of major arteries at the base of the brain and usually point in

the direction of blood flow. It is believed that a defect in the

medial elastic lamina is present that predisposes to aneurysm

formation. Aneurysms are associated with a variety of condi-

tions, including hypertension, polycystic kidney disease,

coarctation of the aorta, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, pseudoxan-

thoma elasticum, and cerebral arteriovenous malformations.

Approximately 85% are located in the anterior circulation,

with the most common sites being the junction of the anterior

cerebral and anterior communicating arteries, the junction of

the internal carotid and posterior communicating arteries, the

bifurcation or trifurcation of the middle cerebral artery, and

the bifurcation of the internal carotid artery. Fifteen percent of

aneurysms lie within the posterior circulation; the basilar

artery apex is the most common site. Multiple aneurysms can

be identified in 15–20% of patients. Since the cerebral arteries

course within the subarachnoid space, rupture typically pro-

duces subarachnoid hemorrhage. However, intraparenchymal

and intraventricular bleeding may occur depending on the

location of the aneurysm and the extent of bleeding.

The three major complications following aneurysmal sub-

arachnoid hemorrhage are rebleeding, vasospasm, and hydro-

cephalus. Rebleeding from a ruptured intracranial aneurysm

occurs in 20% of patients during the first 2 weeks after the

initial hemorrhage if the aneurysm is untreated. The highest

risk is in the first 24 hours, and occlusive treatment with sur-

gery or interventional embolization is required. Cerebral

vasospasm is a common delayed complication of subarach-

noid hemorrhage and is related to the amount of blood

located within the subarachnoid space. Vasospasm typically

occurs between 3 and 14 days postbleed. Arterial narrowing is

thought to result from degradation of subarachnoid blood,

which produces breakdown products that cause smooth mus-

cle constriction. If this smooth muscle constriction is pro-

longed, morphologic alterations such as fibrosis can occur in

the vessel wall, further enhancing arterial narrowing.

Communicating hydrocephalus is another complication that

can occur after subarachnoid hemorrhage and is secondary to

blockage of CSF reabsorption by platelets, erythrocytes, and

their breakdown products. Hydrocephalus may present in an

acute, subacute, or delayed fashion.

In addition to the previously described neurologic com-

plications, several systemic medical disorders can occur fol-

lowing subarachnoid hemorrhage. Cardiac arrhythmias and

myocardial ischemia are observed often. Respiratory compli-

cations such as pulmonary edema, acute respiratory distress

syndrome (ARDS), and pneumonia are common. Other dis-

orders such as anemia, GI bleeding, deep vein thrombosis,

and hyponatremia occur with varying frequency.

Clinical Features

A. Symptoms and Signs—Subarachnoid hemorrhage is

described most often as the sudden onset of the worst

headache of the patient’s life. Other symptoms such as nausea