Bongard Frederic , Darryl Sue. Diagnosis and Treatment Critical Care

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

AUTHORS

ix

Bruce L. Miller, MD

Clausen Distinguished Professor of Neurology, University

of California, San Francisco; Memory and Aging Center,

San Francisco, California

bruce@email.his.ucsf.edu

Critical Care of Neurologic Disease

David W. Mozingo, MD

Professor of Surgery and Anesthesiology, University of

Florida; Chief, Division of Acute Care Surgery, Director,

Shands Burn Center, Gainesville, Florida

mozindw@surgery.ufl.edu

Burns

Kenneth A. Narahara, MD

Professor of Medicine, David Geffen School of Medicine,

University of California, Los Angeles, School of

Medicine; Assistant Chair for Clinical Affairs,

Department of Medicine, Director, Coronary Care,

Division of Cardiology, Harbor-UCLA Medical Center,

Torrance, California

knarahara@labiomed.org

Coronary Heart Disease

Gideon P. Naudé, MD

Chairman, Department of Surgery, Tuolumne General

Hospital, Sonora, California

gpnaude@aol.com

Gastrointestinal Failure in the ICU

Dean C. Norman, MD

Chief of Staff, Veterans Administration Greater Los Angeles

Healthcare System; Professor of Medicine, University of

Southern California, Los Angeles, California

Dean.Norman@med.va.gov

Care of the Elderly Patient

Basil A. Pruitt, Jr., MD, FACS, FCCM

Clinical Professor, Department of Surgery, University of

Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio; Consultant,

U.S. Army Institute of Surgical Research, San Antonio,

Texas

pruitt@uthscsa.edu

Burns

Steven S. Raman, MD

Associate Professor, Department of Radiology, David Geffen

School of Medicine, University of California,

Los Angeles, California

SRaman@mednet.ucla.edu

Imaging Procedures

Sofiya Reicher, MD

Assistant Clinical Professor of Medicine, David Geffen

School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles,

California

sreicher@sbcglobal.net

Gastrointestinal Bleeding

William P. Schecter, MD

Professor of Clinical Surgery and Vice Chair, University

of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, California;

Chief of Surgery, San Francisco General Hospital, San

Francisco, California

bschect@sfghsurg.ucsf.edu

Care of Patients with Environmental Injuries

Paul A. Selecky, MD

Clinical Professor of Medicine, David Geffen School of

Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles,

California; Medical Director, Pulmonary Department,

Hoag Hospital, Newport Beach, California

pselecky@hoaghospital.org

Ethical, Legal, & Palliative/End-of-Life Care Considerations

Shelley Shapiro, MD, PhD

Clinical Professor of Medicine, David Geffen School of

Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles,

California

sshapiro@ucla.edu

Cardiac Problems in Critical Care

Elizabeth D. Simmons, MD

Partner, Southern California Permanente Medical Group,

Los Angeles, California

Elizabeth.D.Simmons@kp.org

Transfusion Therapy; Bleeding & Hemostasis; Antithrombotic

Therapy

Michael J. Stamos, MD

Professor of Surgery and Chief, Division of Colon and Rectal

Surgery, University of California, Irvine, Orange, California

mstamos@uci.edu

Acute Abdomen

Samuel J. Stratton, MD, MPH

Professor of Emergency Medicine, University of California

Irvine, Orange, California

sstratton@att.net

Transport

AUTHORS

x

Darryl Y. Sue, MD

Professor of Clinical Medicine, David Geffen School

of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles,

California; Director, Medical-Respiratory Intensive Care

Unit, Division of Respiratory and Critical Care

Physiology and Medicine, Associate Chair

and Program Director, Department of Medicine,

Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, Torrance, California

dsue@ucla.edu

Philosophy & Principles of Critical Care; Fluids, Electrolytes,

& Acid-Base; Pharmacotherapy; Intensive Care

Monitoring; Respiratory Failure; Critical Care

of the Oncology Patient; Pulmonary Disease; HIV

Infection in the Critically Ill Patient

John A. Tayek, MD

Associate Professor of Medicine-in-Residence, David Geffen

School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles,

Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, Torrance, California

jtayek@ladhs.org

Nutrition

Timothy L. Van Natta, MD

Associate Professor of Surgery, David Geffen School of

Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles,

Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, Torrance, California

timothy.vannatta@gmail.com

Surgical Infections

Hernan I. Vargas, MD

Associate Professor of Surgery, David Geffen School

of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles,

California; Chief, Division of Surgical Oncology, Harbor-

UCLA Medical Center, Torrance, California

hvargas@ucla.edu

Hepatobiliary Disease

Edward D. Verrier, MD

William K. Edmark Professor of Cardiovascular Surgery,

Vice Chairman, Department of Surgery, University

of Washington, Seattle, Washington; Chief, Division

of Cardiothoracic Surgery, University of Washington,

Seattle, Washington

edver@u.washington.edu

Cardiothoracic Surgery

Janine R. E. Vintch, MD

Associate Clinical Professor of Medicine, David Geffen

School of Medicine, University of California, Los

Angeles, Divisions of General Internal Medicine and

Respiratory and Critical Care Physiology and Medicine,

Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, Torrance, California

jvintch@ladhs.org

Respiratory Failure; Pulmonary Disease

Kenneth Waxman, MD

Director of Surgical Education, Santa Barbara Cottage

Hospital, Santa Barbara, California

kwaxman@sbch.org

Intensive Care Monitoring

Mallory D. Witt, MD

Professor of Medicine, David Geffen School of Medicine,

University of California, Los Angeles, California;

Associate Chief, Division of HIV Medicine, Harbor-

UCLA Medical Center, Torrance, California

mwitt@labiomed.org

Infections in the Critically Ill; HIV Infection in the

Critically Ill Patient

Nam C. Yu, MD

Resident Physician, Department of Radiology, David Geffen

School of Medicine, University of California,

Los Angeles, California

nyu@mednet.ucla.edu

Imaging Procedures

Kory J. Zipperstein, MD

Chief, Department of Dermatology, Kaiser-Permanente

Medical Center, San Francisco, California

Kory.Zipperstein@kp.org

Dermatologic Problems in the Intensive Care Unit

xi

Preface

The third edition of Current Diagnosis & Treatment: Critical Care is designed to serve as a single-source reference for the adult

critical care practitioner. The diversity of illnesses encountered in the critical care population necessitates a well-rounded and

thorough knowledge of the manifestations and mechanisms of disease. In addition, unique to the discipline of critical care is

the integration of an extensive body of medical knowledge that crosses traditional specialty boundaries. This approach is

readily apparent to intensivists, whose primary background may be in internal medicine or one of its subspecialties, surgery,

or anesthesiology. Thus a central feature of this book is a unified and integrated approach to the problems encountered in

critical care practice. Like other books with the Lange imprint, this book emphasizes recall of major diagnostic features,

concise descriptions of disease processes, and practical management strategies based on often recently acquired evidence.

INTENDED AUDIENCE

Planned by two internists and a surgeon to meet the need for a concise but thorough source of information, Current Diagnosis

& Treatment: Critical Care is intended to facilitate both teaching and practice of critical care. Students will find its consid-

eration of basic science and clinical application useful during clerkships on medicine, surgery, and intensive care unit electives.

House officers will appreciate its descriptions of disease processes and organized approach to diagnosis and treatment. Fellows

and those preparing for critical care specialty examinations will find those sections outside their primary disciplines particu-

larly useful. Clinicians will recognize this succinct reference on critical care as a valuable asset in their daily practice.

Because this book is intended as a reference on various aspects of adult critical care, it does not contain chapters on

pediatric or neonatal critical care. These areas are highly specialized and require entire monographs of their own. Further, we

have not included detailed information on performing bedside procedures such as central venous catheterization or arterial line

insertion. Well-illustrated pocket manuals are available for readers who require basic technical information. Finally, we have

chosen not to include a chapter on nursing or administrative topics, details of which can be found in other works.

ORGANIZATION

Current Diagnosis & Treatment: Critical Care is conceptually organized into three major sections: (1) fundamentals of crit-

ical care applicable to all patients, (2) topics related primarily to critical care of patients with medical diseases, and (3) essentials of

care for patients requiring care for surgical problems. Early chapters provide information about the general physiology and

pathophysiology of critical illness. The later chapters discuss pathophysiology using an organ system– or disease-specific

approach. Where appropriate, we have placed the medical and surgical chapters in succession to facilitate access to information.

OUTSTANDING FEATURES

Concise, readable format, providing efficient use in a variety of clinical and academic settings

Edited by both surgical and medical intensivists, with contributors from multiple subspecialties

Illustrations chosen to clarify basic and clinical concepts

Careful evaluation of new diagnostic procedures and their usefulness in specific diagnostic problems

Updated information on the management of severe sepsis and septic shock, including hydrocortisone therapy

New information on the serotonin syndrome

Carefully selected key references in Index Medicus format, providing all information necessary to allow electronic retrieval

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The editors wish to thank Robert Pancotti and Ruth W. Weinberg at McGraw-Hill for unceasing efforts to motivate us and keep

us on track. We are also very grateful to our families for their support.

Frederic S. Bongard, MD

Darryl Y. Sue, MD

Janine R. E. Vintch, MD

July 2008

Copyright © 2008 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. Click here for terms of use.

This page intentionally left blank

1

1

Philosophy & Principles

of Critical Care

Darryl Y. Sue, MD

Frederic S. Bongard, MD

Critical care is unique among the specialties of medicine.

While other specialties narrow the focus of interest to a sin-

gle body system or a particular therapy, critical care is

directed toward patients with a wide spectrum of illnesses.

These have the common denominators of marked exacerba-

tion of an existing disease, severe acute new problems, or

severe complications from disease or treatment. The range

of illnesses seen in a critically ill population necessitates

well-rounded and thorough knowledge of the manifesta-

tions and mechanisms of disease. Assessing the severity of

the patient’s problem demands a simultaneously global and

focused approach, depends on accumulation of accurate

data, and requires integration of these data. Although prac-

titioners of critical care medicine—sometimes called

intensivists—are often specialists in pulmonary medicine,

cardiology, nephrology, anesthesiology, surgery, or critical

care, the ability to provide critical care depends on the basic

principles of internal medicine and surgery. Critical care

might be considered not so much a specialty as a “philoso-

phy” of patient care.

The most important development in recent years has

been an explosion of evidence-based critical care medicine

studies. For the first time, we have evidence for many of the

things that we do for patients in the ICU. Examples include

low tidal volume strategies for acute respiratory distress

syndrome, tight glycemic control, prevention of ventilator-

associated pneumonia, and use of corticosteroids in septic

shock (Table 1–1). The resulting improvement in outcome

is gratifying, but even more surprising is how often evi-

dence contradicts long-held beliefs and assumptions.

Probably the best example is recent studies that conclude

that the routine use of pulmonary artery catheters in ICU

patients adds little or nothing to management. Much more

needs to be studied, of course, to address other unresolved

issues and controversies.

Do intensivists make a difference in patient outcome?

Several studies have shown that management of patients by

full-time intensivists does improve patient survival. In fact,

several national organizations recommend strongly that full-

time intensivists provide patient care in all ICUs. It can be

argued, however, that local physician staffing practices;

interactions among primary care clinicians, subspecial-

ists, and intensivists; patient factors; and nursing and

ancillary support play large roles in determining out-

comes. In addition, recent studies show that patients do

better if an ICU uses protocols and guidelines for routine

care, controls nosocomial infections, and provides feed-

back to practitioners.

The general principles of critical care are presented in this

chapter, as well as some guidelines for those who are respon-

sible for leadership of ICUs.

GENERAL PRINCIPLES OF CRITICAL CARE

Early Identification of Problems

Because critically ill patients are at high risk for developing

complications, the ICU practitioner must remain alert to

early manifestations of organ system dysfunction, complica-

tions of therapy, potential drug interactions, and other pre-

monitory data (Table 1–2). Patients with life-threatening

illness in the ICU commonly develop failure of other

organs because of hemodynamic compromise, side effects

of therapy, and decreased organ function reserve, espe-

cially those who are elderly or chronically debilitated. For

example, positive-pressure mechanical ventilation is asso-

ciated with decreased perfusion of organs. Many valuable

drugs are nephro- or hepatotoxic, especially in the face of

preexisting renal or hepatic insufficiency. Older patients

are more prone to drug toxicity, and polypharmacy pres-

ents a higher likelihood of adverse drug interactions. Just as

patients with acute coronary syndrome and stroke benefit

from early intervention, an exciting finding is the evidence

that the first 6 hours of management of septic shock are very

important.

Copyright © 2008 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. Click here for terms of use.

CHAPTER 1

2

Identifying and acting on new problems and complica-

tions in the ICU demands frequent and regular review of all

information available, including changes in symptoms, phys-

ical findings, and laboratory data and information from mon-

itors. In some facilities, early identification and treatment are

provided by rapid-response teams. Once notified that a patient

outside the ICU may be deteriorating, the team is mobilized

to provide a mini-ICU environment in which critical care can

be delivered early, even before the patient is actually

transferred.

Effective Use of the Problem-Oriented

Medical Record

The special importance of finding, tracking, and being aware

of ICU issues demands an effective problem-oriented med-

ical record. In order to define and follow problems effec-

tively, each problem should be reviewed regularly and

characterized at its current state of understanding. For exam-

ple, if the general problem of “renal failure” subsequently has

been determined to be due to aminoglycoside toxicity, it

should be described in that way in an updated problem list.

However, even the satisfaction of identifying a cause of the

renal failure may be short-lived. The same patient subse-

quently may develop other related or unrelated renal prob-

lems, thereby forcing reassessment.

In our opinion, ICU problems must not be restricted to

“diagnoses.” We list intravascular catheters and the date they

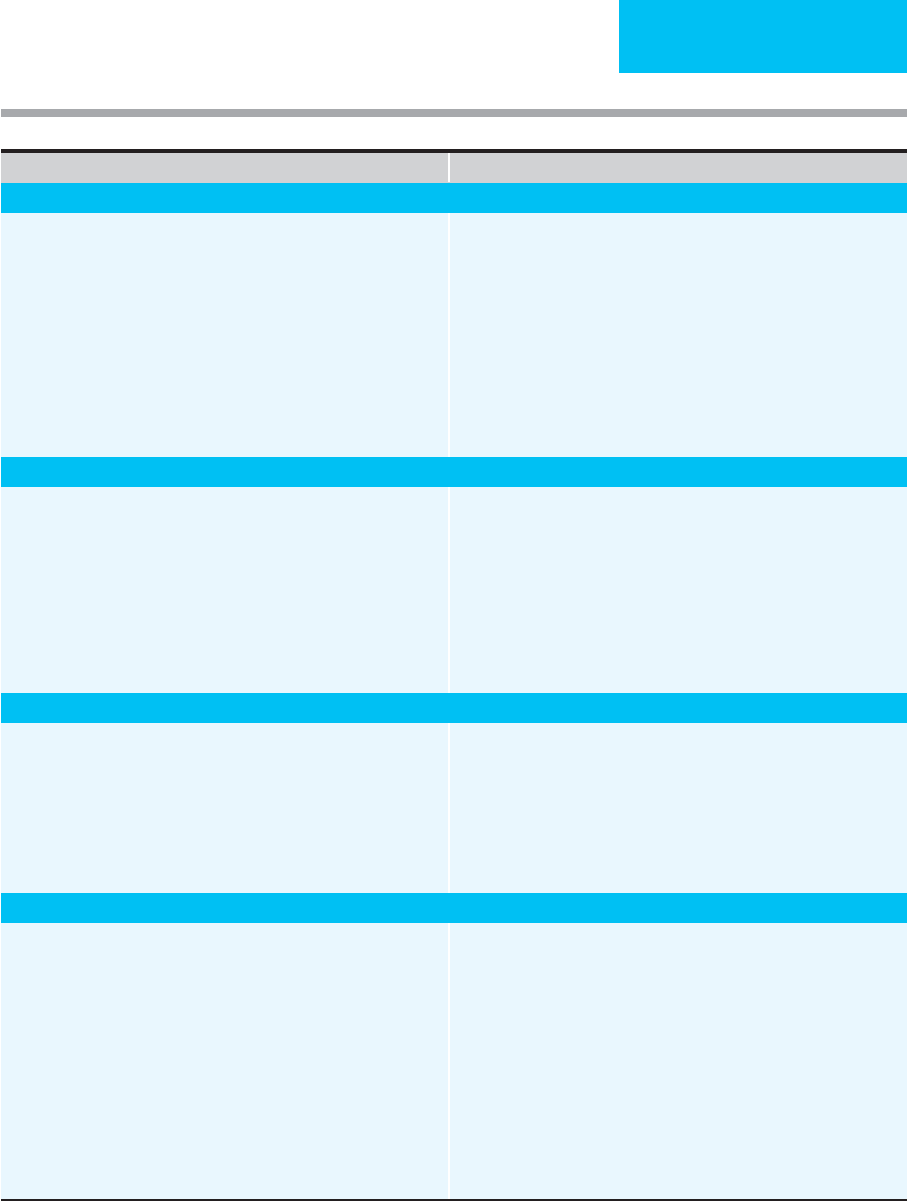

Table 1–1. Recent developments in evidence-based

critical care medicine.

Table 1–2. Recommendations for routine patient care in

the ICU.

• Assess current status, interval history, and examination.

• Review vital signs for interval period (since last review).

• Review medication record, including continuous infusions:

Duration and dose

Changes in dose or frequency based on changes in renal, hepatic,

or other pharmacokinetic function

Changes in route of administration

Potential drug interactions

• Correlate changes in vital signs with medication administration and

other changes by use of chronologic charting.

• Integrate nursing, respiratory therapists, patient, family, and other

observations.

• Review, if indicated:

Respiratory therapy flow chart

Hemodynamics records

Laboratory flowsheets

Other continuous monitoring

• Review all problems, including adding, updating, consolidating, or

removing problems as indicated.

• Periodically, review supportive care:

Intravenous fluids

Nutritional status and support

Prophylactic treatment and support

Duration of catheters and other invasive devices

• Review and contrast risks and benefits of intensive care.

• Corticosteroids improve outcome in exacerbations of chronic obstruc-

tive respiratory disease (COPD).

• A low tidal volume strategy decreases mortality in acute respiratory

distress syndrome (ARDS).

• A lower hemoglobin decision point for transfusion of red blood cells

in many ICU patients results in similar outcome and greatly reduced

use of blood products.

• Tight glycemic control in postoperative surgical patients, most of

whom did not have diabetes, resulted in less mortality and fewer

complications.

• Elevating the head of the bed to 30–45 degrees in ICU patients

reduces the incidence of nosocomial pneumonia.

• Daily withholding of sedation in the ICU decreases the number of

ICU days and results in fewer evaluations for altered level of

consciousness.

• Daily spontaneous breathing trials lead to faster weaning from

mechanical ventilation and shorter duration of ICU stay.

• Low-dose (physiologic) vasopressin may reduce the need for pres-

sors in septic shock.

• Fluid resuscitation using colloid-containing solutions is not more ben-

eficial than crystalloid fluids.

• Low-dose dopamine does not improve renal function or diuresis and

does not protect against renal dysfunction.

• Acetylcysteine or sodium bicarbonate protect against radiocontrast

material–induced acute renal failure.

• Patients with bleeding esophageal varices have a higher rebleeding

risk if they have infection, especially spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.

• Noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation decreases the need for

intubation in patients with COPD exacerbation.

• Noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation is associated with fewer

respiratory infections than conventional ventilation.

• Early goal-directed therapy for sepsis (specific targets for central

venous pressure, hemoglobin, and central venous oxygen content

during the first 6 hours of care) decreases mortality.

PHILOSOPHY & PRINCIPLES OF CRITICAL CARE

3

were inserted on the problem list. This helps us to remember

to consider the catheter as a site of infection if the patient

has a fever. Other “nondiagnoses” on our problem list

include nutritional support, prevention of deep vein

thrombosis and decubitus ulcers, drug allergies, patient

positioning, and prevention of stress ulcers. It may be use-

ful to include nonmedical issues as well so that they can be

discussed routinely. Examples are psychosocial difficul-

ties, unresolved end-of-life decisions, and other questions

about patient comfort. Finally, we share the patient’s

problem-oriented record with nonphysicians caring for the

patient, a process that enhances communication, simplifies

interactions between staff members, and furthers the goals

of patient care.

Monitoring & Data Display

A tremendous amount of patient data is acquired in the

ICU. Although ICU monitoring is often thought of as

electrocardiography, blood pressure measurements, and

pulse oximetry, ICU data include serial plasma glucose

and electrolyte determinations, arterial blood gas deter-

minations, documentation of ventilator settings and

parameters, and body temperature determinations. Taking

a daily weight is invaluable in determining the net fluid

balance of a patient.

Flowcharts of laboratory data and mechanical ventilator

activity, 24-hour vital signs, graphs of hemodynamic data, and

lists of medications are indispensable tools for good patient

care, and efforts should be made to find the most effective and

efficient ways of displaying such information in the ICU.

Methods that integrate the records of physicians, nurses, respi-

ratory therapists, and others are particularly useful.

Computer-assisted data collection and display systems

are found increasingly in ICUs. Some of these systems

import data directly from bedside monitors, mechanical

ventilators, intravenous infusion pumps, fluid collection

devices, clinical laboratory instruments, and other devices.

ICU practitioners may enter progress notes, medications

administered, and patient observations. Advantages of these

systems include decreased time for data collection and the

ability to display data in a variety of formats, including flow-

charts, graphs, and problem-oriented records. Such data can

be sent to remote sites for consultation, if necessary.

Computerized access to data facilitates research and quality

assurance studies, including the use of a variety of prognos-

tic indicators, severity scores, and ICU decision-making

tools. Computerized information systems have the potential

for improving patient care in the ICU, and their benefit to

patient outcome continues to be studied.

The next step is to integrate ICU data with treatment,

directly and indirectly. One excellent example is glycemic

control so that up-to-date blood glucose measurements

will be linked closely to insulin protocols—at first with

the nurse and physician “in the loop” but potentially with

real-time feedback and automated adjustment of insulin

infusions.

Supportive & Preventive Care

Many studies have pointed out the high prevalence of gas-

trointestinal hemorrhage, deep venous thrombosis, decu-

bitus ulcers, inadequate nutritional support, nosocomial

and ventilator-associated pneumonias, urinary tract infec-

tions, psychological problems, sleep disorders, and other

untoward effects of critical care. Efforts have been made to

prevent, treat, or otherwise identify the risks for these

complications. As outlined in subsequent chapters, effec-

tive prevention is available for some of these risks (Table 1–3);

for other complications, early identification and aggres-

sive intervention may be of value. For example, aggressive

nutritional support for critically ill patients is often indi-

cated both because of the presence of chronic illness and

malnutrition and because of the rapid depletion of

nutritional reserves in the presence of severe illness.

Nutritional support, prevention of upper gastrointestinal

bleeding and deep venous thrombosis, skin care, and other

supportive therapy should be included on the ICU

patient’s problem list. To these, we have added glycemic

control because of recent data indicating reduced morbid-

ity and mortality in medical and surgical patients whose

plasma glucose concentration is maintained in a relatively

narrow range.

Because of expense and questions of effectiveness and

safety, studies of preventive treatment of ICU patients con-

tinue. For example, a multicenter study reported that clini-

cally important gastrointestinal bleeding in critically ill

patients was seen most often only in those with respiratory

failure or coagulopathy (3.7% for one or both factors).

Otherwise, the risk for significant bleeding was only 0.1%.

The authors suggested that prophylaxis against stress ulcer

could be withheld safely from critically ill patients unless

they had one of these two risk factors. On the other hand,

about half the patients in this study were post–cardiac sur-

gery patients, and the majority of patients in many ICUs have

one of the identified risk factors. Thus there may not be suf-

ficient compelling evidence to discontinue the practice of

providing routine prophylaxis for gastrointestinal bleeding

in all ICU patients.

Other routine practices have been challenged. For exam-

ple, several studies show that routine transfusion of red

blood cells in ICU patients who reached an arbitrary hemo-

globin level did not change outcome when compared with

allowing hemoglobin to fall to a lower value. Further studies

are needed to define the role of other preventive strategies.

Important questions include differences in the need for

glycemic control, critical differences in the intensity and type

of therapy needed to prevent thrombosis, the optimal hemo-

globin for patients with myocardial infarction, and the bene-

fit of tailored nutritional support.

CHAPTER 1

4

(

continued

)

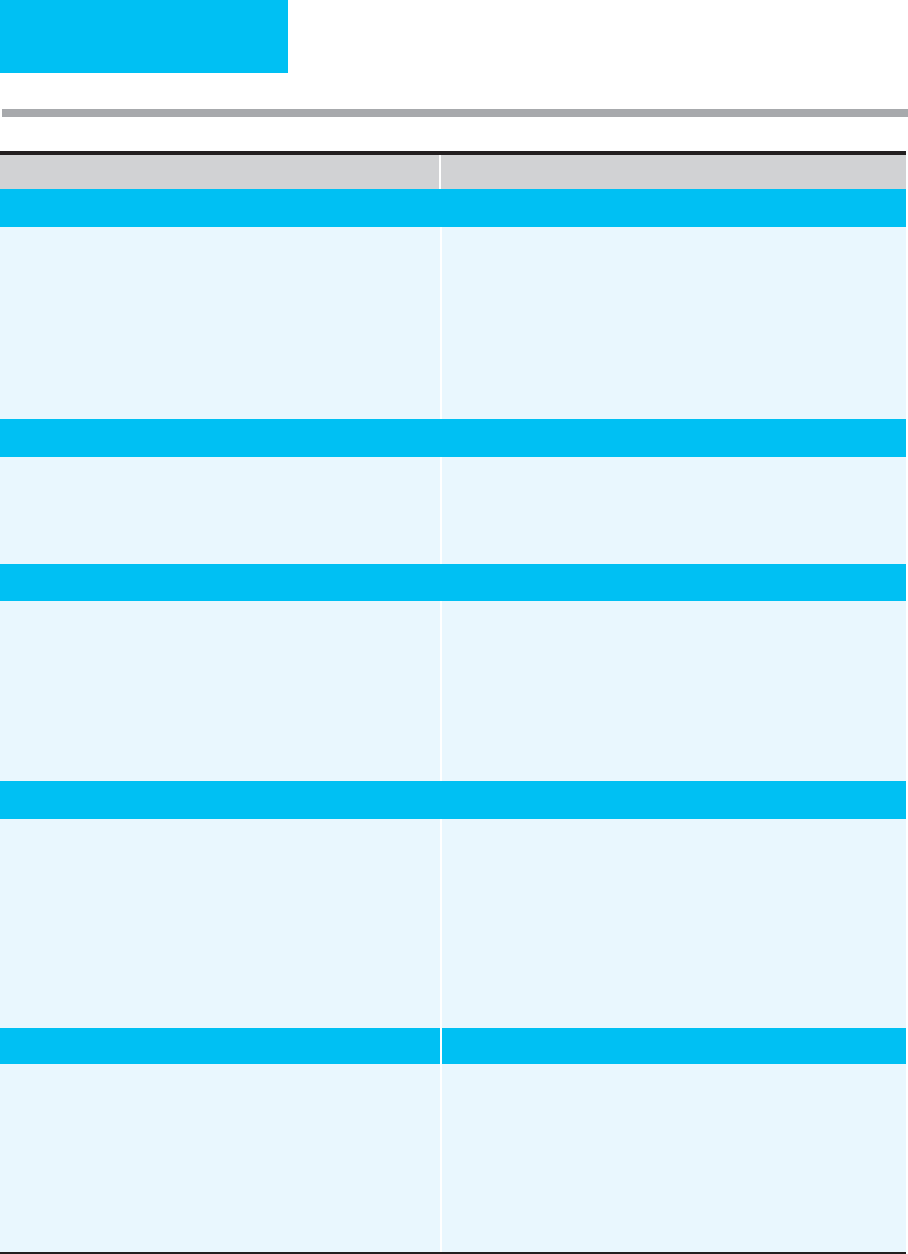

Things To Think About Reminders

General ICU Care

1. Nosocomial infections, especially line- and catheter-related.

2. Stress gastritis.

3. Deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism.

4. Exacerbation of malnourished state.

5. Decubitus ulcers.

6. Psychosocial needs and adjustments.

7. Toxicity of drugs (renal, pulmonary, hepatic, CNS).

8. Development of antibiotic-resistant organisms.

9. Complications of diagnostic tests.

10. Correct placement of catheters and tubes.

11. Need for vitamins (thiamine, C, K).

12. Tuberculosis, pericardial disease, adrenal insufficiency, fungal sepsis,

rule out myocardial infarction, pneumothorax, volume overload or

volume depletion, decreased renal function with normal serum crea-

tinine, errors in drug administration or charting, pulmonary vascular

disease, HIV-related disease.

1. Discontinue infected or possibly infected lines.

2. Need for H2 blockers, antacids, or sucralfate.

3. Provide enteral or parenteral nutrition.

4. Change antibiotics?

5. Chest x-ray for line placement.

6. Review known drug allergies (including contrast agents).

7. Check for drug dosage adjustments (new liver failure or renal failure).

8. Need for deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis?

9. Pain medication and sedation.

10. Weigh patient.

11. Give medications orally, if possible.

12. Does patient really need an arterial catheter?

13. Give thiamine early.

Nurition

1. Set goals for appropriate nutrition support.

2. Avoid or minimize catabolic state.

3. Acquired vitamin K deficiency while in ICU.

4. Avoidance of excessive fluid intake.

5. Diarrhea (lactose intolerance, low serum protein, hyperosmolarity,

drug-induced, infectious).

6. Minimize and anticipate hyperglycemia during parenteral nutritional

support.

7. Adjustment of rate or formula in patients with renal failure or liver

failure.

8. Early complications of refeeding.

9. Acute vitamin insufficiency.

1. Calculate estimated basic caloric and protein needs. Use 30 kcal/kg

and 1.5 g protein/kg for starting amount.

2. Regular food preferred over enteral feeding; enteral feeding preferred

over parenteral in most patients.

3. Increased caloric and protein requirements if febrile, infected, agitated,

any inflammatory process ongoing, some drugs.

4. Adjust protein if renal or liver failure is present. Adjust again if dialysis

is used.

5. Measure serum albumin as primary marker of nutritional status.

6. Give vitamin K, especially if malnourished and receiving antibiotics.

7. Consider volume restriction formulas (both enteral and parenteral).

8. Give phosphate early during refeeding.

9. Control hyperglycemia (glucose <110–120 mg/dL).

Acute Renal Failure

1. Volume depletion, hypoperfusion, low cardiac output, shock.

2. Nephrotoxic drugs.

3. Obstruction of urine outflow.

4. Interstitial nephritis.

5. Manifestation of systemic disease, multiorgan system failure.

6. Degree of preexisting chronic renal failure.

1. Measure urine Na

+

, Cl

–

, creatinine, and osmolality.

2. Volume challenge, if indicated.

3. Discontinue nephrotoxic drugs if possible.

4. Adjust all renally excreted drugs.

5. Renal medicine consultation for dialysis, other management.

6. Renal ultrasound if indicated for obstruction.

7. Check catheter and replace if indicated.

8. Stop potassium supplementation if necessary.

9. Adjust diet (Na

+

, protein, etc.).

10. If dialytic therapy is begun, adjust drugs if necessary.

11. Weigh patient daily.

Table 1–3. Things to think about and reminders for ICU patient care.

PHILOSOPHY & PRINCIPLES OF CRITICAL CARE

5

Things To Think About Reminders

Acute Respiratory Failure, COPD

1. Adequacy of oxygenation.

2. Exacerbation due to infection, malnutrition, congestive heart failure.

3. Airway secretions.

4. Other medical problems (coexisting heart failure).

5. Hypotension and low cardiac output response to positive-pressure

ventilation.

6. Hyponatremia, SIADH.

7. Severe pulmonary hypertension.

8. Sleep deprivation.

9. Coexisting metabolic alkalosis.

1. Should patient be intubated or mechanically ventilated?

Noninvasive mechanical ventilation?

2. Bronchodilators.

3. Consider corticosteroids, ipratropium.

4. Sufficient supplemental oxygen.

5. Antibiotic coverage for common bacterial causes of exacerbations.

Evaluate for pneumonia as well as acute bronchitis.

6. Early nutrition support.

7. Check theophylline level, if indicated.

8. Ventilator management: low tidal volume, long expiratory time, high

inspiratory flow, watch for auto-PEEP.

9. Think about weaning early.

Acute Respiratory Failure, ARDS

1. Sepsis as cause, from pulmonary or nonpulmonary site (abdominal,

urinary).

2. Possible aspiration of gastric contents.

3. Fluid overload or contribution form congestive heart failure.

4. Anticipate potential multiorgan system failure.

5. Assess the risks of oxygen toxicity versus complications of PEEP.

6. Consider the complications of high airway pressure or large tidal vol-

ume in selection of type of mechanical ventilatory support.

7. Low serum albumin (contribution from hypo-oncotic pulmonary

edema).

1. Early therapeutic goal of Fi0

2

<0.50 and lowest PEEP (<5–10 cm H

2

O),

resulting in acceptable O

2

delivery.

2. Directed (if possible) or broad-spectrum antibiotics.

3. Evaluate for soft tissue or intra-abdominal infection source.

4. Diuretics, if necessary. Assess need for fluid intake to support O

2

delivery.

5. Evaluate intake and output daily; weigh patient daily.

6. Use low tidal volume, ≤6 ml/kg to keep plateau pressure

<30 cm H

2

O.

7. Follow renal function, electrolytes, liver function, mental status to

assess organ system function.

Asthma

1. Airway inflammation is the primary cause of status asthmaticus.

2. Auto-PEEP or hyperinflation dominates gas exchange when using

mechanical ventilation.

3. Potentially increased complication rate of mechanical ventilation.

1 High-dose corticosteroids are primary treatment.

2. Aggressive inhaled aerosolized β

2

agonists (hourly, if needed).

3. Early intubation if necessary.

4. Adequate oxygen to inhibit respiratory drive.

5. Use low tidal volume, high inspiratory flow, low respiratory frequency

with mechanical ventilation to avoid barotrauma and auto-PEEP.

6. May need to sedate or paralyze to reduce hyperinflation.

7. Measure peak flow or FEV, as a guide to therapeutic response.

Diabetic Ketoacidosis

1. Evaluate degree of volume depletion and relationship of water to

solute balance (hyperosmolar component).

2. Avoid excessive volume replacement.

3. Look for a trigger for diabetic ketoacidosis (infection, poor compliance,

mucormycosis, other).

4. Avoid hypoglycemia during correction phase.

5. Identify features of hyperosmolar complications.

6. Calculate water and volume deficits.

7. Evaluate presence of coexisting acid-base disturbances (lactic acidosis,

metabolic alkalosis).

8. Avoid hypokalemia and hypophosphatemia during correction phase.

1. Give adequate insulin to lower glucose at appropriate rate (increase

aggressively if no response). Use continuous insulin infusion.

2. Give adequate volume replacement (normal saline) and water replace-

ment, if needed (half normal saline, glucose in water).

3. Follow glucose and electrolytes frequently.

4. Consider stopping insulin infusion when glucose is about 250 mg/dL

and HCO

3

–

is >18 meq/L.

5. Avoid hypoglycemia; if you continue insulin drip with glucose <250mg/dL,

then give D

5

W. If glucose continues to fall, lower insulin drip rate.

6. Monitor serum potassium, phosphorus.

7. Calculate water deficit, if any.

8. Urine osmolality, glucose, etc.

9. Check sinuses, nose, mouth, soft tissue, urine, chest x-ray, abdomen for

infection.

(

continued

)

Table 1–3. Things to think about and reminders for ICU patient care. (continued)

CHAPTER 1

6

Table 1–3. Things to think about and reminders for ICU patient care. (continued)

(

continued

)

Things To Think About Reminders

Hyponatremia

1. Consider volume depletion (nonosmolar stimulus for ADH secretion).

2. Consider edematous state with hyponatremia (cirrhosis, nephrotic

syndrome, congestive heart failure).

3. SIADH with nonsuppressed ADH.

4. Drugs (thiazide diuretics).

5. Adrenal insuffieiency, hypothyroidism.

1. Measure urine Na

+

, Cl

–

, creatinine, and osmolality.

2. Calculate or measure serum osmolality.

3. Volume depletion? Give volume challenge?

4. Ask if patient is thirsty (may be volume-depleted).

5. Review medication list.

6. Primary treatment may be water restriction.

7. Consider need for hypertonic saline (carefully calculate amount)

and furosemide.

8. Other treatment (demeclocycline).

Hypernatremia

1. Diabetes insipidus (CNS or renal disease, lithium?)

2. Diabetes mellitus.

3. Has patient been water-depleted for a long-time?

4. Concomitant volume depletion?

5. Is the urine continuing to be poorly concentrated?

1. Calculate water deficit and ongoing water loss.

2. Replace with hypotonic fluids (0.45% NaCl, D

5

W) at calculated rate.

3. Replace volume deficit, if any, with normal saline.

4. Measure urine osmolality, Na

+

, Cl

–

, creatinine.

5. Does patient need desmopressin acetate (central diabetes insipidus)?

Hypotension

1. Volume depletion.

2. Sepsis. (Consider potential sources; may need to treat empirically.)

3. Cardiogenic. (Any reason to suspect?)

4. Drugs or medications (prescribed or not).

5. Adrenal insufficiency.

6. Pneumothorax, pericardial effusion or tamponade, fungal sepsis,

tricyclic overdose, amyloidosis.

1. Volume challenge; decide how and what to give and how to monitor.

2. If volume-depleted, correct cause.

3. Gram-positive or gram-negative sepsis (or candidemia) may also cause

hypotension and shock.

4. Give naloxone if clinically indicated.

5. Echocardiogram (left ventricular and right ventricular function, pericardial

disease, acute valvular disease) may be helpful.

6. Does the patient need a Swan-Ganz catheter?

7. Cosyntropin stimulation test or empiric corticosteroids.

Swan-Ganz Catheters

1. Site of placement (safety, risk, experience of operator).

2. Coagulation times, platelet count, bleeding time, other

bleeding risks.

3. Document in medical record.

4. Estimate need for monitoring therapy.

5. Predict whether interpretation of data may be difficult (mechanical

ventilation, valvular insufficiency, pulmonary hypertension).

1. Check for contraindications.

2. Write a procedure note.

3. Make measurements and document immediately after placement.

4. Obtain chest x-ray afterward.

5. Level transducer with patient before making measurement; eliminate

bubbles in lines or transducer.

6. Discontinue as soon as possible.

7. Use Fick calculated cardiac output to confirm thermodilution

measurements.

8. Send mixed venous blood for O

2

saturation.

Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding

1. Rapid stabilization of patient (hemoglobin and hemodynamics).

2. Identification of bleeding site.

3. Does patient have a nonupper GI bleeding site?

4. Consider need for early operation.

5. Review for bleeding, coagulation problems.

6. Determine when “excessive” amounts of blood products given.

7. Do antacids, H

2

blockers, PPIs play a role?

8. Reversible causes or contributing causes.

1. Monitor vital signs at frequent intervals.

2. Monitor hematocrit at frequent intervals.

3. Choose hematocrit to maintain.

4. Consider need and timing of endoscopy.

5. Consult surgery.

6. Patients with abnormally long coagulation time may benefit from fresh-

frozen plasma (calculate volume of replacement needed).

7. Platelet transfusions needed?

8. Desmopressin acetate (renal failure).