Bongard Frederic , Darryl Sue. Diagnosis and Treatment Critical Care

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

CRITICAL CARE OF VASCULAR DISEASE & EMERGENCIES

657

Poldermans D et al: The effect of bisoprolol on perioperative mor-

tality and myocardial infarction in high-risk patients undergo-

ing vascular surgery. N Engl J Med 1999;341:1789–94. [PMID:

10588963]

Powell RJ et al: Effect of renal insufficiency on outcome following

infrarenal aortic surgery. Am J Surg 1997;174:126–30. [PMID:

9293827]

Raby KE et al: Correlation between preoperative ischemia and

major cardiac events after peripheral vascular surgery. N Engl J

Med 1989;321:1296–300. [PMID: 2797102]

Tepel M et al: Prevention of radiographic-contrast-agent-induced

reductions in renal function by acetylcysteine. N Engl J Med

2000;343:180–184. [PMID: 10900277]

Samson RH et al: A modified classification and approach to the

management of infections involving peripheral arterial pros-

thetic grafts. J Vasc Surg 1988;8:147–53. [PMID: 3398172]

Yusuf S et al: Effects of an angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor,

ramipril, on cardiovascular events in high-risk patients. The

Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation Study Investigators.

N Engl J Med 2000;342:145–53. [PMID: 10639539]

658

00

Alterations of consciousness including coma, seizures, and

neuromuscular disorders account for many of the neurologic

problems in patients admitted to ICUs. Therefore, this chap-

ter emphasizes encephalopathy and coma, seizures and status

epilepticus, and problems associated with neuromuscular

disorders. A comprehensive review of cerebrovascular disease

and stroke syndromes is beyond the scope of this book, but

since the critical care physician undoubtedly will have to deal

with cerebrovascular diseases, some fundamental aspects of

these disorders are described. In addition, certain aspects and

complications of CNS infectious diseases are included.

ENCEPHALOPATHY & COMA

Coma

The brain controls the individual’s ability to breathe, obtain

food and water, and avoid noxious stimuli in the environment.

When the individual slips into coma, the ability to perform

these functions is lost, and the patient will not survive unless

coma is reversed. In this sense, coma represents a global failure

of brain function. There are many causes of coma, some of

them reversible. The first responsibility of the physician caring

for a patient in coma is to ensure that breathing, circulation,

and nutrition are maintained. The cause of coma then must be

determined and reversible causes treated appropriately.

Normal consciousness has two main components: con-

tent and arousal. They have different anatomic substrates,

with the former localized largely in the cerebral cortex and

the latter depending on the brain stem reticular activating

system. Injury to the dominant cortical hemisphere leads to

impairment or loss of language function, but bilateral corti-

cal injury is required for complete loss of consciousness.

Furthermore, the cortex is responsible for interpreting

incoming signals. This includes encoding and assigning

“meaning” to emotional and sensory inputs. When the cor-

tex is diffusely injured, the ability to reflect on and interpret

experience is lost, and for this reason, the content of con-

sciousness is lost as well.

The major role of the brain stem reticular activating sys-

tem is to arouse and alert the cortex so that the organism can

reflect on and react to stimuli from the environment. A

patient can lose consciousness by two different mechanisms:

diffuse dysfunction of the cerebral cortex or injury to the

reticular activating system. Coma often develops as a result of

injury to both areas. However, cortical neurons are extremely

sensitive to a variety of metabolic and toxic injuries, includ-

ing hypoxia, hypercapnia, hyponatremia, hypernatremia,

hypoglycemia, hyperglycemia, and many drugs, whereas the

brain stem is more resistant to these injuries. Thus toxic and

metabolic injuries first cause dysfunction in cortical neu-

rons, and only with increasing severity influence the brain

stem. In contrast, coma owing to primary brain injury affects

the reticular activating system. These major anatomic differ-

ences allow the clinician to distinguish metabolic from struc-

tural causes of coma.

Neuroimaging techniques suggest that there may be a

fundamental pathophysiologic basis for many of the meta-

bolic causes of coma, perhaps explaining why so many

patients with different causes present with such similar clin-

ical profiles. In comas owing to metabolic encephalopathy, a

profound and diffuse decrease in cerebral glucose metabo-

lism has been shown using positron-emission tomography.

Similarly, severe and diffuse cerebral hypoperfusion as meas-

ured with

133

Xe appears in patients in coma owing to sepsis,

hepatic encephalopathy, hypoxia, head trauma, and cocaine

intoxication. Studies in comatose patients using

31

P magnetic

resonance spectroscopy have shown dramatic decreases in

the brain’s energy-containing phosphorus compounds,

including ATP and phosphocreatine. This work suggests that

any process that compromises cortical neuronal energy pro-

duction may lead to a comatose state.

Clinical Features

One key issue in the evaluation of any unconscious patient

is whether the unconscious state is due to metabolic,

toxic, or structural brain injury. Because there are only

30

Critical Care of Neurologic

Disease

Hugh B. McIntyre, MD, PhD

Linda Chang, MD

Bruce L. Miller, MD

Copyright © 2008 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. Click here for terms of use.

CRITICAL CARE OF NEUROLOGIC DISEASE

659

minor differences in the clinical characteristics of comatose

states owing to varying types of metabolic and toxic insults,

the clinical examination cannot definitively distinguish one

metabolic cause from another; thus the cause must be sought

or confirmed with laboratory investigations. In contrast, if

the clinical examination suggests structural brain injury,

emergency imaging tests must be performed to determine

the cause so that appropriate treatment can be initiated.

Simultaneously with the assessment of the neurologic

examination, it is critical that the physician obtain an accu-

rate history. Although a comatose patient cannot give a his-

tory, relatives, housemates, and others often describe the

onset of coma and provide information regarding medica-

tions and preexisting illnesses. Even when information from

these sources is not available, paramedics usually can provide

details about the circumstances in which the patient was

found. In all cases, a check of the patient’s pockets and purse

or wallet may help to elicit important medical data, and some

patients wear medical bracelets or necklaces, which will alert

the examiner to potential causes of coma.

Rapidity of onset is an important clue to the cause of

coma. Certain metabolic insults such as hypoxia, ischemia, or

hypoglycemia may come on suddenly, whereas others such as

hyponatremia, hypernatremia, and hyperglycemia develop

subacutely. Similarly, subarachnoid hemorrhage or brain

stem ischemic stroke can lead to sudden coma, whereas coma

related to chronic subdural hematoma, cortical ischemic

stroke, or brain tumor usually develops slowly.

The five main areas that need to be assessed in the evalu-

ation of a patient in coma are (1) level of consciousness,

(2) pupillary responses and ophthalmoscopic examination,

(3) oculomotor system, (4) motor system, and (5) respira-

tory and circulatory systems.

Based on the findings in these domains, usually it is pos-

sible to localize accurately the specific regions in the brain

that are impaired. Table 30–1 lists changes that occur with

injury in different anatomic areas of the brain. A precise

anatomic localization of the area of dysfunction in the brain

often helps to elucidate the cause of coma. Although coma

scales are helpful in assessing prognosis, they are not a sub-

stitute for neurologic examination because they neither

localize the area of dysfunction nor help in determination of

the cause.

A. Level of Consciousness—Many terms such as stuporous,

lethargic, drowsy, and semicomatose have been used to char-

acterize degrees of altered consciousness. However, it is bet-

ter to describe the patient’s spontaneous activity, response to

verbal stimuli, and reaction to painful stimuli in precise

terms that do not have different meanings to different

observers. A carefully recorded description of the patient’s

level of consciousness on entry into the hospital will be

invaluable in following the progression of the comatose state.

With herniation from a large unilateral cerebral hemisphere

mass, drowsiness occurs when the reticular activating system

in the thalamus is compressed; coma ensues when injury to

the reticular activating system reaches the midbrain.

The best places to apply painful stimuli to determine

arousability are over the sternum or the nail beds; these

maneuvers also help to determine whether the patient

responds with evidence of focality, for example, if there is no

movement of one side while the other hand attempts to

remove the painful stimulus.

B. Pupillary and Ophthalmoscopic Evaluation—Perhaps

no component of the neurologic examination is as valuable

for differentiating metabolic or toxic coma from coma owing

to structural brain disease as inspection of the pupils.

Pupillary size is determined by the relative contributions of

the parasympathetic and sympathetic autonomic fibers.

Coma associated with brain injury usually exhibits changes

in the pupillary response. These changes occur because most

structural comas are associated with injury to the reticular

activating system in the brain stem where the Edinger-

Westphal and sympathetic autonomic fibers are located.

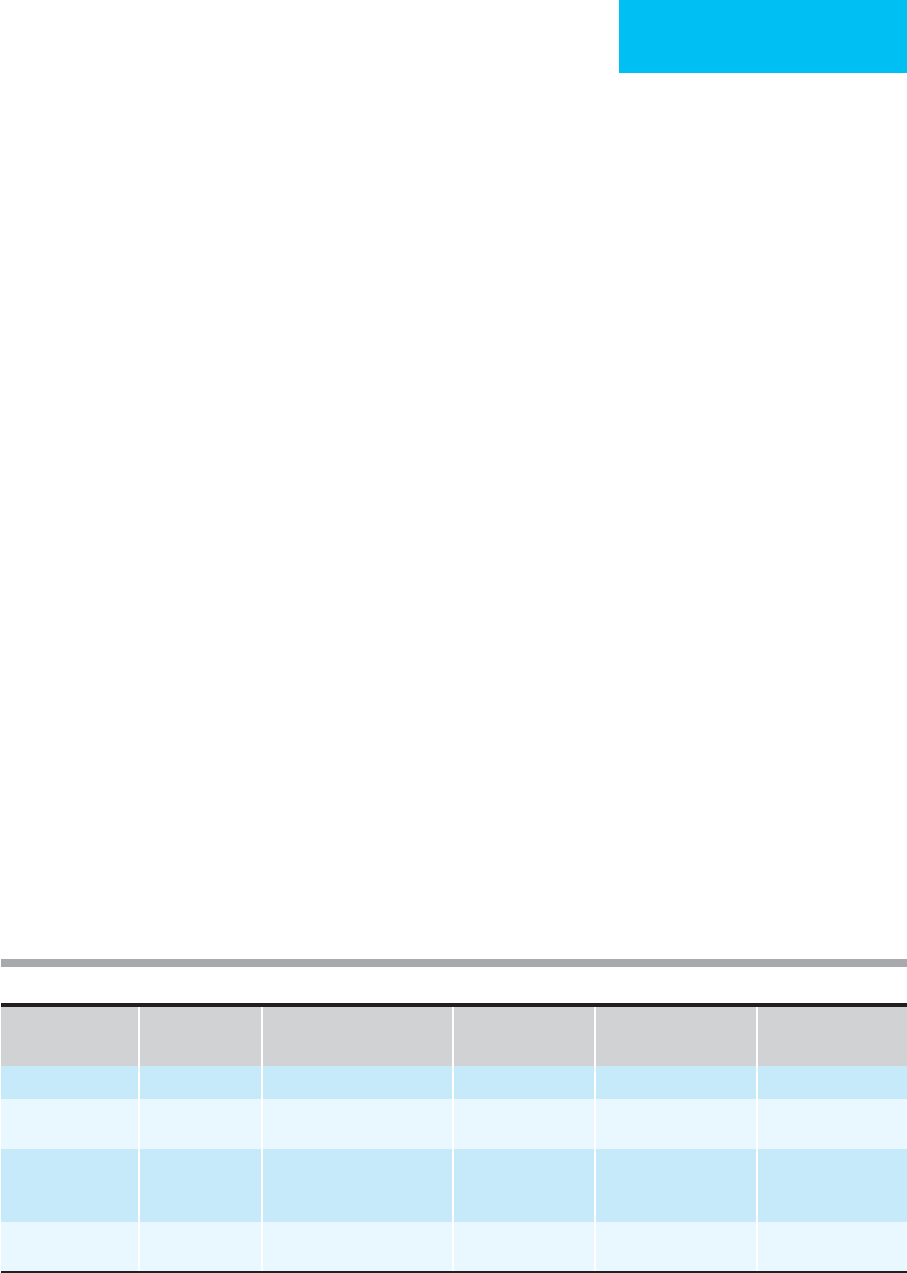

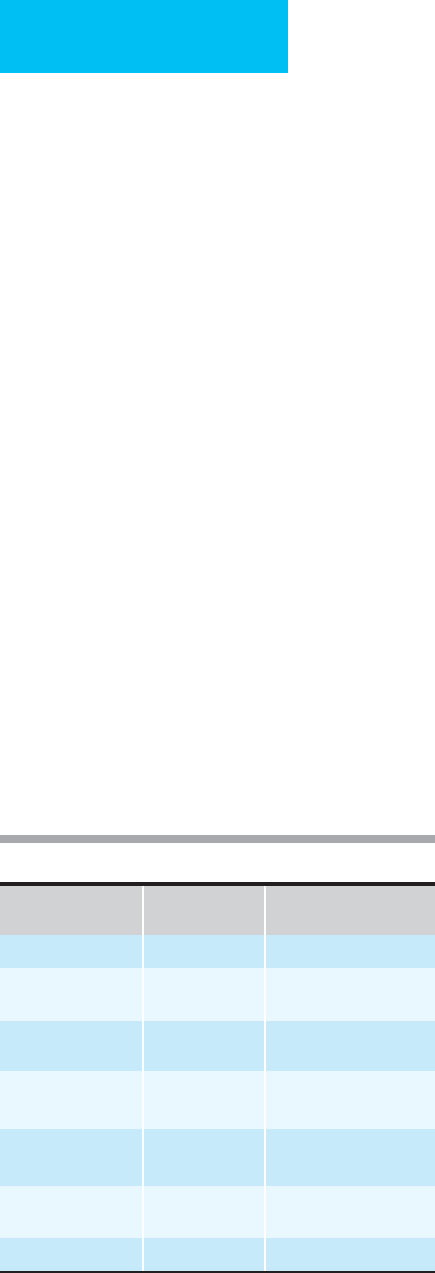

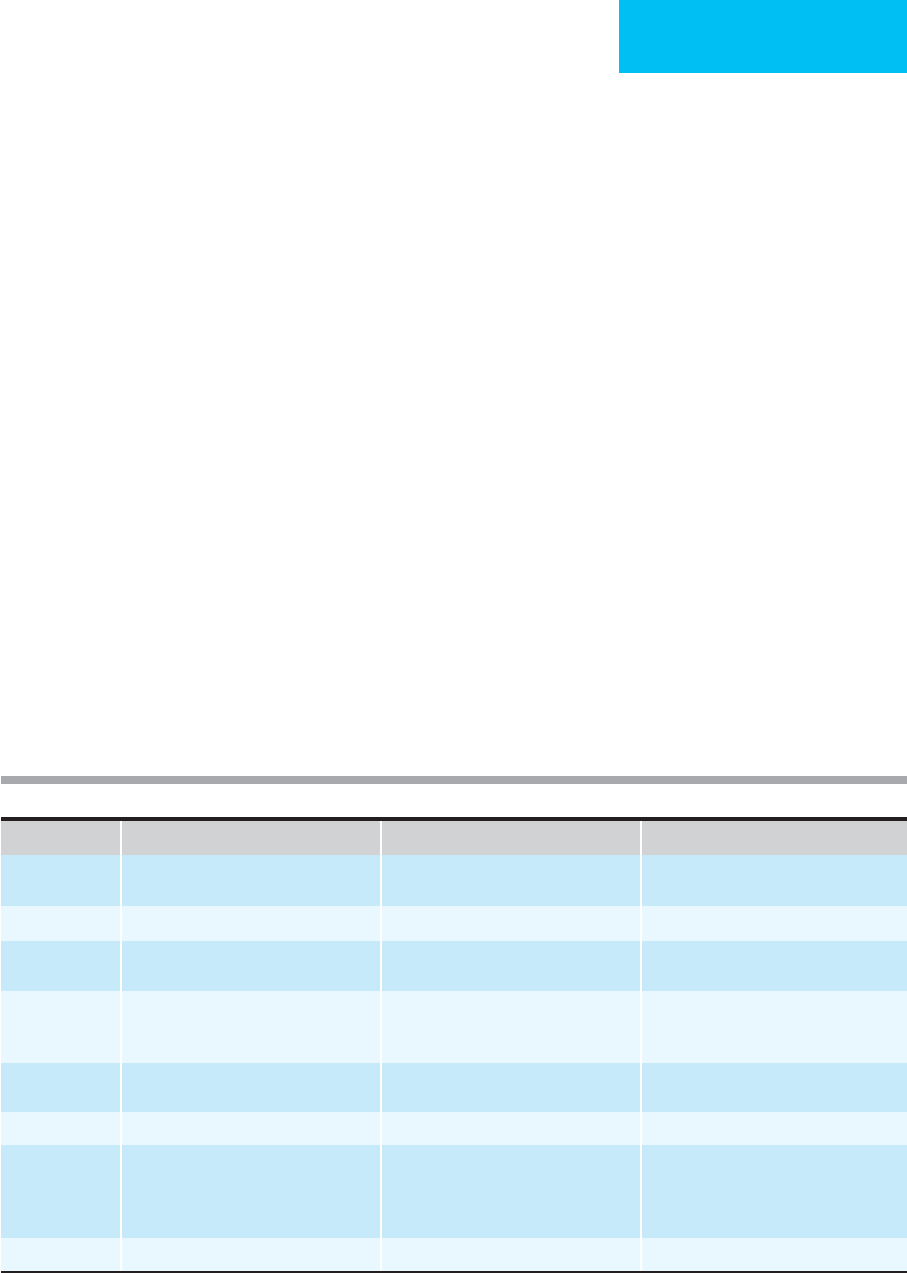

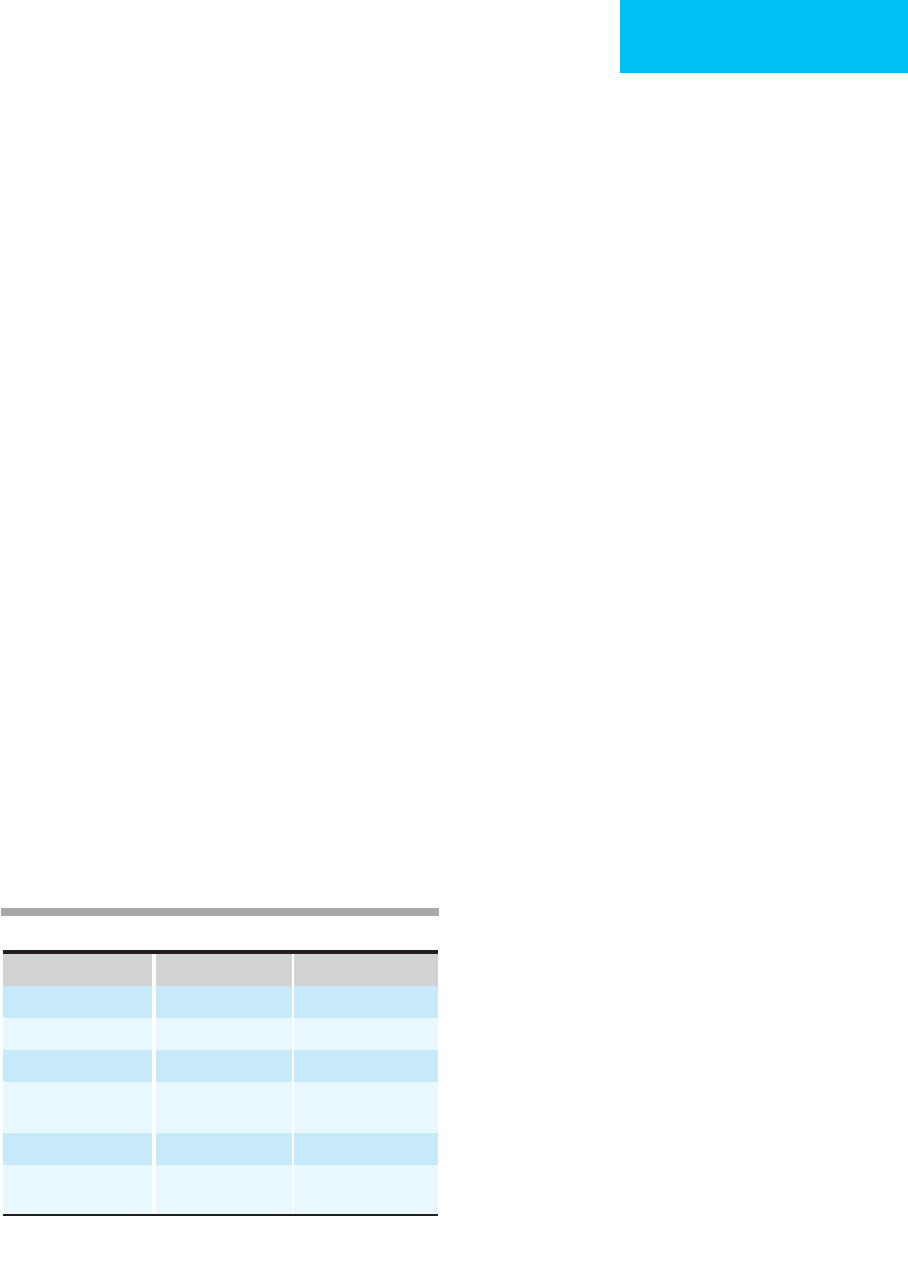

Anatomic Level Mental Status Pupillary Size and Position Eye Movement Motor Responses

Respiration and

Circulation

Diencephalon Drowsy Small (1–2 mm) Normal Abnormalities of flexion Cheyne-Stokes

Midbrain Coma Fixed in mid position Dysconjugate Abnormalities of

extension

Hyperventilation

Pons Coma 1 mm in primary pontine

injury; fixed and 4–5 mm

with prior midbrain injury

Complete paralysis Abnormalities of

extension

Hyperventilation

Medulla Variable Variable Variable Flaccid Apnea, circulatory

collapse

Table 30–1. Localization of brain lesions in a comatose patient.

CHAPTER 30

660

With acute injury to the midbrain, the pupils become fixed

in midposition as a result of simultaneous injury of sympa-

thetic and parasympathetic fibers. In contrast, injury to the

pons often is associated with pinpoint, minimally reactive

pupils. Lateral tentorial herniation of the temporal lobe may

result in compression of the third cranial nerve and the

parasympathetic fibers traveling with it, causing dilation of

the pupil on the side of the herniation. In some lateral herni-

ations there will be compression of the contralateral third

nerve against the edge of the tentorium.

A major characteristic of coma owing to metabolic dis-

eases is sparing of the pupillary response. This occurs

because metabolic coma causes selective dysfunction of the

cortex, whereas the centers in the brain stem that control the

pupils are spared. Many comas owing to drugs spare the

pupils, although some commonly used drugs do influence

the pupillary response (Table 30–2).

The ophthalmoscopic examination can provide valuable

information. Papilledema usually implies increased intracra-

nial pressure, whereas subhyaloid hemorrhage, which

appears as a fresh, red flame-shaped hemorrhage between

the retina and vitreous, is virtually pathognomonic of sub-

arachnoid hemorrhage.

Despite the importance of the ophthalmoscopic evalua-

tion, under no circumstances should the pupil be dilated in a

comatose patient because changes in the pupils are often the

most reliable clinical indication of deterioration following

brain injury.

C. Oculomotor System—As with pupillary responses,

changes in the oculomotor system often occur with primary

neurologic injury. The system responsible for moving the

eyes is located between the sixth nerve in the pons and the

third nerve in the midbrain. Closely adjacent to the sixth

nerve is a gaze center known as the pontine paramedian retic-

ular formation (PPRF). Just prior to moving one of the eyes

laterally, which is accomplished with the sixth nerve, there is

rapid firing in the PPRF. The contralateral eye will deviate

medially via fibers that travel from the PPRF, cross in the

pons, and travel medially to the contralateral third nerve

nucleus in the medial longitudinal fasciculus.

The simplest way to test the viability of this system is the

oculocephalic (“doll’s eye”) reflex. For this test, the patient is

positioned with 30-degree neck extension, and the head is

moved from side to side. If the brain stem PPRF and the

vestibular system are intact, the eyes should move smoothly

in the direction opposite to that in which the head is moved.

A more precise test is the caloric oculovestibular response.

For this test, the comatose patient is elevated to a 30-degree

angle, and one tympanic membrane is irrigated with ice-cold

water. Ten milliliters usually is sufficient to produce a

response. Within 1–2 minutes, both eyes should deviate lat-

erally toward the side where the cold water was instilled. In

metabolic or toxic coma this system is spared, whereas in

many structural comas the oculovestibular system is

impaired; in brain death, it is absent. In the normal, awake

patient, slow deviation toward the side of the stimulus is lost,

and nystagmus in the contralateral direction is observed.

D. Motor Systems—Primary brain lesions often are associ-

ated with focal motor deficits, but in metabolic or toxic

states, focal motor findings are normally absent. With lateral

cortical or internal capsular injury, the examination shows

contralateral motor deficit. Posturing in flexion (decorticate

posturing) supervenes when diffuse dysfunction of the dien-

cephalon occurs. Injury of the brain stem motor systems

between the red nucleus in the midbrain and the vestibu-

lospinal nuclei in the medulla leads to an abnormal extensor

response in the arms with flaccid or extensor response in the

legs (decerebrate posturing). Injury to motor systems at or

below the level of the vestibulospinal nuclei results in flaccid-

ity. With progressive neurologic injury, moving from higher

to lower centers, one sees a progression from paralysis to

flexor posturing to extensor posturing to flaccidity.

E. Respiratory and Circulatory Changes—With injury at

the level of the pons, abnormal respirations may occur. Once

the medulla is injured, there is loss of respiratory function,

and apnea ensues. Similarly, in the beginning stages of

medullary compression, abnormalities in blood pressure—

usually hypertension—can present. As the medullary injury

progresses, hypotension intervenes.

The first manifestation of a compressive lesion of the

medulla often is respiratory or circulatory collapse. Severe

hypertension is sometimes the first or main manifestation

of posterior fossa lesions. For these reasons, posterior fossa

lesions are difficult to diagnose and can be catastrophic

when missed.

Drug Type

Pupillary

Response

Other Changes

Opioids Pinpoint None

Barbiturates and

benzodiazepines

Reactive None

Anticholinergics

(scopolamine, etc.)

Pupils dilated Tachycardia, seizures

Anticholinesterases

(organophosphates)

Pupils constricted Bradycardia, sweating,

salivation

Cocaine and

amphetamine

Pupils dilated Tachycardia, hypertension,

hypotension, arrhythmia

Neuroleptics Pupils variable Motor rigidity,

hypotension, hyperthermia

Antidepressants Pupils dilated Rarely seizure

Table 30–2. Physical findings in drug-induced comas.

CRITICAL CARE OF NEUROLOGIC DISEASE

661

Differential Diagnosis

The major group of diseases that cause coma include meta-

bolic, toxic, and primary neurologic injury. The cause usually

can be determined by neurologic examination.

A. Metabolic Coma—In any patient with unexplained coma

suggesting metabolic dysfunction, it is important to measure

serum sodium, glucose, urea nitrogen, and creatinine; to

determine Pa

O

2

and Pa

CO

2

; and to perform liver and thyroid

function tests. A toxicology screen also is mandatory. Sepsis

can lead to coma, and evidence for infection should be sought

in any delirious or comatose patient. The physician should

have a low threshold for obtaining lumbar puncture for cere-

brospinal fluid (CSF) analysis in a patient with unexplained

coma. Comas owing to various metabolic factors have more

similarities than differences. Table 30–3 lists the major meta-

bolic causes of coma and comments on subtle differences in

coma owing to these various metabolic abnormalities.

Elderly people are particularly vulnerable to the effects of

metabolic insults and poorly tolerant of mild fluctuations in

metabolic status. Therefore, it is common to observe an eld-

erly patient in coma owing to relatively mild metabolic

abnormalities, whereas this same combination of metabolic

changes might not lead to coma in a young, otherwise

healthy individual. One typical example is the elderly patient

who develops delirium or even coma associated with a

pulmonary or urinary tract infection. In fact, elderly

patients’ changes in mental status sometimes are the first

manifestation of sepsis. Many patients with primary brain

injury, however, demonstrate mild metabolic abnormalities,

and one should not automatically assume that subtle meta-

bolic changes explain why a patient is in coma.

B. Toxic Coma—Coma secondary to drugs often resembles

coma from other metabolic processes. However, respiratory

suppression may be more common in patients with drug-

induced coma. Similarly, some groups of drugs have specific

effects on the pupils. The drugs that can cause coma are too

numerous to list in this chapter. Table 30–2 lists some com-

monly abused drugs and emphasizes the characteristics of

coma associated with drug overdose.

C. Primary Brain Injury—CNS infection, trauma, and

stroke can lead to coma. Massive rises in intracranial pressure

such as those seen with severe head injury, subarachnoid

hemorrhage, or blockage of CSF flow by a ventricular mass

cause sudden coma. Coma also occurs with acute injury to

the reticular activating system in the brain stem owing to

basilar artery thrombosis or pontine hemorrhage. In any

patient with altered consciousness and focal motor findings,

it should be assumed that a focal brain lesion is present.

Once it has been determined that a primary neurologic

event is a possible cause of the coma, emergency scan of the

brain is required. CT generally can be done quickly, is very

sensitive for acute hemorrhage, and demonstrates most focal

injuries. However, many patients with coma secondary to

ischemic brain injury, isodense subdural hematomas,

encephalitis, and meningitis will not show changes on CT

unless contrast material is used. If readily available, MRI is a

Disease Coma Mechanisms and Features Treatment

Hyponatremia Acutely: <120 meq/L

Chronically: <110 meq/L

Leads to true cytotoxic edema.

Skin can be doughy.

Hypertonic saline. Overly rapid correction

may lead to central pontine myelinolysis.

Hypernatremia >155 meq/L Loss in brain water. Seizures common. Slow rehydration.

Hypoglycemia <30 meq/dL Deprivation of brain glucose for energy

metabolism. Seizures are common.

Needs urgent glucose replacement.

Hyperglycemia Ketotic or nonketotic Changes in brain water and pH contribute

to both. Nonketotic coma often has

focal findings.

Slow correction.

Hypoxia Pa

O

2

usually <40 mm Hg Loss of brain O

2

for aerobic

metabolism.

Needs urgent correction.

Renal failure Variable Brain acidosis is a factor. Renal dialysis.

Hepatic failure Variable. Often precipitated by medications

or gastrointestinal bleeding

Brain ammonia and changes in glutamine

or dopamine hypothesized as causes.

Hyperventilation and decerebrate

posturing.

Treat precipitating factor.

Lactulose administration.

Hypothyroidism Chronic low levels Clinical findings of myxedema. Slow thyroid hormone replacement.

Table 30–3. Metabolic comas: mechanisms and treatment.

CHAPTER 30

662

good choice, although the imaging process takes longer than

CT scanning and is more expensive. Cerebral blood flow

imaging, single-photon-emission computed tomography

(SPECT), and diffusion MRI also may be helpful in the eval-

uation and management of patients with acute brain injury.

D. Brain Death—The diagnosis of brain death is an

unavoidable issue in the practice of critical care medicine

and must be approached with sensitivity to the patients’ close

associates and an awareness of the possibility of organ dona-

tion. When brain death appears likely, a frank discussion

with family members usually is indicated. It should be recog-

nized that spinal reflexes and even myoclonus may persist in

the brain-dead patient and can be misunderstood both by

medical personnel and by family members. Declaration of

brain death requires the demonstration of irreversible loss of

both brain stem and cerebral function and should be done in

consultation with a neurologist. Permanent loss of cerebral

function with preservation of brain stem function is termed

the chronic vegetative state, and current practice requires that

such patients be given appropriate supportive care.

Treatment

The first step in the management of a patient in coma is to

secure the airway and ensure adequate oxygenation. This

may require intubation. Furthermore, intubation should be

considered when control of Pa

CO

2

is necessary. Hypercapnia

causes cerebral vasodilation, and hypocapnia causes vaso-

constriction; the former can increase intracranial pressure,

and the latter can reduce it. In addition, aspiration is a com-

mon problem in the patient with altered consciousness and

another reason to consider intubation.

Just as important in the management of coma is the quick

assessment and control of the circulatory system. Even in

patients with initially normal blood pressures, sudden loss of

systemic perfusion can occur and can lead to irreversible brain

injury. Therefore, a large-bore intravenous catheter should be

placed in all comatose patients so that circulatory access is

assured. Following this and when dealing with an unknown

cause, 100 mg thiamine and then a bolus of dextrose should be

administered as treatment for potential cases of Wernicke’s

encephalopathy or hypoglycemia. In many patients with brain

lesions and increased intracranial pressure, reflex systemic

hypertension occurs. In the case of cerebellar or ventricular

mass lesions, focal findings may be subtle or even absent and

can lead to the incorrect assumption that the coma is due to

hypertension and the primary problem ignored. Unexpected

herniation can occur in such patients. Irrespective of the cause

of increased intracranial pressure, lowering of systemic blood

pressure could result in loss of cerebral perfusion.

Once respiration and circulation are maintained, the

focus is on treatment appropriate to the diagnosis. The next

chapter outlines the management of coma owing to

increased intracranial pressure. Many metabolic causes of

coma such as hypernatremia, hyponatremia, hyperglycemia,

and hepatic encephalopathy have protocols that demand

meticulously organized treatments that often require days.

Similarly, drug-induced comas may require specific treat-

ment. In coma owing to barbiturate or benzodiazepine tox-

icity, simply maintaining respiratory and circulatory

support until the drug is cleared will be sufficient, whereas

other poisons may require administration of specific anti-

dotes (see Chapter 37).

SEIZURES

All physicians in critical care medicine on occasion will have

to manage seizures, which may be seen as the patient’s pri-

mary problem or as a problem complicating other illnesses.

Prompt recognition and treatment of seizures are important

because prolonged or frequently repeated generalized

seizures may lead to permanent brain injury.

The basic functional property of neurons is electrochem-

ical, and the basic disturbance of this property that underlies

all seizures is termed the paroxysmal depolarization shift. The

various lesions that produce seizures result in a paroxysmal

production of synaptic potentials, which brings neurons

above their threshold and causes repetitive action potentials.

Thus the electrochemical disturbance is propagated, and

clinical seizures result.

Seizures may occur as a result of substrate deprivation,

synaptic dysfunction, or brain injury or as a manifestation of

primary generalized epilepsy. The brain depends on two

major substrates—oxygen and glucose—and deprivation of

either may result in seizures. Similarly, sodium is required to

maintain the electrochemical property of neurons, and

extreme changes in sodium concentration also can lead to

seizures. In general, the magnitude of hypoglycemia,

hypoxia, and hyponatremia must be great enough to result in

alteration of consciousness, following which seizures occur.

Similarly, various toxic insults can result in seizures by alter-

ing synaptic function.

Direct brain injury may cause seizures, both acutely and in

delayed fashion. In acute head injury, mechanical factors

probably disturb membrane function, and the resulting

seizures are seen within minutes to hours following the

trauma. These seizures may be limited and do not typically

recur. Brain injury from laceration in open head wounds or

direct tissue damage in closed head injury may result in post-

traumatic seizures. Pathologically, this occurs after healing

and gliosis have taken place at the injured site. Typically, these

seizures begin a few months to a year following trauma. The

precise nature of this “ripening” process is unclear, but den-

dritic abnormalities have been observed on surviving neurons

in the areas of gliosis. Direct electric shock also can cause

seizures and is a classic method for testing the effectiveness of

proposed anticonvulsant medications in animal models.

Finally, a common cause of seizures is primary generalized

epilepsy. The precise pathophysiologic mechanisms are

unknown, but most investigators believe the disturbance

probably is related to ion channel, neurotransmitter, and

CRITICAL CARE OF NEUROLOGIC DISEASE

663

synaptic dysfunction. Potential insights into the pathophysiol-

ogy of primary generalized epilepsy are provided by the pro-

posed mechanism of action of anticonvulsant medications.

For example, phenytoin and carbamazepine are thought to act

at sodium channels, whereas valproic acid is thought to act at

sodium and calcium channels. In addition, a great deal of

investigation with valproic acid concerns its action on γ-

aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptors. Phenobarbital has been

found to block posttetanic potentiation produced by elec-

troshock and also may act at calcium and chloride channels.

Classification of Seizures

Recognition and understanding of the seizure type is the first

step in the evaluation process and serves as a guide for

workup and management. The types of seizures are summa-

rized in Table 30–4.

A. Partial Seizures—Partial seizures are those that arise

from a focal area of the cortex. The clinical nature of the

seizure is dictated by the functional specialization of the cor-

tical area from which it arises. Focal motor seizures are a

good example. Note that a seizure is an activation of function

and not a loss of function, as occurs in a transient ischemic

attack. Partial seizures that are limited and not associated

with alteration of consciousness are termed simple partial

seizures. Impairment of consciousness coupled with a partial

seizure is called a complex partial seizure.

Complex partial seizures generally arise from the tempo-

ral lobe or other limbic structures. At the onset of this type

of seizure, the patient commonly experiences some auto-

nomic or emotional symptoms, such as a feeling of fear, asso-

ciated with a rising or breathless sensation within the chest

or a sense of being startled. Abdominal sensations are

reported commonly. The patient may experience other phe-

nomena such as déjà vu or may experience visual or olfactory

hallucinations. These altered perceptions tend to be stereo-

typed from seizure to seizure in any given patient and are

usually brief in duration. Following this type of onset, the

patient has an alteration of consciousness and usually has lit-

tle memory of what occurs until the seizure is completed.

To an observer, the onset of a complex partial seizure may

appear only as a motionless stare. After the onset, the patient

may develop some type of automatic and repetitive move-

ments. Examples are lip smacking or movements of one or

both extremities or repetitive picking at some part of the

body or a piece of clothing. During this time, the patient is

poorly responsive to the environment but still may have

some limited interaction. The patient then seems to recover

but remains confused for variable periods, usually only a few

minutes. Most seizures last from a few minutes to about

15 minutes. In repetitive, frequent complex partial seizures,

the patient seems to be in a twilight state, awake yet poorly

responsive to the examiner and the environment.

B. Generalized Tonic-Clonic Seizures—These were at one

time called grand mal seizures. Such seizures are sometimes

preceded by a cry. They are always accompanied by loss of

consciousness, but the tonic and clonic phases are variable.

The tonic phase usually precedes the clonic phase, and all the

extremities are involved in both phases. During the tonic

phase, there is expression of extensor motor dysfunction,

whereas throughout the rhythmic clonic phase, there is flexor

motor predominance. The duration of a single generalized

seizure is measured in minutes, and there always will be a

period of postictal confusion that is likewise usually brief.

Generalized tonic-clonic seizures may develop as a conse-

quence of spread from a partial seizure; in this instance, it

would be designated as secondarily generalized. Tonic-clonic

seizures, generalized at onset, may be caused by metabolic

abnormalities, drug withdrawals, poisons, or other patho-

logic states that affect overall brain function. Primary gener-

alized epilepsy is a major cause of generalized tonic-clonic

seizures. However, the essential pathogenesis of primary gen-

eralized epilepsy is poorly understood. In general, the pri-

mary generalized epilepsies (both generalized and absence)

have their onset in childhood.

C. Absence Seizures—Typical absence seizures were for-

merly called petit mal seizures. They are due to another type

of primary generalized epilepsy and always begin abruptly

with the patient losing cognitive contact. There may be some

fluttering of the eyelids, but body tone is maintained, and the

patient does not fall. Typically, after a few moments (occa-

sionally up to 1 minute or longer), the patient abruptly

regains awareness and will continue the interrupted activity.

Some patients recognize that the period of absence has

occurred, but others do not. This type of seizure is not asso-

ciated with a postictal state. The EEG shows generalized three

per second spike-and-wave discharges during the seizure.

Characteristically, the discharges are provoked by hyperven-

tilation. Absence seizures can be very frequent and pro-

longed—a condition referred to as absence status.

D. Status Epilepticus—Status epilepticus exists whenever

seizures are persistent or there is incomplete recovery

between seizures. Generalized tonic-clonic status epilepticus

is a medical emergency. The consequences of status can

Simple partial (focal seizure with preservation of consciousness)

Complex partial (focal seizure with alteration of consciousness)

Secondarily generalized tonic-clonic

Primarily generalized tonic-clonic (grand mal)

Absence (petit mal)

Status epilepticus

Convulsive tonic-clonic

Nonconvulsive

Absence

Partial (epilepsia partialis continua)

Table 30–4. Classification of seizures.

CHAPTER 30

664

include aspiration pneumonia, hypoxia, hypotension, hyper-

thermia, autonomic instability with cardiac arrhythmias,

hyperkalemia, lactic acidosis, myoglobinuria, decreased

cerebral perfusion, and death. Furthermore, prolonged gen-

eralized tonic-clonic seizures can result in permanent neu-

ronal injury, particularly in the hippocampus, cerebellum,

and neocortex.

In nonconvulsive status, the patient has impairment or

loss of consciousness without generalized motor seizures.

Nonconvulsive status can be quite subtle and difficult to rec-

ognize in the critical care setting. The patient may show an

occasional twitch of an extremity or a facial twitch.

Sometimes the only evidence for seizure activity involves eye

movements, which can be observed only by lifting the eye-

lids. Nonconvulsive status of this type often is associated

with significant metabolic encephalopathy and sometimes

with underlying structural brain disease. Electroence-

phalography is required for diagnosis.

Another type of generalized nonconvulsive status is

absence status, also called spike-wave status. Absence status

most often occurs in children who have generalized epilepsy.

In adults it is rare, but it may occur suddenly in elderly

patients and present as a confusional state with minor

automatisms such as eye blinking or facial twitching.

Status epilepticus also can occur with partial seizures.

This has been called epilepsia partialis continua, and focal

motor seizures are the type most apt to be seen by the criti-

cal care physician. Complex partial status presents with a

patient in a confusional state, often with various automa-

tisms as described previously.

Clinical Features

A. History and Examination—The history is critical in the

diagnosis of seizures, and a comprehensive review of the his-

tory and the hospital course is required. Patients may

describe their symptoms, particularly in the case of complex

partial seizures; however, many patients are unaware of activ-

ity during the episode because consciousness has been

impaired. In fact, patients are sometimes even unaware that

they have had a lapse of consciousness. Thus it is important

to obtain a history from the patient and from witnesses such

as nurses, other patients in the room, family members, or

other attending physicians. Neurologic examination should

be directed toward signs of metabolic encephalopathy,

increased intracranial pressure, and lateralized findings

indicative of focal brain disease. An EEG may help to clarify

the nature of the seizure, particularly if it is obtained during

or soon after the seizure activity. Unless an obvious cause for

a seizure is known (eg, medication noncompliance in a

patient who has a known and previously evaluated seizure

disorder), brain imaging is necessary to see if structural brain

disease is present. If an infectious cause is suspected and there

is no contraindication owing to intracranial mass effect, lum-

bar puncture should be performed to obtain CSF for exami-

nation. If mass effect is present, neurosurgical consultation

should be obtained.

With new-onset seizures in the critical care setting, a use-

ful approach is to consider reversible causes first. In most

instances, these seizures will be generalized, tonic-clonic in

nature. Hypoxic-ischemic events are a common cause of

such seizures. The magnitude and duration of brain oxygen

deprivation will determine the severity of the seizure, as well

as the ultimate outcome. A brief seizure or several brief

seizures with rapid resolution may require no anticonvulsant

therapy. If the hypoxia-ischemia is severe, the seizures may be

prolonged and difficult to treat, and hypoxia-ischemia also

may be a cause of nonconvulsive status epilepticus.

The most common causes of drug-withdrawal seizures are

ethanol, barbiturates, and opioids. Ethanol-withdrawal seizures

usually occur after 24–72 hours of abstinence and rarely lead to

status epilepticus unless there are other underlying diseases.

Theophylline is probably the most common pharmacologic

cause of seizures in the ICU. Lithium toxicity may cause an

encephalopathy that may include seizures. Penicillin toxicity

causes seizures but is a rare occurrence usually associated with

kidney failure. A more common metabolic cause of seizures is

hyponatremia, which often is associated with inappropriate

antiduretic hormone secretion, and/or fluid overload.

Seizures occurring with acute neurologic disease often are

partial, or partial with secondary generalization, and the par-

tial onset may not be clinically apparent. Herpes simplex

encephalitis tends to be focal, whereas encephalitis from

other causes is more generalized. Electroencephalography

and imaging studies are helpful in the differential diagnosis.

Seizures usually do not occur with uncomplicated meningi-

tis. If they occur in bacterial meningitis, one should suspect

a complicating cortical venous thrombosis. Brain abscesses

commonly cause seizures.

The EEG is very useful in critical care neurology. To obtain

the maximum information from the EEG, the clinician

should provide the electroencephalographer with a brief his-

tory that includes the patient’s age, a description of the level

of consciousness, and a list of the medications being admin-

istered. One syndrome that can be defined with the EEG is

called periodic lateralized epileptiform discharges (PLEDs).

Affected patients are stuporous or comatose, may have occa-

sional epileptiform twitching movements of one side of the

face, and show the characteristic lateralized epileptiform dis-

charges. PLEDs usually are associated with some underlying

structural brain disease, such as an old infarct, and a superim-

posed metabolic encephalopathy. In general, the prognosis is

hopeful with correction of the metabolic disturbance and,

usually, administration of anticonvulsant medication.

In the case of seizures, the EEG can be diagnostic if

obtained during the seizure, but also it may show interictal

discharges and abnormalities supportive of the diagnosis and

indicate any focal aspect. Sometimes it is helpful to employ

closed-circuit TV, together with an electroencephalographic

monitoring system, to fully evaluate the seizure as well as the

progress of therapy. The EEG also is helpful in establishing

the diagnosis of a generalized toxic-metabolic encephalopathy

whether or not seizures are present.

CRITICAL CARE OF NEUROLOGIC DISEASE

665

Differential Diagnosis

Seizures may be associated with many different pathologic

states, including structural disease owing to neoplasms, vas-

cular anomalies, old strokes, and past trauma, or metabolic

encephalopathies. Other common problems leading to

seizures include poisoning, drug withdrawal, infections such

as viral encephalitis, and primary generalized epilepsies. Poor

compliance with the anticonvulsant regimen is a common

reason for a patient with epilepsy to develop status epilepti-

cus as well as to have poor seizure control. Drug level moni-

toring in these patients is essential.

Partial seizures of any type imply an underlying struc-

tural brain disease. Likewise, a postictal paresis (Todd’s pare-

sis) implies underlying focal disease.

Treatment

The management of seizures in critical care practice requires

first the removal or correction of precipitating causes and sec-

ond the administration of anticonvulsant medication. Often

it will seem prudent to administer anticonvulsant medication

on a temporary basis while causative conditions are resolving.

Whether anticonvulsants are administered orally or intra-

venously, it is critical to monitor serum concentrations to

ensure a therapeutic range. Phenytoin (fosphenytoin IV

preparation fully converted to phenytoin after injection),

phenobarbital, and valproate can be administered either

intravenously or orally. Lorazepam and diazepam are useful

anticonvulsants only when given intravenously.

Table 30–5 lists the doses and average half-lives of these

anticonvulsant medicines administered intravenously. Since

these half-lives are variable, the information provides an

approximation of the duration of action.

The major limiting factor for diazepam is that it peaks

into the therapeutic range for only a brief time; seizures may

recur 15–20 minutes after it is given. On the other hand, it is

rapidly effective. There may be some risk of apnea when

diazepam and phenobarbital are given together. Lorazepam

also is rapidly effective and has a longer duration of action.

The dose of lorazepam is usually 2–10 mg, or 0.1 mg/kg. It

can be administered in 2-mg increments at intervals of a few

minutes until the seizures are controlled or the maximum

dose is reached.

Both fosphenytoin or phenytoin and phenobarbital are

effective anticonvulsants, although their onset of action may

be slower than that of the benzodiazepines. Phenytoin, phe-

nobarbital, and valproate can be continued orally. Phenytoin

must be administered at a rate no faster than 50 mg/min

because of the risk of cardiac arrhythmia. Electrocardiographic

monitoring is advised while phenytoin is given. Phenytoin

should not be mixed in a dextrose solution because it will pre-

cipitate. The initial intravenous dose is 18–20 mg/kg of body

weight; the maximum dose is 30 mg/kg. Fosphenytoin is

dosed in phenytoin equivalents (PEs); it can be mixed in nor-

mal saline or a 5% dextrose solution and infused at a rate up

to 150 mg PE per minute. Extravasated phenytoin solution

often is harmful to surrounding tissues, whereas extravasated

fosphenytoin usually results in no tissue damage.

The intravenous dose of phenobarbital is 300–1000 mg

(or 15–20 mg/kg) for seizure control. Usually it is supplied

in 60-mg units, so an initial dose of 300 mg is convenient and

can be repeated every 10–20 minutes until seizure control

occurs or the maximum dose is reached.

Valproate sodium injection is a broad-spectrum anticon-

vulsant; it has complete bioequivalence with oral valproate and

may be mixed in normal saline or 5% dextrose solution. The

recommended infusion rate is up to 20 mg/min. Valproate is

the drug of choice for absence seizures. Intravenous valproate,

lorazepam, and diazepam are effective in absence status.

Levetiracetam also is available as an intravenous solution

as well as an oral preparation. It is approved as adjunctive ther-

apy in the treatment of partial-onset seizures in adults when

oral administration is not feasible. The intravenous dose is

equivalent to the oral dose (1000–3000 mg/day given twice daily)

and is supplied in 500-mg/5-mL vials. It should be diluted in

100 mL normal saline and infused over 15 minutes.

Levetiracetam is 66% excreted unchanged in the urine and has

no metabolism involving hepatic cytochrome P450 isoenzymes.

Seizures from metabolic encephalopathies, nonconvul-

sive status, and PLEDs often do not respond fully and quickly

to anticonvulsive medications. In this circumstance, it is best

to maintain therapeutic anticonvulsant blood concentrations

while pursuing therapy of underlying diseases. Partial

seizures or partial status likewise may be resistant to treat-

ment. In such cases, two anticonvulsant drugs can be tried,

but it is best to maintain them in the usual therapeutic range

and determine if with time there is greater benefit.

Generalized tonic-clonic status epilepticus does consti-

tute an emergency and must be controlled. Ventilation and

cardiac function must be supported. If hypoglycemia is a

consideration, 50 mL of a 50% dextrose solution should be

Drug Average Half-Life Dose

∗

Diazepam 1 hour 10–30 mg

Lorazepam 3 hours 2–10 mg

Phenytoin 12 hours 18–20 mg/kg

Fosphenytoin

12 hours

†

20 mg phenytoin

equivalents (PE)/kg

Phenobarbital 99 hours 15–20 mg/kg

Valproate sodium

injection

‡

10 hours 250–500 mg

∗

Status epilepticus or loading.

†

Converted to phenytoin in 10–15 minutes.

‡

T

MAX

= 1 hour.

Table 30–5. Intravenous anticonvulsants.

CHAPTER 30

666

administered promptly. If there is any possibility that the

patient is an alcoholic, dextrose should be preceded by

100 mg thiamine to prevent Wernicke’s encephalopathy.

Anticonvulsant medication for status epilepticus always

must be administered intravenously and be given in full

loading doses. A common mistake is to give inadequate

amounts of several different drugs.

If generalized tonic-clonic seizures persist despite the

patient’s being given intravenous anticonvulsants, pentobar-

bital anesthesia is recommended. This should be accomplished

with neurologic consultation and under electroencephalo-

graphic control. Pentobarbital is given in a dosage of 5 mg/kg

for induction of anesthesia and 0.5–2 mg/kg per hour for

maintenance. The drug is administered so as to titrate the EEG

to a burst-suppression pattern. When it is judged that an

appropriate interval of time has lapsed (about 24–48 hours),

the pentobarbital dose may be reduced to test for seizure

recurrence. If the seizures are controlled, the pentobarbital

may be withdrawn, but therapeutic levels of an anticonvulsant

such as phenytoin must be present and maintained.

Current Controversies and Unresolved Issues

Resistant partial or lateralized seizures and nonconvulsive

generalized status epilepticus remain problems in manage-

ment, and there is some uncertainty about how vigorous the

physician should be in the administration of medications.

No absolute indication exists for the choice of first med-

ication to treat generalized tonic-clonic status; rather, it is a

matter of common practice and personal choice.

In the past few years, the number of oral antiepileptic drugs

available has increased dramatically, and experience with them

in daily practice is accumulating but is not yet great. Use of

these drugs, as well as other treatments, including surgical and

vagus nerve stimulation, and the management of chronic

seizure disorders are mostly beyond the scope of critical care

practice. Neurology consultation is recommended when newly

prescribing or switching oral antiepileptic medicine.

NEUROMUSCULAR DISORDERS

Respiratory failure and cardiac failure are the most serious

potential complications of neuromuscular diseases and can

lead to death if not treated appropriately. Diseases directly

affecting respiration include Guillain-Barré syndrome,

myasthenia gravis, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and

Duchenne’s muscular dystrophy. Less commonly, botulism,

tetanus, porphyria, and diphtheritic polyneuropathy cause

neuromuscular failure. Similarly, a number of neuronal poi-

sons can lead to severe weakness and even respiratory fail-

ure. Chronic neuromuscular diseases can lead to secondary

pulmonary problems, including phrenic nerve injury,

kyphoscoliosis, pulmonary emboli, atelectasis, and most fre-

quently, aspiration pneumonia. Another potential problem

associated with neuromuscular diseases involves cardiac

complications such as arrhythmias, as seen in Guillain-Barré

syndrome, or conduction blocks with sudden death, as seen

in myotonic dystrophy. Advances in the ICU treatment of

these patients have decreased morbidity and mortality rates,

avoiding sudden death in some instances.

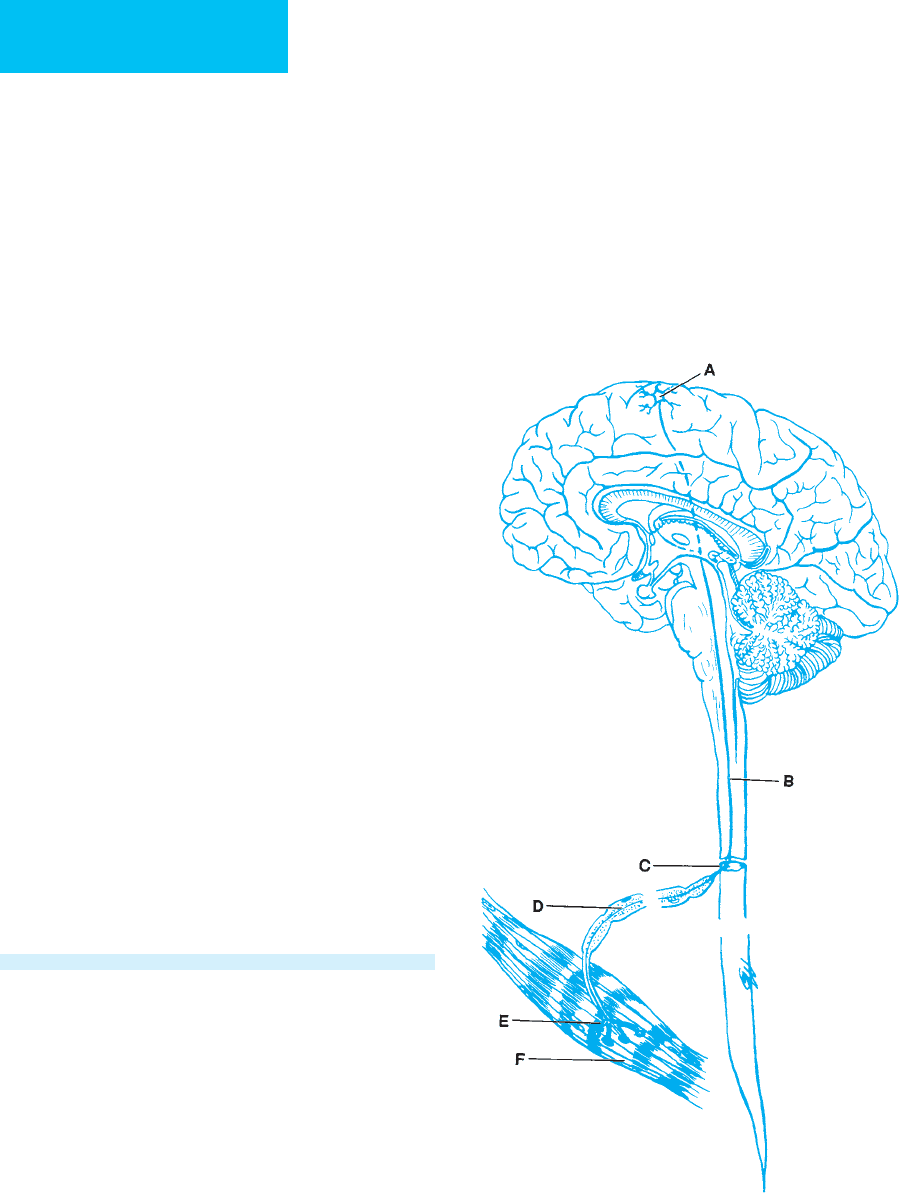

Pathophysiology

Progressive weakness may result from disorders anywhere

along the motor tract (Figure 30–1). Lesions in the brain,

particularly the upper motor neuron pathways (site A) or

Figure 30–1. Localization of lesions causing neuro-

muscular diseases. A. Cortex (upper motor neuron).

B. Spinal cord. C. Anterior horn cell. D. Peripheral nerve

(axon or myelin). E. Neuromuscular junction. F. Muscle.