Bongard Frederic , Darryl Sue. Diagnosis and Treatment Critical Care

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

DERMATOLOGIC PROBLEMS IN THE INTENSIVE CARE UNIT

627

myocarditis, encephalitis, and DIC also may occur along with

extensive hemorrhagic skin lesions.

In the normal host, herpes zoster is an acute, self-limited,

usually painful unilateral eruption in a dermatomal distribu-

tion. Characteristically, clusters of vesicles occur on a back-

ground of erythema. Occasionally—especially in persons

with compromised immune systems—herpes zoster may

become severe and necrotic. Wide dissemination of multiple,

small, varicella-like vesicles may develop. In such patients,

secondary bacterial infection is an added risk.

B. Laboratory Findings—A Tzanck smear demonstrates

diagnostic multinucleated epithelial giant cells. This test is

performed by scraping the base of a vesicular lesion with a

scalpel blade, transferring the material to a glass slide, and

staining with Giemsa’s or Wright’s stain. The Tzanck smear is

also positive in HSV infections. Culture of a lesion may con-

firm the diagnosis but requires approximately 10 days of

growth. An immunofluorescent antibody test using materials

from a lesion is also available. Acute and convalescent sera

may be helpful.

Differential Diagnosis

Varicella may be confused with widespread impetigo, dis-

seminated herpes zoster, disseminated herpes simplex,

eczema herpeticum, and smallpox. Eczema herpeticum is a

widespread cutaneous infection with HSV occurring in

patients with preexisting skin disorders such as atopic der-

matitis. The lesions in smallpox begin as red macules and

evolve in synchrony through vesicular and pustular stages,

and they predominately affect the face and extremities.

Treatment

Systemic acyclovir in the doses listed is recommended in the

following situations: (1) All VZV infections in immunocom-

promised individuals (10 mg/kg intravenously every 8 hours

for 7–10 days), (2) varicella in teenage and adult patients

(800 mg orally five times a day for 5–7 days), and (3) elderly

patients and patients with severe, painful, or destructive

zoster when seen within 48–72 hours after onset (800 mg

orally five times a day for 7 days). Alternative drugs for acute

herpes zoster are famciclovir, 500 mg three time daily for

7 days, and valacyclovir, 1 g three times daily for 7 days.

Secondary bacterial infection should be treated aggres-

sively. Cool compresses and antihistamines may help to

remove crusts and alleviate pruritus. Analgesics should be

provided as necessary.

Dworkin RH et al: Recommendations for the management of her-

pes zoster. Clin Infect Dis 2007;44:S1–26. [PMID: 17143845]

Gardella C, Brown ZA: Managing varicella zoster infection in preg-

nancy. Cleve Clin J Med 2007;74:290–6. [PMID: 17438678]

Heininger U, Seward JF: Varicella. Lancet 2006;368:1365–76.

[PMID: 17046469]

Rubeola (Measles)

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Incubation period of 7–14 days, followed by high

fever, malaise, cough, coryza, and conjunctivitis with

photophobia.

Three to 5 days later, discrete erythematous macules

and thin papules appear on the forehead and behind

the ears, spreading to the trunk and extremities, with

coalescence and increased redness.

Koplik’s spots usually appear on buccal mucosa 1–2

days before exanthem.

Complications include secondary bacterial infection, oti-

tis media, pneumonia, viral myocarditis, liver function

abnormalities, and thrombocytopenia.

General Considerations

Rubeola is an acute epidemic disease characterized by

marked upper respiratory symptoms and a widespread ery-

thematous maculopapular rash. It is caused by a paramyx-

ovirus transmitted by inhalation of infected droplets. The

severity of the illness varies with the age and immunologic

status of the patient.

Clinical Features

A. Symptoms and Signs—After an incubation period of

7–14 days, a prodrome of high fever develops, associated

with malaise, cough, coryza, and conjunctivitis with photo-

phobia. In 3–5 days, discrete erythematous macules and thin

papules appear on the forehead and behind the ears. Over the

next few days, the lesions spread to the trunk and extremities

(including the palms and soles), coalesce on the face and

upper trunk, and intensify in color to a deeper red. The erup-

tion fades after 5–10 days in the order of its appearance, often

with fine desquamation and postinflammatory hyperpig-

mentation. Koplik’s spots—blue-white pinpoint macules

with a red halo—usually appear on the buccal mucosa 1–2

days before the exanthem and remain for several days. Up to

40% of immunocompromised patients with measles have no

rash; the remainder have either typical or unusual skin find-

ings, including urticarial plaques, petechiae, and palpable

purpura. Rubeola must be distinguished from cutaneous

drug reactions as well as other viral exanthems.

Complications may arise from viral dissemination, sec-

ondary bacterial infection, or hypersensitivity phenomena.

Otitis media, sinusitis, pneumonia, and liver function abnor-

malities are common. Viral myocarditis and thrombocy-

topenic purpura (owing to immune-mediated platelet

destruction) may occur. Death, resulting from pneumonitis

or encephalitis, occurs in about 0.1% of patients in the

CHAPTER 28

628

United States. The complication and case-fatality rates for

the very young, the elderly, the malnourished, and patients

with malignancies or HIV infection are significantly higher.

The clinical presentation in immunocompromised patients

is frequently atypical. One-third of such patients present

with no rash.

B. Laboratory Findings—Serologic studies of paired speci-

mens are the most practical method of confirming the diag-

nosis. Measles virus may be isolated from the blood, urine,

nasopharyngeal washings, and throat or from conjunctival

secretions.

Treatment

Therapy is supportive because no proven antiviral agent is

available. Aerosolized ribavirin may be beneficial for the treat-

ment of measles pneumonitis, but its effectiveness has not yet

been proved. Intravenous immunoglobulin and interferon

are other treatment options for measles pneumonitis and

encephalitis. Isolation precautions must be observed.

Garly ML et al: Prophylactic antibiotics to prevent pneumonia and

other complications after measles: Community-based ran-

domised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in Guinea-

Bissau. Br Med J 2006;333:1245. [PMID: 17060336]

Greenaway C et al: Susceptibility to measles, mumps, and rubella

in newly arrived adult immigrants and refugees. Ann Intern

Med 2007;146:20–4. [PMID: 17200218]

Perry RT, Halsey NA: The clinical significance of measles: A review.

J Infect Dis 2004;189:S4–16. [PMID: 15106083]

Meningococcemia

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Petechial (or, less commonly, urticarial or morbilliform)

rash on the trunk and lower extremities; also on the

palms, soles, and mucous membranes; petechiae are

frequently palpable, with gun-metal gray centers and

irregular borders.

If complicated by purpura fulminans, extensive hemor-

rhagic bullae and areas of necrosis.

Other features of meningococcal meningitis or dissemi-

nated meningococcemia, including meningeal signs,

arthritis, myocarditis, pericarditis, and acute adrenal

infarction; hypotension and shock are often present.

Confirmation of Neisseria meningitidis by culture, Gram

stain, or immunologic tests.

General Considerations

N. meningitidis is a gram-negative diplococcus responsible

for a spectrum of illnesses ranging from a mild upper

respiratory infection to fulminant septicemia. Disease occurs

most often in children under age 15, with the attack rate

highest in infants 6–12 months of age. Peak incidence of

infection is in the winter and spring. Asymptomatic colo-

nization of the nasopharynx is common and provides a

source of person-to-person transmission through infected

droplets. People with deficiencies of the terminal compo-

nents of the complement cascade (C5–9) are particularly

susceptible to invasive and recurrent meningococcal disease.

The cutaneous lesions are a consequence of damage to small

dermal blood vessels both by direct bacterial involvement of

skin vessels and by lipopolysaccharide endotoxins.

Clinical Features

A. Symptoms and Signs—Invasive meningococcal disease

usually results in meningitis or meningococcemia. The incu-

bation period varies from 2–10 days. The onset may be

insidious, following a flulike illness, or abrupt, with fever,

chills, malaise, signs of meningeal irritation, prostration,

and shock. A rash that is characteristically petechial or, less

commonly, urticarial or morbilliform is often among the

earliest signs of generalized infection. The petechiae typi-

cally appear on the trunk and lower extremities but also can

be found on the palms, soles, and mucous membranes. They

are frequently palpable, with gun-metal-gray centers and

irregular borders.

Extensive hemorrhagic bullae and areas of necrosis

develop in patients with meningococcemia whose disease

is complicated by purpura fulminans. Obtundation,

hypotension, and death may ensue within hours despite

appropriate antimicrobial therapy. Absence of meningeal

signs is a feature of this acute fulminant form of meningo-

coccal disease. Children under age 2 have the highest mor-

tality rate, perhaps as a consequence of immaturity of the

protein C system.

Other complications of invasive meningococcal disease

are arthritis, myocarditis, pericarditis, cervicitis, and

Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome. More rare meningo-

coccal diseases include occult bacteremia and chronic

meningococcemia.

B. Laboratory Findings—Confirmation of the diagnosis

depends on demonstration of the organism. This

may be by culture, Gram stain, or immunologic tests.

Blood and cerebrospinal fluid cultures are indicated in

all patients suspected of having invasive disease. Naso-

pharyngeal and synovial cultures are positive in some cases.

Counterimmunoelectrophoresis or latex agglutination with

group-specific antisera of cerebrospinal fluid, urine, or tears

can facilitate rapid diagnosis. A Gram stain of material from

purpuric lesions may reveal the organism. Other laboratory

studies are otherwise nonspecific but should be performed

as indicated to assess and monitor the illness, including eval-

uation for DIC.

DERMATOLOGIC PROBLEMS IN THE INTENSIVE CARE UNIT

629

Differential Diagnosis

Meningococcal infection must be considered in patients

with the combination of fever and a petechial rash, espe-

cially in association with meningitis. Depending on the

clinical presentation, other infections, such as gram-negative

septicemia, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, echovirus and

coxsackievirus infections, and atypical measles, must be

excluded. Vasculitis and other causes of purpura also are

diagnostic possibilities.

Treatment

Intravenous penicillin G or ampicillin is the therapy of choice.

Ceftriaxone is an acceptable alternative (see Chapter 15).

Hemodynamic and other supportive measures must be pro-

vided as necessary to maintain organ system function.

Respiratory isolation is mandatory. Close contacts of patients

with meningococcal disease should be given rifampin pro-

phylaxis and monitored closely.

Ramos-e-Silva M, Pereira AL: Life-threatening eruptions due to

infectious agents. Clin Dermatol 2005;23:148–56. [PMID:

15802208]

Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Potential exposure to ticks in endemic area.

After incubation period of 1–14 days, sudden onset of

fever, headache, myalgia, and nausea or vomiting.

Appearance on days 2–4 of blanchable pinkish red mac-

ular rash over ankles, wrists, and forearms, spreading to

involve the soles, palms, extremities, trunk, and face

within hours; bilaterally symmetric petechiae of the

palms and soles are a major finding.

May be complicated by CNS, cardiac, pulmonary, renal,

or other organ involvement; DIC and shock leading to

death may occur.

Diagnosis can be confirmed by serologic tests, but these

are not reliable before the second week of illness.

General Considerations

Rocky Mountain spotted fever is an acute systemic illness

characterized by fever and a purpuric eruption. The disease

is transmitted to humans by the bite of a tick infected with

the causative organism Rickettsia rickettsii. Transmission

reflects the tick season in a particular geographic area, with

highest incidence in spring and summer. The disease is wide-

spread in the United States and Canada; most cases are from

the southeastern and Rocky Mountain states. All age groups

are affected, but most are between 5 and 9 years old.

Clinical Features

The incubation period is usually about 1 week, ranging from

1–14 days.

A. Symptoms and Signs—Sudden onset of fever, headache,

myalgia, and nausea or vomiting are initial features. On the sec-

ond to fourth days of illness, a blanchable pinkish red macular

rash appears over the ankles, wrists, and forearms, spreading to

involve the soles, palms, extremities, trunk, and face within

hours. Over the next 1–2 days, the eruption becomes papular

and nonblanchable (purpuric) and may evolve into gangrene

of the digits, nose, earlobes, scrotum, or vulva. Bilaterally sym-

metric petechiae of the palms and soles is a major finding. The

illness can persist up to 3 weeks and may be complicated by

CNS, cardiac, pulmonary, renal, or other organ involvement.

DIC and shock leading to death may occur.

B. Laboratory Findings—The diagnosis of Rocky Mountain

spotted fever can be established retrospectively by one of

many serologic techniques, including complement fixation,

latex agglutination, or microagglutination tests. However,

these tests are not reliably positive before the second week of

the illness.

Skin biopsy reveals a necrotizing vasculitis. A Giemsa-

stained smear of tissue sections occasionally may demon-

strate the organism. Immunofluorescent microscopic

examination of skin biopsy specimens may confirm the diag-

nosis as early as the fourth day of illness.

Differential Diagnosis

Rocky Mountain spotted fever must be differentiated from

other serious febrile illnesses such as viral and bacterial

meningitis, meningococcemia, measles, vasculitis, and

thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura.

Treatment

Treatment should be initiated as soon as the diagnosis is sus-

pected. Doxycycline is the drug of choice for patients with

Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Gangrene of the earlobes,

digits, nose, etc. requires additional antibiotics if secondarily

infected.

Chapman AS et al: Diagnosis and management of tickborne

rickettsial diseases: Rocky Mountain spotted fever, ehrli-

chioses, and anaplasmosis—United States: A practical

guide for physicians and other health-care and public

health professionals. MMWR Recomm Rep 2006;55:1–27.

[PMID: 16572105]

Cunha BA. Clinical features of Rocky Mountain spotted fever.

Lancet Infect Dis 2008;8:143–4. [PMID: 18291332]

Dantas-Torres F. Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Lancet Infect Dis

2007;7:724–32. [PMID: 17961858]

CHAPTER 28

630

Necrotizing Fasciitis

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Typically occurs following surgery or penetrating

trauma; diabetes may be a predisposing condition.

Erythema, edema, and pain develop 1–2 days following

surgery or trauma with central areas of dusky gray-blue

discoloration, occasionally in association with serosan-

guineous blisters.

Involved areas become gangrenous within a few days;

culture frequently grows multiple aerobic and anaero-

bic bacteria.

Severe systemic toxicity is usually present.

General Considerations

Necrotizing fasciitis is a rare, life-threatening soft tissue

infection characterized by acute and widespread fascial

necrosis. It typically occurs following surgery or penetrating

trauma. Diabetes may be a predisposing condition. The

pathogenesis involves the introduction of organisms into the

subcutis with subsequent spread through fascial planes.

Many different virulent bacteria have been isolated in associ-

ation with necrotizing fasciitis, including β-hemolytic strep-

tococci, staphylococci, coliforms, enterococci, Pseudomonas,

and Bacteroides. Rhizopus and C. albicans have been cultured

from tissue. The process is often fatal unless diagnosed

quickly and treated aggressively.

Clinical Features

A. Symptoms and Signs—Erythema, edema, and pain

develop 1–2 days following introduction of the organism into

the subcutis. The infection spreads rapidly and deeply, result-

ing in local tissue ischemia. Clinically, there are central areas of

dusky gray-blue discoloration, occasionally in association with

serosanguineous blisters. Crepitus is usually absent in necro-

tizing fasciitis. Within a few days, these areas become gan-

grenous; liberation of toxins and organisms into the

bloodstream leads to severe systemic toxicity. The extremities

are the most commonly affected site, but the trunk, perineum,

and abdomen also may be affected. Fournier’s gangrene is

necrotizing fasciitis of the perineum, scrotum, or penis that

spreads rapidly to the anterior abdominal wall. Necrotizing

fasciitis may be confused with cellulitis, angioedema,

eosinophilic fasciitis, and clostridial myonecrosis.

B. Laboratory Findings—Incisional biopsy of both the

advancing edge and the involved tissue should be performed

early, looking for necrotic fascia and the causative organism.

Tissue cultures frequently grow multiple aerobic and anaer-

obic bacteria as well as fungi. Radiographs of soft tissue

rarely may reveal tissue gas.

Treatment

Radical surgical debridement, intravenous broad-spectrum

antibiotics, and general supportive care are the mainstays of

therapy. The major indication for operative treatment is fasciitis

spreading despite empirical antibiotics in an acutely ill patient.

Anaya DA, Dellinger EP: Necrotizing soft-tissue infection:

Diagnosis and management. Clin Infect Dis 2007;44:705–10.

[PMID: 17278065]

Gabillot-Carre M, Roujeau JC: Acute bacterial skin infections and

cellulitis. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2007;20:118–23. [PMID:

17496568]

Lopez FA, Lartchenko S: Skin and soft tissue infections. Infect Dis

Clin North Am 2006;20:759–72. [PMID: 17118289]

Mehta S et al: Morbidity and mortality of patients with invasive

group A streptococcal infections admitted to the ICU. Chest

2006;130:1679–86. [PMID: 17166982]

Miller LG et al: Necrotizing fasciitis caused by community-

associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Los

Angeles. N Engl J Med 2005;352:1445–53. [PMID: 15814880]

Toxic Shock Syndrome (TSS)

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Highest incidence in menstruating women, persons

with focal staphylococcal infection or colonization, and

women using a diaphragm or contraceptive sponge—

but may occur in others.

Rapid onset of fever, vomiting, watery diarrhea, sore

throat, and profound myalgias, with hypotension.

Diffuse, blanching erythema appears early, predomi-

nantly truncal, with accentuation in the axillary and

inguinal folds and spreading to the extremities; desqua-

mation of the involved skin and of the palms and soles

seen during the second or third week.

Acute renal failure, acute respiratory distress syndrome

(ARDS) , refractory shock, ventricular arrhythmias, and DIC

may occur.

General Considerations

Toxic shock syndrome is a multisystem illness characterized

by the acute onset of high fever associated with myalgias,

vomiting, diarrhea, headache, pharyngitis, and hypotension.

Mucocutaneous findings are prominent. Staphylococcal pyo-

genic toxin superantigens (TSST-1) and enterotoxins B and

C are involved in the pathogenesis. Streptococcal toxic shock

syndrome is caused mainly by toxin-producing group A

strains but also by strains of groups B, C, F, and G. In the

1980s, most cases occurred in menstruating women using

superabsorbent tampons. Currently, most cases are caused

by nonmenstrual S. aureus infection—postoperative,

DERMATOLOGIC PROBLEMS IN THE INTENSIVE CARE UNIT

631

influenza-associated, or recalcitrant erythematous desqua-

mating syndrome—or by colonization of contraceptive

diaphragms or sponges. Streptococcal toxic shock syn-

drome may or may not be associated with necrotizing fasci-

itis or myositis.

Clinical Features

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) case

definition of toxic shock syndrome is based on six major

criteria—high fever, rash, desquamation, hypotension,

involvement of three or more organ systems (eg, GI, muscu-

lar, mucous membrane, renal, hepatic, hematologic, and

CNS)—and exclusion of other causes.

A. Symptoms and Signs—Patients usually present with

rapid onset of fever, vomiting, watery diarrhea, sore throat,

and profound myalgias. Significant hypotension develops

during the first 48–72 hours of illness. Multisystem organ

involvement probably results both from poor tissue perfu-

sion and from toxin-induced damage. Potentially devastating

complications include acute renal failure, ARDS with pul-

monary edema, refractory shock, ventricular arrhythmia,

and DIC. Some patients have relatively mild episodes.

The cutaneous and mucous membrane findings are

prominent but not diagnostic. A diffuse, blanching erythema

(scarlatiniform exanthem) appears early. The rash is pre-

dominantly truncal, with accentuation in the axillary and

inguinal folds and spreading to the extremities. Erythema

and edema of the palms and soles may develop. Generalized

nonpitting edema is also common. Intense hyperemia of the

conjunctival, oropharyngeal, and vaginal surfaces is a fre-

quent finding. Desquamation of the involved skin and of the

palms and soles is seen during the second or third week of ill-

ness. Toxic shock syndrome recurs in approximately 30% of

untreated patients. Mortality is higher (12%) in patients with

nonmenstrual causation.

B. Laboratory Findings—Laboratory studies are useful for

assessing and monitoring the severity and progression of the

illness. Patients often have leukocytosis with a left shift and

thrombocytopenia. If DIC is suspected, coagulation studies

should be obtained. Serum electrolytes, calcium, phospho-

rus, creatine kinase, renal function and liver function tests,

albumin, total serum protein, and amylase may be abnormal.

Urinalysis may show proteinuria and pyuria.

Chest x-ray, arterial blood gas determinations, and

echocardiography may provide useful information. Cultures

of blood, soft tissue sites of infection, and all mucosal surfaces

(including the trachea if intubation is performed) should be

obtained. Serologic tests should be ordered for Rocky

Mountain spotted fever, leptospirosis, or measles, as indicated

in individual patients, to exclude alternative diagnoses.

Differential Diagnosis

Toxic shock syndrome is a clinical diagnosis. Appropriate

laboratory tests help to distinguish it from several serious

and potentially life-threatening exanthematous diseases,

including streptococcal toxic shock–like disease, scarlet fever,

Kawasaki’s disease, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, SJS, drug

eruptions, bacterial sepsis, measles, and leptospirosis.

Treatment

Tampons or other contraceptive devices must be removed

immediately, followed by irrigation of the vagina. Any surgi-

cal packings also should be removed. Soft tissue abscesses,

empyema, and other sites of infection require surgical

drainage and irrigation.

An antistaphylococcal antibiotic should be administered

intravenously based on a presumptive diagnosis, although its

effect on the outcome of the acute episode is unclear.

Antibiotics do reduce the recurrence of menses-related toxic

shock syndrome. Treatment of group A streptococcal toxic

shock syndrome includes penicillin or ceftriaxone plus clin-

damycin or erythromycin.

Supportive care, including management of organ system

failure and treatment of hypotension, is the mainstay of ther-

apy. Systemic corticosteroids, if given within 3–4 days of dis-

ease, reduce its severity and shorten the duration of fever.

Andrews MM et al: Recurrent nonmenstrual toxic shock syn-

drome: Clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and treatment. Clin

Infect Dis 2001;32:1470–9. [PMID: 11317249]

Kain KC, Schulzer M, Chow AW: Clinical spectrum of nonmen-

strual toxic shock syndrome (TSS): Comparison with menstrual

TSS by multivariate discriminant analyses. Clin Infect Dis

1993;16:100–6. [PMID: 8448283]

Ramos-e-Silva M, Pereira AL: Life-threatening eruptions due to

infectious agents. Clin Dermatol 2005;23:148–56. [PMID:

15802208]

REFERENCES

James WD, Berger T, Elston D (eds): Andrew’s Diseases of the Skin:

Clinical Dermatology, 10th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2006.

Habif TP: Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and

Therapy, 4th ed. St. Louis: Mosby, 2004.

Lebwohl M et al: Treatment of Skin Disease: Comprehensive

Therapeutic Strategies, 2d ed. St. Louis: Mosby, 2006.

Provost TT, Flynn JA (ed): Cutaneous Medicine. New York: BC

Decker, 2002.

Wolff K et al (eds): Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine,

7th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2008.

632

00

The critical care of patient with peripheral vascular disease

requires considerable diagnostic skill and clinical acumen.

Associated medical comorbidities—diabetes, renal insuffi-

ciency, coronary artery disease, and many others—necessitate

admission to an ICU for preoperative optimization and post-

operative observation. Acute arterial occlusion, pulmonary

embolism, and—with the advent of endovascular interven-

tions—pseudoaneurysm formation are among the more

common vascular-related complications encountered in the

otherwise routine care of medical and surgical patients.

This chapter addresses acute vascular emergencies in criti-

cally ill patients and discusses the management of complica-

tions following both elective and emergency vascular surgical

procedures.

VASCULAR EMERGENCIES IN THE ICU

Acute Arterial Insufficiency

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

The “six Ps”: pain, paralysis, paresthesia, pallor, pulse-

lessness, and poikilothermia.

Loss of light touch and position sense followed by

paralysis.

Absence of previously palpable distal pulses and slow

capillary refill.

Cool extremity with skin mottling, often with a detectable

line of demarcation.

Collapse of the superficial venous system and develop-

ment of venous thrombosis and rigid muscular com-

partments in prolonged ischemia.

General Considerations

The management of acute limb ischemia continues to chal-

lenge today’s critical care specialist. Patients often present in a

severely compromised state with unclear symptomatology and

may have multiple associated medical illnesses. Despite

improved therapeutic options in recent years, outcome

remains poor. In a review of 35 reported series, a mortality rate

of 26% and an amputation rate of 37% were documented.

Decreased arterial inflow in a previously normal limb

may be due to embolization from a remote origin (owing to

in situ thrombosis from preexisting occlusive disease) or may

occur in association with a low-flow state. Although throm-

bosis occurs more frequently than embolic occlusion in the

general population, progression to complete occlusion of an

atherosclerotic thrombus is an unusual cause of acute arterial

insufficiency in a critically ill patient admitted for other rea-

sons. Depending on the artery affected and the adequacy of

collateral circulation, clinical presentation may be along a

continuum from subtle to overt limb threat.

The most common site of origin of an embolus is the

heart, with atherosclerotic disease the predominant under-

lying factor. Other sources include aortic and peripheral

aneurysms, atherosclerotic debris from ulcerating plaques,

and less commonly, paradoxical embolus through a cardiac

anomaly, arteritis, or vascular trauma. Atrial fibrillation,

often seen in the postoperative setting, is currently associ-

ated with two-thirds to three-quarters of peripheral emboli.

Acute arterial insufficiency in the ICU is most commonly

caused by intrinsic obstruction produced by the emboliza-

tion of clot from distant sites. Atherosclerotic cardiac vascu-

lar disease accounts for 60–70% of all arterial emboli. Most

arise in patients with atrial fibrillation and stasis in the left

atrial appendage. Those who have sustained a recent myocar-

dial infarction also may develop mural thrombi, most com-

monly at the cardiac apex or in a trabeculation of the left

ventricle. No clear temporal relationship exists between the

time of the myocardial infarction and when embolization

29

Critical Care of Vascular

Disease & Emergencies

James T. Lee, MD

Frederic S. Bongard, MD

Copyright © 2008 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. Click here for terms of use.

CRITICAL CARE OF VASCULAR DISEASE & EMERGENCIES

633

occurs. When congestive heart failure or cardiomyopathy is

present, dyskinetic segments again result in areas of relative

stasis that lead to the formation of thrombi. After separation

from its site of origin, an embolus may be swept into the

innominate or left subclavian artery and travel distally in an

upper extremity until the arterial tree narrows sufficiently to

trap it. If it is carried into either of the internal carotid or ver-

tebral arteries, a bland (dry) stroke results. Distal emboli typ-

ically lodge where vessels taper or branch and consequently

are seen in the superior mesenteric artery, resulting in vis-

ceral ischemia, or in the iliac, femoral, or popliteal arteries.

Peripheral emboli travel to the lower extremities 10 times

more often than to the upper extremities. Commonly

involved arterial segments are listed in Table 29-1.

Other intrinsic sources of arterial emboli are atheroscle-

rotic debris from aneurysms, fibrin plugs, or collections of

platelets. It is unusual for atherosclerotic emboli to present

de novo in a patient admitted to the ICU for another reason.

The exception to this is the blue toe syndrome, which results

from occlusion of digital vessels by atherosclerotic emboli.

However, when the possibility of an expanding aneurysm or

symptomatic chronic aortic dissection was the reason for

admission, acute limb ischemia should arouse concern that

the atherosclerotic plaque or the grumous clot lining the

aneurysm has embolized.

Patients with atherosclerotic microemboli frequently

have transient focal ischemia associated with minor tissue

loss. The clinical distinction between arterial embolism and

arterial thrombosis is often difficult to make, although an

effort should be made to confirm the diagnosis because of

the differences in therapeutic approach and outcome

(Table 29–2). Fibrin plugs and platelet emboli occur most

commonly in patients with disseminated intravascular coag-

ulation (DIC) or in those anticoagulated with heparin who

develop antiheparin antibodies.

Extrinsic emboli are produced when foreign material

such as catheter tips, balloon fragments, and endovascular

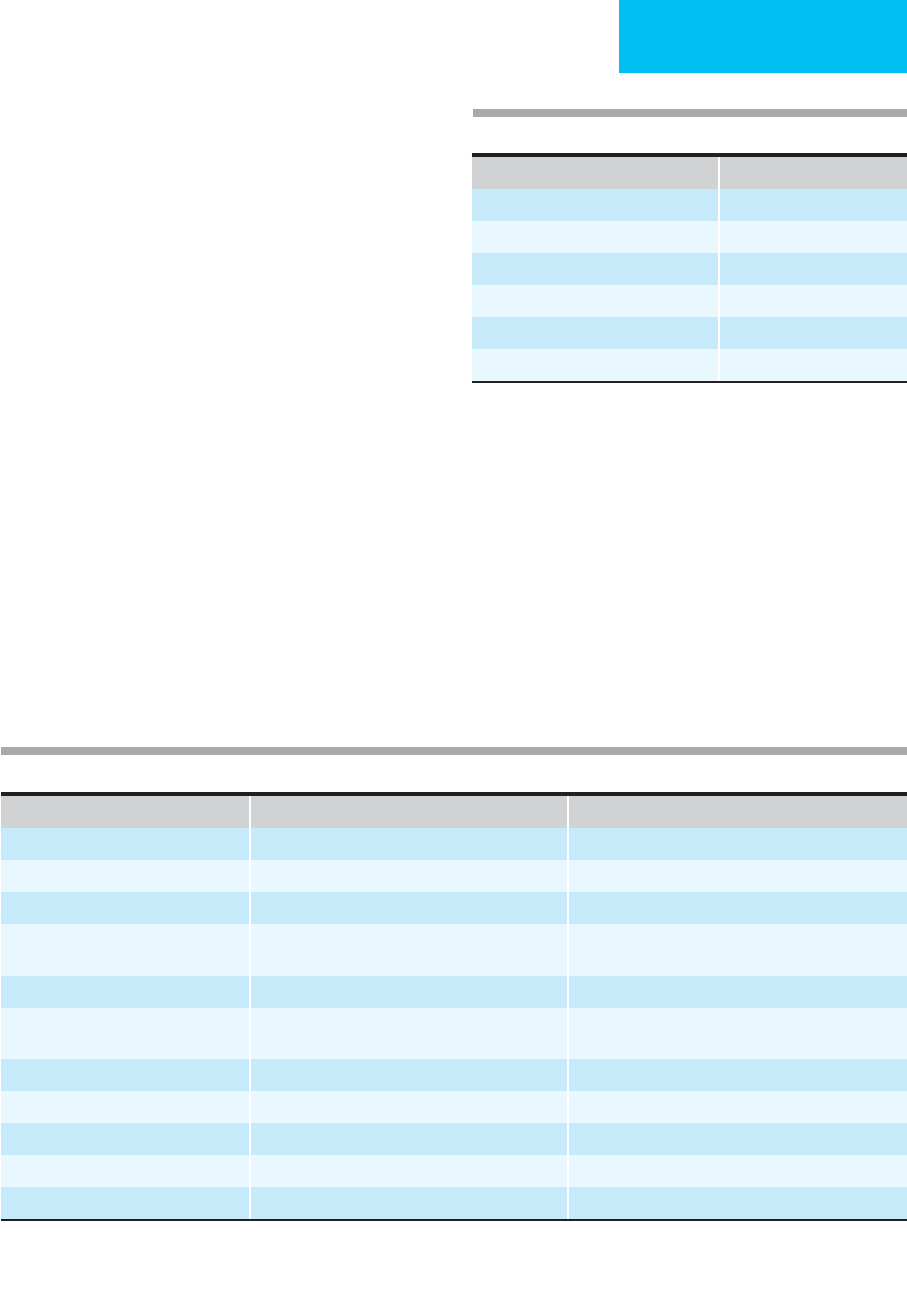

Characterisitics of Occlusion Embolus Thrombosis

Onset of symptons Rapid or immediate Slower or insidious

Prior symptoms: claudication Rare Frequent

Length of time to presentation Acute Chronic

Identifiable source Recent cardiac disease (eg, atrial fibrillation,

myocardial infarction)

None

Physical findings Normal contralateral extremity Bilateral peripheral vascular disease

Angiography Multiple sharp cutoffs, “reversed meniscus,” scant

collaterals

Diffuse peripheral vascular disease, irregular cutoff,

many collaterals

Goal of immediate therapy Eliminate embolus Correct disease

Long-term pharmacologic treatment Anticoagulation Platelet inhibition

Results of thromboembolectomy Good Poor

Amputation risk Lower Higher

Causes of mortality Cardiac disease Limb ischemia

Adapted from Young JR et al (eds): Peripheral Vascular Disease. St Louis: Mosby–Year Book, 1991; and from Rutherford RB (ed): Vascular

Surgery. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2000.

Table 29–2. Differentiation of emoblism from thrombosis.

Table 29–1. Sites of peripheral arterial emboli.

Segment Incidence (%)

Femoral 36

Aortoiliac 22

Popliteal-tibial 15

Upper extremity 14

Visceral 7

Other 6

Data complied from 1303 embolic events at the Massachusetts

General Hospital and Stanford University. Adapted from Rutherford RB

(editor): Vascular Surgery. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2000.

CHAPTER 29

634

occluding devices migrate to distant sites. Bullet emboli

should be remembered as a possible cause of acute arterial

insufficiency in a trauma victim in whom the missile was not

recovered or was unreachable at the time of surgery. Other

penetrating injuries, such as stab wounds, may partially dis-

rupt the vascular intima and begin the process of dissection

and thrombotic occlusion.

Once arterial flow is halted, three pathophysiologic events

occur, each worsening the overall ischemic insult. Initially,

propagation of thrombus can occlude potential collateral

vessel orifices and lend to the no-reflow phenomenon once

large vessel revascularization is established. Second, cellular

swelling owing to local hypoxia may cause red blood cell

trapping and effectively increase the ischemic period even

after adequate inflow is restored. The cause of cellular

swelling is debated but may consist of failure of the sodium

pump. This inability to reperfuse after ischemic intervals is

termed the no-reflow or low-reflow phenomenon. As fluid

leaves the interstitium and enters the cellular matrix, the

effective viscosity of the blood increases, raising the pressure

required to overcome the blood’s inertia (yield stress) and

causing significant narrowing and occlusion of the arterioles,

capillaries, and venules. The more protracted the ischemic

period, the greater is the fluid loss and the higher is the yield

stress. Muscle damage produced by ischemia and reperfusion

is more related to “reflow” than to the absolute period of

ischemia. Animal models have shown that graded return of

inflow over a period of time did result in improved postis-

chemic muscle function and less edema. The mediators of

capillary endothelial injury are highly active oxygen metabo-

lites such as superoxide (O

2

–

) and hydroxyl (-OH) radicals.

On reperfusion, the lactic acid, potassium, myoglobin, and

cardiodepressants such as thromboxane that have accumu-

lated in the ischemic limb are systemically released. The

resulting metabolic acidosis and biochemical insult can have

profound consequences in an already fragile patient.

Peripheral nerve fibers that mediate light touch and posi-

tion sense are much more vulnerable than skin and subcuta-

neous tissue. Thus deficits in these areas, although subtle,

present an illusion of surface viability while masking the

presence of complete functional loss.

Clinical Features

A. Symptoms and Signs—Acute ischemia is often mani-

fested by some or all of the six cardinal signs known as the

“six P’s.” Ischemic pain is profound, and most patients

require large doses of opioid analgesics before they obtain

relief. The diagnosis of acute arterial ischemia is usually

entertained because of the localized nature of the pain. The

level of the obstruction is typically in the artery lying one

joint above the area of discomfort (Table 29–3). Emboli to

the axillary artery, which has excellent collateral flow, are

either asymptomatic, detected primarily by a pulse deficit,

or noted only with physical activity. Conversely, emboli to

the common femoral or popliteal arteries typically produce

profound ischemia, and symptoms appear rapidly. On exam-

ination, the extremity is pallid and cool. Unlike venous

thrombosis, arterial ischemia produces a white rather than a

violaceous limb. Occasionally, the sensorial perception of

numbness and paresthesias predominates and may mask the

primary component of pain. A late sign, paralysis is the result

of motor nerve ischemia followed by muscle necrosis. Distal

pulses are usually absent, although profound ischemia may

occur in the presence of a normal pulse when the embolus is

lodged distally in the small arteries of the hand or foot. In

some patients—especially those with chronic disease and

generalized edema or anasarca—pulses may be difficult or

impossible to detect. The extremity may be firm because of

muscle swelling. A compartment syndrome occurs when

muscle swelling limits venous outflow from within a fascial

compartment. An indurated and hard compartment is an

indication for release of the pressure by fasciotomy.

Although indicative of arterial insufficiency, these symp-

toms are in essence nonspecific. They serve to alert the clini-

cian to the presence of ischemia but do not lend themselves

to grading or quantification. It is of paramount importance

to assess the degree of ischemia, which is stratified into three

categories based on the physical findings: viable, threatened,

and irreversible. Symptoms depend on the location of the

embolus and the adequacy of the collateral circulation. The

Joint Council of the Society for Vascular Surgery and the

North American Chapter of the International Society for

Cardiovascular Surgery has developed a consensus that

divides severity of limb ischemia into three categories

(Table 29–4). Category I (viable) limbs usually present as an

acute on chronic process. Patients in this category have abun-

dant collaterals and develop an acute femoral artery throm-

bosis overlying a chronic stenosis. The prognosis of category

II patients is dictated by the time interval between diagnosis

and revascularization. Prompt versus immediate intervention

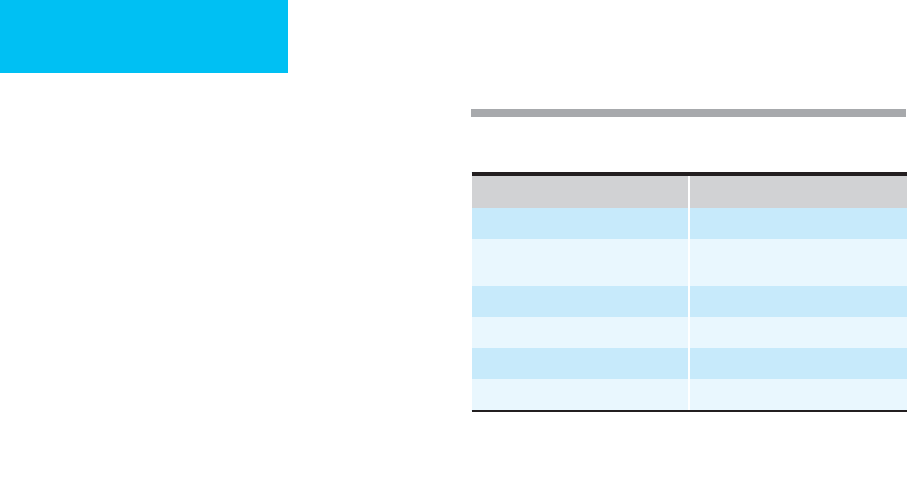

Site of Occlusion Line of Demarcation

Infrarenal aorta Mid abdomen

Aortic bifurcation and common

iliac arteries

Groin/pelvis

External iliac arteries Proximal thigh

Common femoral artery Lower third of thigh

Superficial femoral artery Upper third of calf

Popliteal artery Lower third of calf

Adapted from Way LW (editor): Current Surgical Diagnosis and

Treatment, 10th ed. Originally published by Appleton & Lange.

Copyright © 1994 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc.

Table 29–3. Demarcation of physical findings in relation

to site of arterial occlusion.

CRITICAL CARE OF VASCULAR DISEASE & EMERGENCIES

635

is dictated by the severity of presentation. Amputation is the

only recourse in category III patients.

B. Noninvasive Diagnostic Studies

1. Doppler examination—A Doppler flow probe is useful

in patients who are edematous or in whom a pulse may

not be detectable for other reasons. Evidence of flow by

Doppler examination indicates only that obstruction is not

complete—it does not mean that flow is adequate. One should

guard against grading “Doppler pulses” because they are

influenced by several factors, including the angle of

insonation, the gain of the system, and the flow in the artery.

The more superficial the vessel under consideration, the

higher is the frequency of the probe that should be used.

2. Ankle-brachial index (ABI)—Although used primarily

in patients with chronic arterial disease, the ABI may be use-

ful in patients who complain of subtle changes in their

extremities. The ABI is also useful in postoperative vascular

patients for monitoring graft patency. The index is calculated

by placing a blood pressure cuff at the high calf position, just

below the knee, where it will occlude the tibial arteries. A

Doppler probe is placed over either the posterior tibial or the

dorsalis pedis artery, and the cuff is then deflated. The pres-

sure at which flow resumes is documented to obtain an

opening pressure. The brachial artery pressure is measured in

a similar manner, taking the arm with the higher systolic

pressure. The ankle-brachial index then is calculated (by

dividing ankle Doppler pressure by brachial Doppler pres-

sure). An index greater than 1.0 is normal, and an index less

than 0.4 signifies a threat to the limb. Of greatest value are

changes in the index from previous values or a discrepancy

between the two extremities.

3. Duplex scanning—In equivocal cases or when angiogra-

phy is not available, noninvasive color-flow duplex ultra-

sonography has been a major advance in the diagnosis and

treatment of vascular diseases. It has several components. A

two-dimensional real-time image is projected in the B mode,

which can locate vessels in soft tissues, measure vessel

diameters, and reveal irregularities within the lumen. This

may be helpful in locating the position of the embolus.

Pulsed-wave Doppler technology determines the velocity of

blood flow at a specified location that is superimposed on the

B-mode image. Turbulent flow is seen with a mosaic pattern,

whereas a color-flow void signifies occlusion. Although

duplex scanning can be performed conveniently at the bed-

side, it has the disadvantage of being highly operator-

dependent. Duplex scanning can provide essentially the same

information as arteriography with respect to localization of

arterial segments with either stenosis or total occlusion.

4. Air plethysmography—Although it is seldom used, air

plethysmography remains a valuable noninvasive diagnostic

technique. Several types are available, but all measure the

same physiologic parameter: change in volume. A blood

pressure cuff is placed around the affected extremity and

inflated to 65 mm Hg. A pressure waveform tracing is then

recorded, and occlusive disease is graded based on pulse con-

tour. An advantage of this application is that the recording

obtained is not affected by vessel wall stiffness. In conjunc-

tion with segmental pressure measurements, an accurate

assessment in patients with peripheral occlusive disease can

be made. However, in the setting of acute limb ischemia,

other more specific modalities are necessary.

C. Angiography—Radiographic studies are best obtained in

consultation with a vascular surgeon to avoid unnecessary

delays. Arteriography remains the standard and is extremely

useful in the planning of operative procedures and is recom-

mended in all but the most straightforward cases. Only when

the location of the occlusion is apparent (eg, femoral embolus)

and coupled with an acutely ischemic limb is preoperative

angiography required. However, when symptoms are atypi-

cal in a threatened limb, arteriography is helpful in deter-

mining the surgical strategy or in the institution of

catheter-directed thrombolytic therapy. The major disadvan-

tage of radiologic studies in this setting is the time required

to obtain them. Delayed can lead to irreversible soft tissue

ischemic injury.

Category Description Sensory Loss Muscle Weakness Arterial Doppler Venous Doppler

I. Viable

II. Threatened

Marginal

Immediate

III. Irreversible

No immediate threat

Salvage with prompt treatment

Salvage with immediate treatment

Permanent tissue loss

None

Minimal

Rest pain

Anesthetic

None

None

Mild to moderate

Paralysis

+

–

–

–

+

+

+

–

Adapted from Rutherford RB et al: Recommended standards for reports dealing with lower extremity ischemia: Revised version.

J Vasc Surg 1997;26:517.

Table 29–4. Clinical categories of acute limb ischemia.

CHAPTER 29

636

Differential Diagnosis

Acute arterial insufficiency owing to an embolus may be

mimicked by low-flow states produced by congestive heart

failure and hypovolemic shock. In the latter conditions, how-

ever, global ischemia is present, and the localizing symptoms

associated with an embolus are lacking. Acute stroke or tran-

sient ischemic attacks may produce muscle weakness but are

seldom associated with pain. Aneurysmal disease or aortic

dissection not only may be the source of emboli but also may

result in rupture. If a dissection extends distally, it may

become thrombotic, producing acute ischemia of the organs

that receive blood from its false channel. Diabetic neuropa-

thy and neuritis may produce hypesthesias in the extremities

but seldom are a diagnostic dilemma.

Treatment

Prompt restoration of inflow is the most important manage-

ment priority. In general, the extent of tissue necrosis and the

resulting disability are directly proportional to the duration

of ischemia. Tolerance of ischemia varies widely among dif-

ferent tissues, extremities, and individuals. Thus a safe upper

limit for arterial compromise cannot be established,

although most authorities cite 4–6 hours as the usual time

limit beyond which irreversible injury of muscles and nerves

may have occurred, even though the overlying skin still may

be viable. For this reason, once a threat to limb survival has

been recognized, prompt treatment is paramount.

A. Anticoagulation—Systemic anticoagulation with heparin

is used unless life-threatening contraindications such as active

GI or cerebral bleeding is present. Heparin prevents the distal

propagation of thrombus, protects the distal vascular bed,

and preserves the extremity’s outflow. The usual dose of

heparin is 100 units/kg given as a bolus, followed by 10–20

units/kg per hour. Before heparin is started, one should

record a baseline partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), pro-

thrombin time (PT), and platelet count. Heparin is cleared

when bound to receptors on endothelial cells and macrophages,

where it is depolymerized. Consequently, its half-life depends

on the initial bolus. The half-life increases from approximately

30 minutes following an intravenous bolus of 25 units/kg to

60 minutes with a bolus of 100 units/kg and to 150 minutes

with a bolus of 400 units/kg. Based on the standard dosage,

most authors recommend titrating a continuous heparin drip

to lengthen the aPTT to twice baseline. Heparin should be

started before any diagnostic maneuvers and may be contin-

ued through to the time of surgery. Titration of the heparin

dosage should not substitute for or delay appropriate surgical

management. The use of heparin should be followed by oral

anticoagulation to prevent recurrent embolism in patients

undergoing thromboembolectomy.

Some surgeons recommend nonoperative management

for acute arterial ischemia, in which case heparin in “high”

doses (20,000 units as an IV bolus followed by 4000 units/h)

is used as the sole form of treatment. Extreme caution must

be exercised in recommending such therapy, however, and

only patients without signs of limb threat should be treated

with anticoagulation alone. This therapy is best reserved for

upper extremity lesions in which collateral flow is good—or

in lower extremity cases in patients whose neural function is

not diminished or in whom it improves quickly after institu-

tion of therapy.

B. Rheologic Agents—The increase in blood viscosity asso-

ciated with acute ischemia has led some vascular surgeons to

recommend the use of either mannitol or low-molecular-

weight dextran (dextran 40; MW 40,000) to reduce cellular

swelling. An additional benefit of these agents is that they

produce an osmotic diuresis and may help to prevent renal

failure owing to myoglobin released from ischemic and

necrotic muscle. Mannitol is started with an intravenous

bolus dose of 25–50 g. Care must be exercised in patients

with congestive heart failure because the increased intravas-

cular volume may worsen cardiac symptoms.

C. Platelet-Active Agents—Aspirin, the agent prescribed

most commonly for this purpose, has been thoroughly eval-

uated and found to prevent vascular death by approxi-

mately 15% and nonfatal vascular events by about 30% in a

meta-analysis of over 50 secondary prevention trials in var-

ious groups of patients. The role of aspirin in acute limb

ischemia is more restricted to postoperative adjunctive

cardiac prophylaxis.

Integrin glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor antagonists (eg,

abciximab) inhibit the final common pathway of platelet

aggregation. Their development objective was to prevent

restenosis in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary

intervention. Three large randomized trials involving

approximately 27,000 patients resulted in a higher mortality

and excessive bleeding complications when compared with

aspirin. The role of this class of medications is evolving.

Thienopyridines such as clopidogrel inhibit ADP-induced

platelet aggregation with no direct effects on arachidonic acid

metabolism. Use of this agent in the acute setting has not been

studied; however, in a comparison trial with aspirin involving

a subset of 6400 patients, virtually all the benefit associated

with clopidogrel was observed in the group with symptomatic

peripheral vascular disease. As a group, these patients had

fewer myocardial infarctions and fewer vascular-related

deaths than did the aspirin-treated group. The main disad-

vantage is the permanent platelet defect encountered, which

can be replaced only with platelet turnover.

D. Thrombin Inhibitors—Direct thrombin inhibitors (eg,

lepirudin, desirudin, bivalirudin, and argatroban) have been

used successfully to treat arterial and venous thrombotic com-

plications of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Despite

producing a more predictable anticoagulant response than

heparin, direct thrombin inhibitors have yet to find a place in

the treatment of acute arterial thrombosis. Potential disadvan-

tages include the irreversible nature of this complex, because

no antidote is available if bleeding occurs, and its narrow