Bongard Frederic , Darryl Sue. Diagnosis and Treatment Critical Care

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

DERMATOLOGIC PROBLEMS IN THE INTENSIVE CARE UNIT

617

multiple medications. In general, the interval between initial

dose of the drug and onset of the disease is 1–3 weeks, except

for phenytoin-induced cases, which may occur as late as 8

weeks following the start of therapy. If the patient has a his-

tory of SJS or TEN from previous exposure to a drug, the

time period may be reduced to 24–48 hours. Patients with

AIDS appear to have an increased risk for TEN.

Clinical Features

A. Symptoms and Signs—Fever, nausea, vomiting, diar-

rhea, malaise, headache, upper respiratory symptoms, chest

pain, myalgia and arthralgia, and conjunctivitis usually pre-

cede the skin and mucous membrane lesions by 1–14 days.

Cutaneous involvement appears acutely as tender, discrete,

symmetric erythematous or purpuric macules and urticarial

plaques with atypical target lesions with dusky centers on the

face and upper trunk. Coalescence and extension to the

entire body rapidly ensue. Subsequently, large flaccid bullae

develop within the areas of erythema, and the necrotic epi-

dermis sloughs in sheets. Pressure applied directly over an

intact blister produces lateral spread of the lesion. Gentle

rubbing of erythematous areas induces separation of the epi-

dermis (Nikolsky’s sign). In SJS, the extent of epidermal

detachment is less than 10% of the body surface area. In

TEN, coalescence and extension to the entire body ensue rap-

idly, with detachment of the epidermis exceeding 30% of the

body surface area. The palms and soles may be involved, but

the hairy part of the scalp characteristically is spared.

Mucous membrane involvement is extensive, with erosions

or ulcers of the conjunctiva, lips, oropharynx, trachea,

esophagus, and anogenital area.

The extent of epidermal separation is a major prognostic

factor. Sepsis is the most frequent cause of death and may be

heralded by a sudden drop in temperature. Pulmonary

embolism, pulmonary edema, and GI bleeding are other

important causes of death. Pneumonia superimposed on

sloughing of the tracheobronchial mucosa may require ven-

tilatory assistance. Fluid loss, thermoregulatory impairment,

and increased energy expenditure result from extensive skin

loss, as in burn victims. The mortality rate ranges from

25–75% and is higher in elderly patients. Disabling ocular

sequelae affect up to 50% of survivors. Cutaneous reepithe-

lialization requires 2–3 weeks, whereas the mucous mem-

brane lesions persist longer.

B. Laboratory Findings—Routine laboratory studies

reflect the extent and severity of the disease but are not

specific. There may be evidence of electrolyte depletion

and dehydration. Serum creatinine may be elevated owing

to prerenal azotemia or acute tubular necrosis. Serum

aminotransferase levels often are slightly increased. In vir-

tually all patients, anemia is present; lymphopenia, neu-

tropenia, and thrombocytopenia sometimes are seen and

may indicate a poor prognosis. Biopsy of involved skin

may be very helpful, revealing full-thickness epithelial

necrosis.

Differential Diagnosis

Clinically, TEN and staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome

are quite similar. The latter disorder is caused by an epider-

molytic toxin produced by Staphylococcus aureus. The toxin

produces superficial (subcorneal) skin separation. Nikolsky’s

sign is present, but skin tenderness and mucous membrane

lesions usually are absent. Staphylococcal scalded skin syn-

drome more frequently affects neonates and toddlers, is rare

in adults, and has a much better prognosis than TEN.

Historically, SJS and EM major were considered part of

the same disease group. EM major can be differentiated from

SJS by the presence typical target lesions localized in a sym-

metric acral distribution, low or no fever, and frequent asso-

ciation with HSV infection.

Other differential diagnostic considerations include pem-

phigus vulgaris and other blistering diseases, toxic shock syn-

drome, chemical or thermal burns, and Kawasaki’s disease.

TEN shares many features with—and is considered by some

to be a severe form of—SJS.

Treatment

The principles of therapy are similar to those for major

second-degree burn victims. Ideally, patients should be man-

aged in a burn unit.

A. General Measures—Discontinue the most likely offend-

ing medication, provide pain control as necessary, and attend

to fluids, electrolytes, and nutrition. Aggressive nutritional

support should be started early; nasogastric feeding is pre-

ferred to parenteral nutrition.

B. Infection Control—Prophylactic antibiotics may pro-

mote the emergence of resistant strains of bacteria or

Candida and should be avoided. Obtain blood, urine, and

skin cultures frequently, and start empirical broad-spectrum

antibiotics at the earliest sign of infection. Consider acyclovir

in HIV-infected patients because secondary HSV infection

may be clinically undetectable.

C. Skin and Mucous Membrane Care—Ophthalmologic

consultation is essential to prevent blindness and other ocu-

lar sequelae. Oral hygiene and antisepsis are important.

Intact bullae should be left in place because they provide a

natural dressing. Nonviable, necrotic, and loosely attached

areas of epidermis should be débrided. Apply biologic dress-

ings, such as porcine xenografts and cryopreserved cadaveric

allografts, or synthetic coverings, such as hydrogel dressing

or paraffin gauze, to denuded areas. Silver sulfadiazine must

be avoided in patients suspected of sulfonamide sensitivity.

Current Controversies and Unresolved Issues

Toxic epidermal necrolysis has been considered by some to

be at the most severe end of the spectrum of EM and SJS, but

the two disorders instead may be distinct reactional states

with clinicopathologic similarities. Supporting the latter

view is the observation that the three do not have the same

etiologic spectrum.

CHAPTER 28

618

Although corticosteroids have been used for decades,

recent studies suggest that systemic steroid therapy is more

detrimental than useful in TEN. Claims for a reduction of

morbidity and mortality in response to a large dose of sys-

temic steroids in the first 24–48 hours have not been substan-

tiated, and most authors now suggest that corticosteroids

should not be used. Plasmapheresis, cyclophosphamide,

intravenous immunoglobulin, cyclosporine, and infliximab

likewise have been claimed to be beneficial on the basis of case

reports and uncontrolled studies, but again, there is no proof.

Auquier-Dunant A et al: Correlations between clinical patterns

and causes of erythema multiforme majus, Stevens-Johnson

syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis: Results of an

International Prospective Study. Arch Dermatol

2002;138:1019–24. [PMID: 12164739]

Heymann WR: Toxic epidermal necrolysis 2006. J Am Acad

Dermatol 2006;55:867–9. [PMID: 17052494]

Mittmann N et al: Intravenous immunoglobulin use in patients

with toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens-Johnson syndrome.

Am J Clin Dermatol 2006;7:359–68. [PMID: 17173470]

Pereira FA, Mudgil AV, Rosmarin DM: Toxic epidermal necrolysis.

J Am Acad Dermatol 2007;56:181–200. [PMID: 17224365]

Prins C et al: Treatment of toxic epidermal necrolysis with high-

dose intravenous immunoglobulins: Multicenter retrospective

analysis of 48 consecutive cases. Arch Dermatol 2003;139:

26–32. [PMID: 12533160]

Trent J et al: Use of SCORTEN to accurately predict mortality in

patients with toxic epidermal necrolysis in the United States.

Arch Dermatol 2004;140:890–2. [PMID: 15262712]

Phenytoin Hypersensitivity Syndrome

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

High spiking fever, malaise, and rash 2–3 weeks after

starting phenytoin therapy—or sooner if prior exposure

to drug.

Patchy erythematous rash evolving into extensive pru-

ritic maculopapular rash, occasionally with follicular

papules and pustules.

Exfoliative erythroderma, EM, SJS, or TEN may develop,

especially in those with prior adverse reactions to

phenytoin; edema of palms, soles, and face.

Tender localized or generalized lymphadenopathy; mild

to severe hepatic injury; sometimes conjunctivitis,

pharyngitis, diarrhea, myositis, reversible acute renal

failure, and eosinophilia.

General Considerations

A number of adverse skin reactions, ranging from morbilli-

form eruptions to vasculitis, exfoliative erythroderma, EM,

SJS, and TEN, occur in up to 3–15% of patients receiving

phenytoin. In a small percentage of these patients, a distinc-

tive syndrome occurs, characterized by an extensive rash,

fever, eosinophilia, and hepatic injury. The disorder is

believed to be immune-mediated. All age groups are affected.

The incidence is highest in blacks.

Clinical Features

A. Symptoms and Signs—Onset is usually 2–3 weeks after

initiation of therapy—or within days if prior exposure has

occurred—heralded by high spiking fevers, malaise, and a

rash. The cutaneous eruption is variable. It often begins as

patchy erythema that evolves into an extensive pruritic mac-

ulopapular rash. Some patients have follicular papules and

pustules. The rash may generalize into an exfoliative erythro-

derma. EM, SJS, and TEN may occur, especially in patients

with previous adverse reactions to the drug and in those who

continue to receive the drug after developing signs of hyper-

sensitivity. Erythema and edema of the palms and soles and

prominent facial edema are common. The eruption usually

resolves with desquamation.

Tender localized or generalized lymphadenopathy is a

consistent finding. Virtually all patients with this syndrome

have hepatic injury, which varies from mild and transient to

severe and fulminant, resulting in massive hepatic necrosis.

Hepatosplenomegaly is found in most patients. Other fea-

tures of the syndrome, not uniformly present, are conjunc-

tivitis, pharyngitis, diarrhea, myositis, and reversible acute

renal failure. In general, the signs and symptoms resolve rap-

idly once the medication is discontinued; however, multior-

gan abnormalities may progress even after the phenytoin has

been stopped. Some patients endure a prolonged and com-

plicated course of exacerbations and remissions. The mortal-

ity rate approaches 20% in patients with severe liver damage.

B. Laboratory Findings—Laboratory studies are important

for monitoring the severity and progression of the reaction.

Leukocytosis with eosinophilia (5–50%) is common.

Coombs-negative hemolytic anemia and atypical circulating

lymphocytes may be seen. The degree of elevation in serum

aminotransferases and alkaline phosphatase levels reflects

the severity of liver injury, and renal function may be abnor-

mal. It is of note that the erythrocyte sedimentation rate and

serum complement levels are normal in this disorder.

Differential Diagnosis

Other anticonvulsant medications, particularly phenobarbi-

tal, may cause reactions indistinguishable from phenytoin

hypersensitivity disorder. Infectious mononucleosis may

resemble this syndrome.

Treatment

The medication must be discontinued. Data regarding cross-

reactivity among the anticonvulsants is scanty, but if anti-

convulsant therapy is still necessary, valproic acid or

carbamazepine may be safer alternatives.

DERMATOLOGIC PROBLEMS IN THE INTENSIVE CARE UNIT

619

General supportive care is vital because of the multisys-

tem involvement. Systemic corticosteroids are sometimes

used, but their effectiveness has not been documented.

Arif H et al: Comparison and predictors of rash associated with 15

antiepileptic drugs. Neurology 2007;68:1701–9. [PMID:

17502552]

Gogtay NJ, Bavdekar SB, Kshirsagar NA: Anticonvulsant hypersen-

sitivity syndrome: A review. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2005;4:

571–81. [PMID: 15934861]

Kaminsky A et al. Anticonvulsant hypersensitivity syndrome. Int J

Dermatol 2005;44:594–8. [PMID: 15985033]

Seitz CS et al: Anticonvulsant hypersensitivity syndrome: Cross-

reactivity with tricyclic antidepressant agents. Ann Allergy

Asthma Immunol 2006;97:698–702. [PMID: 17165282]

PURPURA

Purpura results from hemorrhage into the skin or mucous

membranes. Incomplete blanching on pressure is characteris-

tic. Purpuric lesions may be a clue to acutely life-threatening

diseases but are seen in benign conditions as well. An impor-

tant step in evaluating the patient with purpura is to determine

whether the lesions are macular (flat) or palpable.

Nonpalpable purpura, the result of bleeding into the skin

without inflammation, is due to disorders of hemostasis and

vessel wall integrity. In these cases, small petechial hemor-

rhages (<3 mm) occur. Common causative factors are throm-

bocytopenia and disorders of platelet function. Petechiae also

may be a clue to diseases that affect the integrity of blood ves-

sels, for example, scurvy or amyloidosis. In contrast, disorders

of coagulation cause bleeding from larger vessels, producing

ecchymoses (ie, hemorrhagic macules >3 mm). Palpable pur-

pura, the expression of inflammatory damage to the vascula-

ture and consequent extravasation of blood, is the hallmark of

small vessel vasculitis but also may be seen with septic emboli.

Purpura develops occasionally as a secondary manifesta-

tion in an inflammatory dermatosis. For example, macular

drug eruptions or exanthematous infectious diseases such as

measles and scarlet fever can become purpuric as a result of

increased permeability of the blood vessels and extravasation

of red cells into the surrounding tissue. Causes of purpura

are classified arbitrarily in Table 28–4. In this section, leuko-

cytoclastic vasculitis, disseminated intravascular coagulation,

and purpura fulminans are discussed.

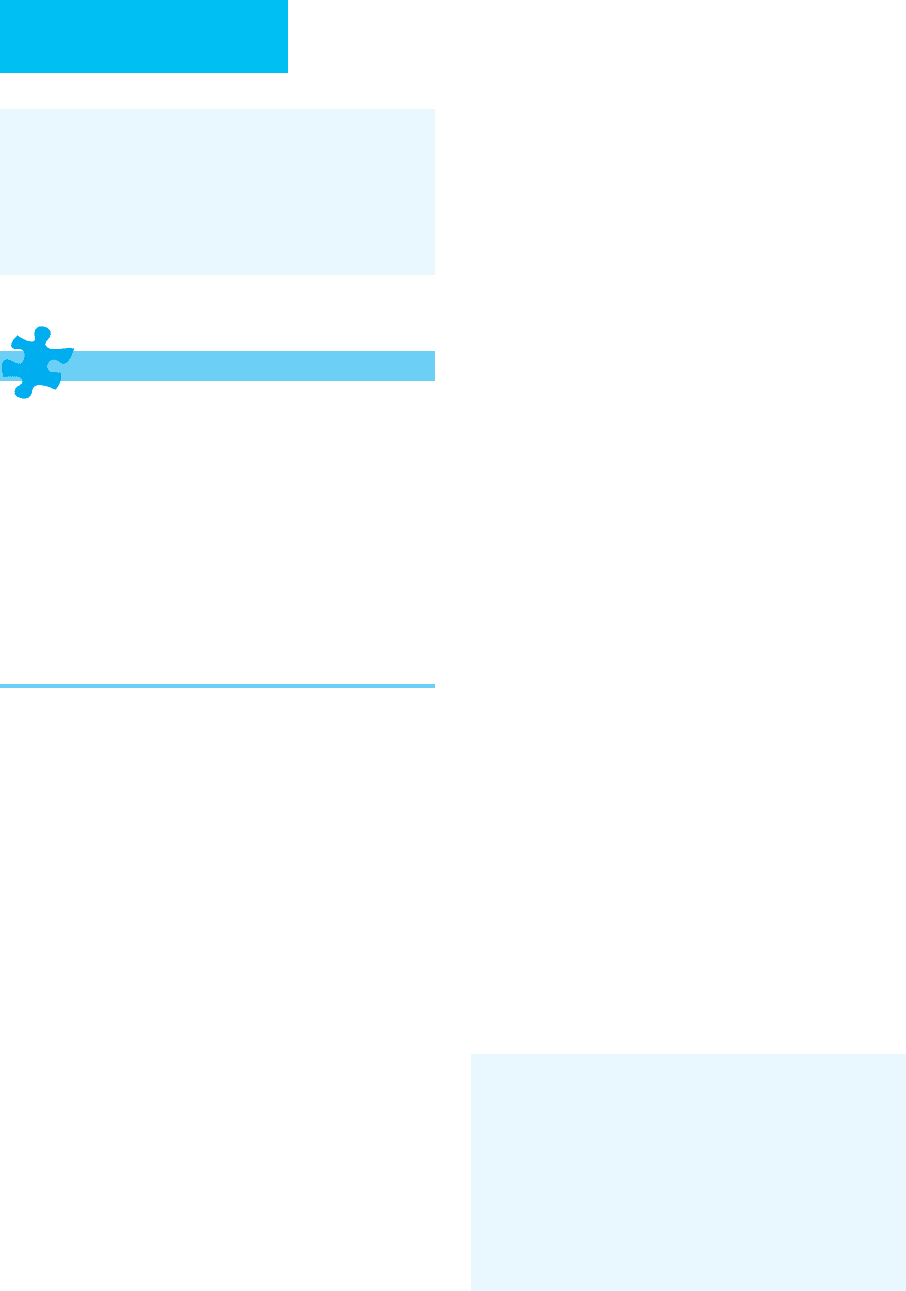

Table 28–4. Causes of purpura.

Vascular Disorders Abnormal distribution

Inflammatory disorders

Diseases associated with splenomegaly

Palpable purpura Kasabach-Merritt syndrome

Vasculitis

Purpura with normal platelet counts

Septic emboli Platelet function defects

Nonpalpable purpura Drugs (eg, salicylates, NSAIDs)

Viral infections Uremia

Rickettsial infections Coagulopathies

Drugs and chemicals

Purpura with high platelet counts

Pigmented purpuric dermatoses Myeloproliferative syndromes

Noninflammatory disorders

Postsplenectomy

Trauma Various neoplasms and inflammatory diseases

Amyloidosis Disorders of Coagulation

Scurvy

Acquired

Dysproteinemic states Vitamin K deficiency

Solar purpura Disseminated intravascular coagulation

Abnormalities of Platelet Number and Function Parenchymal liver disease

Thrombocytopenic purpuras

Cardiopulmonary bypass surgery

Increased platelet destruction Lupus anticoagulant syndrome

Microangiopathic diseases

Inherited

Infections Classic hemophilia

Immunologic disorders von Willebrand’s disease

Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP)

Thrombotic disorders

Drug-induced thrombocytopenia Protein C and S deficiency

Autoimmune diseases (eg, SLE) Antithrombin III deficiency

Decreased platelet production Drugs (eg, aminocaproic acid, estrogen compounds)

Neoplastic replacement of bone marrow Nephrotic syndrome

Myelosuppressive disorders Anticoagulant necrosis

Radiation

Chemotherapy

Infections

CHAPTER 28

620

Leukocytoclastic Vasculitis

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Palpable purpura; hemorrhagic bullae, purpuric

plaques, vesicles, pustules on a purpuric base, and

urticaria-like papules may be present.

Systemic symptoms occur in 40–50%, including fever,

myalgias, and arthralgias; abdominal pain, GI bleeding,

and pulmonary disease (eg, pneumonitis, pleuritis, or

hemoptysis) occur less frequently.

Biopsy of involved skin shows necrotizing vasculitis

with prominent neutrophilic infiltrates in and around

the vessel walls, extravasated red blood cells, and dep-

osition of fibrin.

General Considerations

Vasculitis is defined as inflammation and subsequent necro-

sis of the vessel wall. Various clinical syndromes share vas-

culitis as a feature and may be classified according to the size

and type of involved vessels (eg, postcapillary venule, arteri-

ole, vein, or artery), the type of inflammatory infiltrate (eg,

necrotizing or granulomatous), and the organs affected

(Table 28–5). Some forms of vasculitis are confined to the

skin, whereas others involve internal organs and may cause

severe and potentially fatal disease. When the small vessels of

the skin are involved, the most common finding is palpable

purpura. Involvement of larger vessels produces subcuta-

neous nodules, stellate-shaped purpura, or necrosis.

Pathophysiology

Most of the vasculitic diseases are immunologically mediated

and probably are due to immune complex deposition. The evi-

dence for immune complex–mediated damage is most com-

pelling for small-vessel, or “leukocytoclastic,” vasculitis. The

pathologic process involves the following sequence of events:

deposition of circulating soluble antigen-antibody complexes

in postcapillary venule walls, activation of the complement

cascade, chemotaxis of neutrophils to the sites of immune

complex deposition, and release of lysosomal enzymes and

other products from neutrophils, resulting in necrosis of the

vessel wall. Hemorrhage, thrombosis, and surrounding tissue

necrosis follow. The inflammatory cell infiltrate and edema in

and around the vessels cause the lesions to become palpable. In

some situations, vasculitis may result from direct invasion of

vessels by infectious agents. Cell-mediated immune damage

may be involved in granulomatous vasculitis.

Clinical Features

A. Symptoms and Signs—As noted earlier, the classic cuta-

neous finding in leukocytoclastic vasculitis is palpable pur-

pura (although the palpability may be subtle). However,

hemorrhagic bullae, purpuric plaques, vesicles, pustules on a

purpuric base, and urticaria-like papules may be present.

Affected patients also may have ulcerative, infarcted, or retic-

ulated lesions. The lesions arise in crops, predominantly on

the lower extremities and in dependent areas. Edema of the

lower legs is common. About 40–50% of patients with leuko-

cytoclastic vasculitis have systemic symptoms. Fever, myal-

gias, and arthralgias may accompany the cutaneous

manifestations. Kidney involvement may be transient, with

hematuria or proteinuria, or may lead to glomerulonephritis

or renal failure. Abdominal pain, GI bleeding, and pul-

monary disease (eg, pneumonitis, pleuritis, or hemoptysis)

occur less often. Peripheral neuropathies occur infrequently

and portend a poor prognosis.

B. Laboratory Findings—The definitive diagnosis of cuta-

neous vasculitis depends on compatible cutaneous lesions

plus histopathologic confirmation of blood vessel damage.

Necrotizing vasculitis is characterized by a prominent neu-

trophilic infiltrate in and around the vessel wall associated

with nuclear fragments (“nuclear dust”), extravasated red

blood cells, and deposition of fibrin. Furthermore, granulo-

matous vasculitis shows fibrinoid necrosis of the blood vessels

associated with intravascular and extravascular granulomas.

Evaluation of lesions by direct immunofluorescence for

the presence of immunoglobulins and complement may help

to confirm the diagnosis. However, negative results are com-

mon, and this test is often of little clinical value.

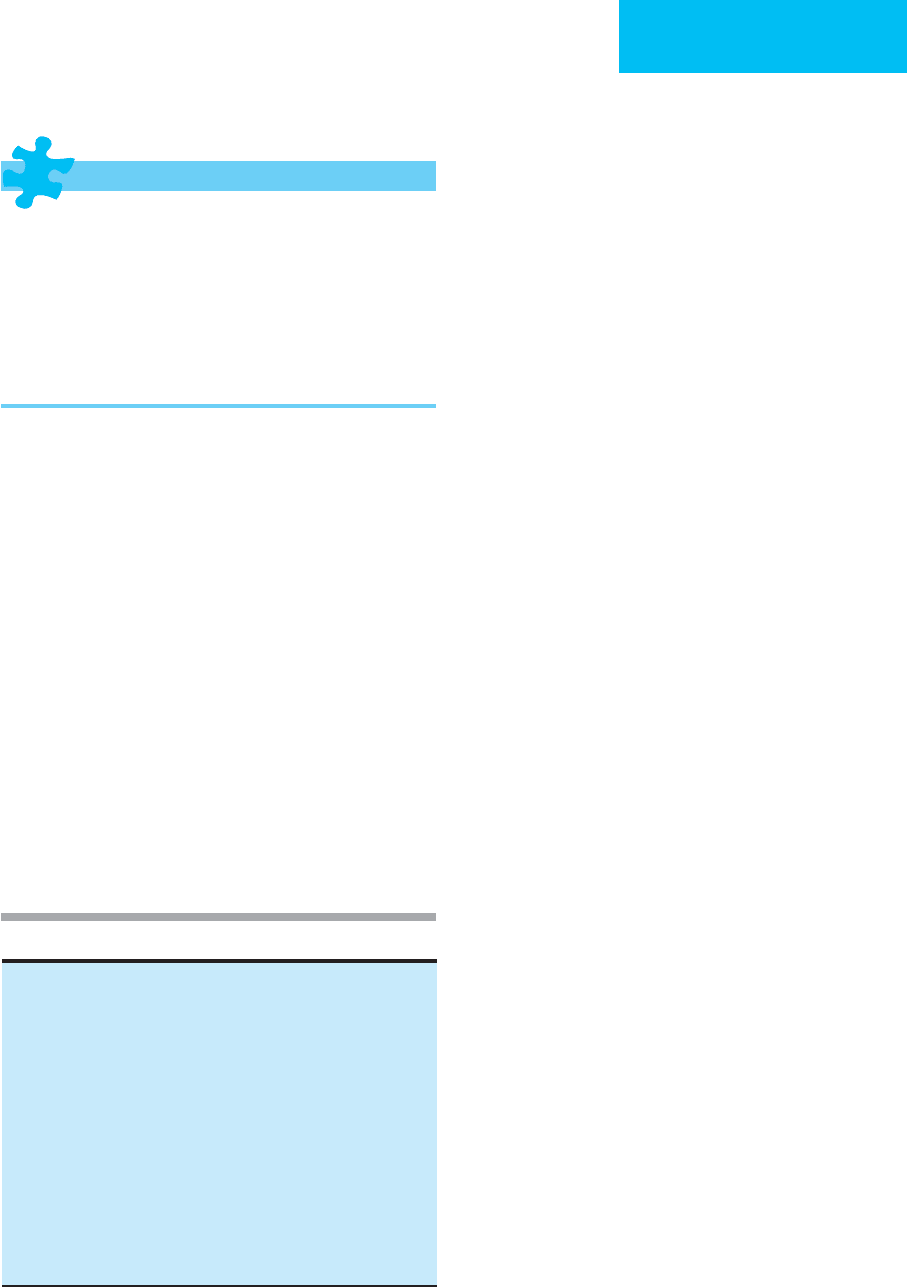

Leukocytoclastic (hypersensitivity) vasculitis

Systemic-cutaneous vasculitis

Variants of leukocytoclastic vasculitis

Urticarial (hypocomplementemic) vasculitis

Serum sickness

Henoch-Schönlein purpura

Rheumatic vasculitis

Systemic lupus erythematosus

Rheumatoid vasculitis

Sjögren’s syndrome

Scleroderma and dermatomyositis

Polyarteritis nodosa

Cutaneous type

Systemic type

Granulomatous vasculitis

Churg-Strauss syndrome (allergic granulomatosis)

Wegener’s granulomatosis

Giant cell arteritis

Temporal arteritis

Takayasu’s arteritis

Miscellaneous

Degos’ disease (malignant atrophic papulosis)

Kawasaki’s disease

Lucio phenomenon

Table 28–5. Classification of vasculitis.

DERMATOLOGIC PROBLEMS IN THE INTENSIVE CARE UNIT

621

Once the diagnosis of cutaneous vasculitis is established, a

comprehensive evaluation is necessary to determine the pres-

ence and extent of internal involvement and to identify poten-

tial underlying causes (Table 28–6). Some recommended

screening studies include the following: complete blood count

and erythrocyte sedimentation rate; chemistry profile; serum

protein electrophoresis and cryoglobulin titer; hepatitis B and

C screens; antinuclear antibody titer, anti-Ro and anti-La titers,

C3, C4, total hemolytic complement, and VDRL; urinalysis and

stool occult blood; throat culture and antistreptolysin O titer;

and chest x-ray. Depending on the clinical situation, other tests

may include antineutrophilic cytoplasmic antibody titers, anti-

cardiolipin antibodies, direct immunofluorescence, biopsy of

affected organs, radiographic studies (including angiograms)

of affected organs, malignancy screening tests, echocardiogra-

phy, visceral angiography, and nerve conduction studies.

Differential Diagnosis

Palpable purpura occurs in both vasculitis and septicemia.

Certain clinical patterns favor the diagnosis of sepsis and

sometimes can provide clues to the causative organism. The

skin lesions associated with staphylococcal sepsis are acrally

located, asymmetric, and fewer in number than those associ-

ated with vasculitis. The characteristic lesions of gonococcal

bacteremia are discrete, tender pustules on a hemorrhagic

base, often accompanied by polyarthralgias, tenosynovitis, or

septic arthritis. The well-known skin findings in infective

endocarditis are painful nodules on the volar surfaces of the

fingers and toes (Osler’s nodes), nontender hemorrhagic mac-

ules on the palms and soles (Janeway’s lesions), and subungual

splinter hemorrhages. Petechiae, ecchymoses, hemorrhagic

vesicles and pustules, and ulcerated nodules all may be seen

with sepsis. The diagnosis is confirmed by a positive blood cul-

ture or a positive culture or Gram stain from the skin lesions.

Palpable purpura also can occur in nonseptic embolic disor-

ders such as atheromatous emboli or left atrial myxoma.

Treatment

The therapy of vasculitis is based on the extent and severity of

the disease. Any associated disease, infection, chemical, or drug

should be treated or removed. For vasculitis limited to the skin,

conservative therapy is appropriate because most cases are acute

and self-limited. Bed rest, antihistamines, and nonsteroidal anti-

inflammatory drugs may suppress or control cutaneous lesions

effectively. For necrotic or highly symptomatic eruptions,

colchicine, dapsone, or prednisone may be useful.

For systemic vasculitis, therapy with immunosuppressive

and/or cytotoxic agents such as corticosteroids, azathioprine,

cyclosporine, methotrexate, and mycophenolate mofetil is

usually necessary. Plasmapheresis may be tried in patients

refractory to other therapeutic modalities. Monoclonal anti-

body therapy with infliximab may be of value.

Cutaneous ulcers or bullae are treated with debridement,

tap water soaks, topical antibiotics, and vapor-permeable

membranes.

Carlson JA, Cavaliere LF, Grant-Kels JM: Cutaneous vasculitis:

Diagnosis and management. Clin Dermatol 2006;24:414–29.

[PMID: 16966021]

Gedalia A: Henoch-Schonlein purpura. Curr Rheumatol Rep

2004;6:195–202. [PMID: 15134598]

Gonzalez-Gay MA, Garcia-Porrua C, Pujol RM: Clinical approach

to cutaneous vasculitis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2005;17:56–61.

[PMID: 15604905]

Hayat S, Berney SM: Cutaneous vasculitis. Curr Rheumatol Rep

2005;7:276–80. [PMID: 16045830]

Langford CA: Vasculitis in the geriatric population. Rheum Dis

Clin North Am 2007;33:177–95. [PMID: 17367699]

Mang R, Ruzicka T, Stege H: Therapy for severe necrotizing vas-

culitis with infliximab. J Am Acad Dermatol 2004;51:331–2.

[PMID: 15280860]

Marder W, McCune WJ: Advances in immunosuppressive drug

therapy for use in autoimmune disease and systemic vasculitis.

Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2004;25:581–94. [PMID:

16088501]

Russell JP, Gibson LE: Primary cutaneous small vessel vasculitis:

Approach to diagnosis and treatment. Int J Dermatol

2006;45:3–13. [PMID: 16426368]

Suresh E: Diagnostic approach to patients with suspected vasculi-

tis. Postgrad Med J 2006;82:483–8. [PMID: 16891436]

Drugs: See Table 28–2.

Chemical

Insecticides

Petroleum products

Weed killers

Foreign proteins

Heterologous serum

Snake antivenin

Hyposensitization antigens

Infections

Group A beta-hemolytic streptococci

Hepatitis B

Mycobacterial diseases

Influenza

Abnormal immunoglobulins

Multiple myeloma

Cryoglobulinemia

Macroglobulinemia

Rheumatic diseases

Rheumatoid arthritis

Systemic lupus erythematosus

Dermatomyositis

Sjögren’s syndrome

Miscellaneous diseases

Ulcerative colitis

Lymphomas and leukemias

Malignant tumors

Idiopathic

Table 28–6. Causes of vasculitis.

CHAPTER 28

622

Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation

& Purpura Fulminans

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Extensive skin necrosis, fever, and hypotension associ-

ated with evidence of disseminated intravascular coag-

ulation.

Sudden appearance of large, irregular areas of purpura,

especially over the extremities.

Skin lesions are tender, enlarge rapidly, and may evolve

into hemorrhagic bullae with subsequent necrosis and

black eschar formation; necrosis of an entire extremity

may develop.

May be associated with pulmonary, hepatic, or renal

failure; GI bleeding; and hemorrhagic adrenal infarction.

General Considerations

Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) is a dynamic

process associated with a variety of underlying diseases and

is the result of uncontrolled activation of coagulation and

fibrinolysis. Purpura fulminans is an acute, severe, often rap-

idly fatal syndrome characterized by extensive necrosis of the

skin associated with fever and hypotension. Purpura fulmi-

nans represents the extreme end of the spectrum of DIC.

Pathophysiology

The central pathogenic events in DIC are excessive generation

of thrombin and formation of intravascular fibrin clots, sec-

ondary activation of the fibrinolytic system, and consump-

tion of platelets and coagulation factors. Abnormalities of the

endogenous anticoagulants protein C and protein S may be

directly related to the pathogenesis of purpura fulminans by

contributing to the thrombotic tendency in patients with

DIC. Neonates with homozygous protein C deficiency present

with massive thrombosis of skin capillaries and veins, result-

ing in cutaneous necrosis, secondary sepsis, and death (pur-

pura fulminans neonatalis). Acquired deficiencies of proteins

C and S have been reported in liver disease and sepsis.

Purpura fulminans occurs most commonly in children and

often follows an infectious process such as scarlet fever or

streptococcal pharyngitis, meningococcemia, varicella, rube-

ola, or Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Purpura fulminans also

has been associated directly with S. aureus strains that pro-

duce high levels of toxic shock syndrome toxin 1 or staphylo-

coccal enterotoxins. Adults also may be affected, and the

syndrome may occur without a preceding illness.

Clinical Features

A. Symptoms and Signs—Cutaneous findings of DIC may

range from insignificant bruising and oozing from venipuncture

sites to massive hemorrhage and necrosis of skin and vital

organs. Purpura fulminans is characterized by the sudden

appearance of large, irregular areas of purpura, especially

over the extremities. The lesions are tender, enlarge rapidly,

and may evolve into hemorrhagic bullae with subsequent

necrosis and black eschar formation. The trunk, ears, and

nose may be involved. Necrosis of an entire extremity may

develop. Fever, chills, and hypotension almost always accom-

pany the disorder. Complications may include pulmonary,

hepatic, and renal failure, as well as GI bleeding and hemor-

rhagic adrenal infarction (Waterhouse-Friderichsen syn-

drome). Mortality rates range from 20–40%. The differential

diagnosis of purpura fulminans encompasses the entire spec-

trum of purpuric conditions.

B. Laboratory Findings—Because of the dynamic balance

between intravascular clot deposition and dissolution, serial

laboratory studies may be required to diagnose and monitor

DIC. The blood count usually shows thrombocytopenia, and

anemia may result from bleeding or microangiopathic

hemolysis. Consumption of coagulation factors and fibrino-

gen causes prolongation of the prothrombin time and partial

thromboplastin time. There is hypofibrinogenemia, and

increased fibrin degradation products (fibrin split products)

are present. More specific tests, such as measurement of the

D-dimer fragment, a breakdown product of cross-linked fib-

rin, may be helpful.

Treatment

Immediate attention must be directed toward stabilizing the

patient and treating the underlying cause. Heparin may pre-

vent further clot formation but should be avoided in patients

with suspected or documented intracranial bleeding. Plasma

or platelet replacement therapy may be indicated in patients

with active bleeding, but efficacy has not been proved in ran-

domized, controlled trials. Recombinant human activated

protein C should be considered in sepsis-related DIC.

Surgical debridement of necrotic eschars, grafting, and even

amputation are sometimes necessary.

Betrosian AP, Berlet T, Agarwal B: Purpura fulminans in sepsis. Am

J Med Sci 2006;332:339–45. [PMID: 17170624]

Fourrier F: Recombinant human activated protein C in the treat-

ment of severe sepsis: An evidence-based review. Crit Care Med

2004;32:S534–41. [PMID: 15542961]

Franchini M, Manzato F: Update on the treatment of disseminated

intravascular coagulation. Hematology 2004;9:81–5. [PMID:

15203862]

Kravitz GR et al: Purpura fulminans due to Staphylococcus aureus.

Clin Infect Dis 2005;40:941–7. [PMID: 15824983]

Levi M, de Jonge E, van der Poll T: Plasma and plasma components

in the management of disseminated intravascular coagulation.

Best Pract Res Clin Haematol 2006;19:127–42. [PMID:

16377546]

Zeerleder S, Hack CE, Wuillemin WA: Disseminated intravascular

coagulation in sepsis. Chest 2005;128:2864–75. [PMID:

16236964]

DERMATOLOGIC PROBLEMS IN THE INTENSIVE CARE UNIT

623

LIFE-THREATENING DERMATOSES

Pemphigus Vulgaris

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Flaccid, easily ruptured blisters on noninflamed skin;

after rupture, nonhealing crusted erosions remain.

Superficial detachment of the skin after pressure or

trauma variably present (Nikolsky’s sign).

Skin biopsy shows characteristic intraepidermal cleft

just above the basal cell layer, with separation of ker-

atinocytes from one another (acantholysis).

Direct immunofluorescence of normal-appearing skin

shows intercellular IgG and complement deposition

throughout the epithelium.

General Considerations

Pemphigus vulgaris is a rare life-threatening autoimmune dis-

ease characterized by intraepithelial vesicles and bullae.

Stratified squamous epithelium of both skin and mucosal sur-

faces is involved. The pathogenic process involves circulating

IgG autoantibodies directed against the intercellular substance

of the epidermis. The mean age at onset is the sixth decade.

Clinical Features

A. Symptoms and Signs—Nonhealing oropharyngeal ero-

sions are common and often precede the skin findings by

weeks or months. The primary cutaneous lesion is a flaccid

blister on noninflamed skin. These blisters rupture easily,

leaving nonhealing erosions that ultimately develop crusts. A

positive Nikolsky sign (tractional pressure adjacent to a

lesion causes skin separation) is characteristic but not

pathognomonic. With treatment, the lesions generally heal

without scarring. The sites of predilection are the scalp, face,

axillae, and oral cavity. The conjunctival, vaginal, and

esophageal mucosa and the vermilion border of the lips also

may be involved. The process may become generalized.

Oropharyngeal involvement causes difficulty in swallowing,

and laryngeal involvement produces hoarseness. Prior to the

availability of corticosteroids, the mortality rate of pemphi-

gus approached 60–90% owing primarily to protein, fluid,

and electrolyte losses or to sepsis. More recently, the mortal-

ity rate has dropped to the range of 5–15%; the most com-

mon causes of death today are infection and complications

of treatment.

B. Laboratory Findings—The diagnosis is based on patho-

logic findings, including skin biopsy showing a characteristic

intraepidermal cleft just above the basal cell layer, with sepa-

ration of keratinocytes from one another (acantholysis). The

acantholytic cells line the vesicle and also lie free within the

cavity. A Tzanck smear from the base of a bulla may show

acantholytic epidermal cells. Direct immunofluorescence of

normal-appearing skin near a lesion shows intercellular IgG

and complement deposition throughout the epithelium.

Indirect immunofluorescence of the patient’s serum demon-

strates circulating intercellular autoantibodies in about

80–90% of patients specific for desmoglein-3 alone when

lesions are limited to the mouth and for both desmoglein-3

and -1 when skin lesions are present in addition to oral lesions.

However, titers of the circulating autoantibodies do not corre-

late with disease severity but often parallel disease activity.

Fluid, electrolyte, and nutritional disturbances may occur

but are less pronounced than in disorders involving loss of

the entire thickness of the epidermis (eg, TEN).

Differential Diagnosis

Histopathologic examination, immunofluorescent microscopy,

and bacterial cultures permit differentiation from EM, SJS,

TEN, bullous drug eruptions, and bullous impetigo, as well

as from other primary blistering diseases such as bullous

pemphigoid and dermatitis herpetiformis.

Treatment

Discontinue drugs known to cause pemphigus (eg, penicil-

lamine and captopril).

A. Specific Treatment—Prednisone, 60–120 mg/day, in com-

bination with azathioprine, 100–150 mg/day, is usually effective.

Prior to initiation of therapy, the patient should be evaluated for

contraindications to systemic steroids. Patients with a history of

tuberculosis or a positive skin test for tuberculosis need con-

comitant isoniazid while receiving immunosuppressive therapy.

When control of the blistering is achieved, prednisone is

reduced gradually as tolerated. Methotrexate, cyclophos-

phamide, mycophenolate mofetil, cyclosporine, intravenous

high-dose immunoglobulins, gold, chlorambucil, and plasma-

pheresis are alternative modalities, as is pulse corticosteroid

therapy. Monoclonal antibodies may be of value in the future.

B. Topical Therapy—Silver sulfadiazine or mupirocin oint-

ment may reduce secondary infection. Whirlpool treatments

are helpful in removing crusts from lesions. Oral mucosal

erosions may benefit from topical steroids, antiseptics, vis-

cous lidocaine, and attention to oral hygiene.

Akerman L, Mimouni D, David M: Intravenous immunoglobulin

for treatment of pemphigus. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol

2005;29:289–94. [PMID: 16391404]

Berookhim B et al: Treatment of recalcitrant pemphigus vulgaris

with the tumor necrosis factor alpha antagonist etanercept.

Cutis 2004;74:245–7. [PMID: 15551718]

Bystryn JC, Rudolph JL: Pemphigus. Lancet 2005;366:61–73.

[PMID: 15993235]

El Tal AK et al: Rituximab: A monoclonal antibody to CD20 used

in the treatment of pemphigus vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol

2006;55:449–59. [PMID: 16908351]

CHAPTER 28

624

Mutasim D: Management of autoimmune bullous diseases:

Pharmacology and therapeutics. J Am Acad Dermatol

2004;51:859–77. [PMID: 15583576]

Ruocco E et al: Life-threatening bullous dermatoses: Pemphigus

vulgaris. Clin Dermatol 2005;23:223–6. [PMID: 15896536]

Stanley JR, Amagai M: Pemphigus, bullous impetigo, and the

staphylococcal scalded-skin syndrome. N Engl J Med 2006;355:

1800–10. [PMID: 17065642]

Generalized Pustular Psoriasis

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Acute onset of widespread sterile pustules arising on ten-

der, warm, erythematous skin that coalesce into lakes of

pus; the tongue and mouth are commonly involved.

Recurrent waves of pustulation and remissions occur;

fever and leukocytosis are often present; bacterial

infections and sepsis may be complications.

Arthritis and pericholangitis are sometimes present;

rarely, there is associated hypotension, high-output

heart failure, and renal failure; a history of psoriasis

may or may not be present.

Characteristic subcorneal pustules are seen on histologic

examination.

General Considerations

In addition to the exfoliative erythrodermic form of psoriasis,

another serious and sometimes fatal type is generalized pus-

tular psoriasis. It is characterized by the acute onset of wide-

spread erythematous areas studded with many sterile pustules

and associated with fever, chills, and leukocytosis. The disease

may develop either de novo or in individuals with a history of

psoriasis. The exact pathogenesis is unclear; however, precip-

itating events include topical and systemic corticosteroid

therapy and its subsequent withdrawal, other medications

(eg, sulfonamide drugs, penicillin, lithium, and pyrazolones),

infections, pregnancy, and hypocalcemia. Pustular psoriasis

tends to occur in patients over 40 years of age.

Clinical Features

A. Symptoms and Signs—The primary lesions are sterile

pustules that arise on tender, warm, erythematous skin and

coalesce into lakes of pus. Lesions typical of psoriasis vulgaris

may coexist. The tongue and mouth are commonly involved,

with geographic tongue and superficial erosions. These

patients appear ill and complain of itching and burning. The

course is punctuated by recurrent waves of pustulation and

remissions. Arthritis and pericholangitis sometimes occur.

Circulatory shunting through the skin may lead to significant

edema and, rarely, hypotension, high-output heart failure,

and renal failure. Superimposed bacterial infections or sepsis

can complicate the clinical picture.

B. Laboratory Findings—Laboratory data are nonspecific

but may be helpful. Leukocytosis, hypoalbuminemia, and

hypocalcemia are seen often during flares of this disorder,

although Gram stains and bacterial cultures of lesions are

negative. HIV serology should be checked because severe

exacerbations of psoriasis can be seen in HIV-infected indi-

viduals. Histologic examination of a lesion shows a charac-

teristic subcorneal pustule.

Differential Diagnosis

The diagnosis of pustular psoriasis is generally clear-cut on

clinical and histologic grounds. Other diagnostic consider-

ations include miliaria rubra, acneiform secondary syphilis,

pustular drug eruptions, and folliculitis. Cellulitis may be

suggested by the marked edema and erythema of the legs.

Treatment

A. Specific Treatment—The drugs of choice in this severe

form of psoriasis are the retinoids acitretin and isotretinoin.

These drugs should not be used in patients with lipid abnor-

malities or active hepatitis, and effective contraception must

be ensured during and for at least 3 years after treatment in

women of childbearing potential. Most patients show signif-

icant improvement in 5–7 days. Precipitating causes, includ-

ing lithium, antimalarials, diltiazem, propranolol, and

irritating topical medications, must be identified and

removed. Withdrawal from systemic corticosteroids is the

most common trigger. Oral acitretin works rapidly; but in

women of childbearing age, isotretinoin may be a better

choice because it has a shorter period of teratogenicity.

Methotrexate and cyclosporine are alternatives in carefully

selected patients; methotrexate is absolutely contraindicated

in HIV-infected patients. Hydroxyurea, mycophenolate

mofetil, and azathioprine have been used in some patients.

Recent case reports suggest that monoclonal antibodies to

tumor necrosis factor-α may be very helpful in patients with

pustular psoriasis. Systemic steroids should be avoided.

B. General Measures—A medium-potency topical steroid

applied twice daily to affected areas, emollient creams, cool

compresses, and baths alleviate discomfort. Attention must

be paid to fluid and electrolyte imbalances. The patient

should be monitored for secondary infection and sepsis.

Aaronson D, Lebwohl M: Review of therapy of psoriasis: The pre-

biologic armamentarium. Dermatol Clin 2004;22:379–88.

[PMID: 15450334]

Benoit S et al: Treatment of recalcitrant pustular psoriasis with

infliximab: Effective reduction of chemokine expression. Br J

Dermatol 2004:150:1009–12. [PMID: 15149518]

de Gannes GC et al: Psoriasis and pustular dermatitis triggered by

TNF-α inhibitors in patients with rheumatologic conditions.

Arch Dermatol 2007;143:223–31. [PMID: 17310002]

Mengesha YM, Bennett ML: Pustular skin disorders: Diagnosis and

treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol 2002;3:389–400. [PMID:

12113648]

DERMATOLOGIC PROBLEMS IN THE INTENSIVE CARE UNIT

625

Exfoliative Erythroderma

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Generalized or nearly generalized diffuse erythema

with desquamation.

Pruritus, malaise, fever, chills, and weight loss may be

present.

There may be a history of primary dermatologic dis-

ease, or the erythroderma may be a sign of malignancy

(T-cell lymphoma); the cause in many cases remains

undetermined.

General Considerations

Exfoliative erythroderma is a clinical syndrome characterized

by generalized or nearly total diffuse erythema of the skin

accompanied by variable degrees of desquamation.

Exfoliative erythroderma is a nonspecific endpoint of skin

reactivity; multiple conditions can lead to it (Table 28–7).

Approximately half of all cases are due to exacerbation of a

primary dermatologic condition. Underlying skin diseases

such as psoriasis and various forms of eczema may become

generalized through neglect, the abrupt discontinuation of

therapy, or intercurrent cutaneous or systemic infection (eg,

HIV-infected individuals are at risk of development of ery-

throdermic psoriasis). Less commonly, exfoliative erythro-

derma is the initial manifestation of a dermatosis. The

remaining cases are nearly equally divided among undeter-

mined causes, drug reactions, and underlying malignancies,

most commonly cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.

Clinical Features

A. History—A careful history with attention to preexisting der-

matoses, family history of skin conditions, medication history,

and clues to occult malignancy may suggest a specific cause.

B. Symptoms and Signs—Most patients complain of pru-

ritus. The entire skin surface is red, scaly, and indurated.

Excoriations, peripheral edema, and moderate symmetric

lymph node enlargement are common; massive or asym-

metric lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly are suggestive

of an underlying lymphoma. The mucous membranes usu-

ally are spared. There may be symptoms of orthostatic

hypotension owing to increased insensible water loss.

Congestive heart failure owing to marked circulatory

shunting through the skin may develop in patients with

preexisting cardiac disease.

Thermoregulatory dysfunction can result in relative

hypothermia and chills, thereby concealing the fever of sep-

sis. Nevertheless, patients with erythroderma owing to

drugs or lymphoma—or patients with secondary infections—

often present with fever. Secondary bacterial infection

manifests as purulent exudate or crusting. Sepsis, pneumo-

nia, and complications of malignancy are the leading causes

of death.

C. Laboratory Findings—Laboratory studies are usually of

limited value in establishing the underlying cause but are

necessary for assessing response to the skin disease.

Leukocytosis and anemia are common, whereas eosinophilia

suggests a drug offender. Atypical circulating lymphocytes

(Sézary cells), if present in sufficiently high numbers, sug-

gest Sézary’s syndrome, the leukemic phase of cutaneous T-

cell lymphoma. Hypoalbuminemia and negative nitrogen

balance result from protein loss by desquamation and an

elevated metabolic rate. Serologic testing for HIV is recom-

mended for patients with erythrodermic psoriasis.

Other tests should include urinalysis and stool occult

blood, chest x-ray, and ECG. Skin biopsy results usually are

nonspecific but may be diagnostic in leukemia, cutaneous T-

cell lymphoma, or Norwegian crusted scabies. Routine

biopsy of superficial lymph nodes is even less helpful because

the pathologic findings are usually reactive (dermatopathic

lymphadenopathy). However, biopsy of unusually promi-

nent or asymmetric lymph nodes may yield a diagnosis of

lymphoreticular malignancy.

Differential Diagnosis

Exfoliative erythroderma should be differentiated from other

conditions associated with diffuse erythema, such as com-

mon morbilliform drug eruptions, various viral and bacter-

ial exanthems, early phases of TEN, toxic shock syndrome,

and graft-versus-host disease.

Treatment

Irrespective of the underlying cause, all exfoliative erythro-

dermas may be treated initially in a similar manner. The

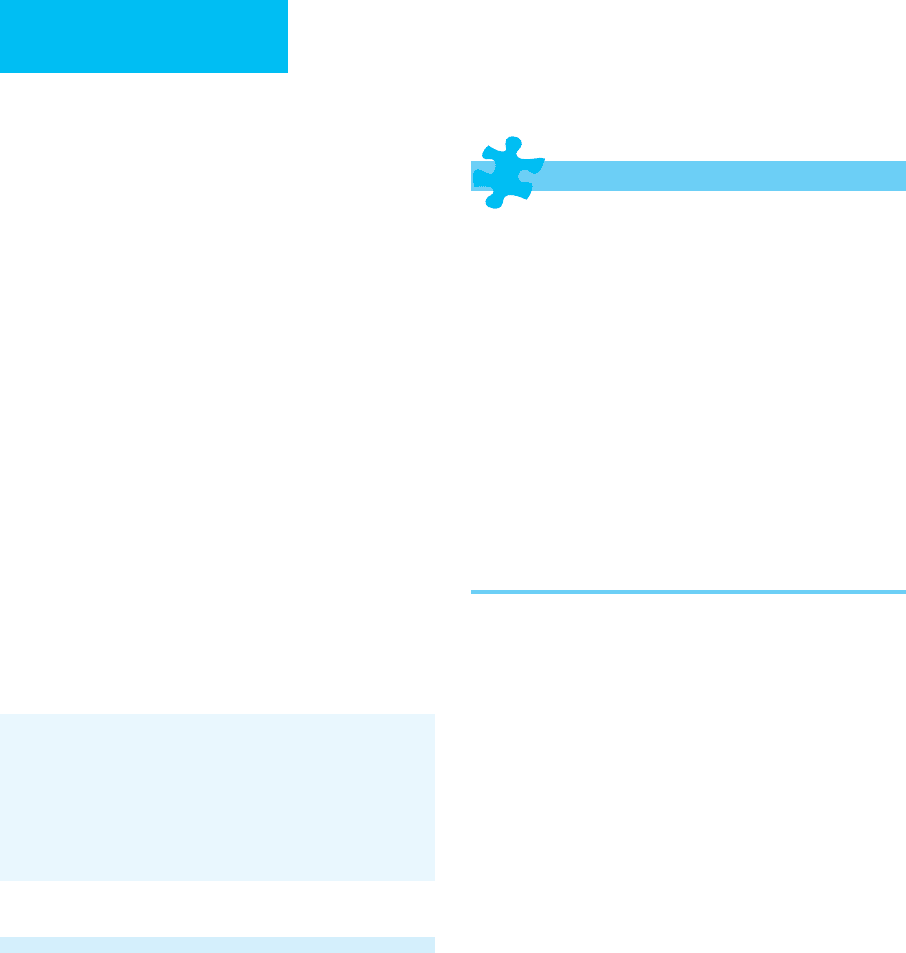

Underlying dermatosis

Eczematous conditions

Contact dermatitis

Atopic dermatitis

Seborrheic dermatitis

Psoriasis

Pityriasis rubra pilaris

Pemphigus foliaceus

Norwegian scabies

Others

Drugs: See Table 28–2.

Malignancies

Cutaneous T cell lymphoma

Hodgkin’s disease

Miscellaneous lymphomas and leukemias

Idiopathic

Table 28–7. Causes of exfoliative erythroderma.

CHAPTER 28

626

goals of therapy are relief of symptoms and reduction of

cutaneous inflammation.

A. Specific Treatment—Once the cause is established, spe-

cific treatment may be initiated. Systemic steroids should be

avoided unless indicated as specific therapy for the underly-

ing disease.

B. General Measures—Patients must be monitored closely

for complications of erythroderma, including anemia, elec-

trolyte imbalances, high-output heart failure, hypothermia,

pneumonia, and sepsis. Administer systemic antibiotics to

patients with cutaneous or systemic infection. Adequate

nutrition is essential. One should stop any potentially

offending medications and keep the patient warm. Daily

whirlpool treatments aid in removing scale and decreasing

bacterial colonization. Baths and wet compresses also may be

used. After each whirlpool treatment, apply a medium-

potency topical steroid such as fluocinolone acetonide

0.025% and bland emollient such as petrolatum to the entire

body; frequent applications of the emollient each day help to

partially restore skin barrier function. Topical medium-

potency steroids such as fluoninolone acetonide 0.025%

ointment may be used 2–3 times daily. Antihistamines are

helpful in controlling pruritus.

Inspect the skin regularly for morphologic changes that

may be diagnostic of an underlying dermatitis as the ery-

throderma subsides.

Akhyani M et al: Erythroderma: A clinical study of 97 cases. BMC

Dermatol 2005;5:5. [PMID: 15882451]

Rothe MJ, Bernstein ML, Grant-Kels JM: Life-threatening erythro-

derma: Diagnosing and treating the “red man.” Clin Dermatol

2005;23:206–17. [PMID: 15802214]

Sigurdsson V et al: Erythroderma: A clinical and follow-up study

of 102 patients, with special emphasis on survival. J Am Acad

Dermatol 1996;35:53–7. [PMID: 8682964]

CUTANEOUS MANIFESTATIONS OF INFECTION

The febrile patient with a rash often presents a clinical

dilemma in that both noninfectious and infectious causes

must be considered. Among the noninfectious causes already

discussed are drug eruptions, vasculitis, and exfoliative ery-

throderma. In addition, systemic lupus erythematosus, juve-

nile rheumatoid arthritis, and Kawasaki’s disease may be

manifested as eruptions associated with fever.

Systemic viral, bacterial, rickettsial, and fungal diseases

may involve the skin, producing a multiplicity of cuta-

neous reactions that, in general, are not pathognomonic

either for infection or for a specific organism. The follow-

ing discussion focuses on life-threatening infections with

sufficiently distinctive skin findings to facilitate early diag-

nosis. Cutaneous manifestations of sepsis were addressed

earlier.

Varicella-Zoster

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Primary infection—varicella

After a prodromal period of 1–3 days, small erythema-

tous macules appear and evolve into clear vesicles; pru-

ritus is intense; new crops appear at 3–5-day intervals.

Vesicles form crusted erosions; oropharyngeal vesicles

rupture quickly to form superficial mucosal ulcers.

In normal adults as well as immunosuppressed indi-

viduals, varicella may be complicated by life-

threatening pneumonia, hepatitis, myocarditis,

encephalitis, and DIC.

Reactivation infection—herpes zoster

Acute, usually painful unilateral eruption in dermatomal

distribution, with clusters of vesicles occurring on a

background of erythema; in persons with compromised

immune systems, the lesions may become severe and

necrotic.

General Considerations

Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) is a herpesvirus that typically

causes a self-limited infection but is capable of producing

life-threatening illness. Primary infection produces varicella;

reactivation of latent virus in sensory ganglia results in her-

pes zoster (shingles). Varicella is spread by direct person-to-

person contact or inhalation of infected droplets. Contact

with the lesions of herpes zoster may produce varicella in a

person not previously infected with VZV.

Clinical Features

A. Symptoms and Signs—After primary exposure to VZV,

the incubation period ranges from 11–21 days but may be

shorter in immunocompromised persons. The prodromal

symptoms in children are minimal and consist of low-grade

fever and malaise. In adults, the symptoms are more severe

and include prolonged fever, malaise, and arthralgias. One to

a few days after onset of illness, small erythematous macules

appear on the trunk, face, and proximal extremities. The pri-

mary lesion evolves rapidly into a clear vesicle that, if left

undisturbed, becomes cloudy. The vesicles eventually rup-

ture to form crusted erosions. New crops appear at irregular

intervals over the next 3–5 days, giving the characteristic

finding of lesions in various stages of development. Pruritus

is often intense. Healing with scarring is not uncommon,

particularly in excoriated or secondarily infected lesions.

Oropharyngeal vesicles rupture quickly to form superficial

mucosal ulcers. In normal adults as well as immunosup-

pressed individuals, varicella may be especially severe and

complicated by life-threatening pneumonia. Hepatitis,