Bongard Frederic , Darryl Sue. Diagnosis and Treatment Critical Care

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

ACUTE ABDOMEN

697

Clinical Features

A. Symptoms—While many patients in the ICU are unable

to give a history because of intubation or altered mental sta-

tus, a detailed review of recent symptomatology should be

obtained whenever possible. Family members and friends

should be interviewed. Patients may have been transferred

from a hospital ward or may have had recent contact with

the hospital or emergency room. However obtained, the his-

tory should describe any preexisting medical conditions,

previous surgery, present medications, prior abdominal

complaints, changes in eating or bowel habits, and recent

weight loss. Exposure to toxic substances (including alco-

hol) and recent trauma should be noted. The obstetric and

gynecologic history should include data about menses and

sexual contacts.

Events leading to hospitalization need to be reviewed,

and if pain is part of the symptomatology, a history of its

presentation and progression is helpful. Despite efforts to

elicit a detailed history, this is often not possible in critically

ill patients.

1. Location of the pain—The location of pain can give

valuable information about its cause. Even more important is

an account of its progression and changes in location

(Table 32–1). Knowing where the pain began occasionally

means more than determining where it is at presentation. A

perforated ulcer may cause lower abdominal pain from intes-

tinal contents collecting in the pelvis owing to gravitational

effects or even owing to a pelvic abscess, whereas a detailed

history may reveal days or weeks of epigastric or right upper

quadrant pain. Pain radiating to some other area of the body

also may give valuable information. For example, epigastric

pain that radiates through to the back is more likely to be due

to pancreatitis than to reflux esophagitis.

2. Nature of the pain—Episodic or crampy pain is usually

due to blockage or obstruction of a hollow viscus during

contraction or attempted peristalsis such as in bowel

obstruction or during an attack of acute cholecystitis.

Questioning and observation often will determine what fac-

tors increase or relieve the pain. Patients with direct peri-

toneal inflammation will resist movement, whereas patients

with renal colic will writhe about with no apparent exacerba-

tion from the movement itself.

3. Progression of the pain—Since virtually all patients

subjected to abdominal operations have postoperative pain,

progression of the pain gives important information about

its source. Incisional pain usually begins to subside after the

first 72 hours, whereas pain owing to other causes such as an

intraabdominal abscess or bowel obstruction often will begin

after 72 hours and become progressively worse.

B. Physical Examination—A comprehensive physical

examination of the ICU patient can be difficult and frustrat-

ing, especially just after an operation. Nevertheless, a com-

plete examination is essential on admission to the unit,

starting with measurement of routine vital signs. Body

temperatures should be obtained from a reliable site—rectal,

bladder, or core measurements from a Swan-Ganz catheter

probe will suffice. Oral and axillary temperatures are often

unreliable. Fever with or without hypotension arouses sus-

picion of abdominal disease, and the presence of both often

will suggest an acute abdomen. Examination to exclude an

extraabdominal source of sepsis should include inspection

of old and existing intravenous sites, chest auscultation

and percussion, inspection of all wounds (traumatic and

surgical), and gross evaluation of urine, especially in

catheterized patients.

1. Observation—Abdominal examination should begin

with careful observation of not only the abdomen but also

the patient’s body position and general demeanor. Is the

patient resting comfortably or in significant distress, with

guarding of the abdominal area? Any distention, ecchymoses,

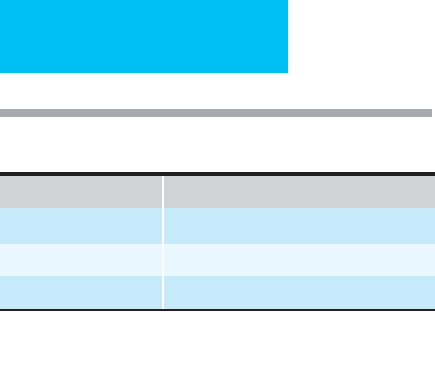

Table 32–1. Locations of common etiologies of acute

abdomen.

Epigastrium Suprapubic and Pelvic

Esophageal disease Cystitis

Peptic ulcer disease Diverticulitis

Pancreatitis (including Proctitis

pseudocyst) Pelvic abscess

Cardiac disease Renal colic

Hiatal hernia (including Left Upper Quadrant

paraesophageal) Pancreatitis (including pseudocyst)

Right Upper Quadrant Splenic disease

Cholecystitis Hiatal hernia (including

Cholangitis paraesophageal)

Pancreatitis (including Renal colic

pseudocyst) Left lower lobe pneumonia

Peptic ulcer disease Colitis (especially ischemic)

Renal colic Subphrenic abscess

Hepatitis Periumbilical

Appendicitis Umbilical hernia

Cecal volvulus Early appendicitis

Hepatic abscess Small bowel obstruction

Subphrenic abscess Mesenteric ischemia

Right lower lobe pneumonia Aortic aneurysm

Right Lower Quadrant Left Lower Quadrant

Appendicitis Diverticulitis

Diverticulitis Sigmoid volvulus

Crohn’s disease Colitis (especially ischemic)

Colonic obstruction Renal colic

Psoas abscess Inguinal hernia

Pelvic inflammatory disease Pelvic inflammatory disease

Ovarian cyst or torsion Ovarian cyst or torsion

Ectopic pregnancy Ectopic pregnancy

Inguinal hernia Epididymitis

Epididymitis Pelvic abscess

Pelvic abscess Psoas abscess

CHAPTER 32

698

and old surgical scars should be noted. Some abdominal dis-

tention is normal in the postoperative abdominal surgical

patient, but any increase in distention postoperatively may

signify problems such as a nonfunctioning nasogastric tube,

prolonged ileus, small bowel obstruction, or development of

ascites. Recent incisions should be inspected, and any ery-

thema, edema, or fluid discharge should alert the examiner

to a potential wound or intraabdominal infection.

2. Auscultation—Auscultation is difficult in a noisy ICU

environment and therefore frequently neglected. Absent

bowel sounds may be normal in recent postoperative patients

but in others may be viewed appropriately with suspicion.

Hyperactive, high-pitched rushes may signify bowel obstruc-

tion. Abdominal bruits indicate the presence of aneurysms,

arteriovenous fistulas, or severe atherosclerotic disease.

3. Percussion—Gentle percussion with close attention to

grimacing or other movement by the patient can give sub-

tle information about localized peritoneal irritation. The

presence of a tympanic area in the right upper quadrant

overlying the liver suggests pneumoperitoneum. Percussion

also can help to detect bowel obstruction (calling for naso-

gastric intubation) or ascites or may disclose a distended

bladder owing to a nonfunctioning or nonexistent Foley

catheter.

4. Palpation—Palpation may reveal hepatomegaly or

splenomegaly, an abdominal wall hernia, a distended gall-

bladder, an intraabdominal tumor or abscess, or an aortic

aneurysm. Rebound tenderness is intended to elicit peri-

toneal irritation. Gentle percussion is a good test for local-

ized peritonitis. Gently bumping the patient or the bed or

having the patient cough will cause enough peritoneal move-

ment to exacerbate pain from peritoneal inflammation.

Careful observation of the patient’s facial expression and

body position will be revealing. Deep palpation of the

abdominal wall and sudden release to elicit rebound tender-

ness is often misleading and in the presence of peritonitis

often will increase guarding and make subsequent examina-

tions more difficult.

When cholecystitis is in the differential diagnosis, right

upper quadrant palpation may reveal tenderness or even a

positive Murphy sign (ie, arrested inspiration during palpa-

tion of the right upper quadrant). Although the retroperi-

toneum and pelvis are less accessible to direct palpation,

indirect evidence of inflammation can be elicited. Pain on

hyperextension of the hip, on stretching the iliopsoas muscle

(psoas sign), and on flexion and internal rotation of the hip,

stretching the obturator muscle (obturator sign), can indi-

cate an adjacent inflammatory process. Gentle palpation or

percussion of the posterior costovertebral angles should

diagnose or exclude pyelonephritis.

5. Rectal and pelvic examination—Genitourinary and

rectal examinations are essential to evaluate for incarcerated

hernias, pelvic or rectal masses, cervical motion tenderness,

prostatic or scrotal disease, and bloody stools. Stool may be

guaiac-tested to confirm a clinical suspicion, but—at least in

the ICU patient population—this test is too insensitive and

nonspecific to be useful in making clinical decisions.

C. Laboratory Findings—A white blood cell count is non-

specific and relatively insensitive—its absolute level is less

useful than its trend. A differential count indicating a left

shift increases the sensitivity of this test. The hematocrit is

helpful or even essential in diagnosing intraabdominal or GI

bleeding.

Urinalysis should be performed with attention to the

presence of white blood cells or white blood cell casts indica-

tive of urinary tract infection. Urine specific gravity can give

information useful in fluid resuscitation efforts, and the

presence of glucose or ketones is of diagnostic and therapeu-

tic importance.

Elevated liver enzymes (eg, AST, ALT, and alkaline phos-

phatase) direct attention to the liver (eg, hepatitis) and bil-

iary system (eg, cholangitis or cholecystitis). Bilirubin

elevation is seen in hepatobiliary disease but also can be asso-

ciated with sepsis, hemolysis, and cholestasis owing to par-

enteral nutrition.

Serum amylase is neither sensitive nor specific, although

markedly elevated values usually indicate pancreatitis.

Elevated serum amylase is also seen with perforated ulcer,

mesenteric ischemia, facial trauma, parotitis, and ruptured

ectopic pregnancy. Lipase or Pankrin values may improve

specificity in the diagnosis of pancreatitis. Arterial blood gas

measurements may demonstrate acidosis or hypoxia. Acidosis

may reflect severe sepsis or ischemia, whereas hypoxia may

reflect acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) owing to

uncontrolled sepsis. Additionally, arterial lactate levels may be

more specific in identifying worsening acidosis, especially in

the setting of preexisting acidosis such as renal failure.

D. Imaging Studies—Although bedside studies are rela-

tively risk free, CT scans, MRI, arteriography, and nuclear

medicine scans usually require patient transport. In this

select group of critically ill patients, transfer to other areas of

the hospital carries significant risks.

1. Bedside films—Radiographs of the chest can evaluate for

pulmonary infections as well as free air when performed

with the patient in a sitting position. Pleural effusions, espe-

cially when asymmetric, may signify an intraabdominal

process. Abdominal radiographs may show a colonic volvu-

lus or obstructed bowel gas pattern, biliary or renal calculi, or

(rarely) pneumobilia. Ultrasound can be useful as a diagnos-

tic and therapeutic tool—intraabdominal abscesses can be

identified with this procedure and percutaneous drainage

facilitated. Cholecystitis (calculous or acalculous) can be

diagnosed and even treated (percutaneous cholecystostomy).

In questionable cases, percutaneous aspiration with analysis

of gallbladder contents (ie, Gram stain and culture) can be

invaluable.

2. Radiology department studies—CT scans have

assumed a primary position in the diagnosis of acute

ACUTE ABDOMEN

699

abdomen. They should not be used indiscriminately, how-

ever, and are of little value in the first week after abdominal

surgery, when normal postoperative findings (ie, blood, air,

and seromas) make identification of an abscess difficult. In

the critically ill patient with multiple-organ-system failure,

transport to the radiology department may carry a greater

risk than the potential benefit. These patients perhaps

should be considered for early laparotomy. CT scanning for

intraabdominal abscesses has an accuracy rate greater than

95%. Studies that have looked specifically at critically ill sur-

gical patients, however, are not so promising, with sensitiv-

ity rates as low as 50% and with only 25% of the scans

actually providing beneficial information that perhaps

altered the outcome of therapy. CT scans should be per-

formed only when the information obtained is expected to

have that result.

GI contrast studies can be useful occasionally in patients

with recent anastomoses or in those with possible missed

injuries (especially esophageal injuries). In general, water-

soluble agents (eg, Gastrografin) should be used.

Angiography is useful in patients with suspected mesenteric

ischemia and should be performed early after initial resusci-

tation. In addition to securing the diagnosis, intraarterial

vasodilators (eg, papaverine) can be used as primary therapy

or to demarcate and salvage marginally viable intestine.

Angiography also plays a diagnostic role in selected patients

with GI bleeding, aiding in localization of the bleeding site,

and it has therapeutic applications in the delivery of intraar-

terial vasopressin or embolization. Blood loss of at least

0.5 mL/min is required before it can be detected by angiog-

raphy.

99m

Tc-tagged red blood cell scans have a reported sen-

sitivity of 0.05–0.1 mL/min and may play a role in screening

patients for the more invasive angiographic approach.

Gallium- or indium-tagged white blood cell scans are

useful occasionally in relatively stable patients. The poor

specificity of the tests, especially in the postoperative patient,

and the 24–48-hour time period for completion limit their

usefulness.

E. Peritoneal Lavage—Extensively used in abdominal

trauma, diagnostic peritoneal lavage also may be quite useful

in selected ICU patients. The same factors that make assess-

ment of critically ill patients difficult (eg, altered mental sta-

tus, intubation, etc.) make lavage an attractive alternative.

Numerous studies have shown its utility in selected patients

with white blood cell counts greater than 500/μL or red

blood cell counts greater than 50,000–100,000/μL. Lavage

has limited if any usefulness in the recent postoperative

patient. In this setting, CT- or ultrasound-guided percuta-

neous aspiration is safer and more reliable.

F. Endoscopy—In the presence of active upper GI bleeding,

esophagogastroduodenoscopy is of proved diagnostic and

therapeutic benefit. Flexible sigmoidoscopy and colonoscopy

also may be of diagnostic value in the patient with possible

ischemic colitis or pseudomembranous colitis. Up to a third

of patients with pseudomembranous colitis have negative

C. difficile toxin assays; visualization and biopsy will increase

the diagnostic accuracy to over 95%. Ischemic colitis can

occur as a result of embolic disease, shock (low-flow state),

or—not uncommonly in the ICU setting—after aortic sur-

gery. Endoscopy can confirm the diagnosis and can allow

observation of the progression of disease in selected patients.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography has a

proven therapeutic role in septic patients with cholangitis,

allowing stone extraction or stenting.

Evaluation of the Postoperative Abdomen

Postoperatively, a number of potential intraabdominal com-

plications can occur in the ICU patient. These include such

diverse problems as intraperitoneal bleeding, anastomotic

dehiscence, early small bowel obstruction, and fascial dehis-

cence. Early recognition and aggressive corrective action are

required.

To identify a failure to recover on schedule after laparo-

tomy, one must understand the normal course following

major abdominal surgery. Third-space fluid sequestration

occurs in approximate proportion to the magnitude of the

surgery. Mild to moderate abdominal distention and olig-

uria—frequently seen in the first 24–72 hours after sur-

gery—can make identification of postoperative hemorrhage

difficult. Not infrequently, a declining hematocrit is attrib-

uted to dilutional effects or to equilibration. The accompany-

ing tachycardia may be falsely attributed to pain. Alert

watchfulness for possible postoperative bleeding can avert a

disastrous outcome.

Fever is the most commonly observed postoperative

physiologic abnormality. The presence of fever suggests

infection, but the approach to evaluation must be methodi-

cal. A single febrile episode in most patients should call for

nothing more than a review of the history and a physical

examination. Intermittent spikes of recurrent fever may war-

rant a more thorough investigation—again directed by a

thorough physical examination. The goal should be to iden-

tify a complication early while intervention still may improve

the outcome.

Other than missed injuries to hollow viscera (traumatic

or iatrogenic), intraabdominal sepsis—including abscess and

anastomotic leaks or dehiscences—typically is manifested

between 5 and 10 days after surgery. Early recognition and

treatment are critical. Subtle signs may aid in early diagnosis.

Third spacing should resolve within 48–96 hours, and obser-

vation of a vigorous postoperative diuresis during this period

is a reliable sign of improvement. Leukocytosis following

major surgery is frequently regarded as a normal finding

(largely owing to demargination), whereas failure of the

white blood cell count to return to normal or an increase

from a declining value should suggest the possibility of

intraabdominal sepsis. Other findings include glucose intol-

erance, continued tachycardia, worsening acidosis, pro-

longed ileus, or persistent diarrhea on return of bowel

function (owing to adjacent pelvic abscess).

CHAPTER 32

700

Treatment

Following the initial evaluation of an ICU patient for consid-

eration of an acute abdomen, the primary decision is

whether urgent surgery is required. Resuscitation with intra-

venous fluids is usually necessary to correct third-space

losses or bleeding. A bladder catheter should be inserted to

monitor urine output and, unless contraindicated, a naso-

gastric tube to decompress the stomach. Both H

2

blockers

and antacids are effective, with greatest efficacy achieved by

maintaining the gastric pH higher than 5.0. An arterial and a

pulmonary artery flotation catheter may be necessary in some

patients to monitor hemodynamic function and intravascular

volume. Antibiotics should be given as indicated. Caution

should be exercised in giving antibiotics to patients with

undiagnosed but suspected sepsis because of concerns about

obfuscating the clinical picture and frustrating further evalu-

ation. Antibiotic therapy is largely adjunctive, although small

abscesses or phlegmonous processes owing to contained

enteric leaks often will resolve with their use.

SPECIFIC PATHOLOGIC ENTITIES

Bowel Obstruction

The diagnosis of early postoperative small bowel obstruc-

tion frequently is delayed primarily because of the differen-

tial consideration of persistent adynamic ileus. The

characteristic symptoms of obstruction include abdominal

distention, obstipation, and vomiting. These symptoms also

characterize adynamic ileus, and the first step in differentia-

tion is consideration of the diagnosis. Further confusing the

clinical picture is the side effect of opioid analgesics on

decreasing GI motility.

The clinical history and physical examination are often

nondiagnostic, although the patient who has brief return of

GI function followed by its cessation probably has an adhe-

sive obstruction. Plain radiographs likewise are frequently

nondiagnostic in this setting.

A nasogastric tube should be inserted. Hypovolemia

should be corrected and electrolytes checked, with special

attention to hypokalemia and hypocalcemia. If there is a pos-

sibility of intraabdominal abscess or sepsis, CT scan or ultra-

sonography is indicated. If the diagnosis is still in doubt, a

water-soluble contrast study (eg, Gastrografin) can be diag-

nostic as well as therapeutic because of the cathartic effect of

the hyperosmolar solution. Drainage of an abscess may

relieve the localized ileus or obstruction. Patients who are

receiving adrenal corticosteroids may develop adynamic ileus

if the drug is withdrawn too quickly. High doses (300 mg

hydrocortisone daily or equivalent) intravenously will give

prompt resolution.

Complete obstruction warrants reoperation as soon as

resuscitation is complete. Partial obstruction often will resolve

with conservative management.

Enteric Fistula

Risk factors for enteric fistula include previous radiation,

inflammatory bowel disease, and chronic corticosteroid

administration. After initial resuscitation, the first maneuver

is to determine the need for early operation. A controlled fis-

tula is present when enteric contents are captured by a drain

or when rapid egress from a wound results in little or no

peritoneal contamination or irritation—such cases can be

expected to resolve with nonoperative therapy. Percutaneous

drainage of an associated abscess found by ultrasound or CT

scan may allow closure of the fistula and improve the

patient’s physiologic status prior to definitive management.

Complicating conditions include radiation damage, malig-

nancy, inflammatory bowel disease, the presence of a foreign

body, and distal intestinal obstruction. Water-soluble con-

trast studies are occasionally helpful to visualize the site of

fistula, evaluate the adequacy of drainage, and rule out distal

obstruction. Once a decision to attempt conservative man-

agement is made, useful therapeutic maneuvers may include

restriction of oral intake, parenteral nutrition, octreotide

acetate (50–200 μg subcutaneously twice to three times

daily), and nasogastric suction. Elemental diets may be sub-

stituted for parenteral nutrition in selected patients—especially

those with distal fistulas or with fistulas not in continuity

(eg, duodenal stump and pancreatic).

Conversely, an anastomotic leak or dehiscence that results

in free peritoneal spillage requires emergent operation for

patient survival. The clinical setting and physical examina-

tion usually will allow an accurate assessment. Oliguria and

hypovolemia often portend extensive peritoneal contamina-

tion and third spacing, whereas diffuse peritoneal irritation

manifested by a rigid abdomen on examination offers no real

dilemma. The patient with localized peritoneal signs, mild to

moderate leukocytosis, and perhaps minimal additional fluid

requirements presents a more difficult decision.

Intraabdominal Abscess

Intraabdominal abscess is usually the result of contamination at

the time of surgery or leakage of enteric contents. The process

has been contained by the patient’s immune system and

defense mechanisms, including the omentum. Antibiotics—

especially with smaller collections—may resolve the process.

Larger abscesses—especially those with continued enteric

communication—may require percutaneous or open drainage

or even intestinal resection to control the process. The exact

role and limitations of percutaneous drainage seem to depend

more on the availability of an experienced interventional radi-

ologist than on any absolute criteria, although multiloculated

and interloop abscesses may be less amenable to this tech-

nique. Success rates range from 25–100%. Infected pancreatic

necrosis and other phlegmonous processes are not amenable

to the percutaneous approach. Of particular importance is

appropriate attention to ensure continued success, including

catheter irrigations, frequent rescanning, and contrast studies.

ACUTE ABDOMEN

701

Cholecystitis

Patients in the ICU may develop calculous or acalculous

cholecystitis as well as cholangitis or biliary pancreatitis. The

diagnosis may already be known or suspected, as in the

patient admitted for observation of acute pancreatitis, or

may be a confounding factor, as in the recent cardiac surgical

patient developing acalculous cholecystitis.

The typical findings of right upper quadrant pain, fever,

and Murphy’s sign may not be present even in an awake,

responsive patient. Elevated liver enzymes or unexplained

fever often prompt consideration of biliary disease. Well-

recognized risk factors for cholecystitis (ie, NPO, parenteral

nutrition, recent surgery, and shock) should arouse suspi-

cion. Perhaps the main difficulty is the lack of a reliable diag-

nostic examination in a critically ill patient, especially one

with acalculous disease. The findings of sludge in the gall-

bladder by ultrasound and nonvisualization on

99m

Tc-HIDA

scan are nonspecific and even expected in patients being

maintained on long-term parenteral nutrition. The tech-

nique of percutaneous cholecystostomy (transhepatic) or

aspiration of gallbladder contents with analysis (eg, Gram

stain and culture) can be useful and deserves consideration

in the most unstable patients. The diagnosis remains largely

a clinical one, and exploration is often required for confirma-

tion and treatment. Surgical exploration frequently is based

on clinical suspicion and nonexclusionary test results.

Colonic Pseudo-Obstruction (Ogilvie’s

Syndrome)

Typical findings include abdominal distention, abdominal

pain, and obstruction. Plain abdominal radiographs are usu-

ally diagnostic, although contrast studies or endoscopy may

be necessary to exclude volvulus and distal colonic obstruc-

tion. Predisposing factors include bed rest, spinal fractures

and cord injuries, and prolonged opioid use. Treatment is

required when the cecal diameter exceeds 10 cm on a plain

film of the abdomen. Therapy should include correction of

electrolyte disturbances (especially hypokalemia), cessation

of narcotics, and nasogastric decompression to prevent fur-

ther gaseous distention. Neostigmine has emerged as the

treatment of choice. If the cecal diameter exceeds 12 cm, and

if there is no improvement with the preceding measures,

colonoscopic decompression is usually effective, with

15–20% of patients requiring repeated procedures. Operative

treatment (eg, tube cecostomy or right colectomy) is reserved

for patients with signs of present or impending perforation

or a situation in which a skilled endoscopist is not available.

Abdominal Compartment Syndrome

The concept of elevated intraabdominal pressure having

detrimental clinical sequelae was enunciated over two

decades ago. Initially, renal “toxicity” was focused on, and

oliguria remains one of the earlier clinical signs. Other

sequelae include pulmonary compromise and mesenteric

ischemia. The important factors to keep in mind are to have

a high index of suspicion (especially in patients with signifi-

cant abdominopelvic trauma), to use bladder pressure meas-

urements as a reflection of intraabdominal pressure, and to

consider or perform decompressive laparotomy early if indi-

cated. Control of the open abdomen may be accomplished by

superficially securing an opened 3-L intravenous fluid bag.

Also, the application of an external vacuum-assisted closure

(VAC) device can be applied in this setting.

CURRENT CONTROVERSIES & UNRESOLVED

ISSUES

Bacterial Translocation and Enteral Feedings

The clinical picture of a critically ill patient succumbing to

sepsis and multiple-organ-system failure without any appar-

ent septic focus is a not infrequent clinical problem. A large

volume of data—largely experimental or anecdotal—points

to bacterial translocation across a dysfunctional GI barrier as

the cause. Attempts at correction or prevention have

included selective gut decontamination, maintenance of

intravascular volume, and enteral feedings. Adequate enteral

feedings initiated early appear to maintain adequate GI bar-

rier function. Crucial to this effect seems to be the amino

acid glutamine, a specific nutrient that supports intestinal

mucosal cell growth and replication. Glutamine-containing

enteral nutrition may prevent or at least lessen the severity of

multisystem organ failure induced by bacterial translocation

and bypass the difficulties inherent in enteral feedings in this

group of patients. Additionally, the concept of “immune

enhancing” diets rich in arginine, nucleotides, and fish oil is

being investigated.

Activated Protein C and Corticosteroids in Sepsis

Despite recent advances in critical care, patients continue to

succumb to septic states. This may occur as a result of

delayed recognition or presentation, diminished immune

responses, or overwhelming insults.

Sepsis is associated with widespread inflammation and

intravascular coagulation. Activated protein C is an anticoag-

ulant currently being evaluated in the setting of sepsis, dif-

fuse systemic inflammation, and multiple-organ-system

dysfunction. A recent study has shown a statistically signifi-

cant decrease in 28-day mortality associated with use of acti-

vated protein C. Downsides to use of this drug include its

cost and the associated risk of coagulopathy.

The use of corticosteroids in septic patients is widely con-

troversial. One recent study revealed that small-dose hydro-

cortisone and fludrocortisone in very select patients

conferred a slight decrease in mortality. However, the routine

use of corticosteroids in all patients with sepsis is not justi-

fied. Further research is needed on this topic.

CHAPTER 32

702

Monoclonal Antibodies

Numerous monoclonal antibodies have been tested and

show promise. These agents are targeted against mediators of

sepsis and in no way obviate standard identification and

treatment of the septic source. They include antibodies

against gram-negative endotoxin as well as tumor necrosis

factor and interleukin-1. Of these, monoclonal antibodies

against tumor necrosis factor are the only ones with proven

efficacy in human trials, albeit with a modest benefit

(3.5–4% increase in survival). Appropriate selection of

patients and timing of therapy are among the ongoing clini-

cal issues. Additionally, their widespread use may be limited

by the expected prohibitive costs.

Laparoscopy

The laparoscope has become a common tool of the general

surgeon in the last 20 years, and it is only natural that its role

in critical care patients has been explored. The laparoscope is

likely to be mainly a diagnostic instrument for the near

future because of the untoward cardiovascular and respira-

tory side effects of prolonged abdominal insufflation, espe-

cially in this group of high-risk patients. If anecdotal results

are supported by further prospective investigations,

laparoscopy may supplant peritoneal lavage for the bedside

diagnosis of peritonitis or visceral perforation.

REFERENCES

Annane D et al: Effect of treatment with low doses of hydrocortisone

and fludrocortisone on mortality in patients with septic shock.

JAMA 2002;288:862–71. [PMID: 12186604]

Bernard GR et al: The Recombinant Human Activated Protein C

Worldwide Evaluation in Severe Sepsis (PROWESS) Study Group:

Efficacy and safety of recombinant human activated protein C for

severe sepsis. N Engl J Med 2001;344:699–709. [PMID: 11236773]

Bower RH et al: Early enteral administration of a formula (Impact)

supplemented with arginine, nucleotides, and fish oil in intensive

care unit patients: Results of a multicenter, prospective, random-

ized, clinical trial. Crit Care Med 1995;23:436–49. [PMID:

7874893]

Chambers A et al: Therapeutic impact of abdominopelvic computed

tomography in patients with acute abdominal symptoms. Acta

Radiol 2004;45:248–53. [PMID: 15239417]

Dhillon S et al: The therapeutic impact of abdominal ultrasound in

patients with acute abdominal symptoms. Clin Radiol

2002;57:268–71. [PMID: 12014871]

Fusco MA et al: Estimation of intra-abdominal pressure by bladder

pressure measurement: validity and methodology. J Trauma

2001;50:297–302. [PMID: 11242295]

Gagne DJ et al: Bedside diagnostic minilaparoscopy in the intensive

care patient. Surgery 2002;131:491–6. [PMID: 12019400]

Gajic O et al: Acute abdomen in the medical intensive care unit. Crit

Care Med 2002;30:1187–90. [PMID: 12072666]

Galban C et al: An immune-enhancing enteral diet reduces mortal-

ity rate and episodes of bacteremia in septic intensive care unit

patients. Crit Care Med 2000;28:643–8. [PMID: 10752808]

Gracias VH et al: Abdominal compartment syndrome in the open

abdomen. Arch Surg 2002;137:1298–1300. [PMID: 12413323]

Grassi R et al: Serial plain abdominal film findings in the assessment

of acute abdomen: spastic ileus, hypotonic ileus, mechanical ileus

and paralytic ileus. Radiol Med (Torino) 2004;108:56–70.

Kapadia F: Role of ICU in the management of the acute abdomen.

Indian J Surg 2004;66:203–8.

Keim V et al: Evaluation of Pankrin, a new serum test for diagnosis

of acute pancreatitis. Clin Chim Acta 2003;332:45–50. [PMID:

12763279]

Naidu VV et al: Diagnostic peritoneal lavage (DPL): Is it useful deci-

sion making process for management of the equivocal acute

abdomen? Trop Gastroenterol 2003;24:140–3. [PMID: 14978990]

Newton E et al: Surgical complications of selected gastrointestinal

emergencies: pitfalls in management of the acute abdomen.

Emerg Med Clin North Am 2003;21:873–907. [PMID: 14708812]

Pecoraro et al: The routine use of diagnostic laparoscopy in the inten-

sive care unit. Surg Endosc 2001;15:638–41. [PMID: 11591958]

Tjiu CS et al: Severe acute respiratory syndrome mimicking acute

abdomen. Aust NZ J Surg 2004;74:179–80.

703

33

Sofiya Reicher, MD

Viktor Eysselein, MD

Overt gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding is a quintessential gas-

troenterologic emergency. Appropriate and timely patient

resuscitation and treatment are crucial. GI bleeding carries

considerable morbidity, and 7–10% mortality rates have

been reported. Mortality is up to 30% in patients with in-

hospital onset of GI bleeding. GI bleeding is common, with

incidence of 20–100 per 100,000 adults.

Management of GI bleeding presents unique challenges

owing to the wide spectrum of etiologies, clinical presenta-

tions, and diagnostic and treatment modalities. Furthermore,

treatment approaches to GI bleeding have changed signifi-

cantly over the past decade.

This chapter discusses major causes of severe GI bleeding,

focusing on management aspects pertinent to critical care

medicine. We consider bleeding as severe when hemoglobin

falls acutely by more than 2 g/dL, requiring patient hospital-

ization and consideration of blood transfusion. Occult GI

bleeding is not discussed in this chapter.

Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Hematemesis and melena: hematochezia is almost

always lower GI bleeding but may be seen with severe

upper GI bleeding.

Ulcers/erosions and varices are responsible for the

majority of upper GI bleeding.

Lifelong risk of variceal bleeding is about 50% in cir-

rhotic patients.

Hemodynamic status and comorbid illnesses are key in

the initial assessment of a bleeding patient. Age, syn-

cope or orthostatic change in blood pressure, fresh blood

in the emesis or nasogastric aspirate, or presence of car-

diopulmonary or liver disease portend poor prognosis

and need for urgent endoscopy.

General Considerations

Upper gastrointestinal (UGI) bleeding is defined by the loca-

tion of bleeding lesion proximal to the ligament of Treitz.

UGI bleeding is five to six times more common than lower

GI bleeding. It is found twice as frequently in men than in

women. Despite recent advances in management and treat-

ment, UGI bleeding mortality and medical costs remain

high. In the United States, UGI bleeding accounts for more

than 300,000 hospital admissions annually with an estimated

cost of $750 million.

Clinical Presentation

Hematemesis (vomiting of blood) is the hallmark of UGI

bleeding. Bright red blood in the emesis or in nasogastric

(NG) aspirate is indicative of recent active bleeding, whereas

“coffee grounds” indicate older blood that has had time to be

reduced by acid in the stomach. Melena, another frequent

complaint, is black tarry stools with a foul odor caused by

degradation of blood in the small intestine and colon.

The distinction between upper and lower GI bleeding

based on stool color is not always reliable. Hematochezia

(bright red blood or maroon color stools with clots), typical

of lower GI bleeding, also can occur in severe UGI bleeding.

Hematochezia in UGI bleeding is a sign of massive hemor-

rhage, and patients are usually orthostatic. In a recent series

of 80 patients with hematochezia, UGI bleeding was found in

11% of patients.

Initial Evaluation

Initial evaluation of a patient with overt GI bleeding starts

with hemodynamic status assessment, critical for proper

Gastrointestinal Bleeding

∗

∗

Tracey D. Arnell, MD, was the author of this chapter in the second

edition.

Copyright © 2008 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. Click here for terms of use.

CHAPTER 33

704

patient triage and timely resuscitation. Syncope or lighthead-

edness, when associated with GI bleeding, are classic signs of

hemodynamic compromise. Unstable vital signs or postural

hypotension indicates significant blood volume loss (>10%),

pointing to possibly massive bleeding (Table 33-1).

Following hemodynamic assessment, a focused history

and physical examination should be performed. Timing,

amount, and color of the blood; potential risk factors for GI

bleeding; and confounding comorbidities are the main

points to be elicited.

Repeated bleeding episodes or passage of bright red blood

or large blood clots indicates clinically significant bleeding.

In trying to identify potential risk factors, a detailed medica-

tion history is particularly important. Aspirin and non-

steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are the most

common causes of UGI bleeding. The risk appears to be

dose-related, but even patients taking low-dose (75 mg)

aspirin are at increased risk for bleeding. The risk is further

amplified when NSAIDs are taken along with corticosteroids

or bisphosphonates. Although data are limited, bleeding risk

also appears to be increased with clopidogrel. Chronic anti-

coagulation itself does not increase the risk for GI bleeding

but is thought to unmask preexisting causes of bleeding.

Particular attention should be paid to associated comor-

bidities. Confounding medical problems, in particular coro-

nary artery disease (CAD), chronic obstructive pulmonary

disease (COPD), and liver disease, affect subsequent resusci-

tative and treatment decisions. Moreover, with recent

advances in GI bleeding management, mortality mostly

results from decompensation of associated illnesses caused

by bleeding rather than from the bleeding itself.

Physical examination of a patient with GI bleeding should

focus on signs of hemodynamic instability and volume loss.

Rectal examination should be performed with attention to

stool color and presence of frank blood or melena. Stool

occult blood testing is not helpful in the acute setting.

Another important goal of the examination is to assess

the severity of comorbid medical conditions. For example,

ascites, spider angiomas, and abdominal wall collateral veins

indicate significant liver disease. Respiratory status should be

checked in all patients, particularly those with in COPD, to

determine sedation risk and the need for endotracheal intu-

bation prior to therapeutic interventions.

After initial resuscitation, physical examination usually is

followed by NG aspiration. Presence of blood in NG aspi-

rates confirms an upper GI source of bleeding, but a 10–15%

false-negative rate of NG aspiration has been reported, mostly

in patients with postpyloric bleeding lesions. Some experts

consider NG aspiration redundant if endoscopy is planned

within a few hours. However, finding of bright red blood in the

aspirate has been shown to correlate strongly with GI bleeding

mortality and is an independent predictor of rebleeding. NG

lavage also helps to clear blood and blood clots from the stom-

ach prior to endoscopy, improving diagnostic yield. To clear

the stomach prior to endoscopy, some experts also recom-

mend administration of a promotility agent such as erythro-

mycin (3 mg/kg intravenously). Cold water or saline lavage is

no longer recommended because it does not facilitate hemo-

stasis. Testing of NG aspirate for occult blood is notoriously

unreliable and should be discouraged.

The initial evaluation concludes with focused laboratory

tests, including hemoglobin, prothrombin time (PT) or inter-

national normalization ratio (INR), platelet count, and assess-

ment of renal and liver function. In patients with CAD (or high

risk for CAD), an ECG should be obtained. If chest pain or sig-

nificant ECG changes are present, cardiac biomarkers need to

be checked. Initial hemoglobin values often underestimate the

extent of blood loss because hemodilution can take up to

72 hours to occur. Thus initial hemoglobin can be misleading

in risk stratification decisions. A blood urea nitrogen

(BUN):creatinine (Cr) ratio of more than 36 may be seen in

UGI bleeding. Blood proteins are degraded by bacteria in the

upper intestinal tract and are absorbed as urea, thus increasing

BUN. The sensitivity of a BUN:Cr ratio of more than 36 for

UGI bleeding is about 90%, but specificity is quite low (~30%).

The results of the initial evaluation should provide answers

to two main questions: (1) Is bleeding moderate or massive,

based on the degree of hemodynamic compromise, and (2) is

there exacerbation of a comorbid illnesses by the bleeding?

Resuscitation

Resuscitation has a dual goal: (1) aggressively restore intravas-

cular volume and (2) optimize comorbid conditions in order

to decrease bleeding and minimize treatment-related compli-

cations. The degree of hemodynamic instability and associated

illnesses determines the extent of resuscitative measures and

monitoring. Older patients and patients with significant car-

diopulmonary disease or hemodynamic compromise should

be monitored in the ICU. For these patients, endoscopy should

be performed at the bedside in the ICU to optimize monitor-

ing. Patients with altered mental status or massive bleeding

should be electively intubated for airway protection. All

patients need two large (at least 18 gauge) intravenous

catheters placed or central venous access obtained.

Initial volume resuscitation should be done with normal

saline or lactated Ringer’s. Colloids can be given. In patients

Finding % Blood Loss

Shock 20–25%

Postural hypotension 10–20%

Normal <10%

Modified from Feldman M et al: Sleisenger and Fordtran’s

Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2003,

p. 212.

Table 33–1. Gastrointestinal bleeding: vital signs and

blood loss.

GASTROINTESTINAL BLEEDING

705

with cardiopulmonary, renal, or liver disease, central venous

monitoring can be helpful to monitor volume status closely.

Concurrently with intravascular volume resuscitation,

any hemostatic abnormalities need to be corrected. A target

level for INR of less than 1.5 and platelet count greater than

50,000/μL should be sought when active GI bleeding is

occurring. Appropriate clotting factors, usually in the form

of fresh-frozen plasma, are given to achieve rapid reversal of

coagulopathy. Even if deficient, vitamin K typically does not

correct a coagulopathy fast enough and should be used only

as an adjunct to clotting factors.

Transfusion of packed red blood cells is usually consid-

ered when hemoglobin is less 10 g/dL, especially in patients

with cardiopulmonary disease. Clinical data supporting this

threshold value are limited. However, maintaining the hemo-

globin level above 10 g/dL showed a trend toward improved

survival in critically ill patients with CAD. Aiming at a hemo-

globin level of greater than 8 g/dL appears to be safe for

young, healthy patients without comorbidities.

Risk Stratification

Initial evaluation and the patient’s response to resuscitation

determine patient risk, and patients can be stratified into high-

or low-risk categories for rebleeding and mortality. Indeed,

80% of patients with UGI bleeding stop bleeding without

treatment. It is crucial to identify the remaining 20% who are

at increased risk for continued bleeding and mortality.

Multiple scoring systems have been proposed based on both

clinical and endoscopic criteria. Because physicians typically

determine risk prior to endoscopy, risk stratification schemes

based on clinical parameters alone are most practical.

Predictors of rebleeding and mortality are age greater

than 65 years, shock, comorbid illnesses, bright red blood per

rectum or in the emesis, low initial hemoglobin, and high

transfusion requirements. For example, a scoring system that

has been prospectively validated recently includes initial vital

signs, presence of syncope or melena, hemoglobin, BUN, and

presence of hepatic or cardiac disease. This system correctly

identified up to 99% of patients with serious bleeding and

more than 20% of low-risk patients who were further man-

aged as outpatients. However, because such risk stratification

schemes mostly come from cohort studies, concerns remain

about their prospective validity.

We use a simple risk stratification system based on

patient age, orthostatic changes in blood pressure or heart

rate or syncope, history of cardiopulmonary or liver disease,

and fresh blood in emesis or NG aspirate. Patients with these

clinical predictors are considered to be at high risk for con-

tinued bleeding and mortality. Such patients require ICU

monitoring and endoscopy in the ICU immediately after

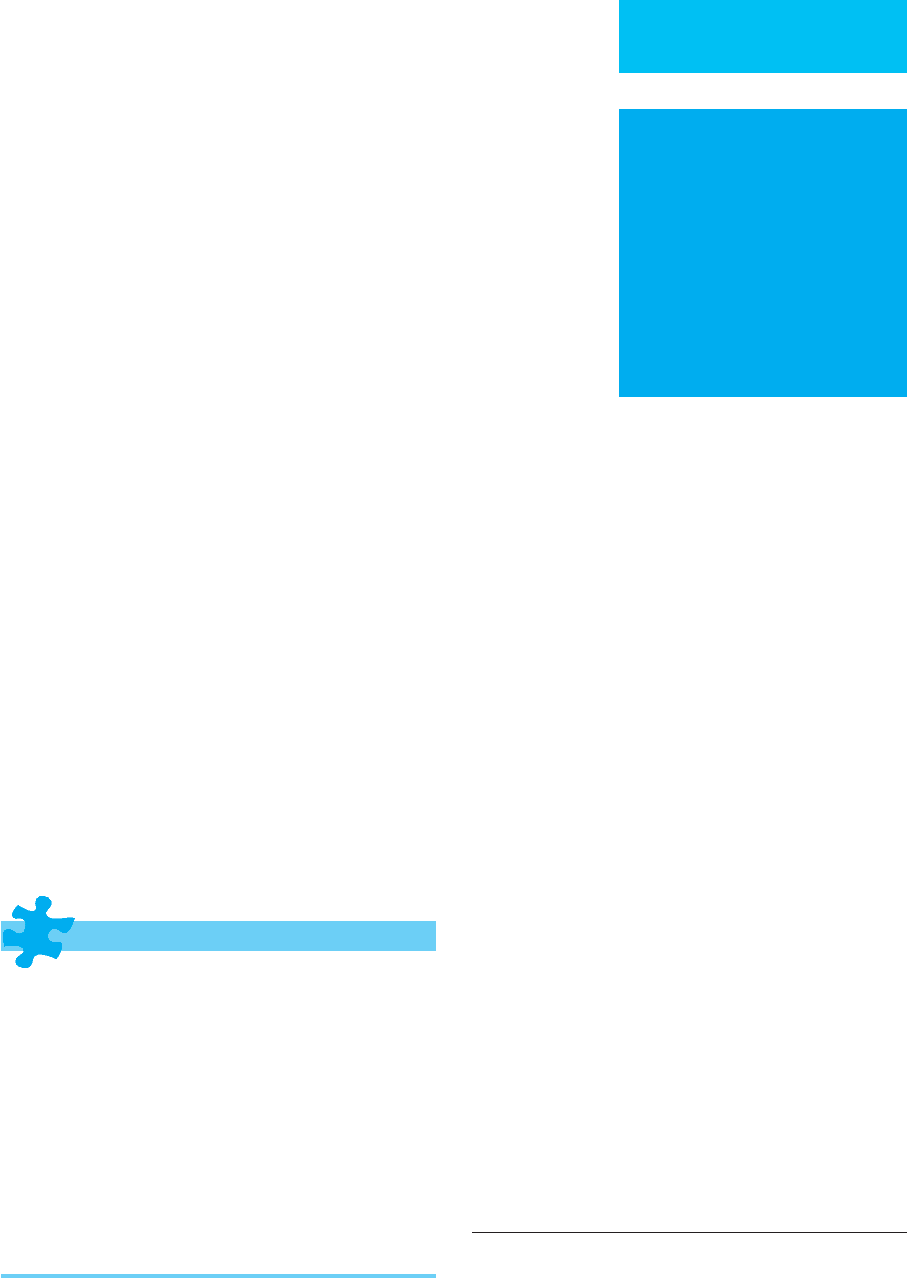

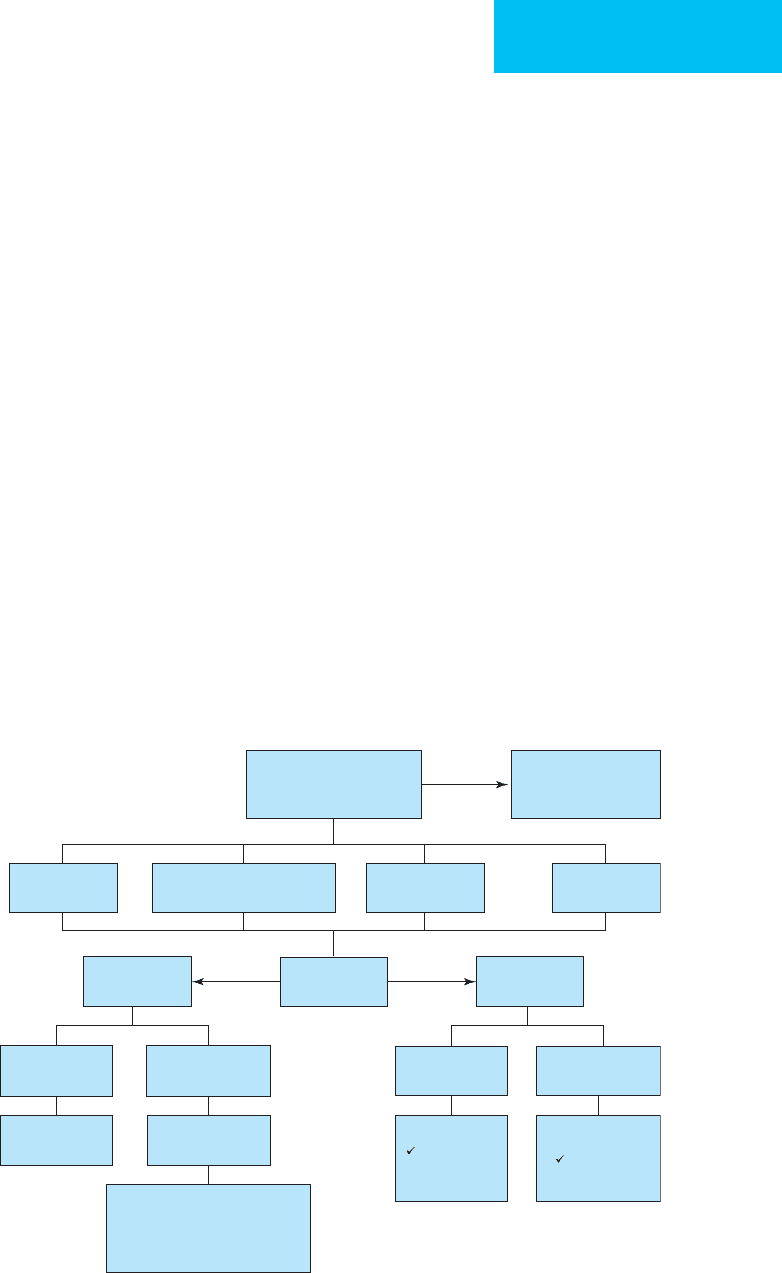

resuscitation is completed (Figure 33–1). In life-threatening

hemorrhage, when patients fail initial resuscitation, we per-

form endoscopy in the operating room with surgical service

backup rather than delaying endoscopy with repeated resus-

citation attempts.

Non-variceal

bleeding

Endoscopic

therapy

Endoscopic

therapy

Gastric

PPI IV

H. pylori

Inpatient

48–72 h

PPI PO

H. pylori

Early discharge

Hematemesis

Melena

Coffee-ground emesis

Older age

Syncope

Orthostatic hypotension

Fresh blood in

NG aspirate

Liver disease

CAD

No endoscopic

therapy

TIPS

IV octreotide, 3–5 days

antibiotics

IV PPI

Repeat EGD in 2–3 weeks

Variceal

bleeding

IV fluids, blood

IV PPI

± Octreotide/FFP

Urgent

endoscopy

Esophageal

Figure 33–1. Management of upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

CHAPTER 33

706

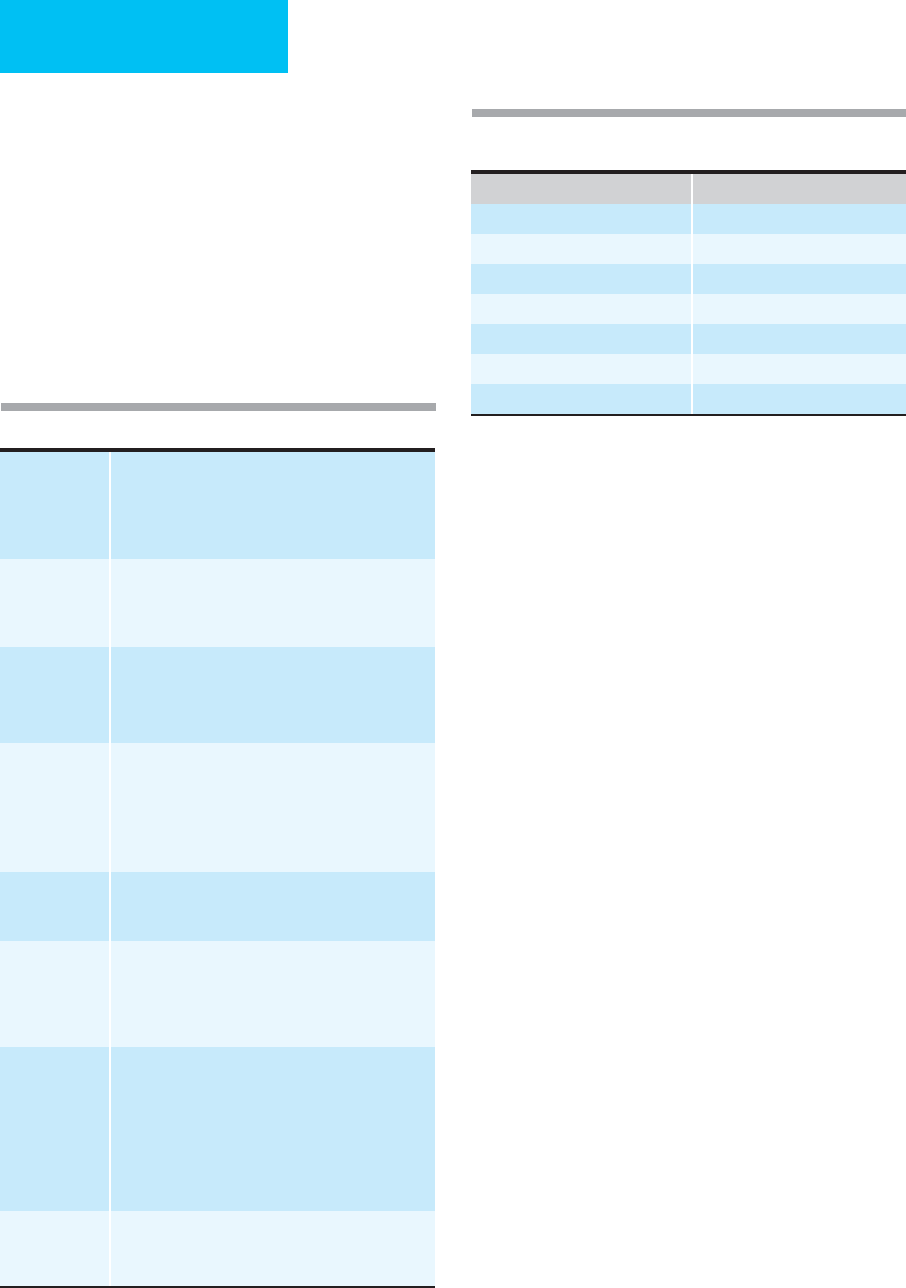

Causes of UGI Bleeding

Causes of acute UGI bleeding can be grouped into six main

categories based on anatomic and pathophysiologic parame-

ters: ulcers or erosions, portal hypertension, vascular lesions,

trauma, tumors, and miscellaneous (Table 33–2). For

decades, peptic ulcer disease has been the most common

cause of UGI bleeding, followed by esophageal varices.

Recently, the trends have changed (Table 33–3). The latest

review of the Clinical Outcomes Research Initiative (CORI)

database showed that peptic ulcer disease accounts for fewer

than 21% of UGI bleeding episodes. Nowadays, the most

common cause is nonspecific mucosal abnormalities (such

as erosions), responsible for 42% of UGI bleedings. This

changing dynamic is most likely brought about by wide-

spread use of NSAIDs and by increased recognition and treat-

ment of Helicobacter pylori infection.

A. Peptic Ulcer Disease—Peptic ulcer disease can be a

result of H. pylori infection, NSAID use, stress, or excess gas-

tric acid exposure. H. pylori is a spiral gram-negative bac-

terium found in 90% of duodenal ulcers and 70% of gastric

ulcers. It is thought to be transmitted via the fecal-oral route

and is commonly acquired in early childhood. H. pylori does

not typically invade mucosa but makes mucosa more suscep-

tible to gastric acid damage. It also stimulates host immune

response, resulting in chronic inflammation (gastritis) and

further mucosal damage. Most infected individuals are

asymptomatic, but in some, chronic inflammation and

increased gastric acid secretion lead to ulcer formation.

NSAIDs are another common cause of gastroduodenal

ulceration. Aspirin and NSAIDs are prescribed very often,

and their use is particularly widespread in the elderly because

of aspirin’s cardioprotective effects and the role of NSAIDs in

osteoarthritis management. Until recently, NSAID-related

injury was thought to be limited primarily to the stomach

and duodenum. Later reports showed that NSAIDs are also a

common cause of distal small bowel and even colonic ulcer-

ation. NSAID-induced mucosal injury results from both

direct topical and systemic effects of prostaglandin inhibi-

tion. NSAIDs also can be a contributing factor to nonhealing

ulcers from other causes. Although erosions and small ulcer-

ations are found frequently in NSAID users, most patients

are asymptomatic. The risk of clinically significant ulceration

and bleeding with chronic NSAID treatment is about 1%.

Peptic ulceration also commonly occurs with severe

stress, including major trauma, burns, sepsis, and multiorgan

system failure. The injury is likely the result of impaired

mucosal defense mechanisms secondary to decreased

mucosal blood flow. Over the past decade, the incidence of

stress-induced ulcer bleeding has been declining, with the

recently reported rate in critically ill patients only 1.5%. The

Cause Relative Frequency

Mucosal abnormalities 37%

Peptic ulcer disease 21%

Esophagitis 15%

Varices 12%

AVM 6%

Mallory-Weiss tear 5%

Tumors 4%

Table 33–3. Common causes of upper gastrointestinal

bleeding.

Table 33–2. Causes of upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

Ulcerative

erosive

Peptic ulcer disease

Infectious (

H. pylori

, CMV)

NSAIDs, ASA

Stress-induced

Zollinger-Ellison syndrome

Esophagitis

Peptic

Infectious (

Candida

, HSV, CMV)

Pill-induced (alendronate, ASA, NSAIDs, tetracycline)

Portal

hypertension

Varices

Esophageal

Gastric

Portal hypertensive gastropathy

Vascular

malformation

Arteriovenous malformations

Idiopathic angiomas

Osler-Weber-Rendu syndrome

Dieulafoy’s lesion

Radiation-induced telangiectasia

Gastric antral vascular ectasia

Traumatic,

postoperative

Mallory-Weiss tear

Foreign body

Aortoenteric fistula

Tumors Benign

Leiomyoma

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors

Lipoma

Polyps (adematous, inflammatory)

Malignant

Adenocarcinoma

GI stromal tumor

Sarcomas

Lymphoma

Carcinoid

Melanoma

Kaposi’s sarcoma

Miscellaneous Hemobilia

Hemosuccus pancreaticus

Meckel’s diverticulum