Bongard Frederic , Darryl Sue. Diagnosis and Treatment Critical Care

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

467

0021

Cardiac Problems

in Critical Care

Shelley Shapiro, MD, PhD

Malcolm M. Bersohn, MD, PhD

Critically ill patients can present challenging cardiac prob-

lems for both diagnosis and management. Many critically ill

patients develop cardiac problems secondary to the metabolic

and hemodynamic consequences of their underlying illness.

Others have preexisting cardiac conditions that are either well

compensated or asymptomatic prior to presentation to the

ICU and become clinically relevant during their ICU course.

A final group of patients is treated in the ICU for known car-

diac conditions or has their heart condition diagnosed during

their ICU admission. In all of these patients, the interplay of

the cardiac illness with other medical problems critically

influences the patient’s outcome. Therefore, defining the type

and severity of the underlying cardiac problem, considering

their relationship to other medical problems, and treating the

heart disease are important considerations. As always, the key

factor in the management of cardiac problems is a high

degree of suspicion and early diagnosis. Methods for identify-

ing and diagnosing cardiac disease in critically ill ICU

patients will be emphasized throughout this chapter.

Congestive Heart Failure

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Cardiomegaly, decreased ventricular ejection fraction or

abnormal ventricular wall motion, elevated pulmonary

artery wedge pressure, low cardiac output.

May have a previously known cause such as valvular heart

disease or cardiomyopathy but also may present as a result

of ischemia or secondary to severe systemic hypertension.

Acute pulmonary edema: dyspnea, orthopnea, rales,

and wheezing; abnormal chest x-ray with perihilar con-

gestion; hypoxemia.

Cardiogenic shock: hypotension; abnormal renal,

hepatic, and CNS function due to decreased perfusion;

lactic acidosis.

General Considerations

Congestive heart failure is a major therapeutic and diagnos-

tic challenge because of the number of its possible causes, the

number of patients who have heart failure, and the associ-

ated disability. Congestive heart failure is the most frequent

diagnostic category coded in Medicare patients. Determining

the cause and severity of congestive heart failure is extremely

important for effective treatment. Although coronary artery

disease is a frequent cause of congestive heart failure, partic-

ularly in the elderly, there are many other causes. For exam-

ple, congestive heart failure with pulmonary edema

secondary to mitral stenosis is managed quite differently

from that due to dilated cardiomyopathy. Therapy effective

in treating congestive heart failure in a patient with severe

mitral regurgitation could be lethal in a patient with critical

aortic stenosis. With the ability to perform valve replace-

ment and repair, coronary bypass grafting and angioplasty,

and the possibility of cardiac transplantation, a specific car-

diac diagnosis has implications for interventional manage-

ment as well as drug therapy.

The causes of chronic congestive heart failure may be very

different from the causes of acute failure. Acute congestive

heart failure in critically ill patients is due to myocardial

ischemia or infarction, acute valvular insufficiency (eg, mitral

or aortic regurgitation), worsening aortic stenosis or mitral

stenosis, acute myocarditis (rare), cardiotoxic drugs, alcohol,

and sepsis. Often, volume overload (owing to fluid volume

administered in the ICU for treatment of hypotension or as

part of administration of therapy for other disease processes)

precipitates heart failure in the ICU setting. This may be com-

pounded by anemia and/or by reduced renal function result-

ing in additional fluid retention and volume expansion. The

role of excessive fluid resuscitation and accumulating vol-

ume overload in ICU patients cannot be too highly empha-

sized. Hypoalbuminemia also can add to the picture by

allowing fluid to transudate at lower oncotic pressures.

Recently, a new acute form of heart failure has been

described in patients suffering acute severe stress resulting in

Copyright © 2008 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. Click here for terms of use.

CHAPTER 21

acute severe myocardial dysfunction (mimicking myocardial

infarction or acute cardiomyopathy). This syndrome, more

common in females, appears to be reversible but presents as

life-threatening heart failure. Chronic congestive heart fail-

ure is often idiopathic, although in many cases it is associated

with ischemic heart disease, chronic valvular heart disease,

and hypertension. The additional stress of the ICU and asso-

ciated critical illness may worsen preexisting myocardial dys-

function and heart failure in a previously stable patient.

A high degree of suspicion of congestive heart failure is

required to identify subtle cases or patients with coexisting

heart failure. Patients in the ICU with dyspnea and hypox-

emia often have combined heart and lung disease, and

patients with known pulmonary disease can develop cardiac

disease as a result of the increased stress of sepsis, hypoxia, or

deterioration of pulmonary function. Any patient with unex-

plained hypoxemia, hypotension, or a worsening clinical

state requires assessment of cardiac function.

A. Cardiac Function in the Normal Heart—Cardiac out-

put is the product of stroke volume and heart rate. Stroke

volume is determined by three factors: preload, afterload,

and contractility. In the intact heart, preload is the end-

diastolic tension or wall stress and is ultimately determined

by the resting length of the muscle or the degree of stretch of

the muscle fibers. Preload is directly related to the compli-

ance of the ventricle and the end-diastolic pressure.

Although preload is a measure of force, in conceptual terms

it can be thought of as being most closely related to the end-

diastolic volume of the ventricle. As the ventricular volume

and pressure increase, so does the preload. Pulmonary capil-

lary wedge pressure is often used when clinically describing a

patient’s preload.

Afterload is the resistance against which the ventricle

ejects blood. Afterload or tension on the left ventricle can be

described by the formula ΔP × r/h, where ΔP is the trans-

mural pressure during ejection, r is the radius of the left ven-

tricular chamber, and h is the thickness of the ventricular

wall. Stroke volume is inversely proportional to afterload.

Contractility is the inherent ability of the muscle to con-

tract and is independent of the loading conditions on the heart

(ie, preload and afterload). Circulating catecholamines and

increased sympathetic efferent activity increase contractility.

Cardiac performance can be improved for a given level of

myocardial contractility by changing the loading conditions.

B. Cardiac Function in Congestive Heart Failure—

Congestive heart failure develops when cardiac function is

inadequate to maintain sufficient cardiac output to supply

the metabolic needs of the body at normal filling pressures

and heart rate. In mild heart failure, cardiac function may

be adequate at rest. However, exercise or illness can

increase metabolic demands that may not be met when

cardiac reserve is inadequate. Thus congestive heart failure

may be precipitated by critical illness with attendant fever,

anemia, and vasodilation. In heart failure owing to

decreased left ventricular function with reduced stroke vol-

ume, cardiac output may be transiently maintained by

increased heart rate or by increased preload with ventricu-

lar dilation and increased volume. The increasing use of

beta-blockers in the treatment of chronic congestive heart

failure, ischemia, and chronic coronary artery disease may

blunt the sympathetic response and tachycardia necessary

to maintain cardiac output. Acutely, however, cardiac out-

put may be insufficient, and signs and symptoms of hypop-

erfusion including hypotension, cyanosis, and peripheral

vasoconstriction, may be present (forward failure).

Inadequate ventricular emptying (low forward flow) results

in elevated left atrial and left ventricular end-diastolic vol-

ume and pressure that are transmitted back into the lungs

and the pulmonary venous system with transudation of

fluid. Clinically, this is manifested by rales, hypoxemia, and

dyspnea (backward failure).

A number of neurally and hormonally mediated

responses develop in an attempt to compensate for inade-

quate cardiac performance. These compensatory responses

include renal-mediated fluid retention and peripheral vaso-

constriction, tachycardia, and ventricular dilation which

attempt to maintain systemic blood pressure and cardiac out-

put. However, these compensations frequently are counter-

productive and worsen hemodynamic status. For example,

vasoconstriction, while maintaining systemic blood pressure,

increases ventricular afterload, ultimately decreasing stroke

volume and cardiac output; fluid retention increases preload

(improving stroke volume), but it also raises pulmonary

venous pressure and is detrimental to oxygenation and gas

exchange. Tachycardia increases cardiac output but also

increases myocardial oxygen demand which is particularly

devastating in the setting of myocardial ischemia and

decreases diastolic time needed for optimal ventricular fill-

ing, which is particularly problematic in patients with dias-

tolic dysfunction (problems with ventricular stiffness).

It is now well recognized that vasoconstriction and tachy-

cardia, previously considered compensatory and useful to

the patient, play important roles in the progression of con-

gestive heart failure. This is why afterload-reduction therapy

with angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or

other vasodilating agents and aggressive diuretic therapy have

greatly improved survival in this disorder. Beta-adrenergic

blockade in stable patients with compensated heart failure is

useful and prolongs life by decreasing the disadvantageous

effects of adrenergic stimulation. The benefit of beta-blockers

must be weighed against worseing heart failure and should

be withheld until heart failure is well controlled.

Clinical Features

A. Symptoms and Signs—Patients with congestive heart

failure may develop symptoms slowly or acutely. They may

complain of peripheral edema or of congestive symptoms

such as dyspnea, orthopnea, or paroxysmal nocturnal dysp-

nea. Symptoms consistent with decreased cardiac output

468

CARDIAC PROBLEMS IN CRITICAL CARE

469

include fatigue and exercise intolerance. Chest pain may be a

feature of acute-onset congestive heart failure associated

with myocardial ischemia, infarction, or severe hypertension.

Because of sedation and decreased activity in the critical care

setting, ICU patients may not complain of any symptoms at

all. An increasing heart rate, decreasing oxygen saturation, or

increasing oxygen requirement may be the only clues.

Patients who present with acute pulmonary edema may

have pink frothy sputum, rales, expiratory wheezes, and cen-

tral along with peripheral cyanosis. Tachycardia and

hypotension are manifestations of decreased cardiac output;

in these patients, low output may be accompanied by periph-

eral vasoconstriction, with peripheral cyanosis, cold extrem-

ities, and diaphoresis. In patients in whom severe systemic

hypertension is causally related to congestive heart failure,

blood pressure may be high despite low cardiac output. In

patients with cardiogenic shock, hypotension is accompa-

nied by evidence of very poor peripheral perfusion. On

examination, patients with dilated cardiomyopathy may have

an S

3

gallop, a murmur consistent with mitral regurgitation,

and elevated jugular venous pressure. Other findings depend

on the specific cause and may include murmurs consistent

with valvular heart disease and an S

4

gallop. However, in an

ICU setting, many of the findings may be blunted or difficult

to appreciate. Patients with long-standing chronic heart fail-

ure may have high filling pressures and severe heart failure

without the development of rales or an S

3

owing to the devel-

opment of chronic pulmonary hypertension and other com-

pensatory mechanisms. They are in heart failure nevertheless

and respond to appropriate therapy once the diagnosis is

established.

B. Laboratory Findings—Patients may present with hypox-

emia, metabolic acidosis from lactic acidosis, and hypona-

tremia. In patients with hypotension or shock, renal and

hepatic function tests may be abnormal.

C. Electrocardiography—The ECG should be examined for

evidence of myocardial ischemia or infarction, atrial hyper-

trophy, and ventricular hypertrophy. Rhythm disturbances

(eg, atrial fibrillation or flutter) may be a cause or an effect

of congestive heart failure. Patients with dilated cardiomy-

opathy or severe left ventricular hypertrophy owing to

hypertension or hypertrophic processes may have conduc-

tion or voltage abnormalities consistent with left ventricular

hypertrophy. Tachycardia may indicate poor hemodynamic

performance.

D. Imaging Studies—

1. Chest x-ray—Chest x-ray may show cardiomegaly in

patients with dilated or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

However, patients with valvular heart disease may have only

a mild increase in heart size or isolated chamber enlarge-

ment. Ventricular dilatation may not be present in acutely

developing heart failure and therefore not seen on x-ray.

Cardiogenic pulmonary edema is usually marked by central

or perihilar infiltrates, increased size of vessels serving the

upper portions of the lungs in the upright position, and

increased prominence of interlobular septa—usually bilat-

eral and symmetric. Pleural effusions are common. Chest

x-rays are very important to exclude pulmonary disease that

may mimic heart failure, in particular acute respiratory

distress syndrome (ARDS) and severe pneumonia.

2. Echocardiography—Noninvasive testing, particularly

in a critically ill patient, may be difficult but gratifying if suc-

cessful in identifying a treatable cause of congestive heart

failure. Echocardiography, because of its portability, repro-

ducibility, and ability to evaluate myocardial and valvular

function, is a valuable tool in the assessment of ICU

patients. Hemodynamic data, including an estimate of right

ventricular pressure, left atrial pressure, valve areas, left ven-

tricular ejection fraction, and ventricular volumes, can be

obtained at the bedside if image quality is adequate. Cardiac

output can be estimated with echo Doppler using the conti-

nuity equation. Myocardial ischemia can be inferred by

identification of segmental wall motion abnormalities at

rest or during special interventions designed to bring out

abnormalities in ischemic regions. Dobutamine or adeno-

sine infusion can be performed with echocardiography and

ECG monitoring to obtain a bedside stress test. Pericardial

effusions can be diagnosed and measured and their hemo-

dynamic impact evaluated. Echocardiography is a sensitive

technique for diagnosing cardiac tamponade. Assessment of

valvular regurgitation and monitoring the response to ther-

apy are other uses for echocardiography.

Echocardiography is technically difficult in about 10% of

patients overall. Although echo-enhancing contrast agents can

improve image quality, ICU patients, because they are often

mechanically ventilated and have multiple intravenous or cen-

tral lines in place, are difficult to position ideally and often are

more difficult to image properly with echocardiography.

Transesophageal technology has increased the value of echocar-

diography by providing images of good quality in patients who

have had inadequate transthoracic studies. With trans-

esophageal echocardiography, the heart is imaged via a trans-

ducer inserted into the esophagus through the mouth. The close

proximity of the esophagus to the left atrium provides an excel-

lent acoustic window resulting in better images. Views unob-

tainable with conventional transthoracic echocardiography are

possible with this technique. The pulmonary veins, both atrial

appendages, and the ascending and descending aorta can be well

imaged in addition to the ventricles and valves.

3. Radionuclide angiography—Radionuclide angiogra-

phy can measure right and left ventricular ejection fractions

and evaluate wall motion. Myocardial uptake of technetium

pyrophosphate at times can be useful to identify myocardial

infarction or cardiac contusions. A number of radionuclide

techniques are used to assess coronary artery disease. These

studies are not performed at bedside and are of no utility in

ICU patients.

CHAPTER 21

470

4. CT scan—In patients who can be moved to the scanner,

CT scanning provides high-resolution tomographic imaging

of the heart and great vessels and can assess right and left

ventricular size. CT scans also can assess lung parenchyma to

rule out a primary pulmonary process and differentiate con-

gestive heart failure from other lung diseases. With the use of

contrast material, pulmonary thromboembolism or proxi-

mal pulmonary artery thrombosis can be seen with spiral CT

scanning (CT angiogram).

5. Cardiac catheterization/pulmonary artery

catheterization—When noninvasive studies cannot

fully answer questions about cardiac function, bedside

balloon-tipped flow-directed (Swan-Ganz catheter) pul-

monary artery catheterization is performed. The catheter is

used to measure a variety of hemodynamic parameters,

including left ventricular end-diastolic pressure (pul-

monary artery wedge pressure) and thermodilution cardiac

output. Newer modified catheters can continuously meas-

ure cardiac output and oxygen saturation. The catheter is

placed transvenously into the pulmonary artery by way of

the right atrium and right ventricle, usually without fluoro-

scopic guidance. The catheter is often of critical importance

in defining cardiac function and differentiating cardiac

from pulmonary disease in patients with pulmonary infil-

trates and dyspnea. The pulmonary artery catheter is par-

ticularly useful for monitoring the effect of intravenous

drugs on hemodynamics when cardiac output is low. In

patients with acute severe congestive heart failure, the goal

is to maximize cardiac output while lowering wedge pres-

sure in order to relieve pulmonary edema.

In selected patients, left-sided heart catheterization allows

direct measurement of left ventricular pressures and func-

tion, imaging of the coronary arteries to rule out critical

obstruction, and angiographic measurement of cardiac out-

put and left ventricular ejection fraction. Left-sided heart

catheterization requires fluoroscopy and cannot be done in

most ICUs.

Differential Diagnosis

Patients with clinical features of congestive heart failure pre-

senting with dyspnea, orthopnea, rales, and wheezing instead

may have pneumonia, ARDS, fluid overload, or exacerbation

of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or

asthma. Cardiomegaly may be due to ventricular hypertro-

phy, right ventricular dilatation, or pericardial effusion

rather than an enlarged left ventricle itself. In patients who

present with symptoms and signs of primarily right-sided

heart failure—such as elevated jugular venous pressure,

ascites, edema, and evidence of right ventricular hypertrophy—

lung disease resulting in cor pulmonale, or pulmonary arte-

rial hypertension (eg, pulmonary arteriopathy, idiopathic or

secondary pulmonary arterial hypertension, or pulmonary

emboli) should be considered. Patients with hypotension

from cardiac failure should be distinguished from those with

volume depletion, sepsis, and pulmonary embolism.

Treatment

A. General Measures—After determining the underlying

cause of congestive heart failure, treatment in the ICU con-

sists of quickly reversing the hemodynamic problem without

adding further ones. In very ill patients, initial management

of congestive heart failure should use intravenous medica-

tions. In this form, medications can be titrated rapidly and

stopped quickly if necessary. Intravenous administration of

drugs guarantees absorption, particularly in patients with

bowel edema and decreased bowel motility. Although some

intravenous agents have long half-lives and slow onsets of

action, nitroprusside, nitroglycerin, nesiritide, dopamine,

dobutamine, and milrinone act quickly and are easily reversed.

Cardiogenic shock may require the initial or concomitant

use of vasopressor drugs such as dopamine and inotropic

drugs such as dobutamine or milrinone to allow the institu-

tion of afterload-reduction therapy. Nitroprusside is a potent

reducer of left ventricular afterload and is particularly valu-

able in treating severe congestive heart failure. Disadvantages

include toxicity in patients with renal insufficiency who are

given nitroprusside over a prolonged period of time.

Intravenous preparations of ACE inhibitors are effective and

have longer durations of action. Digoxin and diuretics are still

important despite development of newer classes of drugs.

Because of negative inotropic effects, calcium channel block-

ers and beta-blockers are used with extreme caution, if at all,

in patients with acute congestive heart failure. Occasionally,

however, congestive heart failure may be secondary to tach-

yarrhythmias, left ventricular diastolic dysfunction, or severe

transient ischemia, and these drugs then play an important

role. Close hemodynamic monitoring, usually with a pul-

monary artery catheter, allows the physician to titrate multi-

ple drugs optimally. In cases of severe cardiogenic shock with

low cardiac output, use of mechanical devices including

intraaortic balloon pump or left ventricular assist devices is a

consideration. The use of these devices involves decisions

regarding long-term treatment options, prognosis, and

underlying disease etiologies. The decision to intervene at this

level requires consultation with a cardiac catheterization team

and the heart transplant team or heart failure specialists.

General treatment of congestive heart failure in critically

ill patients includes oxygen, bed rest, and reduction of meta-

bolic derangements that increase myocardial oxygen demand

(eg, fever and anemia). Endotracheal intubation and

mechanical ventilation usually are not necessary, except in

severe cardiogenic pulmonary edema.

B. Specific Treatment of Congestive Heart Failure—

Patients with congestive heart failure can be subdivided into

several groups for which specific treatments can be described

as follows:

1. Systolic dysfunction without hypotension—These

patients have low stroke volumes and ejection fractions and

usually have tachycardia. Pulmonary edema may accompany

systolic dysfunction. Digoxin, diuretics, and ACE inhibitors are

the mainstays of therapy. Several studies have shown that ACE

CARDIAC PROBLEMS IN CRITICAL CARE

471

inhibitors prolong life in patients with chronic congestive heart

failure owing to left ventricular dysfunction and in patients

with myocardial infarction associated with reduced left ventric-

ular function. If the patient is felt to be stable enough to toler-

ate oral therapy, small doses of an ACE inhibitor and digoxin

can be initiated. Hypotension may accompany ACE inhibitor

therapy if cardiac output fails to increase after vasodilation, and

inotropic drug support of blood pressure may be required.

Withholding or reducing the dosage of diuretics when ACE

inhibitors are added often can prevent the development of

hypotension. Serum creatinine and potassium levels must be

observed carefully because of the effect of ACE inhibitors on

renal function (particularly in patients with renal artery steno-

sis) and on the renin-aldosterone system.

Diuretics are useful in reducing volume overload, partic-

ularly when signs of right-sided failure such as peripheral

edema, elevated jugular venous pressure, and liver engorge-

ment are present. Intravenous furosemide can be given in a

dose of 10–80 mg (more in patients with poor response) and

repeated as needed. Continuous infusion of furosemide at a

rate of 5–10 mg/h is also effective. Metolazone or

hydrochlorothiazide can augment the effectiveness of

furosemide by further inhibiting reabsorption of sodium.

Sustained diuresis with any of these agents is associated with

significant loss of potassium and magnesium. Nesiritide is a

recombinant human B-type natriuretic peptide that is indi-

cated for intravenous treatment of acutely decompensated

congestive heart failure. It is given as an initial bolus of 2 μg/kg,

followed by continuous infusion of 0.01 μg/kg per minute

for less than 48 hours. Hypotension is a known side effect.

Spironolactone has been shown to decrease mortality in

chronic congestive heart failure and can be added to help

spare potassium loss in the acute situation. Finally, patients

in severe congestive heart failure with renal dysfunction may

be unable to excrete large amounts of sodium and water, so

ultrafiltration may be needed to correct volume overload.

Newer devices allow removal of fluid at rates up to 400 mL/h

using specially designed 18-gauge peripheral lines and there-

fore eliminate the need for a large-bore vascular catheters.

However, if electrolyte abnormalities and renal dysfunction

compound the volume overload, dialysis may be required.

Noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation using tight-fitting

masks can be useful in acute pulmonary edema. A significant

reduction in the need for mechanical ventilatory support has

been demonstrated in patients present with acutely decompen-

sated congestive heart failure with the use of this noninvasive

form of ventilation compared to standard therapy. It appears

that the positive-pressure breathing lowers preload and left

ventricular afterload, improves oxygenation, and provides time

for pharmacologic therapy to work.

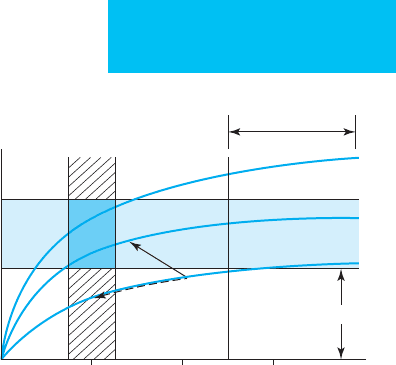

The effect of various drugs on filling pressures and cardiac

output can be demonstrated on the Frank-Starling curve

(Figure 21–1). Both digoxin and afterload-reducing agents

improve the patient’s cardiac output or stroke volume for a

given filling pressure (move the patient to a more effective

curve). In contrast, diuretics lower the left ventricular filling

pressure, relieving symptoms of dyspnea, but they also may

reduce cardiac output. The patient moves down along the

same function curve. Optimal treatment, therefore, should use

agents that move the patient to a better function curve, and

diuretics are employed to help lower filling pressures—if

they remain elevated—and to expedite symptomatic improve-

ment. In some patients with mild to moderate congestive heart

failure, bed rest alone will result in significant diuresis. In addi-

tion, improvement of cardiac output with afterload-reducing

agents and digoxin ultimately will result in diuresis. On the

other hand, both preload- and afterload-reducing agents can

result in venodilation and thus fluid retention, so diuretics

may be needed to counteract this unwanted side effect.

Although major emphasis has been placed on ACE

inhibitors in the treatment of chronic congestive heart fail-

ure, other drugs are effective, including preload-lowering

agents such as nitrates and afterload-reducing agents such as

hydralazine. For example, the combination of hydralazine

and nitrates has been shown to prolong life in patients with

chronic congestive heart failure.

2. Severe congestive heart failure with hypotension

(cardiogenic shock)—Patients with severe congestive

heart failure associated with hypotension, pulmonary

edema, and metabolic acidosis require aggressive and immediate

10 20 30

End-diastolic pressure (mm Hg)

Low output

1

2

3

Pulmonary edema

Normal

Stroke volume

Normal

Figure 21–1. Curves demonstrating the relationship

between stroke volume and left ventricular end-diastolic

pressure (preload) and showing the normal range for each

variable. End-diastolic pressures greater than 25 mm Hg

are associated with pulmonary edema. Curve 1 represents

severely depressed left ventricular function, with normal

stroke volume being achieved only at substantially ele-

vated preload (high left ventricular end-diastolic pressure).

Curve 2 demonstrates a normal relationship between

stroke volume and preload. Curve 3 represents a condition

of increased inotropy. Treatment with afterload-reducing

agents or inotropic drugs can improve stroke volume by

moving an individual from curve 1 to curve 2 (solid

arrow). Diuretics can lower filling pressure by moving a

patient along his or her own curve (dashed arrow).

CHAPTER 21

472

intervention. These patients often have some reason for acute

deterioration such as ischemia, myocardial infarction, new or

worsening valvular insufficiency, poor adherence to medical

therapy, volume overload, or concomitant medical problems.

Even before invasive hemodynamic monitoring is instituted,

hemodynamic support can be started using intravenous

agents. With severe hypotension, blood pressure support is

required—intravenous dopamine should be administered in

dosages titrated to achieve a systolic blood pressure of approx-

imately 90 mm Hg or greater. An exception to this precept

would be a patient with cardiomyopathy whose known systolic

blood pressure is chronically 80 mm Hg. In such cases, clinical

markers of hypoperfusion such as decreased mental status or

acidosis should help to determine the appropriate blood pres-

sure goal. The inotropic drugs dobutamine and milrinone can

be used in conjunction with or as an alternative to dopamine to

increase cardiac output. Dobutamine has the further advantage

of peripheral vasodilation with reduction in left ventricular

afterload.

In patients with either adequate blood pressure (systolic

blood pressure >100 mm Hg) or even marginal pressure (sys-

tolic pressure 90–100 mm Hg), nitroprusside can be started at

small dosages (0.01–0.1 μg/kg per minute) and titrated upward

every 3–5 minutes while blood pressure is observed closely.

Although these are low starting doses, they may avoid the signif-

icant and rapid hypotension that sometimes occurs with larger

doses, and rapid dose adjustments make it possible to reach the

effective dose in a relatively short period. The goal of reducing

left ventricular afterload with nitroprusside is to increase cardiac

output. However, if peripheral resistance drops in response to

nitroprusside without an increase in cardiac output, hypoten-

sion will occur. The drop in blood pressure following nitroprus-

side administration can be dealt with by immediately

discontinuing the drug and providing inotropic support if

needed. The extremely short half-life of intravenous nitroprus-

side makes this a safe and valuable agent to try even before inva-

sive hemodynamic monitoring can be started.

Loop diuretics are also extremely valuable in this setting if

marked volume overload (pulmonary edema) is evident, as

furosemide causes a lowering of preload even before diuresis

occurs. Intravenous furosemide can be given in a dose of 10

to 40 mg (more in patients with poor response) and can be

repeated as needed. Continuous infusion of furosemide at a

rate of 5–10 mg/h is also very effective. Intravenous nitroglyc-

erin has preload-reducing as well as some afterload-reducing

properties and can be used alone or in conjunction with

intravenous nitroprusside to improve cardiac output and

reduce left-sided pressures. Nesiritide must be used with cau-

tion in cardiogenic shock to avoid worsening of hypotension.

Intraaortic balloon pumps and left ventricular assist

devices have been used to treat patients with extreme cardio-

genic shock. They are used acutely to allow time to explore

opportunities for additional interventions including angio-

plasty, cardiac surgery, or heart transplantation. This level of

tertiary management is undertaken in referral centers with

appropriate equipment, resources, and surgical staff and in

selected patients with potential for good outcomes.

Echocardiography assists in the management of patients

with cardiogenic shock in several ways: (1) by identifying surgi-

cally correctable valvular abnormalities such as severe aortic or

mitral valvular disease that may be contributing to failure, (2) by

identifying segmental wall motion abnormalities suggestive of

ischemia, and (3) by establishing baseline left ventricular func-

tion in patients with new onset congestive heart failure.

A pulmonary artery catheter will enable the physician to

adjust medications more carefully, with the goal of maximizing

cardiac output at acceptably high end-diastolic filling pressures.

The pulmonary artery catheter is strongly recommended to

help guide the management of congestive heart failure patients

who have hypotension and congestive symptoms. Using a pul-

monary artery catheter, a cardiac index (cardiac output divided

by body surface area) of less than 2 L/min/m

2

is considered car-

diogenic shock and is incompatible with prolonged survival.

Heart rate and cardiac output need to be considered in optimiz-

ing hemodynamics, particularly in patients with congestive

heart failure and myocardial ischemia. If an adequate cardiac

index is maintained by an increased heart rate rather than

improved stroke volume, ultimate outcome will be poor.

Conversely, patients with bradycardia in the setting of conges-

tive heart failure may have dramatically improved cardiac out-

put with a pacemaker or the use of pharmacologic agents that

increase the heart rate.

Calculation of stroke volume to assess therapy is very use-

ful. The mixed venous oxygen (O

2

) saturation (S

–

v

O

2

) is another

way of assessing severity of disease and response to therapy. It

reflects delivery and utilization of O

2

and the effectiveness of

cardiac output. Some pulmonary artery catheters have an

oximeter probe at their tips to continuously monitor S

–

v

O

2

in

addition to pulmonary artery pressures. A decrease in S

–

v

O

2

can

be an early marker of decreased cardiac output and function. A

desirable goal of therapy in treating cardiogenic shock is to

attain a mixed venous O

2

saturation of greater than 70%.

After optimizing hemodynamic variables with intravenous

medications and attaining a period of stability, a gradual change

to oral medication is appropriate. Oral afterload-reducing agents

(eg, ACE inhibitors, angiotensin-receptor blockers, or hydralazine)

should be added while reducing the dosages of intravenous

agents. An intravenous ACE inhibitor such as enalaprilat given

every 6 hours is an alternative to oral ACE inhibitors.

3. Congestive heart failure with severe systemic

hypertension—Treatment is directed at the pathophysio-

logic mechanisms of congestive heart failure in severe hyper-

tension, including reduction of systemic blood pressure and

intravascular volume. In these patients, left ventricular sys-

tolic function may be normal, whereas left ventricular dias-

tolic dysfunction is a major problem resulting in congestion

and pulmonary edema. Systolic dysfunction, if present, may

improve significantly following afterload reduction.

Control of blood pressure with reduction of left ventric-

ular afterload is the major focus of initial therapy. If systolic

function is unknown, an intravenous agent such as nitro-

prusside or nitroglycerin is recommended to lower systemic

pressures and to improve filling pressures acutely. Intravenous

CARDIAC PROBLEMS IN CRITICAL CARE

473

enalaprilat also can be considered (see the section “Hypertensive

Crisis”). For continued treatment of hypertension, β-adrenergic

blockers or calcium channel blockers can be added after conges-

tive heart failure has improved and acceptable left ventricular

systolic function has been documented. However, these agents

should be used with caution in patients with high filling pres-

sures and severe hypertension because they may depress

myocardial function without adequately reducing the afterload.

The net result may be worsening congestive heart failure or

hemodynamic collapse. Pulmonary artery catheterization may

be helpful when considering the use of β-adrenergic blockers or

calcium channel blockers in these patients, but catheterization is

not needed to initiate therapy with nitroprusside unless

hypotension develops early in treatment, raising the possibility

of complicating cardiac or pulmonary problems.

4. High-output or volume-overload congestive heart

failure—These patients present with congestive symptoms

and signs (eg, pulmonary edema and peripheral edema), but

systolic cardiac function is normal, and cardiac output may be

elevated. Treatment should be directed at the cause of the high

cardiac output (eg, anemia, thiamine deficiency, sepsis, and

hyperthyroidism) or volume overload state (eg, renal failure,

iatrogenic volume overload, and excessive sodium intake).

Rapid lowering of intravascular volume by ultrafiltration may

improve blood pressure, hypoxemia, and edema, especially in

patients who do not respond well to diuretic therapy. In the

ICU patient, volume overload may be due to obligate fluid

intake from hyperalimentation, blood product replacement, or

antibiotic therapy.

5. Congestive heart failure with diastolic dysfunc-

tion—Diastolic dysfunction means that ventricular filling is

impaired, and left ventricular end-diastolic pressures may be

elevated. Diastolic dysfunction is the most difficult form of

heart failure to treat. Systolic function is preserved, but ven-

tricular relaxation and filling are inadequate. Diastolic dys-

function is seen commonly in patients who have

hypertension with left ventricular hypertrophy and/or

ischemia. Patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy also

can have significant diastolic heart failure with preserved sys-

tolic function. Elderly patients can have undiagnosed diastolic

heart failure with or without systemic hypertension. Patients

with amyloidosis also have low ventricular compliance

resulting in diastolic dysfunction, but systolic dysfunction

often accompanies this clinical picture. Patients with dias-

tolic dysfunction have congestive symptoms (eg, shortness

of breath and pulmonary edema) despite normal ejection

fraction and normal systolic wall motion. Diuretics usually

are required to reduce preload and symptoms related to

elevated left atrial pressure. Beta-adrenergic blockade to

slow the heart rate, allowing more time for diastolic filling,

can be helpful. On occasion, too aggressive diuretic therapy

becomes counterproductive in patients with diastolic dys-

function by reducing stroke volume, systemic blood pres-

sure, and cardiac output. Because cardiac output is the

product of heart rate and stroke volume, excessive bradycardia

from beta-blockers or calcium channel blockers also can

worsen the clinical situation by causing an inadequate cardiac

output.

6. Isolated right-sided heart failure with pulmonary

hypertension—Patients may have isolated right-sided heart

failure secondary to pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH).

Pulmonary hypertension may be related to congenital heart

disease, lung disease , medications, liver disease (eg, portopul-

monary hypertension), HIV infection, and collagen vascular

diseases (eg, scleroderma and mixed connective tissue disease)

or may be idiopathic. PAH owing to pulmonary emboli or

proximal pulmonary arterial thrombus need to be considered

and excluded with appropriate diagnostic tests before conclud-

ing that pulmonary hypertension is due to a pulmonary arteri-

opathy. Pulmonary venous hypertension also must be excluded

(ie, left-sided heart disease). In PAH, the pathophysiologic

mechanism of the dyspnea and orthopnea is not entirely clear,

although gas exchange in the lungs is inefficient because of

maldistribution of perfusion. Compression of the left ventricle

with abnormal septal motion and relative left ventricular filling

difficulties because of right ventricular encroachment into the

pericardial space is another possible mechanism.

Diuretics are used to reduce right atrial pressure and

right ventricular and right atrial volume. Oxygen may

reduce pulmonary hypertension in patients with PAH or

lung diseases. As oxygenation improves, liver engorgement,

abdominal distention, and lung mechanics improve. One

goal is to reduce right atrial pressure to less than 10 mm Hg.

Finally, digoxin may be helpful by increasing right ventricu-

lar function. Reduction of pulmonary artery pressures and

right ventricular afterload with nitric oxide or intravenous

prostacyclin should be considered when a clear diagnosis of

PAH is made (in the absence of left-sided heart failure). In

the last 3 to 4 years, there have been dramatic advances in the

treatment of PAH in terms of chronic management, includ-

ing the use of endothelin-receptor blockers (eg, bosentan),

phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors (PDE-5) including sildenafil,

and prostacyclins (eg, epoprostenol, treprostinol, and ilo-

prost). Acute treatment with inhaled nitric oxide can restore

oxygenation and stabilize a patient until long-term treat-

ment issues can be addressed. This is in the realm of tertiary

care at institutions able to administer such therapy.

Abraham WT et al: In-hospital mortality in patients with acute

decompensated heart failure requiring intravenous vasoactive

medications: An analysis from the Acute Decompensated Heart

Failure National Registry (ADHERE). J Am Coll Cardiol

2005;46:57–64. [PMID: 15992636]

Bradley TD et al: Continuous positive airway pressure for central

sleep apnea and heart failure. N Engl J Med 2005;353:2025–33.

[PMID: 16282177]

Fonarow GC et al: Characteristics, treatments, and outcomes of

patients with preserved systolic function hospitalized for heart

failure: A report from the OPTIMIZE-HF Registry. J Am Coll

Cardiol 2007;50:768–77. [PMID: 17707182]

Hunt SA et al: ACC/AHA 2005 guideline update for the diagnosis

and management of chronic heart failure in the adult.

Circulation 2005;112:e154–235. [PMID: 16160202]

CHAPTER 21

474

Jessup M et al: Heart failure. N Engl J Med 2003;348:2007–18.

[PMID: 12748317]

Mehra MR: Optimizing outcomes in the patient with acute decompen-

sated heart failure. Am Heart J 2006;151:571–9. [PMID: 16504617]

Onwuanyi C, Taylor M: Acute decompensated heart failure:

Pathophysiology and treatment. Am J Cardiol 2007;99:25–30D.

[PMID: 17378992]

Peter JV et al: Effect of non-invasive positive pressure ventilation

(NIPPV) on mortality in patients with acute cardiogenic pul-

monary edema: A meta-analysis. Lancet 2006;367:1155–63.

[PMID: 16616558]

Publication Committee for the Vasodilatation in the Management

of Acute CHF (VMAC) Investigators: Intravenous nesiritide vs

nitroglycerin for treatment of decompensated congestive heart

failure: A randomized, controlled trial. JAMA 2002;287:

1531–40. [PMID: 11911755]

Yancy CW et al: Clinical presentation, management, and in-hospital

outcomes of patients admitted with acute decompensated heart

failure with preserved systolic function: A report from the Acute

Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry (ADHERE)

Database. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;47:76–84. [PMID: 16386668]

Zile MR, Baicu CF, Gaasch WH: Diastolic heart failure:

Abnormalities in active relaxation and passive stiffness of the left

ventricle. N Engl J Med 2004;350:1953–9. [PMID: 15128895]

Valvular Heart Disease

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Valvular insufficiency:

Dyspnea, pulmonary edema, new murmur.

Echocardiogram with Doppler demonstrating regurgitation.

Valvular stenosis:

Dyspnea, pulmonary edema, murmur, syncope,

hypotension; decreased carotid pulses (aortic stenosis).

Atrial fibrillation (mitral stenosis), left ventricular

hypertrophy (aortic stenosis).

Echocardiogram documenting decreased valve area.

Prosthetic valve dysfunction:

New onset of symptoms of congestive heart failure,

syncope; change in examination (new murmur,

change in intensity of valve sounds).

Echocardiographic evidence of increased valve pres-

sure gradient, thrombosis, or other dysfunction.

Infective endocarditis:

May or may not have history of valvular heart dis-

ease or prosthetic valve.

New onset of heart failure with valvular insufficiency

or unexplained fever and pathologic heart murmur.

Echocardiographic evidence of valvular disease, pos-

itive blood cultures.

General Considerations

As with congestive heart failure, treating valvular heart dis-

ease in the ICU setting involves considering the possibility

and proceeding to assess its severity. Few ICUs can afford the

luxury of a quiet place to auscultate the heart, but with

patience and perseverance, the experienced clinician can

detect important murmurs. The acoustic qualities of the

murmurs are affected by cardiac output. Patients in shock

with low-output states and febrile or anemic patients with

high-output states may present with misleading physical

findings that under- or overestimate the severity of their

valvular heart disease. At the bedside, echocardiography

affords the physician a convenient window on the heart and

a way to quantitate valve dysfunction and clarify the relation-

ship between valve function and myocardial function.

Acute valvular insufficiency with regurgitation may be

due to endocarditis, trauma, papillary muscle dysfunction

(mitral valve), or ischemia. Patients may present with wors-

ening of chronic valvular disease from myxomatous degener-

ation or prolapse with and without connective tissue

disorders or rheumatic heart disease. Isolated aortic valve

insufficiency may be due to aortic diseases such as aortic dis-

section, cystic medial necrosis, and syphilitic aortitis. Most

commonly, however, chronic aortic regurgitation results

from a congenital bicuspid aortic valve. Mitral stenosis is

almost always due to rheumatic heart disease. Aortic stenosis

is occasionally due to rheumatic heart disease but more often

is due to progressive valvular calcification in the elderly,

either of a normal valve or of a congenital bicuspid valve.

Patients with previous valve surgery with prosthetic or

bioprosthetic valves represent a special circumstance. These

valves are subject to a variety of chronic and acute complica-

tions, including infective endocarditis, calcification with

simultaneous stenosis and incompetence, thrombosis with

valve dysfunction, and peripheral embolic events such as

strokes, valve dehiscence, and paravalvular leaks. Valve

repairs also can be subject to some of the same problems,

including endocarditis, recurrent valve dysfunction, and rel-

ative valve stenosis, after repair of valvular regurgitation.

Clinical Features

A. Symptoms and Signs—Specific findings depend on

which valve is abnormal. Patients with aortic or mitral valvu-

lar stenosis or insufficiency may present with congestive heart

failure, including pulmonary edema and evidence of

decreased cardiac output. Physical findings include rales, S

3

gallop, wheezing, peripheral vasoconstriction, tachycardia,

and murmurs. Other important findings to be sought include

the character of arterial pulses, intensity of the heart sounds,

and changes in the quality of murmurs with different maneu-

vers such as the Valsalva maneuver. Chest pain is a frequent

accompanying symptom in patients with significant aortic

stenosis or aortic regurgitation. Atrial arrhythmias frequently

accompany mitral valve disease with left atrial enlargement.

CARDIAC PROBLEMS IN CRITICAL CARE

475

B. Electrocardiography—The ECG may suggest features of

specific valvular as heart diseases—for example, left ventric-

ular hypertrophy as seen in aortic stenosis and regurgitation,

and left atrial enlargement and right ventricular hypertrophy

as seen in mitral stenosis.

C. Imaging Studies—The chest x-ray may show cardiomegaly

with specific chamber enlargement. Echocardiography is

extremely useful in assessing valvular heart disease. It can

provide evidence of leaflet abnormalities, including vegeta-

tions and decreased motion of valve leaflets, as well as esti-

mates of valve cross-sectional area in valvular stenosis. The

size of the atria and ventricles can be determined and wall

motion and ejection fraction estimated. With Doppler tech-

niques, one can quantitatively estimate regurgitant blood

flow across an abnormal valve, measure valve pressure gradi-

ents and calculate valve areas.

D. Additional Studies—Pulmonary artery catheters directly

measure pulmonary artery pressures and cardiac output and

provide an estimate of left atrial pressure (pulmonary artery

wedge pressure). Cardiac catheterization is usually required

to assess valve function prior to surgery and to identify coex-

istent coronary artery disease.

Treatment: Native Valves

A. Valvular Regurgitation—The management of left-sided

valvular regurgitation is determined by the severity of the

regurgitation, the specific cause, and the degree of left ven-

tricular dysfunction. The severity of regurgitation can be

estimated echocardiographically using color-flow and

continuous-wave Doppler and calculating left ventricular

and left atrial pressures noninvasively. Echocardiography

also will help to define operability and determine the cause

of the valve dysfunction. Mild to moderate aortic or mitral

regurgitation without symptoms requires no treatment. In

patients with more severe left-sided valvular regurgitation,

associated congestive heart failure (pulmonary edema) can

be treated with diuretics and digoxin. However, the most

important therapy is the use of unloading agents such as

ACE inhibitors, hydralazine, and, if needed, nitroglycerin

and nitroprusside. These drugs work by decreasing down-

stream resistance and increasing downstream compliance.

Forward blood flow increases while regurgitant flow

decreases, so ventricular filling pressures decline while car-

diac output improves. The management of congestive heart

failure owing to aortic or mitral regurgitation is quite similar

to the management of congestive heart failure owing to sys-

tolic ventricular dysfunction.

In patients with such severe valvular regurgitation that

cardiac output is very low and there is hypotension (cardio-

genic shock), emergent valve surgery may be necessary.

Invasive hemodynamic monitoring with a pulmonary artery

catheter is essential, and maximal unloading of the left ventri-

cle with intravenous nitroprusside should be started immedi-

ately. Inotropic drugs such as dopamine may be required to

maintain adequate systemic blood pressure even though—by

increasing afterload—valvular regurgitation may be tran-

siently worsened. Mitral regurgitation associated with car-

diogenic shock may benefit from an intraaortic balloon

pump, but this therapy is contraindicated in those with aor-

tic valve regurgitation.

B. Valvular Stenosis—Aortic stenosis is treated with sur-

gery when it results in congestive heart failure. Choices for

medical management are limited, but possible pharmaco-

logic interventions include mild diuresis and the use of

digoxin. Systemic vasodilators, useful in other forms of heart

failure, may cause severe hypotension in patients with aortic

stenosis. In selected patients with combined stenosis and

ventricular dysfunction, judiciously used intravenous

unloading therapy has been employed with hemodynamic

monitoring. This type of hemodynamic manipulation is per-

formed in the catheterization laboratory or under the guid-

ance of a cardiologist and is not the standard of care.

Dopamine can be tried if shock develops, but by this time,

surgery is essential. A rapid and limited search for confound-

ing problems can be undertaken to try to find ways to

improve the patient acutely. Atrial fibrillation, for example,

because it results in a decrease in left ventricular filling in the

patient with severe aortic stenosis, should be treated aggres-

sively with the goal of returning the patient to sinus rhythm.

Successful cardioversion of atrial fibrillation may result in

acute improvement in cardiac output.

Severe mitral stenosis is also a surgical problem, although

it is somewhat more amenable to pharmacologic therapy. The

most important goal is to decrease the heart rate, thereby pro-

longing diastolic filling time and allowing the left atrium to

empty. Left atrial pressure and, therefore, pulmonary venous

pressure are determined by the degree of left atrial emptying.

In patients with mitral stenosis, left atrial emptying is limited

by decreased mitral orifice size, and the smaller the valve area,

the longer it takes for the atrium to empty. Inadequate time

for emptying leads to increased left atrial pressure and vol-

ume and worsening pulmonary congestion. Thus, by slowing

the heart rate and lengthening diastole, the left atrium has

more time in which to empty. Therefore, if left ventricular

function is preserved and there is only mild to moderate

mitral regurgitation, heart rate control using beta-blockers or

calcium channel blockers (or digoxin, if the patient has atrial

fibrillation) often will greatly improve symptoms.

Treatment: Prosthetic Valves

A. Transvalvular Dysfunction of Prosthetic Valves—This

entity can be a true medical emergency resulting in rapid

deterioration of a stable patient and can lead to death if not

recognized and treated promptly. Bioprosthetic valves tend

to calcify and become both stenotic and incompetent over

time. Once the valve becomes dysfunctional, further progres-

sion can be rapid, with a rigid leaflet suddenly becoming

severely incompetent and producing fulminant congestive

CHAPTER 21

476

heart failure. Mechanical prosthetic valves are more durable,

with, for example, Starr-Edwards valves (ball-cage valves)

functioning for more than 30 years. However, ingrowth of

tissue (pannus formation) or thrombosis secondary to inad-

equate anticoagulation can result in the development of valve

dysfunction with either obstruction, regurgitation, or both

depending on where the tissue ingrowth or clot develops.

Progressive thrombosis, particularly on a single-leaflet

mechanical valve, can result in death because the valve may

stick in the closed position. The St. Jude valve, because it is a

bileaflet device, usually develops both insufficiency and

stenosis. Other less frequent problems have resulted from

mechanical damage to the valve, such as strut fracture with

Björk-Shiley-type valves and loss of poppets owing to ball

variance and fractures in the older Starr-Edwards valves. In

evaluating patients with suspected prosthetic valve dysfunc-

tion, physical examination may show evidence of congestive

heart failure. The murmurs that accompany the prosthetic

valve may be fainter than usual because of low cardiac out-

put or high filling pressures. The key to the diagnosis of pros-

thetic valve dysfunction is a high degree of clinical suspicion

and noninvasive assessment of valvular function. Patients

with prosthetic valves who present with worsening heart fail-

ure should undergo Doppler evaluation of the valves to

assess gradients across the valves and to estimate valve area.

Transesophageal echocardiography is extremely useful in this

setting and can confirm valve obstruction by demonstrating

the presence of a clot and reduced prosthetic leaflet motion.

A large pressure gradient across the valve or the presence of

substantial transvalvular regurgitation is suggestive of valve

thrombosis. Cinefluoroscopy can be used to assess opening

angles of the mechanical prosthetic valves by measuring the

angle on still frames. The angle of opening for specific valve

models is known. If the valve does not open to the expected

amount, valve dysfunction and thrombosis can be suspected.

Treatment includes immediate heparinization if throm-

bosis is suspected, hemodynamic monitoring, and surgical

evaluation for urgent valve replacement. Valve replacement is

critical and can be lifesaving. Patients who present with

severe heart failure in this setting sometimes can be helped

dramatically by use of thrombolytic agents, including

alteplase or streptokinase. Risks of thrombolytic therapy

include embolization of lysed clots and CNS hemorrhage,

but the risks may have to be accepted when cardiogenic

shock occurs secondary to valve thrombosis and surgery is

considered too hazardous. Results with alteplase can be seen

within 90 minutes. Heparinization must be continued after

thrombolytic therapy to prevent immediate thrombosis.

B. Emboli—Thrombi forming on prosthetic valves are a

source of thromboemboli, which can cause complications

based on where the emboli lodge, including strokes, renal

infarction, ischemic limbs, pulmonary emboli, and coronary

artery occlusion. Emboli occur uncommonly in anticoagu-

lated patients; however, inadequate anticoagulation or discon-

tinuation of anticoagulation—particularly with mechanical

valves—can result in embolic events. Treatment is supportive

with use of intravenous anticoagulation for treatment of

peripheral embolization and prevention of further emboli.

Surgical removal of emboli can be performed if they are in

accessible locations, such as in limb vessels. In patients who are

already adequately anticoagulated with warfarin, the addition

of aspirin or dipyridamole has been shown to decrease the fre-

quency of recurrent embolization.

In patients with cerebral emboli, the decision to anticoag-

ulate may be difficult because of the risk of conversion of a

bland embolic stroke to a hemorrhagic one. Most neurolo-

gists recommend waiting 48–72 hours before anticoagulating

such patients unless the concern for recurrent emboli is felt

to outweigh these risks. Finally, surgical replacement of a

partially thrombosed valve in a patient with stroke is associ-

ated with a very high risk of perioperative intracerebral hem-

orrhage owing the combination of low cerebral perfusion

and the need for heparin during the procedure.

C. Paravalvular Leaks and Valve Dehiscence—Valve dehis-

cence is another form of valve dysfunction seen with both bio-

prosthetic and mechanical valves. The artificial valve is attached

to the myocardium or to the annulus where the native valve

previously resided. Paravalvular leaks can be a result of techni-

cal problems occurring at the time of surgery or may develop

years later as a result of prosthesis infection (endocarditis).

Paravalvular leaks are a result of space developing between the

sewing ring of the valve and the annulus or cardiac tissue.

Small, hemodynamically insignificant leaks are often seen as a

result of minor surgical imperfections and can remain stable

for years. Paravalvular leaks secondary to infective endocarditis

often are associated with valve dehiscence, and these paravalvu-

lar leaks tend to progress—often rapidly. This results in severe

hemodynamic dysfunction, further dehiscence of the valve,

instability of the valve, and frequently, hemolysis owing to

mechanical destruction of red blood cells as they pass through

the disordered valve. However, paravalvular leaks can develop

over time even in the absence of infection.

Development of a paravalvular leak in the setting of

endocarditis is a surgical emergency. Complications include

progressive uncontrollable congestive heart failure, sepsis,

and complete dehiscence of the valve resulting in death.

Echocardiography—particularly transesophageal—or car-

diac catheterization is required to define the severity of the

valve lesions, assess overall cardiac function, and guide valve

replacement. In the absence of infection, the decision with

regard to valve replacement is determined by the degree of

regurgitation and associated heart failure. Paravalvular leaks

that increase over time suggest instability of the valve and

necessitate valve replacement.

Treatment: Infective Endocarditis (Prosthetic

or Native Valve)

Infective endocarditis is a pleomorphic disease that can be

rapidly progressive when caused by invasive organisms or

can be slowly progressive and debilitating resulting in