Bongard Frederic , Darryl Sue. Diagnosis and Treatment Critical Care

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

CRITICAL CARE OF THE ONCOLOGY PATIENT

457

METABOLIC DISORDERS

Hypercalcemia of Malignancy

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Mental status changes, lethargy, confusion, weakness.

Altered deep tendon reflexes without localized neuro-

logic signs.

History of malignancy, usually far-advanced.

Elevated serum calcium, chloride:phosphate ratio, and

(often) parathyroid hormone–related polypeptide

(PTHrP).

General Considerations

Hypercalcemia is the most serious metabolic disorder associ-

ated with cancer. Between 10% and 20% of patients with can-

cer will develop hypercalcemia at some point, and life

expectancy is poor in these patients, even when they are

actively treated. Treatment of hypercalcemia of malignancy is

usually palliative because most of these patients have

advanced disease. However, symptoms are usually improved

with treatment, and many patients may be made well enough

to go home from the hospital. While treatment of hypercal-

cemia may not prolong survival, it clearly improves quality

of life.

Pathogenesis

Serum calcium is regulated by hormones and locally acting

cytokines at three main sites: the gut, the skeletal system, and

the kidneys. Parathyroid hormone (PTH) increases the num-

ber and function of osteoclasts, inhibits osteoblasts, and

increases renal tubular reabsorption of calcium, all of which

increase extracellular calcium levels. The hormone also

increases production of active vitamin D, which increases the

absorption of calcium from the gut.

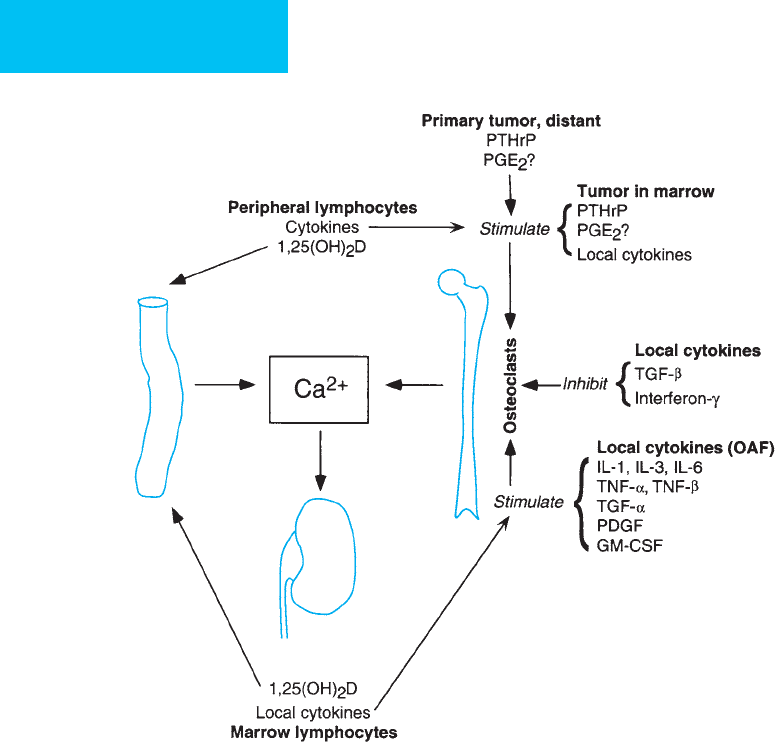

In all cases of cancer-related hypercalcemia, there is

increased calcium resorption from bones relative to bone

formation (Figure 20–1). Increased bone resorption is

maintained through the destructive action of tumor cells by

increased osteoclast activation mediated through the action

of PTH-related polypeptide (PTHrP) and by locally acting

cytokines. Squamous cell carcinomas originating in the

lung, head and neck, esophagus, uterine cervix, vagina, and

penis—as well as cancers of the breast, lung, and kidney—

produce PTHrP. This hormone shares homology with the

amino-terminal portion of parathyroid-produced PTH

only in 8 of the first 13 amino acids. It has predicted iso-

forms of 139, 141, and 173 amino acids compared with 84

amino acids in PTH. PTHrP, like PTH, can mediate bone

resorption of calcium and renal tubular absorption of

calcium, but unlike PTH, serum calcium levels do not regu-

late its secretion. Recently, an aberrant extracellular calcium-

sensing receptor (CaR) has been associated with a

counterproductive increased release of PTHrP by tumor

cells, as well as potentially stimulating cell growth and

inhibiting apoptosis.

PTH and PTHrP are distinguishable by radioassay, and

for this reason, it is possible to distinguish humoral hypercal-

cemia of malignancy from coexisting primary hyperparathy-

roidism. Despite a high frequency of bony metastases,

prostate, small cell lung cancer, and colorectal carcinoma are

rarely associated with hypercalcemia.

In addition to PTHrP, a number of locally active

cytokines augment resorption of calcium from bone, includ-

ing interleukin 1 (IL-1), IL-3, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-11 and

tumor necrosis factors (TNF-α and TNF-β)—all of which

are components of what was formerly called osteoclast-

activating factor. Furthermore, transforming growth factor

(TGF-α), platelet-derived growth factor, and certain

hematopoietic colony-stimulating factors such as granulocyte-

macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) also can

augment bone resorption. In patients with myeloma,

increased bone resorption from cytokines is the primary

mechanism of hypercalcemia. Prostaglandin E

2

also can

increase bone resorption. Two locally acting cytokines also

decrease the amount of calcium from bone: interferon-γ

and transforming growth factor β (TGF-β). Both inhibit

osteoclasts and bone resorption, and TGF-β promotes

osteoblast activity.

Some Hodgkin’s and non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas can 1-

hydroxylate sufficient amount of vitamin D to its more

highly active form. This increases gut absorption of calcium

and, together with the calcium resorption from cytokines

acting locally in bone, may produce hypercalcemia.

Hypercalcemia is a prominent feature of adult T-cell lym-

phomas (45% of cases) and of lymphomas and leukemias

associated with HTLV-1 (90%).

Clinical Features

When hypercalcemia results from malignancy, the cancer is

rarely occult. Patients with severe hypercalcemia (serum cal-

cium >14 mg/dL) are usually symptomatic. These symptoms

are often related to the rapidity of onset of hypercalcemia.

The clinical features of hypercalcemia and, in particular,

its neuromuscular manifestations tend to be much more

prominent in the elderly. Other factors such as the patient’s

performance status, recent chemotherapy, sites of metastasis,

and the presence of hepatic or renal dysfunction may

increase the severity of symptoms. Since calcium is a critical

regulator of cellular function, patients with hypercalcemia

may have a wide range of symptoms affecting different organ

systems. Conversely, the most common symptoms of hyper-

calcemia may be nonspecific and are similar to those seen in

patients with chronic or terminal illnesses, such as nausea,

anorexia, weakness, fatigue, lethargy, and confusion. In late

CHAPTER 20

458

stages, patients may be stuporous or comatose, and their

symptoms may mimic a neurologic emergency.

A. Neurologic—The major neurologic manifestations

include weakness, altered mental status, and altered deep

tendon reflexes. Initial manifestations may include subtle

personality changes, impaired concentration, apathy, mild

confusion and irritability, lethargy, hallucinations, and psy-

chosis, with progression to stupor and coma. Focal neuro-

logic signs are usually absent.

B. Gastrointestinal—Because of the depressive action of

hypercalcemia on autonomic nervous tissue, nonspecific

symptoms such as anorexia, nausea, and vomiting may

occur. These often progress to include abdominal pain, con-

stipation, frank obstipation, increased gastric acid secretion,

and acute pancreatitis.

C. Renal—Hypercalcemia causes a reversible tubular defect

in the kidney that limits urinary concentrating ability and

promotes dehydration or hypovolemia. If able, patients will

admit to polyuria, nocturia, and polydipsia. Metabolic alka-

losis is common, and acidosis occurs only when azotemia

supervenes. This contrasts with the effects of PTH, in which

a mild hyperchloremic acidosis is seen. Hypercalcemia also

can lead to precipitation of calcium phosphate crystals in the

Figure 20–1. Mechanisms of hypercalcemia of malignancy. Osteoclast activity can be stimulated by hormones,

cytokines, and other substances from certain primary tumors distant from bone or by tumor in the bone marrow. In

other patients, local production of cytokines known as osteoclast-activating factors are the primary mediators of

increased calcium mobilization. Both peripheral blood and marrow lymphocytes produce cytokines that affect osteo-

clasts. 1,25(OH)

2

vitamin D increases calcium absorption from the small intestine. Other local cytokines have an

inhibitory effect on osteoclast activity. [1,25(OH)

2

D = vitamin D; PTHrP = parathyroid hormone–related polypeptide;

IL = interleukin; TGF-α and TGF-β = transforming growth factors α and β; TNF-α and TNF-β = tumor necrosis factors α

and β; PDGF = platelet-derived growth factor; GM-CSF = granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor.]

CRITICAL CARE OF THE ONCOLOGY PATIENT

459

kidneys and ureters and the formation of renal calculi. Such

complications, however, are not commonly associated with

hypercalcemia of malignancy, and when they occur, the pos-

sibility of coexisting primary hyperparathyroidism should be

considered.

D. Cardiovascular—Hypercalcemia may cause electrocar-

diographic disturbances such as prolongation of the PR and

QRS intervals and shortening of the QT interval. With severe

hypercalcemia (>16 mg/dL), the T wave widens, increasing

the QT interval. At higher serum calcium concentra-

tions, bradyarrhythmias and bundle branch block may

develop, followed by complete heart block and cardiac arrest

in systole.

E. Bone and Extraskeletal Tissues—Hypercalcemia can

result either from humorally mediated bone resorption or

from osteolytic metastasis. Pain, fractures, and skeletal defor-

mities can occur. Metastatic calcification occurs in long-

standing and very severe hypercalcemia. Extraskeletal

deposition of calcium has been observed with hypercalcemia

in several organs, including the heart, lungs, kidneys, skin,

joints, and conjunctivae.

F. Laboratory Findings—Serum calcium, phosphate, and

albumin levels should be determined in all patients. Ionized

calcium is responsible for clinical manifestations and is

almost half the total serum calcium in normal subjects (the

rest is protein-bound). Measured ionized calcium is the

most accurate predictor of clinical features. A clinical esti-

mate of the “effect” of ionized calcium is the corrected

serum calcium equal to the measured calcium + 0.8 ×

(4 – measured albumin). This calculation is especially

helpful when hypoalbuminemia coexists with hypercal-

cemia. Hypophosphatemia in the presence of hypercal-

cemia strongly suggests the presence of PTHrP or primary

hyperparathyroidism. Elevated alkaline phosphatase is usu-

ally not helpful because it is seen in both primary hyper-

parathyroidism and hypercalcemia of malignancy. Direct

measurement of PTH and PTHrP may be necessary in some

patients.

G. Radiographs—Nephrocalcinosis and nephrolithiasis may

be present in long-standing hypercalcemia and suggest

hyperparathyroidism.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of hypercalcemia of malignancy

includes a wide variety of conditions (Table 20–2). Among

all patients, the two most common causes of hypercalcemia

are malignancy (35%) and primary hyperparathyroidism

(54%). Among hospitalized patients with hypercal-

cemia, 77% have malignancies, 4% have coexistent hyper-

parathyroidism, 2% have vitamin D intoxication, 2%

have tamoxifen-induced hypercalcemia, and 16% are due to

other causes. Table 20–3 lists features that may be used to

differentiate primary hyperparathyroidism from hypercal-

cemia of malignancy.

Treatment

There is no one regimen that should be applied to the acute

management of all cases of hypercalcemia. Moderate hyper-

calcemia with minimal symptoms may be managed with

administration of intravenous 0.9% NaCl. If the hypercal-

cemia is more severe and is symptomatic, furosemide and

calcitonin may be added. Since the effects of calcitonin are

not long-lasting, the use of bisphosphonates early in treat-

ment is indicated. In patients with lymphoma or myeloma

and hypercalcemia, corticosteroids are useful because of the

significant role of cytokines in the hypercalcemia.

Intravenous administration of sodium phosphate can lower

the serum calcium level rapidly, but its use is dangerous

because calcium phosphate complexes will deposit in blood

vessels, lungs, and kidneys with resulting severe organ dam-

age and even fatal hypotension. Therefore, intravenous phos-

phates are not recommended. Oral phosphates are of limited

value because diarrhea often develops with an intake of more

than 2 g/day. Azotemia and hyperphosphatemia are con-

traindications to phosphate therapy.

Table 20–2. Causes of hypercalcemia.

I. Primary hyperparathyroidism (54%)

II. Cancer (35%)

A. Caused by hormones (HHM) (80%)

1. Most common: Lung cancer (especially epidermoid) and renal

cell carcinoma.

2. Less common: Head and neck cancer, ovarian cancer,

hepatoma, pancreatic cancer, bladder cancer, endometrial

cancer, lymphomas, leukemia, multiple myeloma.

3. Isolated case reports: Esophageal cancer, colon cancer, rectal

cancer, cervical cancer, uterine leiomyosarcoma, vulvar cancer,

cancer of the penis, prostate cancer, adrenal cancer, melanoma,

hemangiopericytoma, branchial rest cancer, parotid cancer,

breast cancer, mammary dysplasia.

B. Caused by metastatic destruction of bone (20%). Breast cancer

(most common), multiple myeloma, lymphoma, and leukemia.

III. Others (11%)

A. Nonparathyroid endocrine disorders: Thyrotoxicosis, pheochromo-

cytoma, adrenal insufficiency, vasoactive intestinal polypeptide

hormone-producing tumor.

B. Granulomatous diseases: 1,25-(OH)

2

vitamin D excess, sarcoidosis,

tuberculosis, histoplasmosis, coccidioidomycosis, leprosy.

C. Medications: Thiazide diuretics, lithium, estrogens, and antiestrogens.

D. Milk-alkali syndrome.

E. Vitamin A or vitamin D intoxication.

F. Familial hypocalciuric hypercalcemia.

G. Immobilization.

H. Parenteral nutrition.

HHM = humoral hyperglycemia of malignancy.

CHAPTER 20

460

Therapy for hypercalcemia in cancer patients centers on

four main mechanisms: (1) correction of volume depletion,

(2) inhibition of bone resorption of calcium, (3) enhance-

ment of renal calcium excretion, and (4) treatment of the

underlying malignancy. Table 20–4 summarizes the available

drugs and their dosages.

A. Fluid and Electrolytes—Volume and electrolyte reple-

tion are the first priorities. Normal saline (0.9% NaCl), usu-

ally containing potassium chloride (10–20 meq/L), is given at

a rate of 2–3 L/day. Loop diuretics such as furosemide (40–80 mg

intravenously) are used to induce calciuresis and preclude

volume overload once fluid deficits are corrected. Judicious

fluid administration or central venous pressure monitoring

may be appropriate in patients with poor urine output or

congestive heart failure. As a result of calcium-related renal

tubular impairment and the resulting polyuria, urine out-

put may not be a reliable measure of intravascular volume

repletion.

B. Calcitonin—Calcitonin is a useful adjunct in the initial

phase of therapy. It is nontoxic and acts within 4–24 hours.

Calcitonin promotes renal excretion of calcium, inhibits

bone resorption, and inhibits gut absorption of calcium. The

effects of calcitonin, however, are minor and of short dura-

tion. Calcitonin is usually administered over 24 hours as an

intravenous infusion in a dose of 3 units/kg or 100–400 units

subcutaneously every 8–12 hours.

C. Corticosteroids—Corticosteroids decrease intestinal cal-

cium absorption and inhibit bone resorption and in that way

act as vitamin D antagonists. They also inhibit the action of

some of the locally acting cytokines that mediate calcium

mobilization from bone. They are effective primarily in

hematologic malignancies and breast cancer, essentially to

control chronic hypercalcemia.

Primary Hyperparathroidism Hypercalcemia of Malignancy

Symptoms Mild or absent Symptomatic

Serum calcium Mildly increased (<14 mg/dL) Significantly increased (>14 mg/dL)

Serum phosphorus Decreased Variable

Serum potassium Normal Usually decreased

Serum chloride Increased

∗

Low or normal

Serum bicarbonate Decreased (hyperchloremic acidosis) Normal or increased

Urinary calcium Increased Markedly increased

Urinary cAMP Increased Variable

1,25-(OH)

2

vitamin D Increased Usually decreased

∗

Serum chloride:phosphate ratio is increased.

Table 20–3. Features used to differentiate primary hyperparathyroidism from malignancy-

related hypercalcemia.

Table 20–4. Treatment of hypercalcemia of malignancy.

1. IV fluid replacement with 3–6 L of 0.9% NaCl with 40–80 mg of

potassium chloride per liter over 24 hours.

2. Furosemide, 40–160 mg IV over 24 hours.

3. Bisphosphonates:

Pamidronate, 60–90 mg in 1 L 0.9% NaCl over 4–24 hours.

Etidronate, 7.5 mg/kg in 300 mL 0.9% NaCl over 3 hours for

3–5 days.

4. Calcitonin: Extremely useful in patients with life-threatening

hypercalcemia. It has the most rapid action: 2–4 hours.

600 IU in 1 L 0.9% NaCl over 6 hours.

6–8 IU/kg IM every 6–8 hours for 2–3 days.

5. Corticosteroids: 200–300 mg of hydrocortisone per day or equivalent.

6. Gallium nitrate: 200 mg/m

2

in 1 L 5% dextrose over 24 hours for

5 days.

7. Plicamycin: 25 μg/kg for total dose of 1.5–2 mg IV administered

in brief infusion or over 12 hours. No benefit from prolonged

infusion.

8. Phosphates: Oral phosphates, 0.5–3 g/d diluted in water.

IV phosphates should not be given.

Formula to correct serum calcium for changes in serum albumin

concentration: Corrected serum calcium = measured total calcium

value (mg/dL) − serum albumin valve (g/dL) + 4.

CRITICAL CARE OF THE ONCOLOGY PATIENT

461

D. Bisphosphonates—Bisphosphonates are used routinely

because of their efficacy and low toxicity. They are potent

inhibitors of osteoclasts and bind to hydroxyapatite in bone

to inhibit dissolution. A single dose of pamidronate (60–90 mg

in 1 L of normal saline over 4–24 hours) by intravenous infu-

sion is safe and effective. Significant reductions in serum cal-

cium usually occur in 1–2 days and persist for several weeks.

Zoledronic acid is a more potent bisphosphonate that has

been associated with a higher proportion of correction of

hypercalcemia and more rapid normalization than

pamidronate. It is given intravenously as 4 mg over not less

than 15 minutes. The dose must be adjusted for renal insuffi-

ciency. Rare complications of bisphosphonates include acute

systemic inflammatory reaction, eye inflammation, renal fail-

ure, nephrotic syndrome, and hypocalcemia. Jaw osteonecro-

sis is seen primarily with long term use of bisphosphonates.

E. Dialysis—Hemodialysis is very effective in the treatment

of hypercalcemia but is usually reserved for management in

the setting of renal failure or life-threatening manifestations.

F. Other Therapies—Plicamycin and gallium nitrate decrease

bone resorption. Prostaglandin synthetase inhibitors and

other investigational drugs such as amifostine (WR-2721)

have been used. Amifostine inhibits PTH secretion and bone

resorption and facilitates urinary excretion of calcium.

All patients should be encouraged to avoid immobilization

and ambulate. In addition, liberal fluid intake and avoidance

of large amounts of foods rich in calcium are also suggested.

Halfdanarson TR, Hogan WJ, Moynihan TJ: Oncologic emergen-

cies: Diagnosis and treatment. Mayo Clin Proc 2006;81:835–48.

[PMID: 16770986]

Horwitz MJ, Stewart AF: Humoral hypercalcemia of malignancy.

In Favus MJ (ed), Primer on the Metabolic Bone Diseases and

Disorders of Mineral Metabolism, 5th ed. Philadelphia:

Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2003, pp. 246–50.

Spinazze S, Schrijvers D: Metabolic emergencies. Crit Rev Oncol

Hematol 2006;58:79–89. [PMID: 16337807]

Hypocalcemia in Malignant Disease

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Tetany; paresthesias of the face, hands, and feet.

Positive Chvostek and Trousseau signs.

Muscle cramps, laryngeal spasm, headache, lethargy.

Low serum calcium (corrected) or low ionized calcium.

Osteoblastic metastases (breast or prostate cancer) or

tumor lysis syndrome with elevated serum phosphorus.

General Considerations

Hypocalcemia is a rare complication of cancer resulting from

osteoblastic metastasis secondary either to rapid bone healing

in patients with prostate or breast cancer receiving hormonal

therapy or to hyperphosphatemia in patients with tumor

lysis syndrome. The most common neoplasm associated with

hypocalcemia is prostate cancer, and 31% of patients with

prostate cancer and extensive osteoblastic bone metastasis

develop hypocalcemia. The skeleton in these patients has

been described as a “calcium sink.” Hypocalcemia secondary

to tumor lysis syndrome may be severe and appears to

result from a rise in the serum calcium × phosphorus prod-

uct, leading to precipitation of calcium in soft tissues,

including the kidneys, and the development of secondary

hyperparathyroidism.

Hypocalcemia also may occur secondarily in patients with

low circulating 1,25(OH)

2

vitamin D and calcifying chon-

drosarcoma. Magnesium deficiency results in hypocalcemia

in patients with prolonged nasogastric drainage, parenteral

hyperalimentation without magnesium supplementation,

cisplatin therapy, long-term diuretic therapy, chronic diar-

rhea, and chronic alcoholism and does not respond to cal-

cium replacement alone. Treatment of hypercalcemia with

plicamycin, bisphosphonates, or intravenous phosphate also

may cause hypocalcemia.

Clinical Features

The diagnosis of hypocalcemia is made with ease in patients

who develop tetany. Paresthesias of the face, hands, and feet

associated with muscle cramps, laryngeal spasm, diarrhea,

headache, lethargy, irritability, or seizures are the common

clinical manifestations. Chvostek’s and Trousseau’s signs are

usually present. The ECG usually shows a prolonged QT

interval. In long-standing cases, dry skin, papilledema, and

cataracts may develop.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of hypocalcemia should include

severe alkalosis secondary to vomiting, nasogastric suction,

or hyperventilation and severe muscle cramps resulting from

vincristine or procarbazine therapy.

Treatment

Treatment of acute severe hypocalcemia (serum calcium < 6

mg/dL) consists of intravenous administration of calcium

gluconate or calcium chloride, 1 g every 15–20 minutes until

tetany disappears, and magnesium sulfate, 1 g intravenously

or intramuscularly every 8–12 hours if the serum magne-

sium level is less than 1.5 mg/dL or is unknown. In patients

with moderate hypocalcemia (serum calcium >7 mg/dL),

calcium and magnesium may be replaced more slowly.

Carmeliet G et al: Disorders of calcium homeostasis. Best Pract Res

Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003;17:529–46. [PMID: 14687587]

Maalouf NM et al: Bisphosphonate-induced hypocalcemia: Report

of 3 cases and review of literature. Endocr Pract 2006;12:48–53.

[PMID: 16524863]

CHAPTER 20

462

Tumor Lysis Syndrome

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Lethargy, tetany, muscle cramps, convulsions.

Administration of chemotherapy to patient with rapidly

proliferating malignancy.

Elevated serum uric acid, potassium, phosphate, and

urea nitrogen.

General Considerations

When given to a patient with a highly responsive (usually

rapidly growing) malignancy, chemotherapy may trigger

release of massive amounts of potassium, phosphate, uric

acid, and other breakdown products of dying tumor cells

into the bloodstream. Hypocalcemia owing to hyperphos-

phatemia may occur. This syndrome of tumor lysis occurs

most commonly in patients with rapidly proliferating and

chemotherapy-sensitive malignancies, such as acute

leukemia and Burkitt’s lymphoma and, on rare occasions,

following treatment of solid tumors and chronic lympho-

cytic leukemia (CLL). Tumor lysis syndrome has been

reported after chemotherapy, radiotherapy, monoclonal

antibody treatment, corticosteroids, and rarely sponta-

neously. Life-threatening complications may occur, including

renal failure from hyperuricemia and cardiac arrhythmias

induced by hyperkalemia or hypocalcemia.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of tumor lysis syndrome is made most often from

laboratory studies. However, lethargy, tetany, muscle cramps,

and convulsions occurring in a patient with an appropriate

tumor who has just received chemotherapy should prompt

evaluation. Hyperkalemia, hyperphosphatemia, azotemia,

and oliguria usually are present.

Treatment

Early recognition of risk is the key to prevention and treat-

ment of this complication of cancer therapy. Despite appro-

priate treatment, renal insufficiency still may occur.

However, prognosis is good, and recovery to baseline renal

function is expected.

A. Hyperkalemia—Immediate treatment of hyperkalemia

consists of administration of 50–100 mL of 50% dextrose in

water and 10 units of regular insulin. Removal of potassium

can be achieved with oral sodium polystyrene sulfonate,

20–30 g every 6 hours. Hemodialysis may be necessary for

the management of refractory hyperkalemia.

B. Hyperphosphatemia—Hyperphosphatemia is typically

severe, with serum levels ranging from 6 up to as much as

35 mg/dL resulting from tumor cell lysis and subsequent

renal failure. Patients should be given 20% dextrose in water

and insulin until the serum phosphate level falls below 7

mg/dL. Aluminum hydroxide, 30–60 mL orally every 2–6

hours, is used to bind phosphate in the intestines. Oral fluids

are given at the rate of 2–4 L every 24 hours. Dialysis may be

necessary for patients with renal failure. Hyperphosphatemia

may be accompanied by hypocalcemia as well.

C. Hyperuricemia and Hyperuricosuria—Increased uri-

nary uric acid excretion may occur in untreated patients with

rapidly growing malignancies or during their treatment with

chemotherapy or radiation therapy. Uric acid nephropathy

secondary to the precipitation of uric acid crystals in the kid-

neys may result. Nephrolithiasis with urate stones or urate

interstitial nephritis also may occur. When massive doses of

allopurinol are used to prevent uric acid production, renal

oxypurinol stones may form occasionally.

Prevention of anticipated hyperuricemia is the corner-

stone of management. Allopurinol should be given to

patients with myeloproliferative disorders and hematologic

malignancies at least 12 hours before starting chemotherapy.

Rasburicase, a recombinant urate oxidase, does not cause

xanthine and hypoxanthine to accumulate but rather con-

verts urate to allantoin, a much more soluble product.

Rasburicase is much more effective and rapid in lowering

plasma uric acid levels. However, rasburicase is highly

immunogenic, with development of antirasburicase anti-

bodies occurring in the majority of patients exposed. This

limits the use of this agent to those with severe and poorly

responsive hyperuricemia.

D. Hydration—Vigorous hydration and alkalinization of the

urine decrease the risks of urinary tract precipitation of uric

acid and may decrease hyperkalemia. Urine flow should be

maintained at a rate of more than 100 mL/h, and urine pH

should be between 7.0 and 7.5. Sodium bicarbonate or aceta-

zolamide is given to alkalinize the urine. The ideal choice of

intravenous fluid is not clear, but usually dextrose 5% in

0.45% NaCl is given with 50–100 meq of NaHCO

3

added per

liter starting 24–48 hours before treatment, if possible. A rare

complication of urinary alkalinization is precipitation of

calcium phosphate stones.

Coiffier B, Riouffol C: Management of tumor lysis syndrome in

adults. Exp Rev Anticancer Ther 2007;7:233–9. [PMID:

17288532]

Del Toro G, Morris E, Cairo MS: Tumor lysis syndrome:

Pathophysiology, definition, and alternative treatment

approaches. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol 2005;3:54–61. [PMID:

16166968]

Rampello E, Fricia T, Malaguarnera M: The management of tumor

lysis syndrome. Nat Clin Pract Oncol 2006;3:438–47. [PMID:

16894389]

Tiu RV et al: Tumor lysis syndrome. Semin Thromb Hemost

2007;33:397–407. [PMID: 17525897]

CRITICAL CARE OF THE ONCOLOGY PATIENT

463

Hyponatremia in Malignancy

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Nausea, anorexia, lethargy, confusion, weakness, con-

vulsions, coma.

Low plasma sodium with persistent excretion of con-

centrated urine.

Normal renal function with low serum urea nitrogen,

absence of fluid retention, and absence of intravascular

volume contraction.

History of malignancy, most frequently associated with

small cell carcinoma of the lung.

General Considerations

Hyponatremia in malignant disease is most often associated

with the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone

secretion (SIADH), resulting from secretion of ADH by the

tumor. SIADH causes an increase in total body water with

moderate expansion of plasma volume, hyponatremia,

plasma hypo-osmolality, and inability to excrete maximally

diluted urine. It may occur with any malignancy but is most

frequently associated with small cell carcinoma of the lung

and mesothelioma. Other causes of SIADH are the admin-

istration of thiazide diuretics, vincristine, cyclophos-

phamide, chlorpropamide, tolbutamide, carbamazepine,

intravenous opioids, and psychotropic drugs (eg, amitripty-

line and thioridazine) in the setting of treatment of the can-

cer patient.

Clinical Features

A. Symptoms and Signs—Lethargy, nausea, anorexia, and

generalized weakness are the most common symptoms. Such

symptoms, however, are nonspecific and may be caused by

the primary cancer rather than hyponatremia. Confusion,

convulsions, coma, and death may occur if hyponatremia is

severe or of rapid onset.

B. Laboratory Findings—Plasma sodium concentration is

less than 135 meq/L, and there is persistent excretion of

urinary sodium. Renal function tests are normal, and

edema and intravascular volume contraction do not occur.

Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) concentration is characteristi-

cally low.

Diagnostic criteria for SIADH include hyponatremia

with low serum urea nitrogen (<10 mg/dL), absence of

intravascular volume contraction, persistent urinary excre-

tion of sodium (>30 meq/L), absence of fluid retention such

as peripheral edema or ascites, normal renal function, and

plasma hypotonicity in the presence of urine that is not

maximally dilute (urine osmolarity >100–150 mOsm/L with

plasma osmolarity <260 mOsm/L).

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of low plasma sodium consists of

a long list that includes edematous states (eg, heart failure,

nephrotic syndrome, and cirrhosis), myxedema, salt-wasting

states (eg, mineralocorticoid deficiency, glucocorticoid

deficiency, and chronic renal failure), GI electrolyte losses

with hypotonic fluid replacement, compulsive water drink-

ing, and hypothalamic disorders. Pseudohyponatremia

secondary to hyperglycemia, mannitol administration,

and paraproteinemia should be excluded.

Treatment

Treatment of hyponatremia is discussed in Chapter 2. The

management of severe hyponatremia (plasma sodium < 110

meq/L) should be aggressive in a patient who is comatose or

convulsing, with the goal of raising plasma sodium above

120 meq/L but no higher than 130 meq/L. In other patients,

a maximum increase in plasma sodium of 8 meq/L in 24 hours

should be the target because of the complication of osmotic

demyelination syndrome.

Patients with plasma sodium levels of 125 meq/L or less

should be restricted to 500–700 mL of fluid a day. Patients

with higher plasma sodium concentrations are restricted to

1000 mL/day. Severe hyponatremia or symptomatic hypona-

tremia of any severity may require other treatment.

Administration of 0.9% NaCl will not correct hyponatremia

in patients with SIADH who have a urine osmolality of more

than 308 mOsm/L. In these patients, hypertonic saline (3%

NaCl, 1000 mL over 6–8 hours) and furosemide (40–80 mg

every 6–8 hours as needed) may be necessary. Central venous

pressure monitoring can reduce the risk of the precipitous

development of pulmonary edema. Plasma sodium and potas-

sium concentrations should be monitored hourly. Furosemide

and hypertonic saline are discontinued when plasma sodium

exceeds 110 meq/L and fluid restriction is started.

Direct antagonism of inappropriately secreted arginine

vasopressin should facilitate water elimination. Conivaptan,

a new vasopressin antagonist approved for euvolemic

hyponatremia, is given with an intravenous loading dose of

20 mg, followed by 20 mg administered as a continuous

intravenous infusion over 24 hours.

For chronic hyponatremia, demeclocycline, 150–300 mg

orally four times daily, may be given to patients who cannot

tolerate chronic fluid restriction or do not improve with fluid

restriction. Demeclocycline induces nephrotoxic diabetes

insipidus and may cause azotemia.

Adler SM, Verbalis JG: Disorders of body water homeostasis in

critical illness. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am

2006;35:873–94. [PMID: 17127152]

CHAPTER 20

464

Ellison DH, Berl T: Clinical practice: The syndrome of inappropri-

ate antidiuresis. N Engl J Med 2007;356:2064–72. [PMID:

17507705]

Oh MS: Management of hyponatremia and clinical use of vaso-

pressin antagonists. Am J Med Sci 2007;333:101–5. [PMID:

17301588]

Hypokalemia & Ectopic ACTH Secretion

A number of tumors secrete ACTH, stimulate adrenal pro-

duction of corticosteroids, and result in Cushing’s syndrome.

These tumors include small cell lung cancer; carcinoid

tumors of the bronchi, pancreas, thymus, and ovary; islet cell

tumors; and cancers of the ovary, thyroid, and prostate, as

well as pheochromocytoma, hematologic malignancies,

and sarcomas. Unfortunately, most malignant causes of

ectopic ACTH production are rapidly fatal. Patients typically

present with weakness, cachexia, and hypertension. Typical

features of nonmalignant chronic Cushing’s syndrome are

often absent.

The differential diagnosis of hypokalemia includes GI

losses associated with alkalosis, vomiting, prolonged nasogas-

tric suction, villous adenoma of the colon, Zollinger-Ellison

syndrome, and chronic laxative abuse. Hyperaldosteronism,

hypercortisolism, hypercalcemia, and licorice ingestion also

may cause hypokalemia.

The most effective treatment of hypokalemia is control of

the underlying tumor. Carcinoid, thyroid tumors, pheochro-

mocytoma, and islet cell tumors are treated surgically if they

are resectable. If the tumors are nonresectable, chemotherapy

may be used (eg, mitotane, metyrapone, ketoconazole, and

aminoglutethimide). Potassium replacement should be

accomplished as early as possible. Spironolactone, 100–400 mg

daily, is helpful.

Hypophosphatemia in Malignancy

Hypophosphatemia (serum phosphorus <3 mg/dL) is occa-

sionally associated with rapidly growing tumors (eg, acute

leukemia) and marked nutritional deprivation and cachexia.

Symptoms may include generalized weakness, respiratory

muscle weakness causing respiratory failure, decreased

myocardial function, platelet dysfunction, and leukocyte dys-

function. Hemolysis and rhabdomyolysis may occur with

serum phosphorus levels of less than 1 mg/dL. The manage-

ment of severe hypophosphatemia (serum phosphorus <1

mg/dL) consists of intravenous administration of a solution

of 30–40 mmol/L of neutral sodium phosphate or potassium

phosphate at the rate of 50–100 mL/h. Intravenous adminis-

tration of phosphates should be monitored very carefully.

Patients with mild hypophosphatemia (serum phosphorus

1–2 mg/dL) can be given inorganic phosphate supplements

orally unless severely symptomatic.

Hyperglycemia in Malignancy

Hyperglycemia not due to insulin deficiency is present in

many patients with cancer. It occurs in patients with

glucagonoma, somatostatinoma, pheochromocytoma, and

ACTH-secreting tumors. Nonketotic hyperglycemia with

hyperosmolar coma may occur as a complication of treat-

ment with cyclophosphamide, vincristine, or prednisone in

patients with mild diabetes mellitus and in patients who are

receiving hyperalimentation.

Hyperglycemia caused by a tumor may respond to treat-

ment of the primary tumor with surgical resection, radiation

therapy, or chemotherapy. Hyperosmolar coma is treated

with replacement of fluid losses (intravenous NaCl solu-

tions) and insulin administration.

Hypoglycemia in Malignancy

Hypoglycemia may be secondary to inappropriate secretion

of insulin (insulinoma) or to nonsuppressible insulin-like

substances that are produced by some tumors. Large

retroperitoneal fibrosarcomas, mesotheliomas, and renal,

adrenal, and primary hepatocellular carcinomas are the most

common tumors associated with hypoglycemia. Patients

with extensive hepatic metastases may develop severe hypo-

glycemia secondary to depletion of glycogen and impaired

gluconeogenesis. Other causes of hypoglycemia include

administration of drugs such as insulin, oral hypoglycemic

agents, alcohol, and salicylates. Starvation, chronic liver dis-

ease, hypoadrenalism, hypopituitarism, and myxedema also

may cause hypoglycemia. Pseudohypoglycemia may occur in

patients with marked granulocytosis, especially in the setting

of myeloproliferative disorders.

Tumor-associated hypoglycemia produces changes that

are characteristic of hypoglycemia in the fasting state, such as

fatigue, convulsions, or coma. On the other hand, tremors,

sweating, tachycardia, and hunger are symptoms more char-

acteristic of reactive hypoglycemia in the postprandial state.

Intravenous glucose is the treatment of choice and should

be given to all patients with blood glucose levels below 40

mg/dL and symptomatic patients with glucose levels below

60 mg/dL. Continuous infusion of 10–20% dextrose in

water should be given at a rate to maintain a blood glu-

cose level above 60 mg/dL. If blood glucose levels cannot

be increased to a safe level, prednisone, diazoxide, or

glucagon may be considered.

Lactic Acidosis

Lactic acidosis is seen in the ICU most often because of

severe hypoperfusion from septic or cardiogenic shock.

Rarely, patients with leukemia or lymphoma without obvi-

ous shock appear to have tumor overproduction of lactic

acid, possibly related to increased anaerobic metabolism

from lack of perfusion to tumor. There may be associated

CRITICAL CARE OF THE ONCOLOGY PATIENT

465

hypoglycemia. Treatment of the underlying tumor may help,

but lactic acidosis in cancer patients has a poor prognosis.

Spinazze S, Schrijvers D: Metabolic emergencies. Crit Rev Oncol

Hematol 2006;58:79–89. [PMID: 16337807]

SUPERIOR VENA CAVA SYNDROME

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Distention of neck and anterior chest wall veins.

Edema of the face; cyanosis and edema of upper

extremities.

Clinical evidence of intrathoracic malignancy.

General Considerations

There are no clinical or experimental data to support the

concept that superior vena cava obstruction is an oncologic

emergency, except perhaps on very rare occasions when the

patient presents with symptoms caused by tracheal obstruc-

tion or severe cerebral edema.

Superior vena cava syndrome was first described in 1751.

Malignant tumors are the most common cause (60%), but

recently, benign causes have increased in proportion to the

number of intravascular devices placed in the large systemic

veins in the thorax. Bronchogenic carcinoma is the leading

cause of superior vena cava syndrome and is responsible for

nearly 80% of all malignant causes. Approximately 5% of all

patients with bronchogenic carcinoma develop superior vena

cava syndrome during their lifetime, but the frequency of

this syndrome in small cell cancer is much higher. Malignant

lymphomas are responsible for approximately 15% of malig-

nant cases. Other causes (<5%) include metastatic disease to

the mediastinal lymph nodes (from primary breast and tes-

ticular cancer and, rarely, sarcomas). Benign causes are now

most commonly from complications of intravascular devices

(eg, catheters and pacemakers), with mediastinal fibrosis sec-

ondary to histoplasmosis, tuberculosis, pyogenic infection,

and radiation therapy to the mediastinum much less com-

mon. Very rarely, superior vena cava syndrome may be

caused by benign mediastinal tumors such as dermoids, ter-

atomas, thymomas, retrosternal goiters, sarcoidosis, and

aneurysms of the ascending thoracic aorta.

Malignant obstruction of the superior vena cava may be

caused by the tumor compressing its thin wall or invading it.

Thrombosis with clot formation is usually present. Collateral

circulation develops gradually. The collateral circulation

involves the internal mammary, intercostal, azygos, hemiazy-

gos, superior epigastric, and inferior epigastric veins. It

should be noted that in rapidly growing tumors, engorge-

ment of the venous collateral circulation may be absent.

Incompetence of the valves of internal jugular veins may

result only rarely in severe cerebral edema. Obstruction of

the trachea by mediastinal tumors is a serious associated

complication.

Clinical Features

The most common physical findings in superior vena cava

syndrome are neck and anterior chest wall vein distention

(60%), tachypnea (50%), edema of the face (50%), and

cyanosis and edema of the upper extremities (15%). The

diagnosis of superior vena cava syndrome is made on clinical

grounds in almost all patients. Superior vena cavography

may be used to verify the diagnosis and localize the site of

obstruction. Chest radiographs, CT scans, and MRI demon-

strate, evaluate, and define the extent of the mediastinal

lesion. Chest radiographs readily demonstrate a mass in

more than 90% of patients. MRI has no specific advantage

over CT scan in this disorder.

Although the symptoms of superior vena cava syndrome

are quite distressing to the patient, attempts to obtain a defi-

nite histopathologic diagnosis should be pursued vigorously

at the earliest opportunity. More than 60% of these patients

have small cell lung cancer or lymphomas that are appropri-

ately treated with chemotherapy, and early treatment with

radiation therapy or corticosteroids before making a definite

histopathologic diagnosis may make subsequent diagnosis

difficult or impossible. The diagnosis may be established by

sputum cytology, bone marrow biopsy, bronchoscopy, lymph

node biopsy, mediastinotomy, and anterior thoracotomy.

Mediastinoscopy with biopsy is not recommended owing to

the high incidence of severe hemorrhage, increasing neck

edema, and failure of wound healing. Adequate tissue biopsy

and a touch-preparation for pathologic examination should

be done when the diagnosis of lymphoma is suspected.

Ample data support the safety of invasive diagnostic proce-

dures in patients with superior vena cava syndrome except

those with tracheal obstruction or laryngeal edema.

Treatment

Supportive therapy should be instituted as soon as the

patient is admitted to the hospital. Upper airway obstruction

from tracheal compression with resulting hypoxia must be

addressed promptly. Corticosteroids may reduce associated

brain and possibly tracheal edema and lessen secondary

inflammatory reaction. Endotracheal intubation should be

avoided if possible in patients with tracheal obstruction to

prevent further edema. Frequently, the tracheal obstruction

is present in the more distal part of the trachea and cannot

be bypassed with endotracheal intubation. Tracheostomy is

rarely indicated for the same reasons. Placement of a self-

expanding metal endoprosthesis stent provides rapid relief

and is successful in over 90% of patients.

Chemotherapy is the treatment of choice for patients

with small cell lung cancer, lymphomas, and germ cell

tumors—more than 60% of patients with superior vena cava

CHAPTER 20

466

syndrome. Radiation therapy is the only treatment available

for other cancers. Spiral saphenous vein bypass grafting also

may be useful in selected patients. Anticoagulants and

antifibrinolytic agents are of no value and may be harmful.

Diuretics are of little help.

Overall, it has been observed that improvement in symp-

toms occurs in 50–70% of patients over a period of 1–2

weeks of treatment rather than within the first few days. It is

suggested that such improvement may be due to the develop-

ment of collateral circulation rather than to relief of the vena

caval obstruction. Studies have shown that in patients with

complete clinical symptomatic relief, the superior vena cava

lumen remained completely obstructed in 46% on venogra-

phy and in 76% at autopsy. Individual mortality is related to

the underlying malignancy rather than to the presence of

superior vena caval obstruction.

Rice TW, Rodriguez RM, Light RW: The superior vena cava syn-

drome: Clinical characteristics and evolving etiology. Medicine

(Baltimore) 2006;85:37–42. [PMID: 16523051]