Bongard Frederic , Darryl Sue. Diagnosis and Treatment Critical Care

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

CARDIAC PROBLEMS IN CRITICAL CARE

477

chronic congestive heart failure and wasting. Diagnosis and

identification of the organism are essential for proper man-

agement. Clinical features of endocarditis, including fever,

heart murmur, unexplained anemia, and peripheral or

immunologic stigmata, should alert the physician. In partic-

ular, endocarditis needs to be considered in any febrile

patient with a known history of valvular heart disease, a

pathologic murmur, or a prosthetic valve. Patients with

community-acquired Staphylococcus aureus or Streptococcus

viridans bacteremia have a high incidence of endocarditis

(20% and 80%, respectively) and should be considered to

have endocarditis until proven otherwise.

The diagnosis of endocarditis is made on clinical grounds

(see Chapter 15). Positive blood cultures are found in as

many as 90% of patients, but the frequency of this finding

depends on the type of organism and the number of blood

cultures obtained. Therefore, one should obtain an adequate

number of samples of blood for culture before starting

antibiotic therapy or specify laboratory techniques to mini-

mize the effect of antibiotics on the culture results.

Obtaining cultures for fungi, anaerobic bacteria, and fastidi-

ous or slow-growing organisms may increase the likelihood

of an etiologic diagnosis in susceptible patients.

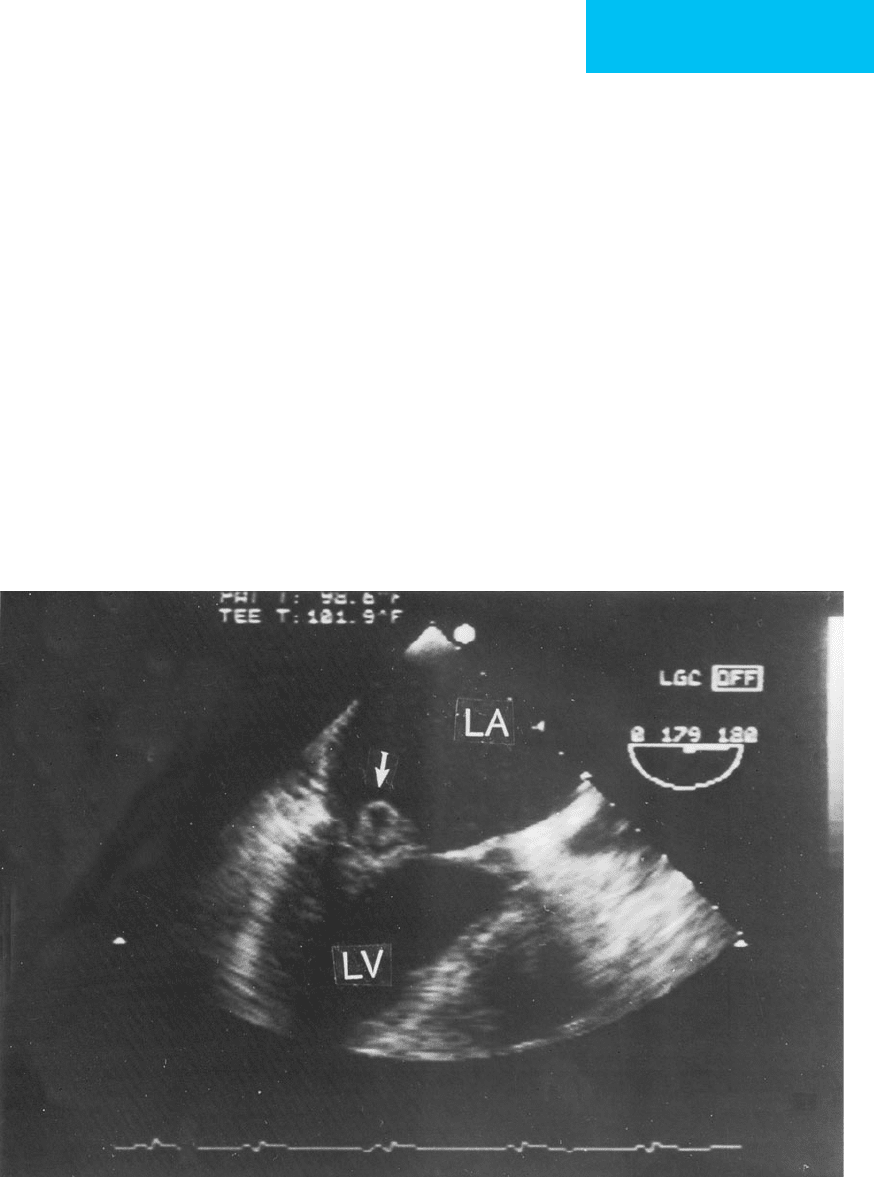

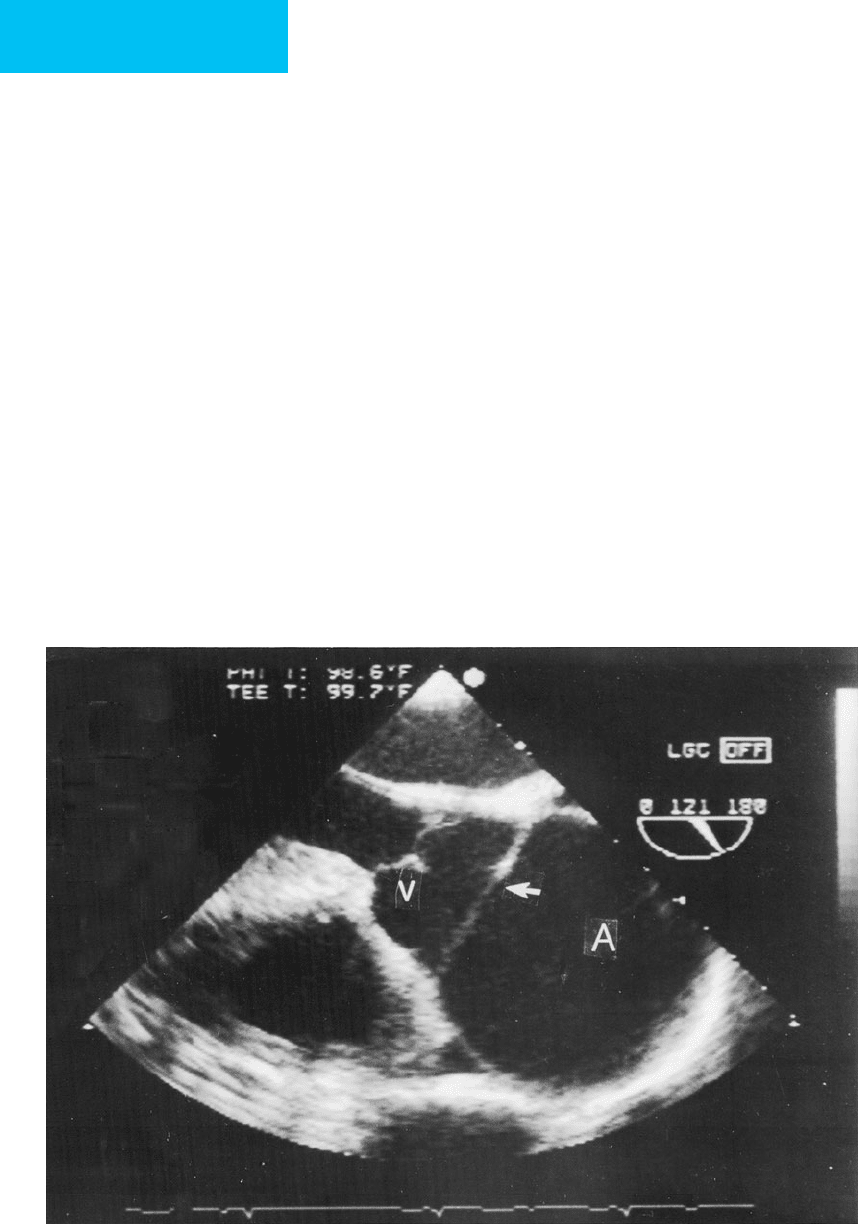

Echocardiography, especially using the transesophageal

approach, is extremely useful in detecting valvular vegeta-

tions in endocarditis and for assessing the degree of valvular

incompetence, if any (Figure 21–2).

Effective antibiotic therapy requires selection of bacterici-

dal or fungicidal drugs to which the organism is sensitive and

then delivering intravenous antibiotics in adequate quanti-

ties for a prolonged period. Fungal endocarditis is almost

never eradicated using pharmacotherapy. The duration of

therapy, in part, depends on the organism. Prosthetic valve

endocarditis often necessitates valve replacement because

antibiotics fail to eliminate the infection or because of valve

dysfunction, valve dehiscence, or ring abscess.

The outcome of both native and prosthetic valve endo-

carditis depends on cardiac function. Patients developing

congestive heart failure do quite poorly without valve

replacement. Valve replacement, even while the patient is still

Figure 21–2. Transesophageal echocardiogram demonstrating mitral valve endocarditis with a prolapsing and partial

flail mitral valve leaflet (arrow). A vegetation can be seen as well. The left ventricle and left atrium are indicated by

LV and LA, respectively. At surgery, the valve was found to be necrotic. The mitral valve was incompetent, with severe

mitral regurgitation, as seen on color-flow Doppler, but this is not shown in this still-frame image.

CHAPTER 21

478

infected or septic, can be lifesaving after congestive heart fail-

ure has developed. When to operate in cases of native valve

endocarditis depends in part on the hemodynamic conse-

quences of the infection (eg, severe valvular regurgitation,

intracardiac shunts, or congestive heart failure). Surgery is

required if antibiotic therapy fails to clear the infection, if

there are persistent fevers or a valve ring abscess, or if cul-

tures have identified a fastidious organism known to be dif-

ficult to eradicate medically. Patients who have more than

one major embolic episode with left-sided endocarditis

almost always undergo valve replacement. Larger vegeta-

tions, particularly on the left side of the heart, are associated

with higher complication rates and poorer outcomes.

In patients suspected of having infective endocarditis,

echocardiography should be performed to identify valvular

vegetations or valve destruction and to qualitatively assess the

degree of valvular regurgitation present. Echocardiography

then can be used to monitor therapy. Increase in vegetation

size, worsening of regurgitation, or the development of

mycotic aneurysms, intramyocardial abscesses, or a fistula

suggests treatment failure and the need for further interven-

tion. In patients with left-sided endocarditis, aortic valve ring

abscess, left-to-right shunts, valvular incompetence, and large

vegetations have important implications for outcome and the

need for valve surgery. Transesophageal echocardiography has

superior sensitivity for identifying valvular vegetations, valve

ring abscesses, and intracardiac shunts. It is particularly valu-

able for visualizing lesions in patients with prosthetic valve

endocarditis. For these reasons, transesophageal echocardiog-

raphy is recommended for all patients suspected of having

left-sided endocarditis, aortic valve endocarditis, or suspected

prosthetic valve endocarditis and for patients with endocardi-

tis who are hemodynamically unstable or deteriorating. The

transesophageal echocardiogram also should be used in the

preoperative and intraoperative management of these

patients to identify unsuspected pathologic findings, includ-

ing aortic-to-atrial fistulas and valve ring infection, and to

verify the adequacy of surgical repair.

Bonow RO et al: ACC/AHA 2006 guidelines for the management

of patients with valvular heart disease: A report of the American

College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force

on Practice Guidelines (writing committee to revise the 1998

guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart

disease), developed in collaboration with the Society of

Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, endorsed by the Society for

Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions and the Society

of Thoracic Surgeons. Circulation 2006;114:e84–231. [PMID:

16880336]

Baddour LM et al: Infective endocarditis: Diagnosis, antimicrobial

therapy, and management of complications: A statement for

healthcare professionals from the Committee on Rheumatic

Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease, Council on

Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Councils on

Clinical Cardiology, Stroke, and Cardiovascular Surgery and

Anesthesia, American Heart Association—Executive Summary

Circulation 2005;111:e394–434. [PMID: 15956145]

Butchart EG et al: Recommendations for the management of

patients after heart valve surgery. Eur Heart J 2005;26:2463–71.

[PMID: 16103039]

Carabello BA: Aortic stenosis. N Engl J Med 2002;346:677–82.

[PMID: 11870246]

Carabello BA: Modern management of mitral stenosis. Circulation

2005;112:432–7. [PMID: 16027271]

Enriquez-Sarano M, Tajik AJ : Aortic regurgitation. N Engl J Med

2004;351:1539–46. [PMID: 15470217]

Cardiac Tamponade

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Evidence of elevated pericardial pressure manifested as

elevated systemic venous pressure, decreased cardiac

output and hypotension; evidence of decreased periph-

eral perfusion.

Echocardiography: diastolic collapse of right ventricle, sys-

tolic collapse of right atrium, large pericardial effusion.

Pulmonary artery catheter monitoring: equalization of

right atrial, left atrial, and left ventricular end-diastolic

pressures.

General Considerations

Pericardial effusions occur in a variety of patients seen in the

ICU, including those with malignancy, tuberculosis, fungal

infections, myocardial infarction, trauma, acute and chronic

renal failure, thyroid disease, autoimmune conditions, and

more rarely, those with endocarditis or aortic dissection.

Patients after cardiac surgery can develop pericarditis and

pericardial effusions for several reasons. The size of the effu-

sion and the rapidity with which it develops are the major

determinants of its hemodynamic effects. Cardiac tamponade

ensues when adequate ventricular and atrial filling are pre-

vented by increased intrapericardial pressure owing to the

presence of a pericardial effusion. Left atrial, right atrial, left

ventricular end-diastolic, and right ventricular end-diastolic

pressures increase and equalize. Stroke volume, cardiac out-

put, and systemic blood pressure fall greatly, and patients may

develop shock with evidence of end-organ hypoperfusion.

Clinical Features

A. Symptoms and Signs—Symptoms and signs may reflect

the underlying cause of the pericardial effusion, especially if

there is inflammation of the pericardium with acute peri-

carditis. Chest pain that is pleuritic and positional suggests

this diagnosis. However, patients with tamponade need not

have chest pain, especially if tamponade is due to other

causes such as malignancy or uremia. When cardiac tampon-

ade develops, patients may have associated dyspnea and

orthopnea.

CARDIAC PROBLEMS IN CRITICAL CARE

479

Physical findings in cardiac tamponade include distended

neck veins, tachycardia, hypotension, and pulsus paradoxus.

Elevated pericardial pressure will cause distended neck veins

(which should be looked for in the upright position because

the meniscus may not be visible in a semisupine patient

when the pressures are markedly elevated), pulsus paradoxus

(ie, augmented respiratory variation in the pulse pressure,

usually >10 mm Hg), and usually hypotension. Although in

general the blood pressure is reduced, normal or elevated

blood pressure can be seen with tamponade in patients with

previous hypertension. Tachycardia, tachypnea, and orthop-

nea are important supporting signs suggesting elevated pres-

sures affecting the left side of the heart. Heart sounds as well

as the left ventricular impulse may be muted because the

heart is surrounded by fluid and farther away from the chest

wall. Hepatomegaly and peripheral edema may be present.

Patients rarely may present with “low pressure” cardiac tam-

ponade, in which classic signs may be absent but there is evi-

dence of reduced cardiac output. These patients have decreased

intravascular pressures relative to pericardial pressures, but the

diagnosis usually can be made by echocardiogram.

B. Laboratory Findings—Laboratory abnormalities may

identify a specific cause of pericardial effusion. If a diagnos-

tic pericardiocentesis is performed, a specific diagnosis may

be made from bacterial, fungal, or mycobacterial cultures;

cytologic examination; and other studies.

C. Electrocardiography—Electrocardiography may show

decreased voltage. Acute pericarditis may present with dif-

fusely elevated ST segments or PR depression on ECG.

Electrical alternans is an important clue supporting the

diagnosis of cardiac tamponade but is neither sensitive nor

specific.

D. Imaging Studies—The chest x-ray may show car-

diomegaly with a characteristic “water bottle” shape, but if

the development of pericardial effusion is rapid, heart size

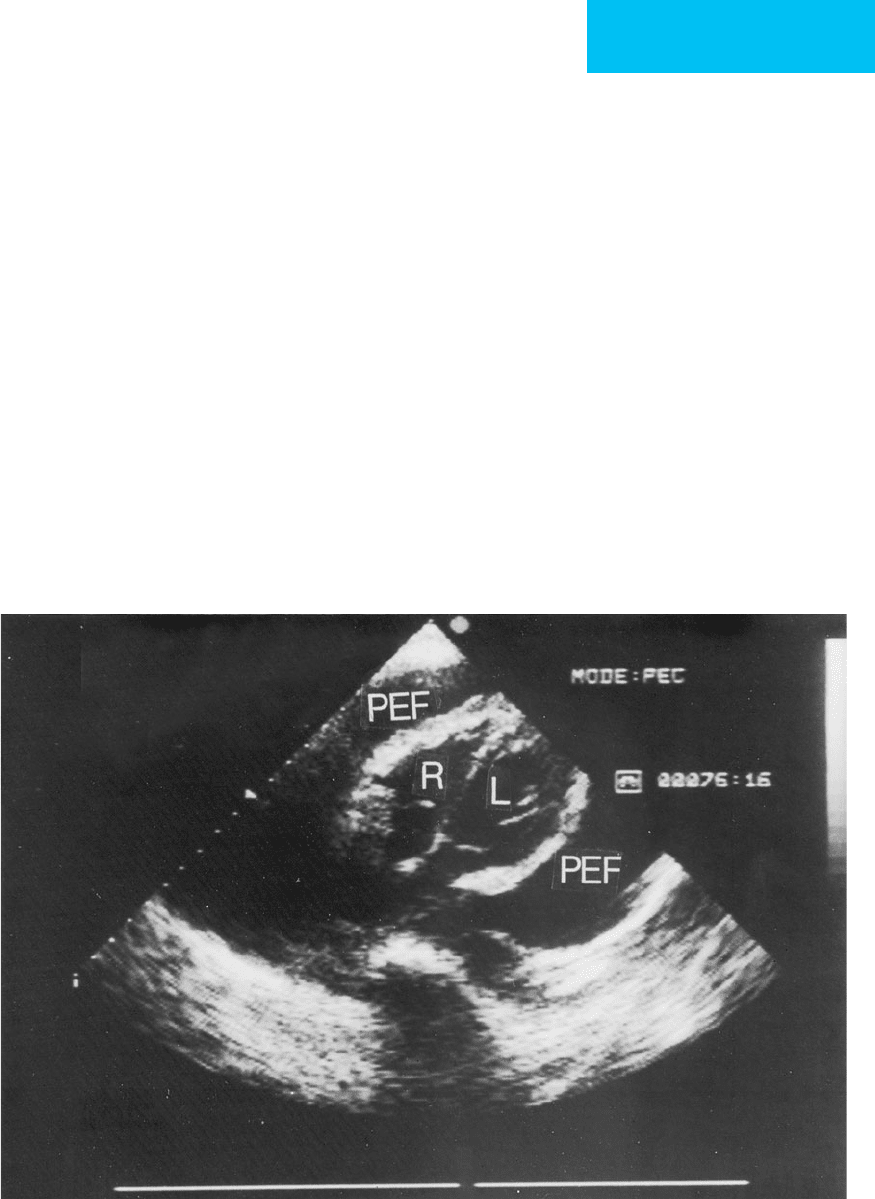

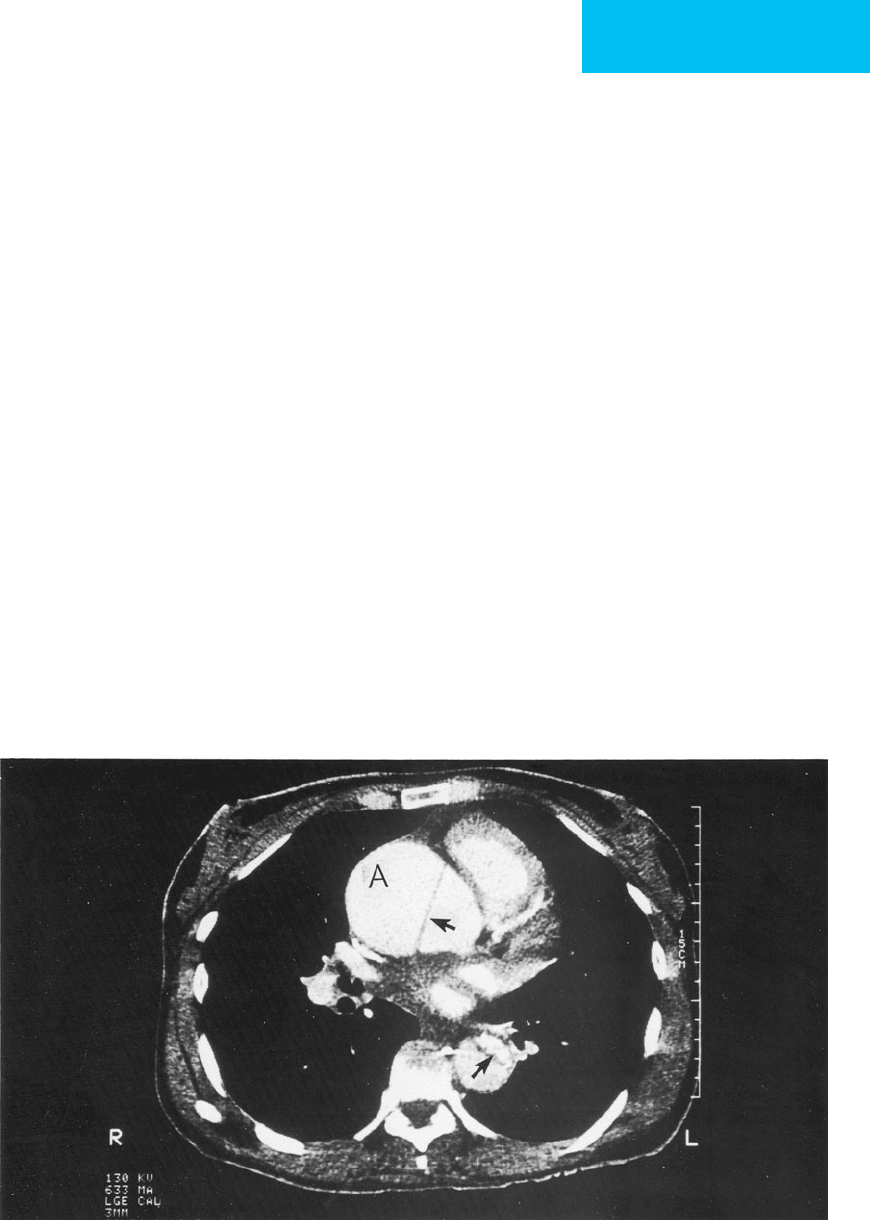

may be only slightly increased. At the bedside, echocardio-

graphy can rapidly and accurately determine if pericar-

dial fluid is present and estimate ventricular function

(Figure 21–3). In addition, there are several echocardio-

graphic criteria for the diagnosis of tamponade in patients

with pericardial effusions. These findings include the

Figure 21–3. Two-dimensional echocardiogram taken from the subcostal window demonstrating a large pericardial

effusion with cardiac tamponade. PEF locates the pericardial effusion surrounding the heart. R and L indicate the right

and left ventricles, respectively. Note that the chambers are quite small because of the massive pericardial effusion.

CHAPTER 21

480

“swinging heart,” right ventricular diastolic or right atrial

systolic collapse, respiratory variation in the left ventricular

and the right ventricular chamber sizes, and right atrial

indentation. Although helpful, these signs are neither sensi-

tive nor specific. Therefore, after identifying a moderate to

large pericardial effusion by echocardiography in a sympto-

matic patient, a bedside pulmonary artery catheter should be

placed to confirm the hemodynamic findings of tamponade.

Treatment

Initial treatment of cardiac tamponade consists of rapid

intravenous fluid loading and dopamine. The goal is to

increase intravascular pressures enough to overcome the

increased pericardial pressure as well as maintain adequate

systemic blood pressure. Although these agents may improve

the hemodynamic status for a short time, pericardiocentesis

when tamponade is present is essential to avoid hemody-

namic collapse and death. This procedure should be per-

formed rapidly to relieve the hemodynamic compromise and

to determine the cause of the effusion.

An intrapericardial catheter can be placed through a sub-

xiphoid approach using a wire placed through a thin-walled

needle (Seldinger technique). Positioning is done using elec-

trocardiographic guidance, echocardiographic guidance, or

fluoroscopy. The catheter should remain in place to permit

repeated aspirations of fluid. Fluid should be sent for cul-

ture, cytologic examination, and serologic testing. Patients

with moderate to large effusions and elevated filling pres-

sures but not satisfying the criteria for cardiac tamponade

should have hemodynamic measurements made before and

after pericardiocentesis to verify hemodynamic benefit as

well as to obtain fluid for diagnosis. Cardiac tamponade sec-

ondary to renal failure may benefit from injection of a non-

absorbable corticosteroid into the pericardial space after

drainage of the fluid.

In patients with malignant pericardial effusion and car-

diac tamponade, drainage followed by sclerotherapy using

bleomycin or fluorouracil may decrease the recurrence of

tamponade. Alternatively, balloon pericardiotomy may allow

drainage of fluid into the pleural or mediastinal space—thus

preventing reaccumulation of fluid, which would result in

tamponade. However, in patients whose life expectancy is

greater than 6 months (a small number of patients with

malignant pericardial effusions and tamponade) and in

those whose effusion cannot be controlled with sclerosis of

the pericardial space, pericardiectomy should be considered.

Lange RA, Hillis LD: Acute pericarditis. N Engl J Med 2004;351:

2195–2202. [PMID: 15548780]

Little WC, Freeman GL: Pericardial disease. Circulation 2006;113:

1622–32. [PMID: 16567581]

Maisch B et al: Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of

pericardial diseases executive summary: The task force on the

diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases of the

European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J 2004;25:587–610.

[PMID: 15120056]

Sagrista-Sauleda J et al: Low-pressure cardiac tamponade: Clinical

and hemodynamic profile. Circulation 2006;114:945–52.

[PMID: 16923755]

Spodick DH: Acute cardiac tamponade. N Engl J Med 2003;349:

684–90. [PMID: 12917306]

Hypertensive Crisis & Malignant

Hypertension

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Hypertensive crisis: systemic blood pressure >240/130

mm Hg without symptoms or elevated blood pressure

with chest pain, headache, or heart failure; may have

intracranial hemorrhage, aortic dissection, pulmonary

edema, myocardial infarction, or unstable angina.

Malignant hypertension: severe hypertension associated

with encephalopathy, renal failure, or eye findings

including retinal hemorrhage, exudates, or papilledema.

General Considerations

Hypertension in adults is usually a chronic condition that, if

untreated, is a significant risk factor for the long-term devel-

opment of coronary, cerebral, and peripheral vascular disease.

Mild to moderate hypertension usually poses no immediate

danger to the patient if the pressure is below 170/110 mm Hg.

Patients with mild to moderate hypertension are often

asymptomatic, and control of their blood pressure can be

achieved using oral medications and modification of diet.

Antihypertensive treatment usually is begun on an outpatient

basis after documentation of persistent hypertension and

evaluation for potentially reversible causes.

A subset of patients present with or develop severe life-

threatening hypertension or have other coexisting medical

problems requiring urgent control of blood pressure; these

patients are defined as having a hypertensive crisis (some-

times called a hypertensive emergency). For example, patients

with acute myocardial infarction or unstable angina benefit

greatly from reduction of elevated blood pressure and lower-

ing of left ventricular afterload. Blood pressure represents a

major factor in myocardial oxygen demand. When conges-

tive heart failure owing to left ventricular dysfunction or aor-

tic or mitral regurgitation is associated with severe

hypertension, rapid lowering of blood pressure will acceler-

ate treatment of the hemodynamic dysfunction. Patients

with acute aortic dissection and elevated blood pressure have

greatly increased stress on the aorta, and urgent control of

blood pressure is mandatory. Patients with intracranial

hemorrhage—intracerebral or subarachnoid—also require

control of blood pressure and may become acutely hyperten-

sive as a result of the CNS event. Severe hypertension results

in local and systemic effects that start a cascade of events that

CARDIAC PROBLEMS IN CRITICAL CARE

481

further elevates blood pressure. Dilation of cerebral blood

vessels results in hypertensive encephalopathy, and damage

to the blood vessel wall can increase permeability, resulting

in edema or bleeding.

Malignant hypertension is defined by some as severe

hypertension associated with specific end-organ damage,

namely encephalopathy, nephropathy, or eye findings,

including retinal hemorrhages, exudates, or papilledema.

Treatment of malignant hypertension is important because

rapid and effective lowering of blood pressure is essential for

reversal of complications.

Any of the causes of hypertension can be associated with

hypertensive crisis, including essential, renovascular, or

endocrine-mediated (eg, pheochromocytoma) forms of

hypertension. Most patients who present with hypertensive

crises have preexisting hypertension.

Clinical Features

A. Symptoms and Signs—Patients with severely elevated

blood pressure are frequently asymptomatic, but most will pres-

ent with headache, confusion, stupor, seizure, or coma depend-

ing on the severity of the hypertension and the degree of

end-organ involvement. Chest pain may be due to angina pec-

toris, unstable angina, or myocardial infarction associated with

hypertension, but chest pain also should raise the possibility of

aortic dissection. In malignant hypertension, papilledema, reti-

nal hemorrhages, or exudates are present by definition and may

be accompanied by encephalopathy. Acute oliguric renal failure

as well as signs and symptoms of congestive heart failure may be

seen. The blood pressure is usually quite elevated, with diastolic

blood pressure exceeding 130 mm Hg. Ophthalmoscopic exam-

ination may demonstrate retinal hemorrhages and exudates as

well as papilledema. Patients may have evidence of congestive

heart failure. Neurologic findings owing to severe hypertension

may include focal motor or sensory abnormalities as well as

altered mental status. However, other causes of acute neurologic

impairment with hypertension must be excluded, including pri-

mary CNS events such as strokes, tumors, head injury,

encephalitis, and collagen vascular disease.

B. Laboratory Findings—Serum creatinine and urea nitro-

gen may be elevated. In those with acute hypertensive

nephropathy, urinalysis shows red blood cells, red blood cell

casts and proteinuria.

C. Electrocardiography—Electrocardiography may show left

ventricular hypertrophy, particularly with chronic hyperten-

sion. Acute ST-segment and T-wave changes may be second-

ary to hypertension but also may represent acute ischemia.

D. Imaging Studies—The chest x-ray may show car-

diomegaly and pulmonary edema. Aortic dissection should

be considered when reviewing the film. Imaging of specific

organs depends on symptoms and signs and may include

head CT scan (eg, strokes and focal neurologic findings),

renal ultrasound (eg, acute renal insufficiency), and

echocardiography (eg, aortic dissection).

Treatment

The most important consideration in patients with hyper-

tensive crisis is rapid reduction of blood pressure with a

short-acting, easily titratable agent. The goal is to prevent

permanent vascular and neurologic damage and to avoid

worsening the heart failure or causing uncontrollable

hypotension. Blood pressure should be controlled aggres-

sively in these patients, and therapy should be instituted even

while etiologic investigation is still under way. Of particular

concern, patients with strokes or other types of neurologic

dysfunction may sustain further neurologic damage if blood

pressure is lowered too abruptly or excessively. Therefore,

the initial goal of antihypertensive therapy within the first

6 hours is to lower the blood pressure by 25% of the starting

blood pressure value or to no less than 150/110 mm Hg.

Further lowering should take place more gradually.

A. Nitroprusside—Intravenous nitroprusside, which acts as

a peripheral arteriodilator, is the drug of choice in hyperten-

sive crises because it can be titrated rapidly and safely.

Excessive hypotension can be avoided by careful blood pres-

sure monitoring, usually with an arterial catheter, but a non-

invasive automated cuff manometer is usually satisfactory. If

hypotension occurs with nitroprusside therapy, discontinu-

ation of the drug results in rapid restoration of blood pres-

sure. Nitroprusside is given intravenously at a rate of

0.25–10 μg/kg per minute. Usually one begins at a low infu-

sion rate and adjusts the rate as needed every 5 minutes over

a period of 1–2 hours. Thiocyanate toxicity can occur, par-

ticularly in patients with renal failure. However, over the

first 24 hours, when control of blood pressure is essential,

this is not a major concern. After blood pressure is lowered

to a satisfactory level, institution of oral antihypertensive

drugs is begun with the goal of discontinuing nitroprusside

within 24–48 hours.

B. Other Antihypertensive Agents—Other parenteral

agents that can be used in patients with severe hypertension

include esmolol, hydralazine, labetalol, nitroglycerin (usually

a mild blood pressure–lowering agent), and enalaprilat, an

ACE inhibitor. Esmolol is a short-acting β-adrenergic blocker

indicated for short-term use. It should be avoided in patients

with bronchospasm, severe heart failure, heart block, or

bradycardia. Hydralazine is a peripheral vasodilator that can be

given orally or intravenously. Reflex tachycardia is common, and

β-adrenergic blockers are almost always given simultaneously.

Labetalol has both α- and β-adrenergic blocking effects.

Nitroglycerin has primarily venodilator effects. The degree of

lowering of blood pressure with intravenous nitroglycerin varies

from patient to patient, and there is some risk of lowering car-

diac output excessively with this drug. On the other hand, nitro-

glycerin has the advantage of being a coronary artery

vasodilator and therefore is useful in patients with hypertension

and myocardial ischemia. Enalaprilat is the only intravenous

ACE inhibitor available. It is converted to the active drug

enalapril after infusion. It has modest antihypertensive effects

CHAPTER 21

482

at the dosages recommended (starting dose 0.625 mg). Side

effects include worsening of renal failure and hyperkalemia.

Oral calcium channel blockers, including amlodipine and

diltiazem, are useful in less severe hypertension. In patients

with severe hypertension and heart failure, calcium channel

blockers and beta-blockers may result in unacceptable depres-

sion of ventricular function, in some cases worsening conges-

tive heart failure. However, β-adrenergic blockers must be

used in patients with dissecting aortic aneurysms before sys-

temic vasodilators (eg, hydralazine and nitroprusside) are

given to prevent an increase in shear stress on the aortic wall.

Diuretics may be needed in addition to the antihypertensive

medication to help relieve the volume overload associated

with treatment with many of the vasodilator drugs.

Stable patients with severe hypertension without

encephalopathy may be managed with oral agents, including

beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers, clonidine,

hydralazine, and ACE inhibitors. Combinations of drugs are

often necessary to maximize effects and minimize side effects

and toxicities.

Aggarwal M, Khan IA: Hypertensive crisis: Hypertensive emergen-

cies and urgencies. Cardiol Clin 2006;24:135–46. [PMID:

16326263]

Chobanian AV et al: The seventh report of the Joint National

Committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment

of high blood pressure: The JNC 7 report. JAMA

2003;289:2560–72. [PMID: 12748199]

Feldstein C: Management of hypertensive crises. Am J Ther 2007;14:

135–9. [PMID 17414580]

Marik PE, Varon J: Hypertensive crises. Chest 2007;131:1949–62.

[PMID: 17565029]

Complications of Cardiac Catheterization

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Bleeding or thrombosis at vascular access site.

Peripheral arterial emboli from clot at access site.

CNS complications from cerebrovascular emboli.

Arrhythmias, myocardial infarction, cardiac tamponade

from myocardial perforation, aortic dissection.

General Considerations

Patients may be admitted to the ICU after cardiac catheteri-

zation for monitoring or because of complications from the

procedure. Complications may result from the underlying

cardiac problem, but complications from the cardiac

catheterization procedure itself should be anticipated.

Complications can be grouped into problems related to the

vascular access site, the aorta, and the heart.

A. Vascular Access Complications—Vascular access, partic-

ularly in an atherosclerotic vessel, can result in the development

of dissection or occlusion at the vascular site or may provide

a nidus for thrombus with or without peripheral emboliza-

tion. In addition, large hematomas may develop at the entry

site if adequate hemostasis is not achieved or if vascular

damage with a pseudoaneurysm or intimal tear has

occurred. The use of heparin, clopidogrel, aspirin, and glyco-

protein IIb/IIIa receptor inhibitors for treatment of unstable

angina and prolonged catheter placement after catheteriza-

tion have increased the risk of bleeding and the need to pay

close attention to local hemostasis. Several kinds of devices

have been developed to close arterial catheter puncture sites

when catheterization is completed, including those with

arterial sutures and devices that provide internal compres-

sion with a collagen plug. These devices have reduced the risk

of bleeding significantly.

In patients with bleeding at the access site, the hematoma

should be measured, outlined with a marker, and then

observed for any increase in size. An enlarging hematoma or

swelling at the access site indicates a need for rapid evalua-

tion to exclude or control significant bleeding. Distal periph-

eral pulses, leg temperature, and the arterial site should be

checked and findings recorded frequently. Doppler studies

are indicated if changes occur or pain develops in the distal

portion of the extremity or if a pseudoaneurysm or dissec-

tion is suspected. Patients undergoing percutaneous translu-

minal coronary angioplasty (PTCA) and stent placement

may have the arterial sheath left in place for 12–24 hours or

may undergo repeat catheterizations to treat multiple

lesions. These repeat and prolonged interventions may

increase the risk of complications and require diligent anti-

coagulation to avoid arterial thrombosis. Newer coated stents

have improved outcomes dramatically with angioplasty and

higher patency rates but require prolonged treatment with a

combination of clopidogrel and aspirin. Discontinuation of

these agents, in particular clopidogrel, can result in acute

stent thrombosis and abrupt myocardial infarction. This

complicates the management of bleeding complications after

catheterization and also poses problems for ICU patients

requiring surgical noncardiac interventions where postoper-

ative bleeding may be an issue.

B. CNS Complications—Strokes can occur during and after

cardiac catheterization because of embolization of intracar-

diac thrombi, aortic intimal plaque disruption, catheter

thrombosis and embolization, and more rarely, dissection of

carotid arteries or air injected inadvertently during catheter-

ization. Strokes owing to catheterization are not infrequent

occurrences. A careful neurologic evaluation prior to cardiac

catheterization makes evaluation after catheterization more

useful. Interpretation of neurologic findings can be compli-

cated by the use of sedation for catheterization; however, a

localizing finding such as hemiplegia or aphasia is highly

suggestive of postcatheterization embolization. A CT scan or

MRI of the head or cerebral arteriography should be per-

formed immediately to help determine whether the event is

associated with hemorrhage. In the absence of hemorrhage,

intervention with thrombolysis is an option to lyse the clot.

CARDIAC PROBLEMS IN CRITICAL CARE

483

This can be done by localized infusion during cerebral

angiography or with systemic thrombolytic agents.

Prolonged use of heparin or use of other anticoagulants dur-

ing catheterization may preclude the use of systemic throm-

bolysis, and decisions are made on an individual basis with

the help of a stroke team.

C. Other Complications—Cardiac complications related to

catheterization include myocardial infarction, arrhythmias,

cardiac tamponade, and aortic dissection. Echocardiography

should be performed with little hesitation in patients com-

plaining of dyspnea or chest pain after catheterization, and

this technique can be useful to look for new cardiac wall

motion abnormalities, aortic dissection, or the development

of a pericardial effusion.

Pericardial effusions developing after catheterization are

relatively rare but require close observation for develop-

ment of tamponade, particularly in patients who have had

interventions (eg, angioplasty) or are receiving platelet

inhibitors or anticoagulation. Tamponade with hemody-

namic collapse can develop rapidly in these situations.

Acute shortness of breath with chest pain may be due to

acute ischemia, and this must be differentiated from acute

cardiac tamponade.

Radiologic contrast medium–related problems include

histamine-mediated reactions (eg, urticaria, angioedema,

and hypotension), volume depletion and hypotension sec-

ondary to the osmotic diuresis, and acute renal failure. Close

monitoring of patients after cardiac catheterization requires

attention to electrolyte and fluid balance. Patients with dia-

betes and preexisting renal disease are at increased risk of

acute renal failure. Urticaria and other histamine reactions

can be reduced by pretreatment with antihistamines and H2-

blockers one hour before the procedure. Patients with known

allergic reactions to contrast media also should be pretreated

with corticosteroids 8–12 hours before the procedure.

Hydration before and after contrast administration is the

best way to prevent renal failure. Patients with renal insuffi-

ciency or preexisting diabetes may have a reduced risk of fur-

ther deterioration if given acetylcysteine prior to the

administration of contrast material.

Becker CR et al: High-risk situations and procedures. CIN

Consensus Working Panel. Am J Cardiol 2006;98:37–41S.

[PMID: 16949379]

Chandrasekar B et al: Complications of cardiac catheterization in

the current era: A single-center experience. Catheter Cardiovasc

Interv 2001;52:289–95. [PMID: 11246238]

McCullough PA et al: Risk prediction of contrast-induced

nephropathy. CIN Consensus Working Panel. Am J Cardiol

2006;98:27–36. [PMID: 16949378]

Marenzi G et al. N-Acetylcysteine and contrast-induced nephropa-

thy in primary angioplasty. N Engl J Med 2006;354:2773–82.

[PMID: 16807414]

Pannu N, Wiebe N, Tonelli M: Prophylaxis strategies for contrast-

induced nephropathy. Alberta Kidney Disease Network. JAMA

2006;295:2765–79. [PMID: 16788132]

Aortic Dissection

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Severe chest pain without features of ischemic heart

disease in the presence of hypertension.

Widened mediastinum on chest x-ray.

Aortic dissection identified by echocardiogram, CT scan,

or MRI.

General Considerations

Acute aortic dissection is seen in patients with underlying

atherosclerotic vascular disease, hypertension, and connec-

tive tissue abnormalities such as Marfan’s syndrome. Aortic

dissection is the acute development of a tear in the intima of

the aorta. Arterial blood under high pressure enters the

intima, extending the tear and causing progressive destruc-

tion of the aortic media. This process is potentially cata-

strophic. The path the dissection takes is quite variable,

spiraling superiorly and retrograde to the aortic valve and

the coronary arteries, antegrade to the abdominal aorta, or

both. The hemodynamic manifestations and clinical findings

will depend on the path the dissection takes.

Dissections occur most frequently in the ascending aorta

near the aortic valve or in the proximal descending aorta beyond

the takeoff of the left subclavian artery. There are several classifi-

cation systems for describing the location of aortic dissection.

The easiest to understand and most relevant in terms of clinical

decision making divides aortic dissections into two types. The

proximal or ascending (type A) dissection involves the proximal

aorta but may extend beyond the aortic arch. This type is analo-

gous to the DeBakey type I and type II classification of aortic dis-

sections. Descending or distal (type B) dissection involves only

the descending portion of the aorta, similar to DeBakey type

III. Type A dissections are often lethal, causing acute aortic insuf-

ficiency, congestive heart failure, pericardial effusions, often with

tamponade, and acute myocardial infarctions. Treatment is

almost always surgical. Type B dissections are initially treated

medically but may require surgery after stabilization.

Clinical Features

A. Symptoms and Signs—The most common clinical pres-

entation of patients with aortic dissections is the abrupt onset

of severe chest or back pain. The pain is at maximum intensity

at onset. The pain tracks the progression or pathway of the dis-

section and often is described as tearing or ripping in quality.

The severity of the pain may precipitate vagal reflexes, includ-

ing hypotension and bradycardia. If the aortic valve or coro-

nary arteries are involved, congestive heart failure or myocardial

ischemia can develop acutely. Cardiac tamponade may occur

if the tear extends into the proximal aortic root, allowing blood

to enter the pericardial space. Physical findings include dimin-

ished or unequal peripheral pulses and blood pressures.

CHAPTER 21

484

A murmur of aortic regurgitation may be heard along with

findings consistent with acute pulmonary edema or tamponade.

In this age of thrombolytic therapy and anticoagulation

for acute myocardial infarction, it is critically important to

distinguish aortic dissection from myocardial ischemia.

Although both present with chest pain, the pattern of pain—

quality, location, duration, and onset—should help to distin-

guish between the two. Pain from aortic dissection is more

abrupt in onset, more often reaches maximum intensity

immediately, and is often described as tearing in quality.

Location is more often in the back than substernal. Unlike

myocardial pain, the pain of aortic dissection usually does not

respond to nitrates or beta-blockers acutely but may do so if

a reduction in blood pressure decreases the stress on the

aorta. Also unlike myocardial ischemia, aortic dissection pain

usually is unrelated to activity. In contrast, ischemic pain usu-

ally begins slowly and increases in intensity. It radiates to the

neck, jaw, and arm but never below the umbilicus. Beta-

adrenergic blockers and nitrates usually relieve ischemic pain,

although not necessarily the pain of myocardial infarction.

Ischemia and infarction often have electrocardiographic find-

ings of ST-segment and T-wave changes. On examination, the

presence of a new aortic diastolic murmur, unequal peripheral

pulses, and absence of rales in a patient with chest pain

should raise the question of aortic dissection.

If aortic dissection is a consideration, diagnostic tests

should be undertaken expeditiously because the treatment—

lowering the blood pressure, decreasing myocardial contractil-

ity with beta-blockers, and surgical repair—must be adminis-

tered urgently. Anticoagulation and thrombolytic therapy are

clearly contraindicated. Unfortunately, because aortic dissec-

tion can cause acute myocardial infarction by involving coro-

nary arteries in the dissection, the distinction between aortic

dissection and myocardial ischemia is not always clear.

B. Imaging Studies—Initial evaluation with chest x-ray may

identify a widened mediastinum, but more definitive infor-

mation can be obtained using transthoracic echocardiogra-

phy. Although the sensitivity for identifying aortic dissection

is relatively low with transthoracic echocardiography, this test

provides other useful additional information on cardiac func-

tion, ventricular wall motion, and valvular abnormalities and

can identify the presence of pericardial effusion. In addition,

the echocardiogram can be used to measure the aortic root

size, and Doppler echocardiography can determine the degree

of aortic valvular regurgitation (Figure 21–4).

Figure 21–4. Aortic dissection and aneurysm with an intimal flap demonstrated by transesophageal echocardiogra-

phy. The aneurysm of the ascending aorta is at A. The aortic valve is at V. The arrow points to the intimal flap approxi-

mately 2 cm above the aortic valve in the proximal ascending aorta.

CARDIAC PROBLEMS IN CRITICAL CARE

485

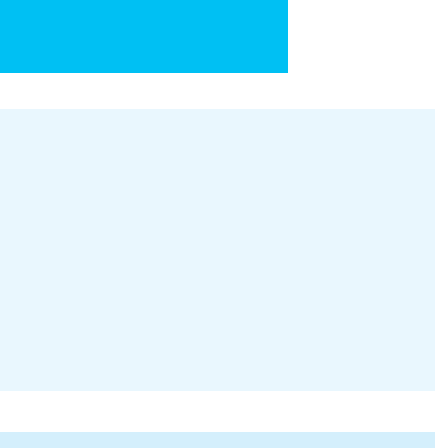

Transesophageal echocardiography, MRI, and CT scan are

80–100% sensitive and specific for the diagnosis of aortic dissec-

tion. MRI is probably the most sensitive and specific procedure,

but the availability of transesophageal echocardiography and

the ability to monitor the patient more closely during echocar-

diography than during MRI or CT scanning are important con-

siderations. Monitoring patients during MRI scanning can be

difficult, and unstable or hypotensive patients should undergo

transesophageal echocardiography at the bedside instead. One

of these tests should make the diagnosis rapidly (Figure 21–5).

If the imaging technique identifies aortic dissection, therapy is

based on the location of the dissection and the extent of aortic

involvement. Further studies may be indicated to assess coro-

nary anatomy and aortic valve function. Cardiac catheterization

may be needed to help guide the surgical intervention.

Treatment

In general, type A aortic dissections require surgery because

medical management alone for proximal ascending aortic

dissection has a high short-term and 1-year mortality rate.

Type B aortic dissections that involve the descending portion

of the thoracic aorta only are managed medically unless there

is compromise of the renal or mesenteric circulations.

Complicated dissections involving the arch and arch vessels

have high surgical and medical mortality rates, making ther-

apeutic decisions more difficult.

Immediate management of all aortic dissections

requires aggressive medical and pharmacologic therapy to

reduce systolic blood pressure and to decrease the peak

systolic velocity of aortic blood flow and thereby reduce

sheer forces on the aortic wall. The goals of therapy

include control of pain, reduction of systolic blood pres-

sure to 100–120 mm Hg (as long as renal, myocardial, and

cerebral perfusion is maintained), and stabilization of the

patient’s hemodynamic variables to permit a thorough

diagnostic evaluation. Beta-adrenergic blockers are used

aggressively to decrease the force of ventricular contrac-

tion. Heart rate is used as a guide to the degree of beta-

blockade, and enough β-adrenergic blockade should be

given to lower the heart rate to 55–65 beats/min.

Nitroprusside is used to control blood pressure initially

and is adjusted as required when beta-blockade is

achieved. Calcium channel blockers, because of their neg-

ative inotropic and antihypertensive properties, are ideal

alternatives in patients who are unable to tolerate beta-

blockers. Hydralazine and other direct vasodilators should

not be given to control blood pressure in the absence of β-

adrenergic blockade. Although blood pressure will fall, the

force of aortic blood flow may increase, further increasing

stress on the damaged aortic wall.

Survival rates approach 80–90% when appropriate ther-

apy is instituted rapidly in both type A and type B aortic dis-

sections. Outcome is determined in part by the degree of

damage to vital organs (eg, kidneys, brain, heart, and bowel),

the underlying condition of the aorta, and the extent of the

repair needed.

Figure 21–5. Aortic dissection and aneurysm with an intimal flap as demonstrated by ultrafast CT scan in the same

patient as shown by transesophageal echocardiography in Figure 21–4. The arrows point to the intimal flap. The

aneurysm is marked by an A.

CHAPTER 21

486

Ince H, Nienaber CA: Diagnosis and management of patients with

aortic dissection. Heart 2007;93:266–70. [PMID 17228080]

Khan IA, Nair CK: Clinical, diagnostic, and management perspec-

tives of aortic dissection. Chest 2002;122:311–28. [PMID:

12114376]

Mukherjee D, Eagle KA: Aortic dissection: An update. Curr Probl

Cardiol 2005;30:287–325. [PMID: 15973249]

Shiga T et al: Diagnostic accuracy of transesophageal echocardio-

graphy, helical computed tomography, and magnetic resonance

imaging for suspected thoracic aortic dissection: Systematic

review and meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1350–6.

[PMID: 16831999]

Tsai TT, Nienaber CA, Eagle KA: Acute aortic syndromes.

Circulation 2005;112:3802–13. [PMID: 16344407]

ATRIAL ARRHYTHMIAS

Critically ill patients—particularly those with pulmonary

disease and respiratory failure—are at high risk for develop-

ing atrial arrhythmias. Atrial distention, electrolyte imbal-

ances, hypoxemia, and high catecholamine levels all

contribute to electrical instability and increased atrial auto-

maticity. Identifying the type of supraventricular arrhythmia

is essential in choosing the correct treatment. A 12-lead ECG

permits more careful evaluation of P-wave morphology and

axis than a single-lead ECG from the bedside monitor or

“rhythm strip.” The morphology of the ST segments and T

waves should be examined for evidence of ischemia. The PR

interval and initial activation of the QRS segment can iden-

tify the presence of an atrioventricular (AV) nodal bypass

tract and show evidence of preexcitation.

Treatment is directed primarily toward eliminating or

reversing the precipitating or exacerbating causes.

Correction of alkalosis, hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia, or

hypoxemia will increase the likelihood of rate control and

eventual conversion to sinus rhythm. The major goal of acute

treatment is to slow the ventricular rate so as to improve car-

diac output and blood pressure. In the setting of hemody-

namic compromise (eg, hypotension, syncope, chest pain, or

electrocardiographic evidence of ischemia), rapid treatment

using electrical cardioversion may be indicated. This treat-

ment also should be performed immediately if the ventricu-

lar rate is extremely rapid or the patient will not tolerate

prolonged tachycardia because of other conditions such as

aortic or mitral stenosis, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, or

unstable angina. The high likelihood of recurrence of these

arrhythmias makes rhythm identification and appropriate

pharmacologic treatment important even if initially cor-

rected by electrical cardioversion.

AV Nodal or Reentrant Tachycardia

AV nodal reentrant (circus movement) tachycardias are

rhythm disturbances that depend on the properties of the AV

node for initiation and propagation. The arrhythmia results

from an endless circle of electrical impulses conducted down

one pathway and up another with slow and fast pathways

cooperating to facilitate and maintain the circuit. Alteration of

refractoriness or conduction velocities in either pathway in the

AV node can stop the arrhythmia immediately. The arrhyth-

mia can be prevented by altering the electrical properties of

the involved pathways or by decreasing the frequency of the

premature atrial contractions that often initiate the cycle.

AV nodal reentrant tachycardias usually have ventricular

rates of 140–220 beats/min, and AV conduction is usually 1:1

but rarely 2:1. The P wave may not be obvious if atrial and

ventricular depolarization occur simultaneously, although a

retrograde P wave may be seen. The differential diagnosis

includes sinus tachycardia, atrial tachycardia, atrial flutter, and

orthodromic AV reentry using an accessory pathway. If the

diagnosis is unclear, adenosine (6–12 mg intravenously) usu-

ally will stop either AV nodal reentry or AV reentry causing the

ventricular rate to fall all at once to the underlying sinus rate

and rhythm. A brief intervening period of sinus bradycardia or

complete heart block may occur. Sinus tachycardia will slow

gradually in response to adenosine and then return to the pre-

treatment rate. If the rhythm is atrial tachycardia, atrial flutter,

or atrial fibrillation, increasing AV block with adenosine usu-

ally will make the diagnosis apparent.

AV nodal reentrant tachycardias are treated effectively

with adenosine (6–12 mg IV bolus), verapamil (5 mg IV

bolus), diltiazem (0.25 mg/kg infusion given over 2 minutes),

or β-adrenergic blockers (eg, metoprolol, 5 mg intravenously

up to a total of three doses given every 5 minutes if needed).

These drugs alter conduction velocity through the AV node.

Because of adenosine’s extremely short half-life (measured in

seconds), it is the drug of choice for acute treatment of narrow-

complex tachyarrhythmias, but it is not useful in preventing

recurrences. Therefore, if the risk of recurrence is great in

patients with an underlying predisposing medical condition,

one of the other drugs can be administered to decrease the

likelihood of recurrence and can be tried if adenosine fails to

convert the patient to sinus rhythm. In patients with com-

promised ventricular function, digoxin may be a more

appropriate long-term drug than either calcium channel

blockers or β-adrenergic blockers, both of which are myocar-

dial depressants.

Procainamide is effective in treating atrial arrhythmias by

preventing premature atrial beats and decreasing atrial auto-

maticity. When the AV reentry tachycardia uses concealed

retrograde conduction through a bypass tract, procainamide

also may help by slowing conduction through the bypass

tract. A bypass tract may be suspected when the ventricular

rate exceeds 200 beats/min in an adult or when a baseline

ECG demonstrates a short PR interval and evidence of pre-

excitation. Digoxin, β-adrenergic blockers, and calcium

channel blockers can be dangerous in patients with bypass

tracts who have atrial fibrillation because these drugs block

AV nodal conduction and thereby facilitate conduction

through the bypass tract. The ventricle is bombarded by an

increased number of impulses from the atria, resulting in a

very rapid ventricular rate. Ventricular fibrillation may