Bongard Frederic , Darryl Sue. Diagnosis and Treatment Critical Care

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

BLEEDING & HEMOSTASIS

427

Differential Diagnosis

The finding of a normal platelet count in the presence of pal-

pable or nonpalpable purpuric skin lesions (eg, ecchymoses

or petechiae) should suggest the possibility of increased

intravascular pressure, abnormalities or injury to blood ves-

sels (eg, vasculitis), thromboembolic events (including septic

thromboemboli), decreased integrity of the microcirculation

and its supporting structures, or primary cutaneous diseases.

Severe coagulation disorders may result in mucocutaneous

bleeding but are easily distinguished from thrombocytopenia

by the presence of markedly prolonged coagulation times

and quantitatively normal platelets. Impaired platelet func-

tion and vWD should be considered when easy bruising and

mucosal bleeding are present and can be identified in most

cases by prolongation of the bleeding time in the absence of

thrombocytopenia. Abnormalities of coagulation or platelet

function rarely result in petechial skin lesions.

Treatment

The most important aspect of treatment is to reverse the

underlying disease process. Platelet transfusions should be

given only when the risk of bleeding and the probability of

efficacy are sufficient to warrant the potential risks of blood

component therapy. Prophylactic platelet transfusions are

indicated for patients with decreased production of platelets

with counts under 10,000/μL to prevent fatal CNS hemor-

rhage. When life-threatening bleeding is present or invasive pro-

cedures are required, platelet transfusions may be useful if the

platelet count is less than 50,000/μL and no alternative therapies

are available. When decreased platelet survival is present,

platelet transfusions are not likely to effect a sustained rise in

platelet count and should only be given if life-threatening bleed-

ing is present or if an urgent invasive procedure is required.

Platelet transfusions may be harmful in patients with throm-

botic thrombocytopenic purpura–hemolytic uremic syndrome

and heparin-associated thrombocytopenia and should be

avoided unless active, life-threatening hemorrhage is present.

Medications such as aspirin that impair platelet function

should be avoided when thrombocytopenia is present—with

the exception of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, in

which antiplatelet agents may be indicated as part of therapy.

Correction of severe anemia may decrease clinical bleeding in

thrombocytopenic patients. Antifibrinolytic agents such as

aminocaproic acid or tranexamic acid may decrease mucosal

bleeding in chronically thrombocytopenic patients but should

not be used if there is evidence of thrombosis (eg, in DIC) or

hematuria. Alternatives to platelet transfusion for patients

with bleeding owing to thrombocytopenia are outlined in

Table 3–2.

Current Controversies and Unresolved Issues

Intravenous administration of human immunoglobulin

(IVIG) may rapidly increase the platelet count in patients with

immune-mediated thrombocytopenia. Its effect is postulated

to be due to competitive blockade of macrophage receptors

for immunoglobulin, although other mechanisms may be

important. Although it may rapidly increase the platelet

count, its usefulness as therapy for immune thrombocytope-

nia is limited by only transient efficacy combined with its

high cost in the face of a low risk of life-threatening bleeding

in patients with autoimmune idiopathic thrombocytopenia.

It is appropriate for use in patients with serious bleeding

with this disorder as a temporizing measure while other ther-

apies are being administered. Anti-D antibodies (Rh

o

D

immune globulin) also may be useful in the management of

immune-mediated thrombocytopenia in patients who are

Rh-positive, presumably by a similar mechanism (antibody-

coated red blood cells block macrophage receptors). IVIG

has not been proven to be useful in treatment of thrombocy-

topenia owing to platelet alloimmunization.

Alloimmunization to platelet-specific antigen or HLA

antigens is a common sequela of repeated platelet transfu-

sions and limits the response to subsequent platelet transfu-

sions. For patients requiring long-term platelet support,

prevention of alloimmunization is desirable in order to pre-

serve the efficacy of transfusion therapy. Methods to mini-

mize platelet alloimmunization include reducing the total

number of all blood product transfusions, adhering to strict

criteria for transfusing platelets, removing the source of the

HLA sensitization (ie, white blood cells) before transfusion

of any blood product (by filtration or irradiation), and using

HLA-identical donors.

The optimal management of several conditions associ-

ated with thrombocytopenia is under active study. Treatment

of these conditions should be undertaken in consultation

with a hematologist to ensure accurate diagnosis and up-to-

date treatment.

APPROACH TO THE BLEEDING PATIENT

When approaching a patient with a suspected bleeding disor-

der, it is important to assess quickly the prior personal and fam-

ily history of bleeding, the pattern of bleeding, and the pattern

of laboratory abnormalities. If the personal or family history is

suggestive of an inherited bleeding disorder, the apparent

inheritance pattern, bleeding manifestations, and laboratory

abnormalities should suggest the most likely diagnoses. If the

personal and family histories are negative, defective hemostasis

is most likely acquired, although some of the milder inherited

disorders of hemostasis may not be manifested until significant

trauma or surgery occurs later in life. The pattern of bleeding

may suggest the nature of the hemostatic defect (Table 17–10),

and the pattern of laboratory abnormalities (Table 17–11) will

help to localize defects in the hemostatic system.

CURRENT CONTROVERSIES & UNRESOLVED

ISSUES

Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage

For more than a century, critically ill patients have been

observed to have a high rate of GI hemorrhage. Preventive

strategies emerged to decrease this complication, including

CHAPTER 17

428

the use of antacids, histamine-2(H2) receptor blockade, pro-

ton pump inhibitors (PPIs), and mucosal protective agents.

However, trials of these therapeutics have yielded conflict-

ing results, with some studies showing a benefit in selected

high-risk patients (eg, patients with mechanical ventila-

tion, hemostatic defects, or prior GI hemorrhage), others

showing an increase in hospital-acquired pneumonia and

complications related to drug interactions, and others

demonstrating no difference in any clinical outcome. Until

this issue is resolved, preventive therapy with mucosal protec-

tant agents (eg, sucralfate), H

2

blockade, or PPIs can be con-

sidered for patients identified to be at high risk for bleeding.

Underlying hemostatic defects should be treated according to

the general principles discussed earlier. The use of nons-

teroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and low-dose

aspirin increases the risk of GI bleeding independent of their

effects on platelet function. When Helicobacter pylori–associ-

ated ulcer is identified, long-term treatment with omeprazole

or eradication with antibiotics can decrease the risk of recur-

rent bleeding associated with aspirin or NSAIDs.

Gastroesophageal variceal hemorrhage is the most serious

form of GI hemorrhage, with 30% mortality observed with

first episodes. Varices occur in the setting of severe liver disease

so that—in addition to mechanical problems—coagulation

abnormalities, quantitative and qualitative platelet defects, and

excessive fibrinolysis contribute to bleeding. Management of

acute variceal bleeding requires GI specialists who can diag-

nose and treat varices endoscopically (eg, ligation, sclerosis,

or balloon tamponade) but also includes medical therapy

with vasoactive agents such as beta-blockers, nitrates, vaso-

pressin, and somatostatin analogues (eg, octreotide and

vapreotide). When these approaches fail, transjugular or sur-

gical shunting may be required to control bleeding.

Perioperative Bleeding

Preoperative evaluation of hemostasis should include

medical history with attention to adequacy of hemostasis—

spontaneous bleeding or bruising or unexpected bleeding

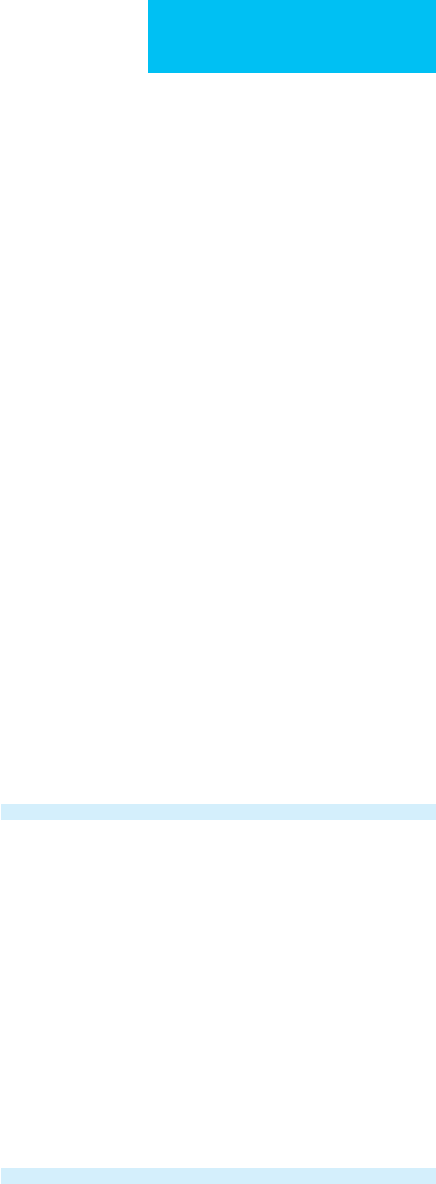

Pattern of Bleeding Possible Disorders

Ecchymoses and mucosal

bleeding; petechiae

Thrombocytopenia or platelet

dysfunction

von Willebrand disease

Severe coagulopathies

Spontaneous hemarthroses, soft

tissue hematomas

Hemophilia A and B, other severe

coagulopathies

Posttraumatic or surgical bleeding Thrombocytopenia or platelet

dysfunction

von Willebrand disease

Coagulopathies

Impaired vascular integrity

Inadequate surgical hemostasis

Massive injuries

Generalized oozing from mucosal,

venipuncture, surgical sites

Consumptive coagulopathies, DIC

Excessive fibrinolyis

Severe thrombocytopenia or

platelet dysfunction

Table 17–10. Approach to the bleeding patient by pat-

tern of bleeding.

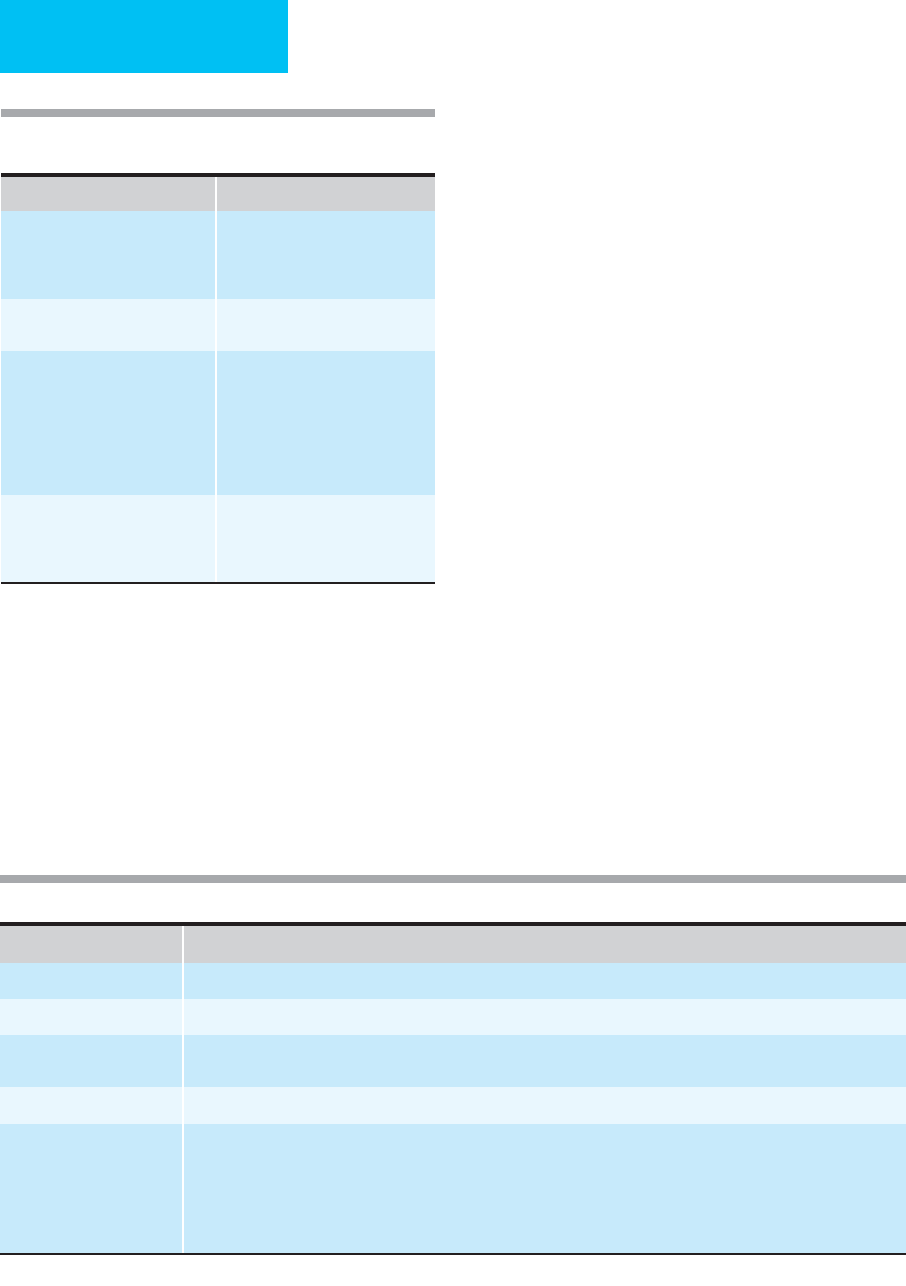

Table 17–11. Approach to the bleeding patient by pattern of screening laboratory abnormalities.

Abnormal Test Possible Defects

PT only Factor VII deficiency (inherited, vitamin K deficiency, warfarin effect) or inhibitor

aPTT only

∗

Factor XII, HMW kininogen, prekallikrein, XI, IX, or VIII deficiency or inhibitors to these factors; lupus anticoagulant

PT and aPTT Deficiency or inhibitor of factor X, V, II (prothrombin), fibrinogen

Multiple factor deficiencies (liver disease, DIC, consumptive coagulopathies, vitamin K deficiency, high dose warfarin effect)

Bleeding time prolonged Platelet dysfunction or thrombocytopenia, improper technique

All screening tests normal Other coagulation abnormalities:

Factor XIII deficiency

Excessive fibrinolyis

Paraproteinemia

Vascular defect (including inadequate surgical hemostasis)

Supporting tissue abnormality

∗

Deficiencies of factor XII, HMW kininogen, prekallikrein, and lupus-type inhibitors prolong the aPTT but do not cause bleeding.

BLEEDING & HEMOSTASIS

429

after dental extractions or prior surgical procedures suggests

the presence of an underlying hemostatic defect. Medical ill-

nesses such as liver or renal disease, myeloproliferative disor-

ders, and paraproteinemias predispose patients to excessive

postoperative bleeding. In the absence of symptoms of a

bleeding disorder or such medical illnesses, the value of rou-

tine laboratory screening has been questioned. Most postop-

erative bleeding results from surgical or technical problems

and not from hemostatic defects. The PT and aPTT are not

sensitive enough to detect mild defects and, when abnormal

in a patient with no previous bleeding history, may not accu-

rately predict the risk of bleeding. Whether any laboratory

screening should be done depends also on the type of

planned procedure (ie, minor versus major, use of cardiopul-

monary bypass, neurosurgical procedures, etc.). Table 17–12

outlines suggested laboratory screening prior to surgery. If

abnormalities in screening tests are detected, further evalua-

tion should be done to define the precise abnormality.

Intraoperative hemostasis with ligature, cautery, and top-

ical thrombogenic substances (eg, fibrin glue or topical

bovine thrombin) is essential to prevent postoperative bleed-

ing. In the postoperative period, excessive bleeding may be

due to a hemostatic defect that was not detected by the

screening tests. Mild coagulation factor deficiencies may not

prolong the aPTT, particularly if other factors are elevated

(eg, factor VIII increases in acute inflammatory states and

may mask mild deficiency of other factors). Preoperative use

of aspirin or other antiplatelet drugs may increase postoper-

ative bleeding; if bleeding is severe and the bleeding time is

prolonged, desmopressin or platelet transfusions may be

required for control of bleeding. Surgery on the prostate

gland or uterus may be associated with localized hyperfibri-

nolysis with excessive bleeding. Antifibrinolytic therapy with

aminocaproic acid can be considered for control of bleeding

(5-g loading dose followed by 1 g/h intravenously or orally

until bleeding has stopped), although there is some risk of

thrombi developing in the ureters (following prostate surgery)

that are resistant to lysis. Acute DIC may occur for many rea-

sons following surgery, or decompensation of previously

compensated DIC may develop as a result of tissue factor

release during surgery (Table 17–13).

Acute renal failure owing to hypotension, massive blood

loss, or medications can result in platelet dysfunction, which is

exacerbated by anemia. Posttransfusion purpura with throm-

bocytopenia may occur in previously sensitized individuals.

The use of intraoperative bovine thrombin as a hemostatic

agent may precipitate the development of antibodies to throm-

bin and factor V. There does not appear to be any significance

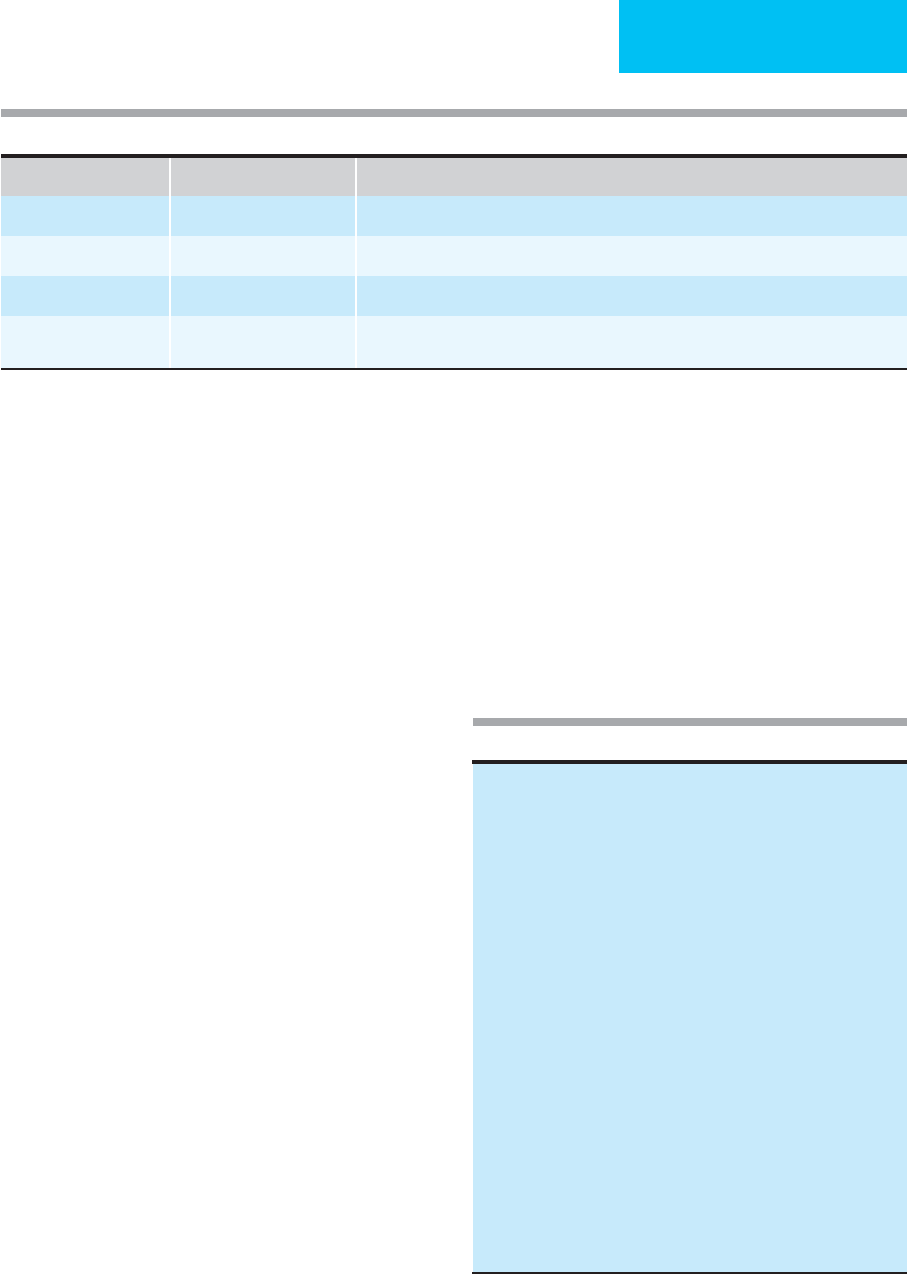

Bleeding History Type of Surgery Recommended Laboratory Tests

No suggestive history Minor (dental, skin biopsy) None

No suggestive history Major Platelet count, aPTT

Possible bleeding history Major, bypass pump PT, aPTT, platelet count, bleeding time; if normal, factor XIII assay, euglobulin clot lysis time

Positive bleeding history Minor or major Same as above; if negative: thrombin time, factor assays for VIII, IX, XI, alpha

2

-antiplasmin

assay, post-aspirin bleeding time

Table 17–12. Preoperative laboratory screening.

Sepsis

Hypotension

Acute hepatic necrosis

Release of bone marrow thromboplastins

Liver injury (drugs, hypotension, blunt or penetrating trauma)

Tissue factor release during surgery

Peritoneovenous shunting

Use of cell saver device with excessive suction

Release of tissue factor from placenta

Abruptio placentae

Amniotic fluid embolism

Septic abortion

Placenta previa

Retained dead fetus

Trauma

Fat embolism

Brain injury

Extensive soft tissue injury

Burns

Decompensation of chronic (compensated) DIC

Dissecting aortic aneurysm

Kasabach-Merritt syndrome

Cancer

Infusion of activated clotting factors

Prothrombin complex concentrates

Recombinant activated factor VII

Table 17–13. Causes of postoperative DIC.

CHAPTER 17

430

to the antithrombin inhibitor; however, factor V inhibitors

may cause bleeding. Factor VIII inhibitors also may develop

postoperatively; the mechanism for this has not been defined.

Hetastarch, a plasma volume expander, may cause persistent

coagulation abnormalities, particularly in elderly patients,

those with preexisting hemostatic defects, or with prolonged

use. If bleeding is severe, plasmapheresis to remove these large

molecules may be required to control bleeding.

When postoperative bleeding is encountered, immediate

evaluation with history (to uncover preexisting risks and med-

ication use) and laboratory testing (ie, PT, aPTT, and platelet

count) should be done. Medical treatment of hemostatic

defects will depend on the specific abnormalities identified. If

history and screening laboratory tests are unrevealing, consid-

eration should be given to reexploration of the surgical site to

identify adequacy of surgical hemostasis.

Perioperative management of patients with inherited

bleeding disorders requires preoperative collaboration

among the surgeon, anesthesiologist, hematologist, and

blood bank to ensure that optimal hemostasis is achieved

during and after surgery. The details of therapy will depend

on the nature of the specific disorder, the type of surgical

procedure, and whether any additional medical complica-

tions are present.

Posttraumatic Bleeding

In the setting of massive trauma, multiple pathophysiologic

processes contribute to severe bleeding, including multiple

vascular defects, massive transfusion with dilution of coagu-

lation factors and platelets, DIC with acceleration of fibrinol-

ysis, and hypotension. The presence of coagulopathy

following trauma increases the risk of mortality. Severe coag-

ulation disturbances associated with trauma may result in

adrenal hemorrhage, which can further exacerbate hypoten-

sion. Certain types of injuries are particularly associated with

DIC: fat embolism, brain injury, extensive soft tissue injury,

and extensive burns. Pelvic ring fractures are associated with

massive blood loss, often hidden owing to tracking of bleed-

ing up into the retroperitoneal space. Control of bleeding in

such circumstances may be difficult, even with aggressive

blood product support—with fresh-frozen plasma, platelets,

red blood cells, and cryoprecipitate. rFVIIa has been used to

treat massive hemorrhage in trauma patients with some suc-

cess, but evidence supporting its use is primarily anecdotal.

Further studies are necessary to determine which patients are

most likely to benefit from rFVIIa and at what dose it should

be administered.

REFERENCES

Bakhtiari K et al: Prospective validation of the International Society

of Thrombosis and Haemostasis scoring system for disseminated

intravascular coagulation. Crit Care Med 2004;32:2416–21.

[PMID: 15599145]

Caldwell SH, Chang C, Macik BG: Recombinant activated factor VII

(rFVIIa) as a hemostatic agent in liver disease: A break from con-

vention in need of controlled trials. Hepatology 2004;39:592–8.

[PMID: 14999675]

Finazzi G, Harrison C: Essential thrombocythemia. Semin Hematol

2005;42:230–8. [PMID: 16210036]

Hedner U: Recombinant factor VIIa: Its background, development

and clinical use. Curr Opin Hematol 2007;14:225–9. [PMID:

17414211]

Kamal AH et al: How to interpret and pursue an abnormal pro-

thrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time, and

bleeding time in adults. Mayo Clin Proc 2007;82:864–73. [PMID:

17605969]

Kantorova I et al: Stress ulcer prophylaxis in critically ill patients: A

randomized, controlled trial. Hepatogastroenterology

2004;51:757–61. [PMID: 15143910]

Levi M, de Jonge E, van der Poll T: Plasma and plasma components

in the management of disseminated intravascular coagulation.

Best Pract Res Clin Haematol 2006;19:127–42. [PMID:

16377546]

Levi M, de Jonge E, van der Poll T: New treatment strategies for dis-

seminated intravascular coagulation based on current under-

standing of the pathophysiology. Ann Med 2004;36:41–9.

[PMID: 15000346]

MacLeod JB et al: Early coagulopathy predicts mortality in trauma.

J Trauma 2003;55:39–44. [PMID: 12855879]

Mannucci PM, Duga S, Peyvandi F: Recessively inherited coagula-

tion disorders. Blood 2004;104:1243–52. [PMID: 15138162]

O’Connell KA et al: Thromboembolic adverse events after use of

recombinant human coagulation factor VIIa. JAMA

2006;295:293–8. [PMID: 16418464]

Roberts HR, Monroe DM 3rd, Hoffman M: Safety profile of recom-

binant factor VIIa. Semin Hematol 2004;41:101–8S. [PMID:

14872430]

Rodeghiero F, Tosetto A, Castaman G: How to estimate bleeding

risk in mild bleeding disorders. J Thromb Haemost

2007;5:157–66. [PMID: 17635722]

Rodeghiero F, Castaman G: Treatment of von Willebrand disease.

Semin Hematol 2005;42:29–35. [PMID: 15662613]

Spirt MJ: Stress-related mucosal disease: Risk factors and prophy-

lactic therapy. Clin Ther 2004;26:197–213. [PMID: 15038943]

Stein DM, Dutton RP: Uses of recombinant factor VIIa in trauma.

Curr Opin Crit Care 2004;10:520–8. [PMID: 15616396]

Tarantino MD, Aledort LM: Advances in clotting factor treatment

for congenital hemorrhagic disorders. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol

2004;2:363–8. [PMID: 16163206]

431

18

Psychiatric Problems

Stuart J. Eisendrath, MD

John R. Chamberlain, MD

ICUs provide the most advanced technology available to

patients with the most serious medical and surgical illnesses.

Perhaps as a consequence, these facilities are often associated

with some of the most stressful psychiatric conditions within

the hospital. Indeed, some physicians have jokingly referred

to the ICU as the “intensive scare unit.” These conditions in

ICUs may affect both patient and staff. This chapter will

describe some of the significant problems.

Most patients entering the ICU will attempt to manage

the stress of their stay with their characteristic coping mech-

anisms. Some regression generally occurs, however, as most

patients experience stressors such as fear of death, enforced

dependency, and potential permanent loss of function.

Separation from family and the loss of autonomy that

accompanies medical treatment in the ICU frequently lead to

further psychologic regression. They may try to cope with

stress by suppressing their feelings, using humor to laugh at

stressful aspects of their situation, or trying to anticipate a

return to good health. If these techniques fail, the individual

may turn to more primitive mechanisms such as projection,

passive-aggressive maneuvers, acting-out behavior, and gross

denial of illness. All this takes place during a time when the

patient must deal with serious and usually multiple medical

problems.

A number of clinical syndromes may develop as a result

of the stressors inherently associated with occupancy of a bed

in the ICU. This discussion will focus on several that may

adversely influence recovery. Delirium, the so-called ICU

psychosis, generally is not due to psychological stress alone

but develops in association with altered brain function.

Anxiety may occur at any time during the patient’s stay in the

ICU—entry, midpoint, or discharge. Depression also may

occur at any point during the patient’s stay but most often

occurs after the immediate threat to life has been dealt with

and the patient must contemplate the subacute prognosis

and ultimate outcome of the disease. Finally, we will discuss

how the ICU environment affects the staff working there.

Delirium

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Waxing and waning of consciousness.

Disorganized thinking.

Perceptual disturbances such as visual hallucinations.

Disorientation.

General Considerations

Early reports from ICUs gave rise to the diagnosis of an ICU

syndrome characterized essentially as a delirious state with

psychotic features such as hallucinations. It was believed to

be due to the stress an ill individual felt in a foreboding envi-

ronment with little privacy, lack of sleep, and sensory over-

load. Whether or not this syndrome actually existed as a

specific entity, current research indicates that delirium

occurring in the ICU is most likely due to factors similar to

those patients experience on general medical and surgical

wards—with the difference that ICU patients may have more

severe reactions because of their more severe illnesses.

Stress may play some role in producing delirium, but it is

typically only a contributing one. Other factors that alter

brain function are usually the primary etiologic agents. The

critical care physician should not automatically attribute

delirium to stress. Remembering that delirium is an organic

dysfunction of the CNS will facilitate the search for likely

causes and the provision of appropriate treatment. This

aggressive approach is justified given the serious impact of

delirium on morbidity and mortality in hospitalized

patients. Studies have shown that patients suffering an

episode of delirium have an increased risk of death, a longer

hospital stay, and a greater need for subsequent nursing

home placement. There are at least three broad hypotheses

Copyright © 2008 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. Click here for terms of use.

CHAPTER 18

432

relating to the production of delirium. Any one or any com-

bination of these factors may cause delirium in a particular

patient.

A. Increased Central Noradrenergic Production—Drug

or alcohol withdrawal states are the most common condition

producing delirium in the hospital and probably also the

most common condition responsible for increased nora-

drenergic discharge. Locus ceruleus–controlled production

of brain catecholamines is believed to play a central role in

this type of delirium.

B. Dopamine and Cholinergic Systems—Imbalance of

brain dopamine and cholinergic systems can be recognized

in central anticholinergic syndromes produced by atropinic

agents. These may produce a relative excess of dopaminergic

activity, giving rise to an agitated delirium. This hypothesis

also provides a framework for understanding how

dopamine-blocking agents such as haloperidol may act by

restoring the relative balance between dopaminergic and

cholinergic systems that is disturbed in delirium. Delirium-

producing agents such as the amphetamines, which cause a

shifting of the balance toward the dopaminergic side, also

can be better understood in this framework.

C. Toxic Causes of Delirium—A third framework for

understanding delirium involves the environment brain cells

operate in. Side effects of medications or endotoxins associ-

ated with bacterial infections can affect neuronal function-

ing. Similarly, conditions such as hyperthermia or hypoxia

can disturb functioning throughout the CNS. Many of the

preceding abnormalities are believed to affect the midbrain

particularly; this may, in turn, lead to fluctuations in the

reticular activating system with alterations in level of conscious-

ness and the ability to attend to stimuli in the environment—a

key feature of many cases of delirium.

D. Multifactorial Features—In the ICU there are typically

numerous factors that play a role in producing delirium. A

patient with asthma and pneumonia provides an example—

with fever and hypoxia as well as high levels of circulating

corticosteroids and catecholamines. Although single causes

should be sought diligently, it is unusual to be able to iden-

tify and correct just one causative factor of delirium.

Clinical Features

The clinical criteria for delirium in the ICU setting consists

of a number of signs and symptoms. Typically, the patient

has a waxing and waning of consciousness—may be somno-

lent at one moment and highly alert and agitated a short time

later. The patient’s ability to attend to external stimuli fluctu-

ates over time. Delirious patients usually have disorganized

thinking manifested by rambling or incoherent speech.

Patients frequently have perceptual disturbances such as mis-

perceptions of real objects (illusions) or frank hallucinations.

Patients usually have disorders in normal sleep-wake cycles and

altered psychomotor behavior (either agitation or retardation).

Patients also typically have disorientation to time, place, and

situation. Memory impairment, when present, is generally

global for both recent and remote events. Delirium usually

develops within hours to days. The presence of delirium sig-

nifies primarily organic brain dysfunction and is not a man-

ifestation of psychological distress alone.

The signs and symptoms listed in the preceding para-

graph are useful in making a clear-cut diagnosis.

Unfortunately for that purpose, however, many ICU patients

present only some of the criteria and may require ongoing

vigilance. Indeed, one of the keys to diagnosis in these

patients is repeated observations over time. The waxing and

waning of consciousness so common in delirious patients

requires serial monitoring because a patient may appear

quite lucid at one moment and quite confused a half hour

later. Nursing staff often have the best data on mental status

because of their continuing contact with the patients.

The physician should examine specifically for the presence

of delirium. This involves performing some type of specific

cognitive assessment such as the Folstein Mini Mental Status

Exam. However, intubated patients can be difficult to assess

with this instrument. Newer diagnostic instruments such as

the Cognitive Test for Delirium (CTD) can be very useful in

this setting. This instrument was developed for use in critical

care settings and reliably distinguishes patients with delirium,

dementia, and acute psychiatric illness. This type of examina-

tion tests the patient’s ability to attend to stimuli, concentrate

on a task, comply with simple memory requests, demonstrate

language capabilities through auditory comprehension, and

show orientation to time and situation. More important, this

type of test allows the examiner to detect cognitive deficits

that otherwise would go unrecognized. For example, psychi-

atric consultation may be sought for a patient who is poorly

compliant with the medical regimen. Many of these patients

prove to be suffering from delirium and have significant

memory deficits that make compliance impossible—they

cannot remember instructions for 30 seconds.

The patient may appear quietly confused and in a daze.

This type of delirium may be easily missed because the patient

presents no behavioral problem. Some delirious patients, on

the other hand, present behavioral problems ranging from

pulling out catheters and lines to biting or striking members of

the staff. These patients appear agitated, fearful, and restless.

They may be hallucinating and intensely involved in their psy-

chotic states. One physician described his state of mind during

his stay in the ICU as follows: “I saw a vulture flying over me.

I worried about any drop of blood spilling onto the sheets

because I knew that would bring the vulture down for the

attack.” This physician had been fearfully watching the ceiling

for several days but never told the doctors or nurses because

“they couldn’t do anything, and they’d think I was crazy.”

Many delirious patients resort to primitive psychological

coping mechanisms. They may exhibit massive denial of any

medical problem or externalize their problem as being the

fault of somebody else rather than of their illness. Delirious

patients often project anger about their helplessness onto

PSYCHIATRIC PROBLEMS

433

their caregivers. This gives rise to paranoid ideation about

caregivers trying to poison or otherwise harm them. Other

delirious patients—like the doctor in the preceding example—

experience hallucinations that are often threatening. These

hallucinations usually are visual and occur without any exter-

nal stimulus. Many patients will have visual illusions that

involve a misperception of actual external stimuli. For exam-

ple, one patient was convinced that the intravenous standard

in his room was actually a person poised to attack him.

Differential Diagnosis

In the critically ill patient—especially an intubated patient,

for whom communication is most difficult—delirium may

appear to be similar to other conditions.

A. Anxiety—Anxiety occurs quite frequently in the ICU. In

some instances, anxiety may occur in patients who have

delirium. Individuals with cognitive processing impairment

may be quite difficult to reassure. Thus many patients may be

anxious in the ICU, but only some will also have delirium—

although the majority of delirious patients will experience

anxiety and fear. Patients without delirium do not have the

significant cognitive impairment and deficits in reality test-

ing (such as hallucinations) so common in delirium.

B. Underlying Psychosis—ICU patients may have an

underlying psychosis (eg, schizophrenia) that can be confused

with delirium. Schizophrenic patients rarely have visual hal-

lucinations. Visual hallucinations usually are present owing to

an organic cause that requires investigation. Schizophrenic

patients who have paranoid delusions generally have well-

formed ones that are fixed over months and years. Delirious

patients, on the other hand, have rapidly developing delu-

sional beliefs that shift over hours to days. Most schizophrenic

patients have a history of psychiatric treatment and neurolep-

tic medications. Delirious patients generally do not have such

a history. Furthermore, schizophrenic patients typically have

onset of illness by the early to middle twenties, characterized

by a progressive decline in function. In contrast, delirium

often affects older patients and causes a precipitous decline in

mental status and functioning.

C. Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome—Schizophrenic

patients—or any patient who has received a neuroleptic

medication—are at risk for development of neuroleptic malig-

nant syndrome, characterized by altered mental status, auto-

nomic instability, and extrapyramidal symptoms that are often

severe (eg, lead-pipe rigidity). This syndrome can develop par-

ticularly with high-potency neuroleptic medications when

the individual also suffers from complicating conditions such

as fever and dehydration. Diagnosis in these patients is often

assisted by elevated creatine phosphokinase (CPK) levels,

myoglobinuria, and decreased serum iron levels.

D. Depression—The subdued, quiet delirious patient may be

mistaken for a depressed one. The depressed patient, however,

usually has the depressive view of the world associated with

that disorder along with symptoms such as a sense of worth-

lessness, guilt, and global pessimism. In some instances, small

test doses of dextroamphetamine (eg, 2.5 mg twice daily) may

allow the clinician to differentiate depressive and delirious

patients. The depressed patient may become less depressed

after medication, whereas the delirious patient usually

becomes more agitated. A past psychiatric history of depres-

sive disorder also may help to differentiate the disorders.

E. Personality Disorder—It is not unusual for staff to apply

the pejorative label personality disorder to a patient who fails

to comply with their requests. Whenever such a diagnosis is

contemplated, one should seek confirmation from family or

friends. Personality disorders represent longstanding pat-

terns of maladaptive behavior. They do not develop acutely,

although they may be exacerbated by the stress of illness.

They may emerge in patients after the immediate threat to

life has passed. Psychiatric consultation is often helpful in

confirming this diagnosis.

F. Dementia—One way of conceptualizing the difference

between dementia and delirium is by applying the analogy of

acute and chronic renal failure. Delirium represents acute

cerebral insufficiency, whereas dementia is typically a

chronic condition. Dementia syndromes may represent a

variety of conditions (eg, multi-infarct dementia or

Alzheimer’s disease) characterized by generalized diminu-

tion of intellectual functioning. Most dementias—except for

the subcortical ones, such as in Parkinson’s disease—show

some evidence of cortical dysfunction such as aphasia or

apraxia. Dementia syndromes develop over months or years

rather than hours or days. The patient’s family should be

consulted to clarify baseline mental functioning.

A key finding is that delirious patients typically have a

waxing and waning of consciousness and the ability to attend

to stimuli; deficits in demented patients generally are fixed

throughout the day until nightfall, when “sundowning” may

occur. It is quite common to see dementia patients who have

preserved remote memory, whereas in delirium, all forms of

memory may be impaired. It is unusual for dementia

patients to suffer hallucinations, whereas delirious patients

frequently have hallucinations.

Electroencephalograms may aid in the differentiation of

delirium and dementia. The former often show generalized

slowing, whereas the latter do not.

Treatment

A. Establish the Cause—The key to treatment of delirium

is identification of its cause or causes whenever possible.

Since delirium is usually an acute process, a vigorous investi-

gation of reversible causes should be undertaken, much as

one would investigate the cause of acute renal failure and

attempt to correct it as rapidly as possible. Delirium should

be regarded as an example of acute cerebral failure that is asso-

ciated with significantly increased morbidity and mortality.

There are studies in which patients with delirium had a

CHAPTER 18

434

markedly higher mortality rate than other patients (8% ver-

sus 1%; likelihood ratio = 2.3), a higher rate of admission,

and a higher rate of institutionalization. Hospital stays often

are prolonged by an average of 7 days in delirious patients.

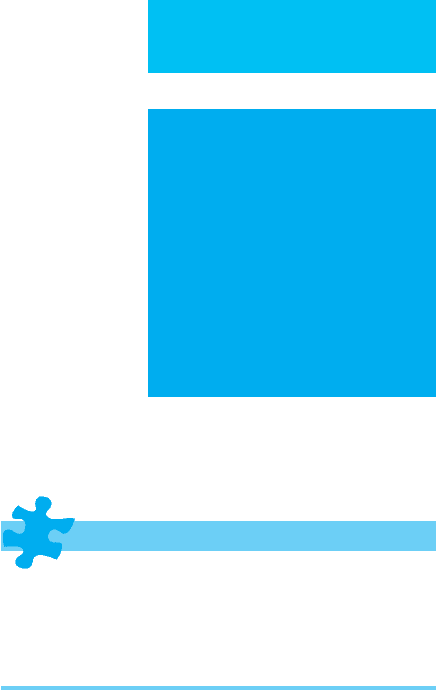

There are many causes of delirium. The most common

causes in the ICU are listed in Table 18–1. Withdrawal states

are among the most common causes of delirium in the gen-

eral hospital and always should be considered in assessing the

patient. In some instances, the patient may conceal or be

unable to provide information about drug or alcohol use.

Family and friends will be able to help to establish this his-

tory. In some instances, considerable probing may be neces-

sary. For example, one postoperative vascular surgery patient

denied the use of alcohol or drugs; persistent questioning,

however, revealed that she had increased her usual daily 0.5-mg

alprazolam dosage fourfold in the month prior to surgery

because of anxiety. When she entered the hospital, this med-

ication had been discontinued. Two days later, she had a

florid delirium that responded rapidly to alprazolam. The

benzodiazepines are the prototypical agents for the treat-

ment of alcohol and sedative withdrawal. They are safe in

large doses, prevent seizures, and are well tolerated. An

important feature for ICU use is that they are available in

oral, parenteral, and sublingual formulations.

Medications given in the ICU frequently can produce sig-

nificant psychoactive effects. Table 18–2 lists a number of

drugs that have been established as having these effects.

Switching medications certainly is one of the easiest changes

to make in trying to manage a delirious patient.

Other causes such as hypoxia and hypoperfusion need to be

reversed before improvement from delirium can occur.

Delirium may be the first sign of an infectious process and

should suggest that possibility when no other cause is discov-

ered. For example, a postoperative patient who develops delir-

ium without any identifiable cause may be suffering from a

wound abscess that only becomes apparent several days later.

B. Nonpharmacologic Management—Once one or more

causes are identified, the primary goal of treatment is to

reverse the disorder. In a significant number of cases of delir-

ium, no specific cause can be identified; in others, the identi-

fied cause cannot be reversed easily (eg, an asthmatic on

high-dose corticosteroids). In these instances, symptomatic

treatment may be required. Family may be enlisted to spend

time at the bedside to provide an orienting stimulus. Other

environmental measures may include providing a clock, cal-

endar, and soft music. Staff should attempt to provide ade-

quate day-night orientation and allow the patient to sleep at

night as much as possible. Four-hour periods that allow for

all stages of sleep may be the most beneficial.

C. Pharmacologic Management—For many patients with

delirium, the aforementioned measures will not be enough.

Medications become indicated when behavioral control is

necessary or when distress is severe. For example, a quietly

delirious patient suffering from frightening hallucinations is

a candidate for pharmacotherapy.

1. Management of withdrawal syndromes—A number

of principles must be considered in initiating therapy. If a

withdrawal state is present, the appropriate agent to cover the

withdrawal should be given as soon as possible. Sufficient

medication must be given to abort the withdrawal process

and keep it from reemerging. Alcohol withdrawal is the most

common of these conditions. A frequent mistake is to under-

dose with a benzodiazepine early in the withdrawal process

and then try to catch up with a full-blown delirium later.

Early substantial doses of long-acting agents such as

Drug or alcohol withdrawal or intoxication

Medication effects (eg, corticosteroids, cimetidine, lidocaine)

Hypoxia

Hypoperfusion

Infections (eg, systemic or central nervous system, HIV)

Structural lesions (eg, subdural hematomas)

Metabolic disorders (eg, electrolyte abnormalities, hypercalcemia,

hyperglycemia)

Ictal or postictal states

Postoperative states

Fat emboli

Dehydration

Sleep deprivation

Environmental stress

Pulmonary embolism

Table 18–1. Common causes of delirium in the ICU.

Acyclovir Fluoroquinolone antibiotics

Amiodarone Ganciclovir

Amphetamines Histamine H

2

blockers

Amphotericin B Interferon alfa

Anticonvulsants Isoniazid

Antidepressants Ketamine

Antihistamines Ketonazole

Atropine and other Levodopa

anticholinergics Lidocaine

Barbiturates Methylphenidate

Benzodiazepines Metoclopramide

Beta-adrenergic blockers Metronidazole

Cimetidine Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

Corticosteroids Opioids

Cycloserine Procaine derivatives

Cyclosporine Propafenone

Digitalis glycosides Quinidine

Dronabinol Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole

Epoetin alfa (erythropoietin)

Modified from: Drugs that cause psychiatric symptoms. Med Lett

Drugs Ther 1988;40:21–24.

Table 18–2. Drugs that may cause delirium in the ICU.

PSYCHIATRIC PROBLEMS

435

diazepam may provide timely control. However, lorazepam

may be preferred in patients with liver disease because its

metabolism (via glucuronide conjugation) is less affected in

such individuals.

2. Management of delirium of unknown cause—

a. Benzodiazepines—When the cause of delirium is not

known but withdrawal from sedatives or alcohol is suspected,

one might consider a pharmacologic probe by giving a ben-

zodiazepine such as 1–4 mg lorazepam. If the patient’s condi-

tion worsens, that essentially rules out alcohol and most

benzodiazepine withdrawals. A different course of pharma-

cotherapy then must be pursued. In addition, these agents are

preferred for the agitation present with anticholinergic over-

dose or when there is a need to raise the seizure threshold.

Relatively short-acting agents with no active metabolites, such

as lorazepam, are preferred for this application.

b. Haloperidol alone or with lorazepam—Haloperidol is

often administered intravenously even though the intravenous

form is not approved by the Food and Drug Administration

(FDA). Before initiating haloperidol, some cardiovascular con-

siderations must be addressed (discussed below). Initial dosage

depends on the age and size of the patient. A small elderly

woman may benefit from 0.2 to 0.5 mg haloperidol every

4 hours. A younger 70-kg man may start with 1–2 mg every

2 hours or even higher doses. A more agitated patient should

receive larger doses, and some studies have advocated an initial

infusion of 5–10 mg followed by a continuous infusion at a rate

of 5–10 mg/h. This medication has a mean distribution time of

11 minutes and a half-life of 14–17 hours. If the first dose fails

to produce significant improvement, the dose should be

repeated at 30-minute intervals to allow time for distribution

to occur. The second dose is usually twice the first dose. If

monotherapy fails to produce the desired effect, one may add

0.5–1 mg lorazepam. This combination has been found to

improve symptom control while decreasing the side effects of

treatment. If the patient remains agitated 30 minutes follow-

ing the addition of lorazepam, one may give doses of

haloperidol up to 5 mg and lorazepam 0.5–2 mg at 30-minute

intervals until control is established. In many instances, con-

trol of delirium can be achieved with 5–30 mg haloperidol

and 2–4 mg lorazepam. Some patients may require amounts

substantially above these levels. Doses up to 975 mg haloperi-

dol in a 24-hour period have been reported.

Once control is established, approximately half the first

24-hour total dosage can be given on the following day in

equally divided doses. Each subsequent day’s dosing is

reduced by half until further dosing is no longer necessary.

The goal, once symptom control is achieved, is to taper the

patient to the minimally required dose. Many cases of delir-

ium will clear within a few days, particularly when the cause

has been reversed.

When giving intravenous haloperidol, several points

need to be considered. Generally speaking, intravenous

haloperidol imposes a much lower risk of extrapyramidal

side effects than oral or intramuscular forms. The reason is

not completely clear. It may be that the intravenous route

allows brain receptors to bind with different forms of the drug.

It is possible also that most patients who receive intravenous

haloperidol have some form of central anticholinergic process

by virtue of their delirium that provides a protective effect

against extrapyramidal reactions. Nonetheless, when giving

haloperidol, the clinician should continue to monitor the

patient for adverse reactions, which include dystonias, akathisia,

and neuroleptic malignant syndrome.

The incidence of cardiovascular side effects from

haloperidol is very low. Haloperidol has been found to pro-

long the QT interval and has been linked with rare episodes

of torsade de pointes, ventricular fibrillation, and sudden

death. These effects generally seem to occur with high doses

of the medication and have led to recommendations for

establishing a baseline ECG and subsequent monitoring of

the QT interval. Additional recommendations are to monitor

serum magnesium and potassium. Most cases of hypoten-

sion with haloperidol have been in association with hypov-

olemia. Administering the medication in a slow infusion over

5–10 minutes may be helpful in preventing hypotension, so

intravenous pushes should be avoided.

c. Newer agents—Newer agents such as the atypical

antipsychotics (including risperidone, quetiapine, and olan-

zapine) are receiving increased attention in the treatment of

delirium. They have fewer neurologic side effects (eg,

extrapyramidal symptoms) than the typical antipsychotics

(eg, haloperidol), particularly in elderly and seriously med-

ically ill individuals who are most at risk for delirium. In one

prospective, double-blind trial, haloperidol and risperidone

were equally efficacious in the treatment of delirious

patients. In a small open-label trial, low doses of risperidone

(average maintenance dose of 0.75 mg/day) improved cogni-

tive and behavioral symptoms of delirium. Olanzapine was

compared with haloperidol in a randomized, prospective

trial. While both groups demonstrated similar clinical

improvement and a lessened need for benzodiazepine seda-

tion, 6 of 45 patients treated with haloperidol were found to

have extrapyramidal symptoms, whereas no patients treated

with olanzapine developed extrapyramidal or other side

effects. Quetiapine has been found, in small studies, to be

effective for the treatment of delirium and well tolerated

when used at low doses. One drawback to atypical neurolep-

tic use is that only olanzapine and ziprasidone are currently

available in immediate-release parenteral formulations.

d. Other pharmacologic interventions—When the combi-

nation of haloperidol (or another antipsychotic) and

lorazepam fails to achieve control, additional interventions

may be necessary, including sedation (with opioids, propo-

fol, barbiturates, or benzodiazepines), pharmacologic paral-

ysis, and mechanical ventilation. These measures, however,

do not enhance the patient’s sense of control, and if sedation

is inadequate, they can be quite terrifying to the patient.

A newer agent for sedation and analgesia in the critical

care patient is dexmedetomidine, an α

2

-agonist. Reported

advantages of this medication are minimal interference with

CHAPTER 18

436

respiration and the ability for patients to be aroused easily. It

is currently approved for infusions up to 24 hours in adults.

D. Social and Psychologic Management—A key consider-

ation in managing delirium involves the psychological

aspects. The patient’s family often has major concerns about

the prognosis for mental recovery. The physician should

reassure both the family and the patient that the condition is

usually reversible and that return to baseline mental func-

tioning can be expected. Empathically telling the patient that

the physician understands the confusion the patient feels

may convey a real sense of hope. Encouraging the patient to

report any strange phenomena such as hallucinations may

make the patient feel more at ease. Similarly, informing the

family that accusations and delusional ideas brought forth

during an episode of delirium have no real meaning is obvi-

ously useful.

Current Controversies and Unresolved Issues

Delirium is such a heterogeneous entity that many issues

remain to be delineated by prospective studies. Molecular

mechanisms for delirium and the role of neurotransmitters

need to be established. We still do not know what the optimal

medications are for controlling delirium, the maximum daily

dosage of haloperidol and other agents, and whether patients

really benefit from large doses of medications or if the prac-

tice helps the staff more than the patient. The use of atypical

antipsychotic medications in the elderly also requires further

study because the available information suggests that use of

at least some of these agents in elderly patients with demen-

tia may be associated with an increased risk of cerebrovascu-

lar adverse events. Other questions relate to possible

preventive measures, whether psychological factors alone can

cause delirium in the absence of organic factors, and a possi-

ble final common pathway for all cases of delirium.

Depression

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Depressed mood.

Feelings of worthlessness and inappropriate guilt.

Negative thinking.

Recurrent thoughts or wishes for death or suicide.

General Considerations

Depression occurs in 20–42% of the medically ill. Any

patient with a medical illness severe enough to require

admission to the ICU faces a number of psychological issues,

including real and potential losses. For example, the patient

with myocardial infarction must deal with the threat to life as

well as the potential loss of future health and normal function.

These losses are enough to produce depressive symptoms in

many patients and sad feelings in most patients. An individual

undergoing major surgery must deal with the loss of bodily

integrity and the threat of death. These actual and potential

losses may produce a sense of helplessness in many patients.

Patients are usually placed in unfamiliar surroundings

with little sense of autonomy. These conditions may generate

a depressive view of the world. Cognitive distortions can

develop so that the individual begins to make mistakes in

judgment such as forecasting catastrophe or interpreting

innocuous events negatively. Patients may begin to think of

themselves as worthless and feel they are a burden to family

and friends. Motivation to participate in medical care may be

impaired. In an interesting study, healthy volunteers were

admitted to an ICU to investigate the psychological changes

associated with that environment. Subjects developed

decreased vigor as well as increased confusion and fatigue

that were attributed solely to the ICU environment. The sub-

jects also were found to engage in introspection and to have

a negative view of the hospital environment. In another

study of patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft-

ing, those with longer stays in the ICU were at risk for greater

levels of depressive symptoms postoperatively.

This depressive picture is often associated with biologic

changes. Neurotransmitter levels and receptor function

change significantly. Serotonin and noradrenergic systems

have substantial alterations. Endocrine dysfunction in both

the pituitary-adrenal and thyroid axes may become dis-

turbed. Even immune function may be altered.

Clinical Features

Patients in the ICU who have clinically significant depression

can by assessed by general criteria for depression. These cri-

teria, however, have only limited usefulness in the ICU

patient because of the context. For example, neurovegetative

symptoms are of limited value; many ICU patients have

appetite and sleep disturbances, but that does not mean they

are depressed.

Nonetheless, some signs and symptoms of depression in

ICU patients can be used to make a diagnosis of depression.

The presence of a depressed or lowered mood is a hallmark.

Irritability, particularly when out of character for an individ-

ual, is another marker of depression. Diminished interest in

activities such as interacting with family or viewing televi-

sion often indicates depression. Pronounced thoughts about

death or wishes for it in the form of suicidal ideation also

indicate depression.

Additional criteria can be used in assessing a patient for

depression. One group of factors involves the depressive view

of the world a depressed patient develops. For example, see-

ing oneself, one’s doctor, and one’s future in negative terms

correlates positively with a diagnosis of depression. Feelings

of guilt, worthlessness, and hopelessness are also common in

depression. Feeling helpless means the individual feels

unable to help himself or herself get better; feeling hopeless

means the individual does not believe anyone else can help