Bongard Frederic , Darryl Sue. Diagnosis and Treatment Critical Care

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

SURGICAL INFECTIONS

407

and sepsis. Suppurative thrombophlebitis and type 2

necrotizing fasciitis are generally monomicrobial. For the

most part, antibiotic treatment is important but secondary

to aggressive surgical debridement.

Cellulitis is an infection of soft tissues that retain their

blood supply and viability. There is edema and erythema, but

appropriate antibiotic therapy will resolve the infection in

most cases. Abscesses and fasciitis are associated with loss of

blood supply, tissue necrosis, and collections of bacteria,

leukocytes, and cellular debris. Surrounding tissues contain

an abscess, whereas fasciitis involves and spreads along facial

planes. Necrotizing fasciitis is a virulent process frequently

associated with septic shock and carries a high mortality.

Diabetic foot infections can present anywhere along this

range from cellulitis to fasciitis, with associated dry or wet

gangrene. Limited infection often responds to antibiotics,

but surgical debridement or amputation is required in the

face of abscesses, wet gangrene, osteomyelitis, or fasciitis.

These infections are associated with the neuropathy and vas-

culopathy of diabetes. In these patients, a distinction should

be made between macrovascular and microvascular disease.

Peripheral pulse assessment and documentation of ankle-

arm indices are essential to the evaluation of these patients,

although the latter can be inaccurate if the arteries are calci-

fied and noncompressible. At any rate, stenoses and occlu-

sions of named arteries may be amenable to percutaneous

and/or surgical amelioration, allowing salvage of tissue and

resolution of infection. Presence of wet gangrene, radi-

ographic evidence of soft tissue emphysema or osteomyelitis,

and signs of sepsis influence urgency of surgical manage-

ment of these infections. Surgeons must strike a balance

between being too radical with tissue resection and avoiding

serial operations that only postpone amputation.

Ultrasound and CT scanning define the character and

extent of soft tissue abscesses. Most abscesses will not resolve

with antimicrobial therapy alone; a combined approach with

image-guided or surgical drainage is usually required. It can

be difficult to distinguish between cellulitis and abscess on

the one hand and life-threatening necrotizing fasciitis on the

other. Classic “hard signs” of fasciitis include skin necrosis

and bulla formation, palpable crepitance and soft tissue gas

on radiography, and hypotension. However, some or all of

these may be absent. Pain out of proportion to clinical find-

ings is also an important clue to the diagnosis. CT scanning,

with its greater sensitivity than plain films, is currently used

widely to help with the diagnosis of these difficult cases.

When available, frozen-section analysis of a musculofascial

biopsy obtained at bedside under local anesthesia can estab-

lish the diagnosis in difficult cases.

There are two major categories of necrotizing fasciitis.

Type 1 is polymicrobial with involvement of at least one

anaerobic species such as C. perfringens. Facultative anaer-

obes from the Enterobacteriaceae family and nontypable

streptococci generally are involved as well. A subclass of type 1

necrotizing fasciitis is Fournier’s gangrene. This fulminate

infection involves the skin and soft tissues of the scrotum,

perineum, and penis. It spreads along the fascial planes and

can involve the thighs and wall of the torso. The majority of

patients with Fournier’s have diabetes mellitus. Type 2 is

monomicrobial, most commonly owing to group A β-hemolytic

streptococci (ie, GAS or Streptococcus pyogenes), the so-called

flesh-eating bacteria. Increasingly, community-acquired

MRSA is producing necrotizing fasciitis, including the pedi-

atric population. Antecedent varicella infection is a risk fac-

tor in about half these patients.

Necrotizing fasciitis has a mortality ranging from

20–60% in developed countries. Risk of death is elevated in

association with immunosuppression, IVDA, streptococcal

toxic shock syndrome, advanced patient age, and presence of

significant comorbidities. Delays in medical and surgical

therapy are deleterious to patient survival. Initial antibiotic

therapy includes high-dose intravenous penicillin, semisynthetic

β-lactam antibiotics, and clindamycin. The latter should

cover most strains of community-acquired MRSA, but van-

comycin should be considered pending final culture and sen-

sitivity results. Whether the fasciitis is type 1 or type 2 cannot

be determined confidently at the outset. Hemodynamically

unstable patients require early, aggressive crystalloid replace-

ment of intravascular volume. In general, central venous

pressure monitoring guides this volume resuscitation and

directs rational addition and titration of vasoactive medica-

tions such as norepinephrine and vasopressin.

The mainstay of treatment for necrotizing fasciitis is

prompt radical debridement of all involved skin, subcuta-

neous tissue, muscle, and fascia. Defining the limits of this

resection is difficult and requires experience, but insufficient

initial debridement can compromise patient survival.

Immediate amputation, even hip disarticulation, may be neces-

sary to effect survival in advanced cases. It is important, when

possible, to have a compassionate but frank discussion with the

patient and family as to the possible extent of surgery before

embarking on an operation for necrotizing fasciitis. General

comprehension of this illness’s severity should not be assumed.

Just as in ANM and necrotizing pancreatitis discussed earlier,

the need for multiple operations should be anticipated.

Adjunctive measures such as hyperbaric oxygen therapy and

intravenous immunoglobulin administration have been

advised for treatment of necrotizing fasciitis, but their use has

not been rigorously verified in controlled studies.

An uncommon but similarly life-threatening infection

seen in burn and other surgical ICUs is suppurative throm-

bophlebitis. Inflammatory superficial thrombophlebitis

occurs quite often after placement of peripheral vein

catheters. Fortunately, its infectious counterpart is unusual. It

should be suspected, though, in the febrile ICU patient whose

site of infection is elusive. All former sites of intravenous

access should be examined carefully for induration, erythema,

tenderness, centrally projecting red streaks, and purulent

drainage. The latter cinches the diagnosis, whereas the other

signs may indicate vein exploration under local anesthesia.

CHAPTER 16

408

If the vein is infected, it must be excised urgently in a distal-

to-proximal direction, stopping only when normal, patent

vein is encountered or all infected vein clearly has been

removed. On occasion, infection extends from peripheral

veins into central ones, and thoracotomy with central vein

resection may be a necessary lifesaving measure.

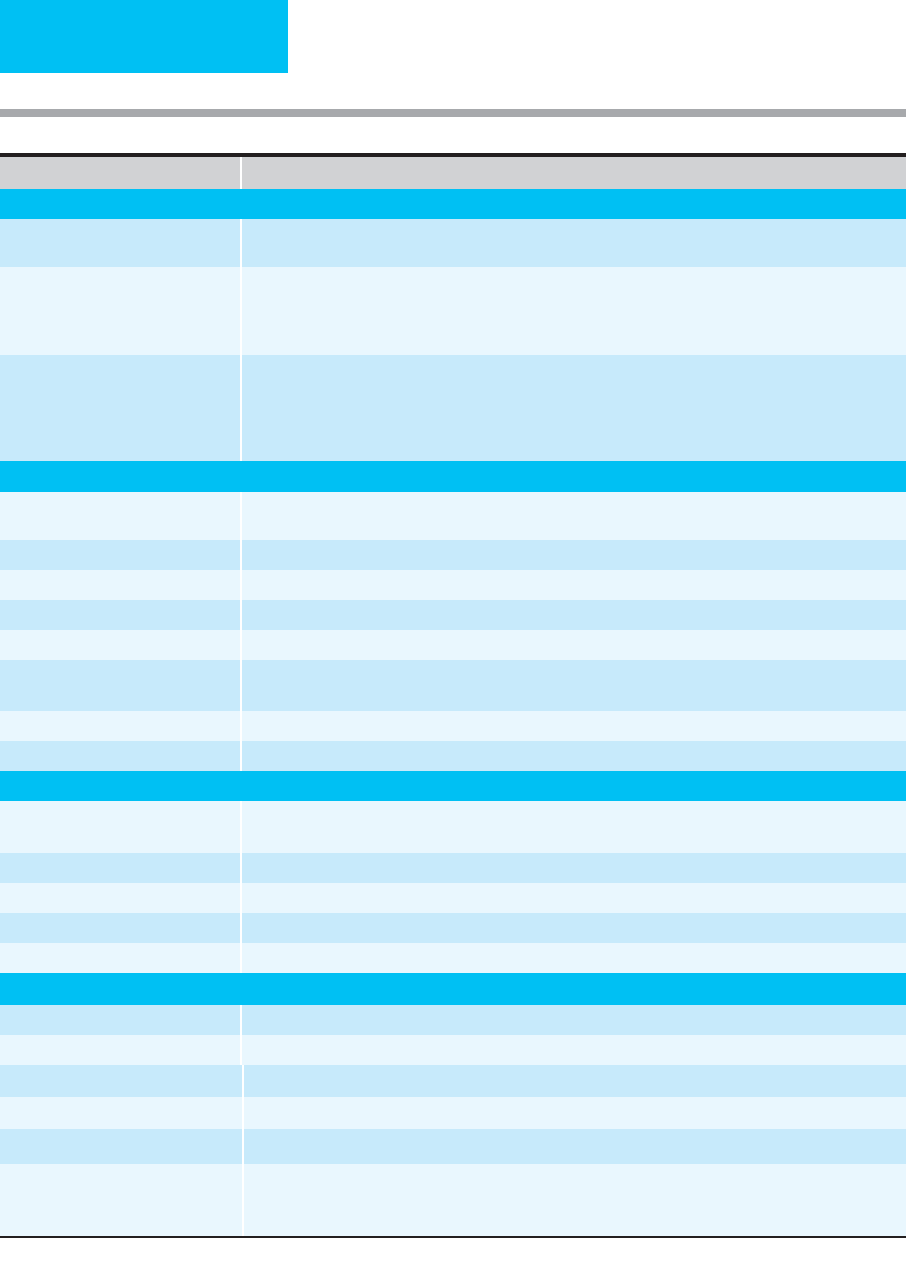

Treatment of soft tissue infections is summarized in

Table 16-4.

Golger A et al: Mortality in patients with necrotizing fasciitis. Plast

Reconstr Surg 2007;119:1803–7. [PMID: 17440360]

Rieger UM et al: Prognostic factors in necrotizing fasciitis and

myositis: Analysis of 16 consecutive cases at a single institution

in Switzerland. Ann Plast Surg 2007;58:523–30.

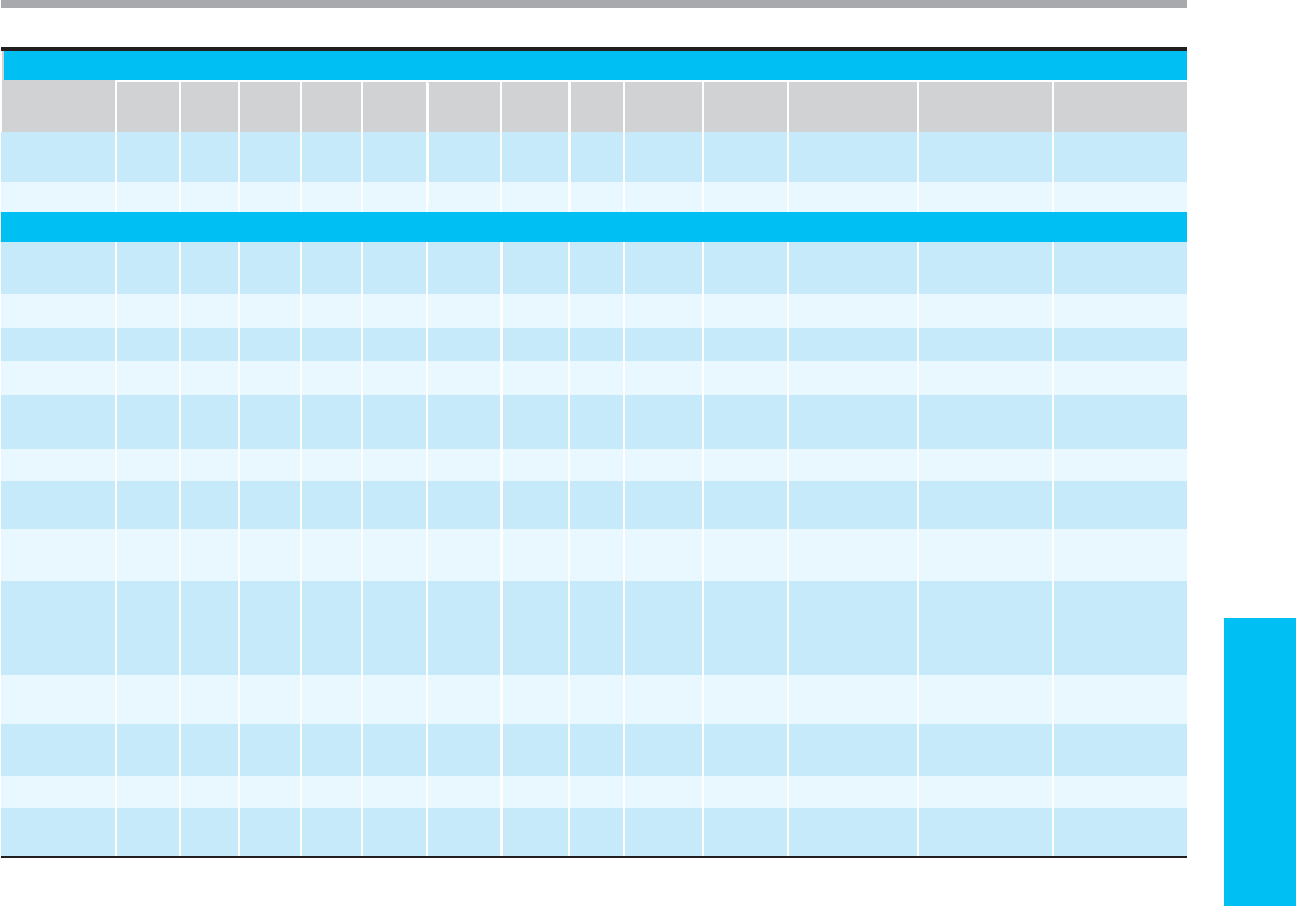

Table 16–4. Summary of soft tissue infections in adult surgical patients.

Diagnosis Organisms Initial Antibiotics Adjunctive Therapy

Diabetic foot infection

S. aureus

(assume MRSA), group

A strep

(S. pyogenes),

group B

strep

(S. agalactiae),

coliforms,

anaerobes

Vancomycin 1 g IV q12h + β-lactam with

β-lactamase inhibitor

or

carbapenem IV

Surgical debridement,

vascular surgical evaluation as

indicated

Cellulitis and soft tissue abscess

S. pyogenes,

group B, C, and G

strep,

S. aureus,

Enterobacteriaceae

Penicillin G 1–2 million units IV q6h

or

nafcillin-oxacillin 2 g IV q4h; vancomycin

1 g IV q12h for facial cellulitis; for

diabetics, linezolid 600 mg IV q12h

or

vancomycin 1 g IV q12h + carbapenem

IV

Consider necrotizing fasciitis

Type 1 necrotizing fasciitis Aerobes, anaerobes including

Clostridium sp.

Penicillin G 24 million units/24 h in

divided IV doses q4–6h + clindamycin

900 mg IV q8h + vancomycin 1 g IV

q12h + ceftriaxone 2 g IV q24h

Goal-directed therapy for

sepsis, prompt and aggressive

surgical debridement

Type 2 necrotizing fasciitis

S. pyogenes

(GAS),

S. aureus

(community-acquired MRSA)

Penicillin G 24 million units/24 h in

divided IV doses q4–6h + clindamycin

900 mg IV q8h

Goal-directed therapy for

sepsis, prompt and aggressive

surgical debridement

Suppurative thrombophlebitis

S. aureus, S. pyogenes,

Enterobacteriaceae

Vancomycin 1 g IV q12h (MRSA),

nafcillin-oxacillin 2 g IV q4h (MSSA),

carbapenem IV

or

extended-spectrum

penicillin (Enterobacteriaceae)

Removal of intravascular

device, excision of entire

involved vein

Data from Gilbert DN et al (eds): The Sanford Guide to Antimicrobial Therapy, 37th ed. Sperryville, VA: Antimicrobial Therapy, Inc., 2007.

409

17

Bleeding & Hemostasis

Elizabeth D. Simmons, MD

Bleeding is a common problem in critically ill patients in the

ICU. A rational approach to diagnosis and treatment of

bleeding requires an understanding of the major elements

of the hemostatic system, currently available laboratory tests

of hemostatic function, and specific disorders of hemostasis.

Bleeding disorders generally are categorized into defects of

coagulation and fibrinolysis, defects of platelets, and defects

of vascular integrity, but critically ill patients who are bleed-

ing may have defects in multiple arms of the hemostatic sys-

tem. Furthermore, defective hemostasis may result in

thrombosis as well as bleeding.

Normal Hemostasis and Laboratory Evaluation

A. Normal Hemostasis—The major elements of hemostasis

are outlined in Table 17–1. A complex interaction of vascular

endothelium, platelets, red blood cells, coagulation factors,

naturally occurring anticoagulants, and fibrinolytic enzymes

results in formation of blood clot at the site of vascular

injury and activation of repair mechanisms to promote heal-

ing of the injured blood vessel. Vascular injury results in

platelet adhesion and aggregation, activation of coagulation

factors ultimately resulting in cleavage of fibrinogen to fib-

rin, and formation of a stable blood clot consisting of cross-

linked fibrin polymers, platelets, and red blood cells.

Simultaneously, naturally occurring anticoagulants and fib-

rinolytic enzymes are activated, a process that limits the

amount of clot formed and degrades clot once the vessel is

repaired. The latter aspects of hemostasis serve to confine

clot formation to the site of vascular injury while permitting

continued blood flow through the affected blood vessel. The

precise factors that regulate the balance between clot forma-

tion and breakdown are not fully understood.

B. Laboratory Tests of Hemostasis (See Table 17–2)—

There are several generally available laboratory tests for eval-

uation of the function of the hemostatic system. Currently

available screening laboratory tests detect clinically signifi-

cant defects (quantitative and qualitative) of most but not all

of the important elements of hemostasis. The history should

dictate the choice of tests to determine the adequacy of hemo-

static function. A highly suggestive history for a bleeding dis-

order calls for sophisticated or specialized laboratory testing,

whereas abnormal test results may not be predictive of future

risk of bleeding in the absence of a significant bleeding history.

1. Tests of coagulation—Calcium and phospholipid are

required for normal coagulation to occur. In the laboratory,

measurement of coagulation times (eg, prothrombin time

and partial thromboplastin time) involves mixing decalcified

plasma (collected in citrate) and a phospholipid substitute

(thromboplastin), adding calcium, and determining the time

for visible clot formation using an automated system.

Different phospholipid reagents activate different parts of

the coagulation cascade, and an activating agent is added for

performance of the activated partial thromboplastin time

(aPTT). Prothrombin time (PT) generally is reported as the

international normalized ratio (INR), which compares

observed results against a reference thromboplastin to mini-

mize interlaboratory variability owing to differing sensitivi-

ties of thromboplastin reagents. The thrombin time (TT) is

performed by adding excess thrombin to decalcified plasma

(phospholipid is not required).

Standard coagulation times are not prolonged until factor

activities drop to less than 20–50% of normal (depending on

the specific factor deficiency). Therefore, a mixture of patient

plasma with normal plasma in equal quantities (1:1 dilution)

should normalize a prolonged coagulation time if due solely

to one or more factor deficiencies. Failure of a prolonged

coagulation time to correct after 1:1 dilution with normal

plasma implies the presence of a circulating inhibitor of

coagulation, including heparin. Detection of some factor

inhibitors may require incubation of the mixture prior to

performing the assay.

In vitro assessment of coagulation depends on the action

of factor XII, high-molecular-weight kininogen, and

prekallikrein (the contact factors), whereas in vivo hemostasis

Copyright © 2008 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. Click here for terms of use.

CHAPTER 17

410

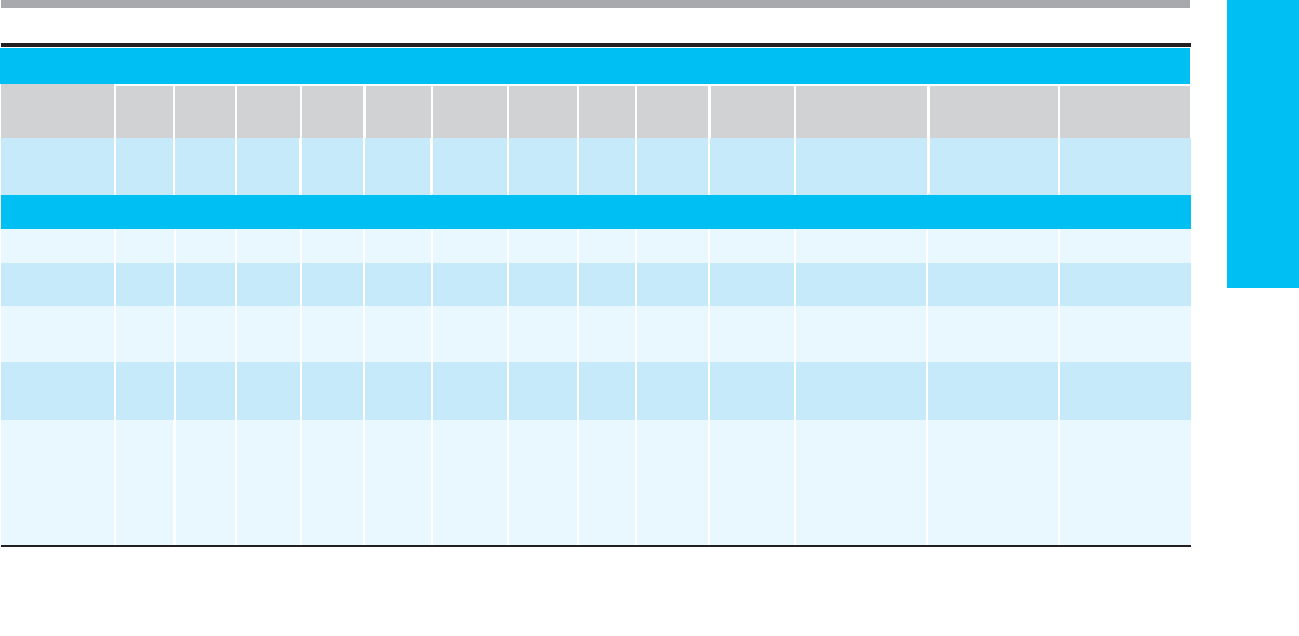

Element Participation in Hemostasis

Endothelium

Procoagulant Release of von Willebrand factor (vWF), factor VIII, tissue factor, plasminogen activator inhibitor, and platelet

activating factor in response to injury; maintains tight interendothelial junctions to prevent blood extravasation.

Anticoagulant Negative charge repels platelets and coagulation factors; produces prostacyclin; releases tissue plasminogen

activator in response to vessel injury; provides thrombomodulin for thrombin-mediated activation of protein

C; provides heparin-like molecules which interact with antithrombin III and accelerate its inactivation of

thrombin and other serine proteases.

Platelets Adhere to exposed subendothelium via vWF and aggregate in response to activation (via fibrinogen-glycoprotein

IIb/IIIa interaction); secrete agonists which stimulate further platelet aggregation; provide phospholipid for produc-

tion of thromboxane A

2

and for coagulation reactions; provide surface on which coagulation reactions are local-

ized; secrete coagulation factors (V, vWF), which increase local concentration; provide contractile machinery for

clot retraction; perhaps maintain interendothelial tight junctions by secretion of metabolically active substances.

Coagulation factors

Proenzymes In response to vascular injury, sequential activation (VII, IX, X, II) results in generation of thrombin and cleav-

age of fibrinogen to fibrin.

Thrombin In addition to cleavage of fibrinogen, activates platelets, factors V, VIII, and XIII, and protein C.

Fibrinogen Cleaved by thrombin to fibrin, which polymerizes to insoluble fibrin clot.

Factor XIII After activation by thrombin, cross-links fibrin polymers to stabilize clot.

Cofactors Factors V and VIII, both activated by thrombin, act as cofactors for X and IX, respectively.

Tissue factor Integral membrane constituent of vascular endothelial cells and stimulated monocytes; acts as receptor for

factor VII; initiates blood coagulation.

Calcium, phospholipid Necessary for several steps in coagulation.

Contact factors Factor XII, HMW kininogen, and prekallikrein are important for in vitro hemostasis only.

Anticoagulants

∗

Protein C Vitamin K-dependent anticoagulant, inactivates factors V and VIII after activation by thrombin bound to throm-

bomodulin on endothelial surfaces.

Protein S Vitamin K-dependent cofactor for protein C.

Thrombomodulin Receptor for thrombin, initiates activation of protein C pathway.

Antithrombin (AT) Inactivates thrombin and other serine proteases of the coagulation cascade.

Tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI) Inhibits tissue factor/factor VIIa complex.

Fibrinolytic system

Tissue plasminogen activator Cleaves fibrin-bound plasminogen to plasmin.

Urokinase Plasminogen activator found in urine and in plasma when fibrinolysis is stimulated.

Table 17–1. Normal hemostasis.

Plasminogen Once activated to plasmin, lyses fibrin and fibrinogen.

Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) Prevents activation of plasminogen by tissue plasminogen activator.

Alpha

2

-antiplasmin Inactivates circulating plasmin and prevents lysis of fibrin and fibrinogen.

Blood elements and rheology Laminar flow prevents contact of cellular elements with endothelium; free flow prevents accumulation of factors

at uninjured sites and dilutes concentration of activated factors; dislodges platelet plugs if not firmly attached to

subendothelium; provides inhibitory plasma proteins other than antithrombin to inactivated coagulation factors.

∗

Precise physiologic role in hemostasis not well defined: Other serine proteinase inhibitors (Serpin): alpha

2

-macroglobulin, alpha

1

-proteinase

inhibitor, C1 esterase inhibitor, protein C inhibitor, heparin cofactor II.

BLEEDING & HEMOSTASIS

411

appears to occur normally even with complete deficiency of

any of these proteins. Factor XI likewise is essential for in

vitro coagulation, but factor XI deficiency generally is associ-

ated with a very mild bleeding tendency. Specific coagulation

factor deficiencies can be identified using known deficient

plasma in a modification of the 1:1 dilution test when clini-

cally indicated.

Standard screening coagulation tests (ie, PT, aPTT, and

TT) do not detect mild coagulation factor deficiencies, factor

XIII deficiency, defects in fibrinolysis, or abnormalities of

platelets, blood vessels, or supporting connective tissue.

They are not useful for determining deficiencies of the nat-

urally occurring anticoagulants or for evaluating patients

with thrombotic disorders (except for patients with lupus

Test (normal range) Significance of Abnormal Test

Coagulation

Prothrombin time (PT)

(10–13 seconds) expressed as the

international normalized ratio (INR) (1.0)

Deficiencies of or inhibitors to extrinsic and common pathway factors: VII, X, V (<50%), II (<30%),

fibrinogen (<100 mg/dL).

Activated partial thromboplastin time

(aPTT) (25–40 seconds)

Deficiencies of or inhibitors of contact factors, intrinsic and common pathway factors: XII, HMW kininogen,

prekallikrein, XI (<50%), VIII, IX (<20%), X, V, II (<30–50%), fibrinogen (<100 mg/dL). Decreased value

may indicate increased concentration of factor (especially VIII) or hypercoagulable condition.

Thrombin time (TT) (10 seconds) Deficiency or defect of fibrinogen, inhibitors of thrombin action (heparin), or inhibitors of fibrin polymer-

ization (FDP, myeloma proteins).

Reptilase time Deficiency or defect of fibrinogen. Similar to thrombin time but unaffected by heparin.

Stypven time (Russell viper

venom time)

Differentiate factor X from factor VII deficiency (abnormal in factor X deficiency).

Dilute Russell viper venom time Detect lupus anticoagulant; affected by heparin.

1:1 dilution test (corrects to normal) Failure to correct consistent with inhibitors to specific factors or to phospholipid; heparin effect.

Correction to normal consistent with factor deficiency (some inhibitors may require incubation).

Factors assays (60% to >100%) Deficiencies of one or more coagulation factors.

5 M urea clot stability Deficiency of factor XIII.

Platelets

Platelet count (150,000–400,000/μL) Quantitative abnormalities of platelets.

Bleeding time (3–10 minutes) Impaired platelet function, thrombocytopenia, severe anemia, improper technique.

Aggregation (qualitative) Impaired platelet aggregation in response to platelet agonists; can localize defect based on pattern of

abnormal aggregation.

Ristocetin cofactor assay Decreased quantity or function of vWF in patient plasma.

Fibrinolysis

Fibrin(ogen) degradation products

(FDP) (<10 μg/mL)

Accelerated fibrinolysis.

Fibrinogen (150–400 mg/dL) Deficiency of fibrinogen.

Euglobulin lysis time (>2 hours) Accelerated fibrinolysis.

Protamine sulfate test Positive test indicates presence of circulating fibrin monomers.

D-dimer test Positive test indicates presence of cross-linked FDP, formed only if activation of factor XIII has resulted in

cross-linkage of fibrin polymers. Elevated in DIC, fibrinolysis, deep vein thrombosis, and pulmonary

embolism.

Table 17–2. Tests of hemostatic function (average normal values given).

CHAPTER 17

412

anticoagulants and contact factor deficiencies). Coagulation

times shorter than normal occur frequently, particularly if

there are higher than normal levels of any of the factors

measured by the test (especially factor VIII), which may

mask deficiencies of other factors.

2. Platelets—The platelet count can be determined by

automated cell counter or by estimation on a peripheral

blood smear (normal, 10–20 platelets/high-power field

[hpf]). The bleeding time is an in vivo test of platelet func-

tion. Bleeding time is affected by platelet number, platelet

function, position and depth of the incision, maintenance of

constant pressure above the site of the incision, medications,

hemoglobin concentration, and renal function. In thrombo-

cytopenic patients, the bleeding time varies as a function of

the cause as well as the degree of thrombocytopenia.

Although the bleeding time is useful in diagnosis of disor-

ders of platelet function, it may not be reliable as a predictor

of clinical bleeding. Other tests of platelet function include

in vitro platelet aggregation in response to various agonists

(eg, thrombin, epinephrine, adenosine diphosphate, and ris-

tocetin) for evaluation of patients suspected of having sig-

nificant disorders of platelet function rather than number.

3. Fibrinolysis—Elevated fibrin and fibrinogen degrada-

tion products and decreased fibrinogen concentration may

reflect excessive intravascular fibrinolysis, but these measure-

ments are not specific. The protamine sulfate test and the D-

dimer test may be useful to confirm the presence of

disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) as the cause of

elevated fibrin degradation products. The euglobulin lysis

time, which measures the action of plasminogen activators

and plasmin in blood, may be useful for confirming the pres-

ence of excessive fibrinolysis. Specific assays for elements of

the fibrinolytic system are available if clinically indicated.

Inherited Coagulation Disorders

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Personal and family history of bleeding disorder.

Abnormal screening coagulation tests.

Abnormal specific factor assays.

General Considerations

Inherited coagulation disorders result from a decrease in

quantity or function of a single coagulation factor, although

there are some cases of familial multiple coagulation factor

deficiencies. The inheritance pattern may be autosomal or X-

linked, dominant or recessive, or may be the result of a new

mutation, so a negative family history does not preclude the

presence of an inherited disorder of coagulation. A personal

history of bleeding may be absent if the defect is mild or if

there has been no prior challenge to the hemostatic system

(eg, major surgery or trauma). In addition, some coagulation

defects are variable over time, with fluctuations both in

bleeding manifestations and in laboratory abnormalities.

Nevertheless, most of the inherited disorders of blood coag-

ulation result in a typical clinical bleeding history accompa-

nied by characteristic reproducible laboratory abnormalities

(Table 17–3).

von Willebrand disease (vWD) is the most common inher-

ited bleeding defect in humans, but prevalence figures vary

widely because of variable expression and penetrance of the

genetic abnormality. The disease results from inheritance of

an autosomal dominant (rarely, autosomal recessive) decrease

in the quantity or function of von Willebrand factor (vWF).

vWF is essential in platelet adhesion and serves as a carrier for

the procoagulant factor VIII protein. Clinical manifestations

typically reflect impaired platelet function, with epistaxis,

easy bruising, menorrhagia, and excessive bleeding after sur-

gery, trauma, or dental procedures. Severe deficiencies (<1%

activity) are rare and may result in bleeding similar to that

seen in hemophilia A. vWD is heterogeneous in severity and

is subject to variability over time and within families. During

pregnancy, vWF levels increase, often sufficiently to permit

adequate hemostasis at childbirth.

Hemophilia A, which accounts for 80% of all hemophil-

ias, results from inheritance of an X-linked recessive muta-

tion in the factor VIII gene, giving rise to severe (<1%

activity), moderate (1–5% activity), or mild (>5% activity)

factor VIII deficiency. The incidence of hemophilia A is

approximately 1 in 5000 men. Hemophilia A does occur in

women, owing either to early X chromosome inactivation of

the normal X in a heterozygous female or to inheritance of

two abnormal X chromosomes (one from an affected father

and one from a carrier mother).

Clinical manifestations depend on the severity of the

deficiency (70% of patients have severe deficiency) but typi-

cally include lifelong spontaneous hemarthroses and soft tis-

sue hematomas, hematuria, and if severe, increased epistaxis,

gum bleeding, and ecchymoses. Postoperative or dental

bleeding is severe and prolonged. CNS hemorrhage occurs in

about 3% of patients and may be fatal. The severity of the

deficiency is generally constant within a family and over time

in an individual, but it varies between families.

Hemophilia B results from inheritance of an X-linked

recessive mutation in the factor IX gene. The pathophysiology

and clinical manifestations are virtually identical with those

of hemophilia A, although severe deficiency is present in only

50%. Hemophilia B is much less common than hemophilia A,

with an estimated incidence of 1 in 50,000 men.

Inherited deficiencies of all the other coagulation factors

have been reported (see Table 17–3), but these are rare. All are

autosomally inherited, usually recessive, and often result from

consanguineous parentage. Clinical severity correlates with

the degree of factor deficiency but is typically milder and

more variable than in hemophilias A and B. Combined defi-

ciencies of multiple coagulation factors are rare. Deficiencies

of factor XII, prekallikrein, and high-molecular-weight

kininogen cause prolongation of the aPTT but are not asso-

ciated with excessive bleeding or thrombosis.

BLEEDING & HEMOSTASIS

413

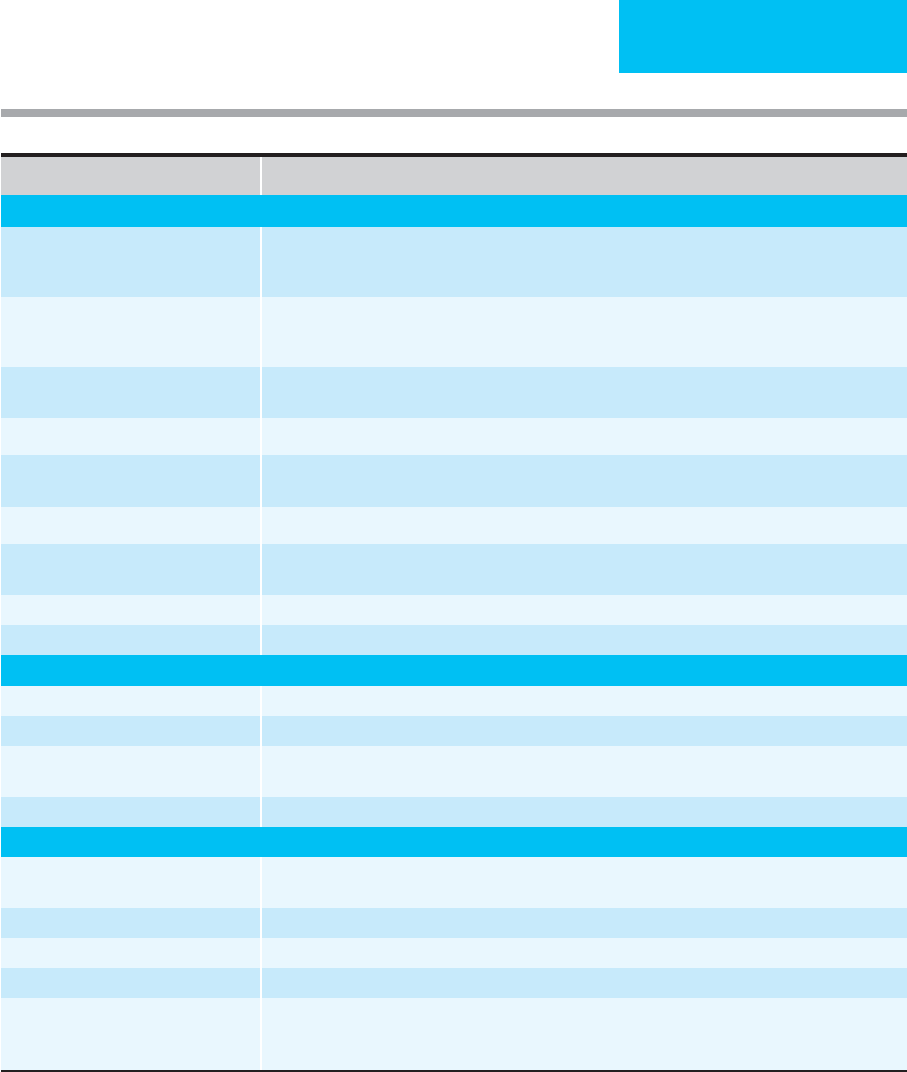

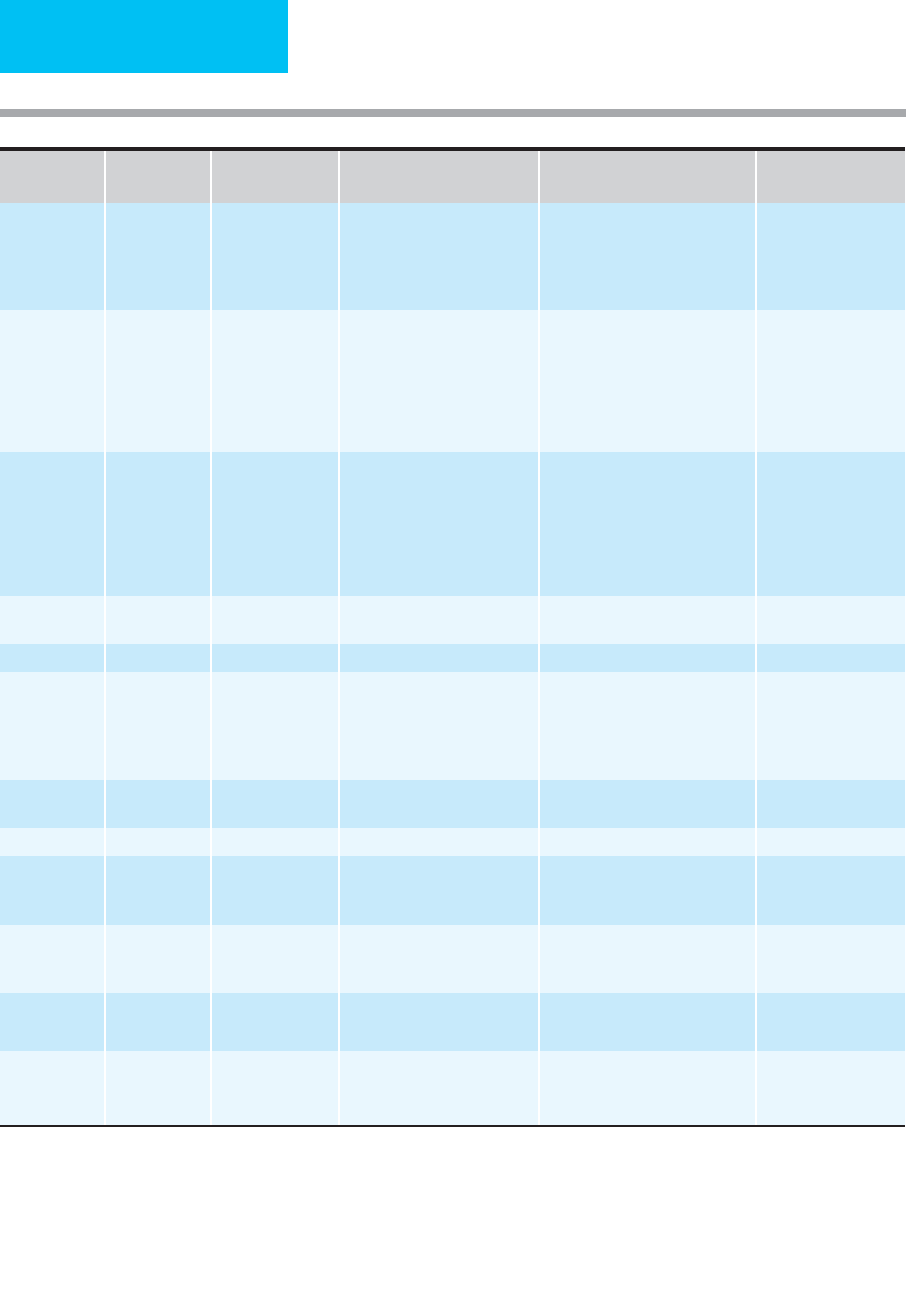

Table 17–3. Clinical manifestations of inherited coagulation factor deficiencies.

(

continued

)

Factor Deficiency

vWF VIII IX II V VII X XI XIII Fibrinogen

Dysfibrinogenemia

Combined Factor

V/VIII deficiency

Multiple Vitamin K-

dependent factors

Inheritance AD/AID/

AR

XR XR AR AR AR AIR AR AR AR AD AR AR

Incidence 1:100 1/10 K 1/40 K Rare Rare Rare Rare Rare

∗

Rare Rare Rare Rare Rare

Clinical manifestations

Severity

(most cases)

Mild 70%

severe

50%

severe

Mild Mild,

variable

Moderate,

variable

Moderate Mild Severe Mild Mild Moderate to severe Variable, not well-

described

Easy bruising + (+) (+) (+) + + + (+) + +

Epistaxis + (+) (+) (+) + + + (+) + + + +

Menorrhagia + (+) + + + (+) + + + +

Soft tissue

hematomas

+ + (+) (+) + + (+) + (+) +

Hemarthrosis • + + (+) (+) + + + (+) + +

Intracranial

hemorrhage

+ + • + + + + •

Gastrointestinal

hemorrhage

+ + (+) + + + (+)

Bleeding with

trauma, surgery,

or dental

procedures

+ + + + + (+) (+) (+) + • (+) + +

Umbilical stump

bleeding

• • + + • (+)

Spontaneous

abortions

+ + + +

Male infertility +

Poor wound

healing

(+) (+) + +

CHAPTER 17

414

∗

Factor XI deficiency much more common in Ashkenazic Jews (5–11% heterozygous).

†

Specific factor assays are available for the diagnosis of all the inherited factor deficiencies.

Key: Inheritance: AD, autosomal dominant; AR, autosomal recessive, XR, X-linked recessive; AIR, autosomal incompletely recessive; AID, autosomal incompletely dominant

Frequency of clinical manifestations: + common; (+) occasional; • rare

Thromboembolic

complications

+ + (with rx)

Laboratory abnormalities

PT prolonged + + + + + + + +

aPTT prolonged + + + + (+) + + + + + +

Thrombin time

prolonged

+ +

Bleeding time

prolonged

+ (+) (+) (+)

Other laboratory

tests

†

Risto-

cetin

cofactor,

factor

VIII

assay

Stypven

time

Stypven

time

5 M urea Reptilase time,

euglobulin lysis,

fibrinogen immuno-

electrophoresis

Low protein C/S

Table 17–3. Clinical manifestations of inherited coagulation factor deficiencies. (continued)

Factor Deficiency

vWF VIII IX II V VII X XI XIII

Fibrinogen

Dysfibrinogenemia

Combined Factor

V/VIII deficiency

Multiple Vitamin K-

dependent factors

BLEEDING & HEMOSTASIS

415

Clinical Features

A. Symptoms and Signs—Bleeding may occur sponta-

neously, but patients sometimes will give a history of bleed-

ing only after surgery, trauma, or dental extractions. In those

with vWD, platelet function is affected, so easy bruising and

menorrhagia may be prominent complaints. On the other

hand, patients with hemophilia often have spontaneous

hemarthroses, soft tissue hematomas, and hematuria. Physical

findings may reflect recent bleeding or may show evidence of

chronic bleeding such as decreased range of joint motion.

B. History—A detailed personal and family history of bleed-

ing often will uncover the nature of the coagulation disorder

and suggest its inheritance pattern. A family history of con-

sanguinity is pertinent for the rare autosomal recessive disor-

ders, and Ashkenazic Jewish ancestry may suggest the

possibility of factor XI deficiency.

C. Laboratory Findings—Laboratory abnormalities may

suggest an underlying hereditary bleeding disorder, but it is

important to remember that not all prolonged coagulation

tests indicate a bleeding diathesis, and some inherited bleed-

ing disorders are associated with normal coagulation tests.

There may be variability over time in some disorders, such as

vWD. The extent of laboratory evaluation for an inherited

coagulation disorder should be determined by the clinical his-

tory. Table 17–3 outlines the typical laboratory features of the

inherited coagulation disorders. Functional assays for factors

II, V, VII, VIII, IX, X, XI, and XII using known deficient

plasma in a modification of the 1:1 dilution test confirm spe-

cific factor deficiencies. Clot stability in 5 M urea with and

without the addition of normal plasma is the screening test of

choice for diagnosis of factor XIII deficiency and can be con-

firmed with a specific factor assay. The diagnosis of vWD is

based on finding low vWF antigen, abnormal ristocetin cofac-

tor activity, and low factor VIII activity (usually <10%).

Quantitative deficiency of vWF can be differentiated from

qualitative defects by electrophoretic analysis of vWF multi-

mers. Determining the subtype of vWD by multimer analy-

sis is important for proper management of bleeding

episodes.

Differential Diagnosis

Bleeding associated with abnormal coagulation tests also

may result from acquired coagulation disturbances, includ-

ing liver disease, vitamin K deficiency, DIC, inhibitors of spe-

cific factors, or therapeutic anticoagulation. Abnormal

coagulation tests may result from a deficiency of one of the

contact factors or from the presence of antiphospholipid

antibodies (lupus anticoagulant), neither of which causes

bleeding but may be associated with thrombosis. Mild coag-

ulation factor deficiencies may be associated with normal

or minimally prolonged clotting times and may result in

bleeding only if major vascular injury occurs. Bleeding in the

presence of normal coagulation times suggests the presence

of an underlying vascular defect, abnormal supporting con-

nective tissue, thrombocytopenia or platelet dysfunction,

excessive fibrinolysis, or factor XIII deficiency. Acquired

inhibitors to coagulation factors may be found in patients

with inherited factor deficiencies as a consequence of

replacement therapy and may be suspected in those who do

not respond adequately to factor replacement. An inhibitor

of coagulation can be confirmed by performing a 1:1 dilu-

tion test with normal plasma (preincubation may be neces-

sary to demonstrate the inhibitor).

Treatment

Factor replacement is appropriate for patients with inherited

coagulation disorders who have active bleeding or who

require surgical or dental procedures. The activity level nec-

essary for adequate hemostasis varies for each factor and

with the type of bleeding or planned procedure. General

guidelines for factor replacement are outlined in Table 17–4.

Aspirin and intramuscular injections should be avoided.

Surgical procedures should be performed only in centers

with adequate blood bank, coagulation laboratory, and

hematology consultation services. Treatment strategies for

patients with inhibitors complicating factor deficiencies

include desmopressin (for minor bleeding), high-dose fac-

tor replacement, use of products that bypass the factor

inhibitor (eg, activated prothrombin complex concentrate

with factor VIII inhibitor bypassing activity, recombinant

factor VIIa, and porcine factor VIII), and techniques to

lower the titer of the inhibitor (eg, plasmapheresis, intra-

venous immune globulin, immunosuppression, and induc-

tion of immune tolerance).

Adjuncts to factor replacement include desmopressin

acetate, antifibrinolytic agents such as aminocaproic acid and

tranexamic acid, and topical hemostatic agents such as fibrin

glue and fibrillar collagen preparations applied directly to

local areas of mucosal bleeding, such as epistaxis.

Desmopressin by intravenous (0.3 μg/kg over 15–30 minutes)

or intranasal (1.5 mg/mL in each nostril) administration

increases circulating levels of vWF and factor VIII by 2 to 5

times baseline within 15–30 minutes by releasing these factors

from endothelial storage sites. Desmopressin is useful for

most patients with vWD and in patients with mild to moder-

ate hemophilia A. Repeated infusions within 1–2 days may be

less effective, however, limiting the usefulness of desmo-

pressin in patients requiring sustained increases in vWF, fac-

tor VIII, or both. On the other hand, use of desmopressin may

completely eliminate the need for blood products in mild

bleeding episodes or during minor dental or surgical proce-

dures and may decrease the amount of blood products

required for major bleeds or surgical procedures. A test dose

of desmopressin should be administered about 1 week before

a planned surgical procedure to determine if a patient with

vWD or hemophilia A is responsive. Severe hemophiliacs and

those with qualitative abnormalities of vWF are rarely respon-

sive to desmopressin. Some subtypes of vWD (eg, type 2B)

CHAPTER 17

416

Factor

Deficiency

t

1/2

Hemostatic

Level

1

Preferred Sources

2

Dose

Interval Between

Doses

vWF 12 hours 25–50%

a. Desmopressin

3

b. Humate-P

c. Cryoprecipitate

4

a. 0.3 μg/kg IV/30 minutes or

1.5 mg/mL nasal spray

b. 30 units/kg

a. 24–48 hours

b. 12 hours for 2 days,

then 24 hours

VIII 9–18 hours 25–30% a. Purified factor VIII

b. Recombinant factor VIII

c. Desmopressin

5

a. 10–15 units/kg (minor),

30–40 units/kg (major)

b. 10 units/kg (minor); 15–25

units/kg (moderate); 40–50

units/kg, then 20–25 units/kg

(major); 50 units/kg (surgery)

12 hours (6–12 hours

following major surgery)

IX 20–25 hours 15–30% a. Purified factor IX

b. Recombinant

factor IX

c. Purified prothrombin

complex concentrates (PCC )

a. 10–20 units/kg

b. 100 units/kg, then 7.5

units/kg/h

c. 20–30 units/kg, then 15

units/kg (minor); 40–60

units/kg, then 20–25 units/kg

(major bleeding or surgery)

24 hours

II 3 days 20–40% a. Plasma

b. Purified PCC

a. 15 mL/kg, then 5–10 mL/kg

b. 20 units/kg, then 10 units/kg

24 hours

V 36 hours 25–30% FFP, PCC 15–20 mL/kg, then 10 mL/kg 12–24 hours

VII 4–7 hours 15–20% a. Plasma

b. Purified PCC

c. Recombinant factor VII

d. Factor VII concentrate

a. 20 mL/kg, then 5 mL/kg

b. 30 units/kg, then 10–20

units/kg

c. 15–30 μg/kg

d. 30–40 units/kg

a/b. 4–6 hours

c/d. 12 hours

X 40 hours 10–20% a. Plasma

b. Purified PCC

a. 15–20 mL/kg, then 10 mL/kg

b. 20–30 units/kg

24 hours

XI 80 hours 10–20% Plasma 15–20 mL/kg, then 5 mg/kg 48 hours

XIII 9–12 days 3–5% a. Plasma

b. Cryoprecipitate

c. Factor XIII concentrate

a. 15–20 mL/kg

b. 1 bag/10 kg

c. 10–20 units/kg

20–30 days

Fibrinogen 3–4 days a. Plasma

b. Cryoprecipitate

c. Fibrinogen concentrate

a. 15–20 mL/kg

b. 1 bag/10 kg

c. 20–30 mg/kg

48 hours

Combined

factors V/VIII

36 hours (V)

9–18 (VIII)

25–30% a. Plasma

b. Desmopressin (as in VIII)

a. 15–20 mL/kg 12 hours

Multiple Vitamin

K-dependent

factors

Varies by factor

(II, VII, IX, X)

Varies by factor a. Plasma

b. PCC

c. Oral Vitamin K

a. 15–20 mL/kg

b. 10–30 units/kg

c. chronic, high dose

Monitor levels

1

Estimated level required for normal hemostasis. Higher levels required for major bleeding or surgery (factors VIII and IX: 100%, factor XIII: 25–50%).

2

Plasma, fresh frozen (FFP) or fresh (FP), may be used interchangeably except for replacement of factors V and VIII.

3

Desmopressin is thrombogenic; use with caution in older patients with vascular disease; may induce fibrinolysis, often used in combination

with antifibrinolytic agents. Must give a test dose to determine efficacy; not effective for vWD type 2b, platelet-type vWD.

4

Use only if factor concentrate is unavailable.

5

In mild hemophilia A, may reduce or eliminate need for factor VIII replacement for minor surgery, dental work, or acute bleeding episodes.

Same dose as in vWD.

Table 17–4. General principles of factor replacement for inherited coagulation disorders.