Bongard Frederic , Darryl Sue. Diagnosis and Treatment Critical Care

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

397

0016

Surgical Infections

Timothy L. Van Natta, MD

∗

General Considerations

Persistent fever in the postoperative patient is always con-

cerning. Potential causes include infection, atelectasis,

deep venous thrombosis, and drug reactions. The surgical

wound and urinary tract are common infections sites.

While management of these problems is relatively straight-

forward, diagnosis and treatment of other inflammatory

and infectious processes can be problematic. It is often dif-

ficult to differentiate between systemic inflammatory

response syndrome (SIRS) and sepsis. Documentation of a

discrete infection is required for diagnosis of the latter.

Infection types and sites not thought of are unlikely to be

identified. An organized diagnostic approach pays divi-

dends, particularly when based on analysis by body region

and through monitoring the presence and duration of

indwelling devices. Early diagnosis of infection portends

optimal outcomes, preempting sepsis and its attendant

complications—provided antimicrobial agents and adjunc-

tive measures are used rationally.

Sepsis may be the reason for ICU admission, or it may

complicate another critical illness. A surgical patient can

present anywhere along a spectrum from SIRS to sepsis to

severe sepsis (ie, sepsis associated with organ dysfunction)

to septic shock to multiple organ dysfunction syndrome

(MODS). A patient’s course often devolves along these

stages despite the physician’s best efforts. However,

prompt application of goal-directed therapy raises the

likelihood of course reversal before irrevocable organ

damage occurs.

Balk RA, Ely EW, Goyette RE: Sepsis Handbook, 2d ed. Nashville,

TN: Thomson Advanced Therapeutics Communications and

Vanderbilt School of Medicine, 2004.

Prevention of Surgical Infections in the ICU

Surgical infections can be prevented through proper use of

prophylactic antibiotics. To be effective, the appropriate antibi-

otic must be administered within 1 hour before the operation

so that tissue levels are high at incision time. Antibiotics with

24-hour dosing are attractive in this regard because no postop-

erative doses are necessary. Prophylactic antibiotics have no

value beyond the first 24 hours following surgery. Their contin-

ued use puts patients at risk for antibiotic-associated

Clostridium difficile colitis, infection by multidrug-resistant

bacteria (eg, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus,

vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus, and Acinetobacter species),

and fungal infections. No less important, this practice adversely

affects the bacterial ecology in the ICU. Continuing “prophy-

lactic” antibiotics for the duration of drain and chest tube pres-

ence cannot be condoned. Furthermore, antibiotics cannot

compensate for suboptimal surgical conduct.

Invasive procedures in the ICU require strict sterile tech-

nique. This demands that one don a cap, mask, sterile gloves

and gown; generously prepare the area with chlorhexidine;

and meticulously drape the field. Once percutaneous

catheters are in place, making connections and sampling

must be done fastidiously. Chlorhexidine-laden catheter-site

dressings are effective in preventing infections and should be

used routinely. Of course, clinical crises can demand expedi-

tious, nonsterile placement of intravenous and other

catheters. These should be removed as soon as feasible and

never beyond 24 hours from time of placement. When cen-

tral venous access is necessary but central pressure monitor-

ing is not, conversion from a central line to a percutaneously

inserted central catheter (PICC line) lessens infection risk.

When central access is no longer required, a change from

central to peripheral access should be accomplished as soon

as practical. Other devices, such as ventriculostomy drains,

chest tubes, epidural catheters, arterial lines, and urinary

catheters, should be removed as soon as their utility wanes.

The ICU team should take daily stock of all such devices and

think critically about the continued value of each.

∗

James A. Murray, MD, and Howard Belzeberg, MD, were the

authors of this chapter in the second edition.

Copyright © 2008 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. Click here for terms of use.

CHAPTER 16

398

Other preventive measures are noteworthy. It has been

established that postoperative hyperglycemia is directly asso-

ciated with increased infection rates. The goal should be to

strive for glucose levels of 80–110 mg/dL and certainly to

prevent levels from exceeding 150 mg/dL. In the ICU, hourly

glucose monitoring and aggressive insulin use are commonly

required to achieve this goal. Insulin drips are frequently

necessary, and there should be no reluctance to use them on

a protocol-driven basis. Judicious use of steroids and other

immunosuppressive medications is an important adjunct as

well. For patients with diseases requiring these agents, the

intensivist must balance their use with the need to prevent

and/or treat infections. The same can be said for transfusion

of blood and blood products. As the immunosuppressive

nature of blood transfusion has become increasingly recog-

nized, the elevated risk of surgical infection must be weighed

against the desire to optimize oxygen delivery.

Malnutrition clearly puts patients at risk for infections, and

nutritional support is a signal feature of intensive care. For

many reasons, including lower infection rates, enteral feeding

is preferred over the intravenous route. However, the latter has

the advantage of prompt delivery of full nutritional support.

There should be no hesitation to initiate parenteral nutrition

should tube feedings be unsuccessful or impractical.

Currently, numerous immune-enhanced formulas are avail-

able. Some of the purported benefits are simply due to their

increased protein content, but additionally, there may be clin-

ically significant benefits to increased provision of certain

amino acids (eg, glutamine, arginine, and glycine), nucleic

acids, and omega-3 fatty acids. This is an area of particularly

intense research activity, and critical care physicians should

follow this work closely.

Furnary AP et al: Continuous insulin infusion reduces mortality in

patients with diabetes undergoing coronary artery bypass graft-

ing. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2003;125:1007–21. [PMID:

12771873]

Hill GE et al: Allogeneic blood transfusion increases the risk of

postoperative bacterial infection: A meta-analysis. J Trauma

2003;54:908-14. [PMID: 12777903]

Diagnosis of Surgical Infection in the ICU

Despite the highly technical atmosphere of the ICU, assiduous

physical examination remains the cornerstone for timely diag-

nosis of surgical infections. The presence of complex devices

and dressings, along with the patient’s relative immobility, can

inhibit thorough physical assessment. Diagnostic delays are

commonly attributable to an intubated patient’s inability to

communicate. Fever and leukocytosis often prompt early eval-

uation by CT scan. Negative or equivocal imaging studies are

not uncommonly followed by a revealing physical evaluation

that could have obviated the trip to radiology.

Clues to presence of infection can be subtle. Examples

include unexplained hyperglycemia and gradual worsening of

hepatic, pulmonary, and/or renal functional indices.

Additionally, stagnant or falling nutritional markers such as

prealbumin may signify infection rather than inadequate pro-

vision of calories and nutrients. Immunosuppressed individ-

uals may not manifest the usual signs of infection, and index

of suspicion should be high if the clinical course is not pro-

ceeding smoothly. For these and other critically ill patients,

both overt and subtle indicators of infection warrant blood,

sputum, and urinary cultures. More sophisticated evaluations

also generally will be necessary. It can be quite difficult to dif-

ferentiate true infection from bacterial or fungal colonization.

It takes experience and discipline to react appropriately when

confronted with culture results in critically ill patients.

Fortunately, there are many tools for diagnosing infec-

tions even when their existence is not forthcoming from

physical examination or culture data. Critical care specialists

are increasingly using bedside ultrasound and echocardiog-

raphy. Pleural, pericardial, peritoneal, and soft tissue fluid

collections can be identified and sampled safely. Diagnostic

peritoneal lavage, though largely supplanted by emergency

department ultrasonography for trauma, still has an occa-

sional role in determining the presence of peritonitis in

patients too unstable for travel to the radiology suite.

Intensivists routinely perform fiberoptic endoscopy of all

sorts. This allows accurate and timely diagnosis of pneumo-

nia and infectious esophagitis and colitis. Diagnostic

laparoscopy and pleuroscopy now can be done at bedside.

Imaging studies play a crucial role in the diagnosis of

infection in the critically ill. Ultrasound, CT, and MRI are

sometimes complementary and sometimes competing. It is

often productive to discuss clinical scenarios in depth with

radiology colleagues before sending the patient for one type

of scan or another. This avoids unnecessary excursions from

the ICU and limits suboptimal studies, redundancy, expense,

and patient risk. Of the three, MRI probably is the least use-

ful in evaluation of the unstable ICU patient. In some cases,

though, particularly when CNS infection is a concern, MRI

may be superior. CT scanning and ultrasound, besides pro-

viding high-quality images, allow therapeutic abscess

drainage. To a large extent, this has replaced surgical explo-

ration for management of abdominal and pelvic infections.

Nuclear medicine studies, when selected appropriately, also

serve an important purpose. For example, indium-labeled

white blood cell scans, though of limited utility early in the

postoperative period, can pinpoint the site of infection later

in a patient’s course when other methods have failed.

Beaulieu Y: Bedside echocardiography in the assessment of the crit-

ically ill. Crit Care Med 2007;35:S235–49. [PMID: 17446784]

Nicolaou S et al: Ultrasound-guided interventional radiology in

critical care. Crit Care Med 2007;35:S186–97. [PMID: 17446778]

Treatment of Surgical Infection in the ICU

Significant progress has been made over the past decade rel-

ative to treatment. Advances are attributable to two major

areas: improvement in use of antimicrobial agents and

SURGICAL INFECTIONS

399

advancement in interventional radiology techniques. A

handful of new antibacterial and antifungal agents have been

introduced recently. While these agents have broadened ther-

apeutic options, multidrug-resistant pathogenic strains con-

tinually threaten the ICU patient. By employing newer agents

rationally and using older agents more effectively, the clini-

cian stands a better chance against problematic organisms.

The change to once-daily dosing of aminoglycosides, for

instance, addresses several issues. Higher doses given over

broader time intervals provide greater peak blood levels. This

enhances bacterial killing, whereas low or undetectable

trough levels limit renal and other toxicity. Renal toxicity is a

largely saturable process. Despite high peak levels, only so

much aminoglycoside can be taken up by renal cells per unit

time. Later in the interval, when renal cells could absorb

more antibiotic, there is little available to produce toxic

effects. Other antibiotics work much better when some con-

tinuous minimum level is maintained. Since there appears to

be no augmentation of bacterial killing by pushing levels

higher, lower doses given more frequently (or even by con-

tinuous infusion) provide a persistent satisfactory level to

achieve optimal bactericidal effect. Penicillins and

cephalosporins exemplify this strategy. As newer agents are

introduced, these principles should be borne in mind.

Newer antibiotics have improved options for treating

surgical infections caused by multidrug-resistant strains.

Examples include linezolid to treat methicillin-resistant S.

aureus (MRSA) and tigecycline to combat difficult gram-

negative rods such as Acinetobacter baumannii. To retain

their efficacy, they must be used with discretion. While

broad agents are often necessary at the onset of infection,

there should be a rapid taper to narrower agents once cul-

ture data are available. Again, it is particularly important to

differentiate between bacterial colonization and true infec-

tion so as not to overuse new agents and diminish their

capabilities.

It is worthwhile at times to also consider alternative

routes of antibiotic administration. These include intrathe-

cal, inhalational, enteral, and intracavitary drug delivery.

Several antimicrobial classes have bioavailability via the

enteral route that rivals that of parenteral delivery.

Examples include quinolones and fluconazole. Once tube

feedings are well tolerated, a switch from parenteral to

enteral delivery can be made confidently, limiting adminis-

trative costs and allowing removal of intravenous catheters

that may, in turn, become infected. Finally, a broader array

of antifungal and antiviral agents has become available in

recent years, enhancing treatment options while in many

cases reducing renal and other toxicity. On occasion, a crit-

ically ill patient whose infection is not responding to mul-

tiple antibiotics must be started presumptively on a

systemic antifungal agent despite lack of supportive culture

data. Close collaboration with infectious disease consult-

ants is necessary in these cases.

Duration of antimicrobial coverage is continually

debated. While there is a trend toward limiting treatment

duration, some infections are particularly hard to treat given

the difficulty of antibiotic penetration into the tissues

involved. Examples include endocarditis, osteomyelitis,

sinusitis, and otitis media. When presence of one of these

infections is certain, prolonged antibiotic courses generally

are necessary and accepted. For most other surgical infec-

tions, however, shorter durations are preferable. It has been

well established that peritonitis following perforated diverti-

culitis or appendicitis (after surgical source control) should

be discontinued once fever, leukocytosis, and ileus have

resolved. If these occur even as early as postoperative day 3,

it is reasonable to stop antibiotics then. Failure to meet these

criteria by days 5, 6, or 7 usually means an abscess has

formed. Continued or additional antibiotics likely will be

ineffective, and one should proceed with an abdominopelvic

CT scan searching for a drainable abscess. In most cases,

abscesses thus identified can be treated definitively by CT- or

ultrasound-guided aspiration via percutaneous, transrectal,

or transvaginal routes. This obviates a return to the operat-

ing room and its attendant morbidity. Occasionally, multiple

abscesses are identified, not all of which are amenable to

image-guided drainage. Options then are limited to continu-

ing conservative (ie, broad antibiotic) treatment versus reop-

eration. This decision hinges on the patient’s status. If

substantial leukocytosis or left shift persists, but the patient is

eating well and lacks marked constitutional symptoms, pro-

longed antibiotic therapy may be successful. This is unusual,

though, and most patients with multiple postoperative

abscesses must be taken back to the operating room.

These concepts involving intraabdominal infection are

not new. Limiting duration of treatment and earlier pursuit

of imaging studies have been applied recently to other infec-

tions, however, such as pneumonia. The common goal is to

get the most out of available agents by preserving their effi-

cacy, limiting toxicity and microbial resistance during ther-

apy, and slowing emergence of resistant strains that might

affect future patients. Every institution and its individual

ICUs have their own unique bacterial ecology. This limits

somewhat the broad applicability of treatment guidelines.

Review of institutional antibiograms on a quarterly basis can

positively influence empirical coverage of apparent pneumo-

nias and bloodstream infections while spotlighting emerging

resistance patterns. Antibiotic “crop rotation” has been

employed as a means to stem development of resistant

strains within ICUs, although this concept remains contro-

versial. What is probably more important is for the inten-

sivist to employ all means at his or her disposal to rapidly

identify the site of infection and its causative organism(s),

allowing the most rapid application of the narrowest effec-

tive agent(s). An organized approach to patient assessment

by body region is helpful.

Bennett KM et al: Implementation of antibiotic rotation protocol

improves antibiotic susceptibility profile in a surgical intensive

care unit. J Trauma 2007;63:307–11. [PMID: 17693828]

CHAPTER 16

400

Evaluation and Management of Infection

by Body Site

Head and Neck

CNS infections, including meningitis, ventriculitis, and

intracerebral abscess, must be considered in patients who

have sustained head injury or have undergone neurosurgical

procedures. Patients with skull base and paranasal fractures

are included in this group. Use of intraparenchymal cerebral

pressure (ICP) monitors and ventriculostomy catheters, while

applied appropriately along guidelines for severe head injury

management, is associated with serious infection risk.

Previously, antibiotic prophylaxis was used for the duration of

ICP monitor presence and for 5–7 days following diagnosis of

skull base or paranasal sinus fractures. It is now recognized

that this exerts pressure toward infection by multidrug-

resistant organisms. Controlled data are lacking as to appro-

priate antibiotic use in these patients, but it is clear that the

indiscriminant use of antibiotics in these settings is associated

with difficult-to-treat secondary infections. With regard to

transcranial pressure monitors, it is hoped that with sterile

technique at placement, fastidious fluid sampling, prudent

antibiotic use, and device removal as early as feasible, occur-

rence of serious infections will diminish.

Another important consideration is infection in and

around the eye. As mentioned earlier, ocular inflammation

often goes unnoticed in the complex ICU patient. Problems

not considered go undiagnosed, and any abnormal ocular

finding should prompt early ophthalmologic consultation as

appropriate. Periorbital cellulitis is of particular concern

because therapeutic delay can result in the catastrophic com-

plication of cavernous sinus thrombosis.

Given the ubiquitous use of nasogastric tubes, paranasal

sinusitis remains a risk. There may or may not be associated

purulent nasal drainage. It is important to remember this not

infrequent but often undiagnosed infection in the febrile

critically ill patient. CT scan is far superior to plain films for

making this diagnosis. Surgical drainage sometimes must

augment antibiotics to clear this infection. It is best to avoid

this condition altogether by choosing the oral over the nasal

route for enteral decompression and feeding in orotracheally

intubated patients. Dental abscess, simple or complicated,

should be considered in the febrile, critically ill patient, par-

ticularly when dentition is poor. These and pharyngeal infec-

tions can evolve into life-threatening necrotizing infections

that can descend transcervically into the chest (ie, acute

necrotizing mediastinitis). The cervical component of this

process is not difficult to recognize given neck edema,

induration, and erythema, but the thoracic component can

have protean manifestations. New and unexplained pleural

fluid noted on chest x-ray is an important early finding.

Central line infections contribute significantly to mor-

bidity and mortality in surgical patients. In the United States,

about 200,000 nosocomial bloodstream infections occur annu-

ally, the majority of which are associated with the presence of

intravascular catheters. Internal jugular and femoral venous

catheters previously carried higher infection rates than those

in the subclavian position, but recent preventive strategies

have perhaps neutralized this difference. Such measures

include perfect sterile technique at placement, chlorhexidine

site preparation, selection of catheters with antibacterial

coatings, use of antiseptic site dressings, and device removal

as early as possible. Application of catheter-site antibiotic

ointments should be avoided because they encourage devel-

opment of infection by resistant bacteria and fungi. Rotation

of catheter sites on a scheduled basis is not helpful, and

catheter changes over a guidewire should be kept to a mini-

mum. In certain situations, vascular access may be exceedingly

difficult. Despite development of fever or leukocytosis, risk-

benefit analysis may favor guidewire exchange over attempting

placement at a new site. However, the removed catheter tip

should be sent for culture. A positive culture mandates

immediate removal of the catheter that replaced the original

one. Infection also can be introduced via the catheter hub,

and those accessing the catheter must maintain strict sterile

technique.

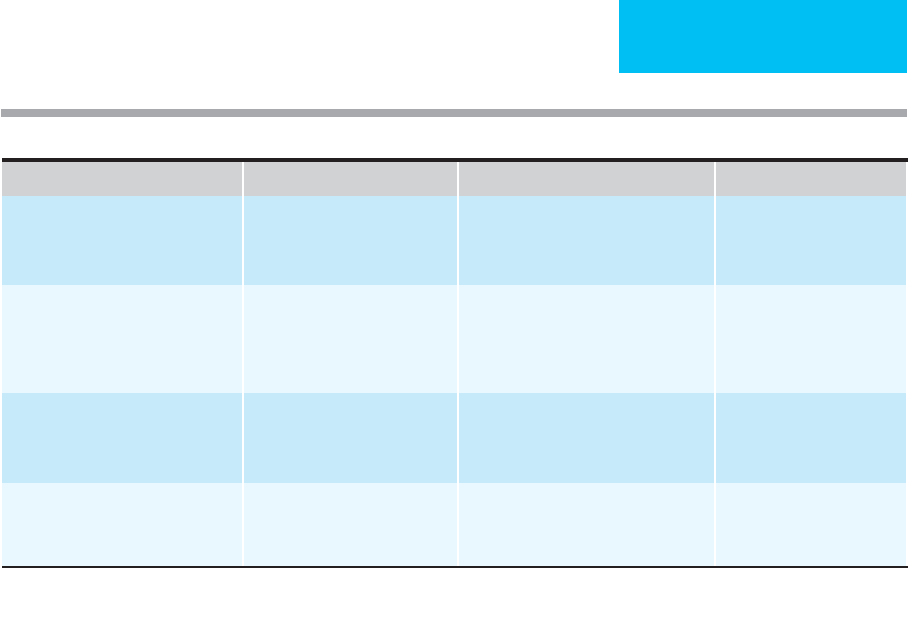

Treatment of head and neck infections is summarized in

Table 16–1.

Gilbert DN et al (eds): The Sanford Guide to Antimicrobial Therapy,

37th ed. Sperryville, VA: Antimicrobial Therapy, Inc., 2007.

Kuminsky RE: Complications of central venous catheterization.

J Am Coll Surg 2007;204:681–96. [PMID: 17382229]

Taylor RW, Palagiri AV: Central venous catheterization. Crit Care

Med 2007;35:1390–6. [PMID: 17414086]

Chest

Ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) is the most com-

mon infection in the surgical ICU. VAP is defined as pneu-

monia occurring at least 48–72 hours following

endotracheal intubation. There is debate as to whether or

not VAP independently increases mortality, but it clearly

lengthens ICU stay, increases patient days on the ventilator,

and adds tremendously to health care expenditures.

Antibiotic therapy for VAP is often complex and prolonged,

adversely affecting an ICU’s bacterial ecology. Over recent

years, much effort has been expended to better characterize

the pathophysiology, diagnosis, and proper treatment of

VAP. There is no diagnostic “gold standard,” and treatment

is complicated by undisciplined antibiotic administration

with vague treatment endpoints. The Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention original criteria for pneumonia (ie,

fever, leukocytosis, positive sputum Gram stain, and new or

changing pulmonary infiltrate) have proven insufficient for

diagnosis of VAP in the complicated, critically ill patient. In

patients with a markedly abnormal chest x-ray because of

acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), it is often

impossible to identify a new infiltrate superimposed on the

background of noncardiogenic pulmonary edema.

Although VAP diagnosis and treatment remain problematic,

SURGICAL INFECTIONS

401

its causes have become better understood. Presence of an

endotracheal tube (ETT) allows contaminated oropharyn-

geal secretions to circumvent natural protective barriers.

The endotracheal tube, impaired host immunity, and lurk-

ing environmental pathogens conspire to produce VAP in

the critically ill surgical patient. Negative effects of blood

transfusion, hyperglycemia, and malnutrition, so commonly

seen in the ICU, elevate risks further.

There has been a strong push lately to improve the preven-

tion and management of VAP. Influential multidisciplinary

societies (eg, the American Thoracic Society and the Infectious

Disease Society of America) have promulgated clinical guide-

lines. These ICU “bundles” promote consistency in approach

within and across institutions. Prevention strategies include

head-of-bed elevation 30–45 degrees (or reverse Trendelenburg

position when thoracic spine stability is in question) and

avoidance of gastric distention to minimize aspiration of gas-

tric contents, use of ETTs with suction ports to remove secre-

tions pooling above the ETT cuff, use of sleeved suction

catheters, and improved oral hygiene. Selective gut decontami-

nation has been advocated, but its value is questionable because

enteric organisms generally are not responsible for VAP. The

most common offending organisms are MRSA and species of

the genera Pseudomonas, Acinetobacter, and Stenotrophomonas.

Minimizing transfer of these pathogens from one patient to

another is another key to prevention. Finally, since the inci-

dence of VAP correlates with a patient’s duration of intubation,

any prevention program should include an aggressive strategy

for liberation from the ventilator.

Diagnosis of pneumonia is usually not difficult in the

emergency department. History, physical findings, and

chest x-ray generally suffice. For the intubated ICU patient,

development of fever, leukocytosis, and apparent purulent

sputum raise the question of pneumonia, but establishing a

confident diagnosis may be difficult. Both chest x-ray and

tracheal sputum aspirate analysis lack specificity in these

patients. A normal chest x-ray excludes the diagnosis. When

the chest x-ray is abnormal, the next step is to obtain a reli-

able sputum sample for performance of quantitative analy-

sis. Preferred methods are use of a protected-specimen

brush (PSB) and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL).

Commonly used thresholds for confirming pneumonia are

10

3

colony-forming units (cfu)/mL for PSB and 10

4

cfu/mL

for BAL. These techniques, which require bronchoscopy,

are expensive and time-consuming. However, they more

firmly establish the correct diagnosis and direct appropri-

ate antibiotic therapy. More recently, catheters have been

developed that allow reliable sampling by the respiratory

therapist, eliminating need for bronchoscopy. Both PSBs

and mini-BAL sets are available and are enjoying wider use.

The goals are to distinguish between infection and colo-

nization and, if infection is present, to determine the

offending organism(s) as soon as possible so that treatment

can be tailored specifically.

Diagnosis Organisms Initial Antibiotics Adjunctive Therapy

Meningitis and ventriculitis

S. pneumoniae, S. aureus,

coliforms,

P. aeruginosa,

Acinetobacter

sp.

Vancomycin 500–750 mg IV q6h +

cefepime or ceftazidime 2 g IV q8h

or

meropenem 2 g IV q8h + vancomycin

1 g IV q6–12h

Removal of intracerebral

device, intrathecal antibiotic

administration

Periorbital cellulitis

S. pneumoniae, Haemophilus

influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis,

S. aureus, group A

Streptococcus

sp.

Nafcillin-oxacillin 2 g IV q4h (if MRSA,

vancomycin 1 g IV q12h) + ceftriaxone

2 g IV q24h + metronidazole 1 g IV q12h

IV heparin for cavernous sinus

thrombosis if present

Paranasal sinusitis Gram-negative bacilli,

S. aureus

Imipenem 500 mg IV q6h

or

meropenem

1 g IV q8h

or

ceftazidime 2 g IV q8h

or

cefepime 2 g IV q12h (for possible

MRSA, add vancomycin 1 g IV q12h)

Removal of nasoenteric tube,

aspiration of fluid from sinus

Central line infection

S. aureus

(MSSA, MRSA),

S. epidermidis,

enterococci

Vancomycin 1 g IV

or

linezolid 600 mg

IV q12h

Removal of catheter, vein

resection if suppurative

thrombophlebitis

Data from Gilbert DN et al (eds): The Sanford Guide to Antimicrobial Therapy, 37th ed. Sperryville, VA: Antimicrobial Therapy, Inc., 2007.

Table 16–1. Summary of head and neck infections in adult surgical patients.

CHAPTER 16

402

Aggressive treatment should immediately follow acquisi-

tion of a good sputum sample. Antibiotic selection depends

on the prevailing organisms within an individual ICU.

Offending bacteria change over time, justifying quarterly

analysis of cultures and resistance patterns. In general, initial

therapy should cover MRSA and the difficult gram-negative

rods. It is important to start broadly because delays in appro-

priate coverage may lead to increased mortality. Once reliable

microbiologic data are available, antibiotic coverage should

be tailored immediately to the narrowest bactericidal agent

to which the organism is sensitive. Previously, it was recom-

mended that two antibiotics with different mechanisms of

action should be used to treat the multidrug-resistant gram-

negative rods. This was extrapolated from the neutropenic

cancer patient population and applied to other groups.

Supportive data are lacking for the surgical ICU population,

and single-agent therapy appears to be satisfactory. When

final microbiologic data do not support the diagnosis of VAP,

and the patient is not deteriorating, it is reasonable to stop

antibiotics altogether. If culture results are equivocal and/or

the patient’s condition is worsening, it is appropriate to con-

tinue broad antibiotic coverage, but a firm endpoint of about

7 days should be selected early. In the majority of cases, cul-

ture and sensitivity results will guide selection of the narrow-

est appropriate antibiotic, and duration of therapy can be

determined by the patient’s response.

Antibiotics with high enteral bioavailability often can be

converted safely from intravenous to enteral administration

early in the treatment process. Inhaled administration of

antimicrobials should be considered in some instances.

Pneumonia can be difficult to treat, even with the correctly

chosen and delivered agent, and courses of 10–14 days are

often necessary. Patients with blood and respiratory cultures

growing the same organism have a more serious infection

and generally will need a longer antibiotic course. However,

improvement should be seen within 1 week, and if this has

not occurred, a prolonged antibiotic course is not likely to be

effective. Failure of a timely response should prompt a search

for complications of pneumonia such as pulmonary abscess

or empyema or consideration of an alternative infection

diagnosis. CT scanning is important in this assessment.

Another important surgical infection is empyema, or pus

in the pleural space. Indicative findings on pleural fluid

analysis are pH less than 7.20, organisms present on Gram

stain, and a positive culture. Ultrasound is helpful to guide

safe aspiration of pleural fluid. Surgical patients at risk are

those who have had VAP, blunt or penetrating trauma, tho-

racostomy tube placement, or thoracotomy. CT scan defines

the empyema’s extent. Treatment options include thoracos-

tomy tube placement, instillation of tissue plasminogen acti-

vator (tPA), video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) or

open thoracotomy with lung decortication, and open

drainage. Choice of treatment is influenced by the duration

of the process, the pleural fluid distribution, and the patient’s

condition. The three stages of empyema are the early exuda-

tive stage, the intermediate fibrinopurulent stage, and the late

organization stage. A simple empyema in its early stage often

can be well managed with a chest tube and antibiotics.

Beyond antibiotics, the goals are to drain all the infected fluid

and eliminate all free intrapleural space. Generally, the

admonition of “no space, no problem” applies. The chest

tube does not always have to be of large caliber. A single loc-

ulated collection not draining adequately via a well-placed

thoracostomy tube may respond to dissolution by a throm-

bolytic agent. This can be effective, but it is best done in col-

laboration with the surgeon who would operate if

thrombolytics fail because subsequent operative intervention

can be rendered much more difficult.

Multiple loculated fluid collections and more advanced

empyema stages are best dealt with surgically (VATS or tho-

racotomy). For the critically ill or severely debilitated patient,

rib resection and drainage may be the best approach, allow-

ing the space to heal from the inside out as the thoracostomy

tube is slowly withdrawn over weeks to months. A special

empyema subset is that occurring early after pneumonec-

tomy. The majority of these are due to a breakdown of the

bronchial stump. The problem is manifested by a productive

cough, dyspnea, and sepsis. The first maneuver is to place a

thoracostomy tube to drain the infected fluid that will

diminish the septic focus and prevent spread of infection to

the remaining lung. Open thoracostomy with bronchial

repair and muscle or omental flap coverage are required then

to correct the process. Eventually, the chest can be closed over

a pleural space filled with antibiotic solution, with expecta-

tion of success in most cases.

Two other major chest infectious processes are mediastini-

tis and endocarditis. Mediastinitis can occur as a postopera-

tive infection following median sternotomy, as a result of

spontaneous or iatrogenic esophageal perforation, or as a

descending necrotizing process originating from oropharyn-

geal or odontogenic infection. Sternal wound infection after

cardiac surgery can be superficial, responding to antibiotics

and local wound care. Associated life-threatening mediastini-

tis occurs in just over 1% of cardiac surgery patients, with the

incidence in children approximating that in adults. One adult

group at higher risk is diabetic women undergoing bilateral

internal thoracic artery harvest. Fever, leukocytosis, sternal

instability, and wound erythema and drainage warn of this

problem, and a new pleural effusion adds to the probability.

Treatment includes administration of intravenous antibiotics,

surgically evacuating all purulent fluid and necrotic soft tissue

and bone, and either reclosing the sternum over an inflow-

outflow antibiotic delivery system or filling the defect with

pedicled muscle or omental flaps. Esophageal perforation

occurs most commonly now as a complication of endoscopy.

Small tears occasionally can be managed with antibiotics with

or without stent placement, provided that there is no free flow

of diagnostic contrast agent into the mediastinum or pleural

space. Most esophageal perforations require thoracoscopic or

open pleural drainage, mediastinal debridement, and

esophageal repair over a bougie when feasible. Generally, tears

in the upper two-thirds of the esophagus are approached via

SURGICAL INFECTIONS

403

right posterolateral thoracotomy and those in the distal third

by way of left posterolateral thoracotomy.

Acute necrotizing mediastinitis (ANM) is third major

form of mediastinitis. It is a destructive, life-threatening

process usually originating in the oropharyngeal region and

extending transcervically into the mediastinum along con-

tinuous fascial planes. While the cervical component is easy

to recognize, mediastinal involvement is less obvious, caus-

ing significant diagnostic delays. Management includes

prompt institution of broad-spectrum intravenous antimi-

crobials to cover oropharyngeal aerobes and anaerobes,

immediate contrast-enhanced cervicothoracic CT scanning,

and urgent surgical therapy directed at the oropharyngeal,

cervical, and thoracic components. Tracheostomy should be

applied selectively. Occasionally, mediastinal involvement

confined to the upper anterior mediastinal aspect may be

amenable to drainage via the transcervical approach, but the

potential for rapid, diffuse spread deeper into the medi-

astinum must be anticipated and dealt with accordingly.

Minimally invasive approaches have been reported, but gen-

erally they are inadequate to treat this process. A team of sur-

geons including otolaryngologists and thoracic surgeons

(and maxillofacial surgeons in the presence of odontogenic

infection) serves the patient best. At the outset, surgeons

should acknowledge the likely need for multiple operations.

Endocarditis can be seen in surgical patients. This diag-

nosis is particularly likely in the febrile patient with a posi-

tive blood culture and new murmur. Other classic signs of

endocarditis (eg, splinter hemorrhages, Osler’s nodes, and

Janeway’s lesions) are often absent in acute endocarditis.

Risk factors include intravenous drug abuse (IVDA), poor

dental hygiene, long-term hemodialysis, diabetes mellitus,

mitral valve prolapse, and rheumatic heart disease. In the

ICU, endocarditis can occur in patients admitted for other

reasons but who require multiple intravascular catheters.

Enterococci, though overwhelmingly associated with bac-

teremia rather than endocarditis, can be a cause of endo-

carditis in this patient group, and the organisms are

commonly resistant to many antibiotics. Previously, viridans

streptococci led the list of causative bacteria. In most recent

series, S. aureus predominates. Polymicrobial endocarditis is

unusual and generally associated with IVDA. Blood cultures

positive for Streptococcus bovis suggest a colon lesion in

older patients, warranting colonoscopy. Endocarditis

involves native valves 75–93% of the time, with prosthetic

valve infection comprising the remainder. As for the latter,

infections occurring within 2 months of surgery are thought

to be hospital-acquired. If onset exceeds 12 months from

time of surgery, the endocarditis is considered community-

acquired. Between 2 and 12 months, valve infection can be

either origin.

Echocardiography is the primary diagnostic modality

for endocarditis. Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE)

has sensitivity as low as 70% but a specificity approaching

98% for identification of the characteristic vegetations.

When suspicion remains high despite a negative TTE, or

additional detail is required for operative planning, trans-

esophageal echocardiography (TEE) is indicated. TEE sen-

sitivity for endocarditis is around 95%, with a negative

predictive value around 92%. Despite its more invasive

nature, TEE offers a much better view of the cardiac inte-

rior. TEE is particularly valuable for assessment of pros-

thetic valves and evaluation for myocardial abscess. The

latter is associated with conduction system disturbances.

Surgery is indicated urgently to address acute valvular

incompetence, myocardial abscess, or continued septic

embolization despite apparently adequate antibiotic cover-

age. Sometimes multiple cultures are negative in the febrile

patient with a positive echocardiogram. If the laboratory is

alerted to this situation, special culture techniques can be

employed to capture fastidious organisms. For patients

undergoing surgery, the polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

can be run to identify otherwise unculturable organisms

obtained from valve tissue or peripheral emboli.

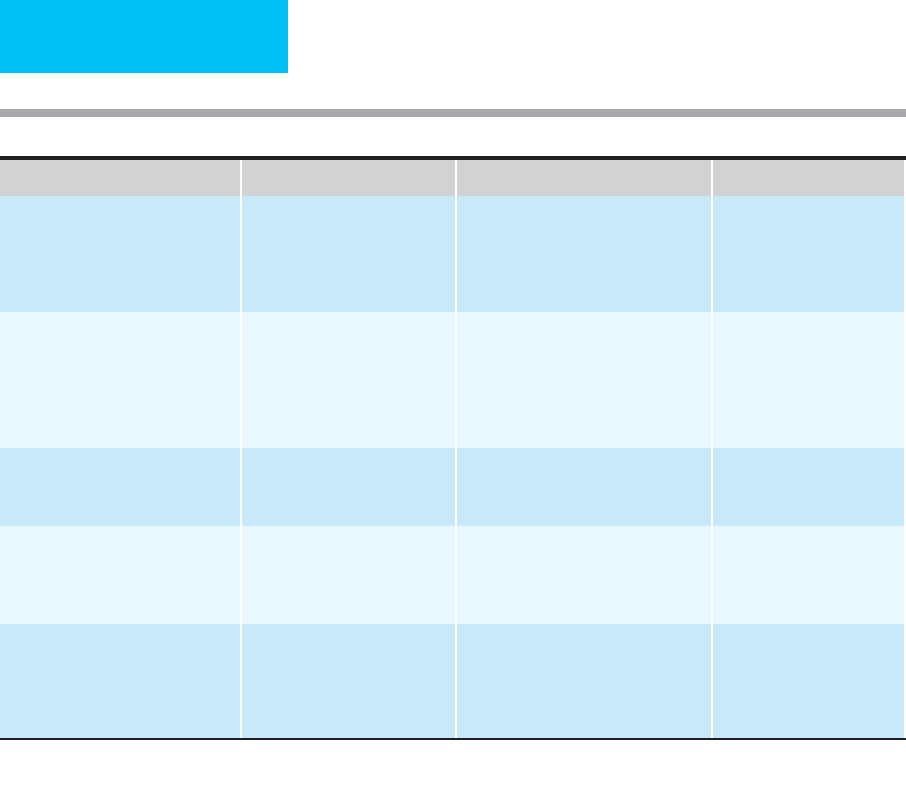

Treatment of thoracic infections is summarized in

Table 16-2.

American Thoracic Society: Executive summary: Guidelines for

the management of adults with hospital-acquired, ventilator-

associated, and healthcare-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir

Crit Care Med 2005;171:388–416. [PMID: 15699079]

Cocanour CS et al: Decreasing ventilator-associated pneumonia in

a trauma ICU. J Trauma 2006;61:122–30. [PMID: 16832259]

Freeman RK et al: Descending necrotizing mediastinitis: An analy-

sis of the effects of serial surgical debridement on patient mor-

tality. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2000;119:260–7. [PMID:

10649201]

Gilbert DN et al (eds): The Sanford Guide to Antimicrobial Therapy,

37th ed. Sperryville, VA: Antimicrobial Therapy, Inc., 2007.

Light RW: Parapneumonic effusions and empyema. Proc Am

Thorac Soc 2006;3:75–80. [PMID: 16493154]

Minei JP et al: Guidelines for prevention, diagnosis and treatment

of ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) in the trauma

patient. J Trauma 2006;60:1106–13. [PMID: 16688078]

Mylonakis E, Calderwood SB: Infective endocarditis in adults.

N Engl J Med 2001;345:1318–30. [PMID: 11794152]

Pierracci FM, Barie PS: Strategies in the prevention and manage-

ment of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Am Surg 2007;73:

419–32. [PMID: 17520992]

Abdomen and Pelvis

This broad class includes infections of the GI mucosa or full

bowel thickness, visceral infarction, abscesses, and diffuse

peritonitis. Infections also occur secondary to mechanical

blockage of the biliary tract (eg, ascending cholangitis and

cholecystitis), urinary tract (eg, pyelonephritis and cystitis),

and female internal genitalia (eg, tubo-ovarian abscess and

pelvic inflammatory disease). Peritonitis occurs in primary,

secondary, and tertiary forms. Primary (spontaneous) bacte-

rial peritonitis truly can be spontaneous (eg, Pneumococcal

peritonitis seen in young girls) or more commonly a compli-

cation in cirrhotic patients with ascites or in those receiving

CHAPTER 16

404

peritoneal dialysis. Tuberculous and other granulomatous

forms of peritonitis also are included in this group. In these

instances, there is no leak of organisms from the GI tract.

Secondary peritonitis occurs when there is perforation of a

hollow viscus, such as in duodenal ulcer, anastomotic leak,

appendicitis, or diverticulitis. The further along the GI tract

a perforation occurs, the higher is the bacterial density.

Whereas gastroduodenal perforations are best described as

causing chemical peritonitis complicated by the presence of

bacteria, colonic perforation delivers an enormous load of

bacteria into a peritoneal space that secondarily becomes an

altered, low-pH environment. Sometimes perforations are

contained by surrounding structures such as omentum or

adjacent bowel loops. This produces focal rather than diffuse

peritonitis that is often amenable to antibiotic therapy with

or without percutaneous drainage. Surgical therapy can be

postponed or even avoided altogether. Patients often can be

spared the two-stage emergency procedure with its associ-

ated temporary colostomy. Examples include perforated

appendicitis and diverticulitis with abscess. Diffuse second-

ary peritonitis, on the other hand, requires urgent operative

intervention.

Two phases of secondary peritoneal infections have been

described. Initially, hundreds of bacterial species exit into the

peritoneum on colonic perforation, but within short order

these numbers are reduced to two or three pathogenic

species (simplification). These organisms are predictable

because only a few species can survive in the unusual envi-

ronment of peritonitis: obligate anaerobes such as

Bacteroides fragilis and endotoxin-producing members of the

family Enterobacteriaceae that includes facultative anaerobes

such as Escherichia coli. These bacteria work together (syner-

gism) to produce both abscess formation and systemic sepsis.

Included in this synergistic relationship are Enterococcus

species, at least with regard to abscess formation and wound

infection. However, Enterococcus is of questionable impor-

tance when the other two groups are surgically reduced and

then eliminated by appropriate antibiotics and host defenses.

Diagnosis Organisms Initial Antibiotics Adjunctive Therapy

Ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP)

S. pneumoniae, S. aureus,

P. aeruginosa, Acinetobacter

sp.,

Stenotrophomonas maltophilia,

coliforms, anaerobes

Imipenem 500 mg IV q6h

or

meropenem

1 g IV q8h (+ vancomycin 1 g IV q12h if

ICU MRSA pneumonia rate high)

or

cefepime 2 g IV q8h

or

high-dose

piperacillin-tazobactam + vancomycin

Prevention, quantitative

sputum cultures, ICU

antibiogram

Empyema

S. pneumoniae, S. aureus

(consider MRSA),

S. pyogenes,

S. milleri, H. influenzae,

Bacteroides

sp.,

Enterobacteriaceae

Cefotaxime 1–2 g IV q4–12h

or

ceftriax-

one 1–2 g IV q24h (+ clindamycin

450–900 mg IV q8h for possible anaer-

obes)

or

nafcillin-oxacillin 2 g IV q4h

(MSSA)

or

vancomycin 1 g IV q12h

(MRSA)

Thoracostomy tube,

intrapleural thrombolytics,

VATS, thoracotomy

Mediastinitis after sternotomy

S. aureus,

possible MRSA Vancomycin 1 g IV q12h Surgical debridement, medi-

astinal inflow-outflow

catheters

Other mediastinitis MRSA/MSSA, coliforms,

Bacteroides

sp., and other

anaerobes

Piperacillin-tazobactam 3.375 g IV q6h

(

or

ceftazidime 2 g IV q8h + metronidazole

15 mg/kg IV q12h

or

a carbapenem IV)

+ vancomycin 1 g IV q12h

Surgical debridement

Endocarditis

S. aureus, S. epidermidis

(prosthetic valve),

viridans

strep,

S. bovis,

enterococci

Vancomycin 1 g IV q12h + gentamicin

1–1.5 mg/kg IV q8h × 14 days

or

(for

penicillin-sensitive organisms) penicillin

G 18–30 million units in divided doses IV

q4h + gentamicin

Valve repair or replacement,

myocardial debridement

Data from Gilbert DN et al (eds): The Sanford Guide to Antimicrobial Therapy, 37th ed. Sperryville, VA: Antimicrobial Therapy, Inc., 2007.

Table 16–2. Summary of thoracic infections in adult surgical patients.

SURGICAL INFECTIONS

405

Wound infection is largely eliminated by the practice of leav-

ing the cutaneous portion of the surgical wound open to

allow healing by secondary intention. Addition of ampicillin

or other antienterococcal antibiotics (part of the old main-

stay of “triple antibiotic coverage”) is now considered

anachronistic. Since the mid-1990s, appropriate antibiotic

treatment of secondary peritonitis has included metronida-

zole to cover most strains of B. fragilis and a non-

antipseudomonal third-generation cephalosporin to cover

the important Enterobacteriaceae organisms. This remains a

reasonable combination today, although some single-agent

strategies have shown equivalent efficacy. Intraoperative

peritoneal cultures are of little value because the important

pathogens are predictable from the pathophysiology.

Overall, the management goals for secondary peritonitis

as outlined by Wittmann, Schein, and Condon in the mid-

1990s remain true today. Supportive treatment includes pro-

vision of appropriate antibiotics, treatment of hypovolemia

and shock, optimizing tissue oxygenation, nutritional sup-

port, and support of failing organ systems. Surgical measures

include early source control, mechanical cleansing of the peri-

toneal cavity, recognition and avoidance of abdominal com-

partment syndrome, and identification and drainage of

persistent or recurrent infection. As discussed earlier, antibi-

otic treatment is necessary only until there is absence of fever,

normalization of leukocytosis, and resolution of ileus.

Presence of any of these beyond 5–7 days prompts a search for

undrained infection, not addition of extra antibiotics. Culture

of fluid collected with image-guided drainage may be of value

to direct adjunctive antibiotic therapy at this stage.

Tertiary peritonitis is an entity occurring late in the

course of treatment for secondary peritonitis. In patients

with persistent multiple-organ dysfunction after seemingly

appropriate treatment of intestinal perforation, diligent

searches for undrained infection are usually undertaken.

Abdominal or pelvic collections revealed by CT scan are

tapped, only to demonstrate organisms of low pathogenicity.

Unfortunately, the finding of organisms like S. epidermidis,

Candida albicans, and even A. baumannii only confirms the

existence of tertiary peritonitis rather than suggesting defin-

itive antimicrobial treatment. This really only identifies one

more organ that is failing, the peritoneum. Drainage of such

collections and intensifying antibiotic coverage probably

provide little benefit. Optimization of nutritional support

and oxygen delivery are at least as effective as seemingly more

direct measures.

There are a number of other life-threatening intraabdom-

inal infections besides peritonitis. Examples include ascend-

ing cholangitis, gangrenous cholecystitis, and necrotizing

pancreatitis. Acute biliary obstruction in and of itself does not

require urgent intervention. However, when coupled with

fever, leukocytosis, and hemodynamic changes, biliary tract

decompression in needed emergently. Causative bacteria are

predictably enteric organisms, primarily anaerobes and gram-

negative rods, and antibiotic selection is straightforward in

most cases. High blood levels of appropriate antimicrobials

are more helpful than high biliary concentrations. More

important than antibiotic therapy is prompt biliary drainage

via endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP).

When ERCP is either unavailable or unsuccessful, percuta-

neous or surgical drainage is required. Gangrenous cholecys-

titis, identified by the presence of air in the gallbladder wall

noted on imaging studies, requires urgent cholecystectomy.

Other forms of cholecystitis, including the acalculous form

complicating critical illness, can be treated by percutaneous

transhepatic cholecystostomy tube placement. The transhep-

atic route prevents spillage of any purulent fluid into the peri-

toneal cavity. Interval cholecystectomy can be performed

when the patient’s condition has improved.

Pancreatic infections can be particularly difficult to sort

out. Severe pancreatitis without sepsis can produce fulminate

SIRS and ARDS that can be confused with sepsis. Presence of

air bubbles within an edematous or necrotic pancreas indi-

cates infection requiring an aggressive surgical approach. In

the absence of this finding, the deteriorating patient with

necrotizing pancreatitis should undergo CT-guided fine-

needle aspiration for Gram stain and culture of the most

prominently involved area. Although this risks introducing

infection to sterile pancreatic necrosis, high mortality can be

expected if true infection is missed and surgery is withheld.

Recently, a number of minimally invasive approaches have

been reported for the surgical management of this problem.

As for other necrotizing infections, however, the need for

multiple surgical interventions should be anticipated. When

infection is not present, the value of pancreatic necrosectomy

in the critically ill is controversial. The value of prophylactic

systemic antibiotics (eg, carbapenems), widely employed

previously, has been debated recently. Other pancreatic infec-

tions, such as infected pseudocyst, often are amenable to per-

cutaneous drainage. Creative combinations of endoscopic

and transcutaneous drainage can eliminate the need for

complex open surgery in many cases.

Other important surgical infections of the abdomen and

pelvis include a variety of abscesses (eg, subdiaphragmatic,

hepatic, splenic, and perinephric), and complications of

blunt and penetrating trauma, gastroenteritis, bowel

ischemia, inflammatory bowel disease (ie, Crohn’s and ulcer-

ative colitis), vasculitis, antibiotic-associated colitis, and sex-

ually transmitted diseases in women. Appropriate treatment

includes attention to the primary causes.

Whether owing to hemorrhage, SIRS, or septic shock, vis-

ceral and peritoneal edema can produce a dangerous rise in

intraabdominal pressure. Physical findings include abdomi-

nal distention, respiratory distress, and measured urinary blad-

der pressures exceeding 30 mm Hg. Patients on mechanical

ventilation manifest progressive elevation of peak inspiratory

pressures and an increasing P

CO

2

. Urine output falls, probably

owing to compression of renal veins. Decompressive laparo-

tomy is indicated to prevent a downhill spiral toward irre-

versible organ dysfunction and death.

Treatment of abdominal and pelvic infections is summa-

rized in Table 16-3.

CHAPTER 16

406

Marshall JC, Innes M: Intensive care unit management of intraab-

dominal infection. Crit Care Med 2003;31:2228–37.

Wittmann DH, Schein M, Condon RE: Management of secondary

peritonitis. Ann Surg 1996;224:10–8. [PMID: 8678610]

Soft Tissues of the Extremities and Torso

Serious soft tissue infection is another common reason for

surgical ICU admission. Cellulitis and soft tissue abscesses

can occur in patients admitted to the ICU for other conditions.

ICU clinicians commonly care for patients with compli-

cated diabetic foot infections either because of the com-

plexity of the infection or for acute management of

advanced cardiovascular disease so frequently seen in these

patients. Necrotizing fasciitis affecting the extremities and

Fournier’s gangrene are two life-threatening infectious

processes often faced by intensivists. Less commonly seen

but equally lethal is suppurative thrombophlebitis. Most of

these infections are caused by multiple organisms working

synergistically to produce tissue destruction, bacteremia,

Diagnosis Organisms Initial Antibiotics Adjunctive Therapy

Primary peritonitis Enterobacteriaceae,

S. pneumoniae,

enterococci,

anaerobes,

S. aureus,

∗

S. epider-

midis,

∗

P. aeruginosa

∗

Cefotaxime 2 g IV q4–8h

or

ticarcillin-

clavulanate 3.1 g IV q6h

or

piperacillin-

tazobactam 3.375 g IV q6h

or

ampicillin-sulbactam 3 g IV q6h

or

ceftriaxone 2 g IV q24h or ertapenem

1 g IV q24h

Removal of PD catheter as

indicated

Secondary peritonitis Enterobacteriaceae,

Bacteroides

sp., enterococci,

P. aeruginosa

Ceftriaxone 1–2 g IV q24h + metronida-

zole 1 g IV q12h

or

imipenem 500 mg IV

q6h

or

meropenem 1 g IV q8h

Surgical source control, peri-

toneal washout, prevention

and treatment of abdominal

compartment syndrome

Tertiary peritonitis

S. epidermidis, Candida

sp.,

vancomycin-resistant enterococci

(VRE),

Acinetobacter

sp.

Antimicrobial agents of questionable

benefit

Supportive care, optimization

of O

2

delivery, nutritional

therapy, percutaneous or sur-

gical drainage

Biliary tract infection, including

ascending cholangitis (AC)

Enterobacteriaceae, enterococci,

Bacteroides

sp.,

Clostridium

sp.

Ceftriaxone 1–2 g IV q24h + metronida-

zole 1 g IV q12h

or

piperacillin-

tazobactam 3.375–4.5 g IV q6–8h

or

ampicillin-sulbactam 3 g IV q6h

or

ticarcillin-clavulanate 3.1 g IV q6h or

carbapenems IV

ERCP with sphincterotomy ±

stent placement, percuta-

neous transhepatic biliary

drainage, or surgical common

bile duct decompression

for AC

Pancreatic infections Enterobacteriaceae, enterococci,

S. aureus, S. epidermidis,

anaerobes,

Candida

sp.

Same as for biliary tract infection,

guided by fine-needle aspiration results

Prophylactic antimicrobials

controversial for sterile pan-

creatic necrosis, surgical

drainage/debridement, ERCP

with stent PD stent place-

ment, nutritional support

Pelvic inflammatory disease

Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia

trachomatis, Bacteroides

sp.,

Enterobacteriaceae,

Streptococcus

sp.

(Cefotetan 2 g IV q12h

or

cefoxitin 2 g

IV q6h + doxycycline 100 mg IV/PO

q12h)

or

(clindamycin 900 mg IV q6h +

gentamicin 4.5 mg/kg IV q24h, then

doxycycline 100 mg PO bid × 14 days)

Several alternative antibiotic

regimens available

∗

Peritoneal dialysis (PD).

Data from Gilbert DN et al (eds): The Sanford Guide to Antimicrobial Therapy, 37th ed. Sperryville, VA: Antimicrobial Therapy, Inc., 2007.

Table 16–3. Summary of abdominal and pelvic infections in adult surgical patients.