Bongard Frederic , Darryl Sue. Diagnosis and Treatment Critical Care

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

IMAGING PROCEDURES

177

General Considerations

Toxic megacolon is a complication of many different types of

ischemic, inflammatory, or infectious conditions of the colon

but is most closely associated with ulcerative colitis. Patients

are usually in extremis, complaining of fever and bloody diar-

rhea. Tachycardia and abdominal pain may be present.

Clinical features are accompanied by thickened colonic haus-

tra on plain radiographs. Due to the transmural nature of the

inflammation, the neuromuscular and neurohumoral tone of

the colon is disrupted. Without treatment, the mortality rate

is nearly 20%.

Radiographic Features

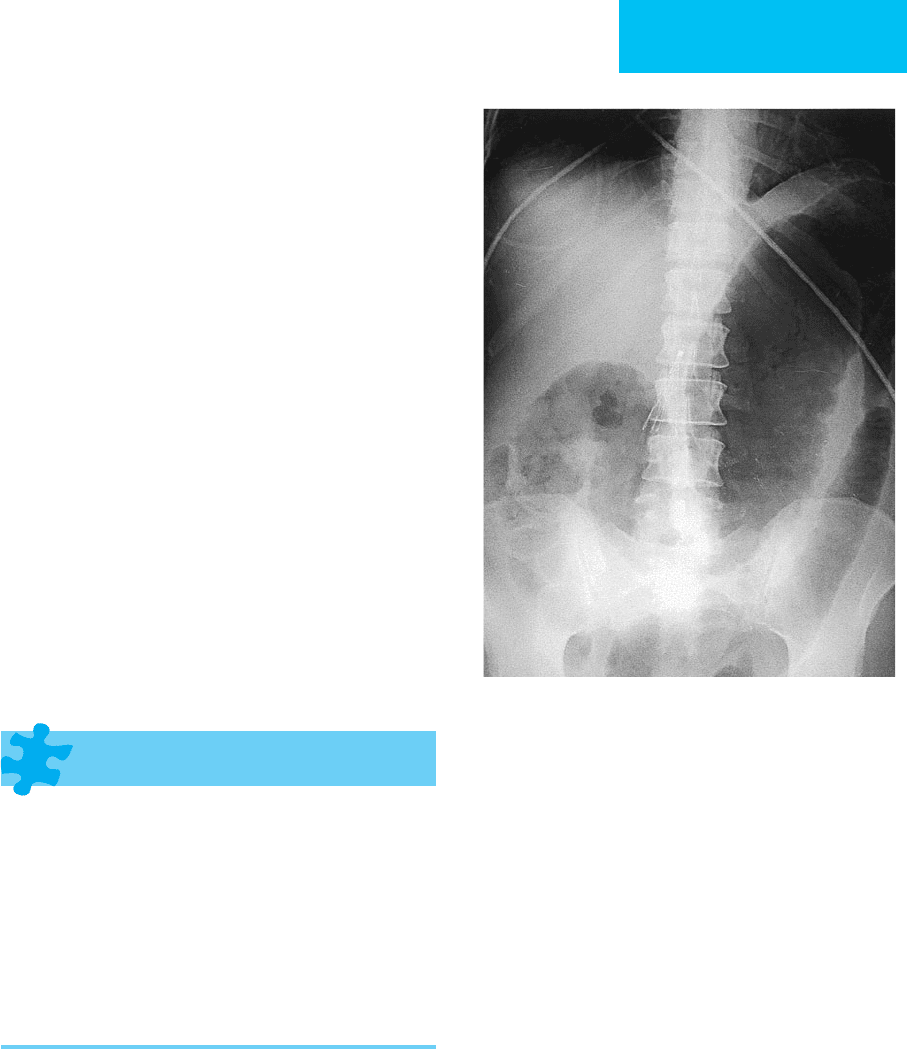

Generally, plain radiographs will reveal varying degrees of

colonic dilation (generally >6.5 cm) with or without associated

fold thickening. Thickened or effaced haustra are present, with

edematous or inflamed folds, and there is a paucity of feces. An

enema is contraindicated if toxic megacolon is suspected

(Figure 7–30). These features are more clearly seen on abdom-

inal CT imaging, and complications such as perforation and

gas within the colonic wall are easier to detect. The pericolonic

fat is usually infiltrated, and both colon and fat are sometimes

hyperemic.

Intraabdominal Abscess

ESSENTIALS OF RADIOLOGIC

DIAGNOSIS

Plain film: Usually invisible except when abscess is gas-

filled or produces a mass effect.

Ultrasound: Well-circumscribed collection of variably

echogenic fluid.

Abdominal CT: Well-circumscribed fluid-filled mass,

which may contain gas. Wall is of variable thickness and

enhancement.

Radionuclide scintigraphy: Radionuclide-tagged white

blood cell scan may be useful in search of occult abscess

or other sources of infection.

General Considerations

Over the past 25 years, imaging has revolutionized the diag-

nosis and management of abdominal and pelvic abscesses,

often precluding the need for laparotomy and for incision

and drainage in the vast majority of patients.

Intraabdominal abscesses typically are caused by perfo-

rated appendicitis in the young and diverticulitis in the

elderly. Overall, most cases are iatrogenic, occurring after

intraabdominal surgery. Hematogenous seeding of bacteria

may be responsible for liver and, especially, splenic abscesses.

The mortality remains high, ranging from 80% to 100% with-

out treatment and up to 30% in patients receiving appropri-

ate therapy.

Radiographic Features

A. Plain Radiographs—These may be helpful in evaluating

the gastrointestinal tract but are not generally able to localize

an abscess. On occasion, the abscess will appear as a gasless

fluid collection mimicking a mass with defined radiodense

contours that displaces bowel or bladder.

B. Ultrasound—Ultrasound is an excellent means for bed-

side evaluation of defined areas such as the upper quadrants,

Figure 7–30. Toxic megacolon. Plain radiograph demon-

strates diffuse dilation and severe thickening of mucosal folds

(thumbprinting) of the colon. There is no stool. The patient

was in extremis with a severe flare of ulcerative colitis.

CHAPTER 7

178

the paracolic gutters, and the pelvis. Features that suggest

an infected fluid accumulation on sonography include

rounded or ovoid collections with thick walls, with variable

internal echoes and without evidence of central vascularity,

as demonstrated by color, power, or spectral Doppler sig-

nals. Focal bright echoes with variable shadowing within

collections may suggest the presence of gas. However, these

signs are not specific for infected fluid; a hematoma or

seroma may appear identical. On the other hand, nonin-

fected collections generally have angular margins, conform

to anatomic spaces, and tend to lack significant internal

echogenicity.

Ultrasound is especially valuable for evaluating the sub-

diaphragmatic regions or the low pelvis. However, one

should bear in mind its limitations. Ultrasound will not

reliably evaluate the retroperitoneum and retroperitoneal

organs such as the pancreatic body and tail. Evaluation of

complex collections in postoperative patients or in patients

with open abdominal incisions or surgical dressings is likely

to be suboptimal. Imaging of abscesses within organs may

be difficult.

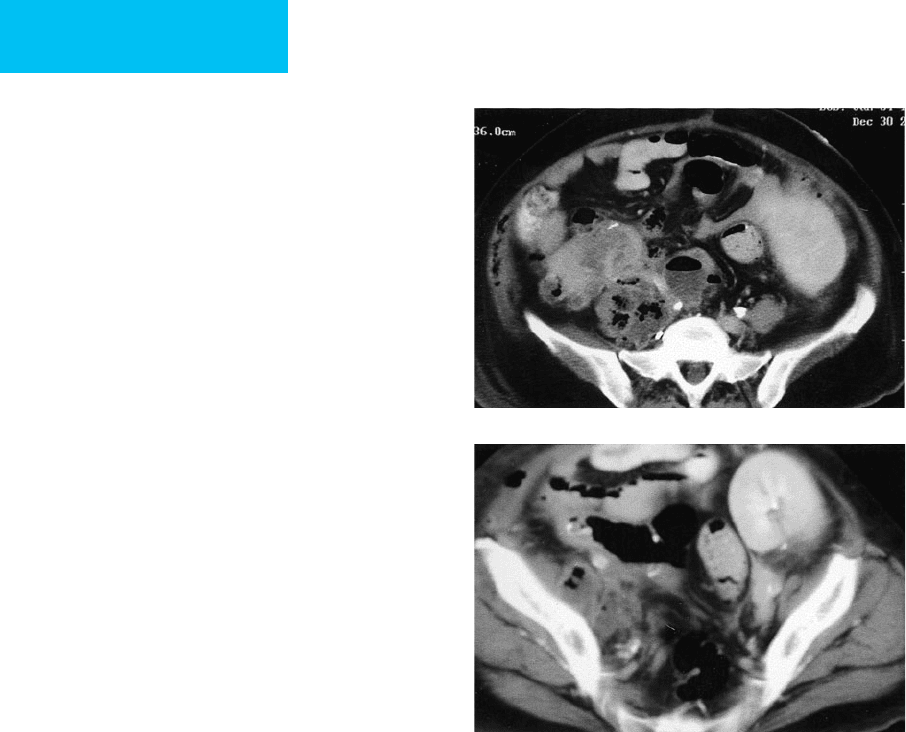

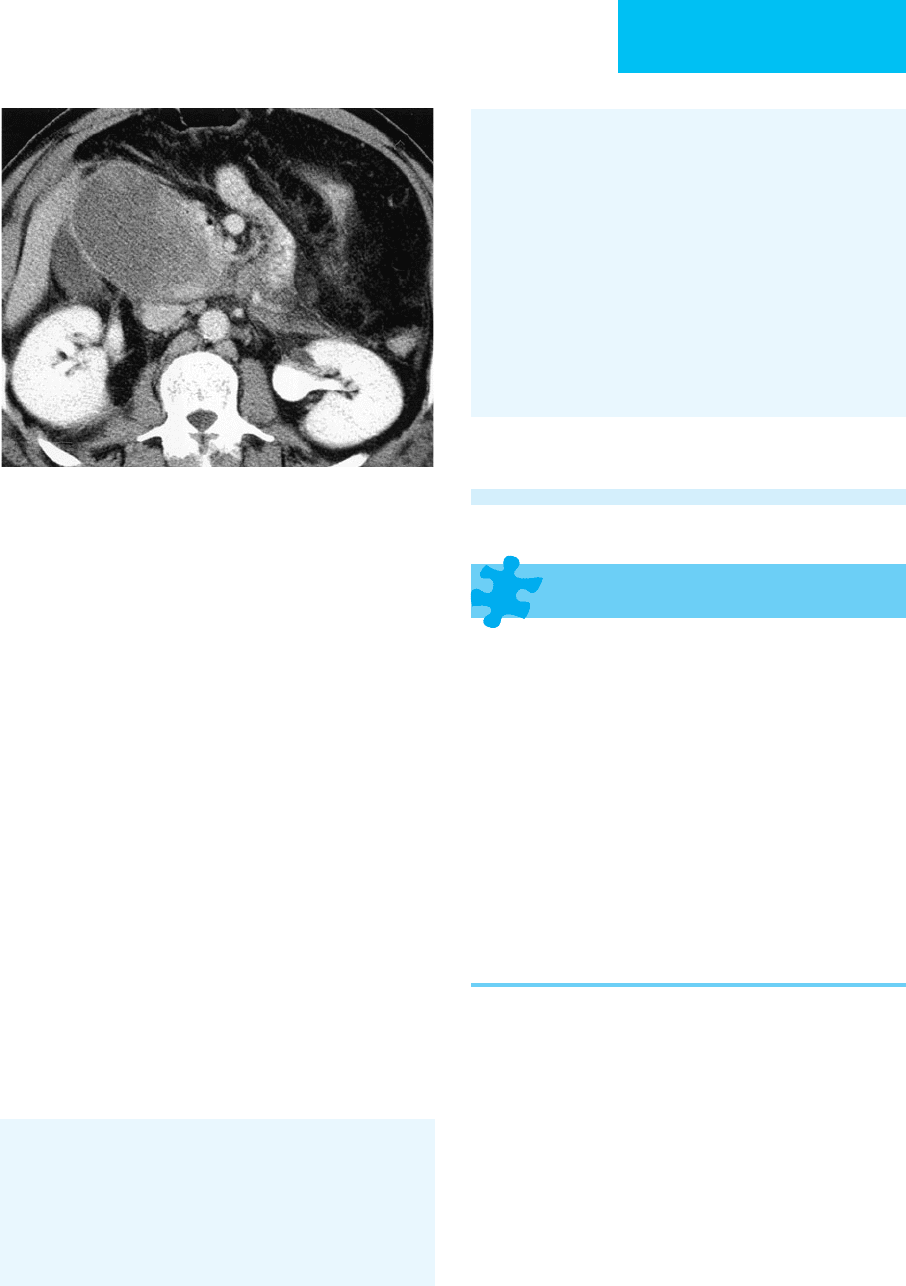

C. Computed Tomography—CT is the method of

choice for evaluation of an intraabdominal abscess

(Figure 7–31). Although preparation with oral and IV

contrast agents is preferred for optimal diagnosis in most

patients, contrast material is not always required when

using the latest-generation equipment. This is especially

true in obese patients because of inherent contrast pro-

vided by intraabdominal fat. Actual scanning time with a

multidetector helical scanner is typically on the order of

20–40 seconds.

Abscesses generally appear as round or ovoid collections

with thick surrounding rims. Intraluminal gas due to

anaerobic bacterial infection may be present in up to 50%

of collections. If IV contrast material is given, enhancement

of the surrounding rim may be noted in up to 50% of

abscesses. Abscesses under the diaphragm and surrounding

the liver or kidney may have crescentic margins. However,

in many cases, the CT signs of an abscess are nonspecific.

Necrotic tumors may have an identical appearance, and

percutaneous aspiration may be required to distinguish

between them.

D. Radionuclide Scintigraphy—Although unnecessary in

the vast majority of patients, nuclear medicine studies with

indium (

111

In)–labeled or gallium citrate (

67

Ga)–labeled

white blood cells are useful for the detection of occult

abscesses, especially in patients with fever of unknown origin.

Both indium oxine–labeled and gallium citrate–labeled cells

are injected intravenously, and scans are typically obtained

48–72 hours later. Although gallium is highly sensitive for

the detection of intraabdominal abscess (80–90%), speci-

ficity is limited by intestinal secretion at 48–72 hours.

Overall, indium-labeled white blood cell scans are more

accurate for abdominal applications.

E. Algorithm for Imaging the Patient with Suspected

Abdominal Abscess—In patients without localizing signs

or symptoms and varying degrees of suspicion of abdominal

abscess, the test of choice is helical or multidetector CT with

IV and oral contrast. This study helps to exclude potential

peritoneal and retroperitoneal sources of infection. CT is

necessary for adequate visualization of the pancreas, psoas

muscles, other retroperitoneal structures and complex col-

lections. CT is superior to other imaging methods in patients

A

B

Figure 7–31. Psoas abscess. Young woman with pain

and fever 1 month after renal and pancreas transplanta-

tion. A. CT demonstrates a multiloculated right psoas

abscess with air and gas tracking into the right psoas

sheath. B. Air in the right abdominal wall is from a

recent biopsy.

IMAGING PROCEDURES

179

with ileus, open incisions, dressings, indwelling catheters,

and drains. If symptoms are localized to the upper abdomi-

nal quadrants or to the pelvis, ultrasound is an excellent

choice for diagnosis and can be performed quickly at the

bedside. Furthermore, bedside percutaneous incision and

drainage may be performed with sonographic guidance.

Scintigraphy has a limited role in diagnosing abscess in an

acutely ill patient.

F. Percutaneous Image-Guided Drainage—Percutaneous

drainage has revolutionized the management of infected

fluid collections. Expanded criteria render only a small

minority of collections unsuitable for such drainage.

General criteria include a fluid collection at least 2–3 cm in

diameter and safe access to the collection without inter-

vening blood vessels, pleura, bladder, or bowel. One should

confirm with CT or sonographic Doppler that the collec-

tion in question is not a pseudoaneurysm. Fluid collections

may be multiloculated or communicate with the gastroin-

testinal, biliary, or genitourinary tracts. Solid organ and

tubo-ovarian abscesses may be drained safely, although the

latter frequently respond to antibiotics and needle aspira-

tion alone.

A number of catheter types and sizes are available.

Noninfected serous collections usually can be drained with

6–8F catheters, whereas infected, thick purulent collections

may be drained with 10–14F catheters. Multiple catheters or

larger catheters (16–18F) occasionally may be needed for

multiloculated noncommunicating thick-walled collections.

Guidance for drainage procedures includes ultrasound, fluo-

roscopy, or CT. Ultrasound is especially versatile because cav-

itary probes (endovaginal or endorectal) can help diagnose

deep pelvic abscesses and guide transrectal or transvaginal

drainage. Catheters should be left to gravity drainage and

flushed gently with 5 mL of normal saline at 8-hour intervals

to ensure patency. Drainage output should be recorded on

the nursing flow sheet.

Catheter position may be confirmed by fluoroscopic

injection of contrast material or by ultrasound or CT.

General criteria for catheter removal include resolution of

symptoms and signs, decrease in net catheter output to

under 10 mL/day, and closure of the cavity as determined by

follow-up imaging studies.

Gerzof SG et al: Percutaneous catheter drainage of abdominal

abscesses: A five year experience. N Engl J Med 1981;305:653–7.

[PMID: 7266601]

Gerzof SG et al: Expanded criteria for percutaneous abscess

drainage. Arch Surg 1985;120:227–32. [PMID: 3977590]

VanSonnenberg E et al: Percutaneous abscess drainage: Update.

World J Surg 2001;25:362. [PMID: 11343195]

Yu SC et al: Treatment of pyogenic liver abscess: Prospective, ran-

domized comparison of catheter drainage and needle aspira-

tion. Hepatology 2004;39:932–8. [PMID: 15057896]

Acute Pancreatitis

ESSENTIALS OF RADIOLOGIC

DIAGNOSIS

Plain radiographs: Gallstones, ileus of regional bowel (sen-

tinel loop), transverse colon ileus (colon cutoff), pancreatic

calcifications (chronic pancreatitis), and pleural effusion.

Ultrasound: Peripancreatic fluid, enlarged pancreas with

variable echogenicity, localized fluid collections,

cholelithiasis, choledocholithiasis, biliary tract obstruction.

Helical CT: Pancreatic enlargement, necrosis, or hemor-

rhage; thoracic and intraabdominal fluid or fluid collec-

tions; cholelithiasis; choledocholithiasis.

General Considerations

Imaging studies in acute pancreatitis help to confirm the

diagnosis, suggest possible causes (eg, choledocholithiasis or

pancreas divisum), detect features suggesting chronicity, and

demonstrate the extent of complications, such as abscess,

pseudocyst, hemorrhage, and necrosis. Imaging findings may

add to prognostic information derived from clinical and

serum laboratory parameters.

Acute pancreatitis is caused mainly by alcohol abuse or

choledocholithiasis. In the ICU, iatrogenic causes such as

postoperative state, medications (eg, antiretrovirals,

chemotherapeutic agents), or endoscopic retrograde cholan-

giopancreatography may cause acute pancreatitis. Other

causes include trauma, hypercalcemia, hypertriglyceridemia,

peptic ulcer disease, and structural congenital anomalies.

By imaging criteria, acute pancreatitis may be subdivided

broadly into acute interstitial (edematous) pancreatitis and

acute necrotizing or hemorrhagic pancreatitis. While acute

interstitial pancreatitis is usually self-limited and requires

supportive care, acute necrotizing pancreatitis is difficult to

manage and carries a significant risk of high morbidity and

mortality. In up to 60% of patients, peripancreatic and pan-

creatic fluid collections are present. Pseudocysts, which are

collections of pancreatic juice and debris, are lined by a

fibrous capsule and by definition have been present for at

least 4 weeks. In the acute phase, the behavior of a phlegmon

or nonliquified inflammatory pancreatic tissue is difficult to

predict, although most resolve. If a pancreatic abscess is

detected, prompt percutaneous or surgical debridement must

be performed because it is associated with a high mortality.

Radiographic Features

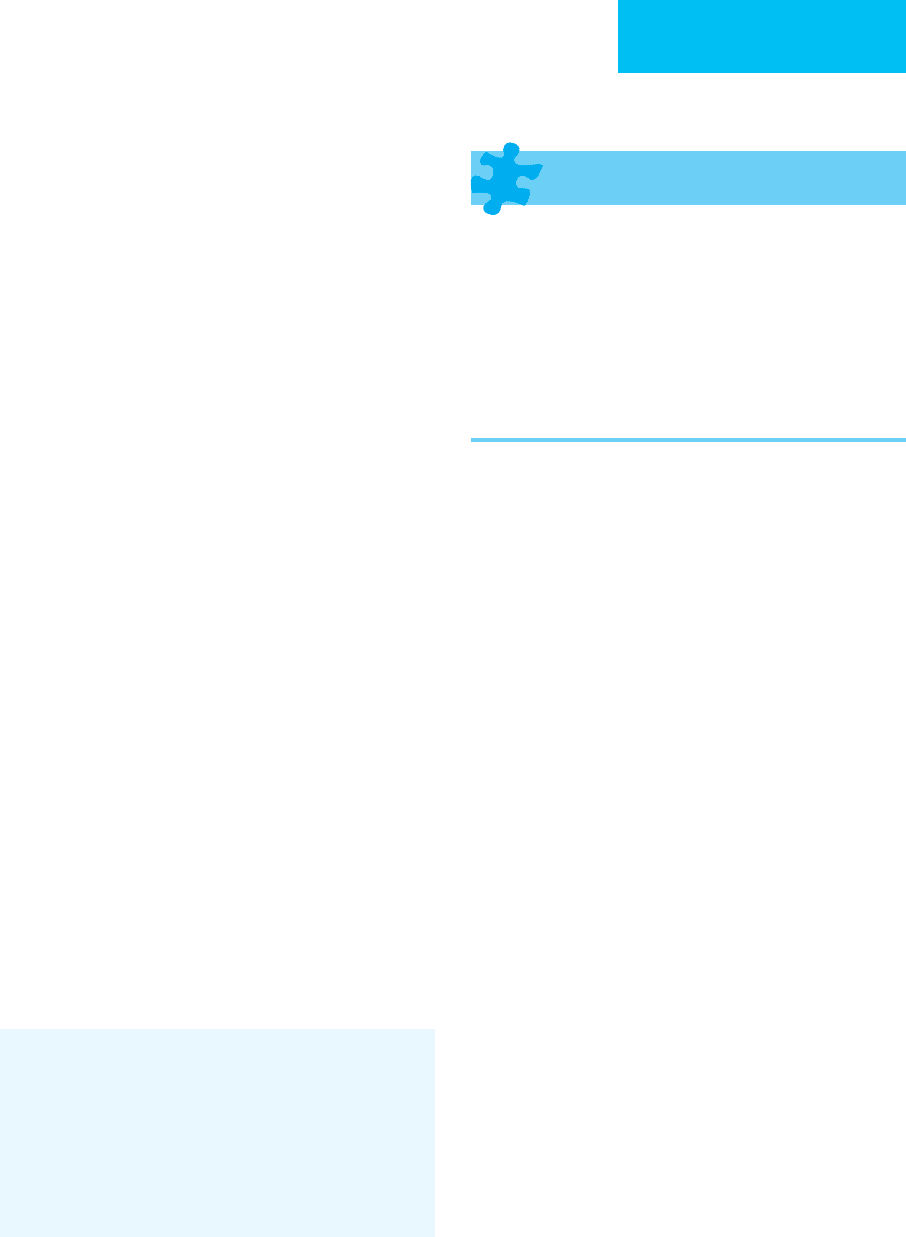

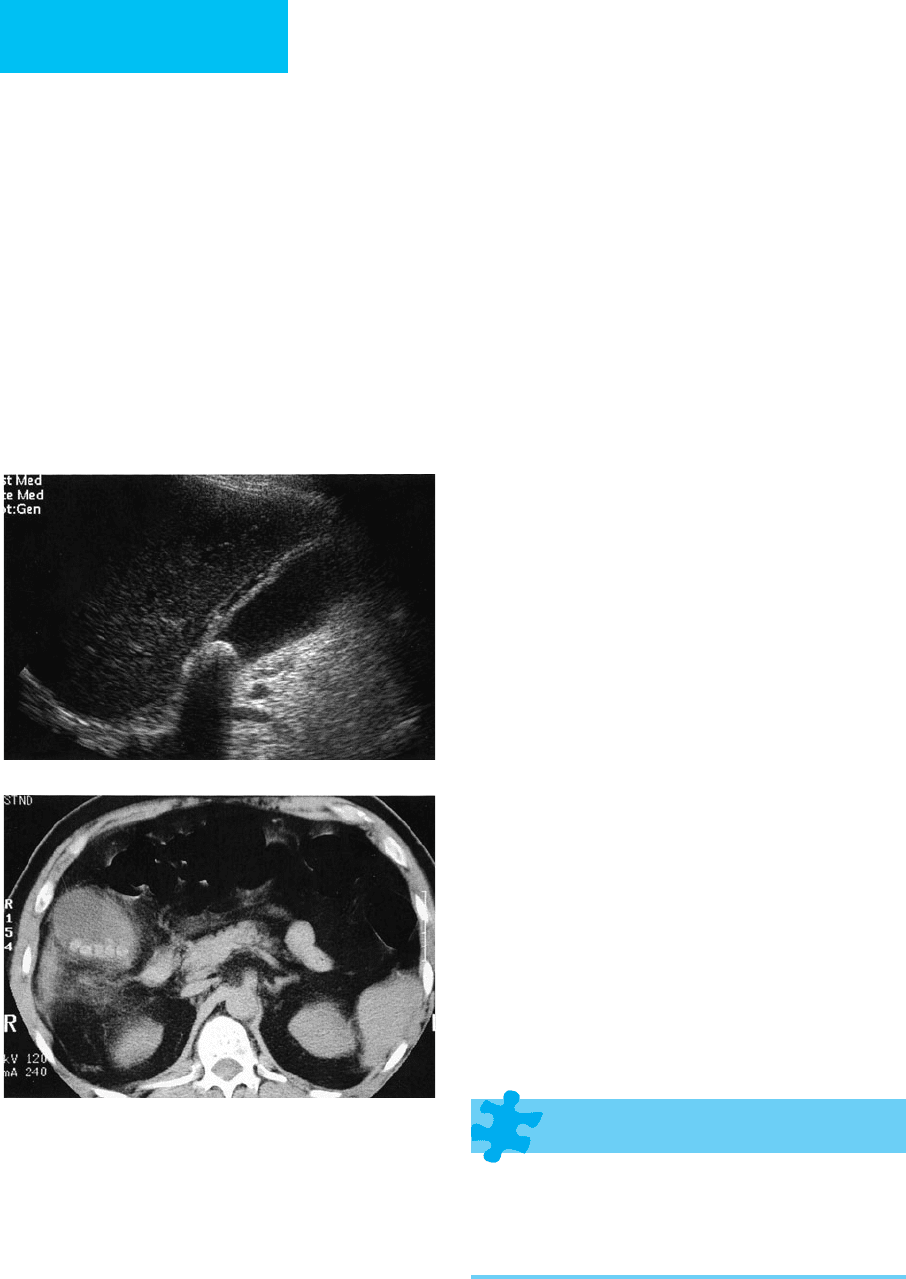

A. Plain Abdominal Radiographs—Several indirect signs in a

patient with acute back or epigastric pain suggest acute

pancreatitis (Figure 7–32). However, none of the following are

CHAPTER 7

180

specific for pancreatitis: (1) duodenal ileus—gas in the second

portion of the duodenum—reported in up to 50% of patients,

(2) jejunal ileus—focal gaseous distention of a jejunal loop

(“sentinel-loop sign”), (3) transverse colon ileus—gaseous dis-

tention of the transverse colon with a paucity of gas in the

descending colon—compatible with the “colon cutoff sign,” and

(4) left-sided pleural effusion, reported in 10–15% of patients.

B. Fluoroscopic Contrast Studies—Upper gastrointestinal

studies may be indicated to look for peptic ulcer disease.

Although they are not indicated for the diagnosis of acute

pancreatitis, one sometimes may observe a widening of the C-

loop with thickening of the duodenal folds due to edema.

C. Ultrasound—An ultrasound examination may be neces-

sary to confirm or exclude the presence of gallstones within

the gallbladder or common duct. Sonographic imaging of

the pancreas may reveal diffuse edema.

D. Abdominal CT—Current CT techniques allow detailed

pancreatic imaging tailored to the particular clinical situation.

In the setting of acute pancreatitis, a single or multidetector

helical CT may be performed, imaging the pancreas with a

minimum of 3-mm collimation with IV contrast enhance-

ment in the “pancreatic phase,” approximately 40 seconds

after bolus contrast material injection in patients with normal

cardiac output. In addition to highly detailed pancreatic

images, the remainder of the abdomen and pelvis should be

imaged to exclude distant complications, including fluid col-

lections and phlebitis. CT is the single best imaging method

for pancreatic evaluation because it provides excellent evalua-

tion and the ability to treat complications percutaneously.

Uncomplicated acute pancreatitis has an extremely vari-

able presentation. The pancreas may be normal or edema-

tous, increasing the attenuation of the intrapancreatic fat. The

peripancreatic fat planes may become infiltrated by edema

and products of the nonspecific inflammatory response. In

patients with severe pancreatitis, sections of the gland

undergo necrosis and may become hemorrhagic or infected.

On CT, lack of diffuse and homogeneous pancreatic enhance-

ment with IV contrast material reflects poor parenchymal

perfusion and is typical of necrotizing pancreatitis. In areas of

necrosis, the pancreas becomes ill-defined, with a severe peri-

pancreatic inflammatory response and local and distant free

and contained fluid. Splenic vein thrombosis may be present,

and other complications such as pseudoaneurysm formation

and pseudocyst formation may be seen at local and distant

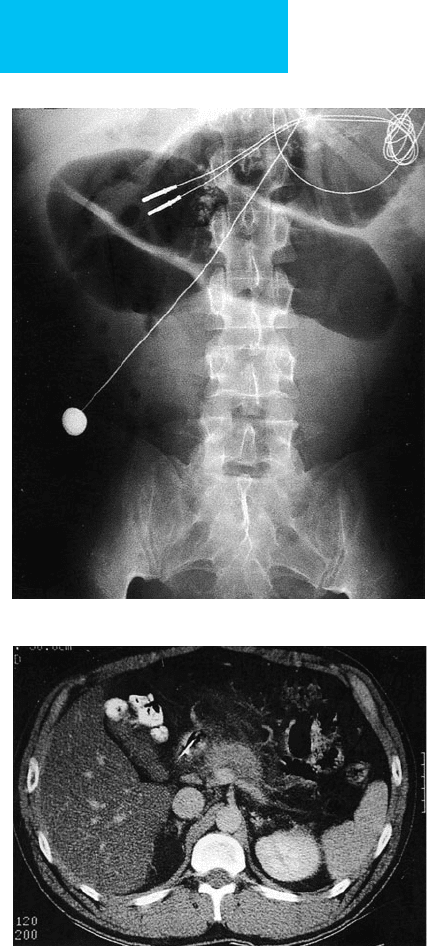

sites (Figure 7–33). A proposed CT grading system is used in

some centers to estimate the amount of pancreatic injury and

to predict outcome. Hemorrhagic complications are well seen

because recent hemorrhage (<1 week) is usually of high

attenuation compared with surrounding tissue. Over time as

the hematoma ages, its attenuation gradually decreases.

A pancreatic abscess, which may complicate acute pancre-

atitis in up to 9% of patients, implies a poor prognosis, with

reported mortality rates of 40–70% in the pre-CT era. Prompt

CT diagnosis and treatment have reduced the mortality rate to

20%. CT appearance of a pancreatic abscess can be variable

and can range from a contained fluid collection to a more typ-

ical rim-enhancing lesion with central low attenuation and gas

collection. The latter findings are present in only 20–30% of all

pancreatic abscesses, and percutaneous aspiration is usually

necessary for confirmation. The presence of gas bubbles also

may suggest a fistulous communication with bowel.

Figure 7–32. Acute pancreatitis. A. Plain film demon-

strates focal dilated “sentinel loops” resulting from localized

ileus. B. Abdominal CT in the same patient shows peripan-

creatic stranding and a fatty liver from recent ethanol abuse.

A

B

IMAGING PROCEDURES

181

Treatment

Acute pancreatitis complicated by necrosis or infection often

can be treated successfully by aggressive percutaneous catheter

drainage with large-bore catheters. In more complex or severe

cases, percutaneous management may help to temporize a

critically ill patient until surgical debridement is possible.

The management of pseudocysts is complex. Generally,

pseudocysts may be managed expectantly because most will

regress over time. By definition, a true pseudocyst has a

mature fibrous wall developed over at least 4 weeks.

Indications for percutaneous drainage or internal drainage

into the stomach are the following: infection; enlargement;

pain; bowel, bile, or urinary obstruction; and diameter greater

than 5 cm. For noninfected pseudocysts, success rates for

internal or external drainage are high. For the 20–30% of

pseudocysts communicating with the pancreatic duct, external

drainage will be difficult, and a cyst gastrostomy performed

percutaneously, surgically, or laparoscopically may be better.

Superinfection of a previously sterile pseudocyst occurs

in less than 5% of cases. As with most fluid collections, iden-

tification of infection within a pseudocyst requires clinical

suspicion and confirmation by percutaneous aspiration.

Successful drainage of an infected pseudocyst uses the same

principles of drain placement and management as for most

intraabdominal abscesses.

Arvanitakis M et al: Computed tomography and magnetic reso-

nance imaging in the assessment of acute pancreatitis.

Gastroenterology 2004;126:715–23. [PMID: 14988825]

Balthazar EJ: Acute pancreatitis: Assessment of severity with clinical

and CT evaluation. Radiology 2002;223:603–13. [PMID: 12034923]

Casas JD et al: Prognostic value of CT in the early assessment of

patients with acute pancreatitis. AJR 2004;182:569–74. [PMID:

14975947]

Kwon RS, Scheiman JM: New advances in pancreatic imaging.

Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2006;22:512–9. [PMID: 16891882]

Memis A, Parildar M: Interventional radiological treatment in

complications of pancreatitis. Eur J Radiol 2002;43:219–28.

[PMID: 12204404]

Maher MM et al: Acute pancreatitis: The role of imaging and inter-

ventional radiology. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2004;27:208–25.

[PMID: 15024494]

Miller FH et al: MRI of pancreatitis and its complications: 1. Acute

pancreatitis. AJR 2004;183:1637–44. [PMID: 15547203]

Nichols MT et al: Pancreatic imaging: Current and emerging tech-

nologies. Pancreas 2006;33:211–20. [PMID: 17003640]

Shankar S et al: Imaging and percutaneous management of acute

complicated pancreatitis. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol

2004;27:567–80. [PMID: 15578132]

IMAGING OF ACUTE GALLBLADDER & BILIARY

TRACT DISORDERS

Acute Calculous Cholecystitis

ESSENTIALS OF RADIOLOGIC

DIAGNOSIS

Plain films: 15–20% of gallstones are radiopaque; dis-

tended gallbladder may be present in the right abdomen

and produce a rounded radiodensity; gas may be present

in the lumen or wall in emphysematous cholecystitis.

Ultrasound: Thickening of gallbladder wall (>3 mm),

intraluminal gallstones and sludge, pericholecystic

fluid and focal tenderness over gallbladder (sono-

graphic Murphy’s sign).

CT: Nearly 100% of gallstones visualized. Distended

gallbladder with thickened wall, rim enhancement,

pericholecystic fat stranding, gas in lumen or wall in

emphysematous cholecystitis.

Hepatobiliary scintigraphy: Uptake of iminodiacetic acid

analogues into liver but nonvisualization of gallbladder

within 60 minutes of injection.

General Considerations

In acute calculous cholecystitis, cystic duct obstruction

results from a lodged gallstone in almost 95% of cases. The

gallbladder distends, with resulting mucosal inflammation

and edema from bile stasis. Both distention and mural edema

may lead to venous obstruction and subsequent mural

ischemia and possible perforation.

Clinical parameters are of limited utility in the critical

care setting. There is a significant clinical overlap among a

variety of conditions, such as acute pancreatitis, perforated

peptic ulcer, pyelonephritis, and thoracic abnormalities such

as pneumonia and myocardial infarction.

Figure 7–33. Complicated pancreatitis. CT demon-

strates a large pseudocyst in the head of the pancreas.

CHAPTER 7

182

Radiographic Features

A. Plain Abdominal Radiographs—Plain radiographs can

detect the 15% of gallstones that are radiopaque. In emphy-

sematous cholecystitis, typically seen in diabetics, gas within

the gallbladder wall and lumen may be seen. Plain films also

may be useful to distinguish other causes of right upper

quadrant pain, such as a perforated viscus or pneumonia.

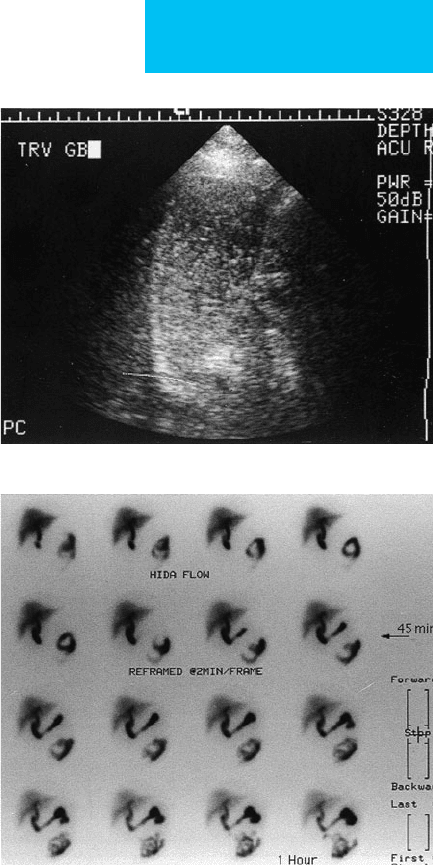

B. Ultrasound—Ultrasound should be the test of choice for

rapid diagnosis of acute cholecystitis at the bedside. Features

highly suggestive of acute calculous cholecystitis include a

thick-walled, distended gallbladder with gallstones, perichole-

cystic fluid, and focal tenderness overlying the gallbladder

(sonographic Murphy’s sign)(Figure 7–34). However, in

patients who have been in the ICU for a few days or longer,

the gallbladder tends to look abnormal on sonography, usu-

ally having a thickened wall and internal echoes. In these

patients, a reliable sonographic Murphy’s sign should be

absent. Sonography also may be limited by body habitus,

overlying bowel gas, gangrenous cholecystitis, or overlying

dressings. Pericholecystic fluid is an unreliable sign in patients

with ascites. Gallbladder wall thickening alone in the absence

of other findings may have many causes, including acute hep-

atitis, HIV cholangiopathy, IL-2 therapy, and anasarca.

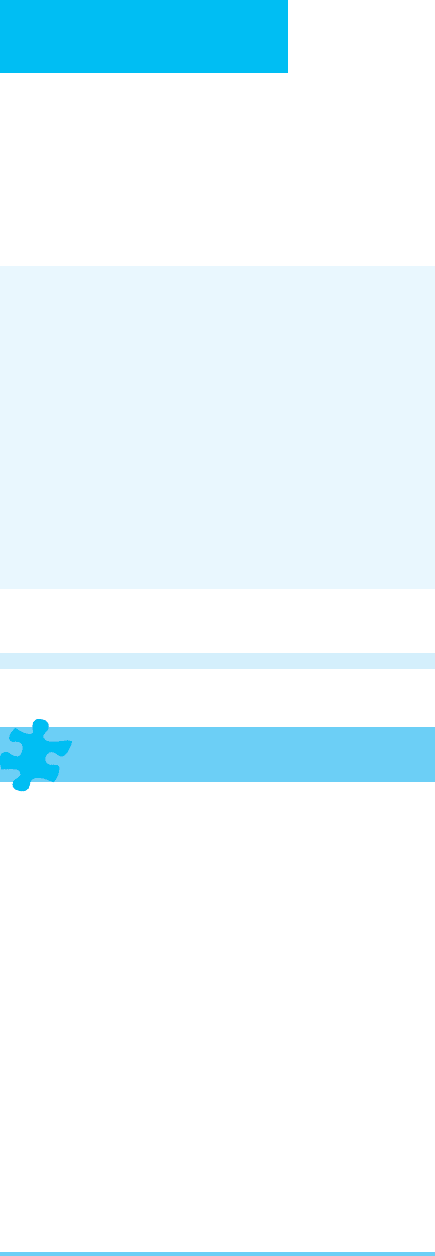

C. Scintigraphy—In patients with equivocal signs and

sonography, scintigraphy may provide complementary infor-

mation in acute calculous cholecystitis. Technetium (

99m

Tc)

iminodiacetic acid–derived agents have been shown to have

high sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of acute

cholecystitis. These agents are injected intravenously, and

sequential imaging is performed over the liver with a SPECT

camera. Sequential liver uptake and excretion into the biliary

tree and intestine are imaged for up to 1 hour after injection.

Normally, the gallbladder should fill with the radiotracer

within 1 hour. Lack of filling confirms the diagnosis of acute

calculous cholecystitis. However, lack of filling is also seen

with intrinsic gallbladder dysfunction.

Although scintigraphy is an excellent test, it is cumber-

some to perform at the bedside in the ICU compared with

sonography. An accurate test requires that the patient fast

for at least 2–4 hours prior to the procedure, and delayed

images up to 4 hours may be needed. Scintigraphy has high

negative predictive value; filling of the gallbladder within

1 hour excludes the diagnosis of acute calculous cholecystitis.

However, many causes can prevent radiotracer flow into the

cystic duct, and false-positive examinations have been

reported in up to 40% of severely ill or debilitated patients.

The most common causes of false-positive tests are bile sta-

sis, bile hyperviscosity, and gallbladder distention. Specific

causes include chronic cholecystitis, hyperalimentation,

severe jaundice, hepatic dysfunction, pancreatitis, prolonged

fasting, and recent nonfasting state. Causes of false-negative

tests include pancreatitis and poor hepatic function.

Hepatobiliary scintigraphic agents also may be used to con-

firm complications such as total common duct obstruction

or bile leak.

Acalculous Cholecystitis

ESSENTIALS OF RADIOLOGIC

DIAGNOSIS

Ultrasound: Gallbladder wall is thickened; no intralumi-

nal stones; sonographic Murphy’s sign usually present.

CT: Mural thickening and inflammatory infiltration of

the pericholecystic fat.

A

B

Figure 7–34. Acute cholecystitis. A. Ultrasound demon-

strates a stone at the gallbladder neck with thickening of

the gallbladder wall, pericholecystic fluid, and tenderness

on compression (sonographic Murphy’s sign). In combination,

these features are highly specific for acute cholecystitis. B. In

another patient, abdominal CT shows distended gallbladder

with gallstones and surrounding infiltration of the fat.

IMAGING PROCEDURES

183

General Considerations

Acalculous cholecystitis is associated with a variety of clinical

conditions, including chronic debilitation, prolonged intuba-

tion, nasogastric suction and hyperalimentation, burns, and

pancreatitis. Although comprising 10–15% of all cases of chole-

cystitis, acalculous cholecystitis predominates in the postopera-

tive and posttraumatic patient population, accounting for up to

90% of all cholecystitis cases seen in that group. Mechanisms are

poorly understood and probably multifactorial. Bile stasis, bile

hyperconcentration, and edema with pressure in the gallbladder

wall leading to progressive ischemia have been linked to the

pathogenesis of this disorder. In addition, reflux of pancreatic

juices through biliary enteric anastomoses and pancreatitis have

been suggested. The clinical presentation of acalculous chole-

cystitis is similar to that of calculous cholecystitis. However, typ-

ical symptoms may be masked by concomitant problems.

Radiographic Features

As with the clinical diagnosis, the radiologic diagnosis is also

difficult. In the patient population most prone to acalculous

cholecystitis, intrinsic functional and morphologic abnor-

malities of the gallbladder limit the specificity of both scintig-

raphy and sonography (Figure 7–35). Scintigraphy relies on

technetium (

99m

Tc) iminodiacetic acid to fill the gallbladder,

and scans often are done with pharmacologic intervention to

improve accuracy. Morphine may cause contraction of the

sphincter of Oddi, resulting in increased back pressure; chole-

cystokinin can be used to first empty the gallbladder. Although

the sensitivity of scintigraphy has been reported to be as high

as 95%, specificity is significantly lower than in calculous

cholecystitis. This is so because of the high number of false neg-

atives resulting from coexisting conditions such as prolonged

intubation, nasogastric suction, and hyperalimentation.

Sonographic features suggesting cholecystitis are simi-

larly compromised in these patients. They may have mild

wall thickening from edema and mild contraction. Often,

right upper quadrant tenderness mimicking a sonographic

Murphy sign is present in these patients in the absence of

acalculous cholecystitis. Although the sensitivity of sonogra-

phy is high, specificity is poor.

If results are equivocal, both scintigraphy and ultrasound

may be necessary, or a CT scan may be performed. Using IV

contrast–enhanced CT, mural thickening, mucosal enhance-

ment, and subtle pericholecystic inflammatory changes may

improve specificity.

Treatment

In patients with uncomplicated acute cholecystitis, IV antibi-

otics contain the inflammatory response and suppress further

inflammation, allowing patients to undergo less invasive surgery

with fewer complications. Although percutaneous aspiration

usually can be performed in patients with acute cholecystitis, its

role is debated because there is a high incidence of false-negative

sterile aspirates resulting from effective antibiotic treatment.

Temporary gallbladder decompression by percutaneous

cholecystostomy is beneficial in patients with acute cholecys-

titis who are at high surgical risk. The procedure is performed

with sonographic and fluoroscopic guidance in most institu-

tions, but it may be performed with CT guidance. It also can

be performed with sonographic guidance alone at the bed-

side. Complications, including bile leak, hemobilia, and vagal

reaction, have been reported in 5–10% of patients—less than

the complication rate associated with surgery (24%). Other

A

B

Figure 7–35. Acalculous cholecystitis. A. Ultrasound

demonstrates diffuse echoes throughout the gallbladder,

a marginally thickened wall, and positive sonographic

Murphy’s sign. B. HIDA (hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid)

scan. The gallbladder does not fill with tracer by 60 minutes

despite provocative maneuvers.

CHAPTER 7

184

indications for percutaneous drainage include decompres-

sion of the biliary tract in cases of distal common duct

obstruction with only mild dilation of the intrahepatic ducts.

Some have advocated performing percutaneous cholecys-

tostomy in critically ill patients as a means of diagnosing and

treating acute cholecystitis. With this approach, in one study,

58% of critically ill patients improved.

Akhan O, Akinci D, Ozmen MN: Percutaneous cholecystostomy.

Eur J Radiol 2002;43:229–36. [PMID: 12204405]

Bennett GL, Balthazar EJ: Ultrasound and CT evaluation of emer-

gent gallbladder pathology. Radiol Clin North Am

2003;41:1203–16. [PMID: 14661666]

Bortoff GA et al: Gallbladder stones: Imaging and intervention.

Radiographics 2000;20:751–66. [PMID: 10835126]

Mariat G et al: Contribution of ultrasonography and cholescintig-

raphy to the diagnosis of acute acalculous cholecystitis in inten-

sive care unit patients. Intensive Care Med 2000;26:1658–63.

[PMID: 11193273]

Menu Y, Vuillerme MP: Non-traumatic abdominal emergencies:

Imaging and intervention in acute biliary conditions. Eur

Radiol 2002;12:2397–406. [PMID: 12271380]

Ziessman HA: Acute cholecystitis, biliary obstruction, and biliary

leakage. Semin Nucl Med 2003;33:279–96. [PMID: 14625840]

IMAGING IN EMERGENT & URGENT

GENITOURINARY CONDITIONS

Acute Renal Failure

ESSENTIALS OF RADIOLOGIC

DIAGNOSIS

Ultrasound: In obstructive uropathy, dilation of the calices

and renal pelvis with visualization of echogenic calculi; in

intrinsic renal disease, increased cortical echogenicity

correlates with chronic medical renal disease.

CT: In obstructive uropathy, signs of acute obstruction

on CT include dilation of the collecting system, a source

of obstruction such as stone, swollen kidney with

increased stranding in the perinephric space; CT urogra-

phy (noncontrast helical CT) provides a rapid method of

detecting renal calculi and obstructive nephropathy

from a passing stone.

MR urography: Rapid assessment of cause and level of

obstruction; with gadolinium enhancement, differential

rates of enhancement permit assessment of renal

perfusion.

Renal scintigraphy: Technetium-99m MAG 3 scan per-

mits rapid assessment of differential renal function,

including flow, uptake, and excretion. Especially valuable

in transplanted kidneys to assess for a vascular occlusion

from intrinsic renal abnormality.

General Considerations

The workup of acute renal failure traditionally has been

focused on identifying prerenal, intrinsic renal, and postre-

nal causes. Prerenal causes (eg, cardiac or liver failure) and

systemic hypotension account for 75% of all causes of renal

failure. Intrinsic causes such as acute tubular necrosis and

glomerulonephritis account for 20%, and postrenal causes

such as obstructive nephropathy account for less than 5% of

cases. Imaging is used mainly to exclude an obstructive cause

of acute renal failure. These causes include obstruction from

a lower urinary tract source such as bladder tumor, prostatic

enlargement, or urethral stricture. Concomitant reflux also

may decrease renal function. Ureteral causes of obstruction

include luminal stones, tumors, blood clots, fungus balls, and

sloughed papillae, as well as extraluminal causes such as

mural strictures or extramural causes such as retroperitoneal

fibrosis, lymphadenopathy, or inadvertent ureteral ligation.

Radiographic Features

Azotemia due to obstruction is usually easily and rapidly

treatable. Cross-sectional imaging allows rapid identification

of hydronephrosis and its causes, as well as clues to evaluate

pyonephrosis, pyelonephritis, or abscess.

Sonography is the imaging method of choice to evaluate

hydronephrosis in the critically ill patient. It may be per-

formed at the bedside. Since it detects the presence of a

dilated collecting system, pitfalls in interpretation may be

present. In acute hydronephrosis, sonography may be normal

in 50% of patients because dilation is suboptimal, especially

in the first 72 hours. In subacute situations, a ruptured calix

may decompress the collecting system, leading to a false-

negative diagnosis if perinephric fluid is minimal or absent. A

volume-depleted patient may also have poor distention of the

collecting system due to low urine output. Patients with

retroperitoneal fibrosis or neoplastic encasement of the

ureters may have only minimally distended collecting sys-

tems. Conversely, patients with vesicoureteral reflux, para-

pelvic cysts, or prior episodes of inflammation may receive a

false-positive diagnosis of hydronephrosis. Sonography may

suggest the diagnosis of pyonephrosis or renal bleeding by the

presence of echoes in the collecting system.

In a large series of patients with azotemia undergoing renal

sonography, hydronephrosis was detected in 29% of those

known to be at high risk (ie, pelvic malignancy, palpable

abdominal or pelvic mass, renal colic, known nephrolithiasis,

bladder outlet obstruction, recent pelvic surgery, or sepsis).

However, in patients without these risk factors, hydronephro-

sis was detected in only 1%. Sixty-five percent of patients in

the low-risk group had medical renal disease compared with

36% of high-risk patients. The simplicity and relatively low

cost of a sonogram must be weighed against a typically nega-

tive result in the vast majority of patients and the risk of miss-

ing an obstructive cause of renal failure.

IMAGING PROCEDURES

185

Helical noncontrast CT has emerged over the past few

years as the imaging procedure of choice for the evaluation

of renal colic (Figure 7–36). Helical CT detects over 99% of

all types of calculi—with the exception of the stones caused

by crystallization of the antiretroviral protease inhibitor

indinavir. Helical CT images stones not only in the renal col-

lecting system but also in the ureters, bladder, and posterior

urethra. CT also images the retroperitoneum and pelvis,

allowing detection of processes such as retroperitoneal fibro-

sis and lymphadenopathy. CT is excellent for the detection of

perirenal abscesses and abscesses in other areas of the

abdomen and pelvis.

When a potentially obstructing stone is found in the uri-

nary tract, the specific signs of obstruction include

hydronephrosis and hydroureter to the level of obstruction,

unilateral infiltration of perirenal and periureteral fat, and a

swollen kidney. Hydronephrosis may not be distinguishable

from pyonephrosis. However, high-density debris or, espe-

cially, gas within the collecting system suggests pyonephrosis.

MRI is emerging as a tool for evaluating urinary tract dis-

ease. However, it is currently impractical in critically ill

patients.

Urinary Tract Infection

ESSENTIALS OF RADIOLOGIC

DIAGNOSIS

Ultrasound: Usually normal in uncomplicated pyelonephri-

tis. However, the kidneys may be enlarged, with variable

echogenicity. Focal nephritis may appear as a solid renal

mass. A renal abscess appears as a complex cystic or

hypoechoic mass.

CT: Pyelonephritis is typically associated with nonspe-

cific findings. Kidneys may be enlarged, with peri-

nephric stranding. With IV contrast material, a striated

nephrogram may be seen with delayed function in

infected areas. Focal nephritis appears as an ill-

defined region of low attenuation in a lobar distribu-

tion. Renal abscesses are well-defined masses, often

with an enhancing rim, increased attenuation of the

adjacent perirenal fat, and thickening of the renal

fascia.

General Considerations

Pyelonephritis is typically a clinical diagnosis. Imaging is

helpful to detect complications of pyelonephritis or urosep-

sis or in patients who have failed to respond to standard

medical therapy. Complications of pyelonephritis include

pyonephrosis, renal or perirenal abscess, or other conditions

requiring surgical or percutaneous intervention.

A

B

C

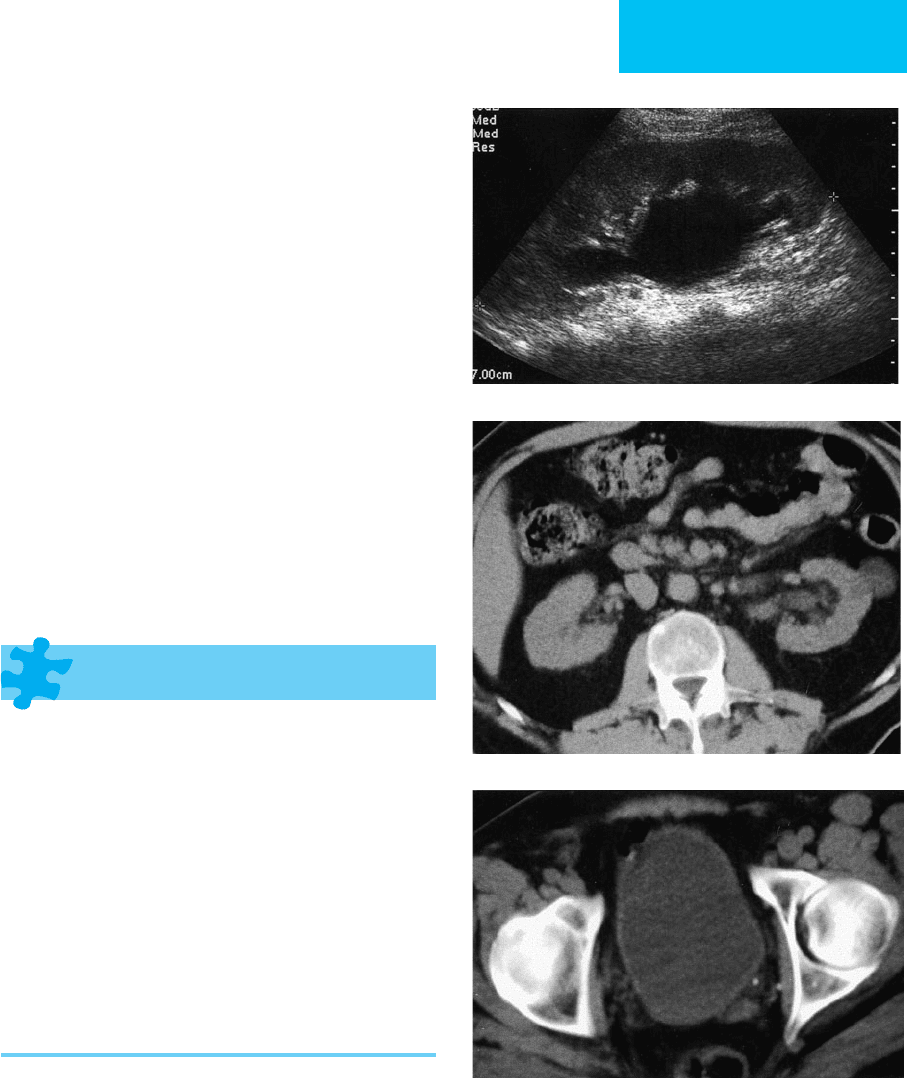

Figure 7–36. Obstructive uropathy. A. Ultrasound shows

moderate hydronephrosis of the left kidney. B. CT scan

demonstrates moderate left hydronephrosis with

hydroureter. C. There is a tiny calculus obstructing the left

ureterovesical junction.

CHAPTER 7

186

Radiographic Features

Sonography is relatively insensitive and nonspecific in diag-

nosing acute pyelonephritis. It is useful to exclude

hydronephrosis and possibly pyonephrosis, as well as renal or

perirenal abscess. However, sonography cannot diagnose

changes in the perinephric fat or inflammatory thickening of

the perirenal fascia.

Barrozzi L et al: Renal ultrasonography in critically ill patients. Crit

Care Med 2007;35:S198–205. [PMID: 17446779]

Colistro R et al: Unenhanced helical CT in the investigation of

acute flank pain. Clin Radiol 2002;57:435–41. [PMID:

12069457]

Dalrymple NC et al: Pearls and pitfalls in the diagnosis of

ureterolithiasis with unenhanced helical CT. Radiographics

2000;20:439–47. [PMID: 10715342]

Demertzis J, Menias CO: State of the art: Imaging of renal infec-

tions. Emerg Radiol 2007;14:13–22. [PMID: 17318482]

Noble VE, Brown DF: Renal ultrasound. Emerg Med Clin North

Am 2004;22:641–59. [PMID: 15301843]

Rao PN: Imaging for kidney stones. World J Urol 2004;22:323–7.

[PMID: 15290203]

Sandhu C, Anson KM, Patel U: Urinary tract stones: I. Role of radi-

ological imaging in diagnosis and treatment planning. Clin

Radiol 2003;58:415–21. [PMID: 12788310]

Tamm EP et al: Evaluation of the patient with flank pain and pos-

sible ureteral calculus. Radiology 2003;228:319–29. [PMID:

12819343]