Bongard Frederic , Darryl Sue. Diagnosis and Treatment Critical Care

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

IMAGING PROCEDURES

167

pressure, in all but one of the patients barotrauma was noted

when peak airway pressure was greater than 40 cm H

2

O. Other

studies report an incidence of about 50% and suggest that

PEEP does contribute to the development of barotrauma.

Decreased compliance of the lungs in patients with ARDS

necessitates higher ventilatory pressures to maintain adequate

oxygenation, which results in an increased risk of barotrauma.

Pulmonary diseases that increase lung compliance also may

promote barotrauma because there is greater overdistention of

the lung.

Radiographic Features

Radiographic findings of pulmonary interstitial emphy-

sema include visualization of perivascular air along pul-

monary vessels seen on end (producing a perivascular

“halo”), linear radiolucencies radiating toward the hila,

irregular radiolucent mottling, parenchymal cysts (pneu-

matoceles), and linear or rounded collections of air along

the visceral pleural surface (subpleural air cysts).

Pulmonary interstitial emphysema may be difficult to

detect and to distinguish from air bronchograms.

Moreover, pulmonary interstitial emphysema is usually not

apparent radiographically unless present in conjunction

with pulmonary opacification.

Pneumomediastinum may be recognized radiographi-

cally by linear lucencies adjacent to the heart and aortic arch,

descending aorta, and great vessels. Visibility of the wall of a

main bronchus, air outlining the thymus, and air between

the parietal pleura and diaphragm also have been described.

Pneumomediastinum is usually easier to identify than pul-

monary interstitial emphysema and is often the first evidence

of barotrauma. Subsequent dissection of air from the medi-

astinum along fascial planes may result in subcutaneous

emphysema, with linear radiolucencies extending along tis-

sue planes in the chest wall and neck (see Figure 7–17). Less

often, dissection of air along the descending aorta into the

retroperitoneum will occur, with rare rupture into the

abdomen giving rise to pneumoperitoneum. In such

instances, clinical correlation is essential to exclude a perfo-

rated abdominal viscus. Early diagnosis of pulmonary inter-

stitial emphysema may alert clinicians to pneumothorax, a

potentially catastrophic consequence of barotrauma.

Although other manifestations of barotrauma are usually

self-limited, even a small pneumothorax may progress to

tension pneumothorax in critically ill patients, particularly

in patients being maintained with mechanical ventilators. As

previously discussed, pneumothorax in the supine patient

may be difficult to diagnose and must be considered or it will

be missed. Occasionally, tension pneumomediastinum may

occur, although this is usually of greater clinical likelihood in

pediatric patients. Concomitant pulmonary interstitial

emphysema will result in further respiratory embarrassment

secondary to compression of lung parenchyma by interstitial

air and decreases in both ventilation and perfusion.

Pneumopericardium arises infrequently secondary to

barotrauma but may progress to tension, in which there is

increased intrapericardial pressure and impairment in

venous return and cardiac function.

Kemper AC, Steinberg KP, Stern EJ: Pulmonary interstitial emphy-

sema: CT findings. AJR 1999;172:1642. [PMID: 10350307]

Trotman-Dickenson B: Radiology in the intensive care unit (part 2).

J Intensive Care Med 2003;18:239–52. [PMID: 15035758]

Webb WR, Higgins CB: Thoracic Imaging: Pulmonary and

Cardiovascular Radiology. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams &

Wilkins, 2005.

IMAGING OF THE ABDOMEN & PELVIS

General Principles

Imaging of the gastrointestinal tract generally should begin

with plain radiographs because these are readily obtained

and provide useful information regarding perforation,

bowel obstruction, and ileus. However, because the overall

sensitivity of plain radiographs remains low, further imag-

ing with CT may be necessary to confirm suspected pneu-

moperitoneum or intraabdominal abscess and to inspect

the features of the small and large bowel walls and sur-

rounding fat. Imaging of abdominal and pelvic solid

organs, including the gallbladder and urinary bladder,

should begin with ultrasound because it is nonionizing and

portable to the ICU.

Gastrointestinal Perforation

ESSENTIALS OF RADIOLOGIC

DIAGNOSIS

Lucency over the liver or abdomen.

Lucency under a hemidiaphragm on upright views.

“Double-wall sign.”

Visualization of the falciform ligament.

“Football sign.”

“Inverted-V sign.”

“Triangle sign.”

General Considerations

In the ICU, bowel perforation usually results from an upper

abdominal source, such as a penetrating gastric or duodenal

ulcer; a lower gastrointestinal tract source, such as diverticulitis

or toxic megacolon; or from complications of upper and

lower endoscopic procedures. Other causes of perforation

include severe intestinal inflammation, bowel obstruction,

bowel infarction, or neoplasm.

CHAPTER 7

168

Radiographic Features

An experienced abdominal radiologist may identify even small

amounts of free air on a supine abdominal radiograph, finding

small bubbles or generalized increased lucency over the abdomen,

right upper quadrant, or subhepatic space. Other signs include

the “double-wall sign” of Rigler, the “triangle sign,” the “football

sign,” or the falciform ligament sign (Figure 7–22). For less expe-

rienced readers, a second view must be added to the supine radi-

ograph to increase sensitivity. Most commonly, this is an upright

abdominal film in which air rises to outline the thin curvilinear

hemidiaphragm. However, to obtain this view properly is nearly

impossible in the ICU. Useful alternatives include the left lateral

decubitus view (where the patient maintained in the left-side-

down position for at least 5–10 minutes), allowing free air to rise

toward the right subphrenic space. A right lateral decubitus view

is usually nondiagnostic because of confusion arising from the

adjacent stomach bubble. In immobile patients, a cross-table lat-

eral view may be obtained, in which the patient remains supine,

but the x-ray beam is tangential to the anterior abdominal wall.

However, small amounts of free air may be missed on this view. If

plain films are equivocal and perforation is suspected, an abdom-

inal CT (Figure 7–23) offers an excellent means of detecting even

tiny amounts of free air and possibly localizing a source.

Differential Diagnosis

Pneumoperitoneum has a variety of causes and is not synony-

mous with bowel perforation, its most serious and surgically

urgent cause. In the ICU, the most common reason for pneu-

moperitoneum is probably the postoperative state.

Pneumoperitonem may persist for up to 14 days after surgery,

the amount of air decreasing progressively and never increasing

over time. Other forms of pneumoperitoneum requiring urgent

attention include peritonitis caused by gas forming microorgan-

isms. Benign causes include dissection of gas from the thoracic

cavity in patients with COPD receiving mechanical ventilation.

Bhalla S, Menias CO, Heiken JP: CT of acute abdominal aortic disor-

ders. Radiol Clin North Am 2003;41:1153–69. [PMID: 14661663]

Gore RM et al: Helical CT in the evaluation of the acute abdomen.

AJR 2000;174;901–13. [PMID: 10749221]

Grassi R et al: Gastro-duodenal perforations: Conventional plain

film, US and CT findings in 166 consecutive patients. Eur J

Radiol 2004;50:30–6. [PMID: 15093233]

Pinto A et al: Comparison between the site of multislice CT signs

of gastrointestinal perforation and the site of perforation

detected at surgery in forty perforated patients. Radiol Med

(Torino) 2004;108:208–17. [PMID: 15343135]

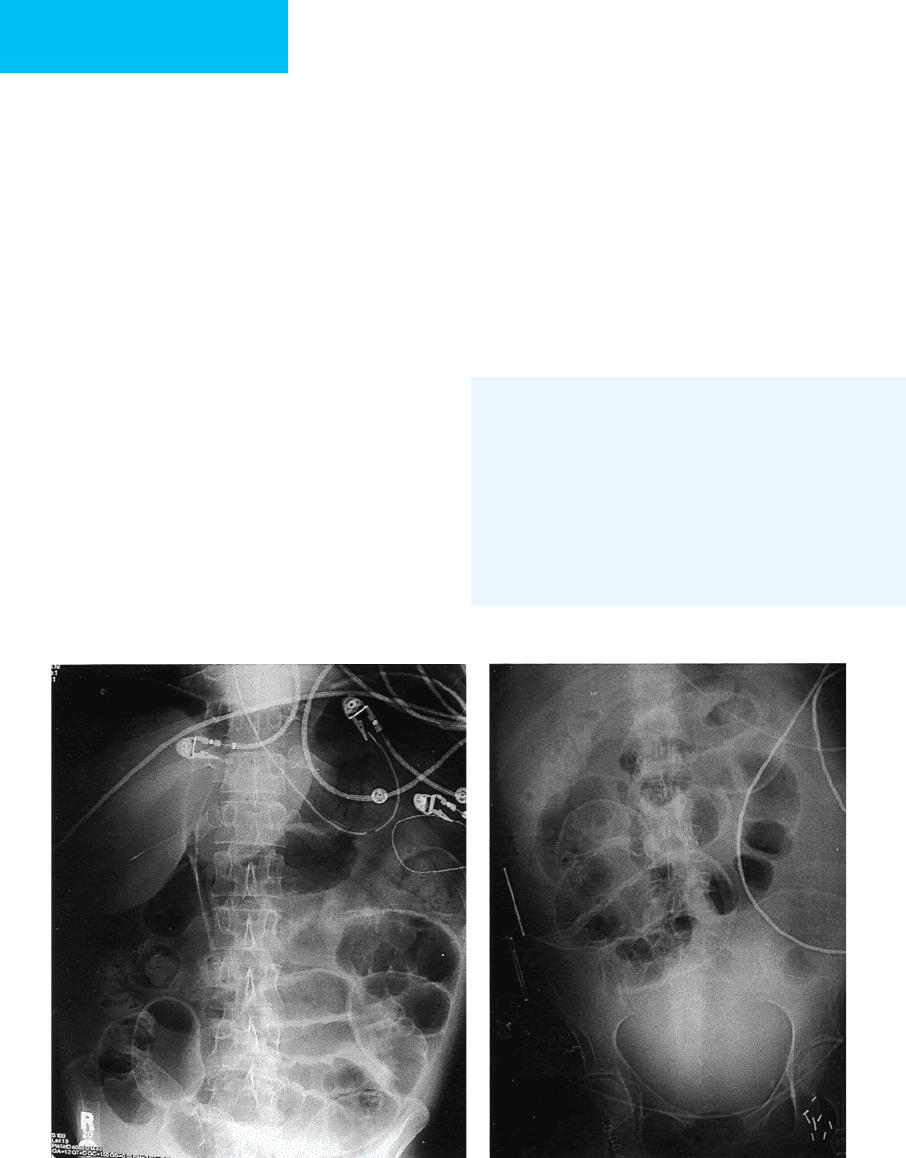

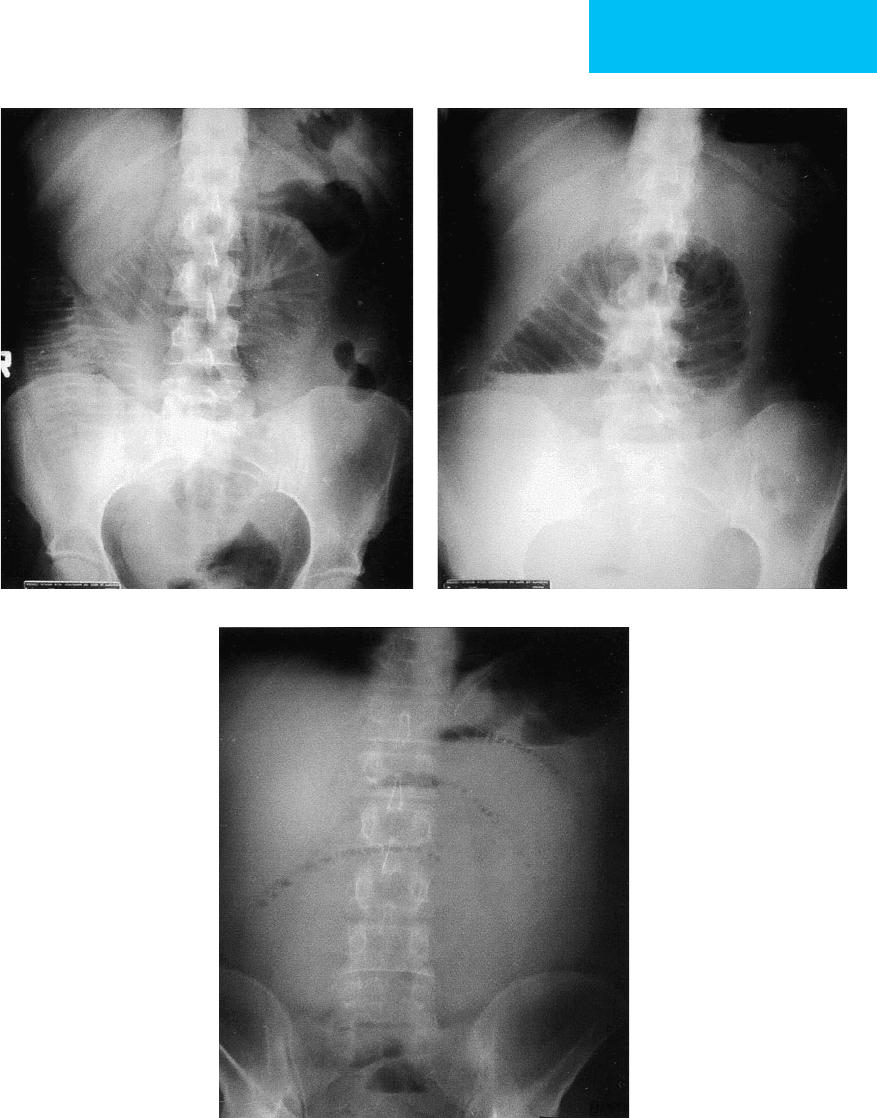

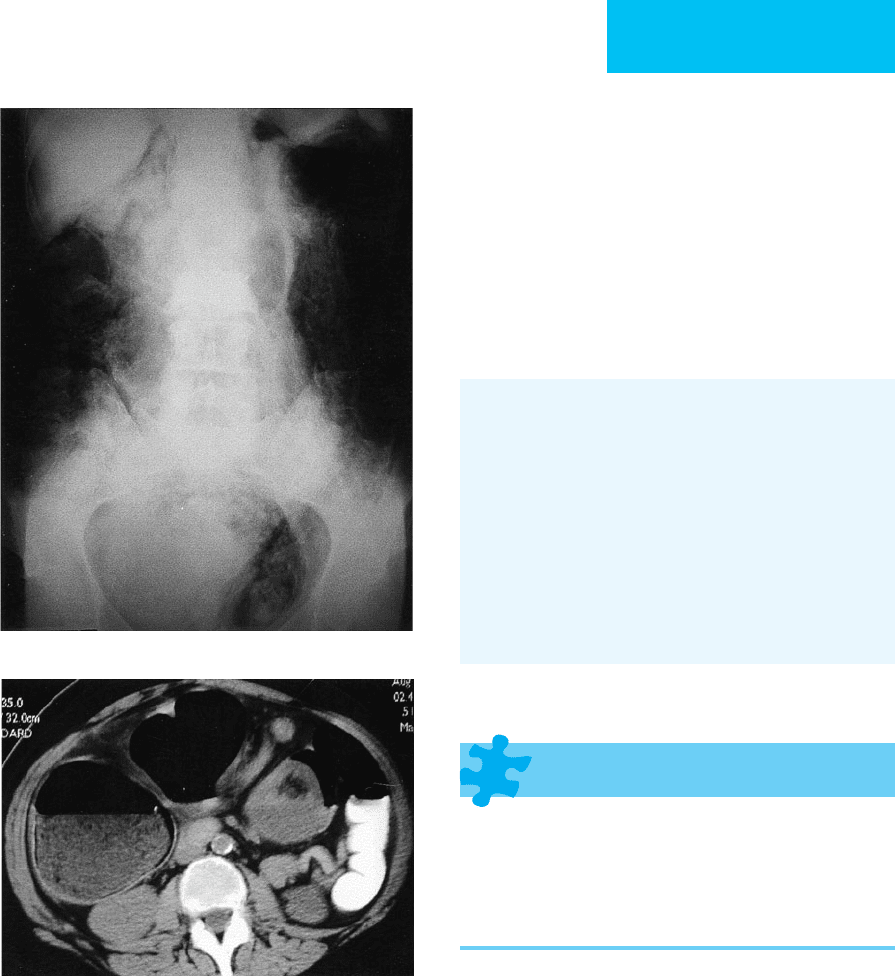

AB

Figure 7–22. A: Pneumoperitoneum in a 72-year-old man with perforated sigmoid diverticulitis. On a supine radi-

ograph, there is lucency over the right upper quadrant with visualization of falciform ligament. Both sides of small

bowel wall are visualized (Rigler’s sign) with characteristic triangles. B. Pneumoperitoneum in an 80-year-old man

after recent abdominal surgery. Supine radiograph demonstrates a more subtle example of Rigler’s sign.

IMAGING PROCEDURES

169

Bowel Obstruction

ESSENTIALS OF RADIOLOGIC

DIAGNOSIS

Asymmetric dilation of proximal bowel loops.

Normal or collapsed distal bowel loops.

Small bowel obstruction: Dilated U-shaped loops with

air-fluid levels (upright or decubitus films) or a single

loop with air-fluid levels at different heights.

Large bowel obstruction: Cecal distention, absence of

rectal gas, or “triple flexure” and “coffee bean” signs of

sigmoid volvulus.

CT scan: Excellent for detecting bowel obstruction and

confirming the cause.

General Considerations

Mechanical obstruction of the bowel is a relatively common

occurrence in hospitalized patients. In the general population,

bowel obstructions account for approximately 20% of acute

abdominal conditions. Obstruction usually results from extrin-

sic compression but can occur from luminal obstruction.

Without prompt attention, bowel obstruction may progress to

bowel infarction because of disruption of venous outflow and

subsequent arterial blood supply. Bowel infarction may progress

to mucosal ulceration, necrosis, and perforation. Mortality rates

for untreated obstruction have been as high as 60%.

Approximately three-fourths of bowel obstructions are

related to the small bowel (enteric) and one-fourth to the

colon. Small bowel obstructions are most commonly due to

adhesions from prior abdominal surgery. Adhesions can

form rapidly, sometimes within 4–10 days after surgery, or

may develop manifestations many years later. Other causes of

small bowel obstruction include hernias (external and internal),

primary and metastatic tumors, intussusception, inflamma-

tory bowel disease, abscesses, and trauma.

Large bowel obstructions are most often (60%) caused by

primary carcinomas of the distal (left) colon. Metastatic

tumor or invasion from cancers of surrounding organs,

diverticulitis, sigmoid volvulus, and fecal impaction also may

cause a distal colonic obstruction.

Radiographic Features

A. Plain Abdominal Radiographs—An abdominal series that

includes supine plus upright or decubitus views of the

abdomen is only 50–60% sensitive for small bowel obstruction.

Objective evidence of small bowel obstruction includes asym-

metric dilation (luminal diameter >3 cm) of small bowel prox-

imal to the site of obstruction, with normal or decompressed

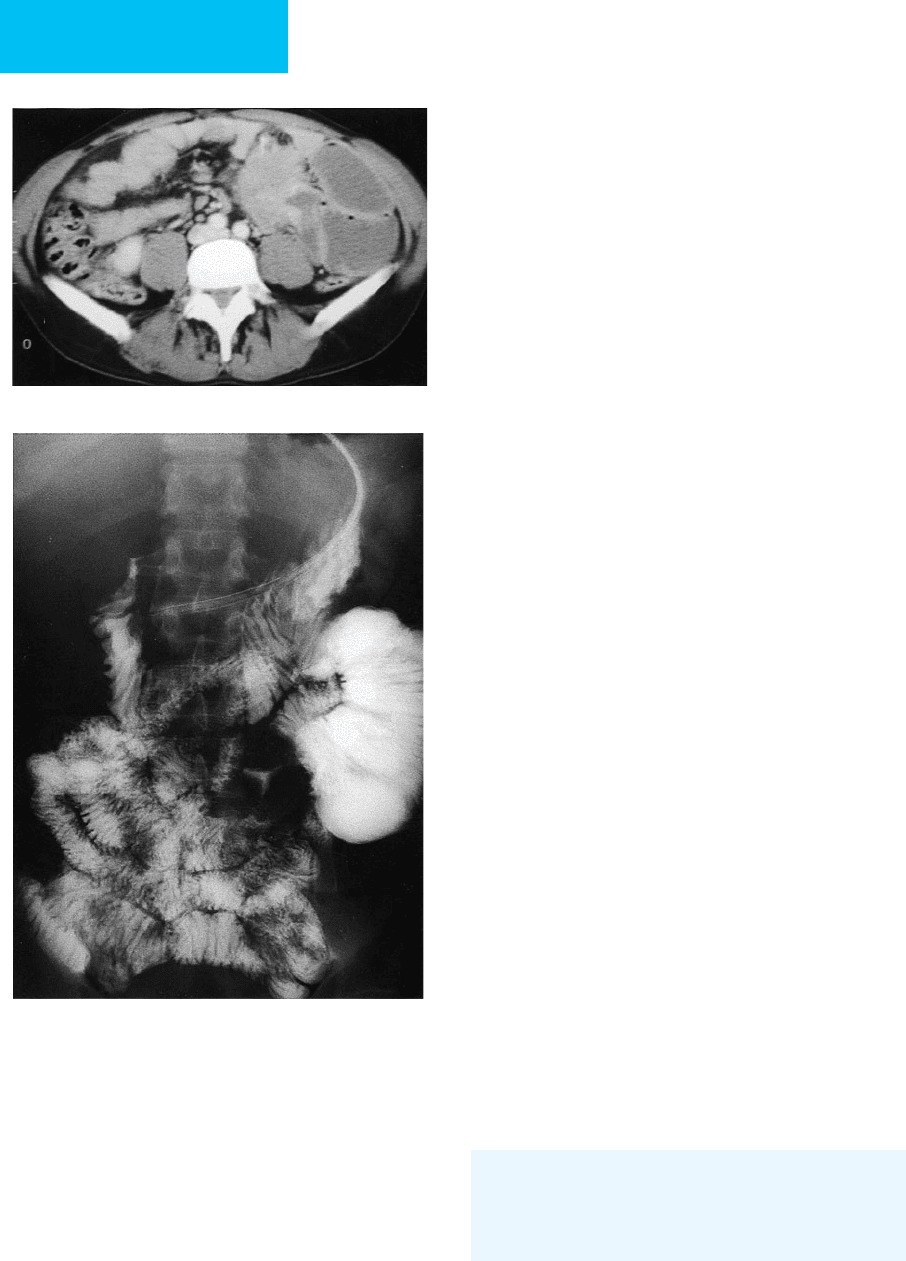

A

B

Figure 7–23. A. Pneumoperitoneum and pneu-

moretroperitoneum in a 76-year-old man after biliary

stent placement because of obstruction from pancre-

atic cancer. A supine radiograph shows characteristic

air under the diaphragm and surrounding liver. The

psoas muscles and kidneys are also outlined by gas,

confirming the presence of pneumoretroperitoneum.

B. Abdominal CT demonstrates ectopic gas and confirms

the diagnosis of pneumoperitoneum in the patient in

Figure 7–21.

CHAPTER 7

170

small bowel loops distally and normal to absent colonic gas.

However, these findings may not be seen in all patients who

present with a small bowel obstruction. More valuable is the

relative change in distention over time, and for this reason,

comparison of a series of studies is prudent. Other radi-

ographic signs include an inverted U-shaped loop of dilated

small bowel with air-fluid levels, multiple air-fluid levels, and

dynamic loops (air-fluid levels at varying heights in different

limbs of a loop). In some cases, a “string of pearls sign” can be

seen (Figure 7–24).

On a single supine film of the abdomen, dilated small

bowel loops may be mostly fluid-filled, with a minimal

amount of gas, or may be completely devoid of gas. In this

case, the film will be nonspecific, and additional views or CT

may be required. Diagnosis of small bowel obstruction may

be difficult because the presence of radiographic signs will

depend on the site, duration, and degree of obstruction.

Bowel distal to a complete obstruction takes 12–48 hours to

evacuate all its gas. Serial plain films sometimes are required

to capture these changes because films may be nonspecific if

imaging is performed too early.

Because of the limited utility of plain radiographs, helical

CT is now the preferred method for evaluating suspected

small bowel obstruction (Figure 7–25). In patients who can-

not undergo CT or if CT is unavailable, serial radiographs

may be taken after ingestion of enteric contrast material.

Although water-soluble contrast agents are preferred, espe-

cially for patients who are surgical candidates, they are

hypertonic and become progressively more dilute, limiting

the ability of the study to accurately identify the site of

obstruction. Barium is preferred in nonsurgical patients

because progressive dilution does not occur, and the site of

obstruction is more easily identified. However, in high-grade

obstructions, barium may thicken and become difficult to

evacuate. The high density of retained barium also degrades

CT images because of a beam-hardening artifact that results

in a nondiagnostic CT examination. Given these problems,

CT is the initial imaging procedure of choice if small bowel

obstruction is suspected.

In general, colonic obstruction (Figure 7–26) tends to occur

distally because most obstructing colon cancers occur in the dis-

tal large bowel. A single supine radiograph often fails to identify

the site of obstruction, and supplementary views—an upright

view, a right lateral decubitus view, or a prone view—may be

necessary to work up a possible obstruction and distinguish it

from an ileus. In large bowel obstruction, the cecum distends to

a greater degree than does the remainder of the colon regardless

of the site of obstruction. This follows from Laplace’s law, which

states that the pressure required to distend the walls of a hollow

structure is inversely proportional to its radius. The cecum has

the largest radius of any part of the large bowel. Generally, the

upper limits of normal for the transverse diameter of a large

bowel loop is 6 cm; for the cecum, it is 9 cm. However, these are

rough estimates only and may not hold true for a given patient.

Again, one must interpret, if possible, the relative change in dis-

tention with comparison studies over time. Perforation is a

dreaded complication of obstruction. The overall risk of cecal

perforation is low—approximately 1.5%—but may increase to

14% with delay in diagnosis. There is an increased risk of cecal

perforation if the luminal diameter exceeds 9 cm and persists

for more than 2–3 days.

B. Computed Tomography—Over the last 10 years, several

investigators have emphasized the value of CT scanning in

detecting bowel obstruction. Helical and multidetector CT

can produce multiplanar images to help determine whether

obstruction is present, the severity and level of obstruction,

the cause of obstruction, and whether strangulation or

ischemia is present. Current helical and multidetector tech-

nology permits evaluation of the abdomen and pelvis in 20

seconds to 2 minutes. Oral and intravenous contrast material

may not be required if experienced radiologists interpret the

scans. In most cases of small bowel obstruction, a transition

point between dilated and nondilated bowel can be demon-

strated. Identification of the transition zone and the cause of

obstruction, when not apparent on axial images, may be

aided by the multiplanar reformatting possible on current

CT scanners and image-processing workstations. Although

adhesions themselves are too thin to be imaged, most other

common causes of small bowel obstruction—including her-

nia, tumor, intussusception, postradiation fibrosis, and gall-

stone ileus—may be identified. The accuracy of CT is

90–95% in high-grade bowel obstruction but somewhat less

in low-grade obstruction.

Furukawa A et al: Helical CT in the diagnosis of small bowel

obstruction. Radiographics 2001;21:341–55. [PMID: 11259698]

Lappas JC, Reyes BL, Maglinte DD: Abdominal radiography

findings in small-bowel obstruction: Relevance to triage for

additional diagnostic imaging. AJR 2001;176:167–74.

[PMID:11133561]

Mak SY et al: Small bowel obstruction: Computed tomography

features and pitfalls. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol 2006;35:65–74.

[PMID: 16517290]

Nicolaou S et al: Imaging of acute small-bowel obstruction. AJR

2005;185:1036–44. [PMID: 16177429]

Thompson WM et al: Accuracy of abdominal radiography in acute

small-bowel obstruction: Does reviewer experience matter? AJR

2007;188:W233–8. [PMID: 17312028]

Ileus

ESSENTIALS OF RADIOLOGIC

DIAGNOSIS

Diffuse symmetric dilation of small and large bowel.

May be focal when adjacent to an inflammatory source.

Colonic ileus (Ogilvie’s syndrome) may be seen alone or

in conjunction with small bowel ileus.

IMAGING PROCEDURES

171

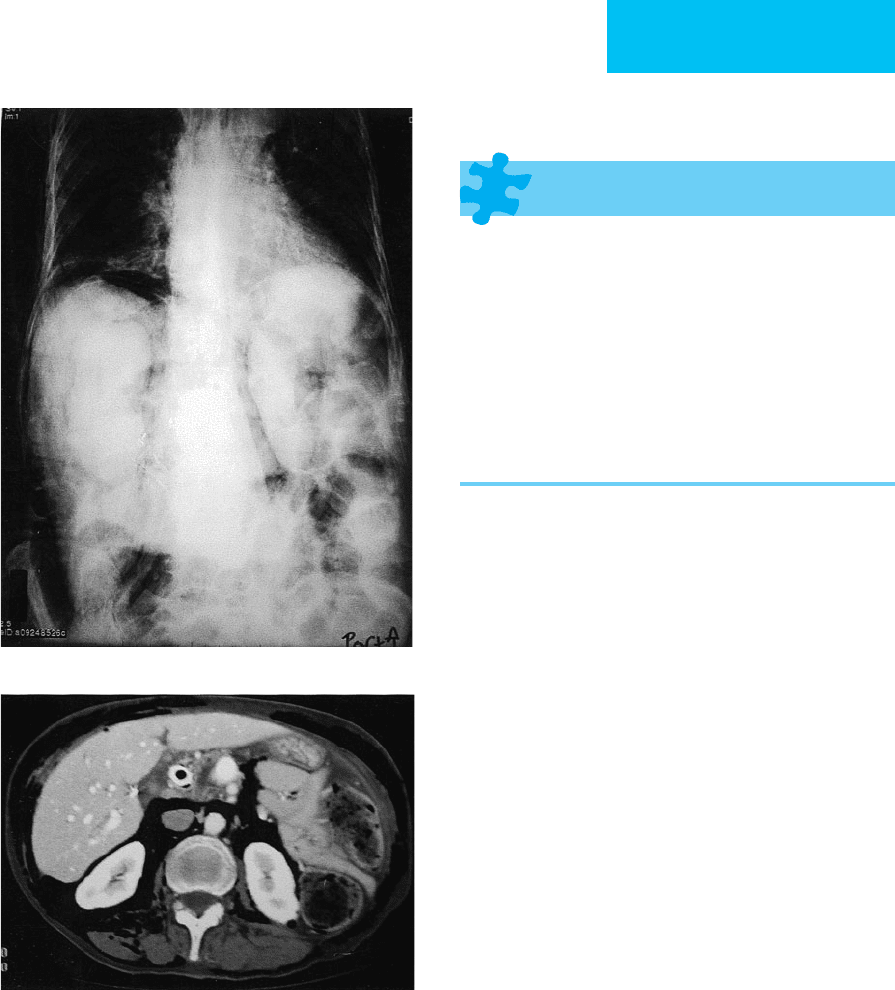

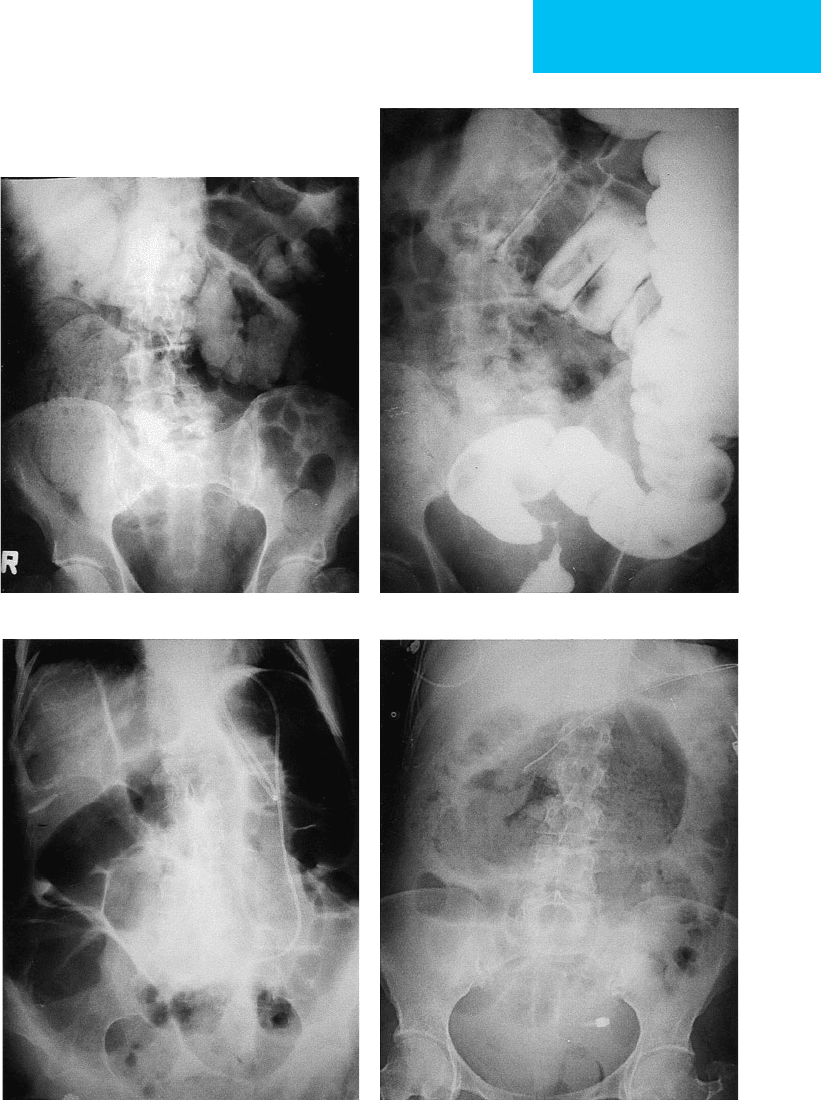

AB

C

Figure 7–24. A. Small bowel obstruction. Because of their widespread availability, conventional upright and supine

radiographs are a good first step in suspected small bowel obstruction, although sensitivity and specificity are low.

A supine radiograph demonstrates asymmetric dilation of the proximal small bowel (note plicae circulares) without

significant gas in the colon. B. In the same patient, an upright abdominal radiograph demonstrates a prominent

air-fluid level from proximal small bowel obstruction. C. The “string of pearls sign” in small bowel obstruction; an

upright radiograph demonstrates numerous air-fluid levels.

CHAPTER 7

General Considerations

Ileus is generalized dysfunction of bowel related to an

underlying disorder, usually most severe in the 2–4 days

following abdominal surgery with extensive bowel manip-

ulation. Dysfunction due to humoral, metabolic, and neu-

ral factors contributes to the overall process. Other

common causes include abdominal infections, peritonitis,

active inflammatory bowel disease, opioid or chemother-

apy use, electrolyte imbalances, visceral pain syndrome

(biliary or ureteral colic, ovarian torsion), and myocardial

infarction.

Radiographic Features

In the generalized form of ileus, the small and large

bowel are dilated but generally to a lesser degree than

seen in moderate to severe bowel obstruction (Figure 7–27).

In many cases, there is a significant overlap with clinical

and radiologic features of small bowel obstruction, and

differentiation on the basis of a single study may not be

possible. Serial radiographs, contrast studies with water-

soluble contrast agents or barium, or CT may be

required.

An intraabdominal inflammatory event (acute pancreatitis)

or trauma may produce a focal form of ileus. The dysfunc-

tional segment of bowel may lose peristaltic activity and

enlarge. This is known as a sentinel loop.

Colonic ileus—also known as intestinal pseudo-

obstruction or Ogilvie’s syndrome—usually presents in

elderly, debilitated, or bedridden patients with major

underlying systemic abnormalities, severe infection,

cardiac disease, or recent surgery. Progressive large

bowel distention is variably accompanied by small bowel

distention. Massive cecal distention compromises blood

flow and may be complicated by perforation, with a

mortality rate of 30–45%. As in the small bowel, colonic

ileus is not always diffuse and may be segmental, typi-

cally in the cecum. In cecal ileus, there is massive dila-

tion of the cecum. If the cecum is mobile, this condition

may be difficult to distinguish from cecal volvulus, and

a contrast examination may be necessary to make the

differentiation.

Conservative treatment, consisting of nasogastric tube,

rectal tube, or colonoscopic decompression, is successful in

78% of patients. Alternatively, surgical cecostomy may be

necessary. Percutaneous cecostomy may be offered to high-

risk patients.

Nunley JC, FitzHarris GP: Postoperative ileus. Curr Surg

2004;61:341–5. [PMID: 15276337]

Saunders MD, Kimmey MB: Colonic pseudo-obstruction: The

dilated colon in the ICU. Semin Gastrointest Dis 2003;14:20–7.

[PMID: 12610851]

∂

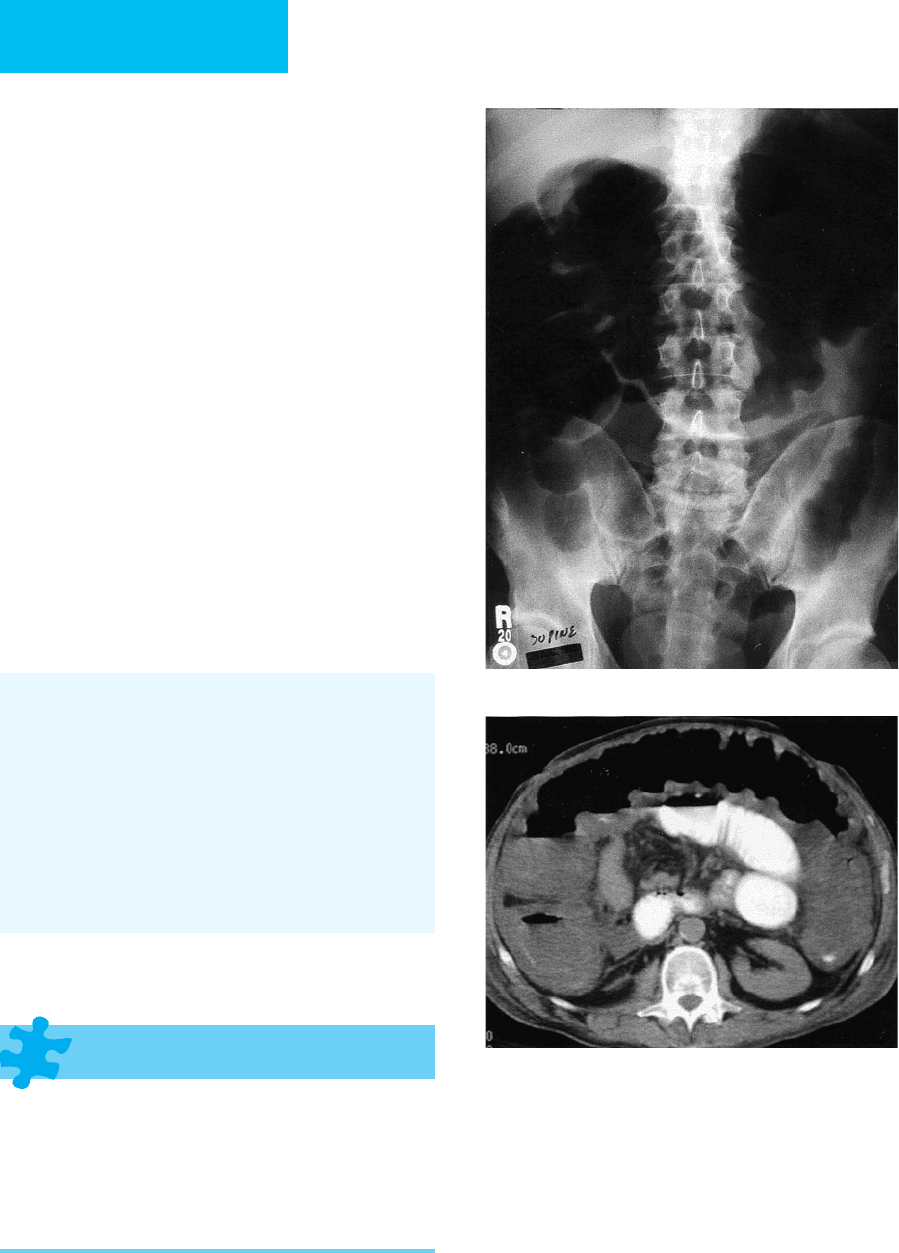

A

B

172

Figure 7–25. A. CT is excellent for diagnosing small

bowel obstruction and for detecting a cause (eg, mass,

intussusception, or hernia). In this patient, a large

leiomyosarcoma caused a high-grade small bowel

obstruction. B. In certain situations, following luminal

contrast material through the small bowel (small bowel

follow-through) may be helpful for detecting small

bowel obstruction. This study from the same patient

demonstrates an abrupt tapering of the bowel lumen

with dilated proximal bowel due to the mass.

IMAGING PROCEDURES

173

AB

CD

Figure 7–26. Large bowel obstruction. A. Most large bowel obstructions occur distally and are due to tumors or

diverticulitis. In this patient, the large bowel is diffusely dilated and filled with stool. B. A single-contrast barium

enema depicts a short segment annular carcinoma causing sigmoid colon obstruction. C. Sigmoid volvulus. On plain

radiograph, the dilated sigmoid colon may project over the right upper quadrant with a “coffee bean” appearance. The

remainder of the colon is dilated. D. Cecal volvulus. On plain radiographs, the dilated cecum is filled with stool and

projects over the midabdomen or sometimes the left upper quadrant. The small bowel is diffusely dilated.

CHAPTER 7

Intestinal Ischemia

ESSENTIALS OF RADIOLOGIC

DIAGNOSIS

Plain films: Early: normal or nonspecific dilation of

bowel; later: focal, edematous, thick-walled bowel

loops, gas in the superior mesenteric and portal veins,

pneumatosis intestinalis, ileus, and gasless abdomen.

Abdominal CT: bowel wall thickening, pneumatosis;

portal venous gas usually sign of infarction.

CT or MRA provides excellent evaluation of the larger

mesenteric arteries and veins.

Conventional angiography is infrequently needed but

may be confirmatory in some situations.

General Considerations

Early diagnosis of bowel ischemia and infarction remains diffi-

cult because of limited clinical and radiologic sensitivity.

Vascular insufficiency must be considered in elderly patients or

for any patient with atherosclerotic vascular disease, hypoten-

sion, cardiac failure, or arteritis. In young patients, vasculitis, a

hypercoagulable state, pregnancy, illicit use of cocaine, or

embolic sources (eg, patent foramen ovale) must be suspected.

Morbidity and mortality rates remain high (30–80%).

Ischemia has a variety of underlying causes, including

mesenteric arterial occlusion (ie, thrombus, embolus, or dis-

section), venous occlusion (ie, hypercoagulable states or

malignancy), nonocclusive mesenteric ischemia (ie,

vasospasm, myocardial infarction, or shock), and mechanical

obstruction, including colonic pseudo-obstruction. Any por-

tion of the small bowel may be affected; the cecum and dis-

tal left colon are the large bowel segments affected most

commonly. Rectal ischemia is infrequent because of the rec-

tum’s dual blood supply, but it may be seen in patients who

have had prior radiation therapy to that area.

Clinical symptoms are variable. Generally, abdominal

pain out of proportion to physical findings, and bloody

diarrhea may be suggestive of ischemic colitis. Segmental

ischemia often resolves spontaneously, but fibrotic strictures

may develop. Infarcted bowel must be surgically resected. In

selected patients, clots identified on IV contrast-enhanced

CT may be treated with angiographic interventional tech-

niques, including thrombolysis or stent placement.

Radiographic Features

A. Plain Radiographs—Edematous, thick-walled bowel,

pneumatosis intestinalis, and portal venous gas are the most

specific signs of ischemia and infarction but are insensitive.

More commonly, plain films are normal, show lack of

abdominal gas, or suggest focal ileus or small bowel obstruc-

tion (Figure 7–28).

B. Computed Tomography—Helical CT is important for

detecting early changes of ischemia. A high-quality helical CT

is usually performed with oral contrast material to opacify

and distend the small bowel along with rapid IV contrast

material injection (3 mL/s) to optimize opacification of the

superior mesenteric artery and vein. The CT features of

intestinal ischemia vary with its cause, chronicity, and sever-

ity. Bowel wall thickening is a sensitive but nonspecific early

finding and may be accompanied by a “target sign” appear-

ance of bowel caused by submucosal edema. Indirect signs of

ischemia include focal ascites, bowel distention, and mesen-

teric edema. In more advanced stages of bowel ischemia, the

presence of gas within the bowel wall or within the superior

mesenteric or portal vein makes the prognosis more grave.

Colonic ischemia generally results from hypoperfusion or

hypotension, and mesenteric thrombosis is rare. CT angiog-

raphy using newer-generation multidetector helical scanners

∂

174

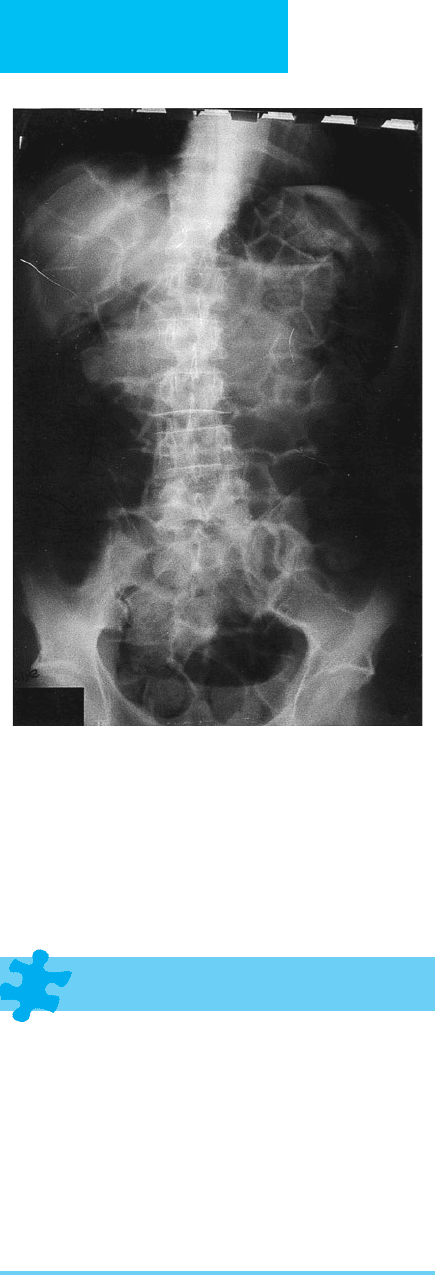

Figure 7–27. Ileus. Plain abdominal radiograph

demonstrates mild diffuse gaseous dilation of both the

small and the large bowel. No transition point is present.

IMAGING PROCEDURES

175

allows excellent vascular and intestinal wall assessment, aided

by three-dimensional image processing (eg, multiplanar,

volume-rendered, and maximum-intensity projection views).

Thrombus in the major mesenteric vessels may be detected.

However, a normal CT does not exclude ischemia, and if a

strong clinical suspicion is present—especially in patients

with vasculitis—angiography or surgery may be required.

C. Catheter Angiography—Angiography may be both diag-

nostic and therapeutic. Vasodilators may be used in conjunc-

tion with thrombolytic agents in certain patients. While

angiography remains the diagnostic standard in patients

with vasculitides given its unparalleled spatial resolution,

multidetector CT and modern MR scanners have narrowed

the resolution gap. Angiography has a limited role in colonic

ischemia because low-blood-flow states rather than occlu-

sion of the vasculature are most often the cause.

Bradbury MS et al: Mesenteric venous thrombosis: Diagnosis and

noninvasive imaging. Radiographics 2002;22:527–41. [PMID:

12006685]

Horton KM, Fishman EK: Multidetector CT angiography in the

diagnosis of mesenteric ischemia. Radiol Clin North Am

2007;45:275–88. [PMID: 17502217]

Kirkpatrick ID, Kroeker MA, Greenberg HM: Biphasic CT with mesen-

teric CT angiography in the evaluation of acute mesenteric ischemia:

Initial experience. Radiology 2003;229:91–8. [PMID: 12944600]

Nehme OS, Rogers AI: New developments in colonic ischemia.

Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2001;3:416–9. [PMID: 11560800]

Shih MC, Hagspiel KD: CTA and MRA in mesenteric ischemia: 1.

Role in diagnosis and differential diagnosis. AJR 2007;

188:452–61. [PMID: 17242255]

Colitis

ESSENTIALS OF RADIOLOGIC

DIAGNOSIS

Colonic wall thickening and nodularity associated with

paralytic ileus.

Infiltration of pericolonic fat, often seen on CT.

Plaque-like filling defects are suggestive of pseudomem-

branous colitis.

General Considerations

Inflammatory bowel disease, ischemia, and infections are the

most common causes of colitis. Patients present with pain,

bloody diarrhea, cramping, fever, and leukocytosis.

Infectious colitis may be bacterial, viral, fungal, or parasitic.

Stool cultures, serologic tests, or colonic biopsy may be

required.

Pseudomembranous colitis—the most common cause of

colitis in hospitalized populations—is a complication of

antibiotic therapy. Clostridium difficile produces an entero-

toxin that causes mucosal ulceration and edema and the

development of pseudomembranes. The process may be

focal or diffuse.

Figure 7–28. Colonic ischemia. A. Plain radiograph

demonstrates mottled lucency of the wall of the ascend-

ing colon consistent with pneumatosis. B. Abdominal CT

is excellent for confirmation of pneumatosis.

A

B

CHAPTER 7

176

Neutropenic colitis is typically seen in patients undergo-

ing chemotherapy or bone marrow transplantation with

myelosuppression. Although involvement can be diffuse, it

typically affects the ascending colon, cecum, appendix, and

terminal ileum. If cecal inflammation is present, then the

term typhlitis (or necrotizing enterocolitis) is used.

Radiographic Features

Although usually normal or nonspecific, plain radiographs

may reveal colonic fold thickening and nodularity. Features

of paralytic ileus may be present. Contrast studies such as a

barium enema should be avoided but can be performed care-

fully with water-soluble agents only if absolutely necessary

(Figure 7–29). Although abdominal CT is an excellent test, it

may be normal in early infectious colitis. In more advanced

cases of infectious colitis and in pseudomembranous colitis,

mural thickening is more severe, averaging 15–20 mm, with

a target or halo pattern. An accordion-like pattern reflecting

haustral thickening may be produced in addition to peri-

colonic inflammatory changes and lymphadenopathy. In

neutropenic colitis (typhlitis), similar features are present,

but most commonly in the right colon. Occasionally in

advanced cases, pneumatosis intestinalis and frank perfora-

tion may develop.

Horton KM, Corl FM, Fishman EK: CT evaluation of the colon:

Inflammatory disease. Radiographics 2000;20:399–418. [PMID:

10715339]

Kawamoto S et al: Pseudomembranous colitis: Spectrum of imag-

ing findings with clinical and pathologic correlation.

Radiographics 1999;19:887–97. [PMID: 10464797]

Ramachandran I et al: Pseudomembranous colitis revisited:

Spectrum of imaging findings. Clin Radiol 2006;61:535–44.

[PMID: 16784938]

Thoeni RF, Cello JP: CT imaging of colitis. Radiology

2006;240:623–38. [PMID: 16926320]

Zalis M, Singh AK: Imaging of inflammatory bowel disease: CT

and MR. Dig Dis 2004;22:56–62. [PMID: 15292695]

Toxic Megacolon

ESSENTIALS OF RADIOLOGIC

DIAGNOSIS

Gaseous colonic distention, which may be diffuse or

segmental.

Effacement of haustra, edematous folds (thumbprinting),

relative paucity of feces.

Common complication of a number of inflammatory

conditions, notably ulcerative colitis.

Figure 7–29. A. Colitis. Plain radiograph demon-

strates mild dilation and severe fold thickening

(thumbprinting) of transverse colon in this case of

pseudomembranous colitis. B. Abdominal CT also

demonstrates mural colonic thickening with associated

infiltration of the pericolonic fat.

A

B