Bogucki P., Crabtree P. Ancient Europe 8000 B.C.-A.D. 1000: Encyclopedia of the Barbarian World. Volume 2

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Pre-Viking and Viking Age Denmark (vol. 2, part

7).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ambrosiani, Björn, and Helen Clarke, eds. Early Investiga-

tions and Future Plans: Investigations in the Black

Earth. Birka Studies 1. Stockholm, Sweden: Riksantik-

varieämbetet and Statens Historiska Muséet, 1992.

Baudou, Evert, et al. Archaeological and Palaeoecological

Studies in Medelpad, North Sweden. Kungliga Vitterhets

Historie och Antikvitets Akademien. Stockholm, Swe-

den: Almqvist and Wiksell, 1978.

Calissendorff, Karin, et al. Iron and Man in Prehistoric Swe-

den. Translated and edited by Helen Clarke. Stock-

holm, Sweden: Jernkontoret, 1979.

Callmer, Johan. “Recent Work at A

˚

hus: Problems and Ob-

servations.” Offa 41 (1984): 63–75.

———. “Production Site and Market Area.” Meddelanden

fra˚n Lunds Universitets Historiska Museum 1981–1982

7 (1983): 135–165.

Clarke, Helen, and Björn Ambrosiani. Towns in the Viking

Age. New York: St. Martin’s, 1991.

Dahlström, Carina. “The Viking Age Harbour and Trading

Place at Fröjel, Gotland: A Summary of the Excavation

during the Summer of 2001.” Viking Heritage 4

(2001): 20–22.

Edgren, Bengt, Gustaf Trotzig, and Erik Wegraeus. Eketorp:

The Fortified Village on Öland. Stockholm, Sweden:

Central Board of National Antiquities, 1985.

Hagberg, Ulf Erik. The Archaeology of Skedemosse. 4 vols.

Stockholm, Sweden: Almqvist and Wiksell Internation-

al, 1967–1977.

Hodges, Richard. Dark Age Economics: The Origins of Towns

and Trade,

A.D. 600–1000. 2d ed. London: Duckworth,

1989.

Holmqvist, Wilhelm, et al., eds. Excavations at Helgö. Vols.

1–14. Stockholm, Sweden: Kungliga Vitterhets Histo-

rie och Antikvitets Akademien, 1961–2001.

Jansson, Sven B. F. Runes in Sweden. Translated by Peter

Foote. Stockholm, Sweden: Gidlunds, 1987.

Jesch, Judith. Women in the Viking Age. Woodbridge, Suf-

folk, U.K.: Boydell Press, 1991.

Larsson, Lars. “Uppa˚kra: A Centre in South Sweden in the

1st Millennium

A.D.” Antiquity 74 (2000): 645–648.

Nylén, Erik, and Jan Peder Lamm. Stones, Ships, and Symbols:

The Picture Stones of Gotland from the Viking Age and

Before. Stockholm, Sweden: Gidlunds, 1988.

Ohlsson, T. “The Löddeköpinge Investigation II: The

Northern Part of the Village Area.” Meddelanden fra˚n

Lunds Universitets Historiska Museum 1979–1980 5

(1980): 68–111.

———. “The Löddeköpinge Investigation I: The Settle-

ment at Vikshögsvägen.” Meddelanden fra˚n Lunds Un-

iversitets Historiska Museum 1975–1976 1 (1976): 59–

161.

Ramqvist, Per H. Gene: On the Origin, Function, and Devel-

opment of Sedentary Iron Age Settlement in Northern

Sweden. Umea˚, Sweden: University of Umea˚ Depart-

ment of Archaeology, 1983.

Roesdahl, Else. The Vikings. Translated by Susan M. Marge-

son and Kirsten Williams. New York: Penguin, 1992.

Roesdahl, Else, and David M. Wilson, eds. From Viking to

Crusader: Scandinavia and Europe, 800–1200. New

York: Rizzoli, 1992.

Sawyer, Birgit. The Viking-Age Rune-Stones: Custom and

Commemoration in Early Medieval Scandinavia. Ox-

ford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

Sawyer, Peter, ed. The Oxford Illustrated History of the Vi-

kings. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997.

Stjernquist, Berta. “Uppa˚kra: A Central Place in Ska˚ne dur-

ing the Iron Age.” Lund Archaeological Review 1995

(1996): 89–120.

Widgren, Mats. Settlement and Farming Systems in the Early

Iron Age: A Study of Fossil Agrarian Landscapes in

Östergötland, Sweden. Stockholm, Sweden: Almquist

and Wiksell, 1983.

Zachrisson, Inger. “A Review of Archaeological Research on

Saami Prehistory in Sweden.” Current Swedish Archae-

ology 1 (1993): 171–182.

N

ANCY L. WICKER

PRE-VIKING AND VIKING AGE SWEDEN

ANCIENT EUROPE

541

EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

PRE-VIKING AND VIKING AGE DENMARK

■

Although Danish Vikings are famous in history,

much of the Viking Age lacks indigenous docu-

ments; thus, “history” largely reflects the views of

Denmark’s neighbors, leading to the popular con-

notation of a warrior culture bent on senseless or

greedy destruction. In fact, in many ways Denmark

was unremarkable during this era: all of the incipient

post-Roman European states were equally engaged

in mutual raiding, warfare, and conquest. Given the

uneven historic record—literate European chroni-

clers versus largely prehistoric Danes, archaeology,

along with careful reading of what documents there

are, is the best way to understand circumstances sur-

rounding the formation of Denmark.

Before the Viking era,

A.D. 800–1050, econom-

ic and sociopolitical development in Germanic Eu-

rope, including Denmark, was profoundly influ-

enced by interaction with the Roman Empire,

whose borders lay along the Rhine; thus, the period

from

A.D. 1–400 is called the Roman Iron Age.

Many traditions important in the state-building Vi-

king Age are rooted here: the indigenous concept

of the Danish provinces as loosely allied chiefly peer

polities; the thing, a regularly scheduled civic meet-

ing; a social code balancing “ordinary” people with

the military hierarchy; and a tradition of long-

distance trade. After Rome’s fall, a period of post-

Roman economic and political reorganization is re-

ferred to as the Germanic Iron Age,

A.D. 400–800.

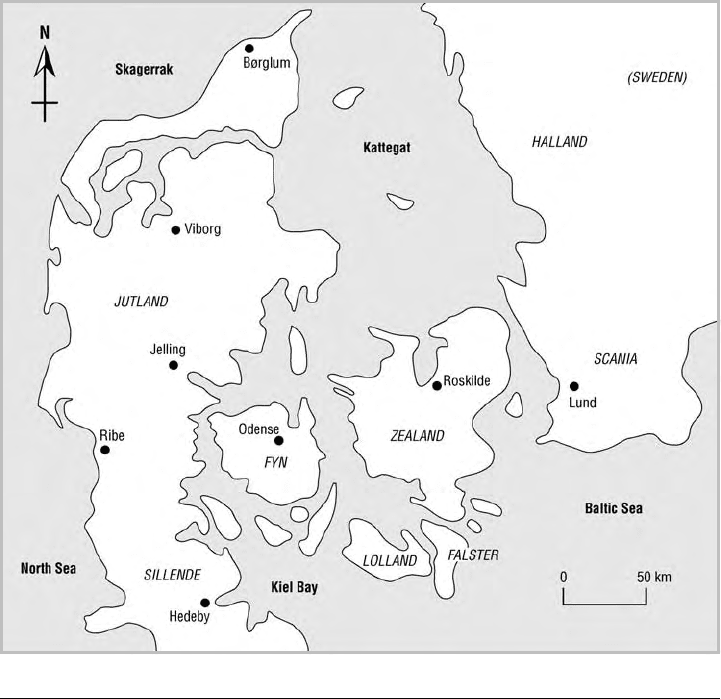

Denmark is a small, mostly archipelagic land

mass, consisting of the Jutland peninsula, four large

islands—Zealand, Fyn, Lolland, and Falster—and

470-odd small islands. Before 1654 Denmark in-

cluded Scania and Halland, now Sweden. This ge-

ography in part determined the location of Roman

Iron Age chiefdoms.

DENMARK IN THE ROMAN AND

GERMANIC IRON AGES

Roman documents shed some faint light on the re-

gion, but like all nonindigenous texts, reflect out-

side views. Roman-Germanic interaction led to the

writing of Germania by the Roman politician-

historian Tacitus, around

A.D. 98, and his descrip-

tion is considered fairly reliable. Tacitus describes a

social code wherein leaders did not have unlimited

power and required the assent of an assembly in

making decisions. Several small chiefdoms operat-

ing on these principles coexisted simultaneously in

the Roman era, in continual competition, yet inter-

acting via the exchange of Roman goods. In times

of warfare with Rome or other “outsiders,” a single

warlord was selected to lead them collectively for

short periods, but the support of his peers was re-

quired. If an overly ambitious leader seized too

much power, the social code actively encouraged his

assassination. Other typical chiefly leveling mecha-

nisms, such as extravagant feasting and the distribu-

tion of treasure to followers, kept a balance of

power, a tradition that continued in later times.

Tacitus is amply validated through archaeologi-

cal data. Competing polities and their chiefly cen-

ters can be identified by clusters of Roman imports,

elite or warrior burials with Roman goods, and sac-

rificial deposits that were made into water—often

the arms and armor of local foes, including Roman-

542

ANCIENT EUROPE

Selected pre-Viking and Viking Age sites in Denmark.

made swords. Some competing centers were located

on the large, defensible, fertile islands. Similarly,

bountiful Scania and Halland supported local rulers.

Jutland was agriculturally poorer but ideal for cattle,

and chiefly polities also rose there.

Chiefdoms were based upon what is commonly

called a prestige-goods economy. Prestige goods

are nonutilitarian objects that are indispensable for

social and political relations—in this case, Roman

imports of weapons, ornaments, and feasting and

drinking equipment. In return, the Romans re-

ceived leather, fur, meat, cloth, and probably slaves.

In Denmark, personal reputation and power were

intertwined with the ability and degree to which

one could control and own Roman goods, a system

that only worked if their flow was controlled by an

elite minority. In return for sharing prestige goods

with lower-level elites for their own legitimation,

chiefs received staple tribute: livestock, grain, and

other supplies. Lower-level elite in turn extracted

tribute from farmers in return for their services in

defense, upholding law, and overseeing ritual activi-

ties. Grave goods reflect this hierarchy: a few have

the full complement of prestige items, others less

but still rich, while many have small quantities of

less valuable Roman items. War chiefs had much

power within society but were balanced by the

thing, a regular meeting of freemen—and possibly

some women, if we infer from some later sources—

who could vote against the plans of chiefs. In addi-

tion, a chief’s son was not automatically a chief; all

contenders had to prove themselves, leading to a

degree of upward mobility in society. One of the

greatest changes during the Viking Age was the re-

placement of this system with a more powerful, cen-

tralized leadership and the ascribed inheritance of

rulership.

In the Roman era, “Denmark” consisted of

many peoples. A long-debated question has thus

been “when did the Danes become the Danes?” By

combining archaeology and documents, we find

that the answer lies in understanding the social and

PRE-VIKING AND VIKING AGE DENMARK

ANCIENT EUROPE

543

political changes between the Roman, Germanic,

and Viking Ages. When Rome fell in the mid-fifth

century, so did the prestige economy, but most of

Denmark’s small realms did not collapse: they reor-

ganized and expanded. A few groups found them-

selves in disarray and sought new lands, leading to

what is called the Migration period, when Lango-

bards, Teutons, and others overran the Continent

and staked a claim. Despite this, around

A.D. 550,

Gothic writings indicate that many small polities in

Denmark were being consolidated into bigger polit-

ical units during the Germanic Iron Age.

DENMARK IN THE VIKING AGE

While historians mark the beginning of the Viking

Age in the 790s by the first Danish sea raids on En-

gland, archaeologists are less interested in events

than in processes, and they track a gradual but sig-

nificant transition in political and economic organi-

zation between the eighth and ninth centuries, and

beyond.

In the 700s, Frankish and English records of

political, military, and economic interactions with

the north describe the Danes as one people ruled by

a king, and Denmark as comprising Jutland, all the

islands, and Scania. Conversely, other texts state

that there were simultaneously two or even three

Danish kings, and to further complicate the picture,

later indigenous chronicles state that there were

sometimes one, two, or five kings.

These conflicting representations reflect the fact

that protracted conflicts with the Franks elevated

the temporary overlord to a more permanent ruler,

or king, while the ability to claim this new position

still rested on the old traditions of successful war-

fare, personal reputation, and distribution of wealth

to followers. Several early Danish rulers were assassi-

nated by their own people, also after ancient cus-

tom. During the 800s, a rapid succession of leaders

claimed the Danish crown, fought among each

other, and were overthrown, all calling themselves

kings in the process. During the ninth and tenth

centuries, some failed claimants grabbed parts of

Europe as small kingdoms, also perhaps calling

themselves Danish kings. Later, when the Danes

ruled England and Denmark, a father might make

his son a “sub-king” in Denmark. Slowly, Danish

kings became more permanent and powerful. Sons

began to inherit, some as adolescents or children, a

clear sign of a shift from achieved to ascribed status.

To legitimize themselves in a world with new rules,

new forms of marking and holding power emerged.

One of the most prominent is at Jelling in central

Jutland.

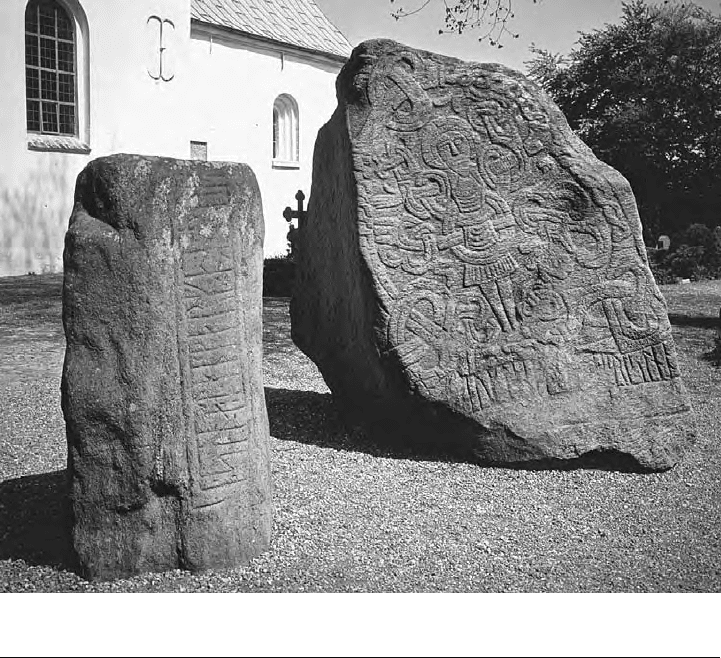

Jelling has no habitation: it is a symbolic center

consisting of royal monuments and runic inscrip-

tions (fig. 1). Some archaeologists see it as a “na-

tionalist” response to ever-threatening Franco-

Germans, others as a king’s attempt to firmly legiti-

mize his rule with both monumental architecture

and written texts proclaiming his own power. These

intertwined purposes are probably both true.

At Jelling, around

A.D. 950, King Gorm raised

a rune stone to his wife, Thyra, calling her the

adornment of Denmark—the first written reference

to the kingdom. Olaf Tryggvason’s Saga mentions

that Gorm (who reigned from about 920 to 950)

cleared all remaining “petty kings” from Denmark,

conquered the Slavs, and persecuted proselytizing

Christians. A second rune stone was raised by

Gorm’s son King Harald Bla˚tand, commemorating

his parents, his rule of a unified kingdom (from

about

A.D. 950 to 980), and its Christianization.

Jelling also sports two monumental earthworks:

a cenotaph 77 meters across and 11 meters high,

and a burial mound 65 meters across and 8.5 meters

high, the largest in Denmark. When excavated, no

remains, only rich grave furnishings, were found,

male and female. When Harald eventually became

Christian at about

A.D. 970, the mound was careful-

ly opened and his parents’ bones were apparently re-

moved to the Jelling church. Traces of this wooden

stave church were excavated in the 1980s, yielding

the disarticulated bones of an elderly man, clearly in

secondary context, perhaps those of Gorm.

Unification of the state can be seen archaeologi-

cally. At the transition between the reigns of Harald

and his son, Svein Forkbeard, a system of fortified

military and administrative centers was established

all over the kingdom, dated dendrochronologically

to

A.D. 980. These so-called Trelleborg fortresses

indicate the extent of royal authority at the turn of

the first millennium (fig. 2). Likewise, rune stones

in a centralized style called “after-Jelling” cover the

same geographic range. Also established were so-

called magnate sites, estates of high-level elites who

oversaw the king’s business. Central structures,

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

544

ANCIENT EUROPE

Fig. 1. Viking Age stones with runic inscriptions from Jelling, Denmark. COURTESY OF THE NATIONAL

MUSEUM OF DENMARK. REPRODUCED BY PERMISSION.

25–40 meters long with slightly curved walls, are

called “Trelleborg” houses, since they are nearly

identical to the large elite houses found at the Trel-

leborg administrative sites; so similar, in fact, that

some suggest they were designed and built by a

royal master-builder. Several have been excavated;

in addition to large houses, there is evidence of at-

tached crafts specialists, especially in metallurgy,

and extensive barns and stables for many cattle and

horses.

ECONOMY AND TRADE IN THE

VIKING AGE

Although the Viking Age is traditionally associated

with the sack of towns and monasteries in continen-

tal Europe and England, archaeologists studying

Viking activities in global perspective conclude that

they came not from innate hostility toward Chris-

tians or outsiders but rather were part of a much

larger economic cycle. It is useful to divide Viking

contacts with the rest of the world into phases. In

early Viking Age expeditions, local chiefs sought

wealth during a period of political change: at home,

new, centralized rulers were gaining power, so local

leaders sought new means of legitimation, wealth,

and fame. Over the course of the eighth to tenth

centuries, raiding and trading were predicated

mostly upon the economic booms and busts of the

Arabian caliphates and the Byzantines, seen in the

composition of coin hoards from different eras.

During boom periods, chiefs gained wealth by trad-

ing to the east. When these sources failed, they

gained wealth by both trading and raiding to the

west. Kings, charged with ruling at home and de-

fending the borders against the Franks—who were

actively trying to conquer Denmark in the first quar-

ter of the ninth century—had little or nothing to do

with these opportunistic raids.

In the Middle Viking Age, exiled or defeated

royal pretenders sought new territories to overtake

and rule, eventually settling in Scandinavian en-

claves in Normandy, Ireland, York, the Faeroes, and

other northern islands, bringing both conflict and

trade with them. Finally, in the Late Viking Age, le-

gitimate Danish kings conquered whole nations,

PRE-VIKING AND VIKING AGE DENMARK

ANCIENT EUROPE

545

Fig. 2. The fortress of Fyrkat in Denmark. COURTESY OF THE NATIONAL MUSEUM OF DENMARK.

REPRODUCED BY PERMISSION.

bringing them under Denmark’s imperial sway.

While collectively lumped together and called the

Viking Age by historians, these phases represent

very different strategies and circumstances motivat-

ing Viking activity.

The domestic economy consisted of mixed agri-

culture in the fertile islands, Scania and Halland,

whereas husbandry predominated on Jutland.

These products were important to the state, but one

of the most important props for newly emerging

rulers was their ability to control or administer

trade. Even after Rome’s fall, rulers maintained

short-distance trade in luxuries to reinforce their

rank in local society, and Jutland lay on sea-trade

routes. Beginning around

A.D. 700, proto-urban

centers called “emporia,” with permanent crafts-

people and traders, arose to serve as both import

and production sites. Precious metals and gems, ta-

bleware and glass, wine, textiles, and weapons came

from all over western Europe, while local people

worked iron, bone, glass, bronze, clay, and many

other materials that are found archaeologically. Ex-

tensive workshop quarters have been excavated at

sites such as Ribe and Hedeby. Cattle trade is seen

in strata consisting primarily of dung from beasts

penned for market. In these commercial centers,

elites built fortifications, churches for Christian

traders, and collected taxes and tolls; in return, mer-

chants could expect protection from thieves, repair

and maintenance of harbors and wharves, officials to

witness agreements and transactions, and enforce-

ment of the laws of fair trade. The taxes and reve-

nues Danish rulers collected are explicitly referred

to in Frankish texts: a series of massive earthworks,

collectively called the Danevirke, were constructed

by Danish rulers as a defense against the Franks over

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

546

ANCIENT EUROPE

the course of the eighth and ninth centuries, but

these walls also aided taxation on trade by control-

ling movement across the border.

Between the mid- and late tenth century, many

new towns were founded: Viborg, the national

thing where kings were still “elected” by the people;

A

˚

lborg, guarding the inland waterways of the Lim-

fjord; Lund, the Dane’s bishopric in Scania with its

cathedral; Odense; Roskilde; and others. Just after

the millennium, kings extended their power to col-

lect taxes and conscript more military service, and

they conferred more power on the growing church.

Knut the Great ruled a large empire including En-

gland, Denmark, and parts of Norway. All was not

quiet at home: several provinces rebelled, hoping to

regain autonomy, but the state, forged from the

conflicts and resolutions of the Viking Age, had be-

come too powerful to resist. Knut’s empire saw the

largest extent of Viking Age Denmark; his sons lost

their grip on this realm, and by 1042, the last Viking

king, whose reign spanned the transition to the

Early Middle Ages, was Sven Estridsen, who ruled

a Christianized, centralized, and mostly unified

Denmark. Sven made a final and unsuccessful at-

tempt to reconquer England in 1069–1070, but

with his passing in 1074, the Viking Age was truly

at an end.

See also Emporia (vol. 2, part 7); Pre-Viking and Viking

Age Norway (vol. 2, part 7); Pre-Viking and Viking

Age Sweden (vol. 2, part 7).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hedeager, Lotte. Iron Age Societies: From Tribe to State in

Northern Europe, 500

B.C. to A.D. 700. Oxford: Black-

well, 1992.

Jones, Gwyn. A History of the Vikings. 2d ed. London and

New York: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Randsborg, Klavs. The First Millennium A.D. in Europe and

the Mediterranean. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge Uni-

versity Press, 1991.

———. The Viking Age in Denmark: The Formation of a

State. London: Duckworth, 1980.

Roesdahl, Else. Viking Age Denmark. Translated by Susan

Margeson and Kirsten Williams. London: British Muse-

um Publications, 1982.

Sawyer, Birgit, and Peter Sawyer. Medieval Scandinavia:

From Conversion to Reformation circa 800–1500. Min-

neapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1993.

Thurston, Tina L. Landscapes of Power, Landscapes of Con-

flict: State Formation in the South Scandinavian Iron

Age. Fundamental Issues in Archaeology. New York:

Kluwer/Plenum, 2001.

T

INA L. THURSTON

PRE-VIKING AND VIKING AGE DENMARK

ANCIENT EUROPE

547

EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

FINLAND

■

The Late Iron Age can be said to have begun in Fin-

land around

A.D. 400. This last prehistoric period

continued as long as eight centuries in parts of east-

ern Finland. During this time, population expand-

ed, settlements spread, and trade contacts broad-

ened.

WAY OF LIFE

Most Finns continued to live as semisedentary farm-

ers practicing the slash-and-burn technique of field

use. This method of agriculture requires that an area

of natural growth be burned and the ash used as a

supporting nutrient for several seasons of crop

growth. When the land no longer produces ade-

quately, it is allowed to lie fallow until it fully regen-

erates. Traditional Finnish households might move

every generation or so in search of fresh arable land.

Slash-and-burn cultivation, which did not re-

quire much digging, was an excellent adaptation to

most of Finland’s southern and central landscape.

Large areas of forests were often so stony that per-

manent clearance and the use of a heavy plow to cut

fields of straight furrows was all but impossible.

Slash-and-burn cultivation, however, cannot be

practiced intensively in just one area, so most of the

Finnish population remained dispersed throughout

vast wilderness tracts. This dispersal of settlement

occurred not only for cultivation reasons but also to

gain access to good forest pasturage, hunting lands,

and fishing sources. Finnish men might travel great

distances during certain times of the year to hunt or

fish in wilderness territories. Historical sources sug-

gest that specific areas may have been claimed for

use by certain kin- or clan-based groups.

TRADE CONTACTS AND

CULTURAL INFLUENCES

The increased raiding and trading activity of the Vi-

king Age began in Scandinavia. Finland, too, was

growing restless and making new contacts abroad.

Swedish farmers immigrated in earnest beginning

around

A.D. 400 to the A

˚

land Islands off the coast

of Varsinais Suomi, greatly changing the character

of the population. More than three hundred Late

Iron Age sites are known in the archipelago.

As the first millennium

A.D. drew to a close, the

focal points of Finnish wealth and influence, based

on long-distance trade, migrated eastward to Häme

and Karelia. Before the medieval period of Swedish

political domination throughout the country, Fin-

land had no centralized towns or government such

as were typical elsewhere in Europe. Nevertheless,

Finns were still able to organize themselves and rec-

ognize leadership on a regional basis in order to

maintain systems of defensive hillforts, the distribu-

tion of rights to various northern hunting and fish-

ing grounds, and the protection and operation of

long-distance trade routes spanning the breadth of

the country and beyond. The details of this kind of

organization are not known, but it is clear that it ex-

isted.

In Finland the commonly recognized archaeo-

logical periods are as follows: the Viking period cov-

ers the years from

A.D. 750 to 1050, followed by the

Crusade period from

A.D. 1050 to 1150 in western

Finland and from 1050 to as late as

A.D. 1300 in Ka-

relia. Although Finns were not Vikings in the same

sense that the Scandinavians were, they did partici-

548

ANCIENT EUROPE

pate in the eastern trade of furs, silver, and slaves

that was a large part of the Viking activity in these

regions. The fur trade was already becoming impor-

tant in Finland in the fifth century and is credited

with the growth of settlement and apparent person-

al wealth in Ostrobothnia and southern Häme.

Finnish cultural and trade connections extended

from Sweden to northern Norway in the west and

to central northern Russia and the eastern Baltic

lands to the east. Finnish settlements and cemeteries

have been found on the shores of Lake Ladoga in

present-day Russian Karelia. Items of jewelry from

the Perm region of central Russia have been found

in Finnish graves.

Coin hoards from the Viking period, which

occur in large numbers in Scandinavia and else-

where, are much less common in Finland. Not sur-

prisingly, a disproportionate number (nearly a quar-

ter of the total) occur on the Swedish-settled

A

˚

lands. These are mostly ninth- and tenth-century

hoards of Islamic dirhams, a silver coin minted in

vast quantities. The mainland hoards are more re-

cent, from the eleventh century, and contain more

western coins. This pattern matches the general pat-

tern for hoards in other northern countries and re-

flects changing trade relations and silver sources in

Russia and the Islamic countries. The Finns did not

use the coins as money but rather as either raw silver

measured by weight or as ornament. A number of

coins have been found in graves as pendants on

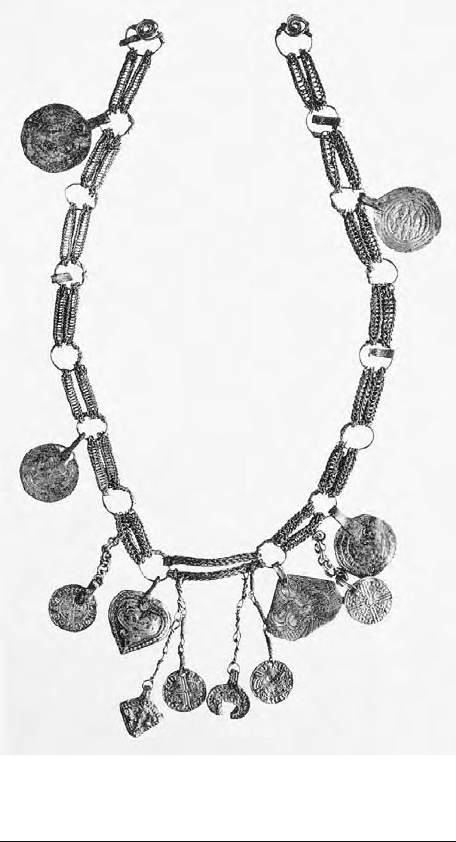

women’s necklaces (fig. 1).

Karelia’s first brush with Christianity came from

the eastern Orthodox Church of Russia, but the

Russians were not intent upon converting the hea-

thens. The Roman Church, on the other hand,

reaching Finland via Sweden, was very interested in

promoting conversion. Many scholars think that

much of Sweden’s interest in this endeavor had to

do with acquiring control over Finnish territory

with the intent to control trade in the eastern Baltic.

By converting the Finns to Christianity, the Swedes

could make Finland dependent on Swedish ecclesi-

astical authority. Some western parts of Finland are

believed to have become Christian, at least officially,

by the year

A.D. 1050, at the end of the Viking peri-

od. This date is probably rather early, except for a

small portion of the population. Over the next cen-

tury, however, Christian influence—as seen from

the evidence of changing burial rites—clearly in-

creased.

Central and eastern Finland became Christian,

under the Roman Church, at progressively later

dates. Swedish domination did not touch Karelia

until c.

A.D. 1300 The interim period in these re-

gions is often referred to as the Crusade period, re-

ferring, specifically, to the crusades in Finland led by

the Swedes. In Karelia, however, Orthodox influ-

ences had some impact when Russian Novgorod,

realizing late in the thirteenth century that it was in

danger of losing its access to the Baltic Sea because

of Swedish encroachments, did finally press for con-

version to Orthodoxy in order to gain stronger Ka-

relian support. The Orthodox form of Christianity

is still espoused by many Karelians.

HISTORICAL SOURCES

Late Iron Age people in Finland had far-reaching

contacts and lived much like their Scandinavian

neighbors. The major difference is that continental

Europe rarely recorded much information about

Finland, and since Finnish society did not develop

its own written language until the sixteenth century,

no contemporary native sources of value exist.

There are a few tantalizing mentions of Finns in

Norse sagas, recorded mostly in the thirteenth cen-

tury, but because Norse terminology often con-

fused the identity of the various cultural groups to

the east, the term “Finn” in Norse texts might refer

mistakenly to the Saami. At first, medieval Finnish

documents were written in Latin or Swedish, for the

literate members of the society were often Swedes

who were not part of Finnish culture. By the six-

teenth century, Finns and others began to write

about their ancient culture, but not until the nine-

teenth century—when folklorists and ethno-

graphers started traveling to the Finnish interior,

particularly to Karelia—did many Finnish stories,

myths, poems, songs, memories, and other cultural

treasures become written texts at last. A central core

collection of these poems was first published as the

national epic for Finland in the mid-nineteenth cen-

tury under the title it continues to bear today, the

Kalevala.

Another group that is occasionally mentioned

in saga texts are the Kainulaiset (“Kvenir,” in Norse

sources). These people are believed to have been

certain Finns from the south who (like the northern

FINLAND

ANCIENT EUROPE

549

Fig. 1. Pendants made from silver coins, Finland, eleventh

century. NATIONAL BOARD OF ANTIQUITIES FINLAND/E. LAAKSO 1950.

REPRODUCED BY PERMISSION.

Scandinavians) organized into large hunting and

trading corporations in order to exploit the more

northerly populations’ ability to hunt animals pro-

ducing valuable pelts. The people of Häme, in par-

ticular, competed with the Norse in what was re-

ferred to in the sagas as the taxation of the “Lapps,”

now known as the Saami. Finnish traders probably

transported many valuable goods from the far north

to Lake Ladoga where they met up with Scandina-

vian and Slavic traders. Another route led from the

Ostrobothnian coast to Karelia via the many inland

rivers and waterways. Traveling through the interior

of Finland in this way was especially useful since dif-

ficult seas, lack of harbors, and the presence of pi-

rates in the eastern Baltic made the movement of

trade goods there a high-risk proposition.

ARCHAEOLOGICAL EVIDENCE

The archaeological remains of Finnish culture from

the Late Iron Age primarily consist of burials and a

growing list of settlement sites, most notably in the

A

˚

land Islands off the southwest coast, which have

a more temperate climate than the rest of Finland

(marked by a greater percentage of deciduous

trees). Island society also prospered from the rich

marine environment and an accessible yet protected

position between Finland and Sweden. Although

ships could carefully navigate the shallow approach-

es to the A

˚

land harbors, no enemy could stage a

swift attack without running aground. Most of the

excavated settlement units on the islands are farm-

steads resembling contemporary sites in Sweden. A

sign of far-flung trade contacts is seen in the “clay

paw”–shaped artifacts found in many graves. These

have their closest parallel in the Volga area of central

Russia. About half of the excavated Iron Age graves

belong to the ninth and tenth centuries.

In Varsinais Suomi, similar geological and envi-

ronmental conditions enabled farmers there to

adopt the more intensive methods of plowed field

cultivation than seen elsewhere in Finland. It was

also possible to keep larger herds of cattle. With

greater food production came the possibility of

denser settlements and towns. The city of Turku

(A

˚

bo in Swedish) in this province was incorporated

sometime between 1290 and 1313. Finland’s first

university arose there. Other early medieval towns

were Porvoo, founded in 1347, and Pori, in 1348.

Most towns were not founded until the fifteenth

century or later. Urbanization came late to Finland.

In southern Häme, near modern Hämeenlinna,

a large but historically undocumented occupation

site, today called Varikkoniemi, has been excavated.

Some believe that the structures found here are the

physical remains of a trading station holding a sig-

nificant level of control over the east-west trade

route through Finland’s interior. The site may date

as early as the Viking period.

The southern Savo region was settled by farm-

ers mostly in the Late Iron Age. A regional survey

project conducted in the 1980s noted seven previ-

ously registered hillforts and approximately twenty

new sites categorized as “ancient guarding posts.”

There are ninety-four so-called cup-marked stones

concentrated in eastern Savo. Many more occur

elsewhere in Finland. The cup-marked stones are

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

550

ANCIENT EUROPE