Bogucki P., Crabtree P. Ancient Europe 8000 B.C.-A.D. 1000: Encyclopedia of the Barbarian World. Volume 2

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

forcing his geopolitical position. To balance the ex-

pansive strategy of the German church, he asked his

closest neighbor, the Bohemian prince Boleslav I, to

send a Christianizing mission together with his

daughter, Dobrava. The first bishop, Jordan, was

responsible directly to the pope, which made the

Polish church independent of German supervision.

The interdynastic marriage of Mieszko and Dobrava

in 965 obliged both courts to maintain political sol-

idarity, which was reflected in their support for the

anti-Ottonian opposition.

This alliance lasted as long as Dobrava lived.

Mieszko took political advantage of her death in

977 to break the Polish-Bohemian partnership. In

979 he married Oda, daughter of the Saxon mar-

grave Dietrich, and became a close ally of the Ot-

tonian empire. His strategic goal was to challenge

Bohemian domination in central Europe. Sometime

in the ninth decade he invaded Silesia and Little Po-

land and included them as southern provinces of his

state, despite diplomatic actions taken by the prince

of Prague, Boleslav II, the son of the Bohemian

prince Boleslav I and Mieszko’s own former broth-

er-in-law.

The Piasts’ strategy of geopolitical isolation of

Bohemia is well reflected in the sequence of quick

marriages arranged for Mieszko’s oldest son, also

named Boleslav. In 984 this Boleslav married the

daughter of the Meissen margrave Rikdag. The

death of this mighty Saxon aristocrat made possible

the annulment of that marriage, which opened the

way to finding a new wife for the young prince in

986/87. This time it was a Hungarian princess,

who was herself replaced in 988/89 by Emnilda,

the daughter of a western Slavonic prince, Do-

bromir. This clever policy restricted potential part-

ners of Bohemia to pagan Polabians and resulted in

Bohemia’s loss of its former dominant position.

After Mieszko’s death in 992, his son, now

Boleslav I, continued the strategy of further ex-

panding and reinforcing his inherited state. Active

in all directions, he ran a complex game of military

and diplomatic actions. His sister was married first

to the Swedish king Eric the Victorious and later to

the Danish king Svein Forkbeard. His daughter was

sent to Rus as the wife of the prince of Kiev, and his

son, Mieszko II, married the German princess Ri-

chesa, the niece of the emperor Otto III.

Boleslav’s real masterpiece, however, was a

summit with emperor Otto III, who came to Gniez-

no in

A.D. 1000. The official reason for this unprece-

dented visit was a pilgrimage to the grave of St. Ad-

albert of Prague (originally called Vojtech), who

had been killed in 997 during a mission to the pagan

Prussians. The emperor substantially reinforced

Boleslav I, however, because he brought with him

Archbishop Radim (Gaudentius), the half-brother

of St. Adalbert, and established an independent

church province with a metropolitan seat in Gniez-

no. Four new bishoprics (in Poznan´, Kołobrzeg,

Wrocław, and Kraków) formed an administrative

network that covered all the lands between the Bal-

tic Sea and the mountain belt. The Polish prince

also was freed from the obligation of paying yearly

tributes and was elevated to the position of a

“brother of the empire,” effectively a monarch

equal to any other in Europe. Since that time the

political name Polonia has been used for the state

that has survived to the present.

A review of the origins of the other early states

(Bohemia, Hungary, Rus) that constituted eastern

central Europe during the tenth century shows a

common strategy applied by their leaders, who all

achieved stable territorial power. None of them had

an overview of the geopolitical situation, and none

could foresee the long-range results of their actions.

Their ability to organize broad support, their deter-

mination in applying coercion, their capacity to

muster the necessary means to sustain power, their

intelligence in borrowing solutions from more de-

veloped neighbors, and simple good luck led to

their supreme successes as first monarchs and cre-

ators of their states.

One may conclude that Poland emerged in the

tenth century as a “private” venture of the Piasts,

who managed to defeat local challengers, stop ex-

pansion of their neighbors, impose Christian ideol-

ogy that legitimized monopolistic rules, organize

effective exploitation of subjugated territory, and

achieve geopolitical acceptance. That state was not

an “emanation” of the political striving of a nation.

It was just the opposite—the Polish nation was a

much later “product” of a state that imposed cultur-

al unification.

See also Iron Age Poland (vol. 2, part 6); Slavs and the

Early Slav Culture (vol. 2, part 7); Russia/Ukraine

POLAND

ANCIENT EUROPE

561

(vol. 2, part 7); Hungary (vol. 2, part 7); Czech

Lands/Slovakia (vol. 2, part 7).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Barford, Paul M. The Early Slavs: Culture and Society in

Early Medieval Eastern Europe. London: British Muse-

um Press; Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2001.

Fried, Johannes. Otto III und Boleslaw Chrobry: Das Wid-

mungsbild des Aachener Evangeliars, der Akt von

Gnesen und das frühe polnische und ungarishe König-

tum. Ein Bildanalyse und ihre historischen Folgen. Stutt-

gart, Germany: Franz Steiner Verlag, 1989.

Görich, Knut. Otto III: Romanus, Saxonicus et Italicus.

Keiserliche Rompolitik und sächsische Historiographie.

Sigmaringen, Germany: Thorbecke, 1993.

Kara, Michał. “Anfänge der Bildung des Piastenstaatens im

Lichte neuer archäologischen Ermittlungen.” Ques-

tiones medii aevi novae 5 (2000): 57–85.

Kurnatowska, Zofia. Pocza˛tki Polski [Beginnings of Poland].

Poznan´, Poland: Poznan´skie Towarzystwo Przyjaciół

Nauk, 2002.

Labuda, Gerard. Mieszko I. Wrocław, Poland: Ossolineum,

2002.

Mis´kiewicz, M., ed. Słowianie w Europie wczes´niejszego

s´redniowiecza [Slavs in early medieval Europe]. Warsaw,

Poland: Pan´stwowe Muzeum Archeologiczne, 1998.

Samsonowicz, Henryk, ed. Ziemie polskie w X wieku i ich

znaczenie w kształtowaniu sie˛ nowej mapy Europy [Pol-

ish lands in the tenth century and their role in the shap-

ing of the new map of Europe]. Kraków, Poland: Un-

iversitas, 2000.

Strzelczyk, Jerzy. Mieszko I. Poznan´, Poland: Wydawnictwo

Wojewódzkiej Biblioteki Publicznej, 1999.

Urban´czyk, Przemysław. Rok 1000: Milenijna podróz˙ trans-

kontynentalna [The year 1000: Millennial transconti-

nental journey]. Warsaw, Poland: DiG, 2001.

———. Władza i polityka we wczesnym s´redniowieczu

[Power and politics in the Early Middle Ages]. Warsaw,

Poland: Funna, 2000.

———, ed. Europe around the Year 1000. Warsaw, Poland:

Institute of Archaeology and Ethnology, 2001.

———, ed. The Neighbours of Poland in the Tenth Century.

Warsaw, Poland: Institute of Archaeology and Ethnolo-

gy, 2000.

———, ed. Origins of Central Europe. Warsaw, Poland: In-

stitute of Archaeology and Ethnology, 1997.

P

RZEMYSŁAW URBAN

´

CZYK

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

562

ANCIENT EUROPE

EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

RUSSIA/UKRAINE

■

FOLLOWED BY FEATURE ESSAY ON:

Staraya Ladoga . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 568

■

The early Russian state emerged between A.D. 750

and 1000, the result of a complex development pro-

cess. Among the most important factors in this pro-

cess were the growth of an economy based on craft

production and long-distance trade and the rise of

urban centers to facilitate the specialized economy

and the administration of the nascent state. These

factors, in turn, were related closely to connections

and interrelationships among peoples living in Rus-

sia, the Baltic Sea area, and the east during the

eighth through tenth centuries.

Primary historical evidence regarding the origin

of the Russian state is scarce, consisting mainly of a

single record, the Russian Primary Chronicle. It is

thought that the chronicle was compiled in the

Monastery of the Caves near Kiev in about

A.D.

1110. According to the chronicle account, in the

early ninth century northern Russia was divided po-

litically into diverse tribal principalities, all of which

owed tribute to the Varangians (Scandinavians). In

859 these principalities rose together against the

Varangians and drove them out of Russia. Without

a central power, the Russian peoples began to fight

among themselves and eventually resolved to invite

the Varangians to return and rule over them. Three

Varangian brothers accepted the invitation. They

moved to northern Russia with their kin and

founded cities from which to rule the area. The old-

est brother was Rurik, who located himself in Nov-

gorod or Staraya Ladoga (depending on the partic-

ular codex consulted). The two younger brothers

also each established a city but died within a few

years, leaving Rurik the sole authority over northern

Russia. In later years Rurik’s successors expanded

and consolidated Russian rule. In 882 Oleg, a de-

scendant of Rurik, established himself in Kiev and

declared that city the capital of Russia, which it re-

mained until the eleventh century.

Although the Russian Primary Chronicle ac-

count has a legendary feel to it, clearly serving to le-

gitimize the rule of the Kievan dynasty over early

Russia, it does provides insight into how the early

state was formed. The document identifies several

key factors in the formation of the early Russian

state: early towns, the diversity of peoples who in-

habited them, and their economic interrelation-

ships. Archaeological research on the formation of

the early Russian state has investigated these key fac-

tors, providing a great deal of information about the

development of early towns as economic and ad-

ministrative centers and about the role of the

Varangians and other early peoples in the area. Most

archaeologists currently believe that the establish-

ment of the early Russian state was a process, not an

event, as the Russian Primary Chronicle presents it.

The process of state formation, as revealed in the ar-

ANCIENT EUROPE

563

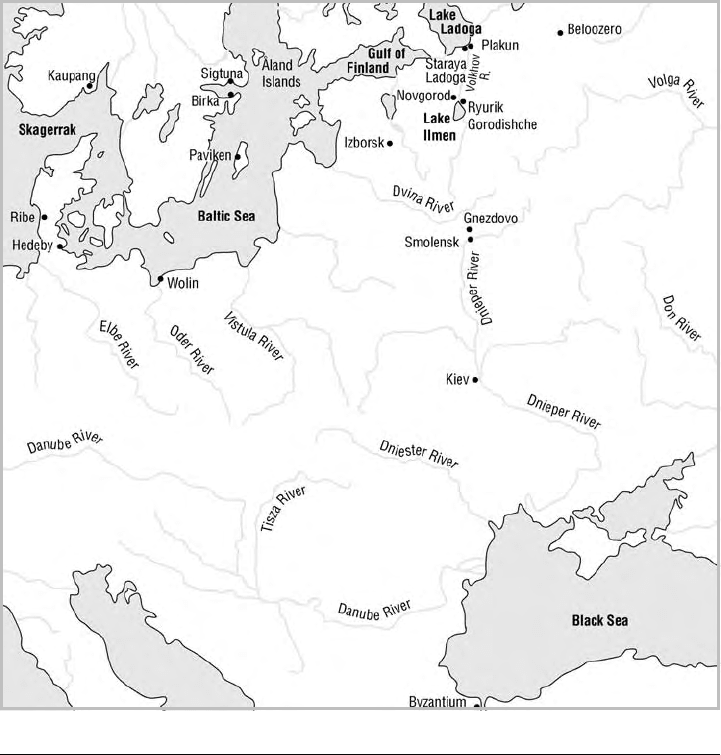

Early medieval towns in Russia, Scandinavia, and Byzantium.

chaeological record, included the growth of a spe-

cialized economy, urbanization, and increasing so-

cial stratification.

State development took place between

A.D. 750

and 1000 in two primary phases. In the first phase,

between about

A.D. 750 and 900, appeared such

early towns as Staraya Ladoga and Rurik Gorodish-

che, whose primary function was to facilitate a long-

distance economy. The focus of these early towns

was on trade and craft production. They had a mul-

tiethnic population, which only in later years was

controlled by a central administration. In the sec-

ond phase, from about

A.D. 900 to 1000, rose such

towns as Novgorod and Kiev, whose primary func-

tion was administration. These later towns showed

evidence of urban planning, the presence of a ruling

elite and a military, and a continuing interest in craft

production and trade.

A.D.

750–900

The peoples who settled in northwest Russia before

the period of state formation belonged to Baltic and

Finno-Ugric ethnic groups. During the eighth cen-

tury, Slavic peoples were expanding north and set-

tling along the southern coast of the Baltic Sea,

while at the same time Scandinavians were moving

south into that area. Organized into small tribal

principalities, these peoples coexisted in northern

Russia. They lived in small villages scattered across

the landscape. Their economy was primarily agrari-

an, with local exchange.

Between

A.D. 750 and 900 the characteristic

settlement pattern and economy of northern Russia

changed rapidly. A number of towns appeared, in-

cluding Staraya Ladoga, Rurik Gorodishche, and

Gnezdovo. These early towns were located at strate-

gic points for facilitating and controlling the grow-

ing trade across the Baltic and through Russia to the

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

564

ANCIENT EUROPE

Far East. The first towns in northern Russia were

different from earlier settlements in two significant

ways: their population was more concentrated, and

they had a specialized economy focused on craft

production rather than agriculture and on long-

distance rather than local trade. They also were no-

table for having a multiethnic population, with indi-

viduals from several cultures living side by side and

engaging in the same economic activities.

Staraya Ladoga.

The earliest known town in

northern Russia is Staraya Ladoga, located south of

Lake Ladoga at the easternmost point of the Baltic

Sea. Staraya Ladoga is important to historians, be-

cause it appears in some versions of the Russian Pri-

mary Chronicle as Rurik’s original seat. To archae-

ologists it is significant because it is the only

northwest Russian medieval town with an unambig-

uous eighth-century cultural layer and with excel-

lent preservation of organic and metallic materials

due to the waterlogged soil. Based on the findings

from Staraya Ladoga, archaeologists have recon-

structed a great deal of information related to the

process of state formation in early Russia, including

the development of a specialized economy, the ap-

pearance of social stratification, and the role of these

factors in the process of urbanization and state for-

mation in Russia.

Staraya Ladoga is situated in an ideal position to

monitor access to the main communication routes

through Russia, the Dnieper and Volga Rivers. In

the mid-eighth century, the earliest settlement at

the town developed along the southern bank of the

Ladozhka, at the point where the tributary entered

the Volkhov River. This location probably was cho-

sen as the best spot for a harbor. The town grew

rapidly. During the mid-ninth century, the north

bank of the Ladozhka was settled, and by the tenth

century the town had expanded to both sides of the

Volkhov.

Early development of Staraya Ladoga was hap-

hazard, but after the mid-ninth century there is evi-

dence for town planning and public works, suggest-

ing that a town administration had evolved. The

center of Staraya Ladoga was fortified in the second

half of the ninth century. In the tenth century, the

town’s streets were laid out on a grid, and a princely

residence was built with provisions for military pro-

tection.

More than one hundred and fifty buildings have

been excavated at Staraya Ladoga. Almost every ex-

cavated building turned up evidence of craft pro-

duction, suggesting that manufacturing was an im-

portant part of the town’s economy and that a

majority of permanent residents were engaged in

craft production. Other activities include agricul-

ture, stock raising, and hunting and gathering, but

these appear minor compared with craft production

and trade. Staraya Ladoga’s economy was organized

around two main spheres: a local and regional ex-

change area and a long-distance exchange area. The

local and regional economy centered on manufac-

turing and trading utilitarian objects and importing

prestige goods and raw materials for the elite. The

long-distance economy involved exporting furs and

other materials, importing foreign prestige goods,

and transferring foreign goods to other trading cen-

ters in Scandinavia, Russia, and the Near East.

There is no clear evidence to suggest that any

particular ethnic group founded or administered the

town, or participated significantly more than any

other in its core activities of trade and manufacture.

In the earliest layers of Staraya Ladoga there are Bal-

tic, Finno-Ugric, Scandinavian, and Slavic materials,

integrated throughout the settlement. Over time

the material culture began to appear more homoge-

nized, suggesting that the town’s diverse ethnic

groups were assimilating a new, local identity. Ar-

chaeological work carried out throughout the Lake

Ladoga region indicates that ethnic integration ex-

isted outside the town as well.

There is also evidence of status differentiation

among the people of Staraya Ladoga. The town

must have had an emerging elite, whose position

was communicated clearly and reinforced by their

consumption of luxury goods and construction of

showy burial mounds. The ordinary folk used utili-

tarian objects and buried their dead in more humble

cremation graves. The elite probably did not orga-

nize or control the economy of the town early in its

history, but their influence and authority over the

town and its activities increased through time.

Staraya Ladoga is best understood as a trade and

manufacturing town, one link in the network that

connected Scandinavia, the eastern Baltic, and the

Far East. From its earliest days, the town had far-

reaching trade contacts and an economy based

RUSSIA/UKRAINE

ANCIENT EUROPE

565

largely on commerce and the production of trade

goods.

Staraya Ladoga developed around the same

time that new peoples were moving into northern

Russia, notably Scandinavians and Slavs. These

newcomers, together with the existing population

of Balts and Finns, played an important role in sti-

mulating trade and the growth of towns and thus

ultimately encouraging craft specialization and in-

creasing class stratification. The participation of nu-

merous ethnic groups in the same range of econom-

ic activities seems to have contributed to the

development of a new local identity and the mini-

mizing of previous ethnic differences.

Rurik Gorodishche.

Rurik Gorodishche is located

on an island north of Lake Ilmen, which is midway

down the Volkhov. In the ninth century Rurik Go-

rodishche and Staraya Ladoga were the largest set-

tlements in northwest Russia. While Staraya Ladoga

served as gateway to Russia from the eastern Baltic,

Rurik Gorodishche controlled access to the Russian

river routes. Traders heading to the Bulgar state via

the Volga or to Kiev and Byzantium via the Dnieper

would pass through Lake Ilmen.

Rurik Gorodishche was a trade and craft pro-

duction center in the ninth and tenth centuries, tak-

ing advantage of its location. Craft production

seems to have been important to the town’s econo-

my, given the quantities of production debris and

materials recovered during excavations. Scales and

weights indicate that trade also took place in the

town. Goods from the Mediterranean, the Baltic

Sea, and Scandinavia have been found at the site.

The population of Rurik Gorodishche, as at Staraya

Ladoga, included many ethnic groups: Finns, Balts,

Slavs, and Scandinavians. Evidence from burials,

jewelry, and other sources suggests that these

groups mutually influenced each other and gradual-

ly developed a composite local identity that blended

elements from all of the cultures.

Evidence for fortifications and weapons suggest

that Rurik Gorodishche (“Rurik’s Fortress”) was an

administrative and military center early in its history.

Staraya Ladoga was fortified at about the same time

that Rurik Gorodishche was established as a forti-

fied center, perhaps indicating that fortifications

were a common precaution or a statement of power

in the mid-ninth century.

Archaeological research shows that Staraya

Ladoga and Rurik Gorodishche (as well as other

early towns, such as Beloozero and Gnezdovo/

Smolensk) share many common features in their de-

velopment and character: an economy based on

trade and craft production, a strategic location

along developing trade routes, and a multiethnic

population. Other Baltic trade towns manifest these

same features, including Hedeby and Ribe in Jut-

land, Kaupang in Norway, Paviken on Gotland,

Birka in central Sweden, and Wolin in Poland.

A.D.

900–1000

By A.D. 900, many towns existed in Russia, includ-

ing Staraya Ladoga and Rurik Gorodishche. These

early towns encouraged the development of a novel

specialized economy based on crafts and trade, fos-

tered the interaction of numerous ethnic groups,

and depended upon a limited amount of urban ad-

ministration. Between

A.D. 900 and 1000, a new

kind of town arose in Russia, which was associated

closely with the development of an elite class and a

central government. As ethnic differences became

less pronounced in urban populations, social strati-

fication became more prominent. Tenth-century

towns, such as Novgorod, increasingly served as ad-

ministrative and economic centers for their territo-

ries, encouraging interdependence among the

urban and rural settlements. The rise of Kiev in the

late tenth century unified Russian towns and their

territories under one central administration and fur-

ther increased the social, political, and settlement

hierarchy of early Russia. By

A.D. 1000 Kiev effec-

tively served as capital of the early Russian state.

Novgorod.

Novgorod was established in the mid-

tenth century, two kilometers from Rurik Gorod-

ishche in the Lake Ilmen area of northern Russia. In

many ways, early Novgorod resembled its neighbor-

ing settlement. Novgorod was home to extensive

craft production; about one hundred and fifty work-

shops have been found so far in the archaeological

record. Connections with long-distance trade are

indicated by imported objects from the north,

south, east, and west. The material culture em-

braced elements from Slavic, Scandinavian, Baltic,

and Finno-Ugric groups, which indicates that there

were mutual cultural influences.

Despite the basic similarity between the two

towns—a multiethnic population concerned with

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

566

ANCIENT EUROPE

craft and trade activities—Novgorod had a different

character from that of nearby Rurik Gorodishche.

Archaeologists have recovered copious evidence of

a greater elite presence at Novgorod than at Rurik

Gorodishche. In Lyudin End, where the earliest

traces of settlement have been found in Novgorod,

individual house lots generally fit into one of two

types. The first type, a narrow rectangular lot about

15 by 30 meters, is thought to have belonged to

regular urban residents. The second type of lot, up

to three times as large as the first, has been identified

as residences for elite class. The conspicuous con-

sumption of luxury goods in Novgorod also sug-

gests well-developed social differences among the

town’s population. The evidence for an elite pres-

ence is so striking that some scholars have suggested

that Novgorod may have been founded as an elite

settlement.

In the late tenth or early eleventh century, Nov-

gorod appears to have taken over administrative

functions for the Lake Ilmen area and perhaps for

all of northern Russia. Novgorod probably also was

the religious center of northern Russia, first for the

pagan religion and then for Christianity. By about

A.D. 1000 Rurik Gorodishche and Novgorod may

have had complementary functions, together serv-

ing as the urban center of the Lake Ilmen region.

Contemporary examples of similar paired settle-

ments have been excavated in other areas of the

eastern Baltic, including Hedeby and Schleswig in

Jutland and Birka and Sigtuna in central Sweden. In

these cases, as in Rurik Gorodishche and Novgorod,

the earlier settlement was a craft and trade center

particularly reliant on long-distance trade, flourish-

ing from the eighth through the tenth centuries.

The later settlement, beginning in the late tenth or

early eleventh century, was an administrative and ec-

clesiastical center. In both Russia and Scandinavia

the rise of these urban settlements appears to have

been related to the greater sociopolitical and eco-

nomic changes that played a part in early state devel-

opment.

Kiev.

Kiev is located on a promontory on the west

bank of the Dnieper River, about 10 kilometers

south of the confluence of the Dnieper and the

Desna. From this position Kiev controlled the lower

Dnieper. Archaeological evidence indicates that the

character and extent of settlement on the Kiev

promontory changed dramatically between the be-

ginning of the tenth century

A.D. and the first half

of the eleventh century. The settlement expanded

tenfold, filling the hills of the promontory and

stretching along the riverbanks of the Dnieper. Eco-

nomic specialization increased as craft production,

including bronze casting and iron production,

flourished. Long-distance trade partners included

the Muslim east, the Bulgar state, and the Byzantine

Empire.

The town’s dense population and specialized

economy suggests that Kiev must have been depen-

dent upon tribute or some other means of exacting

agricultural and subsistence products from the sur-

rounding countryside. According to the Russian

Primary Chronicle, Prince Oleg established Kiev as

preeminent over all Russian cities in

A.D. 882 and

gathered tribute from all the Russian lands. A forti-

fied area was established on Starokievska Hill c.

A.D.

900, with large stone structures that may have been

princely residences. By about

A.D. 1000 this fortress

probably served as an administrative center for the

area, effectively unifying the scattered settlements in

the Kiev area into one urban and tributary unit.

Burial and architectural evidence shows that

Kiev was a multiethnic and socially stratified com-

munity. Slavic, Baltic, Finno-Ugric, Scandinavian,

and Byzantine elements are present in the burial

customs and building methods of Kiev during this

period. After Kiev was established as the Russian

capital, the population of Kiev appears to have be-

come more ethnically homogeneous. This no doubt

occurred through natural assimilation of the various

groups living in Kiev as well as through the intro-

duction of Christianity. In 988, the Russian Primary

Chronicle reports, Prince Vladimir of Kiev intro-

duced the Christian church to Russia. Social stratifi-

cation, in contrast to ethnic diversity, increased

through time.

Archaeological and historical sources indicate

that the early Russian state had emerged by

A.D.

1000, with centralized rulership at Kiev exercising

political and economic control over an extensive

area, from the shores of the Gulf of Finland and

Lake Ladoga in the north down to the Black Sea in

the south. Kievan Russia developed diplomatic and

trade relations with its neighbors, including Scandi-

navia, Europe, the Islamic Caliphate, the Bulgar

Khazarate, and the Byzantine Empire. The Russian

state also had converted to Christianity, and the

RUSSIA/UKRAINE

ANCIENT EUROPE

567

lands and peoples under its control were beginning

to evince social and cultural institutions considered

to be characteristically “Russian.”

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

The development of the early Russian state took

place between

A.D. 750 and 1000. Several factors

contributed to the formation of the state: the

growth of early towns as trade and administrative

centers, the elaboration of a specialized economy;

and the development of social stratification. Be-

tween

A.D. 750 and 900 the first towns arose in Rus-

sia, relying on and encouraging the development of

an economy based on craft production and long-

distance trade. Early Russian towns, such as Staraya

Ladoga and Rurik Gorodishche, share many com-

mon features: an economy based on trade and craft

production, a strategic location along developing

trade routes, and a multiethnic population. As such,

they were similar to other trade towns in Scandina-

via and northern Europe. The eighth- and ninth-

century trade towns created a basis for statehood in

these regions, contributing to the expansion of a

specialized economy, social stratification, and cen-

tral administration.

Between

A.D. 900 and 1000, a different kind of

urban center became established in Russia, adminis-

trative and ecclesiastical centers that integrated the

urban and rural economy. In Russia and Scandina-

via the appearance of these administrative centers

settlements resulted from and contributed to the

sociopolitical and economic changes associated with

the formation of a state. Novgorod served as one

such political center, administering taxation and

collecting tribute in northern Russia during the

tenth century. Kiev in central Russia (now Ukraine)

grew alongside Novgorod, eventually surpassing it

and all other Russian cities in economic and political

importance.

See also Rus (vol. 2, part 7); Staraya Ladoga (vol. 2, part

7).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Brisbane, Mark A., ed. The Archaeology of Novgorod, Russia:

Recent Results from the Town and Its Hinterland.

Translated by Katharine Judelson. Lincoln, U.K.: Soci-

ety for Medieval Archaeology, 1992.

Callmer, J. “The Archaeology of Kiev to the End of Its Earli-

est Urban Phase.” Harvard Ukrainian Studies 11, nos.

3, 4 (1987): 323–364.

Clarke, Helen, and Björn Ambrosiani. “Towns in the Sla-

vonic-Baltic Area.” In their Towns in the Viking Age, pp.

107–127. Rev. ed. Leicester, U.K.: Leicester University

Press, 1995.

Graham-Campbell, James, Colleen Batey, Helen Clarke et

al., eds. “Russia and the East.” In their Cultural Atlas

of the Viking World, pp. 184–198. New York: Facts on

File, 1994.

Jansson, Ingmar. “Communications between Scandinavia

and Eastern Europe in the Viking Age: The Archaeo-

logical Evidence.” In Untersuchungen zu Handel und

Verkehr der vor- und frühgeschichtlichen Zeit in Mittel-

und Nordeuropa. Vol. 4, Der Handel der Karolinger-

und Wikingerzeit. Göttingen, Germany: Vandenhoeck

& Ruprecht, 1987. (Includes articles in English.)

Ostman, Rae Ellen M. “Our Land Is Great and Rich, But

There Is No Order in It: Reevaluating the Process of

State Formation in Russia.” Archaeological News 21–22

(1996–1997): 73–91, 150–155.

Rahbeck-Schmidt, K., ed. Varangian Problems. Scando-

slavica Supplement 1. Copenhagen, Denmark: Munks-

gaard, 1970.

Stalsberg, Anne. “Scandinavian Relations with Northern

Russia during the Viking Age: The Archaeological Evi-

dence.” Journal of Baltic Studies 13, no. 3 (1982): 267–

295.

Uino, Pirjo. “On the History of Staraja Ladoga.” Acta Ar-

chaeologica 59 (1988): 205–222.

Vernadsky, George, ed. A Sourcebook for Russian History

from Early Times to 1917. New Haven, Conn.: Yale

University, 1972.

Yanin, V.L. “Medieval Novgorod: Fifty Years’ Experience

Digging Up the Past.” In The Comparative History of

Urban Origins in Non-Roman Europe: Ireland, Wales,

Denmark, Germany, Poland and Russia from the Ninth

to the Thirteenth Century. Edited by H. B. Clarke and

A. Simms. BAR International Series, no. 255. Oxford:

British Archaeological Reports, 1985.

R

AE OSTMAN

■

STARAYA LADOGA

Staraya Ladoga, in northwestern Russia, was one of

the most important trade and craft production cen-

ters of the eastern Baltic during the early Middle

Ages. Located at the eastern end of the Baltic, the

town was a gateway between the Baltic Sea and Rus-

sian river routes to the Black Sea. Staraya Ladoga

also is cited by some versions of Russia’s earliest his-

torical document, the Russian Primary Chronicle, as

the seat of Rurik, Russia’s first ruler.

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

568

ANCIENT EUROPE

SETTLEMENT

Early settlement at Staraya Ladoga has been thor-

oughly and systematically excavated, resulting in a

detailed picture of life in an eastern Baltic trade

town from

A.D. 750 to 1200. A total of 3,600

square meters of medieval Staraya Ladoga have

been excavated, of an estimated settlement area of

15 square kilometers. The waterlogged soil at the

site has resulted in excellent preservation of finds,

and dendrochronology has allowed the finds to be

dated precisely.

As a result of the extensive excavation program,

archaeologists can sketch a clear picture of the de-

velopment and character of early Staraya Ladoga.

The Earthworks Fortress quarter of the town was

settled the earliest, beginning in about

A.D. 760.

This area probably was the most suitable place for

a harbor. Settlement expanded into the Varangian

Street quarter in about

A.D. 842. Once established,

these early settlement areas were occupied continu-

ously throughout the Middle Ages. In the ninth and

tenth centuries, the trade town began to appear

more urban, with more clearly defined areas and

functions. Staraya Ladoga was given wooden fortifi-

cations in the 860s and stone fortifications in 882.

Dwellings and public buildings were concentrated

within the town walls. Sacred places and cemeteries

were located outside the walls. In the tenth century,

a regular street grid was established. At this time the

population of the town was slightly more than one

thousand persons.

More than one hundred and fifty medieval

houses have been excavated at Staraya Ladoga, dat-

ing from the eighth century through the eleventh

century

A.D. The medieval buildings are of two main

kinds, a small and a large type. The small buildings

are approximately 5 meters square and have a corner

hearth. The large buildings measure approximately

13 by 10 meters and have a central hearth. Archae-

ologists have not found an explanation for the coex-

istence of the two building types. At one point

scholars believed the larger buildings might have

predated the smaller buildings, but this hypothesis

has been rejected. Likewise, attempts to identify the

building types with different ethnic groups living in

Staraya Ladoga have been unsuccessful.

One well-preserved building in the Earthworks

Fortress quarter is of exceptional size. Built in 894,

it measured approximately 17 by 10 meters. A

hearth was located in a walled-off interior room

measuring approximately 10.5 by 7.5 meters. More

than two hundred glass beads and thirty pieces of

amber were found associated with the building,

suggesting that its occupants were involved in trade.

Ibn Fadlan, an Arabic scholar, wrote in 921 or 922

that the Rus traders who sailed down the Volga

River built large timber structures that could house

ten to twelve people.

Burial mounds were erected along the Volkhov

River, in locations where they would be visible from

a distance. More than thirty burial mounds are still

extant at Staraya Ladoga. It is thought that one of

the largest mounds at Staraya Ladoga was built for

Oleg (879–912), the ruler who united northern and

southern Russia. The cemetery of Plakun is notable

for the ten or so Scandinavian boat burials. Other

cemeteries at Staraya Ladoga include Baltic, Finno-

Ugric, and Slavic burials.

ECONOMY

From its earliest days, Staraya Ladoga’s economy

was based on trade and the production of trade

goods. The town was an important node in the

routes between the Baltic Sea and the river routes

across Russia to the Far East. Staraya Ladoga con-

trolled a substantial part of the route, from the Bal-

tic to the lower reaches of the Volkhov River. From

the lower Volkhov, traders would take either the

Volga route to the Caspian Sea and the Islamic Ca-

liphate or the Dnieper route to the Black Sea and

the Byzantine Empire.

Silver and trade scales indicate that merchants

exchanged goods in Staraya Ladoga. In addition to

local trade goods, including crafts, timber, honey,

and slaves, goods from other areas also traveled

through Staraya Ladoga: furs from Viking Scandi-

navia, combs from Frisia, beads from the Mediterra-

nean, swords from the Frankish kingdom, and

amber from the Baltic. Traders exchanged these

goods in the Far East for silver coins, carnelian and

rock crystal beads, silk, and warrior-style clothing,

ornaments, and accessories.

Local craft production at Staraya Ladoga is indi-

cated by finds of raw materials, tools, various prod-

ucts found at different stages of completion, reject-

ed (flawed) products, and manufacturing debris.

Almost every house excavated in the town turned

up evidence of such craft production. Glass beads

STARAYA LADOGA

ANCIENT EUROPE

569

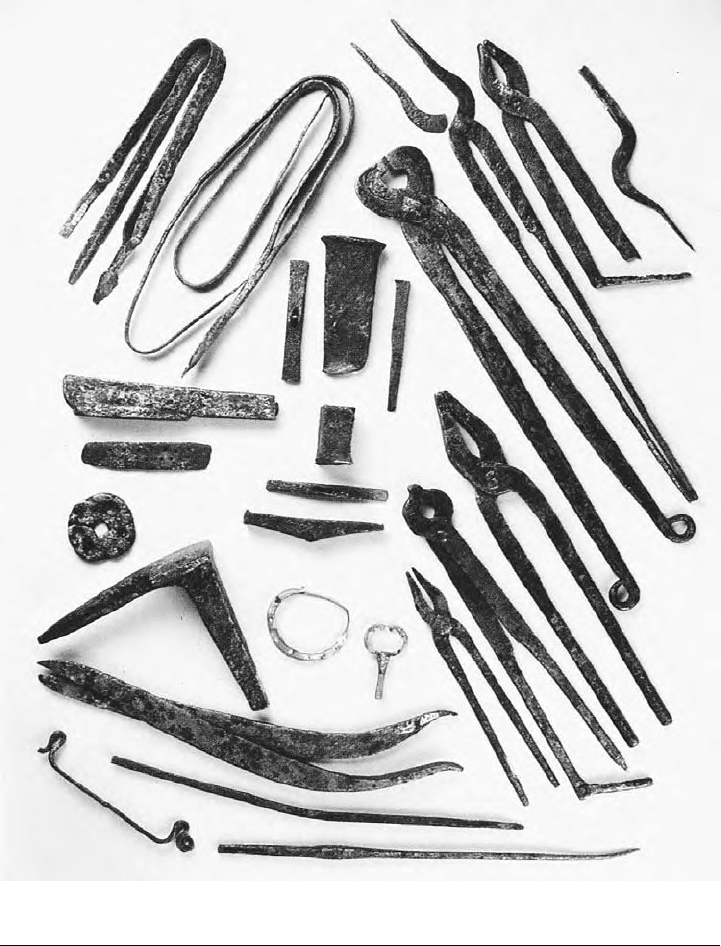

Fig. 1. Hoard of metalsmith’s tools from Staraya Ladoga. THE STATE HERMITAGE MUSEUM, ST.

PETERSBURG. REPRODUCED BY PERMISSION.

may have been crafted in the glassworks found at

Staraya Ladoga. A smithy dating to the 760s was

equipped for bronze casting, with a smelting

hearth, casting molds, and a collection of twenty-six

metalworking tools (fig. 1). Amber was imported

from the Baltic and worked at the site. Pottery was

manufactured locally, first using hand-built con-

struction and later the fast wheel. Bone and antler

were fashioned into numerous objects, including

knives and combs. Wooden objects were turned on

lathes and carved manually. Textile tools (spindles,

whorls, and flax-processing tools) were used to

create the finished cloth found in the town. Leather

footwear also was produced in early medieval

Staraya Ladoga.

Agriculture, stock raising, gathering, and hunt-

ing also occupied the early occupants of the town

and its countryside. Agricultural tools, including

plowshares, are preserved in the archaeological

record. Botanical remains comprise cultivated cere-

als, such as millet, and locally gathered plants and

berries. Animals were raised in cattle pens and

sheds. Domesticates included cows, pigs, sheep,

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

570

ANCIENT EUROPE